9 minute read

Life With Lupus: A Chronic Illness Story

Society often hears “illness” and is inclined to contest it with treatments and cures. When you’re sick, you might feel inclined to get a prescription for an antibiotic or other drug. On the flip side, so-called health gurus claim that acupuncture, herbalism, and juice cleanses will cure everything. But what if there is no cure, and the goal is simply survival? That is, how do you live the best life you can with a chronic illness?

I have systemic lupus erythematosus, otherwise known as SLE or lupus. I also have lupus nephritis and chronic kidney disease as a result. Lupus is an autoimmune disease, which means that the immune system mistakes healthy tissues for foreign invaders and attacks them. Lupus causes pain and inflammation in many parts of the body, which can produce a variety of different symptoms.

Advertisement

At the time I began to have symptoms, I was fourteen years old. I was active in sports, got plenty of sleep, and ate relatively healthily. People often invalidated my symptoms and said that they were “in my head” or a result of something I did. Swollen joints? Too much texting. Fatigued? You’re going to bed too late. Visits to urgent care and the ER were dismissive, providing no answers to my persistent fevers or why my bug bites wouldn’t heal. Eventually, my parents and I could no longer ignore my hair loss, rashes, and mouth sores. The swelling and joint pain worsened to the point that I was unable to walk up the stairs or clasp my hand around a toothbrush. My independence went out the door. Perfect attendance at school turned into missing a straight month of class. I lost weight rapidly, and my whole body was weak and in pain. Sadness, defeat, and fear swelled in my heart. My body was transformed as the illness took on its own reality, one whose rules were mysterious and hostile.

For many, the journey towards a diagnosis of a chronic illness includes being misdiagnosed, tested, and retested. Sometimes, it involves being misunderstood and discredited by those around you, even loved ones and medical professionals. For me, numerous tests and visits to specialists led to admission to C.S. Mott’s Children’s Hospital. There, I was officially diagnosed with lupus. It was a huge relief to receive answers and treatment, but I was also terrified. I didn’t want to be “sick.” I liked helping others, but I never imagined I would be the one needing help.

At the onset of my diagnosis, I had the worst flareup in my life. Kneeling on the cold tile floor of a hospital bathroom, I clutched my IV and prayed to die. I felt like I couldn’t do it anymore, physically, mentally, or emotionally. MRIs, ultrasounds, a kidney biopsy, and other tests later revealed that there was inflammation in several major organs, which was causing severe pain. This was the only day I wholeheartedly wished to be dead, and I still tear up thinking about it. Life throws us curveballs, and sometimes, survival is taking it one day at a time. We ride out the bad moments to appreciate the good ones.

In the grand scheme of things, my journey towards diagnosis—six months, if that—was shorter and less infuriating than that of many others, and for that, I am grateful. But enough damage was done to my kidneys that I needed aggressive treatment. Besides being pumped full of corticosteroids, that initial week in the hospital marked the first chemo infusion I needed to calm down my immune system. At the time this was happening, I received an influx of sympathy and accommodations. I was repeatedly told how strong I was by my classmates and peers, which I appreciated during my battle with lupus and the side effects of its treatments. Side note: No matter how stupidly dedicated you are to your education, do NOT try to attend class the day after a chemo infusion.

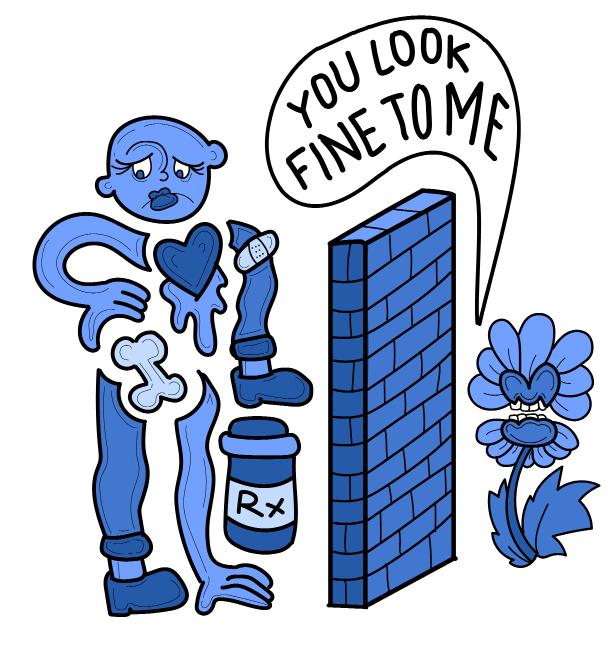

But no one warned me about the aftermath. Once the rashes, head coverings, and other external signs of illness disappeared, my pain and illness became nearly invisible. Even though no one could see it, I still suffered from symptoms such as joint pain and fatigue. The real strength comes into play while surviving day-to-day life, as incurable suffering makes other people uncomfortable. “You’re all better now, right?” “Why are you cancelling plans?” “You’re young, you’re fine.” “You don’t look sick to me.” Although sometimes well meaning, these responses negate the reality and seriousness of chronic illness. Something

isn’t imaginary just because it is invisible, and pretending it is could lead to a potentially lifethreatening situation.

College can be a stressful time, and a chronic illness can complicate life. I’m extremely grateful that I live my day-to-day life like a “normal” healthy person with relatively few lupus flareups. However, some symptoms are persistent, and I have to actively watch for triggers or signs of an oncoming flare-up. Additionally, treatment has its own side effects and can be complicated because of immune-suppressing medications. Since a suppressed immune system is an inevitable part of treatment for my illness, it often takes a long time to recover from infections. For example, a sinus infection my freshman year took three months to recover from (courtesy of dorm life), and a different infection my sophomore year resulted in an ER trip the night before a midterm.

When I walk through campus with aching joints and brain fog, I find myself engaging in a negotiation process with the world around me. I try my best to put on a brave face, concealing any pain along with feelings of shame. It’s strange to be young but not feel as immune as my peers. I’m always the designated “sober friend,” since I can’t drink with my meds and condition. Sunscreen is a necessity (no tanning allowed), as is plenty of sleep. I have accommodations to use a computer for note-taking and sometimes feel awkward doing so due to the social stigma surrounding disability, accommodations, and illness.

This pandemic has challenged my perspective of illness, too. When someone dies of COVID-19, the first question that pops up is whether or not the person had an underlying health condition. While understandable, I am often at odds with people in my age group when the topic comes up. Sometimes it feels like people with “underlying health conditions” are viewed as expendable. The other day, I had a conversation with someone about this very subject: “I get that COVID-19 can be serious, but why should I have to stop living my life? We can’t live in fear, and it’s not my fault that other people have health conditions.”

And they are right, it’s not their fault; however, it’s not exactly as though I did anything wrong to have lupus. In a situation such as a pandemic, it’s true that people need to face harsh realities rather

than hide behind platitudes. Addressing the facts takes some of the fearful arbitration away, as it can be comforting to know that there are determining factors beyond luck. It also makes sense that the people who are most at risk should act accordingly.

What concerns me is the human inclination to create separation between “us” versus “them,” as the line between “sick” versus “not sick” is not always clear- cut. The vulnerable are not some separate group to the rest of society. Anyone—neighbors,

classmates, relatives—may have ongoing health conditions that you do not know about. A preexisting health condition isn’t always obvious, nor does having a chronic illness mean that a person has poor health overall. Many chronic illnesses aren’t outwardly visible, so those who don’t suffer from them often misunderstand them.

We tend to believe that we have the power to prevent disasters in our lives, and a chronic illness throws a wrench into that process. Getting sick and staying sick is not some sort of moral failing as if due to lack of will or hard work, though the attitudes towards it can make it seem that way. Sometimes I even catch myself thinking, “I’m a burden to myself and those around me. Why can’t my body just cooperate?” I’m ashamed to be giving in to pain and fatigue and to have ever taken good health or youthful vigor for granted.

I’ve learned to embrace my autonomy while honoring my limitations. High stress levels or a lack of sleep can easily lead to flare-ups or exacerbate a condition, so it’s important to balance my schedule and plan ahead. Occasionally, the fatigue or flare-up pain can make it difficult to get out of bed, for which the current virtual format has been convenient. On days that my body does not want to cooperate, I have to listen and say no, not today to some of the more strenuous demands of my time. As a people-pleaser who likes to keep busy, this can be hard to admit sometimes, but balancing a routine of school and work with self-care is one of the best things I’ve done for my productivity and wellness.

I try to be optimistic, though a positive outlook alone can never heal me. As contradictory as it might sound, experiencing a chronic illness has increased my zest for life. Knowing what it is like to go without something can increase appreciation for it, from strenuous activities like running to basic functions like fastening buttons. I can’t speak on behalf of everyone with a chronic illness, but the experience can be incredibly humbling. Managing our bodies, diagnoses, and negotiating with the world around us is as much of an ongoing process as our illnesses. To survive is to persevere, but it is also to take care of ourselves. You know that feeling when you have a stuffy nose from the common cold or allergies, and you swear you won’t take breathing for granted again? With a chronic illness, I’ve learned to be grateful and to appreciate all the good things I have, including times of good health. I hate my body. I love my body. I hate that it causes me pain, but at the same time, I know that it fights for me every single day.

Talking about this topic is nerve-wracking, but I feel as though it is important to hear, especially to those who are looking to understand chronic illnesses or have one themselves. If you know someone with a chronic illness who is

going through a difficult time, please try your best to not judge them. Be patient with them. And to anyone struggling with a chronic condition, you are not alone. Remember that it is okay to take a break and focus on your needs. Listen to your body and fight for it. It’s important to be your own health advocate, but also know that there are people and organizations you can reach out to. Talk to your professors ahead of time. Acquaint yourself with the medical services available to you. Also, don’t be afraid to reach out to find support services and accommodations. College life and its new experiences can be a lot to handle, and a chronic illness certainly doesn’t make it any easier, but I’ve learned that by prioritizing my needs and preparing ahead of time, I can overcome any challenge I may face.