7 minute read

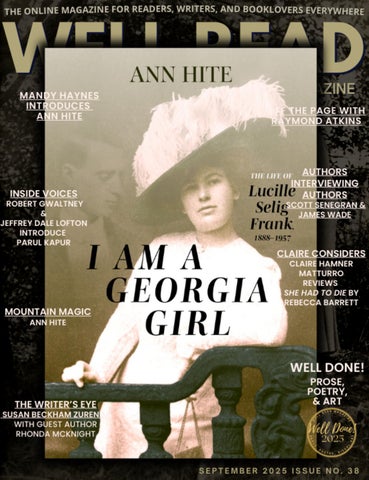

MOUNTAIN MAGIC with ANN HITE The Georgia Girl

As of this writing, my first real nonfiction book—I don’t count the memoir because that is my story—will be released into the world in two weeks. The experience is much the same as when my first book was published. Writing nonfiction about a famous historical event is intimidating to say the least, but the story of Lucille Selig Frank is close to my heart. My attachment to this story is somewhat unusual.

On August 5, 1915, my granny lost her mother, Asalee Redd Hawkins, to a head injury inflicted by granny’s father, Henry Lee Hawkins, when he pushed Asalee out of their Model-T going down the road. Granny was six years old. Twelve days later she watched Leo M. Frank, superintendent of the National Pencil Company in Atlanta some forty-five miles away, ride by in the back of a Model-T car, one of six. What she witnessed was the vigilantes who kidnapped Leo from the state prison in Milledegville, Georgia taking him to Marietta where they planned and did lynch him. The day was August 17, 1915, 110 years ago. Henry Lee gathered Granny and her siblings for a trip to Marietta.

Granny did not witness the actual lynching. The only people present for this killing was the vigilantes and a Blue Ridge Circuit Judge, Newt Morris, who was well know in Granny’s hometown of Cumming, in Forsyth County. Judge Newt Morris presided over the trial of Ernest Knox and Oscar Daniell—two African-American teenagers found guilty of murdering Mae Crow in 1912. Judge Morris sentenced them to hang on very little evidence. This trial was closely followed by Atlanta newspapers just as Leo M. Frank’s murder trial was covered in 1913.

Leo M. Frank was found guilty of Mary Phagan’s brutal murder in the National Pencil factory on April 26, 1913. Leo was the last person to see Mary alive that day when she picked up her pay. Leo was sentenced to death by a jury of twelve white men, but Governor John Slaton commuted this death sentence to life in the state prison because he was convinced the evidence didn’t show he was the killer. This enraged many who believed Leo was guilty and a plan was hatched by several lawmakers from Cobb County, Georgia to make sure Leo got what they believed was justice.

By the time Granny arrived on the scene, the lynching party was long gone. In their place was the good citizens who came out to Marietta to celebrate the lynching of Leo Frank by seeing his body hanging from a tree. Granny was one of the many children brought out to view his body. A thousand people came to the piece of property owned by former Cobb County sheriff William Frey, who was believed to be the man who tied the hangman’s noose.

When I was nine years old, Granny told me the story of the day she saw Leo hanging from the tree with blood running down his nightshirt from his reopened throat wound. She went into detail about how this lynching took place and at the end of the story, she told me that Leo’s last known words was for his wedding ring to be returned to Lucille, his beloved wife. This was the part of the story that stuck with me more than anything else. I imagined Lucille receiving the wedding ring of her husband. A ring she wore for the rest of her life.

I have always said my granny was partly responsible for me becoming a writer even though she didn’t live long enough to know I became a published author. It was her stories laced with mountain magic that tangled inside of me urging me to tell them. The story of Lucille was no different. At first, I thought I would write Lucille as a historical fictional character. While researching in 2013, I realized that no one had written a nonfiction account of Lucille Selig Frank. She so deserved her story to be told. That’s when I decided to write a nonfiction narrative of Lucille and acknowledge the voices of the other women tied in with this horrific story. Women were marginalized in this time of history. Ladies didn’t speak out and say what they thought, but Lucille did. Yet, the newspapers portrayed her as hysterical and weak like most women were represented. The more I researched, the more I found about the strong women in Lucille’s family. Then I considered the women on Mary Phagan’s side. These women had strength we rarely find now. Yet, often in the newspapers, their remarks, especially Fannie Coleman’s—Mary’s mother—were found on page six or seven of the newspapers.

And now as I look at the finished book, bound with Lucille in all her finery and Leo as a ghostly image in the background, I wonder if Granny knew what I would do? Was it her intention for me to stew about this story and others she passed to me until I turned them into books?

Granny was a hardy reader and understood the power of the written word. And maybe that was her magic, dear readers. Maybe she taught her granddaughter through storytelling how history repeats itself, and we each have a responsibility to try to keep this from happening.

Now, maybe my readers believe the mountain magic in this piece is Granny telling her stories and dear readers, you would be right, but there is more. When the book was finished and in the hands of my publisher, a man named Mike Weinroth found me through a bookseller, which I can assure you was not an easy task. Mike knew Lucille’s great nephew and wanted the two of us to meet.

Can you see the hand of mountain magic?

I met with Chuck Marcus in early 2025. He told me stories about Lucille because he could remember her quite well since he was thirteen when she died in 1957. He showed me what Lucille was like when she grew older. What a gift. But that’s not the only gift he passed to me. The day I met with Chuck, I was shown what could be—it has not been proven—a gold wedding band he inherited from Lucille. The proof that this ring belonged to Leo is still being researched, but something deep inside me whispered it was the real deal. Holding this ring was life changing as a writer. Ah, but that is not all dear readers.

That afternoon, I left with Lucille’s writing desk. Can you imagine what a gift this was? Each day since I received it, I sit at her desk and write. This was a mountain magic moment, my readers.

Lucille became a quiet, private woman after Leo was lynched. I worried from the beginning of this project I might be invading her privacy, and she wouldn’t have liked that. When that desk became mine, I felt her smiling as if she were saying, good job, good job. Lucille became more to me than a character in history. I lived with her stories for ten years of researching and writing. I dare anyone to read this story and not understand how important it is to the world we live in today. It’s relevant to what we watch on the news and read in the papers.

Lucille spoke one more time to the press in the fall of 1915 about Leo’s lynching. One of the things she said was “I am a Georgia girl…” This quote became the title of the book. My heart will always be in this story, and I’m sure I haven’t written the last word on the subject.

Embrace the mountain magic. It’s really there at work.