8 minute read

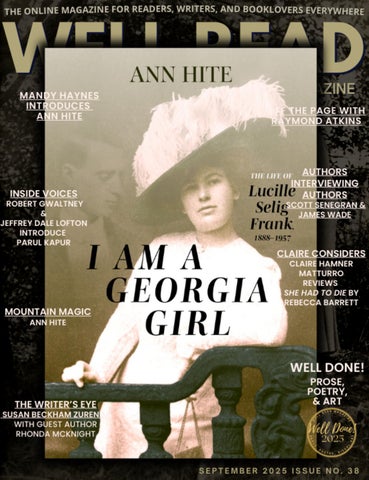

MANDY INTRODUCES SEPTEMBER’S FEATURED AUTHOR, ANN HITE

It’s my honor to introduce September’s featured author, Ann Hite. She is one of our co-editors here at WELL READ with her monthly column, Mountain Magic, and I’m so proud to have her on the team. She is the author of the award-winning Black Mountain series. Ghost On Black Mountain, her debut novel, was one of ten finalist for The Townsend Prize in 2012 and won Georgia Author of the Year in 2012. Lowcountry Spirit is a novella set in Georgia's lowcountry. The Storycatcher is the second novel in the Black Mountain books.

Sleeping Above Chaos, the fourth book in the series, was a finalist for Georgia Author of the Year 2017 and also was a finalist in IndieFab in the Historical Fiction category. Where The Souls Go, the third book in the series, was a finalist for IndieFab in the Historical Fiction category 2016. Roll The Stone Away: A Family’s Legacy of Racism And Abuse was released by Mercer University Press in April 2020. She has stepped out of her box with her newest publication, the nonfiction narrative about Lucille Selig Frank. I can’t wait to find out more about Ann and her new book, so let’s jump in!

Ten years of research and writing went into your newest book, a biography titled, I Am A Georgia Girl: The Life of Lucille Selig Frank. Can you tell our readers a little bit about who Lucille was?

Lucille Selig Frank was born and raised in Atlanta. Her father, Emil Selig, immigrated to Atlanta right after the Civil War with his siblings. The Seligs are still known today in Atlanta for the real estate they own downtown and their philanthropic activities. Lucille’s grandfather, Jonas Cohen, was a co-founder of The Temple, the first Jewish synagogue in Atlanta. Lucille’s roots ran very deep in Atlanta. Lucille married Leo M. Frank in 1910. He was a Cornell University graduate in engineering. His uncle Moses Frank chose him to be the factory superintendent of The National Pencil Company in Atlanta, where Moses Frank was co-owner with Sig Montag. The couple had a promising future ahead of them.

When Lucille and Leo were married for two and a half years, things changed. On April 26, 1913, Confederate Memorial Day, Lucille asked Leo to go to the opera with her for one of the last shows before it left Atlanta. He declined, choosing to go into work because he had a business report due to his boss, Sig Montag. Had he chosen to go to the opera, life would have been much different.

The pencil factory was closed for a holiday so the employees could attend the Confederate Memorial Day Parade. Most employees received their pay on Friday evening, but a few who didn’t work on that day due to a brass metal shortage had to pick up their pay on Saturday.

Thirteen-year-old Mary Phagan came in for her pay around 12:00 pm on her way to watch the parade. Leo paid her, and the last he saw Mary, she was headed down the hall to leave the building. Mary never left the factory and would be found dead during the early morning hours of Sunday, April 27, 1913 by the pencil factory’s night watchman, Newt Lee. Leo would soon be arrested for murder and eventually found guilty of murder.

Leo was sentenced to death by hanging. Twenty-five-year-old Lucille fought long and hard to clear her husband’s name and save his life. She knew he wouldn’t have done the things Hugh Dorsey, the prosecutor, accused Leo of doing. Finally Governor John Slaton commuted Leo’s sentence to life in prison because he felt there wasn’t enough evidence to prove he committed the murder.

But this wasn’t the end of the story. A group of men from Cobb County, Georgia decided to take justice into their own hands. Leo was lynched in Marietta, Georgia—Mary Phagan’s childhood home—on August 17, 1915. One hundred and ten years ago, Lucille became a widow.

You believe, and I agree, that in the early part of the 20th century women were marginalized and oftentimes labeled as “hysterical”. But you know what a strong, courageous, and determined woman Lucille actually was. Her life ended in 1957, but if she were still alive today do you think she would face many of the same challenges now as she did all those years ago?

I love this question! One of the reasons I decided to write this book as nonfiction instead of my normal historical fiction was because so much of her story rings true today. Young girls and women in Georgia and throughout the South don’t know they have this strong woman—who lost everything—to learn from. Lucille’s story is not a happily-ever-after story. Yet, it is a story of strength. I think it is women like Lucille who paved the way for us to stand up and fight to be heard now. I would love to say that today we, as women, don’t have to fight as hard for our rights. But, this isn’t so. We still are marginalized to a certain degree, but here in the United States, we can stand up for ourselves like the women of the early 20th century have taught us.

Lucille would still face most of the same challenges today that she faced in 1913-1915. She is Jewish and threatening antisemitism is still prevalent today. Just look at our recent headlines. Women’s voices today, while heard, are still marginalized. Look at recent laws passed to control their choices when it comes to their own bodies. No, I think Lucille would be disappointed that history is once again repeating itself especially when it comes to women. If she were alive today, the PTSD from her horrible trauma would be more treatable. At least now we recognize the existence of the need to address mental health. Basically, everyone wanted to forget what happened to Leo and not talk about it. That must have been very hard on her. Lucille signed every document requiring a signature Mrs. Leo M. Frank throughout her life. I can’t help but believe this was a way to make people remember.

Your grandmother was haunted by memories of the lynching of Mr. Frank. Something she talked with you about when you were a young child and that, understandably, left a big impression on you. But there’s another connection to the people in the story that I think is one of those coincidences that seem to come from the universe. When did you learn that your husband is a cousin of Mary Phagan’s great-nephews? Is that something you learned during your research?

This is one of those dumb things that sat right under our noses, and neither of us paid any attention. When I began posting about Lucille on social media in 2015, one of my husband’s cousins, whom I had met, with the last name of Phagan—see how dumb it was we didn’t put two and two together—reached out to me. He asked if I was writing a book about Lucille. I said yes. He told me he had an original newspaper from the day of the lynching handed down in his family. He went on to explain Mary Phagan was his great aunt on his dad’s side. My husband is related to the cousin’s maternal side. I felt so stupid, and my husband felt even stupider. The Phagans believed and still believe today that Leo Frank was Mary Phagan’s killer. So, family wise, this was and is a slippery slope, but I did explain, I was writing this book about Lucille, who I felt was a victim as much as anyone else involved in this brutal set of events. She was a victim that never truly moved forward. I write at the end of my introduction the following:

“I am honored to tell Lucille’s story and the intersecting stories of other women. This research and writing taught me that we hold the power to make a change. What is the price of using this power? My great-grandfather believed in the mob’s right to take the law into their hands. How many were complicit in Leo’s journey? How many today choose to stay silent instead of speaking the truth? Don’t we owe future generations more?

This book leaves the decision to the reader.”

This section speaks for me, my grandmother, my husband’s connection to the Phagan family, and most importantly for Lucille.

I can’t wait any longer to ask this question. How did you come up with the title?

The first title was insanely clunky and downright terrible. I will not share it here. The marketing director, Mary Beth Kosowski, at my publisher, Mercer University Press, suggested we use “I Am A Georgia Girl.” This was a direct quote from Lucille’s last public statement concerning Leo’s lynching in the fall of 1915.

I had one of those moments of why didn’t I think of that? After all, I have a poem at the beginning of this biography that I wrote after reading her comment in the newspaper archives. This was Lucille’s way of reminding the public that they didn’t just do this to Leo, the Jewish man from New York, they did it to one of their own. Lucille was first and foremost a Georgia girl.