112 minute read

In Memoriam

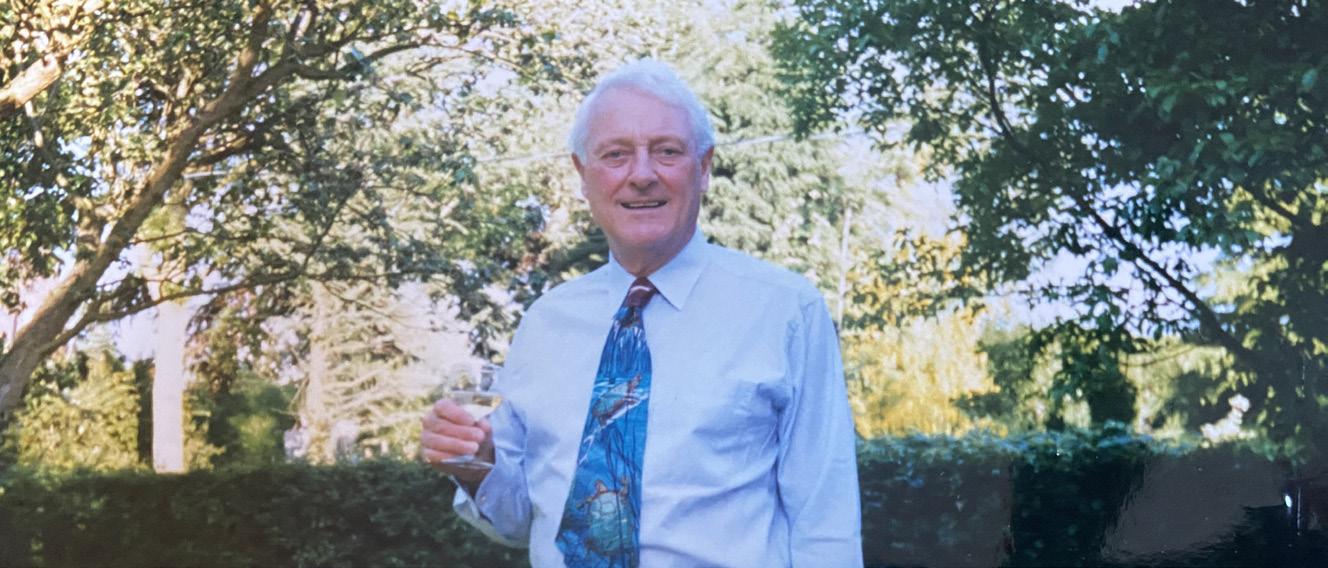

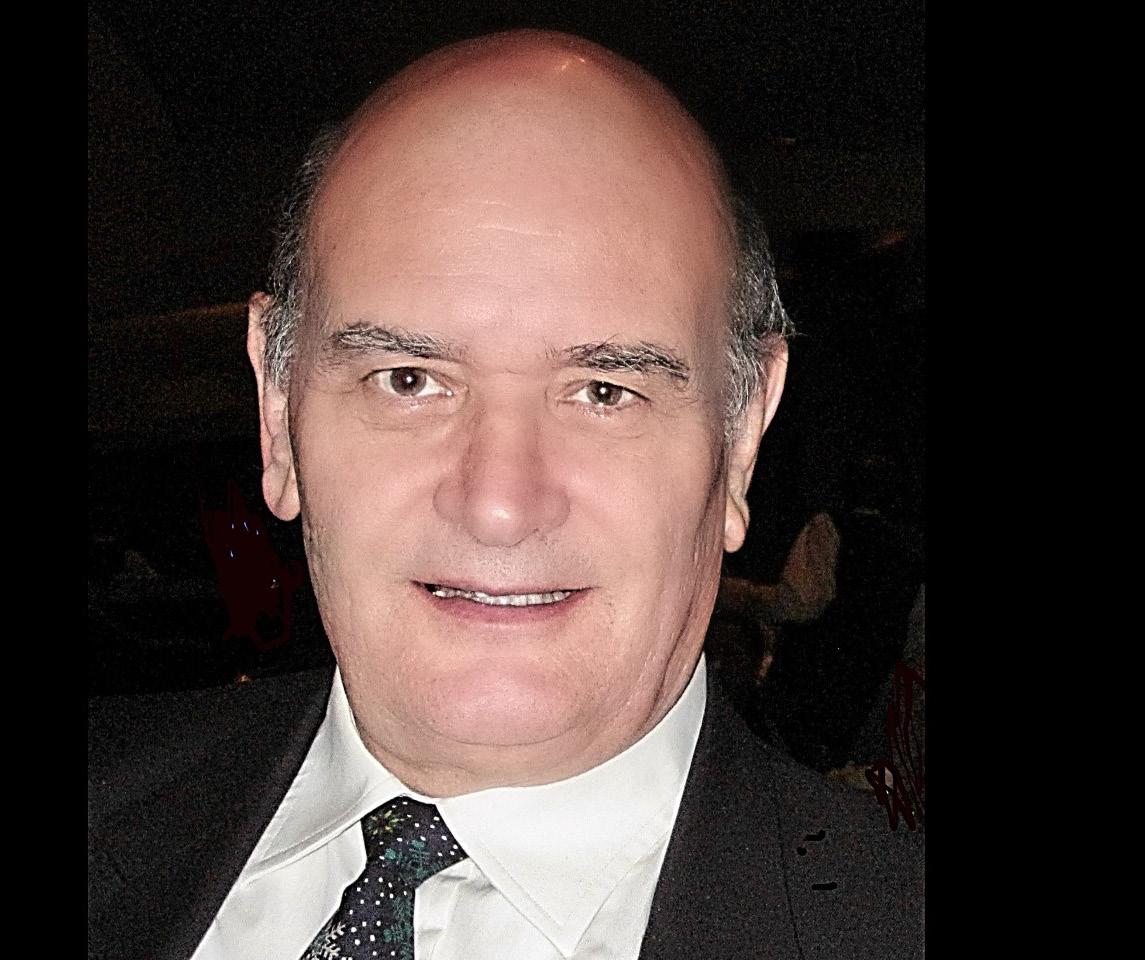

Bruce Wannell (S 70)

Bruce Wannell’s only attempt at a traditional career came in his early twenties when he signed on with the Inland Revenue to become a tax inspector in Finsbury Park in north London. The story goes that this unlikely calling ended after two months when, on his way up the stairs to resign, he met a man coming down the stairs to sack him.

Advertisement

From there Wannell, who was a free spirit, an outsider, and a man with a deep knowledge of the Islamic world, never looked back.

Inspired by a yearning for adventure and a dream of travelling around north Africa and south Asia that he had cradled since his undergraduate days at Oxford, he set off on what became a lifelong journey, developing skills along the way as a translator, lecturer and guide.

He was drawn perhaps as much by the mysteries of Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran and India as he was repelled by a bitterly unhappy relationship with his father, later replicated by strained relations with his two brothers. Wannell travelled like a Victorian and followed in a long line of eccentric English orientalists, embedding himself in the fabric of the places he chose to visit. This was exemplified by his lengthy residency in Peshawar in the late 1980s where he had initially worked for the British charity Afghanaid, assisting Afghan refugees.

That organisation was based in the genteel suburb of University Town, with its Englishstyle country villas and walled gardens, but Wannell soon opted for far less salubrious quarters downtown near the bazaar. There he was in his element, affecting local dress, speaking fluent Pashto, organising soirées at which Afghan singers and instrumentalists played and studying in preparation for his conversion from Anglicanism to Islam, which he celebrated with a circumcision party.

Wannell adored Afghanistan and travelled across it on horseback during the civil war, a feat that underlined that while he may have been something of an aesthete and most precise in dress and diction, he was tough and endured hardship and illness on the way with equal stoicism. His other great passion was Iran and the Persian language, which he read and spoke fluently among at least eight others, including Arabic and Urdu. He lectured on Persian poetry, mysticism and music and became an expert on Islamic epigraphy and calligraphy. He was in Iran teaching English and French at Isfahan University during the revolution in 1979 when a close friend was killed, an experience that affected him deeply.

This facility in Persian formed the backdrop to perhaps his greatest legacy, the work he did translating Persian and French texts for the celebrated historian William Dalrymple. Wannell worked with Dalrymple on all four of his histories of the East India Company, the first of which,White Mughals, is dedicated to Wannell. The two men worked together for months at Dalrymple’s farmhouse near Delhi where Wannell installed himself on his own terrace, creating his “Hanging Gardens of Bruce”, where he hosted Persian concerts.

Dalrymple revered Wannell’s depth of knowledge. “He was probably the best

translator of 18th century Persian,” he said of Wannell late last year. “He came and lived with me for six months, and we went through this stuff together, because he knows the language, but not the history, and I know the history, but not the language.”

However, it was more than just a working friendship, with Dalrymple calling Wannell “probably my best friend in the world” and a man he described as, among other things, a polymath, a perfectionist, an aesthete, a cosmopolitan bossy boots, an eccentric genius, a snappy dresser and “the kindest and naughtiest and funniest of men”.

Indeed, Wannell was all of those things, a man who was always on the move, almost always in need of a lift somewhere, often with little money in his pocket, but someone who was also a lover of the higher things in life: a great house in the country, tea taken on fine china and the chance to play a much-loved piano. He excelled at Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert and was an outstanding sightreader.

Wannell relied on the kindness of friends old and new and could become a fixture. On one occasion he was invited to look after a friend’s cat for three days and stayed for three years. Another long-time friend described the instinct of a cuckoo in Wannell. “Bruce would turn up and settle in and after a while you would notice that all the finest antiques had found their way to his room together with the finest china — after about a year you had a choice: either give in or tell him to bugger off.”

Another recalls Wannell housesitting for someone who left a full log store and wine cellar, only to return to find all the wine drunk and the wood burnt. Yet Wannell’s generosity of spirit earned him forgiveness for even his greatest misdemeanours.

Throughout his life he enjoyed visits to Hastings on the East Sussex coast, where his cousins lived and where he would dominate a weekend, organising swimming before breakfast, foraging expeditions for food in the countryside, a visit to the nudist beach, which he loved, and organising fishand-chip suppers, chased down with vodka, and then the inevitable musical soirée.

Great traveller that he was, it is perhaps surprising that Wannell did not leave more in the way of writing beyond his contribution to various academic texts on Islamic culture in Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan, Persian poetry, a guide to Iran and book reviews for the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of which he was a fellow. At one point he was paid an advance for a book on his travels in the Islamic world by his old friend Nicholas Robinson (obituary September 17th, 2013), but the project never came to fruition.

Bruce Azziz Wannell was one of four children of James and Andrée Wannell. He was born in Melbourne, Australia, in 1952, where the family had travelled to start a new life, but returned to England when he was just a few months old. His father was a businessman who worked for Unilever and a strict disciplinarian. Wannell fell out with him early on and the relationship never recovered. He was much closer to his mother, who was from Belgium and was a gifted pianist.

The family home was in Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, and Wannell was sent to Aldro preparatory school near Godalming and then Wellington College in Berkshire. He read French and German at Oriel College, Oxford, where he set up a madrigal society and threw outrageous parties. His study of West-östlicher Divan, Goethe’s collection of lyrical poems inspired by the Persian poet Hafez, proved seminal.

After Oxford, which had included a year in Paris, Wannell spent time in Italy and then Germany teaching English. In 1978 his elder sister Corinne, to whom he was close, took her own life after a broken love affair. This was particularly traumatic for Wannell who had to identify her body.

After two years in Iran, he took up the role of manager of the refugee office for Afghanaid in Peshawar working with Juliet Peck (obituary, February 23rd, 2007). Wannell developed close links with some of the more moderate resistance groups and also with western intelligence officers, latterly becoming a consultant to the UN and other agencies charged with monitoring aid projects for Afghanistan.

Wannell went on to work for the BBC World Service in Islamabad in the early 1990s, scripting Pashto and Dari programmes, including some increasingly racy soap opera-style dramas. He worked as a guide during the last 15 years, leading and guest lecturing on cultural tours to Iran, Central Asia, Egypt, Pakistan and India. He also taught Islamic calligraphy at Kabul University and for the Aga Khan Trust for Culture and lectured at Durham, Goldsmiths, University of London, and Oxford and the Institute of Ismaili Studies in London.

In recent years his base in Britain was a topfloor room in shared housing association premises in York. He made every effort there to engender a sense of community among his fellow residents and turned the derelict backyard into an attractive garden.

With fine, fox-like features, piercing blue eyes framed by white hair and a white beard and moustache, Wannell was always immaculately turned out. He enjoyed the company of women, but had no long-term relationships. Drawn to the Islamic faith through the Sufi poets, he found organised religion antipathetic to the soul and declared himself an agnostic in the months before he died.

A great walker, talker, cook and gardener, he used to think of himself as an autodidact. And his appetite for travel never left him. Even as he struggled with his final aggressive illness, he completed a trip to Chechnya, then led a tour through Iraq and was planning a trip to Somalia and Eritrea. He never made it.

Bruce Wannell, traveller, linguist, lecturer, guide and expert on Iran and Afghanistan, was born on August 25th, 1952. He died of pancreatic cancer on January 29th , 2020, aged 67

Article Courtesy of The Time’s

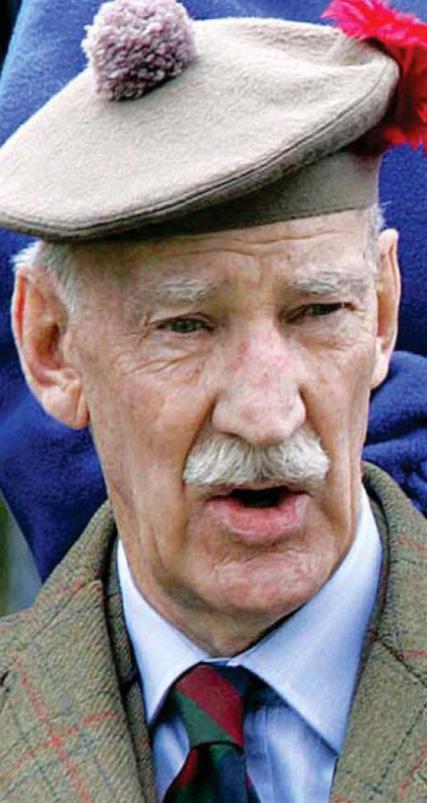

Arish Turle, MC (Pn 57)

Seeking adventure during the six-week summer break from Sandhurst, Arish Turle acquired a Foreign Legion uniform in Paris and joined a draft destined for Algeria. Challenged by an officer who did not recognise him, Turle gave his name. When asked, "Any relation to Rear-Admiral Turle?" he replied: "Ah, oui, mon commandant, he is my father."

It turned out that the commandant had been torpedoed during the Second World War and rescued by a Royal Navy ship that Turle's father had commanded. A celebratory drink concluded the matter. When he returned to Sandhurst to complete his officer training, contemporaries thought Turle so confrontational that they were surprised he survived the course.

Commissioned in 1959 into the Rifle Brigade, a regiment that welcomed strongminded officers of talent, Turle qualified for the Special Air Service and served first as adjutant of 21 SAS, one of the two Army Reserve units, before joining the regular 22 SAS. Described by a comrade as having a "Cromwellian complex", Turle was highly professional in his approach to soldiering. Yet, like Cromwell's alleged amusement before winning the Battle of Naseby, Turle could be found laughing when facing a dangerous situation. Once, when Turle and one of his SAS troop leaders were pinned down in a shallow-fire scrape in the Dhofar mountains with "green trace coming at them from 180 and 90 degrees simultaneously", Turle burst out laughing and muttered: "Maybe this is the end"

He was confident and well-reasoned about anything he faced, yet would react hotly if challenged, a habit that contributed to a growing reputation as a temperamental subordinate. Attending the Staff College in 1970-71 appeared uncharacteristic to his friends because it was an "establishment" sort of thing to do, an approach he ridiculed.

Recalled to 22 SAS before the end of the staff course, Turle took command of a squadron in Oman, where the regiment was engaged with the Sultan's armed forces in suppressing and eventually defeating the rebellion of the hill tribes in the southern Dhofar province. Armed and encouraged by the Marxist regime in adjacent South Yemen, the rebels had the advantage of a mountain range behind the coastal plain in which to take refuge.

The campaign appeared unwinnable until the adoption of a policy of persuading the rebels to change sides. The technique of persuasion began with digging wells for the hill tribes' cattle and teaching animal husbandry. Progress was slow, but some groups switched allegiance and were formed into "firqats", militia units that would defend The tribes against the Adoo, as the rebels were known. Tribal rivalry and blood feuds occasionally led to confrontation between firqats. As the SAS squadron commander responsible for overseeing several of them, Turle once flew into the hills and stood between two firqats facing each other with safety catches off. He held them apart with calming words for two hours, when one stray shot would have unleashed mayhem.

The "green trace" incident occurred after Turle feigned a withdrawal of his forces to lure in the Adoo. He stayed behind with a small, concealed party to bring down mortar fire when the Adoo advanced. Unfortunately, the Adoo sent forward a patrol to where the party was concealed, and a vicious firefight began in which Turle was critically outnumbered. By the sheer ferocity of his retaliation, Turle was able to hold the rebels off until air support, then ground troops, could be brought to his assistance. He was awarded the Military Cross for his fearless leadership.

Arish Richard Turle was the son of RearAdmiral Charles and Jane Turle, who gave him the unusual name of Arish after the Arish Mell Gap, the striking hill feature close to the family farm in Dorset. In 1964 Turle met Sue de Witt Brown at a London party and, despite her resolution not to

marry anyone in the armed forces because of the long separations involved, they wed two years later. They had a daughter, Serena, who owns and runs a chain of butcher's shops, and a son, Edward, who works in the jewellery business. All survive him.

In 1974 Turle was posted to HQ Northern Ireland as an intelligence staff officer with special responsibility for liaising with local and more broadly based intelligence agencies. This was a job ideally suited to his original way of thinking, but the potential for confrontation with colleagues was ever present owing to the sensitive relationships between the various agencies pursuing much the same objective. Details of what happened towards the end of this assignment are obscure but led him to look for something better to do.

Turle left the army in 1977 to join Simon Adamsdale, his former Royal Green Jackets and SAS comrade, at Control Risks, a security consultancy company. At the time the company was owned by Hogg Robinson, a Lloyd's of London insurance broker. Julian Radcliffe, a Hogg employee, suggested that a service could be supplied to kidnap victims who had taken out kidnap and ransom insurance from their syndicate. The company responded to the kidnap of a US citizen in October 1976 in Bogota, Colombia, and Turle joined halfway through the case. The victim was released after seven months when a reduced ransom was paid. Control Risks co-operated with the authorities throughout the negotiations, but to safeguard the hostage it arranged payment of the ransom without police involvement. Something close to military law was in operation in Colombia and a military judge ordered that Turle, Adamsdale and Jim Raisbeck, a prominent lawyer in Bogota, be detained and charged them with breaching counter kidnapping regulations. After 71 days in the Modelo prison they were released for the civil court to review their case. A further six weeks on bail followed before Control Risks employees were declared innocent, free to leave Colombia and welcome to return. The Hollywood film Proof of Life (2000), starring Russell Crowe as a former SAS officer, was based on these events.

Control Risks established an office in Bogota in 1985. During their time in Modelo, Turle and Adamsdale wrote the company's standard operational procedures for responding to kidnap, devised new Control Risks services and drafted the outline of a book on Kidnap and Ransom: The Response published by Richard Clutterbuck, a noted authority on political risks and violence. They also decided to initiate a management buyout of Control Risks, which was completed in 1982. The company has been independent ever since.

Turle was the managing director of Control Risks from 1978 to 1987, before joining Kroll Security International, an intelligence advisory company. His work for the firm led him to be based in Hong Kong and New York. In 1997 he started the Risk Advisory Group in London, retiring as chairman in 2004.

He bought a 90-acre farm in Somerset and raised alpacas there until last year, when the farm was sold. Despite these varied and demanding commitments, he maintained a close connection with former regimental comrades. Early last month Turle called one of his former troop leaders from Dhofar to say: "The doctor has given me a week to live, so I am calling to say goodbye."

Arish Turle, MC, special forces soldier, security operator and executive, was born on April 4th, 1939. He died of cancer on December 13th, 2019, aged 80

Article Courtesy of The Times

Captain Tim Ritson (Hn 53)

Captain Tim Ritson, who has died aged 84, brought inexhaustible enthusiasm to his various incarnations as cavalry officer farmer, fisherman and horseman.

Ritson belonged to that species of Englishman for whom "taking part" was the thing. Disappointments were not to be dwelt on and he had his share of those. A serious eventer in his younger days, he was selected for Great Britain's team at the Mexico Olympics in 1968, only for his horse to go lame, preventing them from competing.

Later, in 2001, he briefly had visions of immortality when he hooked a monster salmon ("It was like a shark'') on his beloved River Brora in Scotland. After he and his ghillie had played the fish for two hours, the nylon snapped. A few months later the salmon's carcass was found just below where they had lost it. Its weight was estimated at around 70lb, which would have made it the biggest-ever rodcaught British salmon, beating the record set in 1922 by Georgina Ballantine, who landed a 641b fish on the River Tay.

Neither of these setbacks could cramp his style. Timothy William Ritson was born on June 231935. He was five when his father, William, was killed fighting in North Africa with the 3rd Hussars, and his mother, Penelope, remarried a brother officer, Otho Bullivant. Tim, his brother Anthony and their half-brother Andrew were brought up in Dorset, and he was sent to Wellington College before going up to Trinity College, Cambridge, to read Engineering. His studies at Cambridge claimed less of his time than his duties as a whipper-in to the Trinity Foot Beagles and as double bass player in a Scottish country dancing band, and on leaving university he joined his father's old regiment.

During his decade in uniform Ritson's engineering skills were utilised in a fruitless attempt to develop a tank that could cross a river underwater. More to his taste, he represented the Army at polo (in the team captained by the Duchess of York's father, Major Ronald Ferguson) on tours of India and Kenya.

On the Kenyan excursion he was accompanied by his wife, Dawn, and one night they were woken in their tent by a Masai warrior brandishing a spear. "He wanted Dawn;' Ritson would explain. "I gave him a tin of beans and he left”. On leaving the Army Ritson settled on a farm near Malpas in south Cheshire, but his principal interests remained equestrian. He twice rode the Queen Mother's horse, Gypsy Love, around Badminton.

He also took his own horse, Evening Echo, to Badminton and, in 1966, to the first eventing world championships, at Burghley. It was on Evening Echo that he was selected to compete in Mexico. Hunting was another passion, and Ritson was known as a fearless rider across country with the Sir Watkin WilliamsWynn Hunt, for which he was a field master for many years. He also rode in point-topoints, and enjoyed team chasing into his late fifties, when a series of bad head injuries forced his retirement. For all his physical courage on horseback, he was nervous of hospitals, even stopping his surgeon from operating to remove the metal plates in his head after the administration of the pre-med. A devotee of Am-Dram, he produced many shows and revues in conjunction with local hunts. He also ran horse trials at Malpas, and built courses for team chases, hunter trials and the pony dub. Ritson kept body and soul together by selling turf and central heating oil from the farm, having experimented with various less successful ventures. He served for 25 years as a magistrate and chairman of the bench in Chester, where he was rumoured to be lenient when it came to speeding offences. An indifferent and adventurous motorist himself, he was once· stopped for speeding when on his way to preside in court.

He refused to holiday on a beach, since there was nothing to do, and was completely uninterested in material possessions. Shopping for clothes was an abomination, as all a man needed was a cap and a tweed suit. Tim Ritson married Dawn Johnson Houghton, daughter of the racehorse trainers Gordon and Helen Johnson Houghton. Seb survives him with their son Will, an investment manager in the City, and their daughter Jen, a hydrologist in New Zealand.

Captain Tim Ritson, born June 23rd 1935 and died September 2nd 2019

Article courtesy of The Times

David Arthur Llewellyn Brown (T 47)

David Brown was born on 19th November 1929. He followed his father (Maj-Gen R.Ll. Brown) to Wellington College, where he was in the Talbot. After leaving Wellington he did his National Service in Kenya, laying water pipes as a Royal Engineer. There is a story that his father the Major-General visited him training at the depot and found him cutting the grass with nail scissors; possibly apocryphal but likely enough for National Service.

Most of his uncles had, like his father, distinguished careers in the armed forces, government service or church. His grandfather most notably had been decorated with the Victoria Cross. Perhaps it was his own military experience that led him to pursue a career in the developing countries of the world, working as a tropical agronomist.

After National Service he read Agricultural Economics at New College, Oxford. This is when he met Priscilla, as he took up a room in Headington Vicarage, and took an interest in the Vicar's daughter. After Oxford he went on to King’s College, Cambridge to specialise in Tropical Agriculture.

David and Priscilla were married in July 1954 (this year they marked their 65th anniversary). Very soon after marrying, he went to Trinidad as part of his training and was unfortunate enough to contract Malaria. David went with Priscilla to Tanganyika in 1955 to work as a District Agricultural Officer in Mbulu, Moshi and Dodoma. It was in that time that their 3 sons were born — Alick, Richard and William.

On returning to the UK just before Tanganyika’s independence David worked for the Commonwealth Development Corporation (CDC) in London. The family then moved to Tawau in Sabah — the former British North Borneo, where David was working on Oil Palm and Rubber which were replacing Abaca.

Returning from Sabah to the CDC office in London in 1968, David noted that the same people sat in the same corner of the same compartment of the same train from East Grinstead as years previously.

In 1969 David was appointed by the Overseas Development Administration (ODA — now DFID) as Head of the Agronomy Division of the newly formed Cocoa Research Institute of Ghana, where he worked for 3 years, a period which included a military coup.

Following his work in Ghana, David briefly worked as a consultant to the Food and Agricultural Association (UNDP/FAO) in Indonesia on a mission to improve research on Rubber, Oil and Coconut Palms; later that year another ODA contract took him to the Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia in Medellin where he worked on coffee development and diversification for 3 years.

He returned to CDC as Senior Agriculturalist in London in 1976, retiring in 1987. He carried on working as an independent consultant variously for CDC, FAO and the World Bank until 1991; he was recognised as an expert in identifying land suitable to grow cocoa. This work included trips to Belize, Vanuatu, up rivers in New Guinea in canoes, and a similar trip to Costa Rica where a colleague commented on his knowledge and insight of St. John’s Gospel. It was not surprising that once settled back in England he trained as a Lay Reader.

Apart from his garden in Chelwood Gate, sketching and stamp-collecting, David’s interests after finally retiring included being a Lay Reader for the Chichester Diocese, and Secretary of the East Grinstead Citizens Advice. He also did volunteer work for the Stroke Association.

David Arthur Llewellyn Brown 19th November 1929 to 18th November 2019.

Prof Colin Pennycuick FRS (L 51)

Colin Pennycuick, who has died aged 86, was the pre-eminent researcher in animal flight over the last century. He focused on the flight of bats and birds (and their possible ancestors), and asked the question: how do they work? To answer this deceptively simple question he brought to bear a mix of sharp logic and original and practical invention.

Though he sought to ground his work in the rigorous application of physics and mathematics, he was not satisfied with abstract results and conclusions by themselves, but always sought to democratise his findings, first to the biological sciences community and then to the huge population of lay people fascinated with birds and their flight escapades.

Pennycuick was an expert glider pilot and gained some notoriety by piloting his craft in and around flocks of vultures, storks and eagles in Africa, and condors in Peru. The son of Brig James Pennycuick and his wife, Marjorie, Pennycuick was born in Windsor, Berkshire. His family followed his father’s army postings, which in 1938 took them to Singapore, which they left in 1941 shortly before the Japanese invasion. Pennycuick was later sent as a boarder to Wellington college, Berkshire, studied zoology as an undergraduate at Merton College, Oxford, and worked on his PhD at Peterhouse, Cambridge. There he studied muscle mitochondria, whose task of converting oxygen and nutrients into energy he viewed as the basic engine of flight.

During two years’ national service with the RAF, he flew Provosts and Vampires, early jet-powered aircraft. He subsequently worked as a postdoctoral fellow at the Animal Behaviour Laboratory in Madingley, Cambridge, and in 1964 began a long association with the zoology department at Bristol University as a lecturer.

The picture below is of Colin Pennycuick at work in Iceland in 1995. His career took him as far afield as Nairobi, Peru and the South Georgia Islands. Photograph: Sverrir Thorstensen

He used the first computer at the university to design a tiltable wind tunnel, which he built from scratch and hung in a stairwell. He developed and adapted aeronautical ideas from helicopter theory to bird flight and tested their application based on meticulous observations of the free-flying pigeons which he kept in a loft on the roof of the building.

In 1968 he travelled to Nairobi, which he made his base for three years, installing his tilting wind tunnel between two acacia trees to study bat flight in the same manner as he had previously done with pigeons. He then spent another two years in the Serengeti national park as deputy director of the research station there. He learned how to fly his powered glider alongside pelicans, storks and vultures, documenting for the first time their

extraordinary and essential abilities to travel economically over large distances by exploiting thermals.

From here on, his career was not so much a list of academic positions and research topics as a restless migration (frequently aerial, frequently self-piloted) of his own. He flew back to Bristol in 1973 via Addis Ababa, Cairo and Crete, in and around the Shetlands, France and Sweden, and down to Bird Island in South Georgia, Antarctica. There he first used his “ornithodolite”, an instrument he designed for measuring birds’ flight paths and speed, to track in detail the soaring flight of albatrosses. He found that the standard explanation — that they could power their flight by following a specific trajectory through a wind shear profile — was only partly responsible for their ability to fly continuously, without flapping, for very long times, and that instead they used the wind in several different ways.

In 1983, he left for Miami University, which became a handy launch point for expeditions to the Everglades, Tennessee, Pennsylvania and Idaho, and further afield in Puerto Rico, the Bahamas and Peru. In 1992 he left Miami, via Greenland, Iceland and Sweden. He began a continuing association with the animal ecology group at Lund University in Sweden, tracking migratory birds by radar, and in 1994 the bird flight wind tunnel was inaugurated there by the king of Sweden. In the late 1990s he collaborated with the Wildlife and Wetlands Trust at Slimbridge, in Gloucestershire, in tracking whooper swans, which as the largest flapping bird can provide a stringent test of aerodynamic theory at relatively large extremes of scale. He appeared in the 2003 BBC radio series Swan Migration Live, which tracked six Bewick’s swans and a whooper swan from Arctic Russia to the UK, with updates on their progress on the Today programme each morning.

In 2008 Pennycuick took part in an even bigger and more ambitious Radio 4 project, World on the Move: Great Animal Migrations, which tracked brent and white-fronted geese from the UK to Canada. With the aid of very accurate meteorological data, combined with measurements of wing beat frequency and wing shape, he modelled a gauge that could estimate the fuel consumed while these geese were migrating: this would give audiences, and the scientific community, some idea of the effort involved.

Pennycuick’s primary goal was to provide and test a physically reasonable theory of vertebrate flight, which could then be used to predict and understand how and why birds and bats do what they do. Many of his inventions, in techniques, procedures and instrumentation, were absolutely novel because he thought his own thoughts and proceeded by himself, according to the rigorous rules of logic and scientific inquiry. A rich and exuberant publication history burst from his activities, starting with the first practical flight theory papers in 1968 and going on to include the books Animal Flight (1972), Bird Flight Performance (1989) and Modelling the Flying Bird (2008). In later years he increasingly focused his efforts on his flight software package, which grew from a small custom Basic program to a rather versatile application with graphical interface. As well as biologists, engineers wanting to know how birds manage to achieve the things they do with apparent economy of effort and energy expenditure used the program, and both groups learned from it, which gave Pennycuick particular pleasure.

He was appointed research professor in zoology at the University of Bristol in 1993, and senior research fellow in 1997. He was elected fellow of the Royal Society in 1990 and was made honorary companion of the Royal Aeronautical Society in 1994. In 1996 he was awarded an honorary doctorate by Lund University.

In 1992 he married Sandy Winterson. She and his son, Adam, survive him.

Colin James Pennycuick, zoologist, born 11th June 1933; died 9th December 2019

Article courtesy of The Times

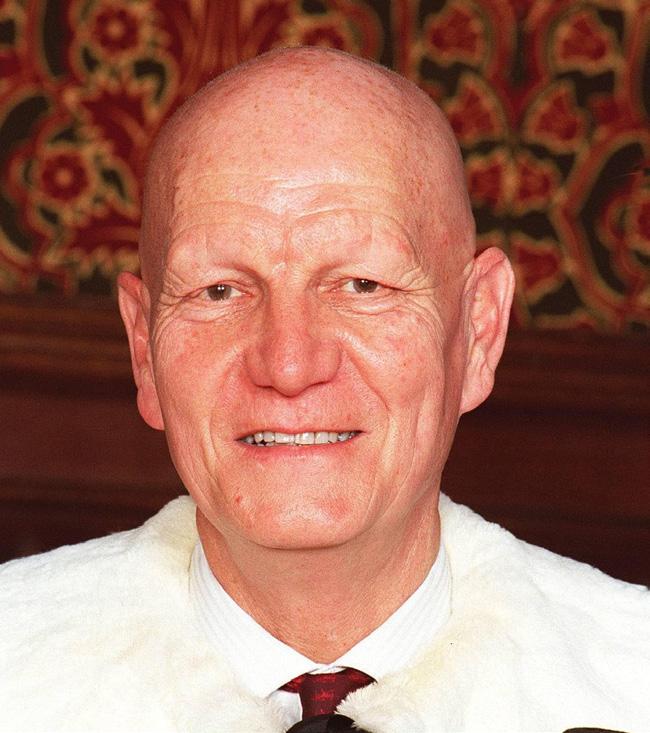

David Hopkinson (Bn 44) (Governor 1978-95)

As a lonely and unhappy child David Hopkinson comforted himself with his ability to memorise timetables across the entire railway network. Friends and family with a train to catch came to rely on his instant recall.

Hopkinson's gift would serve him well when he eventually found his metier in the world of investment in the City of London. As chief executive of M&G he would create one of Britain's fastest growing and largest unit trust groups.

Unit trusts had been created in 1931, but it was not until Hopkinson began to sell them in the 1960s as a way for the less well-off consumer to enjoy the full benefits of capitalism that the product became more popular. Under Hopkinson's vision, someone with as little as £10 (a much lower entry level than buying shares and without the need for a stockbroker) could invest in unit trusts rather than depositing small savings in a building society account.

"Hoppy", as he was known in the City, specialised in British stocks. At the root of his approach was his broad network of contacts across the country's industrial landscape who kept him informed of any signs of bad management in companies that M&G was invested in. "We were much better at spying than MI5” he joked.

M&G fund managers were required to know their companies from top to bottom and to undertake frequent site visits. They formed close associations with local stockbrokers based in industrial cities such as Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool.

Hopkinson abolished the research department so that the investment managers bought and sold stocks on their own information and responsibility. "The particular skill. was being well informed and having a sense of smell;' Hopkinson recalled. "Whether the managing director of a company had three wives or drank too much was really quite significant information ... the provincial stockbrokers actually often knew this because they played golf with these people and had a drink with them."

Hopkinson sounded like the quintessential old-school City gent; but he did not always look like one. Fashion did not matter to him and because of his scruffiness, on occasion, some people underestimated him. Like Lieutenant Columbo in his battered raincoat, Hopkinson turned his underwhelming appearance to his

advantage. He was also as shrewd as the television detective. Acting on intelligence, Hopkinson realised that all was not well at the washing machine company Rolls Razor,· which had drastically over stretched itself during the "washing machine wars" in the early 1960s. Paddy Lineker, who went on to succeed Hopkinson as chief executive. of M&G, recalled on his first day at the company being told by Hopkinson to start selling. shares in Rolls Razor, with strict instructions to "keep selling it and don't let anyone stop you': Not long afterwards, in 1964, the company collapsed. Hopkinson had joined M&G in 1963 when the company had £25 million of investment funds under management. When he retired at the age of 60, in 1987, the company was managing equity unit trusts for more than half a million people, and had £4.2billion under management with growth rates averaging 25.2 per cent per annum. Towards the end of his time in the City, Hopkinson began to recognise a penchant for personal greed, which would be exemplified by the character Gordon Gekko in the 1987 film Wall Street. "I've noticed young people — I'm not really blaming them — whose principal objective is to make money for themselves and they are not too fussy about how they do it. Whereas years ago, the principal objective was to make money for your client, and if you were good at doing that you would actually make money for yourself:'

Hopkinson was happy to retire in 1987, a year after the "Big Bang, which deregulated the financial ma a development he deplored, even though he compared the old stock exchange to a "badly run gentlemen's club". "I just thought [Big Bang] was a fashionable fad, with quite a lot of greed and envy;' he said, adding that he acknowledged that people would say "old Hoppy is on his warhorse".

David Hugh Laing Hopkinson was born in London in 1926 to Cecil Hugh Hopkinson, an antiquarian bookseller who specialised in musical manuscripts and had a shop in Mayfair, and Leila, nee Laing. His youth was troubled by the painful separation of his parents and his teenage years were blighted by the death of his beloved elder brother while on special operations in Tunisia during the war. He boarded at Wellington College and was then recruited into the navy in 1944 and spent two years minesweeping in the Bay of Bengal. He returned to finish his degree in modern history at Merton College, Oxford, and then joined the Civil Service and became a clerk in the House of Commons in 1948. Although he never really settled into life at Westminster, he did meet his future wife, Prudence Holmes, who was working at the Foreign Office. She survives him with their two sons and two daughters: Adrian, a stockbroker in Germany; Rosalind, a carer; Christopher, an airline pilot who also runs a ski chalet in France; and Katherine, a PA

A short spell at the Treasury made him yearn to be at the sharp end of commerce. He joined the merchant bank Robert Fleming in 1959, then moved to M&G in 1963, running the investment business for many years and going on to serve as deputy chairman and chief executive of M&G Group from 1979.

He was a financial adviser to St Anne's College, Oxford, at a time when the university was trying to imitate Harvard and pool all its resources into one large investment unit. Hopkinson took the unfashionable view that small units were just as effective, if not more so. Proof was in the success of St Anne's, which grew from being one of the smallest and most threadbare colleges at Oxford.

Hopkinson worshipped at St Nicholas Poling church in West Sussex, where he played the organ for nearly 50 years. He also played the clarinet. As a founder member of Chichester Cathedral Restoration and Development Trust he drove forward fundraising to restore the organ.

As chairman of the Chichester diocesan board of finance he once examined a quote that had been submitted by an American energy company to provide electricity for all the Anglican buildings in the diocese. Realising that the quote was ridiculously low, Hopkinson sniffed out wrongdoing. He also advised the Church of England not to buy shares in the company. Two weeks later, Enron became mired in a scandal when revelations of fraudulent accounting on a huge scale emerged.

M&G was acquired by the Prudential group at the end of the 1990s, but Hopkinson was delighted when it was demerged from Prudential last year, a testimony to the strength of the brand that he had helped to create.

In retirement he took on a wide range of non-executive board positions. He was involved in some 15 charities, including the Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, for which he was the first chairman after it became an independent museum in 1985. For many years he ran an arts and crafts centre at West Dean, West Sussex. The one-time train timetable fancier also sat on the board of British Rail (southern). He would drive between these many responsibilities in what was then a British-made and, given his career at M&G, appropriately named MG.

He was a Governor at Wellington College from 1978-95.

David Hopkinson, CBE, was born on August 14th, 1926. He died of heart failure on October 24th, 2019, aged 93

Article courtesy of The Times

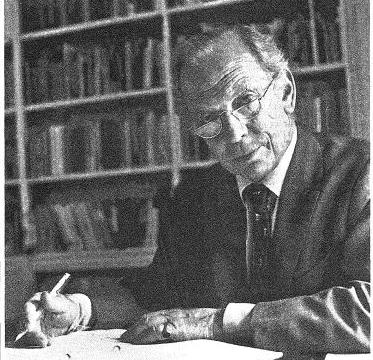

Frank Giles (Bd 37) (Governor 1968 - 1980)

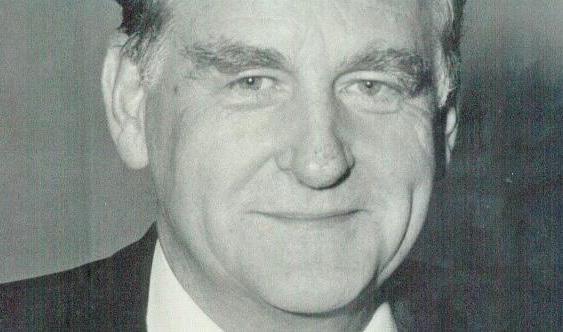

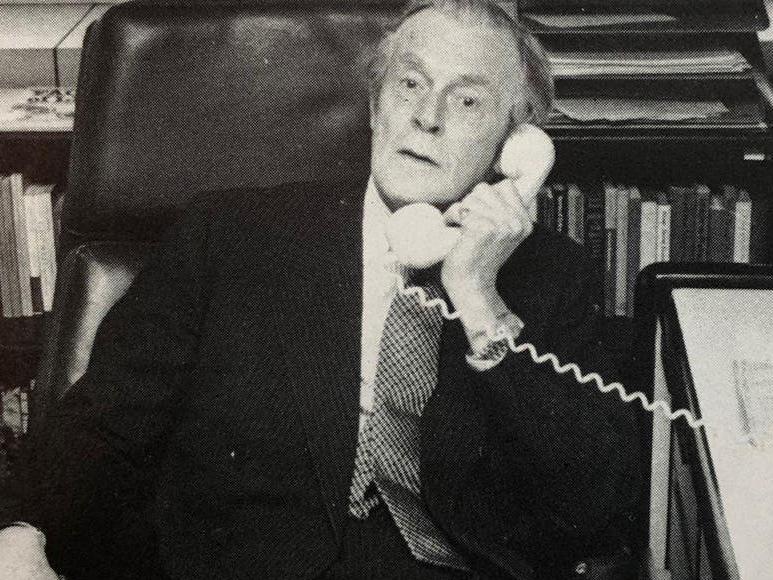

Frank Giles was one of the last of a particular breed of newspaper editors. Urbane, civilised and culturally aware, he served a lengthy apprenticeship as foreign correspondent for The Times and foreign editor and deputy editor for The Sunday Times before an unexpected, and turbulent, swansong to his career as editor of the latter from 1981-83.

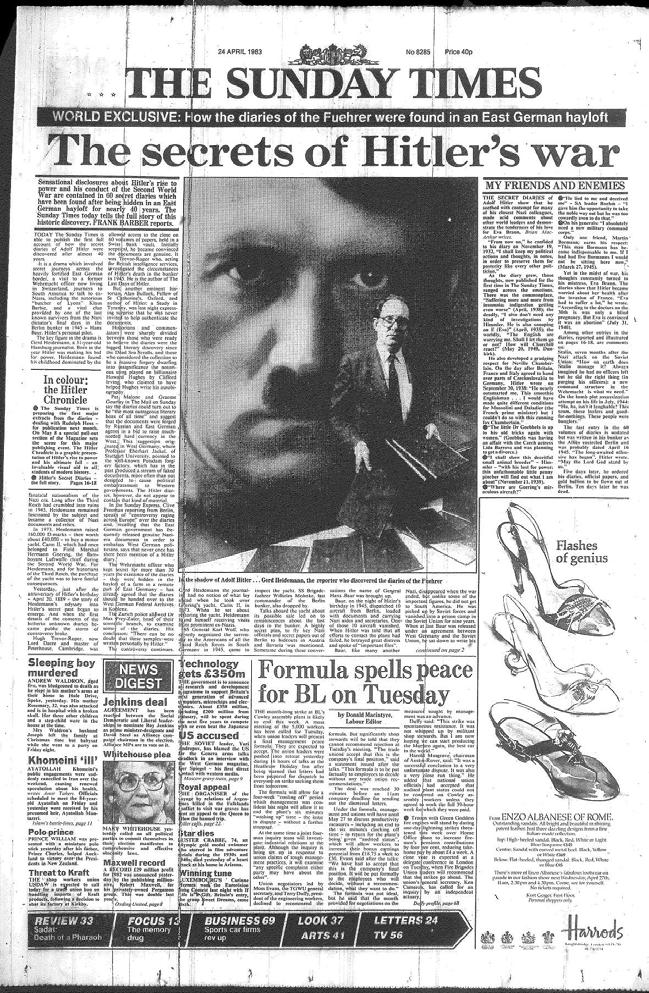

His short tenure in charge will be remembered for the traumatic episode of the forged Adolf Hitler diaries in 1983. The German magazine Stern had claimed to have discovered an extensive cache of the Nazi leader’s diaries and entered into negotiations with Times Newspapers Limited (TNL), the parent company ofThe Times andThe Sunday Times, about serialisation. The distinguished historian Hugh Trevor-Roper (by then ennobled as Lord Dacre), who was also a director of TNL, was called in to authenticate the diaries.

Dacre gave his enthusiastic assent, seized upon with alacrity by the papers’ management. But at the 11th hour, Dacre realised that he had made a significant error of judgment. By then The Sunday Times had committed pages to press. Giles maintained in his autobiography that he had been let down by Charles Douglas-Home, the editor ofThe Times, who had not passed on that Dacre was entertaining serious doubts until the die was cast.

Brian MacArthur (obituary, March 26), Giles’s deputy who had been intimately involved in the episode, wrote much later about that Saturday night as the presses were rolling. “As senior executives gathered with Frank Giles to discuss how to develop the story on the following Sunday, it was suggested we should get Trevor-Roper to rebut attacks on the diaries’ authenticity that would be unleashed by jealous rivals. As Giles was speaking on the phone to him there was a marked change in his tone of voice.

“The office fell silent. ‘Well, naturally, Hugh, one has doubts . . . but I take it that these doubts aren’t strong enough to make you do a complete 180-degree turn on that? Oh. Oh. I see. You are doing a 180-degree turn.’ ”

Giles felt deeply let down by the experience, and later wrote that he should have taken better account of the staff who had come to him with serious concerns about the veracity of the diaries. Indeed, one of his senior staff had drawn Giles’s attention to the similarities with a previous episode when Italian confidence tricksters had forged diaries purportedly by Benito Mussolini and had persuaded TNL to buy them. On that occasion, the ruse was rumbled before publication.

The Hitler diaries episode had come on the back of further industrial strife — to which both Times titles had become accustomed — after the new owner of TNL, Rupert Murdoch, had squared up to the trade unions. Murdoch threatened all the staff (journalists included) with summary dismissal if the National Graphical Association, which represented some of the printers, did not withdraw the threat that its members would strike unless given a pay rise. Giles was placed in the middle and did not enjoy the experience. He did, though, acknowledge much later that Murdoch’s battle with the unions over the move to Wapping in 1986 was necessary and right.

Frank Thomas Robertson Giles was born in London in 1919. His father, a colonel in the Royal Engineers, died when he was ten and his mother struggled to make ends meet. She took in paying guests while young Frank and his sister helped with the washing-up. Somehow, enough money was found to send him to Wellington College.

It was a tough school and an odd choice for a delicate boy, but he was excused from most games and made friends with other aesthetes equally out of their depth. He found an inspired teacher in Rollo St Clair Talboys, who helped him to win an open history scholarship to Brasenose College, Oxford. Giles, again an aesthete among hearties, was happy there until war broke out at the start of his third year.

He was unfit for military service, but his guardian, Major-General Sir Denis Bernard, took him as his aide — de-camp to Bermuda, where he had been appointed governor. So began a lifelong interest in current affairs and international politics. Among their first visitors were the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, en route to the Bahamas. The duke enraged the governor by remarking at dinner that if he had still been king, there would have been no war. He went further after the war, telling Giles in Paris that the war had been the fault of Roosevelt and the Jews. Giles nearly walked out, but decided that as a reporter it was his job to listen and record.

From 1942 he served in the directorate of military operations at the War Office, and in 1945 moved to the Foreign Office as a temporary civil servant, working in the private office of the secretary of state, Ernest Bevin. His vocation in diplomacy seemed plain, but to his disappointment he failed the permanent Foreign Office exam and for the rest of his life displayed traces of the diplomat manqué.

That disappointment surfaced occasionally in stories that, to his credit, he told against himself. Abroad on an assignment for The

Sunday Times, he made a courtesy call on the British ambassador who seemed more interested in how journalism worked than in international affairs. When Giles was taking his leave, the ambassador apologised. “I always wanted to be a journalist,” he said. “But I failed the Reuters exam.”

In 1946 Giles joined The Times, and the next year became its assistant correspondent in Paris. With him he took his new young wife, Lady Kitty, daughter of the 9th Earl de la Warr. Vivacious and charming, she was to become the unwitting cause of one of the best Giles anecdotes. When in 1950 he became the Times chief correspondent in Rome, a diplomat in the US embassy invited him to dinner and asked him to bring Mrs Giles with him. He explained diffidently that she was not “Mrs” Giles. That was perfectly all right, the American reassured him: “We’re broad-minded here. Bring her anyway.”

Giles stayed in Rome for three years and then became chief correspondent in Paris for the next seven. As a reporter in both capitals he was lucid rather than scintillating, trustworthy on his facts, objective in his verdicts, economical with his words, aiming to inform rather than entertain, always seeking the highest sources. He never wrote for the headlines. His first book was a lively biography of Henri de Blowitz, theTimes correspondent whose qualities were exactly the opposite of his own.

Because of his balance and detachment, he was often underrated. In 1960, however, Ian Fleming, still withThe Sunday Times despite the growing popularity of James Bond, told him in confidence that they were looking for a new foreign editor. Giles got the job and entered a dramatically different world.The Times in his time had been traditional, elitist, formal and hierarchical;The Sunday Times was innovative, populist, informal and classless.

Being at the heart of a paper was radically different from being at its perimeter; Giles picked up a piece of lead in the composing room and was advised by a printer, sotto voce, to put it down at once or the whole workforce would down tools. At first glance Giles looked too Woosterish to be taken seriously; he soon showed his mettle. His coverage of the Six-Day War, for example, was exemplary. Then, in 1967, when he began to work as deputy to Harold Evans, a close affinity sprang up between these two ostensibly disparate men.

Giles would have been many people’s first choice to succeed Sir Denis Hamilton as editor in 1967 when Hamilton moved to become editor-in-chief across bothTimes titles. “[Giles] was a most cultivated man, but as a newspaperman, though he had a safe pair of hands, he was not likely to run investigative journalism and take chances,” Hamilton wrote later in his memoirs. “He was not a natural leader, though unquestionably a man of integrity. On balance, despite my admiration for him, I felt he lacked the brio and sparkle thatThe Sunday Times needed to maintain the lead we’d sprung on The Observer andThe Sunday Telegraph.”

While Giles had been disappointed to miss out on the editorship, he worked hard and loyally as deputy to the younger Evans for 14 years. Giles described his editor as a cross between St Vitus and St Paul and noted that to say that Evans was energetic was like saying Goethe was literate or Einstein numerate. Both men had a keen sense of humour (Giles liked to refer affectionately to his editor to other members of the staff as “The Young Master”) and their rapport was total.

During these years Giles travelled widely; he interviewed the Chinese premier Zhou Enlai (easily the most suave and seductive statesman he had met) and President Reagan (whose answers were so bland he had to resort to asking him under which sign of the zodiac he had been born). He met the shah of Iran and Pope Paul VI, got

to know and admire the American art historian Bernard Berenson, but fell out with Nancy Mitford over his dislike for the French alexandrine poetic meter.

When Murdoch bought bothTimes titles in 1981, Evans was moved to the editorship of The Times and Giles, to his delight, but considerable surprise, was invited to take over atThe Sunday Times. Early on he encountered challenges, both from Murdoch and Gerald Long, the forceful managing director of TNL. It was the latter who proved the more difficult for Giles, with directives about changes to senior staff coming thick and fast. In mid 1983 Murdoch approached him about stepping down and Giles, perhaps wearied by the internal battles, agreed, becoming emeritus editor and relinquishing his chair.

The contrast between the public school educated, refined sophisticate and his replacement, the pugnacious Andrew Neil, was remarkable. In his announcement to the staff when stepping down, Giles commented: “I have to tell you that Andrew Neil, a man of whom I know nothing, has been appointed as editor.”

At his leaving function at the Reform Club, a young designer, grateful to the editor who brought him on to the staff, stopped him in the corridor to say thank you and began, “Frank, you won’t remember who I am . . .” to which the ultra-polite Giles replied immediately, “No, I won’t.” In retirement he wrote an autobiography, Sundry Times, giving his side of the story;The Locust Years, a first-hand account of the Fourth French Republic 1946-58; and Corfu, an affectionate portrait of the island where he and his wife had built a small, muchloved house among the olive groves.

His wife died in 2010 (obituary, August 7th , 2010). He is survived by a son, Henry, a furniture restorer, and a daughter, Belinda, a chartered counselling psychologist. His eldest daughter, Sarah, who had worked with Evans’s wife Tina Brown atVanity Fair, died in February 2014, aged 63.

Giles had a passion for classical music and as a young man loved to sing Bach and Handel in his fine baritone. He was a connoisseur of bordeaux and burgundy wines and enjoyed nothing more than giving small dinners when aged vintages from his cellars were enjoyed by likeminded friends.

While serving in Rome he became an admirer of Italian renaissance art, and was for many years a member of the Dilettanti Society, a group of art connoisseurs whose origins go back to the 18th century.

Frank Giles, newspaper editor, was born on July 31st 1919. He died on October 30th, 2019, aged 100

Article courtesy of The Times

Rosemary Irwin (Governor 2006-2016)

Rosemary Irwin was known at Marlborough College as "Doc Groves", a formidable deputy headmistress whose arrival in 1992 came shortly after the school had become fully coeducational. "I recall walking with her in Marlborough High Street, where she would pounce on unsuspecting sixth formers who were improperly dressed;' recalled one parent.

Those whom she taught included Kate Middleton, now the Duchess of Cambridge, and Princess Eugenie of York, both of whom she recalled as "very nice girls" though she was far too discreet to reveal what, if any, teenage antics they had engaged in.

It was through Irwin's association with Gilbert White's House, the museum in Selborne, Hampshire, dedicated to the 18th century parson-naturalist, that she entered the public eye. Her father had retired to a delightful thatched cottage in the village and she had long been vaguely involved, but after her retirement from Marlborough in 2005 she was recruited as a trustee and three years later became chairwoman.

The museum, which is also home to Captain Lawrence Oates's Antarctic memorabilia, was in trouble: displays had not been changed for years; tourists were increasingly choosing to visit the nearby Jane Austen's House museum; and all but one of the cottages that once formed its endowment had been sold off. Irwin immediately started reinvigorating the museum and its displays — and raising the money to pay for them.

Contacts were tapped, Heritage Lottery Fund applications successfully completed, letters written to charities and funding bodies, and partnerships built with the local council and other agencies. The everenergetic Irwin led from the front, including undertaking a 150-mile sponsored walk to Oriel College, Oxford, and back following a route once taken by White. It raised more than £30,000.

She also persuaded celebrities to visit, including the author Bill Bryson, who stopped by in April 2017 to open the Inspired by the Word art exhibition, and the Countryfile presenter Tom Heap, who in May 2018 re-opened the museum after a £3 million restoration.

The results of Irwin's decade as chairwoman of Gilbert White's House include a garden restored to its 1780s glory, the transformation of White's messy backyard into a new entrance, the creation of a restaurant out of the former stables, and a walk from the wooded car park behind the Selborne Arms that leads to the "zig-zag" path that White and his brother laboriously cut out of the hillside and which takes in views across the garden.

She also organised an exhibition dedicated to Frank Oates, the uncle of Lawrence Oates, who was also an explorer and in 1874 one of the first Europeans to see the Victoria Falls.

Rosemary Sylvia Helen Storrar was born in 1946, the only child of Robert Storrar, a housemaster at Wellington College, and his wife Joan (nee Pallister). She was educated at LuckleyOakfield School (now Luckley House School), Wokingham, which she hated, and Beechlawn, a tutorial college in Oxford that she adored.

She spent a year at the British Institute in Florence and then acquired office skills at St James's Secretarial College, Belgravia, before working for two dermatologists in Harley Street. In 1967 she married Richard Groves, a naval officer, and they settled in Portsmouth. He died in an accident in 1985 and she is survived by their two sons: Christopher, a lawyer, and Edward, who set up a recruitment company and who now lives in California. After her marriage she decided to improve her education and studied for a degree in history at the University of Southampton, graduating in 1972. She then began work on a PhD entitled "Poor laws in South Hampshire, 1870-1914", although the arrival of her family meant that it was not completed until 1991. Meanwhile, in 1981 she had completed a postgraduate certificate in education at King Alfred's College, Winchester (now the University of Winchester), and went on to teach history, politics and law at Peter Symonds College, a local sixth form college. During this time her father retired to Selborne, a village she loved not least, she said, because "it prides itself on being a dark village and we don't have streetlights".

She joined Marlborough College in 1992, serving as deputy headmistress and senior admissions tutor. In Michaelmas term 1999 she was acting master while Ed Gould, the master, was on sabbatical. In 2001 she was introduced at a dinner party to Rear-Admiral Richard Irwin and they were married five years later, settling in the cottage in Selborne that she had by then inherited. Irwin also survives her. Since 2009 she had been a warden at St Mary's Church, Selborne, where White is buried and is commemorated by a stained-glass window. When the 800-yearold church applied for a Heritage Lottery grant in 2016 she was able to bring from the museum her experience of handling the application process.

Over the years Irwin was a governor of 11 schools, including Wellington College, where her father had taught and she had been raised. Through this experience she perfected the art of directing an organisation without micromanaging the day-to-day details, a skill that she was able to deploy at Gilbert White's House with enthusiasm and seemingly effortless ease.

Rosemary Irwin, MBE, teacher and chairwoman of Gilbert White's House, 2008-18, was born on January 16th, 1946. She died of mesothelioma cancer on June 23rd, 2020, aged 74.

Article courtesy of The Times

James Montgomery (Pn 63)

James Montgomery who has died at his home in Hampshire was a well known face on southern television in the 1970s and 80s. With his charisma and creativity James made a successful career in broadcasting in both television and radio. Starting in children’s television in Sydney Australia, he found his niche as a news presenter and journalist in Hobart. After moving back to the UK he began his long association with Southern Television. An accomplished writer, director and later producer, between 1970 and 1989 he was a reporter and presenter for Southern Television and then Television South on programmes such as ‘Day by Day’ and the award-winning ‘Coast to Coast’ as well as many documentaries. Once his musical talents had been spotted, he presented the popular series ‘Music in Camera’ and forged a close relationship with the Bournemouth Orchestras working with the leading artists of the day to record and present opera and concerts on Television. Much to his amusement he also became the yachting correspondent covering various national and international sailing events.

James was one of the founders and directors of Ocean Sound; radio for the Solent region. Between 1994 and 2008 he wrote and produced several one hour documentaries as well as five series of six half hours for BBC Radio 2. Programmes included ‘The Danny Kaye Story’, ‘All Sail in Her (the story of the Queen Mary), ‘Howard Keel’s Playhouse’, ‘Dorothy Fields — First Woman of Broadway’ and the award-winning ‘Sammy Davis Jnr Story’.

The youngest of three children, James was born on 16th September 1945 in Wimbledon, London, to Feodora (the actress Jane Baxter) and Brigadier Arthur Montgomery. His school years were spent at Marlborough House in Kent where his early musical ability was recognised and nurtured. He went onto Wellington College in Berkshire where he excelled at music and developed his love of sound recording and opera. He was much in demand as a pianist in a band playing for society and debutant balls.

James went onto become an Academical Clerk under Bernard Rose at Magdalen College, Oxford. James was a member of The Madrigal Society in London since a young man until his death in 2019 and was president from 2005 to 2007. He supported young musicians at Wellington College and thoroughly enjoyed the annual Montgomery prize competitions, delighted and often astounded at the standards achieved by the students, he gave them much encouragement and advice.

After retiring James moved to Stockbridge, Hampshire and enjoyed a quieter life. He was a well known figure in Stockbridge Amateur Dramatic Society and joined several choirs in Winchester. He continued to write and lecture on a variety of subjects and his reviews of Stockbridge music concerts were much enjoyed.

James was a very special man, kind, gentle, and charming, with a lovely smile and a twinkle in his eye. His quiet sense of humour and knowledge on many subjects made him excellent company. A wonderful husband, father, brother and cousin James will be forever loved and missed.

James married three times, first to Carolyn Finlayson, second to Julia Harrison (the actress Fiona Richmond) and third to EmmaElizabeth Welman. He had a daughter, Tara with his second wife.

James Montgomery, 16th September 1945 to 16th November 2019

David Corsan (O 43)

Born 7th October 1925. Wellington College 1939-1943. Registered for the Navy (Fleet Air Arm) 1943. Two terms 1943-1944 studying law at Trinity College, Oxford, prior to reporting for duty. Registered for chartered accountancy articles with Coopers Brothers & Co 1944. After HMS Vincent, Portsmouth (shore training base), he was sent as one of a group of Fleet Air cadet pilots to the US Navy Air Force base at Corpus Christi, Texas, where he trained for seven months before receiving his ‘wings’ on VJ-Day 1945.

Post-WW2 he served on HMS Illustrious before in 1946 re-joining Cooper Brothers & Co which subsequently enjoyed a rapid period of growth and expansion over the next forty years. Having being appointed manager of the Sheffield office he became a partner in 1955 and returned to London two years later where he remained until his retirement in 1986. In his time he served as staff partner; on the Overseas Firms Committee for thirty years; as a foundermember of the Executive Committee in the early 1960s; and as liaison partner for South-East Asia, Australasia and the West Indies. For seven years he was the firm’s lead partner on a major World Bank project in Thailand, in constant liaison with the Thai Government and its officials amongst many others.

Among the many UK clients for which he was senior partner responsible were British Oxygen, BPCC, EMI, Clarke’s Shoes, Paul Hamlyn (Octopus Books), Staveley’s, Wilkinson Sword, Pergamon Press, Mirror Group Newspapers, Beefeater Gin and the White Ensign Association.

After his retirement from the firm he took up a succession of appointments, directorships and chairmanships — including with insurance firm John Poland & Co, the City regulatory body IMRO and the Brain Research Trust. He became an honorary Vice President for life of the White Ensign Association. After his wife Jeannie’s death in 2007 he founded the charity the Jean Corsan Foundation which provides grants for research projects into the causes — and hopefully eventually the eradication — of Alzheimer’s and similar diseases or conditions of the mind.

He was renowned for his team leadership, commitment, energy, dynamism, enthusiasm and directness. A keen sportsman, at 27 he had to retire from rugby — at which he had been a county player — because of a chronically-injured knee. Subsequently this joint could cause consternation or worse (some claimed deliberately) in an opponent by dislocating at any time without warning on the squash or tennis court until he finally had it replaced forty-nine years later.

David’s other great passion was sailing. He was skipper of his X One Design racing keel boat Skua at Itchenor in West Sussex for over fifty years and took business and holiday opportunities to sail in locations around the world. He served at different times as commodore of Itchenor Sailing Club, as both captain of the Itchenor XOD class and the national XOD Association, and was a founder-member of the Itchenor Society, designed to preserve the special nature of this sailing village.

He died on 9th February 2002 aged 94. He is survived by three sons, eight grandchildren and one great grandchild.

Geoffrey Ayscough Duncan Davidson-Houston (T 52)

On Sunday July 15th , 1934, JamesVivian Davidson-Houston wrote in his diary ‘a telephone call came at midnight [from the Argyll Nursing Home in Darlington] to say WE HAD A BOY, and all well’!

And so, the arrival of Geoffrey Ayscough Duncan DavidsonHouston, James and Cicely’s first son known to the family as Geoff, was recorded.

At the age of 3 months Geoff embarked with nanny and parents on the slow boat for Peking returning to England 4 years later with his mother younger twin brothers Ronnie and Mike while his father remained abroad, travelling extensively. They moved in as guests of family friends to Lartington Hall, then in the North Riding of Yorkshire. He attended Aysgarth Prep School and then Wellington College where he (told us?!) he excelled at Sport and Music.

In possession of an excellent singing voice, he was more than capable with the piano, the trumpet, the guitar, the zither and balalaika. His parents meanwhile were frequently stationed abroad, his fathers final posting being as military attached to Moscow in the 1950’s.

National Service, testing tanks, interrupted a budding career as an actor, writer and musician and he eventually settled in Seaford where life as a Prep School master at Stoke House suited him. He taught Latin and, of course, his beloved “games”. Here he met his wife Ann Coplestone and together they took on and ran Sutton Place school, a junior school later amalgamated with St Wilfrid’s another of the many prep schools.

Having left school life, the family moved to a smallholding in Lower Dicker with horses, ducks, geese and rabbits as well as dogs and cats. Once again, he embraced “the outside” with alacrity despite the early starts and a ‘day job’ in Local Government.

His career and managed both ended around the same time and through friends he began to recover his interest in the arts and continued love of the garden, his pride and joy not to say an obsession and the source of much of his happiness. Growing plants and combustion engines of all kinds proved a lifelong fascination as did a love of sailing.

As a result of gardening Geoffrey remained fit celebrating his 70th birthday with a day paragliding in the Alps.The day he died he had been working in the garden at Sutton Place: lugging, cutting, burning and tinkering in the time he had between endless cigarettes.

His two children: and five Grandchildren have not yet 'slung his ashes on the compost heap' per his instructions … but may well do so in time.

Michael Westropp (A 56)

Mike was an active member of our Club for many years, latterly helping as a Committee Member, and his contribution and companionship will be sorely missed. A retired Marine Engineer, Mike had a passion for the Thames, which must be why he had a troublesome slipper launch, something to tinker with as he generously offered trips on the river. His pride & joy, The Swan of Thames, will also be missed, at our regattas chasing down the competitors in their finals, as well as parading in the Thames Traditional Boat Festival at Henley.

Mike was a quintessential English Gent, with his jaunty boater & cheeky smile, he will undoubtedly be sadly missed by his wife Judith, family & the many friends that he had both at The Skiff Club & at Walbrook Rowing Club.

Jan Hildreth (O 51) Governor (1975-2005)

Thank you for joining us today to say goodbye to Jan:

• husband to Wendy,

•father to Gerald, Frances and myself;

•grandfather to Jemima, Imogen, Millie,

Monty and Minty;

•and brother to Gillie, Jenny and Johnny who are here today and Judy and Anne who, sadly, are not.

•He was also, of course a father-in-law to Jodie and Grim, an uncle, a godfather, or a cousin to some of you and a friend, colleague, neighbour and running companion to many more.

I am going to refer to my father a ‘my father’ throughout my eulogy. But I would like to feel that I speak on behalf of Gerald and Frances. As such, I did wonder about using ‘our father’ but, in the context of a church service, that seemed to risk putting him on a pedestal that exceeds even my father’s highest aspirations.

My father and mother fell in love at Oxford, introduced by her brother Quentin with whom she shared a flat. He and Quentin had become firm friends during their National Service. As a former head boy and keen athlete, it is probably no surprise that Dad enjoyed national service and subsequently chose to serve in the TA, joining the Royal Horse Artillery Parachute Regiment. This provided lively anecdotes and lifelong hip pain from parachuting injuries.

When they met, my mother had recently returned from two years living the high life in 1950’s Manhattan, where her father was the Finance representative for Great Britain in the United Nations.

Their first meeting was not auspicious. Accustomed as she was to the abundance of New York, she proudly served him a gristly British braising steak, expecting it to taste like American filet. He apparently pointed out her error with glee and then made a great show of chewing his way through it with grim determination. Her fury was further compounded by him teasing her about her strange New World clothes. Nevertheless, my father, had a sports car (albeit generally in pieces) and a sense of humour, and the rest is, of course, history.

Not everybody thought it was a good match. My grandmother swore it would never last; but that was one Christmas in the 1980’s by which time they had been married for 30 years.

They celebrated sixty-one years together last year and I may have missed something but I have never had the slightest doubt about the depth of that love they shared.

To us as children, our parents’ lives appeared to be charmed and full of excitement.

We heard about their years in the Philippines, where Gerald was born. That story was, of course, more complicated than I understood at the time, but their tales of tropical life and encounters with pirates, gangsters, cannibals and money laundering nuns served as a challenge to go out and experience all that the world has to offer.

When we were growing up, Dad was never happier than when he was building things: longbows from the exotic hardwoods he had brought back from overseas; exquisite model aeroplanes; furniture (in the days before IKEA); and, not least, 43 Ridgway Place where we all lived just long enough for the dust to settle before he bought Number 50, the house he and my mother spent the next 48 years in.

Endlessly busy; when he wasn’t building things, he was taking and developing photographs, obsessing about windmills and renewable energy, planting fruit trees, collecting antique furniture and tools and buying and endlessly renovating the mill on Dartmoor.

His creative talents did not extend to the kitchen I am afraid. He was colour blind and I sometimes wondered if this condition somehow included to his taste buds. He enjoyed good food but often felt the need to check with my mother whether he was eating chicken or fish. I was discussing this with Frances the other day and we could only remember him ever making three meals since the first moon landing. And one of those doesn’t count as it involved frying Christmas pudding; in butter. [He was very enthusiastic about pickling the walnuts which grew in the garden; not because he liked eating them — they were absolutely vile and he never touched them — but to frustrate the squirrels who otherwise would have stripped the tree bare.

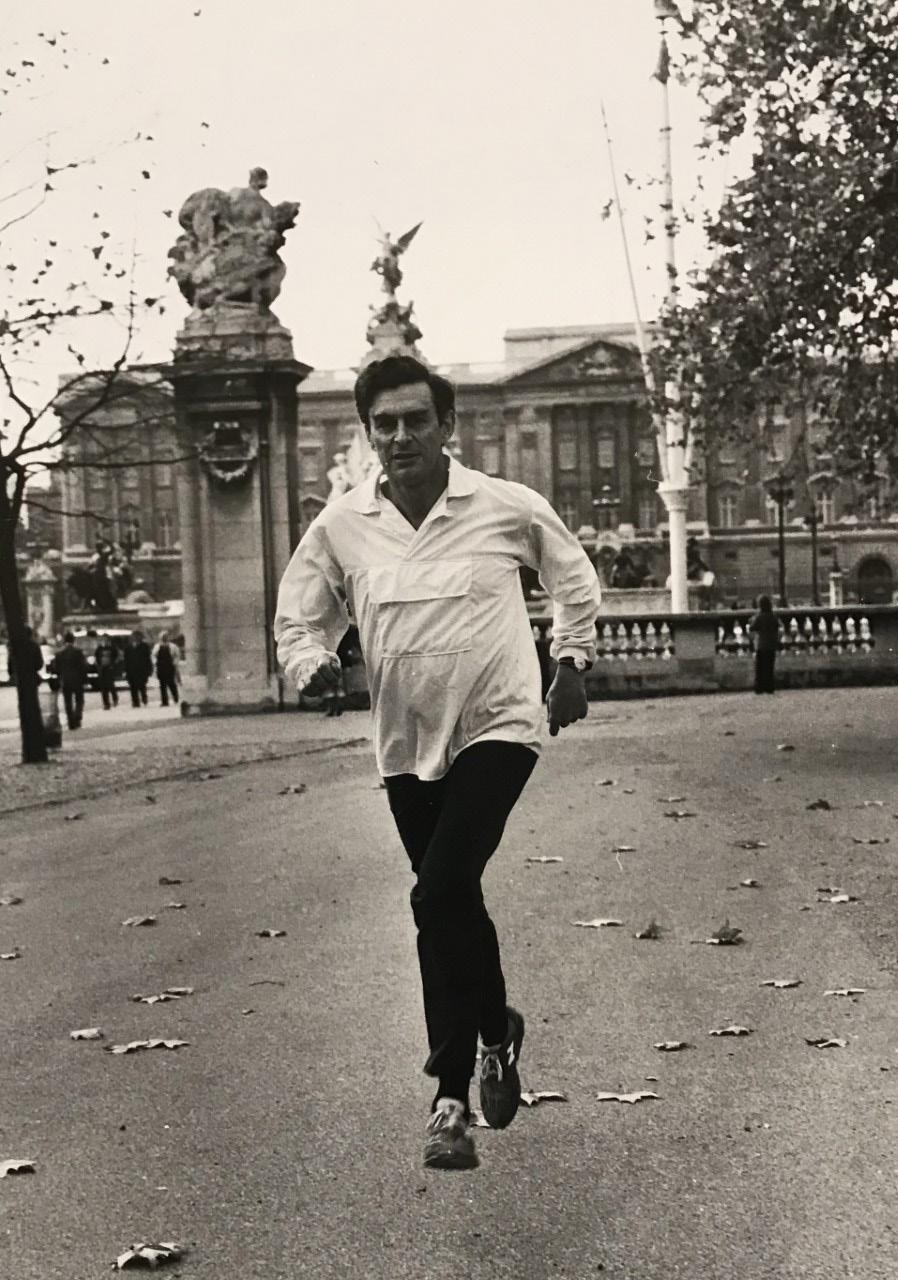

The love of running my father discovered at school never left him. A member of Thames Hare and Hounds for as long as anyone can remember, the club was where he forged many great friendships. It has been lovely to hear from so many people about their fond memories of Wednesday evening runs and Saturday matches running with him. Running was how he relaxed and how he developed his thoughts. To be fair, some of his friends used to complain that this could be exhausting. For my father running was a form of thinking and thinking involved talking. Non-stop. All the way round.

The Club’s traditional 8 to 10 mile stretches across Wimbledon Common and Richmond Park were overtaken by marathons in the early ‘80s which my father and the rest of the club took to with baffling enthusiasm. He ran his first at the age of 48, in 3 hours 25 minutes, and was one of only 28 people who completed the first 25 London marathons. [I was remined after giving this eulogy that, this was just the beginning and he subsequently achieve a string of sub-3 hour marathons.

Although much of his career was in Finance roles, my father really preferred to see himself as an economist. Restless and curious, he was driven by the need for intellectual challenge. The range of roles he took on and thrived in, is extraordinary even by today’s standards where we expect to chop and change as we go. From the National Economic Development Council to Shell (in Finance and oil sales), to London Transport, the Institute of Directors where his campaign for free enterprise and what he saw as economic common sense helped usher in the Thatcher era and Minster Trust where he passionately championed the growth of small businesses all over the country (scallop and salmon farms, early drone technology and climbing walls amongst many others).

Alongside all these, he held long term roles as a governor of Wellington College and as a director of Finance for Scope the charity for people with cerebral palsy.

Later on, when my mother might have reasonably expected he would retire, he devoted himself passionately to providing sound financial control to two NHS trusts, giving them the resilience to cope with the changing whims and funding of their political masters. It was only with great reluctance, when in retrospect his condition had taken hold, that he let go of the world of work. I am not sure he would ever have retired otherwise.

Dementia is cruel but my father bore it with great dignity. We should not let it define our memories of the person behind the condition. Even in the later stages he would light up when friends and family Today is the 31st of January; a day of departure if ever-there-was-one. My father’s final illness was so much less than the sum of his life. Today, is the day we can leave it behind.

One of the pleasures of the last few weeks has been to read the dozens of letters which remind us of a life lived with passion, zest and humour. They recall his energy, kindness and thoughtfulness, his lack of stuffiness; how valued his support and advice were to friends and colleagues; his sense of fun, his integrity, his love of company and the lively twinkle in his eye.

I can’t do better than to close with the thoughts of one of his old friends, Bill Dacombe:

“We all remember him as a vigorous, energetic man, full of life and drive ... when he came into a room there was a raising of everyone’s spirits, a brightening of the atmosphere. Many people are energetic but few have that talent to raise others’ spirits to their level and Jan certainly had it. And that is the Jan that everyone will remember”

Major Adrian Gillmore MC (HI 46)

Adrian was born on 28th June 1928 at Murree in North India (now Pakistan) while his father was stationed with the Indian Army.

As was the way in those days Adrian was brought to England at the age of six and left at a pre prep boarding school, not seeing his parents for another year, when they returned to England following his father’s retirement from the army. Adrian then went on to St Dunstan’s prep school in Burnham on Sea and entered Wellington College in 1941. He left in 1946 to enrol at The Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, being part of the first intake after the war. He then joined the 1st Battalion of the Suffolk Regiment based at Bury St Edmunds.

Adrian’s first posting was to Athens, and then with his platoon, he was sent to Malaya in 1949. There he saw combat in the Malayan Emergency and was awarded the Military Cross while he was Platoon Commander. He was always very reticent about that time and the records that his mother kept have quietly disappeared, although he always wore his medals with pride on appropriate occasions.

He returned to the depot at Bury St Edmunds as Training Officer but then volunteered to learn Finnish. This proved to be a very difficult language to master but his nine months in Jyuaskla, Finland was a happy time. He made many long-term friends and had plenty of opportunity for sailing and cross-country skiing.

On his return to England, being a bachelor, Adrian was dispatched to a remote police station in Malaya for a three-year posting, with no home leave. As well as giving him a taste for oriental food this second stint in Malaya allowed him time to study for the entrance exams for Staff College at Camberley which he entered in 1961.

By now the Suffolk Regiment had combined with the Royal Norfolk to become the 1st East Anglian regiment based in Harwich in Essex.

Problems of rioting and discord had arisen in British Guyana so the Regiment was sent on an emergency tour at such short notice that they were very short of equipment and had to make do.

In 1962 Adrian was stationed at Felixstowe as Rifle Company Commander and found time to sail his boat on the river Orwell.

Further postings were as a Staff Officer in Intelligence in Borneo which had been invaded by Indonesia in 1963-4, followed by two years with the Regiment in Benghazi which gave ample opportunities for water skiing and trips into the desert. On his return Adrian was posted to the Royal Leicestershire Regiment TA as 2 in Command Training Major where he made many lifelong friends.

Adrian’s final posting in May ’67 was to Malta as Company Commander C Company of 1st Battalion Royal Anglian Regiment. There he bought an aluminium speed board for water skiing which was shipped back to England amongst the regimental equipment. This boat was to play an important part in his life! Adrian returned to his home in Stoke Gabriel in South Devon to take over the management of his father’s small farm and herd of pedigree South Devon cattle, first of all studying for a year at The Royal Agriculture College Cirencester. Known as the ‘British Legion’ by the younger students at Cirencester, Adrian was part of a cohort of mature ex-army officers pursuing a new career in the prosperous business of farming as it was at the time.

He had hardly settled into his new life as a farmer when the chance of some water skiing attracted the interest of a longtime family friend, Jane Bayly. Together they prepared the Maltese speed boat for action and within a month Adrian finally plucked up the courage to pop the question.

Jane’s parents, who had been farming on the coast at Kingswear, had just put their farm on the market so Adrian had to decide rapidly if he could take on the extra responsibility of a 300 acre farm nine miles away from Stoke Gabriel. But the decision was made. Adrian and Jane were married in March 1970 and lived at the Kingswear farm for 10 years where their three sons were born.

Unfortunately, Adrians’ increasingly arthritic hands, legacy of a motoring accident in Malaya, made mixed farming, lifting hundreds of bales and wrestling with sheep and cattle, an impossibility. In 1979 they sold the Kingswear farm to the National Trust, who wanted ownership of the ¾ mile coastline, and Adrian made the sad decision to sell the majority of his carefully bred South Devon polled cattle.

The family moved to a tumble-down farm on the banks of the nearby river Avon, nine miles west of the Dart Estuary. The land was neglected and the medieval house in a dilapidated state. But after two years of ‘camping’ in the house, surrounded by builders, the place was transformed into a beautiful family home. Meanwhile, with a lot of hard work Adrian brought the land back into control, taking in other people’s cattle for eight months of the year under the system called ‘Grass Keep’. He was an active member of the South Devon Herd Book Society and had retained a nucleus of his best pedigree South Devon cows as a suckling herd. These were kept at the Stoke Gabriel farm under the care of the stockman who had worked for the family all his life. One of the steers was awarded ‘Best in Show’ (of all breeds) at The Smithfield Fatstock Show in London in the year 1995. Finally, Adrian sold all the cattle in 2005.