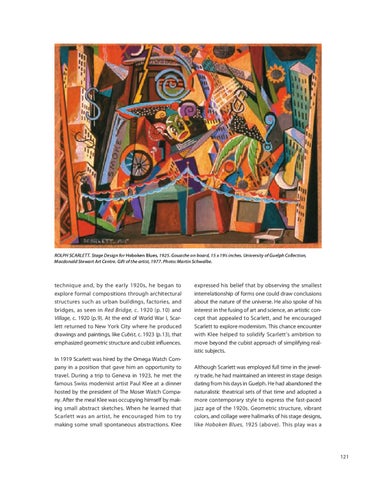

ROLPH SCARLETT. Stage Design for Hoboken Blues, 1925. Gouache on board, 15 x 193â „8 inches. University of Guelph Collection, Macdonald Stewart Art Centre. Gift of the artist, 1977. Photo: Martin Schwalbe.

technique and, by the early 1920s, he began to explore formal compositions through architectural structures such as urban buildings, factories, and bridges, as seen in Red Bridge, c. 1920 (p. 10) and Village, c. 1920 (p.9). At the end of World War I, Scarlett returned to New York City where he produced drawings and paintings, like Cubist, c. 1923 (p.13), that emphasized geometric structure and cubist influences. In 1919 Scarlett was hired by the Omega Watch Company in a position that gave him an opportunity to travel. During a trip to Geneva in 1923, he met the famous Swiss modernist artist Paul Klee at a dinner hosted by the president of The Moser Watch Company. After the meal Klee was occupying himself by making small abstract sketches. When he learned that Scarlett was an artist, he encouraged him to try making some small spontaneous abstractions. Klee

expressed his belief that by observing the smallest interrelationship of forms one could draw conclusions about the nature of the universe. He also spoke of his interest in the fusing of art and science, an artistic concept that appealed to Scarlett, and he encouraged Scarlett to explore modernism. This chance encounter with Klee helped to solidify Scarlett’s ambition to move beyond the cubist approach of simplifying realistic subjects. Although Scarlett was employed full time in the jewelry trade, he had maintained an interest in stage design dating from his days in Guelph. He had abandoned the naturalistic theatrical sets of that time and adopted a more contemporary style to express the fast-paced jazz age of the 1920s. Geometric structure, vibrant colors, and collage were hallmarks of his stage designs, like Hoboken Blues, 1925 (above). This play was a

121