Examining Conversions

Conversion projects have been around for decades. Contemporary architectural gems in many American cities are the result of thoughtful conversions. It is heartening for a community’s old fire station to be repurposed as a restaurant, or when a shuttered mill is reimagined as an office building. The American Tobacco Campus in Durham, NC, was transformed from an abandoned, century-old factory to a thriving mixeduse work and entertainment destination.

The current Waldorf Astoria is a GSA-led transformation of the government office in the Old Post Office Building to a WDG designed luxury hotel. High-rise office buildings like Dallas’s Santander and Bryan Towers had WDG convert thirteen floors into luxury apartment and extended-stay guest suites, maximizing the building occupancy rates. Developers are repurposing schools, offices, churches, and even old corporate headquarters.

Converting office to other occupancy can address housing supply shortages and help bring back commercial business districts.Waldorf Astoria is a Government Office conversion to a luxury hotel.

Adaptive reuse architecture is a creative and specialized challenge. The pressing trend is to convert office buildings into multifamily residential or hospitality properties. These designs are a purposeful solution, more environmentally sustainable and offer more vibrancy to obsolete, underutilized, and often vacant buildings. Downtown Washington, DC, revitalization lags as the city slowly recovers from a post-pandemic workforce fixated on remote work flexibility. Conversions could be the solution that solves two problems for city governments. Converting office to other occupancy can address housing supply shortages and help bring back commercial business districts. Entire commercial districts can be revitalized with residences to create 24/7 mixed-use communities.

In today’s market, there may be an understandable trend to view many office properties as conversion opportunities. Understanding basic concepts of conversions is critically important, valuable, and timely to development professionals, city officials, and local communities. Each potential property needs to be evaluated on its own merits to determine the probability of success, and whether the location, costs, timing, and existing building layout make sense for a conversion. A strong recognition of the priorities and best practices can be tips to executing a successful office-to-residential redevelopment. This intriguing development sector has revealed several considerations.

Conversions work best for both developers and communities when aging, under-optimized buildings are converted to accommodate higher-demand use. Taking underutilized space off the market bolsters demand for remaining properties in that segment, which lowers the vacancy rates. Newly converted space can fill a higher demand market need while relieving tax pressure. The improved functional spaces increase the tax base for taxpayer and municipality benefits. The properties utilize the existing public infrastructure, roadways, transportation network options, and utility connections for a rapid reconnection of an existing community.

Prepare Now

Office occupancy hovers around 45% in many jurisdictions. As people opt to work from home, downtown economies are collapsing. Cities are scrambling to stop the deterioration of their tax base. Buildings are vacant, storefronts are empty, and commercial value is down. Retail dead zones can increase the perception of uncertainty and rising crime, discouraging current tenants and future investment. Transitional properties cannot afford to take decades for investment—this action is linked to shorter election cycles and annual company pro formas. Incentives must be immediate to spur these long-term projects.

Geography and Geometry

Converting office to residential sounds simple in concept, but the execution is complicated. Architects can fix a property, but they cannot fix a location. There are exceptions—when a large project is so consequential that it has broader transformational impact. The old U.S. Coast Guard Headquarters at DC’s Buzzard Point is a conversion catalyst for an entire new residential neighborhood.

Older Class C office buildings are prime conversion targets; but, for most developers, the success of a conversion project is highly dependent on its location. The other key element to make the conversion process work is the right building. Older buildings often benefit from centralized locations and smaller, more desirable floorplates and conventional window openings. Older buildings also have an advantage for conversion because maintenance has often been deferred, warranting a full electrical, HVAC, and plumbing renovation for the new use. Finally, structural alignment can add further difficulty.

Design Considerations

Successful and cost-effective conversions rely upon due diligence from the developer, design, and construction team to understand the existing building infrastructure. A discovery process will help the team understand how the building will perform in its new function or increase in size or allowable density. The ideal floorplate depth for a double-loaded residential corridor layout is sixty-eight to seventy feet. Older office buildings designed for multiple tenant floors often have stacked floors with narrow configurations—attractive for apartment conversions. The column configuration in these buildings is smaller in dimension—often a 20’ by 20’ grid—and suitable for basic residential unit layouts. Designing residential living spaces with existing columns and cores requires knowledge and expertise of current building codes and regulations and awareness of environmental context. The existing structure should also have a code assessment completed to confirm the new use and occupancy requirements.

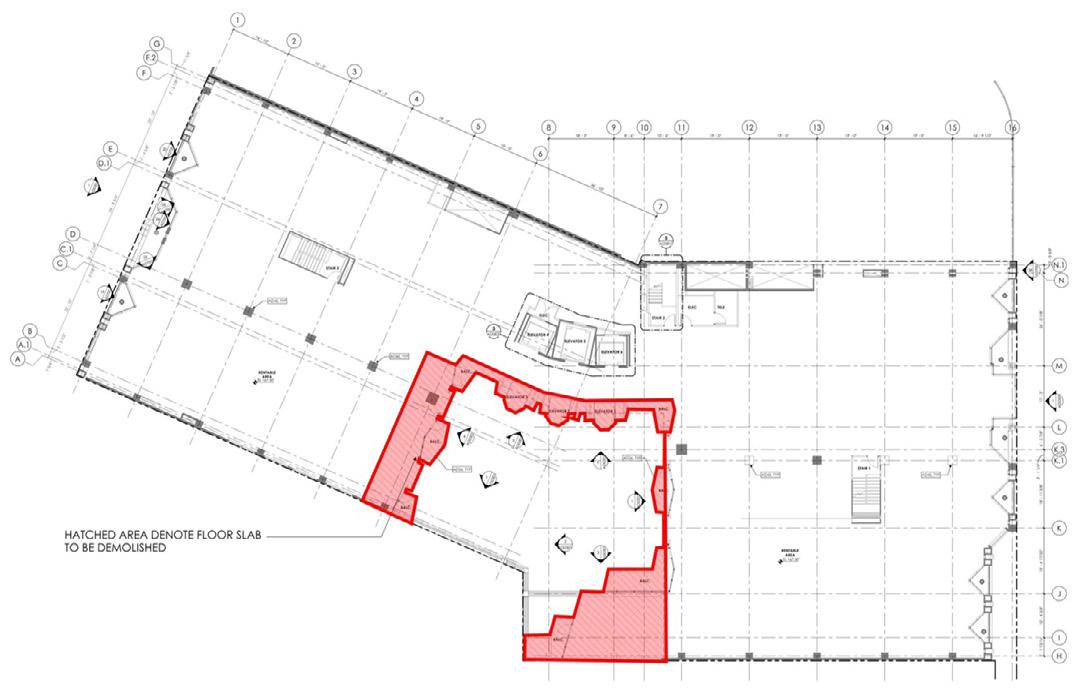

Deep office floorplates commonly utilize tensioned slabs that complicate the core drilling required for residential plumbing and ventilating. Conversions inevitably lead to the addition of residential unit balconies—projected or recessed. In addition to slab penetrations, elevator and pipe chases, egress stairs, and deep core configurations must be investigated.

“Older buildings often benefit from centralized locations and smaller, more desirable floorplates and conventional window openings.

When using existing shafts to comply with code regulations, shaft sizes must be confirmed to accommodate new riser separations between ducts. Water and sewage service, parking allotments, and obsolete equipment are additional assessments for consideration.

Structural engineers should understand existing slab conditions, assess the condition of conventional rebar, and consider any structural strengthening that may be required for additional roof loading from future amenity spaces or

a rooftop pool. In addition, sustainable features and stormwater management strategies introduce green roofs, bioretention, or deep planters, adding structural loads. If the existing building is fortunate to be below the zoning’s allowable height, mass timber construction can be a light weight and aesthetically pleasing structural system suitable for this. Other structural investigations can advise on floor leveling, edge slab conditions for new facades, and balcony feasibility.

Building Core

Large-floorplate office buildings, from the 1980s onward, have additional concerns for conversion value. These glass box era buildings, with deep core-to-perimeter wall dimensions, result in awkward, unconventional layouts. Deep cores are more difficult to program, even with some unit amenities requiring less daylight, like mudrooms and storage. Potential conflicts include dimensionally deep units with limited light compared to typical high-rise apartments.

Windowless bedrooms may be permitted within some local building codes, but undesirable apartment configurations will struggle to achieve rents or sales value that owners need to make a residential conversion feasible.

Existing core walls in these buildings tend not to be moved and stairs and elevators need to be assessed to determine if they can be reused or modified in a new residential configuration. The number of elevators needed in an office building is often greater than for residential use, so repurposing shafts for new trash chutes and mechanical or electrical risers may be a valuable trade-off. Deep floorplates can often be partially demolished to create centralized courtyards or building wings which can infuse more natural light into the units.

Mechanical Systems

A new system is often the most efficient choice, but refurbishing adequate equipment is faster and less disruptive. The penthouse was commonly utilized for mechanical systems, but many developers recognize the attractiveness of rooftop amenities. A creative solution is required to balance the needs to maximize amenities and provide sufficient area for mechanical equipment. Vertical risers will be one challenge. Unit ventilation and outside air considerations may depend on whether a central HVAC system or individual unit systems are used. Meeting energy codes with older, existing facades can be challenging.

Technological advancement of glazing systems has increased the thermal efficiency requirements for building envelopes, meaning outdated curtain walls often need replacement to comply with today’s building codes. In some jurisdictions, residential buildings require operable windows for fresh air, green code consideration, and wellness of the occupants.

Environmental Considerations

Most of the buildings built in the second half of the 20th Century were designed with little regard to energy use or environmental impact. Awareness of carbon emissions, pollution, and environmental performance are largely absent in that design. Buildings were not designed to optimize energy efficiency. Older buildings with inefficient design, controls, deferred maintenance, and outdated equipment waste billions of dollars in energy costs. Owners, investors, government officials, and designers understand that energy efficiency is good for the environment. Improved building performance through smart design and updated technologies can enable reduced waste and potential profit.

A sustainable way to add housing is by converting existing office buildings. Adaptive reuse projects are green to the core. An existing building reduces carbon by reusing concrete or recycling steel. Mass timber is also being considered for additional structural benefits.

The building infrastructure and systems, often completely new, become high-efficiency systems with modern appliances. Ventless dryers are one example of eliminating penetration. The conversion design is often greener, more efficient, or advantageously recycles large structures.

Viability of Conversions

While conversions can be an effective solution to rebalance vacant office space, not all conversions succeed. Developers, designers, and city officials cannot overlook the complexity of this trend. It is not an open and easy solution. Each property needs to be evaluated on merits to determine the probability of success—even if the costs of conversion and the existing building layout make sense. Given that many of these buildings were simply not set up to be residential, architectural oversight and financial analysis is essential. That data can inform ballpark conversion costs and market rent analyses to provide pro forma underwriting. Developers should evaluate the economic tools of government support initiatives and property tax incentive programs that financially support conversion costs.

Upcoming lender-owned properties could provide fertile ground for conversions, as buying on the right basis makes it possible to convert more buildings. Favorable urban or suburban, Class C buildings present low hanging fruit for housing conversions that could be built quickly, without subsidies, but with tweaks to codes. This obviously helps inform those conversion investment decisions, understanding that potential conversions generally demand a more rigorous level of due diligence than comparable redevelopment projects. Conversions must also consider specific site conditions such as brownfield or flood plain, historic requirements, and potential beneficial zoning that could increase heights and FAR with additional floors.

Parking requirements often decrease. This potentially adds more landscape for surface lots or potential parking level space for storage or program space potentially allocated below grade. Excess parking spaces can be leased to non-residents, or the spaces could be rentable for data centers, car dealership parking, or third-party operators like a fitness center.

Political Assistance

Cities and municipalities leverage their contribution. New amendments to zoning regulations, tax incentives, and special exemptions on energy modeling, storm water management, and mechanical ventilation are considerations. Affordable housing negotiates a combination of incentives and regulations. Cities must take a more active role in promoting and incentivizing conversions to support more urban residents that potentially boost property values. The Revitalizing Downtowns Act currently under legislation by Congress—and other potential tax law changes, such as allowing 1980s office buildings to qualify for tax credits—would also be beneficial. Developers contemplating conversions have another consideration: rental, condominium, or assembling a combination of residential unit mixes. A condominium structure has less flexibility than rental apartments if the developer wants to sell the property in the future.

Final Keys to Success

It is important to engage a creative design team that understands and can manipulate existing buildings to adapt and reuse. The ability to visualize beyond existing walls, slabs, columns, and core can create an experience that is unique in comparison to any other residential project in an urban context. The development and delivery teams should be prepared for quick decision making for program, costs, and schedule. The costs of new ground-up construction can be a comparison driver to demolition, renovation, and rehabilitation of existing buildings. The quicker a building can be assessed, the more informed the team can be on the solution. This includes program verification, the reuse of elements, clashes within the existing structure,

new component additions, and early design decisions for release packages. As more conversions come to fruition, common modifications such as new footings, strengthening, transfer beams, floor leveling, and balconies can be categorically priced. Projects are evaluating financial strategies. Domestic product buying, early procurement, and open specification with strict discipline on changes all mitigate risk. Material procurement fluctuates and construction costs are leveling, yet labor shortages have continued impact. The high demand for multifamily will continue even as borrowing costs impact commercial lending. We remain optimistic about the business trends for multifamily conversions.