6 minute read

HERE

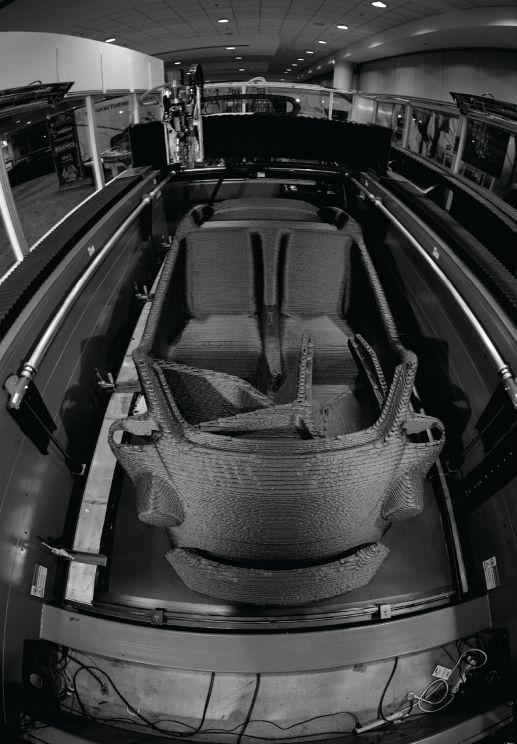

David Woessner held up a skateboard that was once a bucket of pellets, fed into a 3D printer, and manufactured, as if out of thin air. In front and to the side of him sat other examples of his company’s work: a car fender and parts of a mini-self-driving shuttle bus, all created from the touch of a button of a 3D printer. “We exist to shape the future,” said the general manager of Local Motors to the participants at the Greater Washington Board of Trade Outlook conference. “We don’t take that lightly.”

Local Motors isn’t the only one that’s living evidence that the future is here, and here in Greater Washington. Other companies are changing how industries view manufacturing, crowdsourcing, workforce trends, investment in local resources, and sustainability.

Advertisement

Local Motors is one example of such science fiction-turned-reality. It designs cars which are then produced with a 3D printer. These are no skateboards–they’re legitimate, legal driving machines.

Similarly, online education company 2U, headquartered in Landover, Maryland, is changing the way people are learning. It’s bringing students to top universities to earn graduate degrees online without having to set foot on campus.

And popular athletic wear company Under Armour is making huge strides with its sweat-wicking, performance clothing, which is already a far cry from the cotton shirts that founder Kevin Plank used to have to wear under his football jersey in high school and college. His products, ranging from athletic clothing for all sports and activities to shoes and devices, are worn by superstars and amateurs alike. Now, Un-

Oppty Box

der Armour is looking to change the face of Baltimore, too, through its real estate venture.

These companies bring with them science-fiction-turned real life, concepts that are hard to grasp even for futurists, but are already on the road, being used at work and at home, by the government and professionals. Not only that, they’ve taken up headquarters here in the Greater Washington region, plunging the area full-force into an accelerating, thrilling, brave new world of opportunities and growth.

Industry Disruptors

Woessner compared the difference between traditional car manufacturing and the simplified approach by Local Motors. “When you think about design, development, engineering, production, supply chain, value chain, marketing, service, financing, you got a pretty complex system,” Woessner said. “With our approach, we can disrupt this system.”

Woessner could have been talking about any number of companies. In his case, Local Motors’ advantage in automotive manufacturing over traditional manufacturing is its ability to simplify the process. A traditional vehicle has about 25,000 components. A car printed by Local Motors, on the other hand, consists of only 50 parts. This advantage gives the company far more flexibility to change the car’s design.

To build a traditional car, parts are sourced worldwide and assembled in a factory overseas before placed on a boat to be shipped out. A car made by Local Motors, however, is created in a smaller factory on US soil. By scale, it produces far fewer vehicles—about one to three thousand a year compared to 100,000 to 500,000 by a traditional manufacturer—but it can update and upgrade its vehicles to be locally relevant for a fraction of what it costs a traditional manufacturer to retool its factories. Woessner called this “micro-manufacturing.”

And the company’s nimbleness is faster than a traditional company. Local Motors was recruited by President Obama and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to create a reconnaissance vehicle to deliver supplies for fighters. The average defense contractor prototype usually costs several million and takes 2-3 years, Woessner explained. Local Motors delivered one in five months and under $400,000, which was even lower than DARPA’s request for six months at $500,000.

The Strati vehicle, the first 3D printed car, first took 180 hours to print, and three weeks later, Local Motors printed the same car in 44 hours. Similarly, last January, IBM Watson announced it wanted to add its question-answer computing system into a vehicle. Within five months, Local Motors was up and working with IBM, and completed it by June.

Local Motors has invested significant resources in Prince George’s County, including at National Harbor. The idea is to allow smaller businesses opportunities to compete and to enjoy the full breadth of innovative ideas, rather than just that of larger companies. “We really fo- cus on… creating local supply chains and value chains to create vast manufacturing jobs,” Woessner said.

Local Motors also leans on crowdsourcing to develop its concepts and designs. Each product is announced with a design competition, in which any number of designers and engineers around the world can submit a concept. The network votes and decides the final design.

“Our development is focused on co-creation, where we harness the power of the crowd, because we believe that oftentimes, the smartest people in the world don’t work for Local Motors,” Woessner said. Its online community consists of around 60,000 members across 140 countries, who are industrial designers, engineers, markers, manufacturers, general vehicle enthusiasts, or consumers.

Building Communities Online

Similarly, online education is rapidly changing the way universities teach and the way students learn. Now, even more students worldwide can access the best education without having to leave home, except for an occasional in-person visit or internship. Through 2U’s online education platform and partnerships, students can earn an MBA from American University, a master’s in nursing from Georgetown, a master’s in public health from George Washington University, a master’s in social work from the University of Southern California, or a master’s in information and data science from UC Berkeley, among other graduate programs around the country.

Currently, more than 21,000 students are enrolled in degree programs offered through 2U, across all 50 states and 75 countries. It’s allowed students who, in the past, were hampered by geography, family demands, disability, military, or job constraints, to earn graduate degrees. 2U has also enabled schools that have experienced drops in applications to increase its reach.

By bringing higher education to the students, rather than recruiting students to the campus, 2U also builds a global learning community around the experience. The advantage for universities is it can offer the same degree to online students as in-person students, without being confounded by space and resource limitations.

Students can also enroll across universities with any of the programs offered through 2U, which allows students to “grow their network of professional peers and study with renowned professors,” according to its website.

2U follows the philosophy: “no back row,” meaning it strives to provide every online student an up-front, personal experience in each class. Though headquartered in Landover, it has offices in New York, Denver,

Los Angeles, Chapel Hill, and Hong Kong, plus remote tech developers around the world. It also draws on aggregated information to decide what degrees and courses are most in demand and would benefit best with an online experience, such as degree conferral and job growth, online search trends, and geographic data.

Focusing on Local

While these companies are reaching high and crowdsourcing globally, they’re focused on tapping the local resources. It’s an effort to reduce global footprint and to contribute to the local community by sourcing nearby, providing jobs, and serving as a source of local pride.

In order to expand Under Armour’s accelerated growth, founder Kevin Plank went looking for more space and started a new venture into real estate. He’s planning to revolutionize the city of Baltimore by building up 235 acres of unused industrial land and space at Port Covington, of which 50 acres will be dedicated to the Under Armour campus. The space will rival Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, and will be one of the first sites people traveling north or south along the I-95 will see.

“We think that the I-95 is really a front porch of Baltimore,” said Mark Weller, president of Sagamore Development, one of Under Armour’s partners established to help develop Port Covington.

“It’s really one of the front porches of the East Coast.”

Already, it’s home to the Foundery, a networking membership which provides industrial tools and skills training, and a rye whiskey distillery in an effort to bring back one of Maryland’s biggest products as a nod to its heritage. It’s also home to City Garage, a manufacturing incubator which houses Under Armour’s Lighthouse lab center, as well as several companies that produce skateboards and watches, for example.

There are three requirements to be a part of City Garage: the company has to make a product, it has to stay in Baltimore, and it has to provide jobs in Baltimore.

And Under Armour’s own innovation sets the stage for others in Baltimore. Under Armour opened Lighthouse in City Garage, which houses a 3D printer. This year, it printed its first pair of sneaker soles for its multi-use shoe, called the Architech. 3D printing only takes 24 hours to produce and deliver soles, compared to a month with traditional manufacturing and shipping. Its soles also adapt to several activities, allowing the wearer to only need one pair of shoes instead of several (running or basketball shoes, for example).

Under Armour hopes its own initiatives will encourage other companies and start-ups to “make Baltimore better, in design and innovation across the board,” Weller said.