9 minute read

THE CO -OPERATIVE EFFECT

by JOE GUINTO

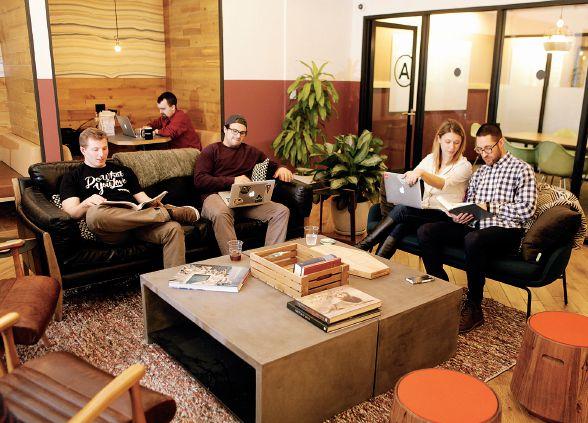

The future of work involves cold-brew coffee, a bar lined with subway tiles, a rooftop patio, and an airy lounge with its tobacco-brown leather couches. Or, at least it does inside an old Wonder Bread factory in Washington’s Shaw neighborhood that has been converted into co-working space run by WeWork.

Advertisement

Here, dozens of small companies work in a mishmash of office styles. Some operate out of large, open-plan spaces. Some work in small rooms alongside just a few people. Others drop in every day to open their laptops on shared desks. And still others use the space as if it’s a coffee shop—working there only occasionally while seated on a barstool or a lounge chair and sipping java. Free java.

Workers and small companies are drawn to WeWork because of all that flexibility, and because of the potential synergy with other companies who occupy the office, or barstool, next to them. Which is why WeWork, a booming Silicon Valley firm with a $16 billion valuation, doesn’t see itself as being in the real estate business even though it leases five million square feet of

80,000 WeWork members worldwide

8 WeWork offices in Greater Washington 60% of commercial property buyers in Washington, DC, came from overseas in 2015 95% of millennials say they would take better work-life balance and workplace mobility over a higher salary

WASHINGTON RANKS #4 as a destination for foreign capital investments in commercial real estate

Traffic Relief

More people. More cars. Same number of roads.

How do transportation planners working on one of the nation’s most congested traffic corridors move all those people in all those cars more quickly than they do now? The answer in Virginia: Flexible lanes.

“We asked: How can we get more throughput?” said Aubrey Layne, secretary of transportation in Virginia. “One answer was high-occupancy lanes.”

The first were completed in 2014 on I-95 from Garrisonville Rd. in Stafford County to just north of Edsall Rd. on I-395 in Fairfax County. An extension to that section is now getting underway, and another 10 miles of toll lanes are expected to be added on I-95 south of Fredericksburg.

On I-66, for 22 miles outside the Beltway to University Blvd., five lanes of traffic will flow in each direction by 2022. Three will be regular lanes and two will be HOV or HOT. For vehicles with less than three passengers, using a HOT lane will require a toll tag and varying toll rates will apply depending on how much traffic is on the road. The more traffic, the higher the toll.

“When we finish our current work,” Layne said, “there will be about 85 miles of high-occupancy vehicle or high-occupancy toll lanes on those roads—depending on the time of day—that people can use seamlessly.” space to 50,000 individuals and businesses in 25 cities worldwide. “We’re in the business of making people happy and successful,” says 40-year-old co-founder Miguel McKelvey. “Our spaces are obviously a big part of that, but we think we offer something more, holistically, in terms of what it means to work in the world today.”

A Collaborative Effort

And what does it mean to work in the world today? In one word: Collaboration. Companies large and small are looking for ways to foster better collaboration between workers who sit next to each other as well as those who may work in different departments in different places around the world. That’s partly why 70 percent of office workers now work in “openplan” spaces, according to the International Facility Management Association.

It’s also why, even as the federal Gen- eral Services Administration reports that government offices in Washington are shrinking, co-working space in the area is growing. “Co-working has taken up about half a billion square feet of space in the DC metro area this year alone,” said Revathi Greenwood, director of research and analysis for CBRE Group Inc., at the Outlook conference. “And this is a totally new sector. In 2015, co-working space was just 150,000 square feet.”

Top: Kitchen in WeWork’s DCChinatown space.

Bottom: The recentlyopened WeWorkMetropolitan Square above Old Ebbitt’s Grill covers more than 100,000 square feet over two floors.

In the District, WeWork has six different co-working spaces—in the booming 14th Street corridor, in the rapidly redeveloping Shaw neighborhood, in Dupont Circle, in Chinatown, on K Street amid the offices of numerous lobbying firms, and directly across the street from the US Treasury Department. The last one sits upstairs from the famed Old Ebbitt Grill, in a sprawling 100,000 square feet of space housing about 2,000 tenants.

Cove, another co-working space, is also growing rapidly in the area. Cove has offices in Dupont Circle, Chinatown, and on Capitol Hill. Cove’s offices are not as elaborate as many of the WeWork sites, which offer private, permanent spaces with doors and dedicated phone lines. But Cove members do get a desk, access to printers, fax machines, and meeting rooms, as well as free coffee.

Even Regus PLC, a long established office rental company, has shifted into the co-working space. Regus’ clients in Washington and elsewhere can now buy packages that allow them to drop in on a desk as needed or to reserve their own desk for more frequent visits to a specific site.

The Mobile Workforce

All of that is good news for small firms looking for a better place to work than the corner coffee shop while also hoping to connect with other local businesses and spur growth. But there’s a catch to the density offered by co-working spaces like WeWork. With co-working spaces mainly opening in the center of the District, and with rents and home prices rapidly rising there and in other parts of the city, plenty of people who use co-working spaces here—many of them millennials—face long commutes to work. And that commute has become more complicated of late with service disruptions related to Metro’s ongoing SafeTrack rebuilding project and with road projects happening on some of the area’s most congested highways.

“The population in this area continues to grow,” said Aubrey Layne, secretary of transportation in Virginia. “The number of people in cars continues to grow. Even though there are different options today, like biking, bus, and Metro, this area’s roads continue to get more congested.”

But even though the ride to work may not become more pleasant for a while, the work environment can be—at least for companies who are successfully embracing the collaborative ethos of co-working, which is becoming more valued by the millennials who now make up the majority of the workforce.

“Millenials have different expectations of work-life balance and work locations,” said Molly Bauch, technology strategy manager at Accenture in Washington, at the Outlook conference. “They want more rolebased work and project-based work. They expect to be able to work on mobile apps. They expect to have flexible work environments.” Not only that, she said, about 95 percent of millennials want that flexibility and mobility over a higher salary.

Bauch said that presents a challenge for business leaders. “We have a mobile, young workforce in Washington,” she said. “So leaders today have to work in a highly networked, collaborative, and ever-experimenting environment. They need to orchestrate many different skills across many different teams—in very much a project based world—to accomplish their new business goals.”

METRO’S TRACK TO IMPROVEMENT

The bumpy ride for the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority isn’t over yet. A series of service disruptions across the Metro system and fires inside of underground stations prompted an unprecedented one-day shutdown of all stations in 2016. A yearlong repair project, called SafeTrack, has followed those incidents, resulting in a rolling series of station closures and line repairs that will continue into 2017.

“The next two years will be difficult,” said Metro general manager Paul J. Wiedefeld at the Outlook conference. “We have a huge budget hole coming into 2018 and we have a lot of work to do before then to get the system reliable.

“But,” he added, “the needle is moving.” lators—coverings designed to keep fires on the rails at bay—have been replaced with more modern, safer insulators during the months since SafeTrack began.

But as the system slowly gets safer and more reliable, it is paying a price for disruptions caused by the rebuilding project. Ridership has fallen by 10 percent in some months last year over the same month in the prior year. One report suggests that ridership is, at times, hitting 10-year lows.

ON THE RIGHT TRACK Metro has been rolling out the Safetrack program to address repairs and system reliability.

Crossties, fasteners, and insulators are moving, too. All of those important cogs in the Metro machine have been replaced by the thousands during SafeTrack. More than 3,000 old insu-

Wiedefeld said that when SafeTrack is concluded, he wants to win those riders back by offering more reliable, more extensive service—including the expansion to Metro’s Silver Line and the recently approved Purple Line. And building a bigger, better Metro, he said, is critical to the area’s long term economic development. “The Metro system,” Wiedefeld said, “is one of the biggest tools in our toolbox in terms of global competition.”

UNION STATION’S BACK

In its first century of operation, Union Station connected Washington, DC, to the nation. Now, as part of a “Second Century Plan,” Union Station’s overseers hope to better connect the station to Washington, DC.

Union Station Redevelopment Corp. is already underway with its $10 billion Second Century Plan. It calls for building a massive deck over the area behind the station where train tracks cut blocks out of the city’s street grid when Union Station opened in 1908.

The deck will reconnect those blocks, offering public spaces and three million square feet of new space for offices, hotels, and residences. In the center of the deck, a glass-topped train shed will be built, descend seven stories from the deck level to make room for new, wider, train tracks, new train concourses, and a new area where buses and taxis can drop off and pick up passengers.

Beverly Swaim-Staley, CEO of the Union Station Redevelopment Corp., called the ambitious plan, which is still in the fundraising stage, a “mega project.” It may not get fully underway until 2020. In the meantime, big improvements will be made to the existing station, including widening the current Amtrak concourses—where 37 million passengers arrive and depart each year— and creating a larger entryway for the Metro stop at Union Station—the busiest station in Metro’s system. Those projects should be completed by 2019. Another proposal includes an adjoining hotel, in which the lobby will be housed in the former B. Smith’s restaurant, also the site of the ornate original presidential waiting room.

NEW AND IMPROVED

A proposed redesign for Union Station includes widening the Amtrak and commuter train concourse.

Finding the Right Blend

That orchestration can be as challenging as the morning commute. Many companies are struggling to develop the right kind of collaborative environments, ones that foster creative co-working without sacrificing workers’ ability to concentrate on their daily tasks. At WeWork and other co-working sites, the idea is not to force collaboration on any of the member tenants, but to create a range of environments where members can do their work.

“Some people like quiet and separation,” McKelvey says, who has an architecture degree and is chief creative officer for WeWork. “Some people love to be surrounded by activity and people. Hopefully we can find a way to serve all of those people and help make it easier for them to follow their passion.”

WeWork also tries to offer multiple ways for companies to connect even if they have disparate business operations—in Washington, a taco-making company has WeWork space nearby a brand-development and graphic design firm. That’s accomplished through a LinkedIn-style online network where members can pose questions to each other and list job openings. It’s also accomplished through a continual series of optional events at its offices. Those events may have something to do with business, or they may not. A JavaScript tips session after work on one day may give way to an ice cream social in the shared kitchen at midday on another or to “Dr. Ruby’s Easy Vegan Cooking Class” on yet another day.

“We’re trying to authentically connect with our communities,” says chief creative office McKelvey, who has an architecture degree. “At WeWork, you meet people with shared experiences. You even get emotional support, where you can find other people who understand the challenges of running a business. You have the ability to bounce stuff off of them.”

It may feel a little touchy-feely, but, then, that makes sense, given WeWork’s roots. McKelvey spent part of his childhood on a collective headed by five single mothers in Oregon. His Israeli-born co-founder spent part of his childhood on a kibbutz in Israel.

But even some of Washington’s most traditional employers may be able to adopt one of WeWork’s core values—proving meaningful work to their employees. “At a fundamental level, what a lot of us want is to find meaning in our work and feel like our time isn’t being wasted,” McKelvey says. “That can be a pretty ephemeral thing. But I think you really end up feeling the power of it when you’re in our spaces for a while.”