DAYtrip

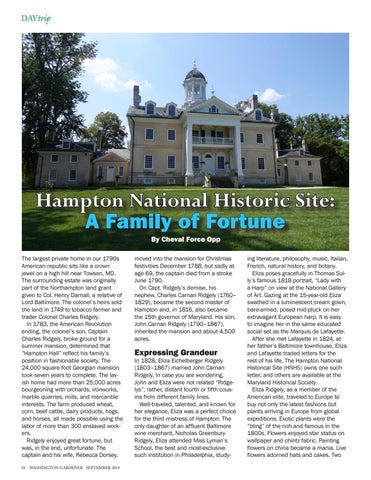

Hampton National Historic Site: A Family of Fortune By Cheval Force Opp

The largest private home in our 1790s American republic sits like a crown jewel on a high hill near Towson, MD. The surrounding estate was originally part of the Northampton land grant given to Col. Henry Darnall, a relative of Lord Baltimore. The colonel’s heirs sold the land in 1749 to tobacco farmer and trader Colonel Charles Ridgely. In 1783, the American Revolution ending, the colonel’s son, Captain Charles Ridgely, broke ground for a summer mansion, determined that “Hampton Hall” reflect his family’s position in fashionable society. The 24,000 square foot Georgian mansion took seven years to complete. The lavish home had more than 25,000 acres bourgeoning with orchards, ironworks, marble quarries, mills, and mercantile interests. The farm produced wheat, corn, beef cattle, dairy products, hogs, and horses, all made possible using the labor of more than 300 enslaved workers. Ridgely enjoyed great fortune, but was, in the end, unfortunate. The captain and his wife, Rebecca Dorsey, 18

WASHINGTON GARDENER SEPTEMBER 2019

moved into the mansion for Christmas festivities December 1788, but sadly at age 69, the captain died from a stroke June 1790. On Capt. Ridgely’s demise, his nephew, Charles Carnan Ridgely (1760– 1829), became the second master of Hampton and, in 1816, also became the 15th governor of Maryland. His son, John Carnan Ridgely (1790–1867), inherited the mansion and about 4,500 acres.

Expressing Grandeur

In 1828, Eliza Eichelberger Ridgely (1803–1867) married John Carnan Ridgely. In case you are wondering, John and Eliza were not related “Ridgelys”; rather, distant fourth or fifth cousins from different family lines. Well-traveled, talented, and known for her elegance, Eliza was a perfect choice for the third mistress of Hampton. The only daughter of an affluent Baltimore wine merchant, Nicholas Greenbury Ridgely, Eliza attended Miss Lyman’s School, the best and most-exclusive such institution in Philadelphia, study-

ing literature, philosophy, music, Italian, French, natural history, and botany. Eliza poses gracefully in Thomas Sully’s famous 1818 portrait, “Lady with a Harp” on view at the National Gallery of Art. Gazing at the 15-year-old Eliza swathed in a luminescent cream gown, bare-armed, posed mid-pluck on her extravagant European harp, it is easy to imagine her in the same educated social set as the Marquis de Lafayette. After she met Lafayette in 1824, at her father’s Baltimore townhouse, Eliza and Lafayette traded letters for the rest of his life. The Hampton National Historical Site (HNHS) owns one such letter, and others are available at the Maryland Historical Society. Eliza Ridgely, as a member of the American elite, traveled to Europe to buy not only the latest fashions but plants arriving in Europe from global expeditions. Exotic plants were the “bling” of the rich and famous in the 1800s. Flowers enjoyed star status on wallpaper and chintz fabric. Painting flowers on china became a mania. Live flowers adorned hats and cakes. Two