21 minute read

Literacy

by Brett Bishop, Anthony Hill, and Kerry Purcell

Advertisement

Mr. Bishop is a Lead Senior Consultant with Focused Schools and a member of the Leadership Team. He is an expert facilitator of professional development, executive coach, and a technical assistance provider to school and district leaders across the country. Brett has provided support to hundreds of school leadership teams, school administration, and district office leaders, as they work to develop strong systems and structures that get results. Brett began his education career in the Springfield, MA Public Schools. During twelve years in the district, Brett served as a teacher and assistant principal before becoming the principal of the East Street School in Ludlow, MA. Under his leadership, the school made significant gains in student achievement, was removed from In Need of Improvement status, and the district was one of only two in the state to move out of Corrective Action. The school was also recognized by the Massachusetts Legislature for outstanding work in creating trauma-sensitive learning environments. Brett recently partnered with Kerry Purcell, co-author of their newly released book, Focused Schools: Transforming Teaching and Learning for Every Student, Every Day.

Dr. Hill is a Senior Consultant with Focused Schools. His expert facilitation and coaching skills empower school and district leaders to inspire, motivate, and create a supportive environment for children, adolescents, and their families to attain academic success in a rigorous and safe learning environment. Tony served as a school social worker, school adjustment counselor, assistant principal, and principal in Springfield, MA, with a focus on reaching and teaching all students by leading for results using both influence and authority. Tony also serves as an Associate Professor in the School of Social Work at Springfield College in Springfield, MA. Tony has traveled the country and is highly sought after to serve as a keynote speaker on topics including the multigenerational workforce, diversity and inclusion, trauma sensitive education, and social advocacy. Ms. Purcell is a Senior Executive and Partner with Focused Schools and an expert leader, developer of curriculum, facilitator of professional development, executive coach, and technical assistance provider to school and district leaders across the country. Kerry has provided support to hundreds of school leadership teams, district office leaders, and instructional coaches as they work to develop strong systems and structures that get results. Prior to leading Focused Schools, Kerry served for eight years as a Senior Consultant with the company. Before coming to Focused Schools, Kerry was a teacher and principal for Springfield Public Schools in Illinois. As the principal of Harvard Park School, the school was removed from the state watch list due to rapid gains in student achievement. Harvard Park was also one of two schools selected to be featured in the PBS full-length documentary, The Principal Story. Funded by the Wallace Foundation, this documentary explores the complex role of the principal and the impact that this role plays in the quest for lasting improvement. Kerry has been asked to keynote national conferences, including the ASCD conference; served as an adjunct professor for Concordia University; and has co-authored the book, Focused Schools: Transforming Teaching and Learning for Every Student, Every Day.

ffective teaching and learning for all students in our schools will determine the future of this country. Schools need teachers who are equipped to effectively teach literacy and who genuinely care about academic success while simultaneously nurturing the social and emotional well-being of all

Estudents. And those teachers need administrators who are leaders of literacy. Douglas Reeves states, “literacy is the top priority of equity and excellence in schools” (Reeves, 2020, p. 41). It is vital to have strategies developed around literacy, including phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency,

vocabulary/language development, comprehendsion, and getting children excited about learning. In addition, meaningful, caring relationships between teachers and school administrators with students

can play an essential role in maintaining a positive educational experience for students. All students deserve an adequate education designed to deliver on the promise to prepare and equip them to choose to be socially mobile assets to the global economy, free from any stereotypes associated with their socioeconomic class or zip code. This article details the actual experiences of how one principal in New Bedford Public Schools (MA) partnered with her Schoolwide Instructional Leadership Team (SILT) and the entire staff to successfully turn her school around through promoting and championing literacy for all students, including the most at-risk and vulnerable learners.

One School’s Story

James B. Congdon Elementary School is located in the south end of New Bedford, Massachusetts, and serves approximately 300 students in kindergarten through grade five. The school, built in 1907, sits in a densely clustered neighborhood, with roads narrow enough to present challenges for passage in times of snow in this coastal New England city. More than 85% of Congdon students are designated as “high needs,” and over 50% are identified as “first language other than English” by the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE). For more detailed demographic information about Congdon, visit https://bit.ly/3dz4gSc. In any typical year, approximately one-third of all students reached the advanced or proficient level on standardized testing in both Math and ELA. In July of 2015, Ms. Darcie Aungst was announced as the new principal after serving as a middle school assistant principal in New Bedford Public Schools (NBPS). It was her first principalship, and she was excited for the opportunity to continue to serve students. The school building was old and showing wear, but the staff was dedicated and welcomed her arrival. They were hoping that her promises to stay would actually come true. The remarkable progress that occurred at Congdon Elementary over the next four years has received significant attention and acclaim, including being recognized two years in a row by DESE as a “School of Recognition.” Congdon Elementary was highlighted as one of six schools in Massachusetts receiving commendations in all three areas of high achievement, high growth, and exceptional performance relative to improvement targets. (See Figure 1.) To read more about the Congdon success go to https://bit.ly/3alIU8F. In the following excerpts from the interview, Principal Aungst shares the journey that she and her team led to improve teaching and learning for all students, no exceptions.

Figure 1

100

50

James B. Congdon Elememtary School

32 34 31 47 55 54 60 73 81 79 81 94

2015-16 2016-17 2017-18

ELA Math Science 2018-19

*Note that the language of this text has been edited in some places to allow clarity for the reader in transition from the spoken to the written word.

Interview With Darcie Aungst, Principal of James B. Congdon Elementary School

Interviewer: Can you talk about how you included teachers in leading the improvement efforts? Principal Aungst: We first had to establish the SILT. I made sure that I had representatives from each grade level, special education, ESL, and specialists. Schoolwide representation would ensure that implementation of evidence-based practices would be implemented across the entire school. SILT met regularly and we had the system set up Instructional Leadership Team to look at data. In the beginning, we picked one or two data The leaders at Congdon meet regularly and focused only on improving daily teaching points or standards within the data. If it was showing up in every and learning. They refer to this team as grade level, we knew it was a systemic problem. “SILT: Schoolwide Instructional Leadership Team.” Made up of a cross-section of people Over time, we learned to look at data together. Eventually representing the full staff, they use data to the teachers lead the conversations and the analysis of the data. drive their decisions on important levers like professional development planning, I started giving them time with the data ahead of the meeting so internal account-ability action, and schoolwide com-munication. Darcie attends that they used meeting time to talk about what they notice and every meeting of this team but sees one of what they wondered. Those conversations started to get really her roles as ensuring that all voices are heard. This team takes a collaborative rich, which helped us to discover through lines between the approach to making many of the most grades. This led to picking standards to attack across the school. important decisions regarding instruction at Congdon. For instance, vocabulary was one that was just always killing us. In my first year, all students were in the red [below grade level proficiency]. I remember having the discussion with you [Focused Schools], “How do you even know where to start when you are below the state average in every single standard?” We were. There was not one standard where we were even close to the

state average. I just remember, and this will be burned in my head forever, that in most grades’ vocabulary acquisition was 36% below the state. At first, the staffs’ reflex was to say, “Well, yes, because they bussed in all the ELLs, of course our vocabulary standards are down.” My response was, “That’s a place we can start then. Let’s really attack that.” As a leader, I realized that at that moment I had to let the teachers grapple with the data. After the grappling, we then spent the majority of our SLT time asking ourselves, “What are we going to do about it?” Interviewer: Yeah. Well, what is it that they say in education? We are really good at admiring the problem. Principal Aungst: Yes, that is so. I don’t know why that is a natural Darcie spoke to an example of tendency for people. We just didn’t go there. We decided to take the how the teachers used demonstrated student needs in approach, “We are committed to fixing this; we believe our kids can do the learning data as the center of this; and we believe that if we accelerate vocabulary development, that is collaborative discussions that were initially challenging, but a really strong lever for overall reading comprehension.” And, it’s funny, critical, in their ultimate pursuit we’re doing some LETR training now, and that training is around building of collective commitments to instruction. background knowledge and vocabulary acquisition. Those are the two areas that really are most important for overall Impact of Accountable Talk on Student Learning reading comprehension, plus decoding, To hold people accountable, Principal Aungst used obviously. But, when you get into the learning walks to check for fidelity of implementation. Her comprehension piece, those two really need to learning walks, from the start, focused on the implementation of their SWEBIP. Growth-producing feedback was provided. be going full tilt.

Teaching and learning began to change. In our conversation, Interviewer: What process did you and your

Principal Aungst recalled a time when she started to see team use to decide what parts of daily students owning their learning: instruction would be the same across all I would see accountable talk a lot in ELA at first, and now classrooms?

I see it everywhere, everywhere, everywhere, everywhere. If you came and talked to a student in the hall, they would Principal Aungst: Just like I mentioned answer your question, “Hi, it’s nice to meet you, sir. I’m before about collaboration, that started with

Joseph.” In fact, I was in a class the other day where there was the data, so we looked at the literacy standards. a little girl who came seven weeks ago from Guatemala. The teacher asked a question about grazing as the vocabulary As a SILT team, we then started the process of word. The student raised her hand, and she said, “I know that working with all the teachers. I was the the word grazing means ‘to eat,’ and the whole class cheered! facilitator for this. This all came from teachers.

It was actually during a learning walk. One of the little first graders noticed one of the learning walk people looking I would give a little bit of homework around, confused as to why they were cheering. So, he said, “We're “Look at this data. Come back with what you cheering for her because she's just learning English, and that was her first complete sentence.” notice, what you wonder, and what you want to do about it.” Then we would have the

meeting and say, “Okay, what are we going to do about it?” The next homework assignment was for everybody to research evidence-based practices that dealt with the identified standard. At the next SILT meeting, the teachers would come back with potential practices and start great discussions. We then boiled it down to one or two schoolwide evidence-based practices (SWEBIPs). But I wanted to make sure, number one, the commitment was that these SWEBIPs would be schoolwide. We didn’t commit to anything that could not be done in every class, including specialists, special education, ESL, math, and ELA.

After the practices were selected, the SILT designed targeted professional development. We started with one SWEBIP - accountable talk. During professional development we modeled what we wanted them to do with students using accountable talk and language. Grade-level groups came up with their own commitments and expectations for what accountable talk would look like. Anchor charts were then developed and were used in every classroom.

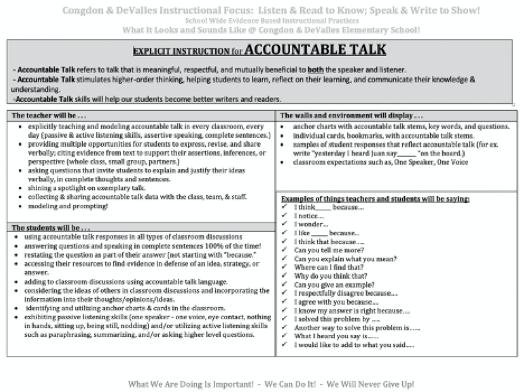

Figure 2: One-page Best Practice Definition Documents from James B. Congdon Elementary School, New Bedford Public Schools (MA)

During early implementation, I would notice on my learning walks that everyone had the exact same anchor chart. However, some anchor charts had cobwebs and dust in the corner as if they had never been used. Why? The teachers did not have ownership over the SWEBIP. I brought this data to the next professional development meeting to discuss. I asked for volunteers to hold the meetings in their classroom so that we could collectively see how the anchor charts were used and what they could take away from these observations. We also provided resources. In other words, we equipped our teachers with the appropriate tools and resources.

Interviewer: Are you saying that you had bounds, and within those bounds, you gave teachers some autonomy to make choices that were good for their students? Principal Aungst: Exactly. What started happening was that teachers were changing the way they taught because the conversations and decisions were not coming from me. They were coming from the SILT. To this day, I still notice teachers trying new things.

I also built a lot of psychological safety for the staff. I would consistently say, “I would rather have you try this and fail miserably than have your students not talking and thinking in complete thoughts and sentences. So, don’t worry if your class gets out of control a little bit.” We had a little bit of that old school, “If I let them talk, I'll never get them silent again.” I had to alleviate fears by saying, “It’s okay if you fail. I would just be so happy to see you fail because you were trying something new.” Things were changing!

I also made a commitment to them that I was going to be there, and that I would not throw all this hard work out the next year. I promised that this would be something that we build upon and use every single year. Fast forward to now and you will see that accountable talk and academic discourse are everywhere. Interviewer: What would you say you did to both sustain yourself as a leader and also the teachers and your team? How did you and your team keep the main thing the main thing?

Evidence-Based Instructional Practices

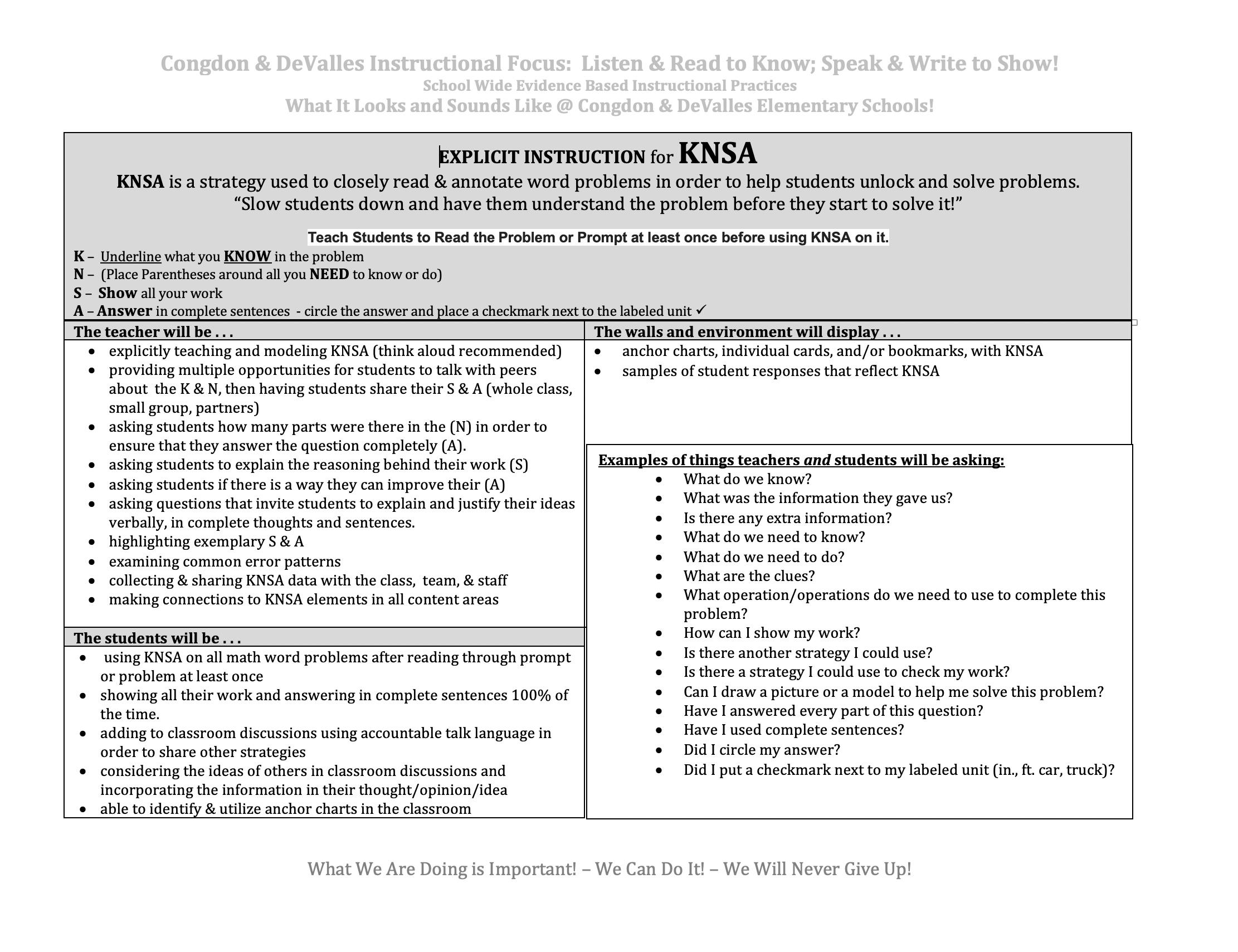

Darcie and her team lead their staff in identifying and implementing a narrow set of evidence-based instructional practices (you hear her refer to them in the interview as, SWEBIP for Schoolwide Evidence-Based Instructional Practices). Their goal was to use student learning to come to collective agreements on what parts of the instructional day will be the same across all classrooms, content areas, and grade levels. In an effort to provide clarity regarding their expectations for how these would be implemented, they created one-page definition documents for each of these practices that summarized their research and subsequent meetings with the staff. These documents are included below. (See Figures 2, 3, and 4)

Data Is Just a Number Unless We Do Something With It We used all kinds of data. I would say to the staff after an informal walk, something like, “The data showed that we had 33 percent student talk and 67 percent teacher talk. We can do better than that. -Darcie Aungst.

Figure 3. One-page Best Practice Definition Documents from James B. Congdon Elementary School, New Bedford Public Schools (MA)

Principal Aungst: The “one-pagers” [one-page description of what good work looks like related to each; see Figures 2 and 3 ) were helpful. Also helpful was our schoolwide approach to marketing our SWEBIPs. We talked about our SWEBIPs on morning announcements. We would give shout-outs when we heard the SWEBIPs being used. We would re-emphasize them. I provided formal feedback, both positive and growthproducing feedback, related to the implementation of the SWEBIPs. We made sure the practices were incorporated in all subjects. Simply put, we committed. Interviewer: Could you share the challenges you and your team considered when choosing evidence-based instructional practices, and how the number of English Language Learners shaped your decisions? Principal Aungst: Yes, absolutely. I was thinking that the reason we picked accountable talk and academic discourse is because so many of our students were struggling. I will never forget the number: 33 percent of my school was a Level One English Learner. It was a strange dynamic. Since then, I have begged the district

to keep the students with us from kindergarten through grade five. The thing that really worked with our SILT, and then again in PD, was that I was really honest about the

Instructional Focus

fact that I needed to learn a lot about the best approaches to accelerating English acquisition for ELLs. I had real empathy for the Facing student learning results that teachers. I remember saying, “You must be so worried and afraid of were consistently unacceptable, the staff at Congdon decided that they were failure and what to do when a student walks in with not even enough trying to do too many things, and were English to say, ‘Hello, how are you?’ Right? That must be what you not getting good at any of them, think about during guided reading time. This must be what you because they were spread too thin. The leadership team led the staff in a consider during small-group instruction.” In other words, we had to protocol designed to use learning data focus on this subgroup. to identify an instructional focus to

And so, I said, “We need to find out together what the best address the most central and pressing student needs. In the interview, practices are.” I think when the leader has empathy for what’s going Principal Aungst refers to the “kidon, they’re so open to say, “Yes, we need help.” As a leader, you have friendly” version of this focus, “Listen to intentionally create that. Because otherwise, I think that's where and Read to Know, Speak and Write to Show.” the defensive reactions like, “It’s the kids,” or “What am I supposed to do?” or “They don’t speak any English,” creep in.

So, together we worked a lot on explicit teaching and listening for things. We focused on using readalouds. We helped students find details in the text. Then the speaking came with accountable talk and academic discourse. This led to the development of our schoolwide instructional focus: “Listen and Read to Know, Speak and Write to Show.”

We learned speaking is not that different from writing. We really made those connections and committed to, “If we spend time, as scary as it is, developing listening and speaking, then the reading and writing will come.” There just has to be so much less teacher talk and less direct instruction and more time for kids to listen and speak. Interviewer: Is there anything that you would suggest to someone who’s not only leading a school to sustain themselves as a principal, but also to sustain the other leaders and teachers in terms of their “emotional gas tank”? What helped you along the way? Principal Aungst: You guys really gave me leadership.

I think if I am talking to other principals who are starting out or who are thrown into a different situation than they are used to, I would say, “It is okay to put other things completely on your back burner and to focus on a few best practices to drive improvement with your instructional focus. That is key and has such a big impact.” Then, you just stick with your choices. Go deep with those practices and commit schoolwide. Align your professional development, observational feedback, and topics for SILT to those practices. I think

when you give yourself permission to do a few things really well instead of trying to fix every red data point all at once, you’ll be amazed how those data points move. Interviewer: Are there any lessons that you’ve learned in terms of the idea of where explicit instruction and guided practice are concerned? Are there any lessons you’ve learned along those lines? Principal Aungst: I would say to keep up with the science of reading. As a principal, keep yourself current and informed. Know your students and do what’s right for them. I know this is going to sound ridiculous but one of the most important things for reading is to make sure kids have reading materials in front of them. Students are never going to learn to read if the teacher reads all of the time. They need text in front of them. Even when the teacher is reading, students need text in front of them. They need exposure to grade-level text, and they need scaffolded support around that text. Worksheets never taught anybody how to read. I think a multisensory approach to teaching reading really is phenomenal. That approach has helped our ELLs. Interviewer: Gosh, what an incredible, amazing story your school has to tell. And I am just so happy for you, Darcie, and you’ve done so much to help those kids. And you're such a hero in that district. It’s just an absolute privilege to talk to you about it.

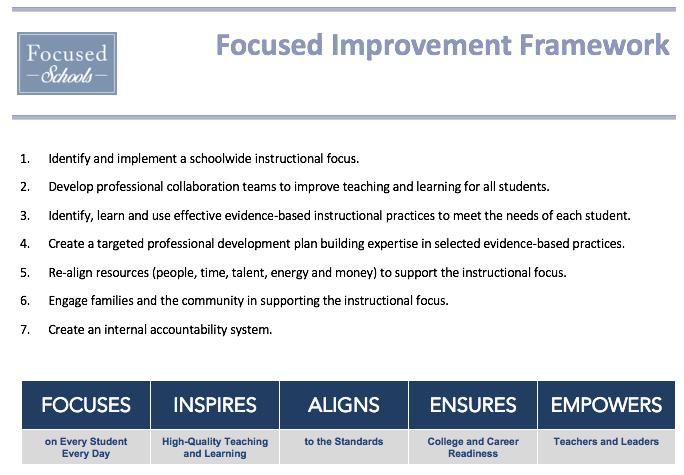

Figure 4.: Focused Schools Framework

Principal Aungst: Yeah, you know, I could talk about my school all day. Interviewer: Yes, I could listen to it all day. Are there any other lessons you have learned? Principal Aungst: Continuous learning for teachers and leaders is important. Using data is important. It has helped us to see the great news, as well as where students struggle. By looking at data, we’ve found we have had an impact. And by using the data, you can fill the gaps. Condgon students have consistently grown two and three reading grade levels in one year. It is incredible.

Equity for All: First Best Instruction

Darcie described how many students need “the core plus more.” Her teachers used diagnostic data to drive their instructional responses with significant results.

We started really using our informal phonics inventories, where you can take a struggling reader in any grade, and you give him these little phonemic awareness and phonics screeners. You can identify where the little gaps are, even by the letter, so you can “spackle the cracks” in the foundation. Once you fill the crack using a doubledose approach, even on a letter or a diphthong, they instantly jump back up. If you can fill those the gaps, their reading comp just falls into place.

About New Bedford Public Schools (MA)

Like many school districts around the globe, New Bedford Public Schools proudly states their mission statement on the district webpage. This mission statement reads: “We are committed to developing lifelong learners of strong character and confidence in their unique aspirations who can navigate life with excellence, integrity and community pride on their voyage through graduation to successful futures.” What is unique about New Bedford Public Schools, led by Superintendent Thomas Anderson, is that this mission statement is far more than just words on a website. This mission statement guides the work of every staff member across the entire school district. New Bedford Public Schools serves over 12,000 students across its 25 schools. The district leadership is committed to serving those students well. Their instructional focus serves as the centerpiece of their districtwide improvement strategy:

All New Bedford students will be:

Communicators; Collaborators; Critical Thinkers; Creative Problem Solvers; Confident Individuals; Compassionate Community members. District leadership has re-aligned their work to provide customized and immediate support based on each school’s needs. Targeted professional development for SILTs, teachers, coaches, and school administrators is intended to build capacity. District goals and strategic initiatives are identified and owned by all. SMARTe goals have been set for students and staff, allowing for monitoring of progress. In other words, it’s all hands on deck in New Bedford Public Schools.

References

Aungst, D. (2020, 3). Personal interview. Purcell,

K., Bishop, B., Leight, J. & Palumbo, J. (2019)

Focused schools: Transforming teaching and learning for every student, every day. Author. Reeves, D. (2020). Achieving equity & excellence:

Immediate results from the lessons of high poverty, high-success schools. Solution Tree Press. Schmoker, M. (2019). Embracing the power of less. Educational Leadership, 76 (6), 24-29.