7 minute read

Diagnostic Imaging in the Rise of Women's Football

Fig 1: Manchester United Football Club introduced a professional women’s team in 2018.

Dr. Eddie Craghill, Women’s Team Support Doctor at Manchester United, discusses how a deeper understanding of femalebased sporting injuries, rehabilitation and research using front-line medical imaging can help propel women’s football even further.

Advertisement

Women’s football has been growing in popularity in the UK over the past decade. It is exciting to see and helpingto inspire new generations when it comes to sporting participation, performance and equality.

Its resurgence can be charted, in part, back to the success of Team GB Women who reached the quarter nals of the London 2012 Olympics Games; to England reaching the semi- nals of UEFA Women’s Euro in 2017; and to the creation of a FA Women’s Super League ahead of the 2018-19 season. Greater television exposure of the sport is also playing its part in reaching out to encourage and grow a dedicated supporter base. This will escalate further this year with the UEFA Women’s Euro 2022 tournament to be held in England.

At Manchester United, the Women’s Professional Football team was introduced in 2018 (Fig 1), winning the FA Women’s Championship in the inaugural season. It now competes in the FA Women’s Super League, a top tier of women’s football. But behind the scenes there is also a commitment to expand female sports exercise knowledge and to gain greater awareness about gender nuances to support the rise of our female players.

Understanding & exploring gender di erences in football injuries

One of the key known areas of di erence between the male and female footballer is the nature of injury. For example, two to ten times more females than men are likely to experience an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury, which has been studied in detail over recent years1, 2, 3. ACL injuries happen suddenly and without warning and can mean being out of the game for 9-12 months. These injuries are common in football due to the frequent and instant deceleration on the pitch from cutting, pivoting or landing on one leg.

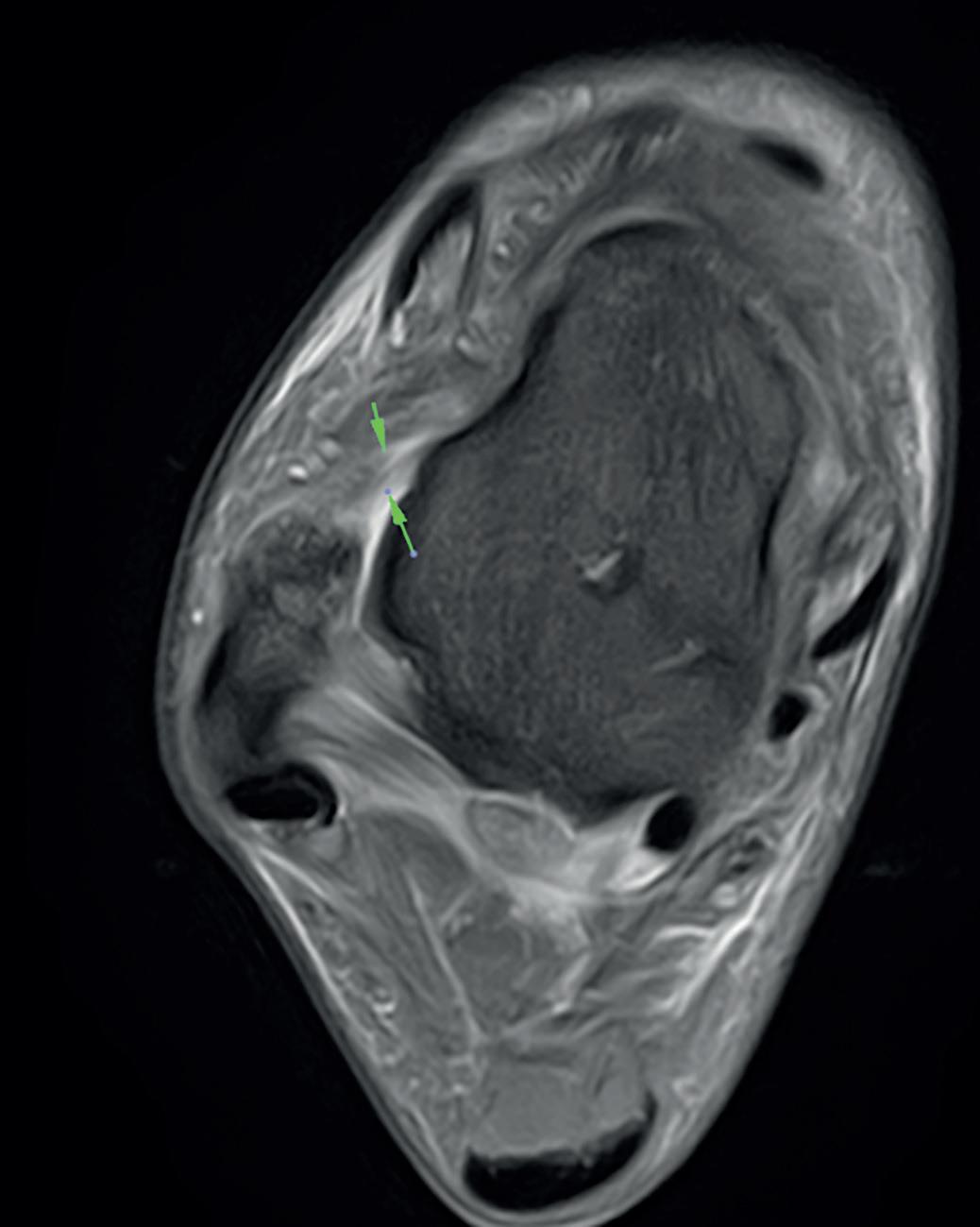

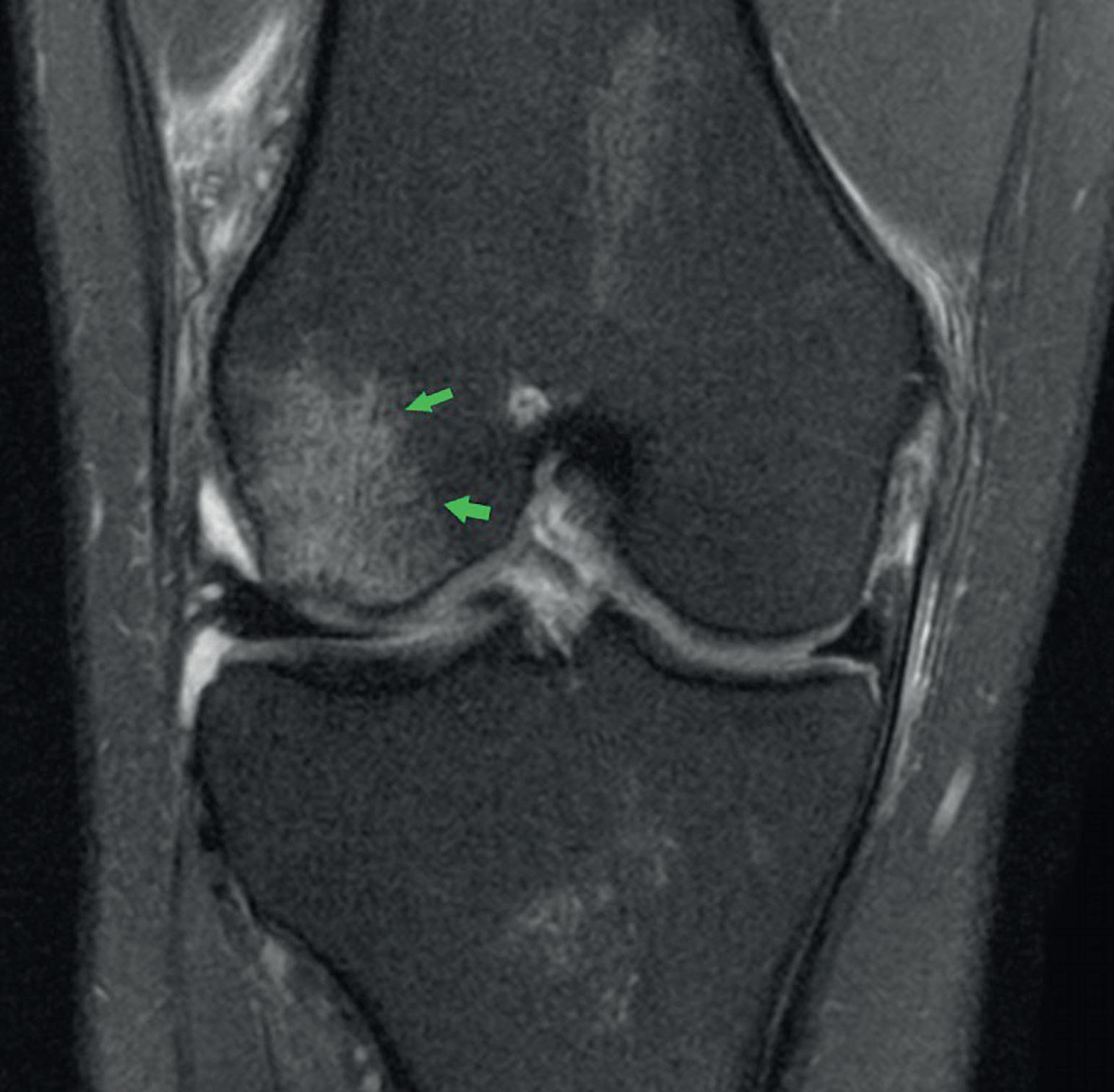

By using ultrasound, CT or MRI, we can see the extent of commonly occurring (Fig 2) or unique injury on site within our dedicated Medical Imaging Centre4 at the Manchester United Carrington Training Centre without any of the con dentiality issues of transferring a patient to a localhospital. Figure 3, for example, shows a T2 weighted image of the coronal view of the right knee showing an acute pivot shift injury with an acute lateral condylar bony contusion which is highly indicative of an associated ACL tear. The female athlete was examined using a Canon Medical Vantage Galan 3T MRI.

Top Right Fig 2: Canon Medical Vantage Galan 3T MRI acquired Axial PD Fat Supressed image of the right ankle demonstrating a grade 1/2 tear of the anterior talo bular ligament (ATFL).

Bottom Right Fig 3: Coronal PD Fat Saturated image of the right knee showing an acute pivot shift injury with an acute lateral condylar bony contusion, which is highly indicative of an associated anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear acquired using Canon Medical Vantage Galan 3T MRI.

Manchester United Women's Team in training

The known predisposition in female football players has no singular cause, but is thought to be a mixture of anatomical di erences, including: the intercondylar notch, a groove at the bottom of the femur where it meets the knee, which is larger in men than in women; increased knee valgus, the Q angle formed between the quadricep muscles and the patella tendon; hip-width di erences a ecting knee alignment; gender biomechanics such as joint exibility, hormones and menstrual cycles; plus potentially gender di erences in early football training.

The risk of re-tearing a previously healed ACL is also higher. Therefore, to safeguard our players’ ongoing ligament health, and to avoid further time o the pitch, we would increase the frequency of ultrasound or MRI examinations on that individual. Furthermore, the amount of known research in this area means that we can be preventative at the outset with all our female players.

The value of dedicated research work in female sport

An ACL injury is a key example of how concentrated research and knowledge development over the years has enabled a greater understanding of how to avoid and monitor such injuries. As a result, we now look to strengthen all female players’ muscles that support the knee such as quadriceps and hamstrings, plus undertake landing control as part of our preventative strategies. This has helped in bringing down the number of ACL injuries by looking at recent FA Women’s Super League injury data.

Another area of injury prevention and monitoring is concussion. Again, a lot has been written about the long-term e ects of head injuries through head contact in football in male players, particularly its links with memory loss and Alzheimer’s Disease. So, practical exploratory work in a sports setting into diagnosing and monitoring for Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) using diagnostic imaging in our female players is a real focus, alongside our men.

Indeed, recent studies suggest that female athletes are not only more suspectable to concussion than males, but also sustain more-severe

concussions5. There is, therefore, a need for more research in this area which we are very fortunate to be able to do within our imaging suite using AI-assisted CT and MRI technologies. A greater understanding through focused research would play a part in establishing concussion treatment protocols for clubs and the FA which would be of immense bene t to all.

These injury examples highlight the importance of ongoing collaboration, discussion and sharing of research in sports medicine. It will help create further understanding of how the female body, which has been studied less than male football counterparts, has injury weakness areas and how it needs to be monitored. For us, it is very important to build up a bank of ‘normative’ historical data of our female players having only had a professional female team for four years. Our data on male players is superb, which has been down to the day-to-day medical team and the links we have to industry, healthcare and academia. But now, as we progress with a women’s team, we need to gain appropriate baselines in our female players to compare and establish where we are nowto help us develop in the future. Thisis gaininginmomentum.

Even in recent times, despite the Covid19 pandemic, we were able to keep going with our annual cardiovascular pro ling and monitoring of players using ultrasound echocardiograms. It means we now have four years’ worth of valuable data and, if needed, can correlate any future cardiac concerns, themes or safeguarding with Covid-19 infection data of players.

On the ball with proactive sporting health

It’s early days for professional women’s football but we’ve come a long way already. It is exciting how much interest there is from supporter communities, inspiring young girls, through to the growth of professional female clubs in the league. As leaders in football medicine and with our good fortune of having a hospital-grade diagnostic imaging centre on site at our training complex, we owe it to the future of female football to stride ahead in exploring health equality. Yet, there is so much more we can still do, from exploring deeper menstrual monitoring to minimise symptoms and maximise energy availability, to the use of bone-density imaging and expanding involvement in AI-based health projects. Whatever the outcome in the next match, female footballers can be assured that we’re on the ball with proactive sporting health. //

References

1 Anterior cruciate ligament rupture: di erences between males and females. Sutton KM,

Bullock JM. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013

Jan;21(1):41-50. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-21-01-41. 2 ACL Injury prevention in female athletes: review of the literature and practical considerations in implementing an ACL prevention program. Voskanian N. Curr Rev

Musculoskelet Med. 2013;6(2):158-63 3 The female ACL: Why is it more prone to injury?.

J Orthop. 2016;13(2):A1-A4. 2016. doi:10.1016/

S0972-978X(16)00023-4 4 Provided by Canon Medical Systems UK 5 Sport-Related Concussion in Female Athletes:

A Systematic Review. N.K. McGroarty,

S.M. Brown, M.K. Mulcahey.

Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2325967120932306