34 minute read

Can Public Banking Help Individuals and Governments Finance Brighter Futures? A Public Banking Primer for a Post-COVID World

Virginia Policy Review 79

Can Public Banking Help Individuals and Governments Finance Brighter Futures? A Public Banking Primer for a Post-COVID World

Advertisement

By John Henry Vansant

Executive Summary

High costs and lack of trust in private banks impedes the ability of individuals, businesses, and local governments to utilize banking services and finance their futures. While the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these issues, the challenges facing individuals and communities reflect broader systemic inequities and barriers to fair banking access. These problems have led political leaders to consider public banking, a policy framework concerning the formation and operation of publicly chartered banks. Proponents argue that public banks can provide more affordable lines of credit and other resources for historically marginalized communities, while opponents warn that government involvement would upend the current banking sector. Polling has been limited, yet a few polls on specific public banking policies and broader sentiments on private bankers suggest that voters would be open to these reforms. As proponents and opponents square off over current proposals, research suggests that prominent policies in the public banking discourse, like public banks and postal banking, can be successfully implemented and expand access. Since public banking will play a role in debates over financial policy in a post-COVID world, this primer will provide an overview of the public banking discourse and offer key takeaways for policymakers to consider as proposals evolve.

Part One: Existing Problems with Our Banking System

Individuals, businesses, and local governments may not need the same services, yet the current American banking system inhibits people and entities alike from financing their pursuits. In 2019, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) found that over 20% of Americans are either “unbanked” or “underbanked.” These Americans either do not possess a bank account, or they use alternative institutions, such as predatory lenders, to supplement their bank account (FSC Majority Staff, 2021). When surveyed, these unbanked

80 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

Americans told the FDIC that “lack of trust” and fees were two of the major reasons why they did not have a bank account (FSC Majority Staff, 2021). For small businesses, weak relationships with a banking institution can impede their efforts to secure loans and receive relief during times of economic crisis. The tumultuous administration of Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) funds during the COVID-19 crisis demonstrated how poor banking access can jeopardize a business’s operation during a sudden economic downturn (Flitter, 2020; Stewart, 2020). The lack of trust and high costs of banking with private banks also impacts state and municipal governments when they try to pay for longterm initiatives, as fees and interest payments hinder the financing of infrastructure and other public projects (Dayen, 2017; Jones, 2018; McGhee & Judd, 2011). Whether they are an individual or a state government, all of these parties face similar challenges of cost, access to services, and trust when navigating the for-profit banking system. Furthermore, these issues exacerbate racial inequities between communities. Black and Latino households are more disproportionately unbanked or underbanked versus white households (FSC Majority Staff, 2021), and Black-owned businesses have historically struggled to secure loans due to explicit racial discrimination. As of 2016, Black-owned businesses secured loans at a fraction of the rate that white-owned businesses did, and these strained relationships only worsened the disparities in PPP loan rates during the COVID-19 crisis between Black- and white-owned businesses (Flitter, 2020; Stewart, 2020). This entrenched lack of access to “mainstream" banking services also forces Black households to engage with predatory lenders who take advantage of their clients through high fees. Ultimately, the consequences of unfair banking access continue to fuel the racial wealth gap between Black and white households (Solomon et al., 2020). The intersection of banking challenges with systemic issues like institutional racism thus reflects the importance of reforming the banking system so that all individuals, businesses, and governments can utilize basic services, build wealth, and finance their endeavors.

Part Two: What is Public Banking?

Public banking refers to the establishment and operation of a bank by a governmental entity. The types of services provided by public banks include

Virginia Policy Review 81

financing options for state and municipal governments, as well as lending opportunities for businesses and individuals (Stewart, 2020). Accordingly, policy prescriptions under the public banking framework range from providing banking accounts at previously existing public institutions, such as the post office, to capitalizing an entire banking enterprise (Stewart, 2020). Governments across the country have either implemented or explored some variation of public banking; North Dakota has operated a bank since 1919, and California passed legislation in 2019 to allow local governments to establish their own banks (Kodrzycki & Elmatad, 2011; Koran, 2019). Developed over a century of experimentation and analysis, public banking has come to represent a host of policies that governments can consider to expand financing options for themselves, for individual constituents, and for businesses in their community.

Figure 1: Map of recent public bank initiatives (The National Movement – Alliance for Local Economic Prosperity, 2020)

Brief Review of Recent Federal Legislation Members of Congress have introduced several public banking bills in recent years, and while legislation has not advanced out of committee yet, legislators have increasingly considered these policies. Analyzing recent legislative history suggests that these policies have momentum behind them. While public banking’s nascency on the national level helps explain the lack of

82 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

prior success, reticence in Congress and across federal agencies complicates the translation of intrigue and support into legislative action. Public banking legislation has ranged in scope, yet four major proposals have emerged in recent years: comprehensive public banking, “postal banking,” “FedAccounts,” and a national infrastructure bank. Comprehensive public banking legislation would establish a federal framework for assisting states and localities that choose to establish their own public banks in addition to postal banking, government-backed bank accounts, and other federally provided services. Although communities have explored public banking for over a century (“History of BND,” 2022), Congressional momentum for facilitating public bank formation has only coalesced in recent years. Nevertheless, the House Subcommittee on Consumer Protection & Financial Institutions’ July 2021 hearing on the Public Banking Act, sponsored by Congresswomen Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and Rashida Tlaib (D-MI), demonstrates the subcommittee’s interest in public banking (FSC Majority Staff, 2021; Public Banking Act of 2021). First introduced in 2020 (Tlaib, 2020), the Public Banking Act would implement a regulatory framework and grant program that would promote local public banks, postal banking, and personal accounts with the Federal Reserve (Stewart, 2020; Tlaib, Ocasio-Cortez Introduce Legislation Enabling Creation of Public Banks, 2020; Public Banking Act of 2021). In addition to this bill, legislators have also included comprehensive public banking in other policy proposals, from affordable housing to the Green New Deal (Ocasio-Cortez, 2021; Waters, 2021).

Meanwhile, efforts to re-establish banking options through the United States Postal Service (USPS) have resurged in recent years. The Postal Service provided basic banking services through its post offices from 1910 until the 1960’s, and a 2014 report from the USPS Inspector General found that the agency could receive $9 billion in revenue by restarting postal banking (Estes, 2021). This contemporary analysis bolstered Senator Kirsten Gillibrand’s (DNY) rationale for introducing the Postal Banking Act in 2018 and 2020 (K. Gillibrand, 2020; K. E. Gillibrand, 2018, 2020; Senators Gillibrand and Sanders Reintroduce Postal Banking Act, 2020). While these bills and their companions have not advanced out of committee yet, Gillibrand and other legislators continue to bring attention to postal banking and integrate it into other bills, from

Virginia Policy Review 83

comprehensive public banking bills to “FedAccounts” legislation banking (FSC Majority Staff, 2021; Access to No-Fee Accounts Act, 2021; Public Banking Act of 2021; Stewart, 2020). Additionally, the American Postal Workers Union and Postmaster General Louis DeJoy have formed an unlikely alliance to pilot a limited version of postal banking at a handful of post offices. USPS officials have expressed support for using the pilot to decide whether they should provide reloadable gift cards, which would fundamentally serve as basic checking accounts. This would result in a de facto implementation of postal banking, although in a less ambitious form than the system proposed in Gillibrand’s postal banking legislation (Dayen, 2021a, 2021b; K. Gillibrand, 2020; K. E. Gillibrand, 2018, 2020; Senators Gillibrand and Sanders Reintroduce Postal Banking Act, 2020). Several legislators have also championed “FedAccounts,” free digital bank accounts backed by the Federal Reserve. Proposed in a discussion draft that the House Subcommittee on Consumer Protection & Financial Institutions debated during their July 2021 hearing, FedAccounts would allow the federal government to expand banking services through community banks, post offices, and other existing institutions (FSC Majority Staff, 2021; Access to No-Fee Accounts Act, 2021). In 2020, the chairs of two critical committees introduced FedAccounts legislation: Congresswoman Maxine Waters (D-CA), who chairs the House Committee on Financial Services, and Senator Sherrod Brown (DOH), who leads the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs (Brown, 2020; Waters, 2020). With the support of these powerful legislators, the policy continues to interest Congressional committees. Legislators have proposed the formation of a national infrastructure bank to finance long-term transportation and housing projects since the 1980’s, yet the policy did not gain momentum in Congress until 2007 when Senators Chuck Dodd (D-CT) and Chuck Hagel (R-NE) introduced bipartisan legislation to create such a bank (Dodd, 2008). Congress almost established the bank via the 2009 budget package, yet the proposal fell from this apogee after staunch Republican opposition and insufficient support from Democratic leadership (Davis, 2016). A decade later, legislators continue to propose the formation of a national infrastructure bank, yet these bills have not advanced out of committee (Davis, 2021). Like comprehensive public banking legislation, some legislators

84 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

have incorporated this policy in their pursuit of another objective, such as affordable housing (Waters, 2021).

Part Three: Support and Opposition for Public Banking

These public banking proposals have fueled debates within Congress and the executive branch, as legislators and allied interest groups have squared off over the role that the federal government should play in the banking industry.

Supporters Supporters in Congress, the White House, and across the country have argued that public banking services can ameliorate banking inequities that private institutions have failed to address. In a 2020 joint press release with Rep. Tlaib, Rep. Ocasio-Cortez stated that public banks “are uniquely able to address the economic inequality and structural racism exacerbated by the banking industry’s discriminatory policies and predatory practices” (Tlaib, Ocasio-Cortez Introduce Legislation Enabling Creation of Public Banks, 2020). At the July 2021 hearing on public banking, Rep. Ocasio-Cortez specified these claims, arguing that public banks could extend affordable lines of credit to individuals and businesses from communities “that Wall Street has deemed unprofitable” (Banking the Unbanked, 2021; U.S. House Committee on Financial Services, 2021). During this hearing, Representatives Ocasio-Cortez, Tlaib, and Waters emphasized the need for public intervention by citing the high rates of unbanked and underbanked populations in their districts, particularly within communities of color (Banking the Unbanked, 2021; U.S. House Committee on Financial Services, 2021). Senator Gillibrand also highlighted the issue of banking access in a 2020 op-ed advocating for postal banking, emphasizing that banking services in post offices could help her constituents and other Americans avoid costly, predatory alternatives (Gillibrand, 2020). Meanwhile, President Joe Biden joined his fellow Democrats on the campaign trail to tout postal banking and FedAccounts as “affordable, transparent, trustworthy banking services for low- and middle-income families” (Biden-Sanders Unity Task Force Recommendations, 2020; Matthews, 2020; Shaw, 2020). These arguments from key Democratic leaders reflect proponents’ dissatisfaction with the current banking system and their belief in the ability of

Virginia Policy Review 85

public institutions, from new public banks to the Postal Service, to close gaps in banking access and provide key services for historically marginalized communities. What unites these disparate groups is the belief that public banking solutions, from public banks to postal banking, can provide key services at lower costs than for-profit institutions and that individuals, businesses, and governments can trust public entities to conduct their affairs in accordance with their community’s interests. When they testified during the July 2021 hearing on public banking, advocates from the New Economy Project and Economic Security Project emphasized the role these banks can play in helping governments invest their funds in infrastructure and other public initiatives. They asserted that, in addition to the trustworthy retail banking that these policies could establish for individuals and businesses, public banking institutions could also create new avenues of investment to facilitate other policies, such as affordable housing, COVID-19 relief, and clean energy infrastructure (Banking the Unbanked, 2021; U.S. House Committee on Financial Services, 2021). Supporters therefore frame public banks and other policies as solutions that provide cheaper services for individuals and businesses as well as long-term financing options for governments that directly benefit projects in their communities. Their statements reflect a core value in the movement for public banking: that a mission oriented around the public, not private shareholders, changes the nature of a bank and the services it provides to a community.

Opponents Conservative legislators, reticent policymakers, and outside interest groups have criticized public banking solutions on the grounds that they interfere with the existing private banking system, which can efficiently resolve equity issues on its own. In Congress, Republicans have lambasted the fundamental idea that public banking institutions could provide efficacious services for underserved communities. Congressman Andy Barr (R-KY) has summarized the Republican committee members’ overall views on public banking: it would be like “asking the arsonists to put out the fire” (Banking the Unbanked, 2021; U.S. House Committee on Financial Services, 2021). For conservative lawmakers, public

86 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

banking legislation would result in a “government takeover” that would upend the banking industry and jeopardize existing services (Banking the Unbanked, 2021; U.S. House Committee on Financial Services, 2021). In hearings, Republican legislators have sought to counter proponents’ arguments on equity by citing rural communities, areas that they characterize as underserved yet unsuited for public banking (Banking the Unbanked, 2021; U.S. House Committee on Financial Services, 2021). Interestingly, reformers originally established the Bank of North Dakota (BND), the only state public bank in the country, to support rural communities spurned by Wall Street banks (Kodrzycki & Elmatad, 2011). However, Republicans called for deregulating banking and incentivizing private actors to invest in these underbanked areas services (Banking the Unbanked, 2021; U.S. House Committee on Financial Services, 2021). Despite concerns for unbanked and underbanked constituencies that mirror those shared by lead sponsors, opponents have no desire to expand public services into a sector that they believe is well-serviced by private actors. While the attacks on public banking from conservative legislators reflect the most ardent forms of opposition, other policymakers have expressed reticence about public banking solutions on similar grounds. The Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell, told the House Committee on Financial Services during a June 2020 hearing that personal FedAccounts would be “a dramatic change” that could upend the current banking market. He elaborated on his hesitance, stating that “he would worry about what would happen to the rest of our private banking system” after the introduction of retail banking through the Federal Reserve and subsequent changes in consumer behavior (Monetary Policy and the State of the Economy, 2020; Lane, 2020). Although these comments are softer in tone, they express similar concerns that Republican lawmakers asserted: that public banking policies, from local banks to government-backed bank accounts, could result in system-wide costs that exceed the benefits in access and equity that they produce. Private bankers and allied interest groups have echoed these concerns in their staunch opposition to public banking, arguing that these policies’ could jeopardize the private industry’s efficient allocation of services and resources. Private bankers have fought against public banking policies like postal banking for over a century (Shaw, 2018), and they have announced their criticisms of

Virginia Policy Review 87

recent legislation as unnecessary interventions in their industry. The American Banking Association believes that public banks are “redundant in the current marketplace, where financial offerings already efficiently meet customer needs,” and could be “dangerous,” as governments would place “taxpayer funds in institutions that may not have deposit insurance and whose business decisions will be driven by political priorities instead of sound risk management” (Public Banks, 2022). In written testimony submitted for the July 2021 hearing on public banking, the Consumer Bankers Association argued that public banking solutions would jeopardize the “competitiveness” of private banks and the services that they provide, which would harm existing private institutions (Banking the Unbanked, 2021). While supporters claim that private banks are failing to address gaps in access and inequitable services, private bankers claim that they have achieved a desirable balance of equity and efficiency that the government could upheave through public banking. For these groups, the current market that supporters criticize instead reflects a market that only needs minor adjustments from current actors to re-allocate resources to underserved communities.

Part Four: Public Support for Public Banking

Figure 2: Topline Polling Data on Postal Banking (Gillibrand, 2020)

88 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

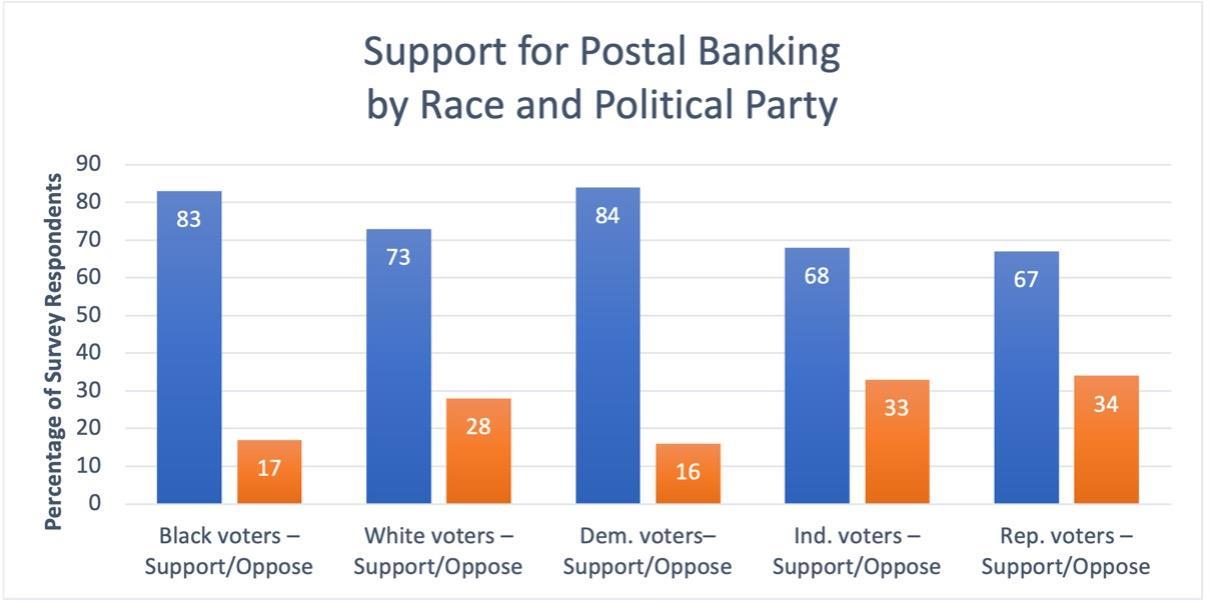

Gauging public support for the broad schema of public banking is challenging, yet recent polling on postal banking, government-backed bank accounts, and Wall Street entities illustrate the openness of American voters to public banking policies. Figure 3 highlights how, in a May 2020 poll, Data for Progress found that 74% of voters support postal banking, and strong supporters outnumbered strong opponents by a 28–11 margin. As shown in Figure 4, Black voters supported postal banking by an even larger margin than white voters, and the policy received strong bipartisan support, including twothirds of Republican and Independent voters (Gillibrand, 2020). While the toplines presented in Figures 3 and 4 suggest that broad swaths of voters support postal banking, it is important to note that Data for Progress qualified the question by asking voters whether they support postal banking “if the revenue raised stops the closure of post offices and the elimination of services, such as weekend delivery” (Gillibrand, 2020). The USPS Inspector General’s 2015 report provides concrete evidence that postal banking would generate the revenues necessary for preserving current services (Estes, 2021; Gillibrand, 2020), yet the inclusion of this positive consequence in the question could have swayed some respondents to voice greater support than they would have without any context.

Figure 3: Support for Postal Banking, by Race and Political Party (Gillibrand, 2020)

Virginia Policy Review 89

Polling on government-backed bank accounts reflects a similar dynamic of qualified openness. According to a report released by Data for Progress and the Justice Collaborative Institute, large bipartisan majorities of voters support digitized, government-backed accounts. Over 59% of voters surveyed backed the policy and characterized key arguments in favor of it as strongly or somewhat “convincing,” including half of all Republicans (Hockett, 2020). However, these questions provide evidence for support after voters evaluated reasons to support digital dollar accounts. They did not test the possibility that voters may have to consider counterarguments at the same time, a likely scenario if the policy arises as an issue on the campaign trail or in a ballot referendum. The polling data thus provides specific yet qualified evidence for voter support behind digitized accounts, as voters’ openness to public banking solutions could be more nuanced or volatile than captured by these polls. Analyzing the public’s view of the current banking industry also explicates current and potential appetites for public banking reforms. Recent polling from the Pew Research Center showed that voters are split on their attitudes towards banks, as 49% of respondents said that banks have “a positive effect on the way things are going in the country” versus 48% who claimed that banks have a “negative effect” (Green, 2021). However, voters’ views shift when they consider corporate “Wall Street” banks. In a June 2020 survey, Change Research found that voters viewed Wall Street banks unfavorably by a 53-12 margin (States of Play: Battleground & National Likely Voter Surveys on The Economy, COVID-19 & Racism, 2020). Considered together, these data points suggest that while voters are divided over banks in general, they share common concerns about corporate banks. This may shape the electorate’s opinion on public banking, especially if they view public banks and government services as preferable alternatives to Wall Street institutions.

Part Five: Recent Research

The question of whether Congress should encourage the formation of public banks and related services through funding and regulation hinges on whether public banking options can expand services to historically marginalized populations and direct more funds towards local investments. This brief overview of recent research on prominent public banking solutions illustrates

90 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

the potential benefits that public banking could provide to communities that wish to undertake the process of establishing new services for their constituents.

Public Banking Proponents and opponents alike cite BND in their evaluations of public banking, so analyzing BND’s performance helps illustrate both the positive attributes of a public bank and potential limitations communities may face. The last state bank in existence, BND arose from a movement led by progressive farmers and activists who translated widespread discontent with out-of-state banks and their unfair lending practices into new majorities in the 1918 elections. Despite North Dakota’s subsequent evolution as a conservative state, the Bank of North Dakota continues to operate with broad support from voters and leaders alike (“History of BND,” 2022; Kodrzycki & Elmatad, 2011; McGhee & Judd, 2011). BND thus provides a long-standing example of public banking for analysts to examine.

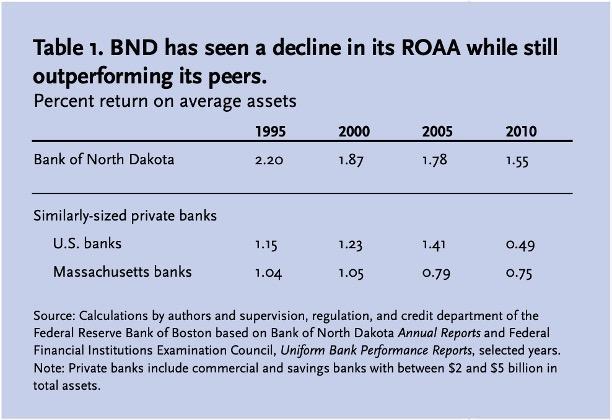

Table 1: The Bank of North Dakota's Returns, Relative to Private-Sector Peers (Kodrzycki & Elmatad, 2011)

Studies of BND suggest that public banks could successfully provide key services in a local banking market, yet high launch costs would impede

Virginia Policy Review 91

other states’ efforts to launch their own bank. Table 1 shows how BND has consistently out-performed peer private banks, even as its returns have declined in recent decades (Kodrzycki & Elmatad, 2011). Studies have also found that North Dakotans view BND favorably. As the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston noted in their report, BND operates “conservatively within an overall environment in North Dakota that favors conservatism,” prioritizing low-risk loans and partnerships with community banks to expand services in areas historically neglected by Wall Street firms (Kodrzycki & Elmatad, 2011). However, studies disagree over the influence of BND on North Dakota’s economy. The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston argued that BND’s impact on North Dakota’s economic stability seems to be “minor” (Kodrzycki & Elmatad, 2011). A Dēmos study reached a different conclusion, finding that BND’s aggressive lending and community bank assistance helped North Dakota secure a surplus, cut taxes, mitigate the uptick in foreclosures, and maintain nationleading employment rates – all without any downsizing (McGhee & Judd, 2011). Regardless of BND’s efficacy, the costs of capitalizing a similar bank would be high; for Massachusetts, it could cost over $3.6 billion (Kodrzycki & Elmatad, 2011). These nuanced evaluations of BND intimate that public banks can thrive and earn the support of a community. However, states and municipalities must decide for themselves whether they should dedicate huge sums of funds to launch their own bank.

Postal Banking Unlike public banks, the United States had implemented a postal banking system for over fifty years during the 20th century (Estes, 2021). Research on the policy has therefore concerned both the history and efficacy of postal banking during its operation (Baradaran, 2014; Shaw, 2018) as well as the potential benefits that new postal banking services could bring to communities in a post-COVID world (Friedline et al., 2021). While opponents may cite the discontinuation of postal banking in the 1960s as evidence of its failure, reviewing the history of the program presents a more ambiguous picture, as postal banking thrived when political leaders did not direct consumers and their deposits away from the service. A product of progressive and socialist organizing, postal banking swiftly grew due to the diverse array of Americans that utilized the service, ranging from immigrant

92 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

communities in New York City to agricultural towns across the Midwest (Shaw, 2018). When the banking sector collapsed during the Great Depression, more Americans directed their deposits towards the Postal Service. In the early 1930s, deposits in postal banking services surpassed $1 billion, around ten percent of the assets in the commercial banking industry (Baradaran, 2014; Shaw, 2018). Strong opponents of postal banking since its inception, private bankers feared that the Great Depression would result in reforms that could further expand the Postal Service’s presence in the banking sector and encourage more Americans to move their accounts to the Postal Service. However, disinterest from the Postmaster General and the White House stalled any expansion of postal banking. This portended the ultimate decline of postal banking; while postal banking grew to an apogee of $3.4 billion in deposits and four million consumers in 1947, persistent pressure from private bankers coupled with apathy from lawmakers fueled its multi-decade rollback and ultimate termination (Baradaran, 2014; Shaw, 2018). Rather than reflecting the inadequacies of the policy itself, the history of postal banking instead illustrates the political tug-of-war between reformers and bankers. Postal banking may have grown from its heights in 1930s and 1940s if legislators, administrators, and interest groups had defended the program from the intense campaign that the banking industry waged against postal banking for decades. As advocates look to resurrect postal banking, recent research suggests that these services could have a particular impact in communities that have post offices yet cannot access local banking services. In 2021, Terri Friedline and other researchers found that across the United States, nearly 70% of census tracts with a post office lack a bank or a credit union; these figures rise as high as 87–94% of census tracts in states like Arizona, California, and Idaho. Over 60 million Americans live in a census tract where postal banking could provide the only local banking services (Friedline et al., 2021). While critics like Sen. John Boozman (R-AR) argue that this emphasis on “brick-and-mortar” locations does not address the problems raised by unbanked individuals in official surveys (Boozman, 2021), Friedline and her co-authors argue that online banking does not provide adequate services for communities that lack sufficient internet access, including both rural areas and communities of color that experience high rates of disrupted phone and internet services. Furthermore,

Virginia Policy Review 93

they assert that the data reflects the broader inattention that private banks pay to these communities, which ultimately results in the lack of local investments made in these census tracts (Friedline et al., 2021). Equitable banking access will shape Americans’ financial recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic (Friedline et al., 2021; Solomon et al., 2020), and postal banking could extend basic services to millions of Americans across the country without upending existent community banks and credit unions.

Part Six: Key Takeaways for Policymakers in a Post-COVID World

The research highlighted above substantiates the need for exploring public banking solutions, as the gaps and inequities in banking access reflect the need for public intervention. The central disagreement that fuels the debate over public banking is whether inadequate banking services for certain communities reflects a systemic issue with the current banking sector that warrants government action. Researchers and advocates alike have convincingly linked public banking to longstanding inequities in banking access that have only worsened during the pandemic (Banking the Unbanked, 2021; Friedline et al., 2021; Solomon et al., 2020; U.S. House Committee on Financial Services, 2021). Furthermore, households and businesses from across the country feel the impact of subpar banking access, as the data above shows the private sector has not provided adequate services for low-income neighborhoods, rural areas, and communities of color nationwide (Friedline et al., 2021; Solomon et al., 2020). For expansive solutions like comprehensive public banking, the research suggests that Congress should establish a framework that allows communities to establish these institutions if they are willing to pay the high initial costs of capitalizing the bank. These banks may not work for all communities, yet BND’s success suggests that public banks could thrive in many communities across the country. On the simpler end, postal banking and FedAccounts could build upon existing agencies to increase banking services for millions of Americans without high implementation costs. Opponents will object to all of these policies due to the perceived threat of public intervention in the existing banking industry, yet the systemic issues that COVID-19 has exacerbated only demonstrate the need for competition from public institutions that will help those who have been neglected by current actors.

94 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

Public banking advocates have also convincingly made the case for the role of public banking in financing local public projects, and more research into this angle of public banking would help policymakers determine how public banks can improve public financing of critical projects. In addition to the public health crisis caused by COVID-19, states and localities across the country face several structural issues that will require massive investments in infrastructure and other long-term programs, from affordable housing to climate change. These local governments need more avenues to invest their funds in initiatives that will address these societal concerns, and public banks could provide financing opportunities that redirect public funds from Wall Street investments to local communities and their priorities (Banking the Unbanked, 2021; U.S. House Committee on Financial Services, 2021). Public banks could therefore serve as a conduit for democratizing and localizing government investments, so proponents and researchers alike should continue to explore this rationale, as it improves the case for comprehensive public banking. Since public banking encapsulates a family of related policies, proponents can take advantage of the variety of public banking legislation to pass some sort of policy package in the short term to advance the broader conception of public banking in the long term. For Members and advocates seeking to carry future public banking bills, recent legislative history illustrates a promising yet complicated picture; while legislators are considering several public banking solutions, none of them have passed out of committee. Of course, the Republican response to public banking during the July 2021 hearing suggests that this has been likely due to the Congressional power they have held since 2011 (Banking the Unbanked, 2021; U.S. House Committee on Financial Services, 2021). As lead sponsors and coalition leaders plan their push for legislation, they should gauge the relative momentum surrounding each policy and pressure Congressional representatives to pass some sort of package. This would require de-emphasizing the national infrastructure bank, as that policy has failed to advance since 2007, and rallying behind solutions like postal banking and FedAccounts, two complementary policies that have received support from key Democratic chairpersons and gatekeepers. While the Public Banking Act has only emerged in the last year, presenting it concurrently with this combination could help sponsors frame these smaller policies as palatable compromises, swaying swing votes and improving the chance of advancing any

Virginia Policy Review 95

public banking bill. By running the Public Banking Act alongside postal banking and FedAccounts, advocates could generate enthusiasm for the broader principles of public banking and increase the odds of passing legislation. As proponents act to enact public banking legislation, they should capitalize on the public’s seemingly open attitude towards public banking and negativity towards Wall Street banks to build public support for services that depend on the public’s trust. Although the polls described above do not directly test the popularity of “public banking” nationwide, they highlight how voters across the spectrum back public banking policies when they hear basic reasons for implementation. While proponents may embrace these results, the questions posed by pollsters presented solutions in a favorable light, which may distort the strength of voters’ support. Nevertheless, underlying concerns about Wall Street banks may provide policymakers with an avenue to present public banking measures to constituents in a manner that appeals to a bipartisan majority. These surveys do not substantiate firm conclusions on voters’ attitudes, yet they highlight the promise of a receptive electorate to public banking. Public banking is sound policy for banking reforms in a post-COVID world, and the potential political benefits of expanding banking services across various constituencies highlight the possibility that public banking could be a winning issue on the campaign trail. Looking forward to the 2022 election cycle, an incumbent or challenger could distinguish themselves on the issue of banking access by advocating for public banking policies on the campaign trail. As previously noted, over 20% of Americans either do not have any bank accounts or cannot access the services that they need (FSC Majority Staff, 2021), and most voters hold unfavorable views towards Wall Street banks (Green, 2021; States of Play: Battleground & National Likely Voter Surveys on The Economy, COVID-19 & Racism, 2020). For any political candidate, these data points suggest that proposing solutions that attempt to expand services in underserved communities and shift power away from corporate entities would garner support among a broad swath of the electorate. Public banking could also entice Democratic, Republican, and independent voters alike, as bipartisan majorities backed postal banking in the polling described earlier (Gillibrand, 2020; Hockett, 2020). Furthermore, campaigns can concretely explicate policies like postal banking to their audience of target voters; a majority of the electorate supports the Postal Service (Kirby, 2020), and since they can easily visualize

96 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

their local post office, voters will likely understand how a postal banking system could help them or their neighbors bank. Candidates could therefore sway voters with public banking measures if they clearly communicate how these policies will improve banking access in their communities.

John Henry Vansant is a first year MPP/JD student at the University of Virginia Frank Batten School for Leadership & Public Policy and the University of Virginia School of Law. Prior to Virginia, he graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Wesleyan University (CT) with high honors. From 2018-2021, he worked as a legislative aide and campaign manager in Colorado, and he served as Internal Vice Chair of the Boulder County Democratic Party. He was proud to join his co-workers in establishing the Political Workers Guild of Colorado, one of the first unions to represent legislative and campaign staff in the country.

Virginia Policy Review 97

References

2020 election: Where the candidates stand on banking. (2020, April 8). Banking Dive. https://www.bankingdive.com/news/2020-election-where-the-candidatesstand-on-banking/559553/ 2020 Map of Public Banking efforts in US. (2018, October 4). People for Public Banking Central Coast. https://peopleforpublicbanking.com/2018/10/04/map-ofpublic-banking-efforts-in-us/ Access to No-Fee Accounts Act. (2021). U.S. House, Subcommittee on Consumer Protection & Financial Institutions. https://financialservices.house.gov/uploadedfiles/bills-117pih-theaccesstonofeeaccountsact.pdf Baradaran, M. (2014a). It’s Time for Postal Banking. Harvard Law Review, 127(4). https://harvardlawreview.org/2014/02/its-time-for-postal-banking/ Baradaran, M. (2014b, August 18). A Short History of Postal Banking. Slate. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2014/08/postal-banking-already-workedin-the-usa-and-it-will-work-again.html Biden-Sanders Unity Task Force Recommendations. (2020). Democratic National Committee. https://joebiden.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/UNITYTASK-FORCE-RECOMMENDATIONS.pdf Boozman, J. (2021, December 1). Postal Service expansion into banking services misguided. The Hill. https://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/politics/583864-postalservice-expansion-into-banking-services-misguided Brown, S. (2020, June 30). Text - S.3571 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): A bill to require member banks to maintain pass-through digital dollar wallets for certain persons, and for other purposes. (2019/2020) [Legislation]. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116thcongress/senate-bill/3571/text Conti-Brown, P. (2018, May 31). Why the next big bank shouldn’t be the USPS. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/why-the-next-big-bank-shouldnt-be-theusps/ Davis, D. K. (2021, May 20). Text - H.R.3339 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): National

Infrastructure Bank Act of 2021 (2021/2022) [Legislation]. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/3339/text Davis, J. (2016, August 3). A History of Infrastructure Bank Proposals. Enos Center for Transportation. https://www.enotrans.org/article/look-infrastructure-bankspart-1/

98 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

Dayen, D. (2017, April 17). A Bank Even a Socialist Could Love. In These Times. https://inthesetimes.com/article/the-fight-for-public-banking Dayen, D. (2021a, October 4). USPS Begins Postal Banking Pilot Program. The American Prospect. https://prospect.org/api/content/55664c28-24a9-11ec-84ba12f1225286c6/ Dayen, D. (2021b, November 9). Postal Banking Test in the Bronx Yields No Customers. The American Prospect. https://prospect.org/api/content/2345e00a-40d811ec-998a-12f1225286c6/ Dodd, C. J. (2008, June 12). Text - S.1926 - 110th Congress (2007-2008): National

Infrastructure Bank Act of 2007 (2007/2008) [Legislation]. https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/senate-bill/1926/text Estes, A. C. (2021, January 22). How the Biden administration can save the Postal Service. Vox. https://www.vox.com/recode/22243799/post-office-delays-postalbanking-usps-reform Flitter, E. (2020, April 10). Black-Owned Businesses Could Face Hurdles in Federal Aid

Program. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/10/business/minority-businesscoronavirus-loans.html Friedline, T., Wedel, X., Peterson, N., & Pawar, A. (2021). Postal Banking: How the United States Postal Service Can Partner on Public Options. Poverty Solutions at the University of Michigan, 35. FSC Majority Staff. (2021). Committee Memorandum – Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Financial Institutions hearing entitled, “Banking the Unbanked: Exploring Private and Public Efforts to Expand Access to the Financial System.” U.S. Congress, House, Subcommittee on Consumer Protection & Financial Institutions. https://financialservices.house.gov/uploadedfiles/hhrg-117-ba15-20210721sd002.pdf Gillibrand, K. (2020a, April 26). Trump Called the Postal Service a ‘Joke.’ I’m Trying to Save

It. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/26/opinion/kirsten-gillibrand-uspscoronavirus.html Gillibrand, K. (2020b, July 14). Voters Support Postal Banking. Data For Progress. https://www.dataforprogress.org/blog/2020/7/14/voters-support-postalbanking

Virginia Policy Review 99

Gillibrand, K. E. (2018, April 25). Text - S.2755 - 115th Congress (2017-2018): Postal

Banking Act (2017/2018) [Legislation]. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115thcongress/senate-bill/2755/text Gillibrand, K. E. (2020, September 17). Text - S.4614 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): A bill to amend title 39, United States Code, to provide that the United States Postal Service may provide certain basic financial services, and for other purposes. (2019/2020) [Legislation]. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senatebill/4614/text Green, T. V. (2021, August 20). Republicans increasingly critical of several major U.S. institutions, including big corporations and banks. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/08/20/republicans-increasinglycritical-of-several-major-u-s-institutions-including-big-corporations-and-banks/ History of BND. (2022). Bank of North Dakota. https://bnd.nd.gov/history-of-bnd/ Hockett, R. (2020). The Inclusive Value Ledger – Digital Dollars and Digital Platforms for

Digital Public Banking. The Justice Collaborative Institute. https://30glxtj0jh81xn8rx26pr5af-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wpcontent/uploads/2020/12/Digital-Dollars-2.pdf House Committee on Financial Services. (n.d.). GovTrack.Us. Retrieved February 6, 2022, from https://www.govtrack.us/congress/committees/HSBA Monetary Policy and the State of the Economy, 116th Congress, 2nd Session (2020) (testimony of Congress House of Representatives). https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/CHRG116hhrg42941/https%3A%2F%2Fwww.govinfo.gov%2Fapp%2Fdetails%2FC HRG-116hhrg42941%2FCHRG-116hhrg42941 Banking the Unbanked: Exploring Private and Public Efforts to Expand Access to the Financial

System, 117th Congress, 1st Session (2021) (testimony of Congress House of Representatives). https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/CHRG117hhrg45508/https%3A%2F%2Fwww.govinfo.gov%2Fapp%2Fdetails%2FC HRG-117hhrg45508%2FCHRG-117hhrg45508 Jones, S. (2018, August 10). Why Public Banks Are Suddenly Popular. The New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/article/150594/public-banks-suddenly-popular Kirby, J. (2020, September 2). American voters support the post office. Their views on mail-in voting are more complicated. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2020/9/2/21410124/poll-postal-service-voters-voteby-mail

100 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

Kodrzycki, Y. K., & Elmatad, T. (2011). The Bank of North Dakota: A Model for

Massachusetts and Other States?. (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 1932426). Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1932426 Koran, M. (2019, October 4). California just legalized public banking, setting the stage for more affordable housing. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/usnews/2019/oct/03/california-governor-public-banking-law-ab857 Lane, S. (2020, July 8). Biden-Sanders unity task force calls for Fed, US Postal Service consumer banking. TheHill. https://thehill.com/policy/finance/506469-biden-sandersunity-task-force-calls-for-fed-us-postal-service-consumer Legislation by State. (2022). Public Banking Institute. https://publicbankinginstitute.org/legislation-by-state/ Matthews, D. (2020, November 19). 10 enormously consequential things Biden can do without the Senate. Vox. https://www.vox.com/21557717/joe-biden-executive-orderstudent-debt-climate McGhee, H. C., & Judd, J. (2011). Banking On America. Dēmos. https://www.demos.org/policy-briefs/banking-america Nguyen, L., & Epstein, J. (2020, November 15). Biden Fills Economic Posts With Experts on Systemic Racism. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-11-15/biden-fills-economicposts-with-experts-on-systemic-racism Ocasio-Cortez, A. (2021, October 19). Text - H.Res.332 - 117th Congress (2021-2022):

Recognizing the duty of the Federal Government to create a Green New Deal. (2021/2022) [Legislation]. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/houseresolution/332/text Public Banking Act of 2021. (2021). U.S. House, Subcommittee on Consumer Protection & Financial Institutions. https://financialservices.house.gov/uploadedfiles/bills-117pihthepublicbankingactof2021.pdf Public Banks. (2022). American Bankers Association. https://www.aba.com/advocacy/our-issues/public-banks Senators Gillibrand And Sanders Reintroduce Postal Banking Act To Fund United States Postal

Service And Provide Basic Financial Services To Underbanked Americans | Kirsten

Gillibrand | U.S. Senator for New York. (2020, September 17). https://www.gillibrand.senate.gov/news/press/release/senators-gillibrand-and-

Virginia Policy Review 101

sanders-reintroduce-postal-banking-act-to-fund-united-states-postal-serviceand-provide-basic-financial-services-to-underbanked-americans Shaw, C. (2020, July 21). Postal banking is making a comeback. Here’s how to ensure it becomes a reality. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/07/21/postal-banking-ismaking-comeback-heres-how-ensure-it-becomes-reality/ Shaw, C. W. (2018). “Banks of the People”: The Life and Death of the U.S. Postal Savings System. Journal of Social History, 52(1), 121–152. https://doi.org/10.1093/jsh/shx036 Solomon, D., Baradaran, M., & Roberts, L. (2020, October 15). Creating a Postal

Banking System Would Help Address Structural Inequality. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/creating-postal-bankingsystem-help-address-structural-inequality/ States of Play: Battleground & National Likely Voter Surveys on The Economy, COVID-19 &

Racism. (2020). Change Research. https://drive.google.com/file/d/18zrf4szzSaU08mqpsgkkoRNODZty4GOy/v iew?usp=embed_facebook Stewart, E. (2020a, July 13). The PPP worked how it was supposed to. That’s the problem. Vox. https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/7/13/21320179/ppp-loans-sbapaycheck-protection-program-polling-kanye-west Stewart, E. (2020b, October 30). Exclusive: Rashida Tlaib and AOC have a proposal for a fairer, greener financial system — public banking. Vox. https://www.vox.com/policyand-politics/21541113/rashida-tlaib-aoc-public-banking-act Tlaib, Ocasio-Cortez Introduce Legislation Enabling Creation of Public Banks. (2020, October 30). Representative Rashida Tlaib. https://tlaib.house.gov/tlaib-aoc-publicbanking-act Tlaib, R. (2020, October 30). H.R.8721 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): To provide for the

Federal charter of certain public banks, and for other purposes. (2019/2020) [Legislation]. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/8721 The National Movement – Alliance for Local Economic Prosperity. (2020). https://aflep.org/the-national-movement-resources/ U.S. House Committee on Financial Services. (2021, July 21). Banking the Unbanked:

Exploring Private and Public Efforts to Expand Access to... (EventID=113948). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L5UUeZAhNks

102 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

Waters, M. (2020, March 23). Text - H.R.6321 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): Financial Protections and Assistance for America’s Consumers, States, Businesses, and Vulnerable

Populations Act (2019/2020) [Legislation]. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6321/text Waters, M. (2021, July 22). Text - H.R.4497 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): Housing is

Infrastructure Act of 2021 (2021/2022) [Legislation]. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/4497/text Who We Are. (2021). Public Bank NYC. https://www.publicbanknyc.org/about