43 minute read

Building a Resilient Future: The Hidden Power of Nature-Based Climate Solutions

Virginia Policy Review 11

By Sophie Mariam

Advertisement

ABSTRACT

Climate change will disproportionately harm women, and gendered disparities within everyday economic and social structures are deeply intertwined with women’s vulnerability to climate risks such as extreme weather events. The increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events has laid bare the gaping holes in our disaster preparedness, as well as the inequitable effects of climate-related natural disasters on women. Extreme-weather disasters result in higher mortality rates for women, higher risk of gender-based violence, and poorer neonatal health outcomes. These risks will only be exacerbated by the onslaught of extreme weather events in coming decades, as anthropogenic climate change stacks the weather dice against women. Recent disaster-preparedness policy failures such as Hurricane Harvey illustrate the climate injustice we can expect if we continue down our current path of genderneutral policy responses. Ecofeminist criticism can give way to a new policy lens which explains how just as the subjugation of women holds us back from reaching our full economic potential, boxing our policy solutions to only “gray infrastructure” ideas will inhibit our climate policy goals. This analysis will sketch a policy roadmap for climate resilience in the United States, advancing four policy ideas to empower women living in flood-prone areas and unleash the potential of our natural world. States and localities should set aside a portion of Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act funds for green and resilient infrastructure in marginalized communities and amplify the impact of nature-based solutions by financing projects in harmony with discounted insurance premiums for low-income women and families. To ensure that green jobs are accessible to all Americans, equitable workforce development policy must uplift female and marginalized workers at risk of climate displacement. Finally, we should center the knowledge of indigenous women, who serve as exemplary stewards of the land, by empowering indigenous leadership to devise collaborative mitigation projects for floodplain management.

INTRODUCTION

Climate change continues to “roll the weather dice against us,” making it more likely that extreme floods will strike (Johnson et al, 2021). Despite the devastating impact of the COVID pandemic, climate change has continued to amplify the probability, severity, and frequency of extreme weather events.

12 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

From March 2020 until August 2021 alone, over 43 million people worldwide were impacted by 277 separate extreme flood events (Walton et al, 2021). These threats are already emerging, compounding on the economic hardships facing many of our nation’s most vulnerable communities, especially women and those holding multiple marginalized identities. Amidst the worst conditions of the pandemic in February 2021, nearly 4.5 million Texas homes and businesses were left without power due to extreme weather, and at least 57 people died as a result of the storm (Sparber, 2021). This devastation hit hardest for Texans already facing economic insecurity; there’s no means-test to determine if disaster will strike a family that never received the last stimulus check, or a female-led household that could not pay for flood insurance payments due to a bout of unemployment. The Texas blackout, like all environmental catastrophes, was not an equal-opportunity disaster. Women, particularly low-income women and women of color, were at higher risk (Carvallo et al, 2021; Dellinger, 2021). Areas with a high share of minorities were four times more likely to suffer from energy blackouts than predominantly white areas (Carvallo et al, 2021). Rates of domestic violence spiked and the capacity of shelters for women and children was stretched beyond the means of Texas’s emergency response infrastructure (Dellinger, 2021). The surge of gender-based violence after extreme weather events has been well documented throughout past disasters; rates of strangulation and domestic-violence-related murders increased in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey (Washington, 2021). One crisis center in Harris County, Texas reported 1,025 domestic violence victims from January-August 2018, compared with 417 for the same months in 2017 (Zurawski, 2018). After Hurricane Katrina in Louisiana and Mississippi, rates of intimate partner violence incidents for internally displaced persons living in travel trailer parks were three times higher than the U.S. average (Larrance et al, 2007). These harms persist long after disaster strikes; another study shows displaced women in Mississippi continued to face higher levels of gender-based violence two years after Hurricane Katrina (Anastario et al, 2009). Women’s health is also at risk, as well as the health of unborn children. A meta-analysis of 130 peer-reviewed studies, displayed in Figure 1, found that 68 percent (89) of 130 studies show that women were more affected by health

Virginia Policy Review 13

impacts associated with climate change than men (Dunne, 2021). Women and children are 14 times more likely than men to die during a disaster, and United Nations (UN) figures indicate that 80 percent of people displaced by climate change are women (United Nations Population Fund, 2021).

Figure 1: Source: Dunne, 2021

Make no mistake, humans are the driving force behind gender-biased climate catastrophes; Hurricane Harvey’s downpour was made around three times more likely and 15 percent more intense by anthropogenic climate change (Trenberth et al, 2018). But not only is climate change itself caused by anthropogenic patterns, humans have also constructed the social systems that lead extreme weather events to place a disproportionate burden on women. Anthropogenic climate change and the subjugation of women are inextricably linked; they are essentially conjoined twins. In a study utilizing a sample of up to 141 countries over the period from 1981 to 2002, women’s low socioeconomic status was directly linked to higher female death rates following environmental disasters (Neumayer and Plumper, 2007). However, fighting gender-based oppression may help address the harm of disasters as climate change leads to the increasing prevalence and severity of extreme weather events like floods and storms. The study also found that the higher the average

14 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

socioeconomic status of women was in any given country, the weaker the effect of disasters was on the measured gender gap in life expectancy. The authors conclude that the “socially constructed gender-specific vulnerability of females built into everyday socioeconomic patterns” is the true driver behind the gender gap in disaster mortality (Neumayer and Plumper, 2007; emphasis added).

While the climate is indeed changing, at the end of the day what citizens should care about is mitigating human harm and adapting our ways of life to address the human consequences. Atmospheric climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe, a prolific climate-writer and Professor of Political Science at Texas Tech University, provides a simple summary of the issue at hand in her chapter of the book All We Can Save, a compilation of essays by prominent female voices in the movement for climate justice. In her respective chapter, Hayhoe notes that “this isn’t about saving the planet—the planet itself will survive. The real question is—what will happen to the rest of us who live here?” (Johnson et al., 2021). What will happen to women will be predetermined by the social standing of women and the role of female leadership in formulating the next generation of climate adaptation policy responses.

What is Ecofeminism? Why Ecofeminist Policy?

Ecofeminism is a philosophy, and a potential policy lens, that explores connections between the unjustified domination and exploitation of women and nature. As a policy lens, ecofeminist policy analysis envisions alternatives to harmful male-biased views about women and nature (Warren, 2015). In this paper, I look specifically at climate-change related environmental risks and use climate change to express the application of this philosophical approach to climate-resilient policy design. Climate feminism may seem like a daunting policy approach; policymakers and activists have not achieved the goals of feminism, and we are failing miserably on many fronts to mitigate the impacts of anthropogenic climate change. How can we tackle both? Because these issues are deeply intertwined, and gender-blind policies merely perpetuate the status quo of gender-based violence. we must respond through an intersectional, ecofeminist policy framework that acknowledges their interconnectedness. Women will face disproportionate risks as the climate changes. Unless we design policies that uplift women from the patriarchal systems of domination that created our

Virginia Policy Review 15

current dilemma, policy responses will not foster gender equity. Gender-focused anti-poverty innovations and climate policy responses must be woven together as tightly as the problems themselves are. This paradigm shift in our approach to policy must start with a historical understanding of how we have learned to extract and exploit our natural environment, and how these cultural attitudes are mirrored in our treatment of women and girls. Western ideologies dating back to the Scientific Revolution inculcate a worldview that sees the domination of our natural world and extraction of her resources as the central aim of scientific and technological advancement (Warren, 2015). The use of “her” in this previous sentence is intentional; as much as we often view “Mother Earth” as a woman, this dominance orientation of man vs. nature is mirrored by the oppression of women by misogynistic social, cultural, and economic norms. The economic development made possible by the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions has resulted in many everyday luxuries, such as air conditioning and the fantastic selection of snacks at Trader Joe’s, but it has also resulted in the loss of natural ecosystems that previously served as both carbon sinks and flood buffers (Dahl, 1990). A carbon sink is a natural environment that sequesters carbon from the atmosphere; our economic mindset of “increase gross domestic product at all costs” has resulted in the destruction of these natural assets that could help us battle climate change. The National Fish and Wildlife Service (NFWS) conducted an audit of total wetland coverage in the United States from the 1780s to the 1980s, and found that, on average, over 60 acres of wetlands were lost every hour in the lower 48 states during that 200year timespan. In parallel to our profit-oriented extraction of resources and destruction of natural ecosystems, our male-dominated economic worldview often diminishes women to a subhuman status. We like to consider ourselves beyond this type of obstruction to opportunity in the United States. After all, we have female CEOs, and two of the sharks on Shark Tank are women, so many assume we have reached a point of gender neutrality. This is not the case.

Who Needs a Social Safety Net When We Have Women?

16 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a new layer of security risk and economic precariousness atop the already inequitable impact that climaterelated natural disasters have on women. As much as women are disproportionately harmed by natural disasters, women have also borne the brunt of the pandemic, with women of color faring the worst (Stevenson, 2021; Bauer et al, 2021). Female workers are disproportionately likely to be employed in customer-facing, low-wage service sector positions (Stevenson, 2021). Economist Betsy Stevenson describes this as a double-edged sword, in which women, predominantly women of color, experienced especially high rates of layoff or their jobs entailed increasingly dangerous conditions that exposed them to the virus (Stevenson, 2021). As childcare centers have shuttered their doors, women have also taken on the burden of non-market childcare labor, exacerbating pre-existing disparities in women’s role in unpaid caregiving. A recent analysis by feminist economist Dr. Lauren Bauer found that the majority of mothers (across essential workers, mothers working from home, and those not in the labor force) identified as performing all, much more, or somewhat more of the childcare duties within their household (Bauer et al., 2021). Racial inequalities amongst women have also been exacerbated by the pandemic; Black and Hispanic mothers experienced higher rates of unemployment than white mothers of young children, largely due to their high rates of employment in the service sector and vulnerable industries such as early childhood care (Bauer et al, 2021).

These are but a few examples of how our day-to-day economic systems can overburden women with non-market labor of childcare, eldercare, and other domestic work. When the social safety net falls short during times of crisis, women are forced to leave work (Diamond et al, 2021). More gender-inclusive policies such as paid family leave or fair wages for early childhood caregivers also tend to fall to the wayside as a result of patriarchal norms in our economic policy during times of crisis and normal market conditions; as a result, many low-income women are left vulnerable to the booms and busts of the market (Stevenson, 2021). These systems discourage women’s economic self-sufficiency and household financial stability in ways that make them more vulnerable when emergencies such as natural disasters strike.

Virginia Policy Review 17

Take, for example, the lived experiences of the women at the South Texas Border who have harvested the vegetables which kept our grocery stores stocked through the COVID-19 pandemic. These workers are paid $3 an hour and lack access to labor protections and collective bargaining due to fear of deportation (Sims & Cárdenas-Vento, 2019). The labor market is an especially inequitable space where women, especially women of color and low-income women, often lack the fair conditions and stable income necessary to envision a resilient future. These women are barely squeaking by as they live paycheck to paycheck in order to feed their families; it is unlikely that they have the time or the resources necessary to purchase flood insurance or think ahead to the consequences of severe drought for the Southwestern agricultural sector (Fernández-Toledo et al, 2020). When we remove hurdles to economic self-sufficiency and rebuke the constrictive social boxes of traditional gender roles, we disrupt these economic obstructions and allow women to unleash their potential (Jacobs & Bahn, 2019). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates that the pervasive influence of gender-based discrimination in our social institutions deprives the global economy of up to $12 trillion (Ferrant & Kolev, 2016). Gross domestic product (GDP) is often a poor measure for the thriving of our communities, but this number serves as evidence that when inequality runs rampant, we are missing out on global prosperity. This lost potential, the inevitable result of constructing barriers to economic security for half our world’s population, is entirely avoidable. OECD also projected that by gradually reducing discrimination in social institutions, we could increase the average annual world GDP growth rate (currently estimated at 0.03 percentage points) up to 0.6 percentage points by 2030 (Ferrant & Kolev, 2016). We must respond to the new challenge of climate injustice through an intersectional, ecofeminist policy framework that acknowledges the interconnectedness of environmental exploitation and gender-based oppression in our socioeconomic systems. Ecofeminism can help us to paint the first brush strokes in what must be a creative, inclusive policy framework for a resilient future.

From Gender-Based Economic Oppression and Environmental Injustice to Resilient Policy Design

18 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

Women’s security and economic security is under disproportionate threat as we prepare to fight the worst consequences of climate change (Neumayer and Plumper, 2007). Because women are the most at risk of harm, they are among the most critical players that must have a seat at the table as we grapple with potential policy solutions. One example of how giving women a seat at the table can foster resiliency is the case of Kitakyushu, Japan. The active role of women’s associations in the 1970s bolstered the city’s path to sustainable development as these associations raised concerns about health risks caused by the city’s industrial structure (Strumskyte, 2019). The women's groups pushed the city away from a focus on the steel industry and toward renewable energy and recycling industries. This transformative policy leadership is lauded by the United Nations Environmental Program as “one of the greatest environmental comeback stories of the 20th century” (United Nations Environmental Program, 2019). Through the leadership of women, Kitakyushu became Japan’s first “Eco Town,” rather than becoming yet another industrial wasteland. Indeed, Kitakyushu’s success on this front is now considered a model for other green cities. Limitations on women’s economic, social, and political prospects are socially constructed, and disrupting these cultural norms is critical to building a more equitable future. Likewise, our ability to ensure resilient coastal infrastructure in the face of climate change will depend on our willingness to disrupt the status quo; we must think beyond man-made flood mitigation infrastructure and embrace natural solutions. When we think of infrastructure, we often think of what many have deemed “gray” infrastructure: man-made roads, bridges, sea walls, pump stations, and other constructed structures. This infrastructure provides what it is designed to provide, but preserving natural ecosystems provides more far-ranging benefits—cleaner water, carbon sinks, and flood buffers to name but a few benefits.. But what exactly is green and natural infrastructure, and what distinguishes this infrastructure from simply leaving nature alone?

What is Green Infrastructure, and Is It More Than a Buzzword? Proof is in the Economic Pudding

Much like limiting women to the sphere of the home, limiting climate resilience policy to gray infrastructure solutions limits the effectiveness of our

Virginia Policy Review 19

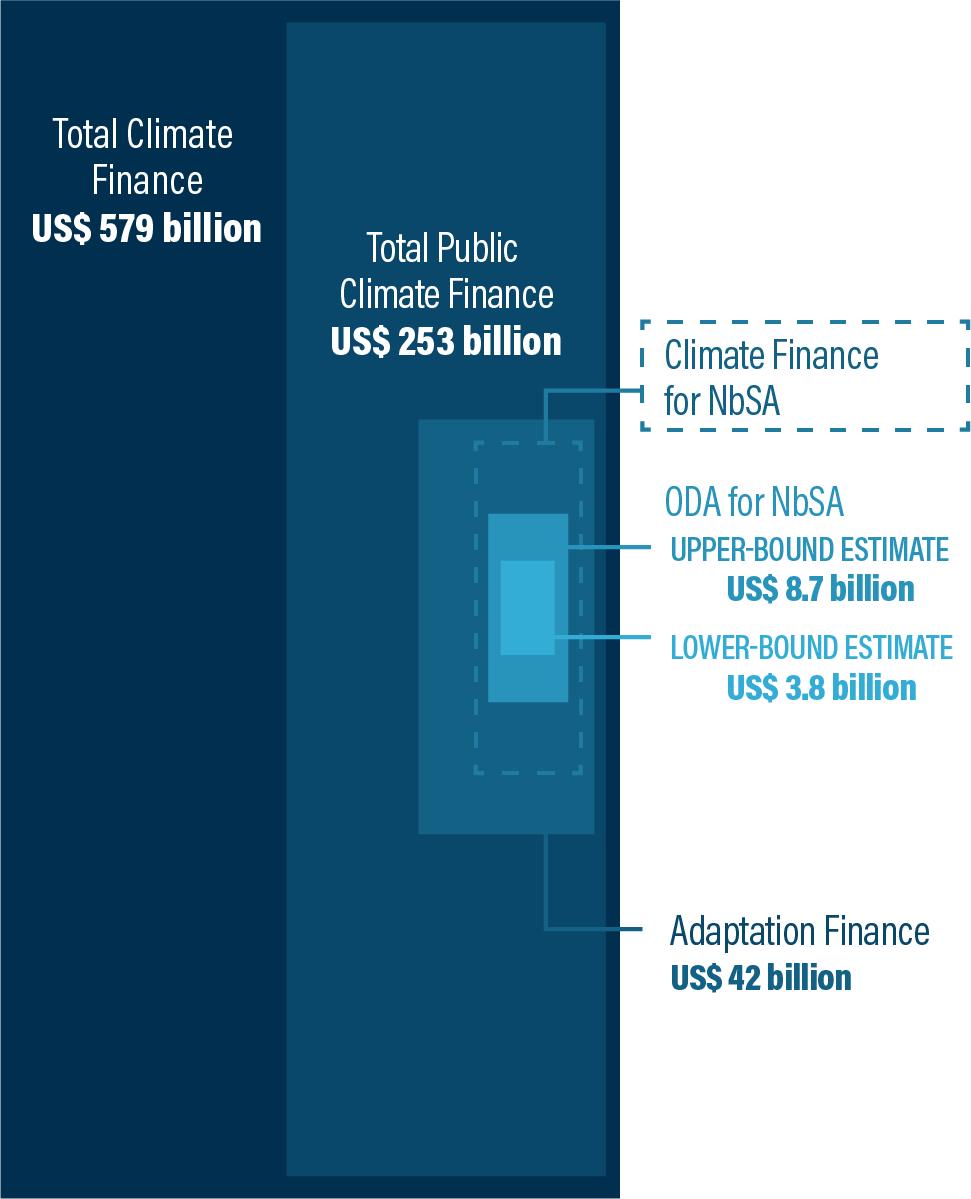

disaster-preparedness plans and ability to sequester enough carbon to prevent climate disaster. Restoring mangrove forests, a common nature-based solution that uses intentional land stewardship to address coastal flooding, is two- to five-times cheaper than conventional gray infrastructure such as artificially engineered breakwaters (Cook, 2020). Mangrove preservation could generate total net revenues of $1 trillion, but both ecologists and economists warn these cost-effective adaptation measures are currently underfunded and underutilized (Lieuw-Kie-Song et al, 2020; Bapna and Fuller, 2021). As illustrated in Figure 2 below, 2018 public finance for nature-based adaptation solutions was approximately 0.6% of total climate finance flows and 1.5% of public flows (Bapna and Fuller, 2021).

Figure 2: Source: Bapna and Fuller, 2021

20 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

Nature-based solutions and green infrastructure can range from strategic land management and lower-impact development all the way to the multidimensional, innovative “Engineering with Nature” projects initiated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers which combine green and gray approaches (U.S Army Corps of Engineers, 2021). The term green infrastructuretypically refers to stormwater management systems that mimic nature by soaking up and storing water away, such as permeable pavements, tree trenches, and green streets (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2021). In contrast, natural infrastructuredescribes the active management and conservation of landscapes that serve as storm buffers and carbon sinks (The Nature Conservancy, 2021). Managed wetlands are an example of natural infrastructure; through swamp lands, Mother Nature provides a natural sponge that can filter, absorb, and slow excess runoff. Augmenting this natural sponge effect through land conservation, such as through managing water levels and cleaning out plant growth, can further enhance water quality and flood storage benefits (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2021). These approaches can overlap and work in harmony with each other, and they offer advantages and applicability in different policy contexts. Building a resilient future and protecting our most vulnerable neighbors from climate catastrophe requires more than merely altering building codes and raising a few bridges; we must seek creative and inclusive solutions, drawing knowledge and ideas from the women that are and will be most impacted by climate change. In the case of coastal resilience, this starts with acknowledging the economic, social, and ecological value of nature-based solutions outweighs the public cost-benefit ratio produced by implementing gray infrastructure solutions alone (Bapna and Fuller, 2021). Nature-based solutions such as wetland and coral reef conservation raise society’s “triple bottom line” through environmental, social, and economic co-benefits (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2021). The superpowers of nature-based solutions are many, including reduced flood losses and stormwater management costs, improved water and air quality, increased property values and a higher tax base, benefits for private and commercial property owners, and green jobs in local communities (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2021).

Virginia Policy Review 21

The U.S Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) projects that annual damages from flooding will increase by $750 million by 2100 (EPA, 2021). Nature-based solutions are a highly cost-effective flood mitigation strategy (Bapna and Fuller, 2021). One study finds that every $1 spent to restore wetlands and reefs produces $7 of direct flood reduction benefits (The Nature Conservancy, 2021). The payoffs are real for “rewilding” policy efforts; Vietnam’s $9 million investment to restore 9,000 hectares of mangroves produced $15 million in avoided damage to private property and public infrastructure (Browder et al., 2019). Do we pay now to conserve these undeveloped areas, or allow development to proceed and pay for the damages as climate change takes its toll? Researchers at the Nature Conservancy dove into this question by identifying an area of “100-year” floodplains where conservation would be an economically sound way to avoid flood damages as climate impact accelerates. For over 21,000 square miles of the studied area, the benefits of conservation were at least five times the cost; every dollar invested in floodplain protection today produces $5 in future returns, recouped through avoiding catastrophic flood damages (The Nature Conservancy, 2021).

The answer is clear; it is more economically, socially, and environmentally wise to preserve our wetlands, marshlands, and other flood-buffering areas now.

Hence, developing green spaces is more effective than traditional gray infrastructure in many circumstances, particularly once we account for the triple bottom line Return on Investment (ROI) implied by social and ecological cobenefits for local communities. Economic benefits abound; the use of green infrastructure like waterfront parks or greenways may raise local property values and improve the tax base in both high-growth and low-growth areas (Georgetown Climate, 2021). Though at first glance this seems to be gentrification in disguise, when utilized in conjunction with meaningful investments in community revitalization, these investments can mitigate risk in flood-prone areas while stabilizing property values in high-vacancy areas (Georgetown Climate, 2021; Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2021).

22 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

Ecological benefits include the natural filtration of plants leading to better water quality and air quality, healthier habitats, and the additional carbon sequestration that gray infrastructure simply does not provide. Social benefits (defined as direct human benefits in local communities) include cooler localized temperatures, which is particularly important as women and people of color face disparate impacts of urban heat islands and are more likely to face harmful health impacts of heat waves (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2021). New green spaces also provide much needed outdoor recreational benefits, and greenways can even provide active transportation alternatives for urbanites. Until we can phase-out gas guzzling vehicles for electric vehicles with no tailpipe emissions, finding ways to integrate green streets where they do not exist and improve connectivity might incentivize us to substitute our feet and bikes for our CO₂ emitting transport options.

Nevertheless, advancing these nature-based solutions with gender neutrality is not enough. We must empower female leadership and allocate funding in equitable ways to ensure these projects are inclusive of marginalized communities. Capital for this type of adaptation project is soon to flood into the pockets of localities from the federal government.

A Flood of Funds: BIF Provides the Capital, But Will Not Be Equitable by Default

A deluge of funds has already been allocated towards flood mitigation infrastructure via the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the $1 trillion “Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework” (BIF) signed into law by President Biden in November 2021 (Curtin et al, 2021). New funding streams can empower communities to think beyond gray infrastructure and advance ecofeminist principles throughout coastal resilience policy implementation. However, it is critical to note that whether funds are set aside for the types of resilient infrastructure projects that will advance gender equity in climate preparedness is largely left to the discretion of state and local policymakers (Martin et al, 2021). The devil is in the details, or more accurately, the impact of this policy on the women at the highest risk of climate disaster depends on the policy’s implementation and who is granted a seat at the table for determining which projects receive funding.

Virginia Policy Review 23

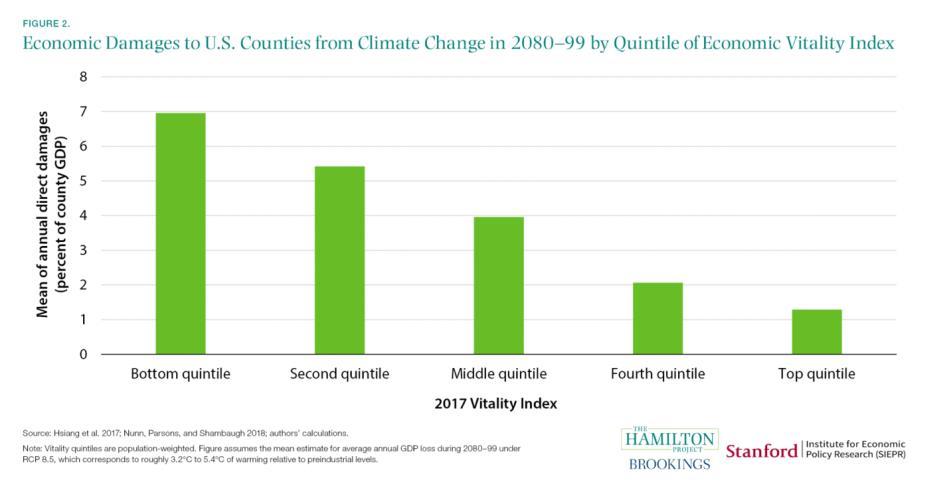

Brookings Metro scholars Carlos Martín, Andre M. Perry, and Anthony Barr argue that equitable allocation of BIF’s capital investments is not necessarily built into the new law (Martin et al, 2021). Further, they show how federal infrastructure outlays preceding the new Bipartisan Law have historically led to the fragmentation of Black neighborhoods through interstate highways, rather than delivering tangible benefits to them. Economically disadvantaged communities may also be left behind as capital is allocated. Localities which already face poor economic conditions will be among those hit hardest; socioeconomically disadvantaged women in these areas may benefit most from both green jobs and robust climate adaptation investments. Women living in the U.S. Counties scoring lowest on an “economic vitality index” (based on data such as labor market conditions and income levels) also reside in the areas of the U.S. which will be most vulnerable to the economic damages inflicted by climate change (Nunn et al, 2019). Figure 3 illustrates a projection that utilizes a summary measure of county economic vitality, paired with county level climate-related costs as a share of GDP projected by Hsiang et al. (2017). The findings indicate that “the bottom fifth of counties ranked by economic vitality will experience the largest damages, with the bottom quintile of counties facing losses equal in value to nearly 7 percent of GDP in 2080–99 under the RCP 8.5 scenario” (Nunn et al, 2019).

Figure 3

24 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

President Biden recognized that investments must be channeled towards our nation’s most climate-vulnerable citizens; he signed what some have coined a “Justice40'' executive order, which mandates that 40 percent of overall benefits from relevant investments be directed towards disadvantaged communities (Young et al, 2021). However, it is not the thought that counts; Martin and colleagues point out that this executive action is merely an administrative rule and not the law (Martin et al, 2021). Until real capital is committed to carrying out this priority and localities carry out this goal, it will continue to be lip service. Ensuring equitable policy design at the national and local level is a critical next step to ensure BIF investments translate into equitable infrastructure development. The following four policy ideas can help advance a more equitable economy and coastal resilience simultaneously.

1. States and Localities Must Set Aside a Portion of Funds from the

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act to Benefit Women and

Marginalized Communities

The BIF allocated $3.5 billion towards the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Flood Mitigation Assistance Program (FMAP), which provides financial and technical assistance to states and communities to reduce flood risk through elevation, buyouts, and other interventions (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2018). However, one of the bill’s major failures is the lack of targeted and transparent earmarks for disadvantaged regions (Martin et al, 2021). This could be overcome through applying Martin and colleagues’ proposal to refine the design of competitive federal grant programs like the FMAP. State and local budget policies can address equity concerns by setting aside a certain dollar amount or number of projects to serve flood-vulnerable communities with high concentrations of women of color. This ensures that the jobs created by green infrastructure and nature-based land management projects are designed to accrue substantial co-benefits to local women and minorities. Additionally, we must acknowledge that many historically underserved communities may not have the capacity to plan and execute this type of green infrastructure or conservation project (Martin et al, 2021). Hence, technical assistance must be equitably provided to ensure that the localities which will benefit most from flood protection have the capacity for resilient community development in the decades to come.

Virginia Policy Review 25

2. Incentivize Green Infrastructure through FEMA’s Community

Rating System: Finance Projects in Harmony with Insurance

Programs and Increase Access for Low-Income Women

The National Flood Insurance Fund (NFIP) uses a Community Rating System (CRS) to provide creditable flood insurance savings for communities (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2018). This means that communities who choose to implement certain flood mitigation measures, including naturebased solutions to buffer storm surges, are eligible for FEMA’s discounts that lower the cost of flood insurance for their residents. Natural flood-mitigation solutions can be counted towards the CRS to reduce insurance premiums for local NFIP policyholders (FEMA, 2018). These solutions are already cost-effective, but also can be used in harmony with insurance systems to mitigate risk; one study found that through integrating insurance reform with a reef restoration project, 44 percent of initial costs would be covered just by insurance premium reductions in the first five years, with total benefits amounting to over six times the total costs over 25 years (Regueruo et al, 2019). FEMA could make nature-based solutions for floodplain management worth more CRS points in the NFIP community rating system, providing a larger nudge for communities to implement green infrastructure measures. FEMA should encourage more women and lowincome households to partake in the NFIP program, as evidence suggests that flood insurance is unaffordable for most vulnerable, low-income households (Sarmiento & Miller, 2006). Targeted subsidies or tax credits for low-income individuals and households can help boost uptake of the NFIP program if the worst-case climate scenario does happen, despite nature-based flood mitigation efforts (Congressional Research Service, 2021). Reducing rates through nature-based solutions already increases financial accessibility and provides flood mitigation benefits but could be stretched further by accompanying community reductions with additional means-tested supports to ensure coverage for vulnerable communities.

3. Green Jobs Are Not Allocated Equitably Without Intentionality:

Equitable Workforce Development Policy Must Uplift and Give

Voice to Female and Marginalized Workers

Forest restoration is a highly labor-intensive policy priority which will require mobilizing the current farm and landscape labor force. But the direct economic benefit will accrue to those for whom the policy creates jobs, and

26 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

nature-based land management and green infrastructure jobs may not be accessible to women, particularly low-income women and women of color, without place-based workforce development opportunities (Harper-Anderson, 2012; McNeill, 2020). We can learn from past policy failures to understand how we can ensure that well paid, green jobs are accessible to all Americans, and especially communities of color and women. The research of Virginia Commonwealth University Professor and workforce development expert Elsie Harper-Anderson shows the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act failed to create many new green jobs for Black workers, who were disproportionately affected by the economic meltdown (Harper-Anderson, 2012). Anderson reported that “African American workers and businesses were systematically excluded from participating in and prospering from the resources offered due to their underrepresentation in many of the industries favored by the legislation” (McNeil, 2020). She expected a similar outcome after the COVID-19 recession and, so far, her predictions have held water. Without intentional focus on improving access to the skills and training necessary to participate in green infrastructure projects, history is likely to repeat itself as these industries grow (McNeil, 2020). Women should also be encouraged to seek out training and jobs in traditionally male-dominated fields related to the sustainable infrastructure and land management work necessary to bring these nature-based projects to fruition. Jobs in green infrastructure include landscaping and groundskeeping workers, farmworkers and laborers, construction laborers, maintenance workers, and more (Lieuw-Kie-Song et al, 2020). Women are underrepresented in many of these fields, forming only 5.3 percent of groundskeeping workers nationally (U.S. Department of Labor Women's Bureau, 2019). In other relevant fields such as agricultural work, women form a growing share of the current labor supply; women have climbed to 26.1 percent of the agricultural workforce as of 2019 (U.S Department of Agriculture ERS, 2020). However, it is entirely up to policymakers whether the green jobs and workforce development necessary to support resilience projects will include the women at the highest risk of displacement. Even in states like Texas, where women do hold a higher proportion of agricultural jobs (totaling 37% of the state’s agricultural workforce) many of these jobs are often held by migrant and undocumented women who are forced to work under exploitative contracts (Texas Department of Agriculture Statistics, 2021; Sims & Cárdenas-Vento, 2019). Many of the women working in the Rio Grande Valley in South Texas, near many flood-prone areas on the coast, pick cilantro under exploitative contracts for $3 an hour to feed their

Virginia Policy Review 27

children (Sims & Cárdenas-Vento, 2019, Guerra-Uribe, 2017). These workers lack access to labor protections and collective bargaining due to fear of deportation (Sims & Cárdenas-Vento, 2019). This infuses instability into the agricultural system; these workers can more easily be displaced by the consequences of climate change like super droughts and crop scarcity (Venkataramanan, 2020; McCarl, 2001). This fate is increasingly likely as climate change stacks the deck against these workers; some crops which Texas produces in great quantities may no longer be viable as climate change produces extreme seasonal drought conditions (McCarl, 2001). This century, Texas could face the driest conditions it has seen in the last 1,000 years, and seasonal weather changes will also result in variations in the projected yields and regional crop composition, posing a major risk if water supply strategies are not adjusted to prepare for this trend prediction (Fernández-Toledo et al, 2020; McCarl, 2001). However, policymakers can design a just transition that allows farmers like these migrant women of the Rio Grande Valley to find alternative employment in land management. This would also reduce the regional displacement and economic insecurity of migrant women (Sims & Cárdenas-Vento, 2019). Strategic upskilling and subsidies for green infrastructure projects might also allow female workers to transition into better paying, unionized land management jobs (Lieuw-Kie-Song et al, 2020). Pairing these policies with statewide enforcement of fair labor standards and collective bargaining rights would also foster resilience and allow them the economic security to get ahead of disasters. One model for coupling climate-fighting land stewardship with antipoverty policy that could uplift these women and their families is China’s Green for Grain program, the largest reforestation program in the world (Lieuw-KieSong et al, 2020). China allocates cash payments to rural households who reestablish forests, shrubs, and grasslands on land vulnerable to erosion. The program is part of China’s “emerging national poverty reduction strategy and resulted in a 12.8 percent yearly increase of household income for local farmers” (Lieuw-Kie-Song et al, 2020; Delang, 2018). This might be used in Texas to finance water supply preparation to ensure these women’s livelihoods aren’t at risk when megadroughts strike. These strategies can also combat multiple climate-related issues at once; for example, cash payments or tax-based incentives for farmers, particularly female and minority agricultural workers, could also be used to invest in agroforestry practices that can increase carbon sequestration while fighting rural poverty (UNEP, 2020; Delang, 2019). Agriculture-heavy states like Texas are also ripe for community investments in sustainable agroforestry; roughly 94

28 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

percent of forestland in Texas is privately owned, and thus up to individual’s discretion to manage and implement conservation practices (Texas A&M Forest Service, 2021; Natural Resources Conservation Service Texas, 2021). The state can invest in community-led management of common resources; tree-filled pastures can sequester five to 10 times more carbon than treeless areas of the same size, but this is currently an untapped carbon mitigation strategy. This agroforestry work is also far more labor-intensive than “conventional” monoculture, presenting green-job creation opportunities for women in agriculture. The same workers whose family’s livelihoods may be at risk due to seasonal droughts can also help advance a more resilient agricultural system on these cilantro fields, just a few miles inland of where coastal resiliency projects have the potential to protect coastal areas like Laguna Madre and Brownsville. Embracing land stewardship and rewilding efforts can lead us towards a more inclusive workforce strategy. We can fight climate change and give our nation's worst-treated laborers a fair shot at a resilient future.

4. Empower Female & Indigenous Leadership to Devise Collaborative Flood Mitigation Plans

Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland recently highlighted the importance of incorporating indigenous knowledge into climate policy at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Scotland (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2021). Haaland emphasized a critical aspect of the problem by saying, “If we are going to be successful in tackling climate change and addressing the biodiversity crisis, we have to empower the original stewards of the land” (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2021). This can be accomplished through ratcheting up efforts to center indigenous knowledge in the BidenHarris administration’s “America the Beautiful” initiative. This national effort seeks to conserve, connect, and restore 30 percent of our lands and waters by 2030 through voluntary, locally led action and community engagement with tribal nations. Managing our land in ways that foster resilience requires centering the knowledge and ways of tribal communities. One leading scholar in this field is indigenous scientist Robin Wall Kimmerer, a professor of environmental biology and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. In her book on indigenous knowledge, biology, and the power of nature, she notes that it is “not just the land that is broken, but more importantly, our relationship to the

Virginia Policy Review 29

land” (Kimmerer, 2016). According to Kimmerer, the process of becoming indigenous means “living as if your children's future mattered” and understanding the land as a gift (Kimmerer, 2016). As a nation of immigrants, she calls on us to become once again indigenous to our land by mending our toxic relationship with our natural environment and understanding the natural gifts we can reap from the earth we inherit. The administration's top priorities for the ambitious “America the Beautiful” initiative include “supporting Tribally led conservation and restoration priorities” and “expanding collaborative conservation of fish and wildlife habitats and corridors” (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2021). This effort must be linked to the recent funding allocated to the Flood Mitigation Assistance Program, and the $3.5 billion in BIF capital flows that could support it. FEMA’s flood response programs should link efforts with indigenous experts for practical floodplain management. Several indigenous communities consider water to be sacred with religious and cultural significance. Simultaneously, tribal communities face extreme vulnerability to climate-related flooding and other risks if we stay the current path (U.S Forest Service, 2016). Many tribal communities are not currently enrolled in the National Flood Insurance Program, and limited FEMA flood plain mapping on reservations may exacerbate this risk. Many indigenous communities lack access to information on climate risks and may not be able to purchase NFIP insurance (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2013). According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), increased data collection, insurance expansion, and the use of federal funds to leverage resiliency planning can promote resilience and reduce tribal flood vulnerability. Tribal communities are also intertwined with mainstream American infrastructural systems, and we will need to collaborate to ensure their resilience in the face of floods. Washington State’s policy response to the risks facing the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe provide one example of collaborative resiliency planning. This tribe uses Washington State Highway 101 as an access route for tribal goods and services (U.S Forest Service, 2016). This critical transport channel is threatened by sea-level rises, and the Jamestown S’Klallam have responded with an adaptation plan that includes “re-naturalizing floodplains, building roadside bioswales, and also working with the Washington Department

30 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

of Transportation to identify funding to elevate roads and bridges susceptible to flooding” (Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, 2013; U.S. Forest Service, 2016).

Conclusion

Equitable climate policy requires disrupting status-quo policy assumptions about gender and empowering female leaders, particularly those from marginalized backgrounds who are at the highest risk of climate-related displacement. Likewise, we need to cease attempts to out-maneuver and dominate our rapidly rising seas with gray infrastructure additions and instead find ways to augment natural processes. The economic evidence suggests that implementing gray infrastructure through raising sea walls and installing pump stations may not be the most costeffective approach, nor does it typically come with the many ecological, social, and health co-benefits which accompany green infrastructure (Bapna and Fuller, 2021). In embracing these natural solutions, we must center the needs and experiences of women to ensure policy design processes are both resilient and equitable. A resilient future is one where we learn to work across race, class, and gender to envision climate solutions that restore the co-benefits of Mother Earth. We must provide a robust social safety net for all families, especially those at risk of extreme weather events. We can choose to build more equitable economic systems that ensure women and their families have the financial stability to weather these storms, and we should envision a world where families can live without fear of climate displacement. An ecofeminist lens helps us work through these public problems in procedurally and substantively equitable ways. Let us unleash female leadership and nature’s potential to build a resilient future together.

Sophie is a second-year accelerated MPP candidate at the Batten School from McClean, Virginia. She graduated from the University of Virginia in 2021 with a BA in Political Philosophy, Policy, and Law and a minor in Economics. Her primary policy interests are education and labor policy, with a focus on advancing economic justice for low-income mothers and families. Sophie has interned and conducted research for The Hamilton Project, an economic policy initiative at the Brookings Institution. She is currently working with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Innovation and Early Learning.

Virginia Policy Review 31

References

Anastario, M., Shehab, N., & Lawry, L. (2009). Increased Gender-based Violence Among Women Internally Displaced in Mississippi 2 Years Post–Hurricane Katrina. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 3(1), 18-26. doi:10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181979c32 Bapna, M., & Fuller, P. (2021, March 22). Nature-based solutions for adaptation are underfunded - but offer big benefits. World Resources Institute. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.wri.org/insights/nature-based-solutions-adaptationare-underfunded-offer-big-benefits Bauer, L., Buckner, E., Estep, S., Moss, E., & Welch, M. (2021, September 29). 10 economic facts on how mothers spend their time. The Hamilton Project. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/10_economic_facts_on_how_mothe rs_spend_their_time Browder, G., Ozment, S., Rehberger Bescos, I., Gartner, T., & Lange, G.-M. (2019, March 21). Integrating green and gray. Open Knowledge Repository. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31430 Carvallo, J. P., Hsu, F. C., Shah, Z., & Taneja, J. (2021, September 20). Frozen out in

Texas: Blackouts and Inequity. The Rockefeller Foundation. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/case-study/frozen-out-intexas-blackouts-and-inequity/ Cook, J. (2020, May 21). 3 steps to scaling up nature-based solutions for climate adaptation. World Resources Institute. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.wri.org/insights/3-steps-scaling-nature-based-solutions-climateadaptation Congressional Research Service. (2021). Options for making the National Flood Insurance Program More Affordable. Congressional Research Service Reports. Retrieved February 14, 2022, from https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47000 in-texas/ Currie, J., & Rossin-Slater, M. (2013, February 12). Weathering the storm: Hurricanes and birth outcomes. Journal of Health Economics. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167629613000052 Curtin, T., Lukas, R., & Whitaker, A. (2021, December 18). House passes bipartisan infrastructure package, sends to president. National Governors Association. Retrieved

32 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

January 3, 2022, from https://www.nga.org/news/commentary/house-passesbipartisan-infrastructure-package/ Dahl, T. (1990). Wetlands loss since the Revolution - FWS. U.S Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.fws.gov/wetlands/Documents/Wetlands-Loss-Since-theRevolution.pdf Delang, C. (2019). The effects of China’s grain for Green Program on migration and remittance. Retrieved January 4, 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330209916_The_effects_of_China's _Grain_for_Green_program_on_migration_and_remittance Dellinger, H. (2021, February 24). Domestic violence shelters fight to keep survivors safe during

Texas Crisis. Houston Chronicle. Retrieved January 4, 2022, from https://www.houstonchronicle.com/news/houstontexas/houston/article/Domestic-violence-shelters-fight-to-keep-15963660.php Diamond, R. G., Spillar, K., & Shaw, S. (2021, May 7). Other countries have safety nets. The U.S. has mothers. Ms. Magazine. Retrieved February 14, 2022, from https://msmagazine.com/2021/03/01/marshall-plan-for-moms-feministcoronavirus-mothers/ Dunne, D. (2021, October 11). Mapped: How climate change disproportionately affects women's health. Carbon Brief. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.carbonbrief.org/mapped-how-climate-change-disproportionatelyaffects-womens-health Environmental Protection Agency. (2021). Manage Flood Risk. EPA. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.epa.gov/green-infrastructure/manage-floodrisk#:~:text=The%20average%20100%2Dyear%20floodplain,localized%20floo ds%20and%20riverine%20floods. US Department of Agriculture. Farm labor. USDA ERS - Farm Labor. (2020). Retrieved January 4, 2022, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farmeconomy/farm-labor/ Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2021). Building Community Resilience with nature-based ... - FEMA. FEMA RiskMAP. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_riskmap-naturebased-solutions-guide_2021.pdf Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2018) Community Rating System: A Local Official’s Guide to Saving Lives, Preventing Property Damage, and Reducing the Cost of

Virginia Policy Review 33

Flood Insurance. FEMA. (2018). Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_communityrating-system_local-guide-flood-insurance-2018.pdf Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2021) Infrastructure deal provides FEMA billions for Community Mitigation Investments. FEMA.gov. (2021). Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.fema.gov/press-release/20211115/infrastructuredeal-provides-fema-billions-community-mitigation-investments Fernández-Toledo, E., DeGood, K., Bergmann, M., Spitzer, E., & Simpson, E. (2020, June 26). The impacts of climate change and the Trump administration's anti-environmental agenda in Texas. Center for American Progress. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.americanprogress.org/article/impacts-climate-change-trumpadministrations-anti-environmental-agenda-texas/ Ferrant, G., & Kolev, A. (2016). The economic cost of gender-based discrimination in ... -

OECD. OECD. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.oecd.org/development/gender-development/SIGI_cost_final.pdf Georgetown Climate Center. Green Infrastructure Toolkit Introduction - Georgetown Climate

Center. georgetownclimatecenter.org. (2021). Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.georgetownclimate.org/adaptation/toolkits/green-infrastructuretoolkit/introduction.html?full Guerra Uribe, M. (2017). Flood risk areas in the Rio Grande Valley Colonias. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.caee.utexas.edu/prof/maidment/giswr2017/TermProject/FinalR eports/MonicaGuerraUribe.pdf Harper-Anderson, E. (2012). Exploring What Greening the Economy Means for African American Workers, Entrepreneurs, and Communities. Economic

Development Quarterly, 26(2), 162–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891242411431957 Jacobs, E., & Bahn, K. (2019, March 22). Women's History Month: U.S. Women's Labor

Force Participation. Equitable Growth. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://equitablegrowth.org/womens-history-month-u-s-womens-labor-forceparticipation/ Johnson, A. E., Wilkinson, K. K., & Hayhoe, K. (2021). How to Talk About Climate Change . In All we can save: Truth, Courage, & Solutions for the Climate Crisis. essay, One World. Kimmerer, R. W. (2016). Braiding Sweetgrass. Tantor Media, Inc.

34 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

Larrance, R., Anastario, M., & Lawry, L. (2007, March 30). Health status among internally displaced persons in Louisiana and Mississippi Travel trailer parks.

Annals of Emergency Medicine. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0196064406026199 Lieuw-Kie-Song , M., Pérez-Cirera, V., & Portugal Del Pino, D. (2020). Nature hires:

How nature-based solutions can power a green jobs recovery. International Labour Organization. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/ed_emp/documents/publication /wcms_757823.pdf Martín, C., Perry, A. M., & Barr, A. (2021, December 17). How equity isn't built into the infrastructure bill-and ways to fix it. Brookings. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2021/12/17/how-equity-isntbuilt-into-the-infrastructure-bill-and-ways-to-fix-it/ McCarl, B. A. (2001). Chapter 6: Climate Change and Texas Agriculture. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.530.1314&rep=re p1&type=/. McNeill, B. (2020). Study explores economic impact of covid-19, cares act on black workers and businesses in Virginia. VCU News. Retrieved January 4, 2022, from https://news.vcu.edu/article/Study_explores_economic_impact_of_COVID19 _CARES_Act_on_Black Natural Resources Conservation Service. Forestry | NRCS Texas. (2021). Retrieved February 14, 2022, from https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/tx/technical/landuse/fores try/ Nellemann, C., Verma, R., and Hislop, L. (eds). 2011. Women at the frontline of climate change: Gender risks and hopes. A Rapid Response Assessment. United Nations Environment Programme, GRID-Arendal. Neumayer, E., & Plümper, T. (2007). The gendered nature of natural disasters: The impact of catastrophic events on the gender gap in life expectancy, 1981–2002. Taylor & Francis. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2007.00563.x Nunn, R., O'Donnell, J., Shambaugh, J., Goulder, L. H., Kolstad, C. D., & Long, X. (2022, March 9). Ten facts about the economics of climate change and climate policy. Brookings. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from

Virginia Policy Review 35

https://www.brookings.edu/research/ten-facts-about-the-economics-ofclimate-change-and-climate-policy/ Pennsylvania Horticultural Society. Transforming vacant lots. Pennsylvania Horticultural Society. (2022). Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://phsonline.org/programs/transforming-vacant-land Reguero, B. G., Beck, M. W., Schmid, D., Stadtmüller, D., Raepple, J., Schüssele, S., & Pfliegner, K. (2019, November 14). Financing coastal resilience by combining nature-based risk reduction with insurance. Ecological Economics. Retrieved January 4, 2022, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0921800918315167 Sarmiento, C., & Miller, T. (2006). Costs and consequences of flooding and the impact of the

NFIP. FEMA. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/fema_nfip_eval-costs-andconsequences.pdf Shephard, C. (2021). Community incentives for nature-based Flood Solutions. The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.nature.org/enus/about-us/where-we-work/priority-landscapes/gulf-of-mexico/stories-inthe-gulf-of-mexico/community-rating-system-flood-risk/ Sims, S., & Cárdenas-Vento, V. (2019, July 10). Undocumented, vulnerable, scared: The women who pick your food for $3 an hour. The Guardian. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/jul/10/undocumentedwomen-farm-workers-texas-mexican Sparber, S. (2021, March 15). At least 57 people died in the Texas winter storm, mostly from hypothermia. The Texas Tribune. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.texastribune.org/2021/03/15/texas-winter-storm-deaths/. Stevenson, B. (2021, September 29). Women, work, and families: Recovering from the pandemic-induced recession. The Hamilton Project. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/women_work_and_families_recoveri ng_from_the_pandemic_induced_recession Strumskyte, S. (2019). Gender Equality and Sustainable Infrastructure - OECD. OECD Council on SDGs. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.oecd.org/gov/gender-mainstreaming/gender-equality-andsustainable-infrastructure-7-march-2019.pdf Texas A&M Forest Service. (2021). Manage forests and land. Retrieved February 14, 2022, from https://tfsweb.tamu.edu/content/landing.aspx?id=19856

36 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts. (2017). Natural Resources and mining overview women in the workforce. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://comptroller.texas.gov/economy/economic-data/women/miningoverview.php Texas Department of Agriculture Statistics. Texas AG Stats. Retrieved September 9, 2021, from https://www.texasagriculture.gov/About/TexasAgStats.aspx. Trenberth, K. E., Cheng, L., Jacobs, P., Zhang, Y., & Fasullo, J. (2018, May 22).

Hurricane Harvey links to Ocean Heat Content and Climate Change Adaptation. AGU Journals. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2018EF000825 The Nature Conservancy. Community incentives for nature-based Flood Solutions. The Nature Conservancy. (2017). Retrieved January 4, 2022, from https://www.nature.org/content/dam/tnc/nature/en/documents/CRS_broch ure-FEMA-CommunityRatingSystem.pdf The Nature Conservancy. (2020). Nature's potential to help reduce flood risks. The Nature Conservancy. (2020, January 28). Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.nature.org/en-us/what-we-do/our-priorities/tackle-climatechange/climate-change-stories/natures-potential-reduce-flood-risks/ United Nations Environment Programme. (2020). The Economics of Nature-based Solutions: Current Status and Future Priorities. United Nations Environment Programme Nairobi. United Nations Environmental Program. (2019). A Model City in Japan is helping Asian

Cities Go Green. UNEP. (2019). Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/model-city-japan-helping-asiancities-go-green United Nations Population Fund. Five ways climate change hurts women and girls. United Nations Population Fund. (2021). Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.unfpa.org/news/five-ways-climate-change-hurts-women-and-girls U.S Army Corps of Engineers. (2022). About EWN: Engineering With Nature. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://ewn.erdc.dren.mil/?page_id=7#details U.S. Department of the Interior. Biden-Harris Administration outlines "America the beautiful" initiative. U.S. Department of the Interior. (2021, October 7). Retrieved January 4, 2022, from https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/biden-harrisadministration-outlines-america-beautiful-initiative

Virginia Policy Review 37

U.S. Department of the Interior. Secretary Haaland focuses on indigenous led, nature-based solutions to climate change in Glasgow. U.S. Department of the Interior. (2021, November 8). Retrieved January 4, 2022, from https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/secretary-haaland-focuses-indigenous-lednature-based-solutions-climate-change-glasgow U.S Environmental Protection Agency. (2016). What climate change means for Texas. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-09/documents/climatechange-tx.pdf U.S Forest Service. (2016). Climate change and indigenous peoples: A Synthesis of Current

Impacts and Experiences. United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved January 4, 2022, from https://www.fs.fed.us/pnw/pubs/pnw_gtr944.pdf U.S Energy Information Administration. U.S. Energy Information Administration - EIA independent statistics and analysis. Texas - State Energy Profile Overview - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). (2019). Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.eia.gov/state/?sid=TX U.S Government Accountability Office. United States Government Accountability Office;

Participation of Indian Tribes in Federal and Private Programs. U.S GAO. (2013). Retrieved January 4, 2022, from https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-13-226.pdf Venkataramanan, M. (2020, July 27). Texas ranchers, activists and local officials are bracing for megadroughts brought by climate change. The Texas Tribune. Retrieved February 14, 2022, from https://www.texastribune.org/2020/07/27/texas-climatechange-megadroughts/ Walton, D., J. Arrighi, M.K. van Aalst, and M. Claudet (2021). The compound impact of extreme weather events and COVID-19. An update of the number of people affected and a look at the humanitarian implications in selected contexts. IFRC, Geneva. Warren, K. J. (2015, April 27). Feminist Environmental Philosophy. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/feminismenvironmental/#SecKinPosFemEnvEco Washington, J. (2021, September 1). Lessons from Texas: Advocates warn of Extreme Weather’s link to domestic violence. The Fuller Project. Retrieved September 9, 2021, from https://fullerproject.org/story/lessons-from-texas-advocates-warn-ofextreme-weathers-link-to-domestic-violence/.

38 Volume XV, Issue I, Spring 2022

Women's Bureau. (2019). Occupations with the smallest share of women workers. United States Department of Labor. Retrieved January 4, 2022, from https://www.dol.gov/agencies/wb/data/occupations/occupations-smallestshare-women-workers Young, S., Mallory, B., & McCarthy, G. (2021, July 20). The path to achieving justice40. The White House. Retrieved February 14, 2022, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/briefing-room/2021/07/20/the-path-toachieving-justice40/ Zurawski, K. (2018, October 16). Hurricane Harvey led to huge increase in family violence. Chron. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from https://www.chron.com/neighborhood/katy/news/article/KCM-Domesticviolence-increases-after-Harvey-13308826.php