written by Philip Polack

written by Philip Polack

The author of this short account, undertaken to celebrate the centenary of the Garden Committee in 1980, would like to thank those residents, past and present, and other friends who, by supplying him with information and documents, made the work possible, and his wife, whose encouragement helped him to finish it.

Cover illustration in pen and ink by Phoebe Bullock

2

© Philip Polack

CANYNGE SQUARE CLIFTON

A BRIEF HISTORY

PHILIP POLACK

“A beautiful Square - and none the worse for being a triangle”

W.R. Leadbetter, 1965

3

Looking from No.8 to Wellington House in the 1850s. Several things have now changed, as well as the size of the trees. (Reece Winstone).

4

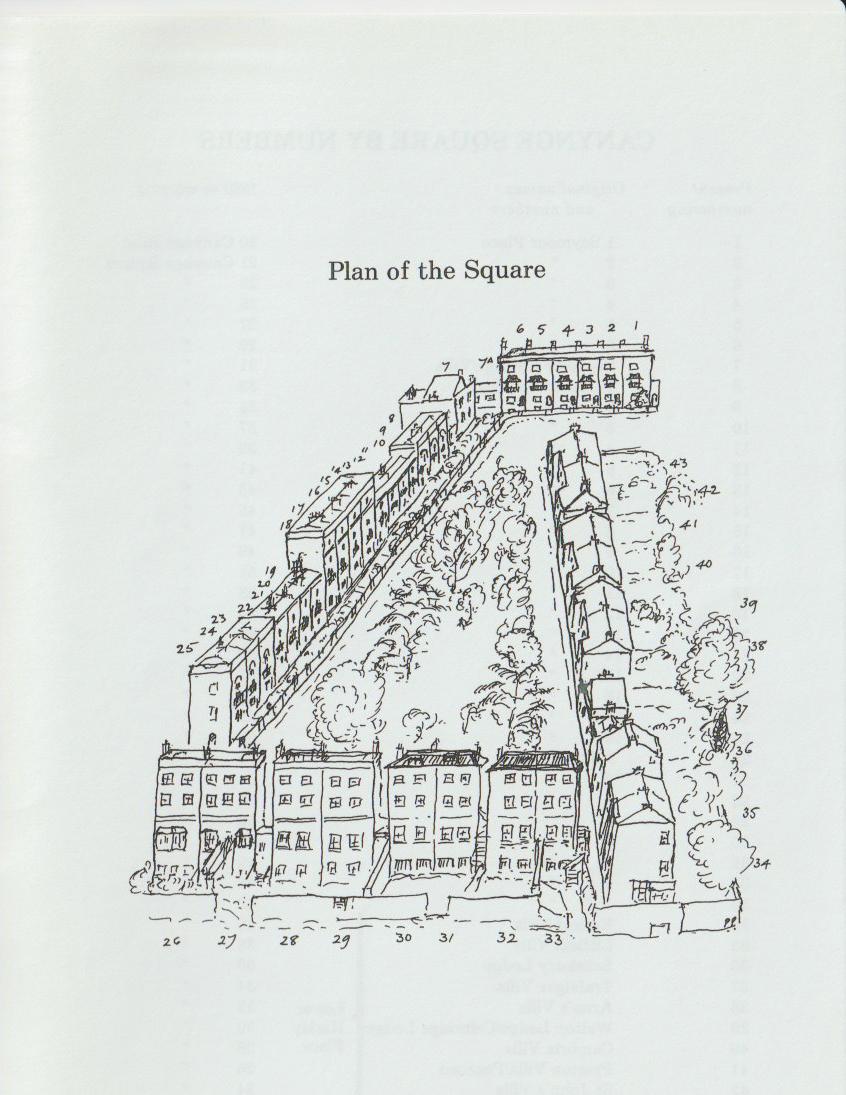

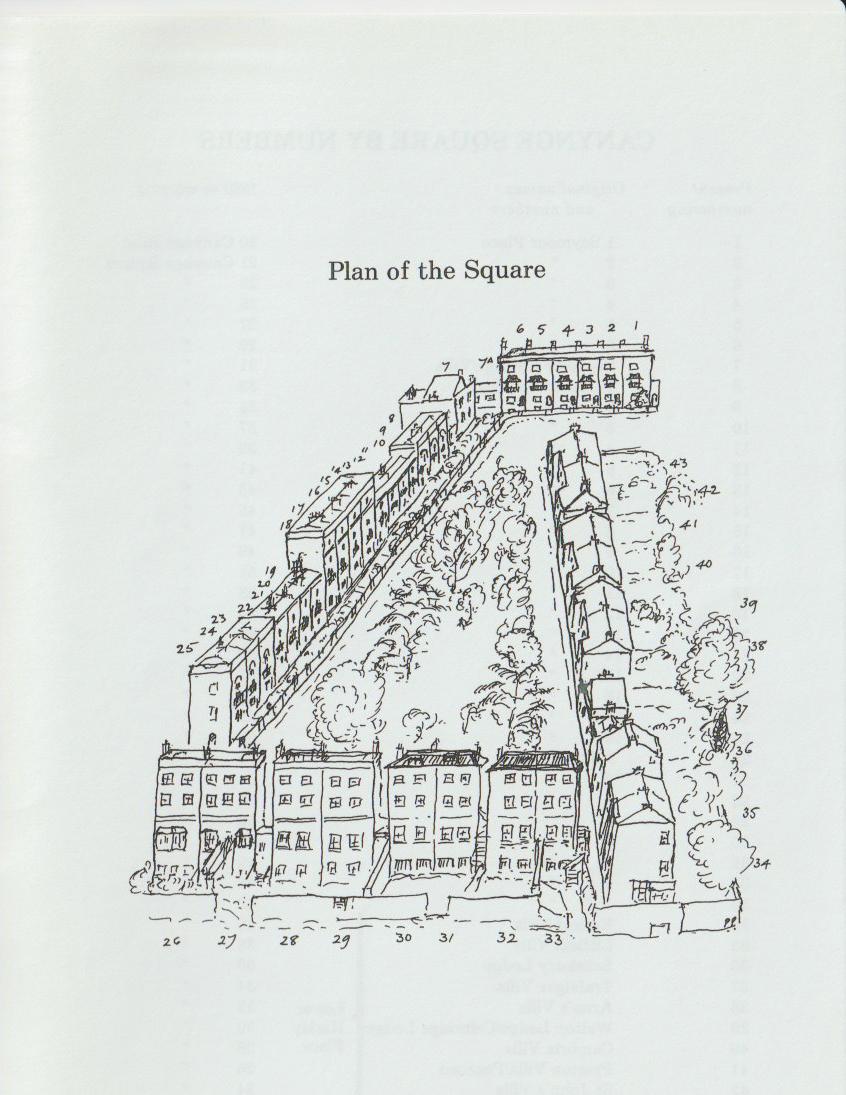

Contents Quiet homes and first beginnings 6 Squaring the triangle 16 The voices of children are heard on the green 21 The wear of winning (1) 25 Tennis, anyone? 26 The wear of winning (2) 31 Not rendering railing for railing; contrariwise blessing 34 Private faces in public places… public faces in private places 39 Laughter and the love of friends 47 Plan of the Square 50 Canynge Square by numbers 51 5

Quiet homes and first beginning (Hilaire Belloc)

The houses in Canynge Square were all built between 1842 and 1853 (or possibly 1857) and, with the exception of a few small alterations to attics and a sideways extension or two, they look very much the same today as they did then. They illustrate clearly what was happening to domestic urban architecture in the 1840s. Up to that time all town dwellers lived in terraces--unless they were rich enough to live in a large mansion standing in its own grounds (like Goldney House, Clifton Hill House, or Wellington House). By 1840 the small detached town house, the"villa"or"lodge", began to appear and was soon followed by a totally new development, the "semi-detached" house. All three kinds of dwelling can be seen in the Square. There are two kinds of terrace, one a succession of almost identical houses in a rather earlier style, the other planned as a whole like a French château, with central portion and wings; three solutions of the"villa"problem, one looking like a large house in reduced circumstances, one still pretending to be part of a rather grandiose terrace, the third perhaps beginning to develop a new style; and two quite different approaches to the"semi-detached'. It is interesting that the builders felt the need to mask the break with the terrace tradition by filling the gaps between the non-terrace houses with curtain walls and projecting porches, so that an impression of unity was given on the inward facing side.

The land on which the houses were built belonged to the Merchant Venturers, who owned altogether 565 acres in the Clifton area. A survey made in 1746 shows a farm leased to a Mr. Deverell, consisting of "a house, garden, orchard and five closes". The farm house was the present Harley cottage group and except for a small barn or outhouse just below the present entrance to Canynge Square, at the end of the garden of No. 42, there were no buildings to the north of it until you came to a cluster of small houses at the top of Blackboy Hill. Two "closes" known as "Littfields" ran from about the top of Norland Road round the Promenade (the ground between the farmhouse and these, now Harley Place, was known as Mr. Freeman’s freehold) and two, known as "Cecill's Littfields"' went down from "Somerset Place" but known from 1842 onwards as

6

behind the farmhouse to the line of Cecil Road, narrow at first and widening at the far end. A roadway ran between the farmhouse and MI. Freeman's freehold, on the line of Canynge Road, down to approximately the Wellington House site. By 1828 (Ashmead's map of North Bristol) this road was called Somerset Place and its extension Lower Harley Place. Somerset House (now replaced by Tyndal's offices) was built by then and so, on the other side, were Wellington House, Norland House, and the present Nos. 35 and 37 Canynge Road; these last three made up Lower Harley Place. There was an L-shaped building approached by, and lying across, what became Clifton Park Road- which turned eastward at this point across the present High School grounds. This building can be seen in photographs taken in the 1850s. Between it and the present line of 8-25 Canynge Square and extending southwards behind Somerset House, the 1828 map shows an enclosed area which could be an orchard or market garden, with a small square building behind (approximately) No. 13; the other small square building seen in the 1746 map is still there, on Lower Harley Place.

In October 1839 the "Master, Wardens and Commonalty of Merchant Venturers" made an absolute sale of 3 acres, 3 roods and 20 perches of the land known as Cecil's Littfields to Henry Daniel of 36 Clarges Street, Westminster and Edward Daniel the younger, of Windsor Terrace, Bristol. The price was £1500 plus a yearly rent of 40/- (Their right to make this sale was subsequently questioned in connection with Nos. 26-29 but their title to the land was affirmed in a declaration of 26 June 1855 by Cam Gyde Heaven, attorney and solicitor- who was also a mortgagee of the property-and the query was not taken further). Included in the sale was a "'message or tenement, garden, coach house, stable and premises”. Whether this referred to Somerset House or to the L-shaped premises mentioned above has not become clear.

At various times between May 1841 and January 1846 the Daniels sold the land in plots to prospective “developers”. These were mostly builders or relatives of builders, in conjunction with a gentleman" who provided the money. In all sales a "fee farm rent” e.g. £4.10.0 per annum from each of the houses (present 1-6) at the top of the square, £10 from each of those at the bottom (26-33), was

7

to be paid to Edward Daniel in trust for Henry, and later direct to Henry: the origin of the sums paid by present householders.

The first houses were 1-6, described in the 1841 indenture as “Somerset Place” but known from 1842 onwards as “Seymour Place". They were built by John M. Vanstone and George Evans, Carpenters, Builders and Undertakers of Canons' Marsh. They were required to erect 6 houses " with good and proper materials and in a workmanlike manner" by 22 May 1842 and to spend at least £450 on each house. Stone found on the site was to be used as far as possible, and "the front elevation and return end next the road” were to be faced, according to drawings which are almost identical with the present appearance of the houses, with cement, Bath stone and "stucco coloured (sic) and jointed to imitate freestone”. There were to be no windows on the east side of the end house. The front face of the roofs was to be slated, but the rest could be pantiles "coloured to imitate slate". The builder was to pay the architect three guineas per house but the architect's name has not come to light.

"Cambridge Place" (the present 8-25) named perhaps in honour of the visit to Clifton of HRH Duke of Cambridge in 1842, followed in stages: 1 and 2 (8, 9) were occupied by 1845, 3 to 9 by 1847, though the houses had probably been finished at least a year earlier. The plots for 8 and 9 for example were sold in June 1843 to George Jones, a St. George Carpenter, John Moulton, Carpenter and Richard Evans Cock, Mason, who were to build the houses by December 1844, make a carriage road, and pave the frontage, spending £500 on each. The architect of this interestingly designed terrace was Charles Underwood (fl. 1820-68) who had already designed 132-4 Queen's Road (on the corner of Richmond Park Road) and was later responsible for Promenade House (at the top of Percival Road), Worcester Terrace, Stoneleigh House (10-11 Clifton Park) the Chamber of Commerce building and the interior of the RWA, Queen's Road.

At the same time the "villas" were going up on the opposite side. There were originally to have been seven, called Hereford Villas, but this name does not appear to have been used. The address, after hesitation between Lower Somerset Place and Lower Harley Place,

8

settled as the latter (suggesting that perhaps some of the houses originally had their main entrance on Canynge Road). But they were never known by anything so vulgar as numbers. From 43 down the hill they were called Brighton Lodge, St. John's Villa, Preston Villa (Pencoed by 1880), Cambria Villa, Walton Lodge (Celbridge Lodge by 1879), Arno's Villa, Trafalgar Villa, Salisbury Lodge, Litfield Villa and Enfield Villa. Sale of the plots began in June 1842 and at least three of the villas were occupied by 1846. The last to be built was Salisbury Lodge (36): Ashmead's map of N. Bristol in 1846 shows the row filled except for this gap. Most of these villas were built by either George Evans and John M. Vanstone together or by Evans alone. The two had split up by 1844, Vanstone moving to 50 College Street (behind the present Council House). The two exceptions are obvious at a glance: Trafalgar Villa (37) was put up by John M. Kempster, boot-maker, of 18 Wellington Place (now Wellington Terrace) and his brother Isaac, builder, carpenter and undertaker of 4 Prince's Place (the west end of Princess Victoria Street), starting in 1842, and the plot for Salisbury Lodge was sold to them by Evans, who was beginning to overreach himself, in January 1846; the house or houses were to be built by March 1848. No mention of an architect has been found for any of the villas, but Evans employed one elsewhere in the Square and it is unlikely that Isaac Kempster could invent two such different designs as 36 and 37.

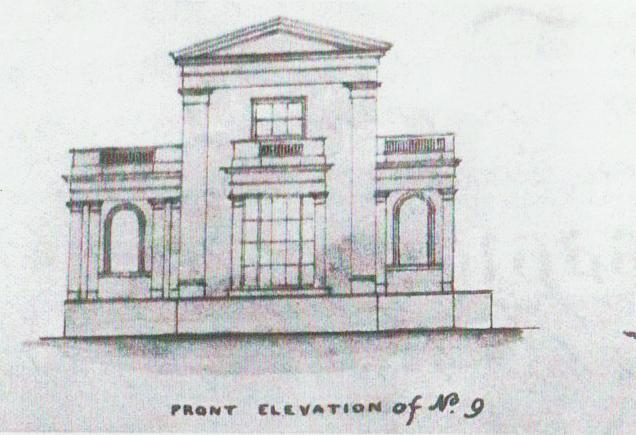

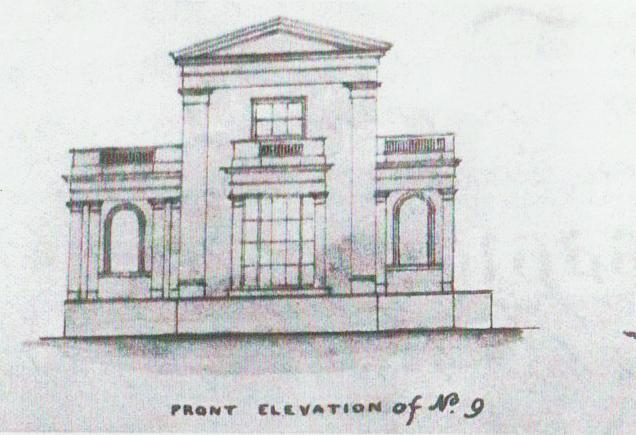

In October 1845 Evans, with a "gentleman" backer, had acquired from the Daniels eight plots along the bottom of the square “and also all that piece of or parcel of waste ground now a Quarry situate in the back of the said lots". He was required to build eight houses by June 1947, spending at least £600 on each. On the ninth, the Quarry, -the present garden--he was to "either erect one messuage or dwelling house… or otherwise convert the same into a shrubbery or other Ornamental piece of ground and in all respects under the inspection of Mr. Charles Underwood the architect and subject to the approval of the said Henry Daniel". On this house, if erected, he was to spend at least £400. A design exists for this “dream house”, a severe neo-classical little villa which might have been the most distinguished building in the Square- and would have robbed the other residents of a great deal of pleasure. Needless to say Evans did not take the first option. He did partly convert the waste ground into a shrubbery and he erected for at least had embarked by 1848

9

10

The painter Samuel Jackson, one of the first residents, sitting in his garden at 1 Cambridge Place (now No.8) with Francis Danny (1793-1861), a former member of the ‘Bristol School’ who had once given him lessons. The photograph was taken by Jackson’s son, S.P. Jackson, in the 1850s. (Reece Winstone).

on the erection of a house or receptacle for the preservation of ice… in, upon or under the said piece of water ground or shrubbery”. He confined himself to the eight plots which were not into be used or occupied as a Slaughter Floube Pig Stye Malting House or as a Hotel Tavern in Public House or House of Public Accommodation (sic)… or as a Shop of any kind") and did not take advantage of the option to build "a Stable and Coach house not over 9 feet high”; these presumably would have been in the gardens on the Percival Road side: "a Private road leading to... fields belonging to Francis Adams Esq.”

‘The house that never was’; the design for No.9 Albert Villas, to stand in what is now the bottom end of the garden.

Evans did not even complete the eight houses. He built the first four, 1-4 Albert Villas, (33-30) and up to the walls of the first floor of 5-8. Then, in 1847, he went bankrupt. Both the finished and the unfinished houses were bought for £2901 by Jane Daniel, widow (presumably of Edward) at an auction at the Bath Hotel, Clifton in 1848. After a further sale the unfinished ones passed to the firm of Messrs Fuller and Gingell, architects, in December 1850. This

11

partnership broke up shortly afterwards but the building was completed by the distinguished Gingell himself over the next three years.

William Bruce Gingell (1819-1899), one of the leading Bristol architects of the century, was an exponent, almost the inventor, of what Andor Gomme calls "Bankers' Italian and Warehouse Byzantine”. He was the winning competitor for the General Hospital (1853) and suspected of a little jobbery on his way to the prizedesigned what is now Lloyds Bank in Corn Street (1854), other banks, Nos. 33 and 36, in Corn Street in the 60s, and the Fish market, Baldwin Street two years before his death. To the more humble work of completing Albert Villas he gave close personal attention. He mortgaged the property to Cam Gyde Heaven and John Gyde Heaven and John Averay Jones and Charles Nash, Timber merchants, and contracted with Samuel Bowden, Builder (and carpenter, joiner and-inevitably-undertaker) of Redcross Street to complete the four houses for £3779, of which £2550 was to be loaned by the Heavens. A series of letters exists, from Gingell to the Heavens, asking for instalments to be paid to Samuel Bowden as he completed the various stages of the work. The final instalment of £550 on 19 November 1853 brought the total to £2350.

Gingell's detailed specifications for all involved may still be seen. They covered the work of the Excavator (even at this stage there was thought to be sufficient stone on site), Mason, Plasterer, Smith, Gas Fitter, Bell Hanger, Slater, Glazier, Plumber, Painter, Paperhangers, Carpenter and Joiner. Gingell left little to chance or the whim of the builder: in his instructions to the bell hanger it was laid down that there should be "a bell board over the door of the Housekeeper's Room in each House... one large bell with handsome brass sunk pull on the right-hand side of the front door with the word 'Visitors' cast on the upper margin in printed Capitals, One Bell with smaller brass sunk pull fixed below the preceding at the front entrance door, with the word 'Servants' cast on the upper margin in printed Capitals." Class distinctions were equally maintained in the matter of privies: the plumber was instructed to instal ‘Lambert's Patent WC acting by the seat' in the householders' privies, but the ones used by the servants had nothing of the kind; and while the main privies were lit by gas, those for the servants were to have a

12

small shelf to hold a candlestick. These were clearly handsome, well-appointed houses, even if not architecturally very distinguished.

The history of the remaining house, the present No. 7, is more complicated. The Daniels sold two triangular plots in the top corner to Vanstone and Evans in August 1842, when Seymour Place had been completed. On them they were to build, by June 1843, two semi-detached houses diagonally across the corner and standing well back, with the elevation, as regards height and materials, matching the terrace already built. By September 1843 they had not even started work. In that month they sold the plots for £2 to Odiarne Coates Lane of Somerset House, the garden of which adjoined the plate, and were them employed by him to do the building. The Daniels released Lane from the building conditions laid down. He was allowed to put up one house only; anywhere on the two plots, and the elevation dld not have to be uniform with the other house; it was to be completed by September 1845, under the supervision of Charles Underwood, and cost not less than £500, Lane first made the builders roughcast the blank caster wall of Seymour Place. He paid them in instalments as the building progressed and when it was finished he put his widowed mother inlaw, Mrs. Tremayne, into it at a rent of £40 a year, later raised to £60. It was known, to start with, as Seymour Cottage and after a few years, certainly by 1851, as Seymour Villa. When Mrs. Tremayne died in 1861 it was let for a couple of years to William Hooper, a retired Indian judge, and then, before the next tenant came - the Rev. Thomas Bowman, later headmaster of the Bishop's College, Bristol - Lane "added a storey" to the house (according to his widow's deposition of 1882). It is just possible that this storey was the bungalow at the side or the billiard room at the back, but this would be an unusual way of describing a lateral addition and it seems unlikely that a house the height of the present building could ever have been called a "cottage". More probably the new storey was added to the top of the existing house and the present façade dates from that time. Lane died in 1865, and in 1866 his widow occupied the villa, staying ten years; it was acting as a "dower house" for Somerset House.

A barrel-vaulted chamber and drain found underneath the garden of No. 7, and now sealed off, may predate the house. It may have been

13

part of an earlier building on the site, though none is marked on any known map, or of the outhouses belonging to the L-shaped house already mentioned. Or perhaps it was similar to other barrel vaulted cellars in the Square, below basement level (e.g. under the roadway at No. 37, with stalactites and stalagmites), which may have been "receptacles for the preservation of ice", like the one belonging to Albert Villas.

By the mid-fifties the as yet unnamed Square was complete. The occupants of all these houses in the early days were rarely the owner. The turnover of tenants was often rapid, but some of the original ones remained for over thirty years: a Mrs. Richards moved into Trafalgar Villa in 1846 and was still there in 1881. Moves within the Square started early: a Mrs. Russell was in 6 Seymour Place from 1844-6 and in Cambria Villa it 1847. They all have a fairly solid middle-class look about them: not "carriage folk" of course, but good class commerce with a sprinkling from the professions. The first recorded inhabitant was in 2 Seymour Place, John M'Arthur of Morgan, M'Arthur & Co Ironmonger & Iron Merchants, Charlotte Street, Queen Square. In 1845 Samuel Jackson, of the Bristol School of painters, moved from Freeland Place to 1 Cambridge Place (8) and lived there until his death in 1869. He is recorded as "drawing master", and by 1850 his son Samuel Jackson Junior is listed with him as "landscape & marine painter". It was the son who took the photographs of his father in the garden of No. 1 and of views from the house which can be seen in Reece Winstone's Bristol in the 1850s. In 1850 there was another drawing master, I. Brett, in 4 Seymour Place, a surgeon, C. Madden, in No. 5, and a dressmaker, a Mrs. Allen, in No. 2. A ‘merchant', Wm. Smith, lived in No. 1, and Cambridge Place had a Rev. Edward Wilson in No. 15, Sir Charles Macgregor at 18 and "Robert Young lodging house” in 7. A Captain George Woodfall lived in Preston Villa, sounding faintly like a Jane Austen character, forty years on.

It is not possible to say exactly when the various services reached the Square. Gas was available to the residents from the start: the Bristol Gas Co. had opened in 1816, using coal gas, and the Bristol & Clifton Oil Gas Co. in 1822, switching to coal gas in 1835 because of the rising price of oil. But street lighting and drainage did not arrive until some time in the fifties, following a damning report on the

14

city and environs by a Board of Health Inspector. There had been a cholera epidemic in 1849, in which 444 deaths were recorded in Bristol, and an inquiry was ordered. The inspector reported that there were no sanitary authorities in a number of districts, including Clifton, sewage gutters were uncovered even in middle class areas, cesspools often filtered into wells. "At Clifton Park, Cambridge Place... and in other high-class thoroughfares, there was no drainage except into cesspools". He concluded that the two great evils of Bristol, to which its drunkenness, filth and excessive mortality were largely attributable, were "want of drainage and want of water”.

As a result of this report, a Bill of 1851 gave the council, acting as a local Board of Health, jurisdiction over sewers, lighting, scavenging and watering. Among the first improvements were the street lighting in Clifton and the construction of sewers (beginning in 1855, after a cholera outbreak in 1854) to take the sewerage of the western suburbs into the Avon one mile below the Cumberland Basin.

Water may have arrived a little earlier. In 1841 Bristol was described as "worse supplied with water than any great city in England, and the whole city depended on a few local springs (e.g. Richmond Springs, Jacob's Wells). After an "expensive struggle” between the Merchant Venturers Company which wanted to tap further springs in the Clifton area, and a rival company which started in 1845 to bring in water from the Mendips, Parliament decided in favour of the latter scheme: Barrow water reached the city in October 1847 and by the summer of 1848 there was a reservoir on Durdham Down. But there are no records for the supplies to individual streets. In July 1880 the Clifton Chronicle carried an advertisement from a lady willing to "Lend her Furniture and Let her perfectly healthy, airy House in Canynge Square for 30s. per week… six Bed and three sitting rooms.” By then all was well, but it was still apparently necessary to say so.

15

Squaring the Triangle

In the Clifton Chronicle of 7 April 1880, Cyclops wrote in his weekly column "Seen with one eye": "I hear it is in contemplation to rename Seymour Place, Cambridge Place and Canynge Road ‘Canynge Square'. Surely this alteration is and is not problematical." He had a good chance of being right. As soon as 21 April the Chronicle included the newly named Canynge Square in its Directory section, but it might have been less of a problem if there had been more contemplation. The authorities attempted to number the Square or trapezium of buildings as if it were part of the recently-named Canynge Road (itself a creation from a composite past). 1 Seymour Place (our No. 1) became 20 Canynge Road, and the numbering then divided, the odd numbers of the Square, 21-67, going along Seymour Place and down Cambridge Place (our 2-25), the even numbers 22-56 running down Lower Harley Place and along Albert Villas (our 43-26)-more odd than even. The incorporation was halfhearted however, as the rest of Canynge Road was not renumbered and continued intermittently from 21 to 53. The confusion must have been considerable, matched only by the present Percival Road, but it lasted only a few years: in 1887 the Square was renumbered separately, exactly as it is today.

A more important consequence of the new-found identity was the formation of a committee to improve the "waste ground or shrubbery”. Gardens were in the air. Victoria Square, The Mall and Clifton Park had already been laid out and in June 1880 a Mr. Tovey of 2 Royal York Crescent wrote to the Chronicle of his discovery that the land in front of the Crescent was the common property of all residents (though used by some for growing their own vegetables) and suggested that it should be laid out for ornamental and recreational purposes. On 16 June 1880 six gentlemen (three of them residents of the Square, three presumably non-resident house owners) met in the house of Mr. Palmer, 35 Canynge Square (now No. 9) and decided to form a Committee to "improve the ground forming the centre of the Square". Mr. Palmer was elected secretary, and a week later, when the committee members brought estimates for fencing the ground with an iron railing, it was Mr. T.P. Palmer's (a relation?) which was accepted: 13/6 a yard and £3.5.0. for each

16

gate. Meetings followed at weekly intervals through June and July. Owners and occupiers were asked for subscriptions (sum not stated), a bank account was opened at Miles, Cave & Co., a stone wall was to be built round the area with stone extracted from the ground itself (Mr. T.P, Palmer paid the committee £6 for the stone and undertook to remove it in a week), Mr. Thorn(e) was to "fill the green" in six weeks (26 July to 4 September) for £10, and Messrs. Parker & Sons of St. Michael's Hill were to turf it for £60. By 23 October the filling and turfing were completed. Gratitude to the committee was expressed, with reservations, by Miss A.L. Fenton of St. John's Villa (No. 42) in her letter of 20 November to the Secretary and Treasurer:

Dear Sir,

The Central space in Canynge Square, being now enclosed to my satisfaction, and the ground levelled tolerably so, I hasten to send you as Secretary and Treasurer the sum of nineteen pounds, as my contribution to the work, less 40/- withheld, till the coping stones be cleansed from iron-mould.-(if ever) which (seems doubtful).

I congratulate you on the success of the undertaking. I quite dread however the obstruction which it is proposed to place in the road

The Square Garden, early on a summer morning; later in the day, a playground for children and a meeting place for parents. (Cedric Barker).

The Square Garden, early on a summer morning; later in the day, a playground for children and a meeting place for parents. (Cedric Barker).

17

in the shape of a lamp- Those only who drive know how inadequate even now, is the space afforded by the present unencumbered approach to the houses- The present lamp is now so well placed and burns so brightly, as it never did before its removal, that I shall be quite sorry not to let well alone- Please favour me with a stamped receipt acknowledge amount of enclosed cheque, and lest the funds may be too exhausted to provide a stamp, I venture to enclose one for your use.

Yours faithfully

AL. Fenton

(The offending gas lamp standard, by the way, stood in the middle of the road opposite No. 9 until the second world war.)

The committee then apparently rested from all the work which they had caused to be made: no further meeting is recorded for eight years and then-7 April 1888-only to discuss the clearing of snow from the "two crossings leading to the Pillar Post”. But there had been some unrecorded activity: seats already existed and had been removed from their rightful place: a meeting in May 1889 decided to nail a request to a tree, asking residents not to move them. Further, Messrs. Parker & Sons had been under contract to "keep the Square in order"; in December 1889 the committee decided to terminate the contract in March 1890, and sign a new one for the grass and paths and "keeping the Square in perfect order" with a Mr. Spenser who would also submit an estimate for gravelling the path. The railings were to be repainted for 3 guineas. At the beginning of March 1890 a tough letter was sent to Messrs. Parker & Sons, reminding them they had better complete the spring pruning of trees and bushes before their contract expired, or their account would not be paid. Unfortunately there is no record of the planting of these trees and bushes.

In April 1892-the next meeting-the gardener's salary was raised from £2.10.0 to £2.15.0 per quarter and the Bristol Sanitary Authority were written to because the watering and cleansing of the Square had been neglected. Thirteen years later, in May 1905, “Mr. Bennett submitted the accounts for the last nine years." The

18

The gas lamps (there are still four of them) have been retained by the pressure of a majority of residents. Since the 1940s the lamplighter has been replaced by the time switches, but maintenance is still necessary. (Cedric Barker)

19

financial position called for stern measures and a week later, 2 June 1905, the first General Meeting of residents took place, in Mr. J.H. Fowler's house, No. 16. Paths needed re-gravelling, they were told, and the coping stones of the borders needed resetting. To meet this, the annual subscription was fixed at 10/6, 7/6 and 5/- according to the size of house. Accounts were to be presented to the Committee annually on 31 March and a statement sent to each householder.

As far as is known there was no further General Meeting until 1966. Committee meetings continued at the rate of about one a year, except in moments of crisis, when they took place more frequently if the crisis was local, or sometimes, if it was national, not at all. The pattern of business became familiar: the Treasurer was accused of spending too much or of excessive economy"; gardeners were found unsatisfactory and were replaced; railings and seats (there were as many as five) needed repainting; trees had to be cut or up rooted, committee members were censured: 3 June 1910 "it was resolved… to regard as lapsed the election of Mr. Hayes in 1907, as he had never attended a meeting and had not paid any subscription since 1906". But around 1910, in the midst of this routine, a new presence began to make itself felt.

20

The voices of children are heard on the green

(William Blake)

There had been a school in the Square almost from the start: the Albert Villas school for boys, always known as "the A.V. school” (its badge was the two letters superimposed in light blue on a dark blue background). It was founded by Mr. W.R. Lucas who was in 1 Albert Villas (33) by 1854 and moved to No. 2 (32) in 1858. In 1880 he was running it with his daughters and by 1890 "the Misses Lucas" were in charge of it in 30 and 31, which had already become a single unit. It was a popular and well-patronised school: old pupils speak of it with affection and one of them remembers three Wills sons arriving every day from "over the Bridge" in a pony-trap at the turn of the century.

The pupils of the A. V. school were no problem to the residents in the Square. Contained in their walled playground at the back of 30 and 31- the bricked-up gate can still be seen in Percival Road- they were, like good Victorian children, scarcely seen or heard. But when the Canynge School was opened in No. 36, by Miss Magniac and Miss V. Goldfrap, the impact was considerable. The saga begins in June 1910 when a resident complained to the Committee about the noise made by the Canynge School children who were using the garden as a playground. Feeling was strong on the Committee that the garden should not be used as a playground: it had cost over £300 to make and build the garden "for the use of residents and to improve the frontage of the houses in the Square" and these objects were being frustrated. But there was a mole - fairly overt - on the Committee, Miss Caroline Mary Goldfrap - the family had lived in No. 28 since the 1860s - who thought the children should be allowed to use the garden as a playground, provided they did not make so much noise. It was pointed out that such noise was inevitable if "twenty children were allowed to romp together" and that, as non residents, the children had no claim to the use of the garden. A statesmanlike compromise was reached; the school could use the garden and the tennis court (the first indication of its existence in the minutes) provided that not more than six of them were in the Barden at the same time. The mole agreed to act as gobetween and convey this decision to the owners of the school.

21

Surprisingly soon, the Committee met again a month later. The Canynge School children were still using the garden regularly, the proprietors being "under the impression that the matter was in abeyance till another meeting of the Committee". (Miss C.M. Goldfrap's mole-like interpretation countered by the flexible convening of the committee!) Miss Magniac had written a few days earlier asking to be allowed the use of the garden for a 10 minute break every morning, for tennis and cricket with a soft ball for one hour on three days a week in the summer term and to "run in occasionally for a little fresh air in the morning but play no games” The Committee felt that the school had been using the garden a good deal more than that and that the main nuisance to residents came from children playing "at the narrow end of the Square" and not where the games playing went on. So they decided on financial sanctions: the school was to pay 7/6 a year for the morning break of ten minutes and 20/- in the summer term for the hour of games (this in addition to the ordinary subscriptions for No. 28 (Miss. V. Goldfrap's home) and No. 32 (Miss Magniac's). The narrow part at

22

The boys of the A.V. school, taken in the square c.1906. (by permission of Miss M. Richardson).

the south end was banned, no noise was to be made, times were to be strictly adhered to and any damage was to be paid for. Miss C.M. Goldfrap seconded this resolution.

At the next meeting on 26 May 1911, a letter from Miss Magniac, written that day, was read out: it stated that she and Miss V Goldfrap did not "think it right that they should be asked to pay for the past year". As the subscription had been asked for "as soon as possible" on 5 July 1910 and there had been two written requests since then, the Committee recorded "its astonishment at Miss Magniac's present repudiation of liability". Eventually she paid the 7/6 for the year, but not the 20/- for the summer of 1910- perhaps she had a point in view of the date of the decision; subsequent subscriptions were paid without complaint. But the children saw that they got their money's worth. In 1912 a resident complained of "the lack of consideration shown by those responsible for the children who use the garden" (though Miss Lucas' boys were a "marked exception and caused very little inconvenience") and the Hon. Treasurer added that the children of Canynge School had "raced over the beds and torn up the borders of stone”.

A year later, in December 1913, there was a complaint that “there had been a good deal of noise in the garden at the end of August” But this could hardly be blamed on the school and indeed no more is heard of Miss Magniac's children. The school moved to other premises and Miss Magniac herself flourished as a highly successful teacher until after the Second World War. Complaints about residents' children however continued from time to time and developed into a three-cornered contest between children (“wilful damage"), the Committee ("we should lock them out!" "No, no, we must influence parents to protect what is for the common good”) and parents. The response of parents is difficult to gauge, except on one remarkable occasion in the 1920s when the Hon. Treasurer received the following letter:

“…I am very glad indeed that you spoke sharply to L______ in fact I wish you had given him a good thrashing for I am sure he richly deserved it. He is the most wilfully lazy and disobedient child I have ever known, quite a different character from all the rest of the family. If he ever misbehaves himself again to your knowledge I

23

shall be very pleased if you will take the law into your own hands and deal with him in any way you may see fit. If you do that you will be doing him a good turn for perhaps it will make him realise his naughtiness if punished by a stranger. With many regrets that you should have been troubled by such a little good-fornothing ..."

Did the Committee feel it had influenced this parent in the right direction?

24

A family party in the Crichton’s garden at No.39, photographed in the early 1900spossibly, judging by the flag, at the time of Edward VII’s coronation. (by permission of Miss M. Ottery).

The wear of winning (1)

(Hilaire Belloc)

From the minutes of the Garden Committee:

5 January 1915: resolved "that Miss Ogilvie be appointed Hon. Treasurer during the absence of Mr. Burbey on military service”

23 May 1919: "As Major Burbey had now returned from military service he was asked to resume the post of Hon. Treasurer.

This is the sole reference to the 1914-1918 war in the records of the Square. (Major Burbey later commanded the O.T.C. at Clifton, where he was a master, and achieved fame through his order “All those who are parading without rifles-slope arms!"). The Committee was able to devote itself to the serious business of looking after the garden. In fact it met three times in 1915, a most unusual practice which perhaps accounts for the fact that attendance was poorrarely more than three at a time. A project for levelling the lawn had to be abandoned for lack of money, shrubs were bought. They tried to uproot "some old useless hawthorn trees" but only had enough money to take out one; and "it was decided not to cut down the fir tree which obscures the light in No. 20, being one of the few good trees we possess". The main preoccupation, however, appears to have been Woodman the gardener. He was engaged for one year in March 1915 at an annual salary of £8.10.0 "to keep the garden in thorough order" (extra work, e.g. remaking the rockery, levelling the lawn, to be paid for separately). In March 1916 he asked for a £2 rise, was told he couldn't have it and gave notice. But the Hon. Treasurer bought him off with a single donation of £1 and it continued at 28.10.0. In September 1917 his salary was raised to £20 10.0 on condition he looked after the paths as well- an early productivity deal. He resigned in July 1918. No new appointment was made and the Committee decided to rely on occasional help. The war was over and society had changed.

25

Tennis anyone?

(Humphrey Bogart)

In 1920 comes the first sign of a "do-it-yourself' approach to the gardening: Capt. G.. Green was elected to the Committee and thanked "for the work he put into the lawn and for repainting the garden seats". The tennis court~-whose existence up to now could be inferred only from the reference to Miss Maniac's school children--began to play a more prominent part. A subscription was fixed: 10/6 for one hour a week throughout the summer or 1 guinea for a two hour period; occasional use cost 1/- an hour. The periods were defined, running from 2.30-8.30 on weekdays only. Capt. Green collected the residents' preferences for bookings and there was a ballot after 1 May. Capt. Green decided when the courts were unit for play and posted a "No tennis" notice. (In an attempt to prevent children's "wilful damage” the Committee agreed that "No tennis” was to be interpreted as “No children to play games on the grass” but this still left them ample scope when the weather was dry.) Capt. Green also supervised the construction of a shed for the mower, tennis net and garden implemented and provided stone flooring for it. Judging by the minutes it was largely a “do-it-himself” approach. But there was some forced labour too: the boys of the A.V. Junior School were sometimes employed to weed the paths. And no doubt there was other anonymous help.

The tennis court was in continuous use until the end of the Second World War. Situated on the flattest, part of the garden, it was still not very flat and was not, according to contemporary accounts, of very high quality. It had no surrounding net, but the Square railingspermanently in need of painting- served as a sort of boundary on three sides. It would be nice to think that the court was a focal point for the social life of the Square, but apparently it did not work like that. It was in no sense a "club"; subscribers stuck to their booked times and played with their own friends, often from outside the Square.

The twenties saw some development in the Square's educational (establishments. One of the Lucas sisters who ran the A. V. school had married Mr. Frederic C. Webb. The other sister, Miss M.C. Lucas

26

had retired to the ground floor flat in No. 28; she was a natural leader with a great gift for keeping children happy and amused - she had spent thirteen years in Russia as companion in aristocratic families and continued to use these gifts, and others, with the children of friends in the Square. The Webbs took over the school in 1912.

They took a few boarders, mostly from army and colonial families, and there was plenty of physical activity: school walks on the Downs, swimming in the Victoria Baths (with boys learning by having to jump in at the deep end) and gymnastics on the premises. In the early 1920s a Junior School, for the 6-8 age, was opened in No. 8 under the Froebel-trained Miss Stanley and was noted for its creative approach to education: dancing, drama and manual skills played a large part.

In 1931 the Webbs sold the school and moved to No. 8, where their daughter Carmella lived until her death in 1979. Mr. F.A.B. Barnard, the new headmaster, made some improvements to the building and modernised the sanitation, but the school did not prosper. "Mr Barnard receives the sons of gentlemen between the ages of 5 and 14" says the prospectus. Perhaps there were not enough gentlemen left or perhaps their sons got a little out of hand: one of them remembers a riotous Christmas party when all the boys hurled sugar buns at one another; and another managed to draw on the wall beside his desk, apparently full-size, the complete controls of a steam railway engine cab. More probably it was the competition from Clifton College Preparatory School, newly established as a separate entity, that proved too strong, and the A.V. school closed, after eighty years of life, in 1933.

Meanwhile, around 1924, Miss Mortimer had started a kindergarten in No. 22 and ran this, with the two Miss Parkers as assistants, until well into the fifties. She had high standards and was a strict disciplinarian. She clashed occasionally with residents, and those on the western ("villas") side refused to let her use “their" pavement during the school's morning walks.

27

The interwar period as a whole brought a certain decline. "It had seen better days. That was evident in the delicate tracery of the fanlights over the doors and the wrought iron balconies breaking the Plain fronts here and there, but now most of the houses were in need of paint". This is E. H. Young's description of Chatterton Square (Cape 1947), set in 1938 and unmistakably based on Canynge Square in spite of a few disguises. One of the main characters rents a house, without a balcony, "in the left hand corner of the Square. It was in good repair and had an added though, he had to admit, an incongruous attraction in an extra, flat roofed room filling the space there had once been between his house and the one, at right angles to it, on the long side of the Square… This excrescence was ugly but its oddity was rather pleasing. It had the effect of being swung between the two houses for it was on a level with the pavement while they had their basements some feet below it and their first floor rooms a few feet above it." Clearly we are reading about No. 7, turned through 90 degrees, with its ballroom/ music room/ bungalow/dower house.

The novel deals with two very different families and the conflicts within and between them, and in the life of the Square it was indeed a period of contrasts and anomalies. The Garden Committee, for example, had a Treasurer and an Assistant Treasurer, its accounts were audited and its Annual Report was printed: yet its annual income was under £20 and Committee meetings were attended by five members or less. Clearly person or persons unnamed continued to look after the garden, but the Committee was often inactive. In 1928 the Chairman was asked to draw up a circular to be sent to residents with the report, pointing out that all users of the garden had an obligation to contribute to its support. A year later no circular had been sent so it was decided to use the ones that had been sent out in 1905. In 1932 there was no meeting "owing to illness” Between 1934 and 1938 no meetings were held and no explanations given.

There were other anomalies. The houses were not wired for electricity until about 1926 (there had been some shop and street lighting earlier), so it had been possible to listen in gaslit rooms to the wonders of wireless. Right up to 1939 the large department store of Jones in Wine Street, taken over much later by Debenhams,

28

made their deliveries in a high horse-drawn vehicle, painted black, with large rear wheels and smaller front ones, looking like a covered Wagon out of a western; while painted in gold letters on the sides, to the amusement of the children in the Square, was the inscription "Jones & Co., Bristol's Modern Store”.

The complicated chimneys of the paired Gingell houses were still being swept by dropping a cannon-ball down the opening: it could be heard bouncing its way down as it pulled its brush behind it.

In this confused period, along with the physical deterioration in the appearance of the houses, some of the old standards disappeared. It was no longer possible to divide the houses into “one servant households” - mainly on the east side - and "two-servant households" - mainly on the west. Conversion into flats, which had begun in some of the old Albert Villa houses early in the century, became more common after 1920. There was more coming and going: by 1939 residents in the houses along the bottom of the Square were used to being known as "the temporary people”. Rather more houses were described as "lodging houses” or "apartments", and some older residents may have felt the Square was going downhill. But if so, it was a gradual process. There had always been a lodging house or two-Robert Young in 1850, Mrs. Snook, widow of Joseph Snook, butcher, "the oldest established business in Clifton", in 1880-and there had always been a mixed society, with ministers of religion, violinists, tradesmen and "fly proprietors” (two in Nos. 3 and 4 in 1900) living happily side by side. But perhaps on the eve of the war it was a little more mixed than usual. On the one hand, in No. 6 lived Miss Codrington of the Doddington family, who had been a missionary to China with the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society. Caught in the Boxer Rising of 1900, she had received a sabre cut in the jaw - which left a blue scar - and had been left for dead under a pile of corpses, from which she was rescued by some of her converts. When new neighbours moved in next door, she sent them a courteous note asking them to respect the sabbath and play no music on Sunday afternoons when she conducted a Bible class. In the same terrace at the top of the Square, on the other hand, lived a hospitable lady who dispensed tea and sympathy to a variety of comers including, it is said, boys from a nearby school); her house became a Mecca for

29

American soldiers in the war and began, as Bristolians might have said and Joyce might have Willen, to bordel on the disorderly. She finally left the area and became a Matron at a distinguished Public School.

30

The wear of winning (2)

(Hilaire Belloc)

The second World War came much closer to the Square than the first had done. Yet the Garden Committee remained unaffected: at its only wartime meeting, in April 1940, it discussed the cutting and rolling of the tennis lawn, decided to postpone the repainting of the railings until a reserve fund had been accumulated-this proved to be a sensible decision- and agreed to lock the garden gates at night because plants had been stolen and cuttings taken. It did take a brief look at the war effort: it wondered whether to plant potatoes in the garden, but decided against it because the crop would be a small one owing to the lack of sun and "it would be an expensive matter to later replace the turf”.

The Blitz hit Bristol late in 1940. The ARP warden for the Square was Mr. Edward Colman of No. 34. Wardens had a bell to ring when aircraft were approaching and on one of his first sorties the clapper flew off his bell, leaving him "speechless"; as a member of the Magic Circle he must have felt that one of his best tricks had gone wrong. But there was soon more serious work for him.

Although there were no direct hits on the Square, bombs fell close enough and one or two incendiaries came through roofs. “Cook worked the stirrup pump," a housemaid said the day after, "I held the buckets, and the master sat on the stairs reading the directions." Miss Mary Ogilvie-who had acted as Treasurer of the Committee during the first War and was still Assistant Hon. Treasurer in 1940 at the age of 81-wrote her autobiography some ten years later: A Scottish Childhood and What Happened After (George Ronald, Oxford, 1952). Her account of the raids is worth quoting in full:

At first when the sirens sounded at night we brought our blankets downstairs to the dining-room, but this proved too tiring, and we soon learned to sleep through any bombing that might be Boing on. But on Sunday evening, November 24th, a terrific crash occurred. All the windows on one side of the house were smashed and the floors strewn with broken glass. We adjourned at once to our basement-kitchen where we remained till the 'all clear sounded

31

at 11.30. We then made some tea, filled our hot water bottles and went to bed. Next morning we swept up the broken glass, drew the curtains to keep out the draught and resigned ourselves to living for a few days, as we thought, in darkened rooms. Though it was sad to see pretty Norland Road in ruins, Park Street partly demolished, and so many churches now empty shells, that first experience brought, to my sister and me, a not unpleasant thrill and 'the joy of eventful living’.

I think it must have been in this blitz of November 24th that injury was done to the Bristol water supply which ran short for a day or two. To ease the situation an old well at the top of Canynge Road was re-opened, and it was an edifying spectacle to see a little crowd, some evidently from the top level, awaiting, jug or bucket in hand, their quota of the precious fluid. In the following week, on December 2nd, we had another raid worse than the previous one. Though aware one was in progress we sat down to our usual game of bridge before supper, well out of the way of splintered glass, when a nerve-wracking noise occurred. We instinctively ducked our heads-a futile proceedingand lost no time in making our way to the basement. Bombs whistled over and around us till nearly midnight and there we sat in darkness for the kitchen shutters had been torn off by the blast. We were not without our creature comforts for we had managed to secure an eiderdown and some blankets, and by the light of a torch we warmed up some milk and mince-pieces intended for a birthday treat. Our Czech cook, Margaret Sobel, always retired under the table with groans when she heard the whistle of a bomb. I cannot say I felt afraid for I did not feel that anything would happen to us. But I think the effect is cumulative, and I am sure I should be much more frightened now. We learned next day that a lady living a few doors away was killed and her grand-daughter injured by the effect of a bomb which fell outside her garden.

A whole era, as well as a remarkable personality, comes through in this passage. The lady killed was Mrs. Crichton, whose family had occupied No. 39 since the end of the last century. The house had been let during the thirties and Mrs. Crichton and her grand daughter had only just returned to it in the autumn of 1940 when the raids started. They moved their beds to the basement and spent the

32

evenings there. The explosion of 24 November shattered windows and brought down showers of plaster in the rooms they had just refurnished, but the one on 2 December fell just behind the house, shearing the first-floor balcony clean away and wrecking the lower storeys. Neighbours and ARP wardens worked to release Mrs. Crichton from beneath a fallen beam, Elizabeth was helped upstairs with a badly injured shoulder and several hours passed before an ambulance got through to them. Mrs. Crichton died during the night-an artery had been severed-but her granddaughter recovered after an operation.

The Popham family, sheltering in the basement of No. 26, described how the floor lifted under their feet, the ceiling fell above their heads and, when the noise and the floor subsided, they found themselves looking down a deep hole; silence was total except for the sound of a stream running fifteen feet below them in the cellar. This was the effect of the land-mine which demolished the College squash courts. Higher up in the same house, Mrs. Sandwith, an elderly botanist of some distinction, had decided to stay upstairs: should like to be nearer heaven if I am to be killed'. Next morning the two Miss Aubreys, old and bent, opposite in No. 25, admitted shamefacedly: "We spent the evening under our dining-room table. Not the way we would have chosen to spend an evening”.

Following this December raid, there was no water or electricity in the bottom houses and no glass in the windows. The residents from these were evacuated and some others left, but the raids in the neighbourhood stopped after April 1941 and normality and residents gradually returned. Communal life during the war revolved largely round fire-watching: the enthusiastic organiser was Mr. Wyatt, painter and decorator, of No. 16, and one present resident who firewatched with him was Miss Connolly, who first came to live in the Square in 1913. The Wyatts basement had a reinforced ceiling and was used as an air. raid shelter by people from other houses. The community spirit still showed when VE Day came: a tea-party was held in the garden in May 1945 and it is claimed that this was the first occasion on which residents from all sides of the Square actually spoke to one another. It was at this party that one of the aged Miss Aubreys, led out by her sister, is alleged to have said in a puzzled tone: "Ar, but what’ll un do with Kruger?"

33

Not rendering railing for railing; but contrariwise blessing

(1 Peter 3.9)

The end of the war found the Square without railings or gates, which had been taken away to be turned into Sten guns. The committee immediately decided-in April 1946- that their replacement would be impossibly expensive (the purchase of tennis equipment was ruled out for the same reason). Apart from the actual business of running the garden, almost all the Committee's concerns for the next 30 years were connected with this single unavoidable fact. In 1948 the Treasurer, Mr. H.V. Holmes, applied to the Regional Compensation Surveyor and a year later the sum of £18.5.0 was paid over for railings and gates together (enough perhaps for a couple of gates at that time). Mr. Holmes had offered his resignation for the first time in 1948 and continued to do so until it was accepted in 1957: he had by then been treasurer for 29 years, which is certainly a record in the annals of the Square.

The Committee's main task continued for some time to be the collection and allocation of funds for the care of the garden itself. The actual work was undertaken by various residents, who were often not members of the Committee, sometimes under the supervision of a curator who was, and sometimes with the help of a paid gardener. Shrubs, plants and equipment were frequently donated by residents and in 1959 the Committee purchased a Suffolk Punch motor mower. But problems of continuity and maintenance inevitably arose. Equipment was sometimes irresponsibly used and it was "always the same few” who did all the hard gardening work. In December 1965 the Committee, meeting after a two-year gap, decided it would be better to call for an increased subscription and employ a firm of contractors. This in turn produced a call from residents for a general meeting, which took place in November 1966 (the first since 1905) and decided in favour of employing a contractor to look after lawn, paths and hedges, while retaining a certain D-I-Y element in the matter of plants and trees. It was also decided that the general meeting should become annual, and this popular move led to an increase it the number of Committee meetings to an average of three a year.

34

Over the years a large part of the Committee's time was taken up with the problems of "enclosure" and the lack of it. The absence of railings and gates made access a pushover for dogs and much easier than it had been for children. The dogs dirtied the grass and the grass dirtied the children-though in fairness to the dogs it must be admitted that it was not so much the free-lance dogs that caused the trouble as the ones being "exercised" by their owners; the latter were urged at one point to take a bucket and spade with them on their walks. No solution was found to the problem of dogs (a suggested notice marked “Private" was not regarded as helpful), but the efforts to deal with children were various and new. The old policy of admonition and chastisement gave way to a more psychological approach of child-winning. It was hoped that a well-kept garden would produce well-behaved children and on one occasion it was proposed that "children should be interested and informed by circularising a letter on the 1st of Spring"; they might even be made useful by tidying the garden under parental supervision: “suitable children were to be approached. Another approach was the provision of entertainment for them: a climbing frame might divert them from harmful pursuits. But the Committee could never agree whether a frame was desirable or not; the safety question worried them, and soundings of all residents were inconclusive. And the suggestion of a sandpit had to be rejected on hygienic grounds - the dog problem cancelling out a possible solution to the children problem.

The lack of an enclosure affected children in another way: they could not only get into the garden more easily, they could rush out of it across the road at any number of points. Traffic had increased enormously: whereas before the war it was unusual to see more than three cars parked in the Square (and lights had to be kept on at night) and the first post-war car had to be towed in for lack of petrol, there was now a constant coming and going. Various ideas for dealing with the question were suggested to and by the Committee: putting up a "Slow" notice, making the Square a one-way road, asking the Council to make "sleeping policemen". All were investigated and all were found to be either impossible or more complicated than had been thought.

35

The Silver Jubilee, in 1977, and the Square Garden’s centenary celebrations, in 1980, provided opportunities for community feeling - and for dressing up. (Chris Curtis).

36

It seemed that the only answer was to make the Square boundary secure, and this occupied the Committee and residents on and off throughout the 30 odd post-war years. Filling in the gaps with beech began in 1948 and continued at various times. A pergola along the northern edge was put up in 1964. Two gates- on the long sides of the Square- were bought in 1965, but it was some time before they could be made to close properly on a spring and not "close on small fingers", But the owners of small fingers still found many ways of petting into the garden without using the gates at all. And for the third gate the Square had to wait until 1981 when one was presented in memory of James Martin OBE.

In 1967 it became known that disused railings could be purchased from British Rail at a very low price and this proved a tempting proposition. In the event it was turned down because of the large initial cost of installing the railings, and the permanent cost of maintenance (the previous records of the Committee were evidence of this), and attention reverted to hedges - beech rather than Beeching - as a means for making the Square safe.

The Committee, during the post-war period, was not totally occupied with railings, children, dogs and safety. On the amenity side the tree planting must be mentioned. In 1973 the Urban Arboriculturist offered his service and presented a Tree Report. He was impressed by the variety of existing treen, consisting of "29 different species, mostly exotic” and it is unfortunate that no record exists of the dates of planting. Following his recommendations, several old trees were removed in 1974 and nine new ones (also exotic) were planted. One of these - the tulip tree - was presented to the Square by C.H.I.S, and another - the Japanese Pocket handkerchief tree - by the BBC, for the Square's cooperation in allowing some of the filming of "The Changes" to take place there. During the same decade two seats were presented, in memory of Ned and Phyllis Scott. They replaced an earlier one commemorating E.D. Evans, who died in 1949.

It was at this earlier date, in order to decide whether the Committee was entitled to receive the government's compensation for the railings, that enquiries were made into the status and ownership of the garden. It was found that the legal owner of the land was a Mr.

37

G.D.B. Pope but that she had no legal obligation towards its upkeep. Nor had the householders any legal liability to keep the Barden in good order. The Committee therefore accepted the money with a clear conscience, but the feeling that the whole Garden Committee process was an act of charity benefiting an unknown and uninterested landowner nagged at some minds and led to enquiries about a possible takeover by the Corporation, The Town Clerk was approached in 1955 but his reply was evidently not considered satisfactory and the project was abandoned in 1956.

The question came up again after the Commons Registration Act of 1965. It became clear that to register the garden as a Town Green under the Act would have certain advantages: although it would mean the Council took over the ownership, its status as an open space would be safe-guarded and it could not be turned into a car park-which would in theory have been possible under its private ownership. The legal owner had no objection to the registration and when the Commons' Commissioner finally held a hearing, in March 1975, it was formally declared that the City Council owned the garden- and was therefore in theory responsible for its upkeep. The Committee however was anxious to keep control of the garden, in so far as its resources allowed, and the Council, happy perhaps to be partially relieved of its responsibility, gave its blessing to this compromise arrangement. If a major repair became necessary, the reconditioning of the parapet for example, and the Committee could not afford it, the Council would undertake to do it- in the same way land with the same speedy that it repairs pavements. This has not so far been put to the test, but the Council celebrated its new responsibility by supplying free a large number of plants for the garden.

38

Private faces in public places… Public faces in private places

(W.H. Auden)

Nobody really famous has ever lived in Canynge Square; nobody, at least, has yet earned a commemorative plaque. The nearest candidate would probably be that early resident Samuel Jackson the painter, who spent the last twenty-four years of his life in 1 Cambridge Place. But other names could no doubt be put forward: an interesting item for the agenda of a future A.G.M.

There is one near-by public place where a large number of residents, not necessarily wise or nice, have shown their private faces over the years: Clifton College. The first headmaster, John Percival, was for a short time the mortgagee of No. 37, but the first master to live in the Square was probably ST. Irwin. He lived in No. 18 for ten years or so from his appointment in 1876. An inspiring teacher of English, he also composed inscriptions for church monuments, including some in the cathedral, edited the letters of the poet T.B. Brown and' published an edition of John Earle's Microcosmographie. He was the uncle and later guardian of Margaret Irwin, the historical novelist. Considerably less inspiring as a teacher, J.H. ("Piggin") Fowler was the author of a number of English text books and school librarian. He lived much longer in the Square, in No. 16 from 1898 until his death in 1932, and was much more involved with its activities: he became Secretary and Treasurer in 1905 and Chairman in 1909, a post he occupied until his death.

For a year or so at the turn of the century Arthur H. Peppin lived at No. 38. He had been secretary to Sir George Grove (Dictionary of Music ...) before his appointment in 1896, and as Organist and Director of Music he laid the foundations of the school's musical tradition. He started music scholarships and orchestral concerts, and his influence extended to public school music in general. M.A. ("'Neddy") North lived briefly in No. 35 (1907-8) before becoming a housemaster. He was co-author of the standard Latin and Greek Prose books "North and Hillard". He was a lively and entertaining teacher, but his humour was less than kind (e.g. Q. "Why is the River Avon so dirty?" A. "Because the South Town boys wash in it.") and

39

his classroom practices would not be tolerated for an hour in a school today, at least not in a local authority one. He did not stay long in the Square - and not much longer as housemaster.

The Rev. H.H. Symonds was at Clifton for only three years and spent one of them (1911-12) at No. 42. During that time he was also a W.E.A. tutor. He was later a headmaster in Liverpool and wrote an engaging guide, Walking in the Lake District (1933). Major J.L. Burbey, mentioned earlier, lived in No. 37 from 1908 until he retired in 1930. For some years he was simultaneously head of Modern Languages and housemaster of South Town and he twice commanded the O.T.C. Ralph Octavius de Gex, known for his frighteningly formal dinner parties, was in No. 29 from 1912 to 1915; he later became head of the Junior School. Henry B. Mayor, a rather dishevelled classicist, lived in No. 43 with his two sisters, Flora and (inevitably) "Fauna", from 1906 until he became a housemaster. The list could go on indefinitely- in fact a housemaster from almost every house in the school has lived in the Square either before or after his term of office, and there have been many other assistant masters as well, including the courteous and picturesque Swiss C.A. Jaccard, who could be seem in the twenties and early thirties walking every morning from No. 41 to the steps down into Clissold's Plot (where the theatre stands) wearing hie mortar-board and gown.

Contact with public figures in the musical and theatrical worlds has chiefly been associated with two houses, No. 39 and No. 17. Ernest Crichton (it was his widow who was killed in the air raid in 1940) came to No.39 in 1897. Originally a chartered accountant, he grew dissatisfied with the work and bought a music shop in Bridge Street. Not a musician himself, except as a choral singer, he had a great love of music and married an organist and pianist who had been at the Royal College of Music. The business prospered and expanded: two shops replaced the first, one at 38 Regent Street and the other at The Great Piano House, 76 Park Street (where Mose Bros. is today). He supplied instruments, sheet music and piano tuning services to Clifton College, and later when he opened branches in Gloucester and Cheltenham, to Cheltenham College as well.

For more than twenty years, from about 1897 to 1920, he was the impresario of International Celebrity Concerts and lectures at the

40

Colton Hall. In his autograph albums the signatures and comments can be seen of-it seems--all the musical celebrities, as well as many of the explorers, of this period. Some of these were entertained and may have performed in his own home, though the music making there was mostly done by his wife and three daughters and their friends, notably the Meyers, a Danish couple who arrived at No. 38 in 1915. Certainly all his family were taken to the concerts as soon as they were old enough and introduced to the performers. The youngest daughter recalls going to her first concert, in 1915, to hear the Belgian violinist Ysaye, an Australian soprano known as Madame Stralia, and the great - and eccentric - Russian pianist Pachmann, noted for talking to himself as he played and for taking Violent dislikes to certain members of the audience. Pachmann laid his hands on the eight year old Anna's head and said "When you are an old, old woman you can tell your children and grandchildren that old Pachmann laid his hands on your head and gave you his blessing", At another concert he gave during the ’14-18 war, some of the many nurses in the audience dressed him up at the end as a Red Cross nurse and in that costume he went on playing encores until the attendants, tired of waiting, began to dismantle the piano, giving up only when they removed the keyboard.

A more blatant instance of wartime fervour occurred when Bristol's own contralto, Dame Clara Butt, draped her ample form in a Union Jack to sing "Land of Hope and Glory', But she was better than that and did not always play down to her audience. Her great wideranging voice used to fill the hall and dominate it, just as her signature, in letters an inch high, dominates the pages of the auto graph book-she sang and signed year after year-and the more modest signature of her partner and husband Robert Kennerley Rumford.

Other singers who came were Tetrazzini (1908) and Melba (1913). Blanche Marchesi, the French soprano, came in 1901, the year before her Covent Garden debut, and wrote in the book "Bristol air, Bristol public, Bristol applause, all this is delicious to Blanche Marchesi". Harry Plunket Greene, Old Cliftonian and co-dedicatee with Arthur Peppin of the school song Parry wrote for Clifton, was there in 1901. Albert Chevalier ("My old Dutch") came in 1898, Yvette Gilbert in 1905, and in 1910 Ivor Novello Davies (sic), some

41

years before, still a young man, he wrote "Keep the home fires burning'. Besides Pachmann, the pianists included Paderewski (1898 and 1902), the Hungarian Ernst von Dohnanyi (in 1899, at the very beginning of his career both as a pianist and composer), Backhaus (1913), Cortot (1920) and Moiseivitch; and the violinists, as well as Ysaye, included Kreisler (1895 and later), Pablo de Sarasate (1899), the Czech Jan Kubelik, father of the conductor Rafael, (in 1901, on the second concert tour of his life) and Albert Sammons (as leader of the London String Quartet, in 1916). The cellist Casals appeared, Hans Richter brought the Hall Orchestra in his first year (1897) as their conductor, and Arnold Dolmetsch with two members of his family, pioneers of authentic instruments", came in 1910.

Among the non-musicians were the explorers Peary, who reached the North Pole in 1909 (1910), Shackleton (1910) and Wilfred Grenfell of Labrador (1914). R. Kearton (Cherry Kearton presumably) lectured on photographing wild life in 1900 and, as an indication of how up-to-the-minute Bristol was in those days, John Foster Fraser talked about "The Russian Revolution" as early as March 1917.

What is impressive about the list of musicians is not just the famous names but to see how early in their careers many of them came to Bristol; as a concert agent Ernest Crichton must have bad considerable flair. He had many other interests too, notably the sea and sailing boats, real and model; his children were provided with a "Quarter deck"-a railed platform between two flowering trees at the bottom of their garden. Sadly, his business declined; he was gradually pushed out of it by a partner who was more interested in money than music and left Bristol in the thirties, returning just before his death in January 1940.

For the theatre we skip thirty years and go across the Square. During the years in the early seventies when Val May was Director at the Theatre Royal, a large number of well-known people stayed at No. 17 or came as visitors. Dame Sybil Thorndike stayed there when the theatre was about to close for alterations, J.B. Priestley and Jacquetta Hawkes came, Iris Murdoch and her husband John Bayley, and Sir Harold and Lady Wilson plus Lady Falkender. Other visitors connected with the stage included Jane Wenham, Alan

42

Bates, Anthony Shaffer, Susannah York, John Mills and his wife with Hayley Mills, Roy Boulting, Ian Richardson, Timothy West, Kate Nelligan, Sarah Kestelman, Peter O'Toole and Nigel Stock.

Isolated instances of interesting visitors include the controversial American architect Buckminster Fuller, designer of machines for living, who stayed in the Square during his term as visiting lecturer at the School of Architecture in the early sixties, and the septuagenarian Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén, president of the National Union of Cuban Writers and Artists, who attended a students' party at No. 37 in 1975.

As far as the arts are concerned, the outstanding achievement by a present-day resident is certainly the Arnolfini Gallery. Jeremy Rees (No. 20) started this on a shoestring in 1961, in a small back-room behind Roberts' bookshop in Triangle West. Dealing almost exclusively with the visual arts to begin with, it aimed at bringing to Bristol aspects of contemporary art not previously available here. The response was greater than had been dreamt of, and ever, tally support from the public and various "bodies" led to gradual expansion (music, ballet, films, books) and to three successive Moves, culminating in the present occupation of Bush House on Narrow Quay, where the Gallery enjoys an international reputation.

In recent years a few residents have reached the "public", general or specialised, through the books they have written. Marion Connock (No. Ta and, as a child, No. 7) wrote Treasure in the Dark and Meet Harriet in the late fifties and early sixties, followed by The Boy from Spain (1965), and has written two biographies, The Precious McKenzie Story (1975) and Nadia of Romania (1977). Richard Gregory, in No. 7 in the mid-seventies, has written The Intelligent Eye (1973), Concepts and Mechanisms of Perception (1974), Eye and Brain (1977) and Mind in Science (1981). Charles Hannam (No. 35) was co-author of Young Teachers and Reluctant Learners (1971) and The First Year of Teaching (1976) and author of Parents and Mentally Handicapped Children (1975) and two volumes of autobiography, A Boy in Your Situation (1977) and Almost an Englishman (1979). Mig Holder (No. 23) has written stories and poems for children: The Saturday Books (four of them) (1971), Jason and the Twins (1972), poetry in an anthology, Making Eden Grow

43

(1974) and Papa Panov's Special Day (1975). Three short books of local interest have been written by John Sansom (No. 22): Children's Bristol (1976), Bristol Impressions (1977) in association with the artist Frank Shipsides, and The Redcliffe Guide to Bristol (1983); and The Clifton Guide, which his press published in 1980, contains several photographs by Cedric Barker (in No. 13 from 1956 to 1982). John Steeds (No. 21) has written Introduction to Anisotropic Elasticity Theory of Dislocations (1973) on defects in materials, and Peter Steele, who lived first in No. 2 and then No. 38 in the late sixties and early seventies, wrote Two and Two Halves to Bhutan (1969), with illustrations by Phoebe Bullock (No. 3), and Doctor on Everest (1972) after taking part in the ill-fated international expedition. Derek Winterbottom (No. 7) has written The American Revolution (1972), Doctor Fry (1977), a study of a Victorian headmaster of Berkhamsted School, and The Vale of Clwvd (1982).

With or without an impact on the wider public, there have always been in the Square a number of varied and interesting private faces. For almost the first twenty years of this century there was Joseph Lawson in No. 7, "Professor of music, piano, organ etc, organist of St. Mary Redcliffe until 1907, who had his own organ in the “music room (No. 7a), then one undivided hall which was used for choir practices and dancing classes. For more than forty years from 1913, Mrs. Sandwith lived in the top flat of No. 26. A noted botanist, the local recorder for the, Botanical Society: with discoveries of rare plants to her credit, she had a small holding near Tickenhalt fare and sold flowers and vegetables in the Clifton area, traveling round in an ancient bull nosed Morris as late as the 1950s. She was assisted by “Millgrove", who came asking for casual employment during the thirties slump, was employed and housed by her for the rest of her lie, and looked after her when she was ill. Her flat was always in disorder, and her herbarium, by contrast, meticulously cared-for and orderly.

Arthur Woodruff and his wife lived in No. 32 for about thirty years, from 1932 until it was bought by Acker Bilk. Mrs. Woodruff was a great collector of subscriptions for the Garden Committee. Her brother, William Chivers, lived in No. 38 (1934-39) with two sisters and drove a "fluid flywheel"' Sunbeam Talbot so slowly round Bristol that he was known to the police as “Segrave" (holder of the world

44

speed record). Mr. Woodruff was a lay-clerk at the cathedral, with a fine counter-tenor voice, and supplemented his income by working as a cabinet-maker, originally for a firm of carpenters but latterly on his own. His basement workshop in No. 32 was always full of beautiful pieces that he was either restoring or making with old wood he had purchased, and these he would sell - if he felt like itto a private clientele. He was often visited by canons from the cathedral; he respected them for their education and breeding, but of some he was critical, feeling that they drew large stipends for very little work and that they had little knowledge of the lives of ordinary people.

In the thirties too Mr. Kohler from No. 13, wearing a high stiff collar, would sit under the silver birch reading Dickens, laughing to himself as he read and calling the attention of a passing child to the humour of the passage. While Mr. Webb sat in the front window of No. 8 doing the Times crossword, his daughter would bewail the disappearance of all the ripe raspberries in her front garden. And Margaret Holmes from No. 10, daughter of the long-serving Treasurer and later - much later - an archivist in Dorset, would climb the crab-apple tree in the middle of the grass and declaim from the Scriptures: "This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.”

The stern Wiss Jodrinkton used to tap on her window to reprove the noisy children circling outside No. 6 and ringing, their bicycle bells, and at the other end of the square Miss Ogilvie, known to some as "the Ogre” played her piano so loudly in No. 35 that it could be heard in the bungalow at No. 7a. Miss Ogilvie, full of wisdom and much-travelled, wearing her leopard-skin coat, was once asked by one of the Miss Chivers whether at her advanced age she felt ready to die: "On a spring day like this," she said, "I want to live for ever. In winter I don't mind.”