Fair housing no

UWM English professor revea shaped resistance to

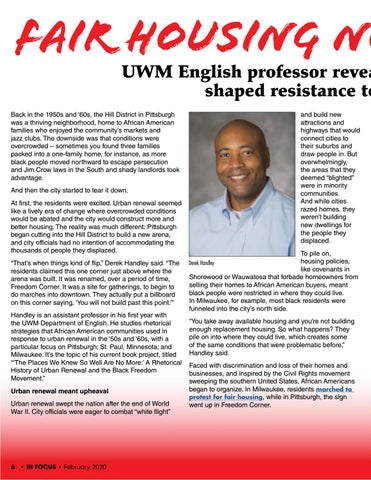

Back in the 1950s and ‘60s, the Hill District in Pittsburgh was a thriving neighborhood, home to African American families who enjoyed the community’s markets and jazz clubs. The downside was that conditions were overcrowded – sometimes you found three families packed into a one-family home, for instance, as more black people moved northward to escape persecution and Jim Crow laws in the South and shady landlords took advantage. And then the city started to tear it down. At first, the residents were excited. Urban renewal seemed like a lively era of change where overcrowded conditions would be abated and the city would construct more and better housing. The reality was much different: Pittsburgh began cutting into the Hill District to build a new arena, and city officials had no intention of accommodating the thousands of people they displaced. “That’s when things kind of flip,” Derek Handley said. “The residents claimed this one corner just above where the arena was built. It was renamed, over a period of time, Freedom Corner. It was a site for gatherings, to begin to do marches into downtown. They actually put a billboard on this corner saying, ‘You will not build past this point.’” Handley is an assistant professor in his first year with the UWM Department of English. He studies rhetorical strategies that African American communities used in response to urban renewal in the ‘50s and ‘60s, with a particular focus on Pittsburgh; St. Paul, Minnesota; and Milwaukee. It’s the topic of his current book project, titled “‘The Places We Knew So Well Are No More:’ A Rhetorical History of Urban Renewal and the Black Freedom Movement.” Urban renewal meant upheaval Urban renewal swept the nation after the end of World War II. City officials were eager to combat “white flight”

6 • IN FOCUS • February, 2020

and build new attractions and highways that would connect cities to their suburbs and draw people in. But overwhelmingly, the areas that they deemed “blighted” were in minority communities. And while cities razed homes, they weren’t building new dwellings for the people they displaced. To pile on, housing policies, Derek Handley like covenants in Shorewood or Wauwatosa that forbade homeowners from selling their homes to African American buyers, meant black people were restricted in where they could live. In Milwaukee, for example, most black residents were funneled into the city’s north side. “You take away available housing and you’re not building enough replacement housing. So what happens? They pile on into where they could live, which creates some of the same conditions that were problematic before,” Handley said. Faced with discrimination and loss of their homes and businesses, and inspired by the Civil Rights movement sweeping the southern United States, African Americans began to organize. In Milwaukee, residents marched to protest for fair housing, while in Pittsburgh, the sign went up in Freedom Corner.