7 minute read

Arts and Humanities

Why is the Medusa male? Globalization and glocalization in RomanoBritish sculpture

Chelsea Peer

Advertisement

‘Will coronavirus reverse globalization?’ (Bloom, 2020). A headline from the BBC asked this in April. It exemplifies how this formidable force causing large scale connectedness in economies across the globe has weighed on our minds for the past several decades and even now amid an unprecedented pandemic. Yet, while globalization has largely been an economic and political term, its effects on culture and human interconnectedness have caused it to seep into the thought of the humanities as well, including my area: the archaeology of Roman Britain.

‘Globalization’ vs ‘Romanization’

Since the early 1900s, the term ‘Romanization’ has dominated the study of Roman Britain (Haverfield, 1905, 1912). In short, Romanization theorises that as Rome exerted influence over its territories, provincial elites strove to emulate their Roman rulers and their acceptance of Roman culture ‘trickled down’ over time into the lower classes. Today, the concept of Romanization is treated with distaste, but scholars have struggled to replace the framework. Versluys has criticised the approach of many Roman Britain scholars for allowing themselves to fall back into the framework of Romanization, rebranding it as globalization without fully moving on from the theory (Versluys, 2015: 146). There has been plenty of condemnation of Romanization, but in a way that is especially unfruitful (Versluys, 2014: 4).

In his own work, Versluys proposed a way of looking at the visual material culture of the Roman Mediterranean through the lens of globalization. He argues that a mistake made by previous approaches focussing on acculturation was creating ‘cultural containers like “Egypt”, “Greece” and “Rome”’ (Versluys, 2015: 149). As Versluys puts it: ‘What we need, therefore, is a concept that has x

Figure 1 ‘Statue of Isis-Fortuna at The British Museum © The Trustees of the British Museum’.

and y as relative categories that are part of the same cultural container. We need, in other words, a concept in which not linear relations are central, but continuous circularity is’ (Versluys, 2015: 146). As an example, he carries out a short exploration of the goddess Isis and her spread through the Hellenistic and Roman worlds (Figure 1). He writes: ‘she was a Hellenistic, Mediterranean innovation of the old Egyptian Isis and, moreover, that Egyptian priests themselves played a crucial role in establishing this innovative “translation”’ (Versluys, 2015: 149). She was integral ceremonies opening the Roman seafaring season ‘where “Egyptian” and “Roman” apparently have become synonyms’ (Versluys, 2015: 149). We can thus not talk about an interpretatio graeca or romana of something “Egyptian”’ as all three cultures were involved in the creation of Isis as she existed in the time of Rome (Versluys, 2015: 149).

Van Alten takes this angle on globalization and adds to it the concept of glocalization—a process ‘involving the interpretation of the universalization of particularism and the particularization of universalism, the so-called paradox of globalization or the local-global nexus’ (van Alten, 2017: 2). He reiterates Versluys’ conclusion on Isis and argues that glocalization ‘offers perspective, since it is able to study the described religious material not just as solely bottom-up or top-down processes.’ The material culture of the Roman provinces shares characteristics seen throughout the empire ‘which makes it trans-locally recognizable,’ yet ‘locally different’ (van Alten, 2017: 7). Van Alten calls on the arguments of Van Andringa (2002, 2007), whom he writes ‘argues against visions of Roman and native religion as coexisting… because this implies that both religious cultures were static non-changing entities before Roman conquest’ (van Alten, 2017: 7). Rather, religious communication allowed for local communities ‘to express their understanding of their place in a global context and in relation with other local communities’ (van Alten, 2017: 7) which lead to the creation of new communities, establishing ‘new religious expressions in which both local and global interests were combined’ (van Alten, 2017: 7). Both Versluys’ and van Alten’s approaches assert treating postRoman conquest cultural development as catalysts for new creations, and this may

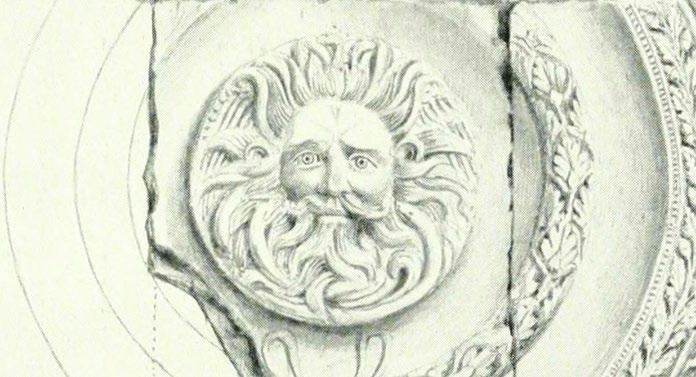

Figure 2 Reconstructive drawing of the Gorgon head at the Temple to Sulis Minerva at Bath. (From Jackson, 1913: pl. 133)

Figure 3 A nest of severed head sculptures from Entremont in southern France. (From Wikimedia; Creator: Michel Wal. Under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License. Changes made.)

get at the heart of why we have thus far struggled to describe what was happening in Roman Britain without Romanization.

The Application of ‘Globalization’ and ‘Glocalization’ to Romano-British Sculpture

I will be taking this framework Versluys and van Alten used to explore cultural exchange in the Mediterranean and Germany and assess their application on Romano-British sculpture with Classical subjects. Romano-British stone sculptures have often been treated as poor attempts to emulate the Mediterranean style (Collingwood and Myres, 1936: 249-50; Johns, 2003). However, I argue that rather than trying and failing to copy their Roman rulers, the artists of Roman Britain were taking the Classical ideas brought into their society and interpreting them in their own ‘glocalized’ way. I have already begun to test this in the case of the Romano-British Gorgon and plan to expand to other Classical figures in my dissertation.

The Medusa was portrayed in the Roman Mediterranean as a beautiful woman with locks of snakes for hair. In the Mediterranean, she was treated primarily as an amulet of protection, and often appeared in funerary context (Toynbee, 1971). Moving into Britain her purpose remained much the same, however, there is one glaring difference in the case of stone sculpture: the Romano-British Gorgon is often depicted as male. a more instructive example is one on a tombstone pediment found at Chester. Celtic style artwork features large expressive eyes in contrast with the Mediterranean preference for realism, and this example of a male Gorgon exhibits a style of eye which provokes the Celtic tradition of the ‘severed head’. While still unrealistically large and round, the eyes are undetailed and ‘puffed’ (Armit, 2012: 178, Illustration 6.5) in appearance. They appear as though they may be closed (Armit, 2012: 178), and closely resemble the eyes of severed heads found at Entremont (Fig. 3), an ancient cultural landmark in southern France which features the severed heads of vanquished enemies whose closed eyes ‘reflect death, closure, absence of engagement and the negation of being’ (Aldhouse-Green, 2004: 191). Could this be the traditional depiction of the severed head of warriors creeping its way into depictions of the Classical Medusa and incorporating older conventions for illustrating death?

Conclusion

As the Gorgon maintained many of her long-established traits, most especially her protective powers, she was changed by Britain’s own local cultural context. In Roman Britain, the ‘global’ concept of Medusa was adopted and adjusted by local contexts in a way that more closely fits the definition of ‘glocalization’ than ‘Romanization.’ I believe exploring this approach in my dissertation can improve our understanding of Romano-British art, religion and the people’s relationship with the rest of the Roman world.

Aldhouse-Green, M., 2004. An Archaeology of Images: Iconography and cosmology in Iron Age and Roman Europe. Routledge, London. Armit, I., 2012. Headhunting and the Body in Iron Age Europe. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi-org.ezphost.dur. ac.uk/10.1017/CBO9781139016971 [Accessed 26/3/20] Bloom, J., 2020. Will coronavirus reverse globalisation? BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/ business-52104978 [Accessed 2/4/20] Collingwood, R.G., Myres, J.N.L., 1936. Roman Britain and the Anglo-Saxon Settlements. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Haverfield, F.J., 1905. The Romanization of Roman Britian. The British Academy II. https:// babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/t?id=mdp.390150684 78752&view=2up&seq=1&size=150 [Accessed 11/4/20] Haverfield, F.J., 1912. The Romanization of Roman Britain, 2nd ed. Oxford at the Clarendon Press, London. http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/ epub/14173/pg14173-images.html [Accessed 11/4/20] Jackson, T.G., 1913. Byzantine and Romanesque Architecture. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://archive.org/stream/ byzantineromanes02jackuoft/byzantineromanes 02jackuoft#page/n290/mode/1up [Accessed 30/4/20] Johns, C., 2003. Art, Romanisation, and Competence, in: Roman Imperialism and Provincial Art. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 9–23. Toynbee, J.M., 1962. Art in Roman Britain. Phaidon Press Ltd, London. Toynbee, J.M.C., 1971. Death and Burial in the Roman World. Cornell University Press, USA. van Alten, D., 2017. Glocalization and Religious Communication in the Roman Empire: Two Case Studies to Reconsider the Local and the Global in Religious Material Culture. Religions 8, 140–160. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8080140 [Accessed 2/4/20] Versluys, M.J., 2014. Understanding objects in motion. An archaeological dialogue on Romanization. Archaeological Dialogue 21, 1–20. https://doi-org.ezphost.dur.ac.uk/ [Accessed 13/4/20] Versluys, M.J., 2015. Roman visual material culture as globalising koine, in: Globalisation and the Roman World: World History, Connectivity and Material Culture. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 141–174. https:// www-cambridge-org.ezphost.dur.ac.uk/core/ services/aop-cambridgecore/content/view/ D688BC6C8B854F4A4BE67C883 626574D/9781107338920c7_p141174_CBO. pdf/roman_visual_material_culture_as_ globalisingkoine.pdf [Accessed 15/2/20] Wal, Michel. Têtes coupées Entremont. [Online] Available from: https://commons.wikimedia. org/wiki/File:T%C3%AAtes_coup%C3%A9es_ Entremont.jpg [Accessed 29/4/20]