5 minute read

Green technologies in cooperative date farming in the Jordan Valley Katie Stobbs

Green technologies in cooperative date farming in the Jordan Valley

Katie Stobbs

Advertisement

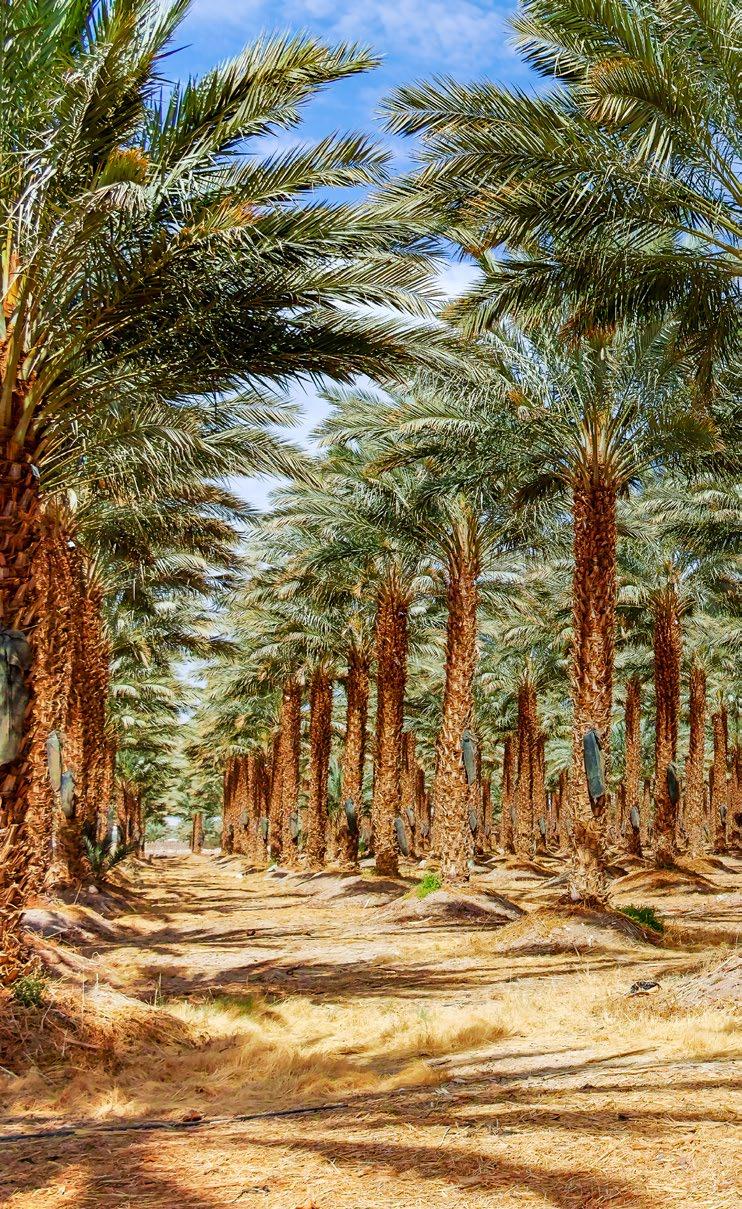

Underserviced communities in the West Bank often lack access to water for agriculture and consistent energy supply for groundwater pumping. This is especially true in the Jordan Valley of the West Bank where date farming is the dominant crop. Agriculture is an essential economic and cultural activity for Palestinian farmers and the Jordan Valley is considered Palestine’s “food basket” due to its distinctive location and optimal climate conditions. The cultivation of date palms is concentrated within this region and in the greater Jericho area (Daiq 2006).

Water resources are a vital element of Palestinian ecosystems and lack of access to these resources remains a key point in the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians in the region (Shevah 2014). Sources consist mainly of surface and groundwater resources (springs and wells). Limited water resources have led to over-extraction from the shallow aquifer which leads to deterioration of water quality, increasing the water salinity. Date palms only require twenty percent of the water required by banana trees, and are more tolerant of salinity than other crops such as vegetables and cash crops. Thus, due to the deterioration of the water quality and increased salinity of water in the Jordan Valley, date farming in the Jordan Valley and Jericho regions can be considered an acceptable solution to the lack of availability and quality of water sources.

However, the growth of date palm cultivation in the Jericho and Jordan Valley regions has not reached its full potential; there are numerous barriers impeding progress. Insufficient water is the greatest factor hindering the expansion of date palm cultivation. Despite the fact that date palms can survive in arid conditions due to their increased tolerance to salinity, there needs to be sufficient irrigation of adequate quality in order to maximise potential yields (Abu-Qaoud 2015). Additional obstacles include steep investment costs, poor marketing, and unfair competition from Israeli products (Ighbareyeh et al. 2015). This is partially due to the continued control of land, water, market

Image caption: Solar PV farm, date processing, and farmers and technicians consulting about date palm crops in the Jordan Valley.

and borders by Israel, which generates high production, transportation and marketing costs. The inadequacy of official support policies from the Palestinian Authority for date palm cultivation and for the agriculture sector generally, also hinders development and results in a weak marketing system (Daiq 2006).

The future of irrigation in the Middle East is treated wastewater. Israel has already begun to move irrigation from freshwater sources and into treated wastewater use. The Israel Water and Sewerage Authority has stated that freshwater is to be capped for agriculture and any additional water provided to farmers will come from treated wastewater. Treated wastewater is even more significant for irrigation in the West Bank where fresh water supplies are severely limited. Many communities also lack a public sewage network, so untreated wastewater from unlined cesspits either percolates into the groundwater sources or is collected by sewage tankers and disposed in open areas, which is harmful to residents’ health and the environment. Recycled wastewater is therefore an asset to farming and should be valued as such.

Equitable and reliable access to water is essential for social and economic development and for building peace and stability among peoples and nations. Manoeuvring through the political bureaucracy to obtain permits to update existing or construct new systems, such as the drilling of new wells, is both challenging and time-consuming and often takes years to implement, if at all. On the other hand, low tech, local on-site wastewater treatment offers a comprehensive solution to water needs for marginalised, off-grid communities (Mcilwaine and Redwood 2010). This decentralised approach, provides water and food security for these communities and the local treatment of waste reduces the impact of pollution on shared natural resources, thereby mitigating conflict.

Water and energy are borderless resources; Israelis and Palestinians are in desperate need to find better ways to equitably share the costs and benefits of environmental management. Successful conflict mitigation over cross-border water and energy needs in Israel and Palestine lies in the success of people to people (P2P) activities. Regional environmental projects have been shown to reduce conflict by building trust; relationships yield partnerships and partnerships yield trust. Such relationships can be replicated, enhanced and strengthened when local communities engage with one another on local solutions for water treatment, renewable energy and food security projects.

P2P partnerships have brought together conflicting neighbours to learn about, design, implement, and monitor technologies that offer mutual benefits for improved water, wastewater, and energy services. From 2014 – 2016 I witnessed firsthand the positive impact such collaborative partnerships can have whilst working on the joint Palestinian Wastewater Engineers’ Group/Arava Institute for Environmental Studies’ project to install on-site greywater treatment systems, drip irrigation systems and solar PV powered desalination plants in off-grid communities in the Jordan Valley. Beneficiaries were trained by joint Israeli and Palestinian teams and a joint Israeli-Palestinian water committee for the Al-Auja spring was established, thereby fostering cooperation and mitigating conflict and as a result, enhancing and promoting social and trade relations between Israel and Palestine.

There are a range of benefits to this P2P approach, including the obvious economic, environmental and health benefits alongside perception change of “the other” and acknowledgement of mutual interest to cooperate over local solutions to transboundary resource management. This in turn promotes improved local and regional governance, and can be influential in long-term policy solutions.

Through such cooperative efforts, joint Israeli and Palestinian initiatives in date farming have provided an opening for agreements on transboundary resource and agricultural management, and hopefully in the future, a comprehensive trade agreement for dates between Israeli and Palestinian growers. By investing in problems that affect people’s everyday lives and livelihoods, mutual cooperation can provide practical dividends in addition to environmental and social benefits.

References

Abu-Qaoud, H. (2015). Date Palm Status and Perspective in Palestine. Date Palm Genetic Resources and Utilization (pp. 423-439): Springer. Daiq, I. (2006). Date Palm Economies and Cultivation Circumstances in Palestine. Paper presented at the III International Date Palm Conference 736.

Ighbareyeh, J. M., Cano-Ortiz, A., Carmona, E. C., Ighbareyeh, M. M., & Suliemieh, A. A. (2015). Study of Biology and Bioclimatology of Date Palm (Phoenix Dactylifera L.) To Optimize Yield and Increase Economic in Jericho and Gaza Cities of Palestine. International Journal of Research Studies in Biosciences, 3(1), 90-97. Mcilwaine, S., & Redwood, M. (2010). Greywater Use in the Middle East: Technical, Social, Economic and Policy Issues. (S. Mcilwaine & M. Redwood, Eds.). International Development Research Centre. Shevah, Y. (2014). Adaptation to Water Scarcity and Regional Cooperation in the Middle East. In S. Ahuja (Ed.), Comprehensive Water Quality and Purification (Vol. 1, pp. 40–70). Elsevier Ltd.