13 minute read

The UnspOken feAr

Undocumented immigrants discuss their experiences living in uncertainty

ARTICLE & PHOTOS BY ANIBAL GONZALEZ • DESIGN BY ABHISHEK MYNAM

Advertisement

Editor's Note: Given the sensitive nature of the topic, Santiago's name has been changed to protect the student's identity.

ere in our beloved Bay Area, known for its diversity and

Hprogressive culture, immigration is a powerhouse which contributes to its beauty. But as much as we as a community accept each other and refrain from discriminating based on legal status, it does not take away from the fact that legal persecution is still practiced. This reality is something many individuals all over the Bay deal with and our close community at UPA is no exception. In this piece, I wish to discuss not just the statistical aspects of immigration but rather dig into the reality immigrants share from an emotional standpoint: mental strain that is applied on a daily basis.

Fear is an emotion that I found is greatly shared in the community, beginning with association. Undocumented immigrants are very skeptical of seeking aid regarding their immigration status as they fear the association of not having documentation. Many avoid the topic entirely and try to stay under the radar at all times.

This became vividly evident to me as I attempted to set up interviews with individuals to discuss their experiences. Unfortunately, I was met, time after time, with the same response: “my relatives do not feel comfortable talking about this.” It opened my eyes to the fear of associ-

Maria Murillo’s boyfriend jumped over the border fence to be with her. ation—that mentioning anything related to their immigration could link them to the U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) or other authorities that would get them deported or in legal trouble. Fortunately, I was able to find a few individuals that were kind enough to sit with me and share their experiences coming from the standpoints of a teacher, student and family relative.

All my sources immigrated at a young age and have been living here most of their lives. The U.S. has become their second home— something I, myself, can relate to as an immigrant from Nicaragua. The teacher who was able to sit and discuss with me was Spanish teacher Maria Murillo who explained the lack of choice she had in her immigration from Mexico.

“I was undocumented because, in 1988, I was still a little bit of a minor and only had six months left to become of age, and at that time, my father did not ask me if I wanted to come to the United States or not,” Murillo said. “Simply, ‘I am the father and you do what the father says.’ So, father told us we had to go. So, here I was—we could say that I was undocumented without choice.”

Murillo has mourned the life she could have lived in her homeland.

“Even these days, I feel that I was ripped off of my homeland, which was rightfully mine,” Murillo said. “Of course, now seeing the beauty of my country through videos and images, well, it makes me sad.”

As those words came out, I could feel the somberness in her voice.

Murillo lived 33 years of her life in a place where she did not want to be. Being brought to the United States by their parents in hopes of a better future is a harsh reality that is known throughout the immigrant community, like Murillo, who has lived 33 years of her life in a place where she did not want to be. Nevertheless, the feelings of homesickness were never mended. Murillo had to move on since back home, there were not many financial opportunities left for her.

Upon immigrating, Murillo also became wary due to the prevalence of misinformation regarding how to obtain citizenship. Traditionally, there are three ways of obtaining citizenship: individual petition, alien relative petition and asylum.

“When there are people that are undocumented just getting here, in most cases, there is no information on how to get started in any kind of legal process,” Murillo said. “This is one of the first fears in which one as an undocumented immigrant goes up against. The first fear is that there is no information or much misinformation. So, when they misinform you there is no other option but to wait.”

So, that was what she did—Murillo ended up waiting for more than 20 years to secure her citizenship in the United States. She first attempted to have peace of mind through her brother who came here before she did; he was more legally stable and was able to inquire about citizenship for her. “Asking for a relative,” or Petition for Alien Relative, is a term used in the legal system to represent the action of wanting to change the legal status of a relative

between close relatives. It is often easier and quicker for sons and daughters to ask for their parents and siblings, rather than them ap“ plying as individual cases. On the other hand, it is a longer process as the government ranks cases by priority with siblings being one of the most lengthy.

Unfortunately, this did not end up working out for Murillo. She explained that in 1995, she claimed political asylum, but ultimately, it did not work out. This process put her in a sort of “legal stasis,” allowing her to try and find another way to secure her stay. Ultimately, the factor that allowed for this to work later on was her son, as him being a “ U.S. national compelled the U.S. embassy to grant her residency in 2000.

“The only thing I remember is the judge told me that the case was dismissed because of what I had presented and the necessities of my son because he would have suffered as a U.S. citizen in Mexico, so they would give me the residency so that my son wouldn't go through that,” she recalled.

However, it took another 15 years of hard legal appeal to get her naturalization. Those years were rather difficult for her as she suffered from depression ever since she can remember. Changes in her life certainly aided her in this mental battle, such as her boyfriend at the time, starting a family and having a son. There were setbacks, of course; her brother passed away early in her stay in the U.S. She still does not feel fully content living here.

“I would say that 80% yes [immigrating was worth it] and 20% I would say no, because life in the U.S.A is too much in a hurry.” However, this feeling is not comparable to her being completely discontent living here when first arrived.

A student at UPA experienced a similar process of immigrating to the U.S. Santiago, who is going by a pseudonym to preserve his anonymity, is someone I have known for quite a while. They are a very caring and driven individual who is always shooting to do their best. They were brought here to live with their mother in 2009 to seek a more successful life.

“I pretty much do enjoy living here—there is much potential in the U.S.,” Santiago said. “But sometimes I do miss my family back home. It’s been years since I have seen them.”

Opportunities in the U.S. are very difficult to take advantage of, but that does not stop immigrants from trying. In Mexico, struggles such as poverty and violence are common.

“The struggles here are way better than they were in Mexico,” Santiago said.

Regardless of that, unfortunately, because of their immigration status, they can not go back. Something that all immigrants go through is the pain of missing their relatives and not being able to go see them or losing them and not saying their last goodbyes. If they did, the cost of that would be all of their hard work lost. They are not able to go back, and if they do, they will most likely restart from square one.

What they can control is not going back. “Nowadays, I kinda just accept it. I have gone through so many things, you kinda just accept it… If it’s meant to happen, it's meant to happen. It’s still a factor in the back of my mind,” Santiago said. This constant mental burden weighs on his self-esteem. “I used to think of myself as inferior because I was undocumented,” Santiago said. Today, Santiago embraces his status and proudly said, “I am part of that community.” Spanish teacher Nico Mendoza's dear friend for many years, Fernando Vega, was kind enough to speak with me on the phone. As a busy, hard working man, that was the only way he could make time for me; the hour and a half long talk was nonetheless very helpful. He explained the initial changes he faced upon immigrating to the U.S. “The first few years are the hardest, especially the first one when you come to a change,” Fernando said. “A new country, a new culture. The friends, family, the girlfriend—you leave it all behind to come here to something new. The first year is the hardest.”

Vega initially came to the US in 1984 with the intention of preparing a home for his mother.

“I am going to the U.S. for one year, so I can build my mother a brick house, so that we would live a little better as there were so many shortcomings. That was my plan, that was my goal. But as time went on, I kept adapting, and without realizing, I stayed for all this time,” he said.

He started to enjoy living in the U.S. more and more, adapting to the new culture, new people, and the new lifestyle. He stayed here indefinitely which led him to a period of undocumentation lasting more than 30 years.

However, responsibilities started to pile up on him. After having met his now wife and starting a family, he was faced with having to look out for his new family. Vega took it upon himself to try more seriously to obtain legal

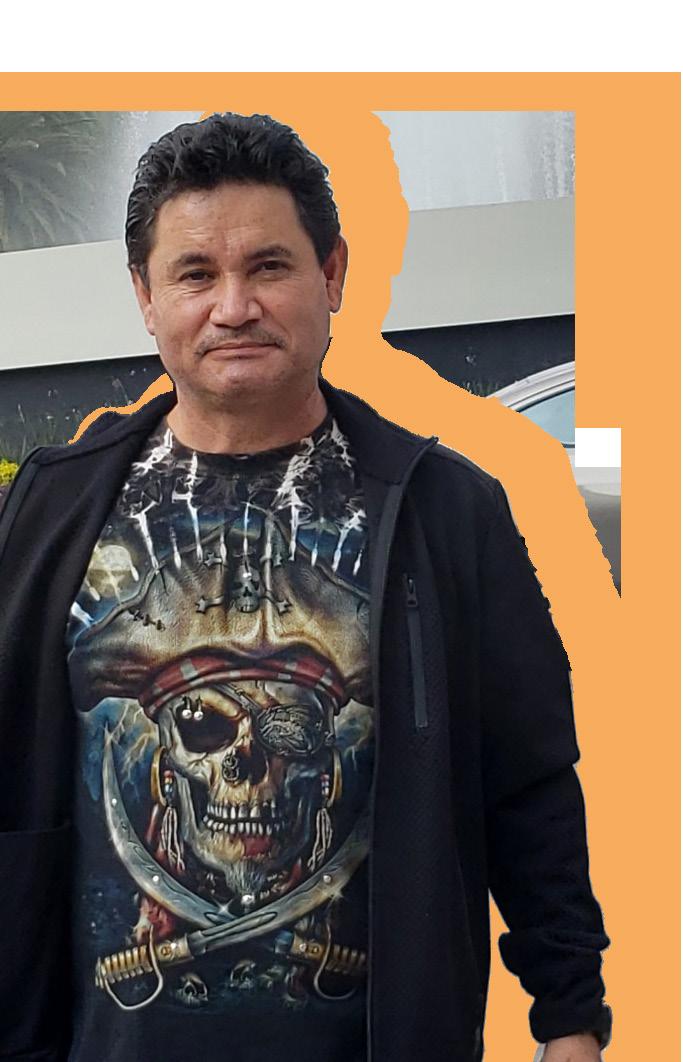

But sometimes I do miss my family back home- it's been years since I have seen them. - santiago Santiago immigrated to the U.S. when he was five.

I thought I would just sneak back in. The turning point was when I got married in 1991. When I got married I now had a family which led me to buy a house in 1994 and apply for a loan which I thought would not get approved, which ended up being approved. I understood now that I had goods and also that I now had two kids. Fear started to creep in, fear of not being able to pay my mortgage if deported. Would I be able to support my family?” Unfortunately, his efforts to obtain U.S. citizenship were unsuccessful. Vega tried to pretend to be a field crop picker to obtain a work visa but was ultimately discovered to “ not have been a worker. He then attempted to obtain legal status through legislation which fell through due to him not meeting a requirement of arrival time in the U.S. He then opted for naturalization through the request of an Alien relative. His son started the process and gained his nationality.

All of the individuals I spoke to came from different backgrounds and came here for different reasons but with each interview, I kept seeing similarities of their experiences throughout the years. One question I asked all of them was, “Are you and were you fearful of deportation?” All their answers were alike: they all stated that towards the beginning, fear was ever present.

“If it’s meant to happen, it is meant to happen,” Chino said.

But each had a goal that needed to be accomplished. As time went on, the fear never went away, but rather, it became more repressed in their minds. For the adults, there was a turning point for them where the fear became absolutely constant for them—when their family was involved. “The reason I had a fear of deportation was because I already had kids,” Vega said. Once a child was involved in the situation, they lost all care for themselves and put their minds to their children. What they feared the most was that if they were to get deported, they would no longer be able to take care of their children. All of them stated that they, in fact, did not have a plan if they were to get deported but rather rode on the assumption that they would go to their family members back home. The major issue as to why they had no ability to save money or prepare was due to time constraints. “You need six circles to get a rectangle,” Murillo said. She explains that here in the U.S., life is extremely fast-paced compared to Latin American countries, so to survive here, you need four wheels (four circles), a steering wheel (one circle), and a watch (one circle) to

Fear started to get money (the rectangle). It is difficult to strike a balance creep in, fear of with all of those, and adding not being able to the difficulty of being undocumented, always looking over pay my mortgage if your shoulder and trying to fit in, it can be very stressful and deported. Would I be draining to live this way. The more I listened, the able to support my more I could sympathize with what they went through or are “ going through. Being an immigrant myself, I have had the privilege of having documentation all my stay here in the U.S., which I am truly grateful for. But discrimination and fear are experiences that I have shared with them—my parents tellfamily? - Fernando vega ing me even though I was a resident, that did not mean I was safe, advising me to always be aware of the police and be on my best behavior. Never raise too much attention to yourself, as you are never truly safe legally until you are declared a national U.S. citizen. The process and feelings they expressed to me about adapting to the new environment resonated so deeply that I found myself nodding my head to every word that they said. Murillo’s interview especially stayed in my mind long after it took place when she told me that she does not enjoy living here completely. She went on to compare the lifestyles she saw when she visited Mexico, describing it as a more difficult lifestyle, but the people are happy, seeing them relaxing on their front door chatting, drinking, playing, socializing and just enjoying life. I have never been to Mexico, but when she was telling me about it, all I could picture was me at my home town in Nicaragua, walking down the street looking for my friends to play something while the neighbors asked how my dad was doing as they chatted about the hot gossip in town. Late at night, the adults would go inside, and we would just sit in front of someone’s house and tell jokes, play games and just chat until we got yelled at to come back inside. It made me feel a sort of melancholy comfort, relating to her experiences and remembering things I have not done in half a decade. Truthfully, I cannot fully say I relate to them completely because I have been very privileged for my stay in the U.S. as a documented immigrant. But their stories truly showed me the hardships of someone not as privileged as me and how strong they have to be to keep fighting this battle. These individuals go through so much in their lives but never lose their hope of working for a better one. Vega now considers the U.S. his home. 37 | in-dePth