6 minute read

Bridging the Divide

Pioneering, research-based outreach programs that target and empower the underserved

Advertisement

For more than 65 years, students and faculty at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine have been

committed to easing the burden that poverty, drugs, disease, and discrimination place on

the area’s medically underserved. The school has implemented innovative, research-based

outreach programs designed to improve the health and lives of Miami’s vulnerable community.

And it’s worked. But this past year, COVID-19 interrupted and threatened to kill that progress.

Two Miller School physicians refused to let the virus win.

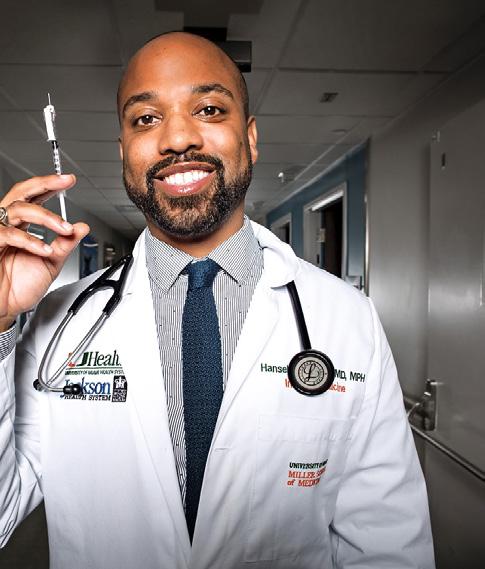

Hansel Tookes, M.D., M.P.H., associate professor of clinical medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, has spent his career fighting for social justice and equality in marginalized communities. He’s been a staunch proponent of implementing syringe service programs (SSPs) to reduce the rate of HIV, hepatitis C, and other blood-borne diseases. In 2016, he founded the Infectious Disease Elimination Act (IDEA Exchange) an SSP that offers resources for people who inject drugs.

Through this program, Tookes and his staff not only continued their routine efforts during the COVID-19 outbreak but provided free vaccinations that boosted community outreach and proved the viability of using telehealth to treat addiction.

Tookes and his staff promoted the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination, obtaining media coverage on the first day of vaccination at Jackson Memorial Hospital—the first and, for a time, only vaccination site for the surrounding community in Miami—and mounting an aggressive media and educational outreach campaign. He realized then that a large demographic was missing from the queue, alerting him to the potential for dangerous inequities in vaccine distribution.

“The cars were very fancy,” Tookes says. “I was very vocal that we needed to make sure that the people we were vaccinating reflected the people we serve in the hospital, and it wasn’t necessarily that way. Our patients in the hospital are black and Hispanic and poor, so we needed to make

sure that we were redoubling efforts to vaccinate this community.”

He partnered with Jackson to start an aggressive vaccination awareness campaign that featured town halls with Jackson staff, influencers, preachers, and business owners. Other outlets included live televised events, PSAs, and social media blitzes. Tookes says that Jackson picked up the slack of vaccinating members of the black community, which accounted for roughly 50 percent of the African-American population in all of Miami-Dade County.

“I really started advocating for vaccine equity in the press,” says Tookes. “This was really my community engagement over the past year.”

Tookes guessed correctly that substance use would increase during the pandemic, so he kept IDEA open. Students running the free clinic there suggested using telehealth to continue prescribing medication amid social distancing protocols. “Our patients usually don’t have access to WiFi and all of the technology, so we brought the technology to them,” Tookes says. “We worked with Jackson to develop an electronic prescribing system (for addiction medications) and then received funding from the state to pay for 100 people to be in treatment. So we were able to prove the concept during the pandemic. And now we get to do a clinical trial to show that telehealth might be considered best practice. We created something out of nothing.”

Tookes’ work this past year earned him the Avenir Award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, a $2.3 million, fouryear award that will support his research project, “Tele-Harm Reduction for Rapid Initiation of Antiretrovirals in People Who Inject Drugs: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” The Tele-Harm Reduction program enlists three physicians who are on call with rotating schedules to respond to patients, regardless of their location.

The program leverages telehealth technology, as well as the trust that IDEA has built in the community. The current SSP framework also shows great promise as an adaptable and transformative model for bringing HIV care out of a traditional healthcare clinic, sustaining viral suppression among people living with HIV who inject drugs, increasing the use of medications for opioid disorders, and curing patients with hepatitis C. It’s hard to believe a pandemic could result in so much positivity.

“It was so amazing that we had the technology. I felt so connected to them at a time when life was so uncertain,” Tookes says. “I’m very thankful I had the army of courageous staff on my team.” For more than 10 years, Armen

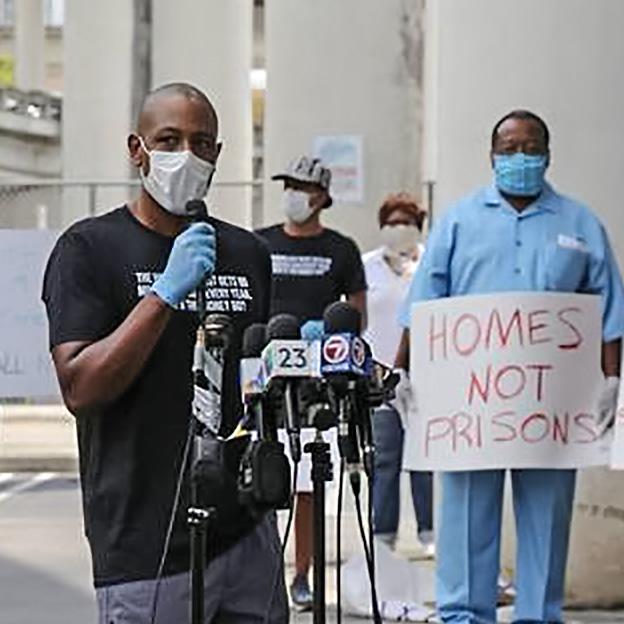

Henderson, M.D., hospitalist at UHealth

Tower and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Miami Miller

School of Medicine, has brought medical care to Miami’s inner cities. Like Tookes,

“Our patients usually don’t have access to WiFi and all of the technology, so we brought the technology to them.” — Hansel Tookes, M.D., M.P.H.

he cares for a community ravaged by diabetes, HIV, high blood pressure, asthma, sickle cell anemia, obesity, poverty, and systemic racism. He’s a leader in building projects that see the job through. In 2014, he became a co-organizer for Dream Defenders, a social advocacy group that focuses on helping vulnerable populations obtain access to the social determinants of health. He also founded Dade County Street Response (DCSR), which trains and educates medical professionals for disaster resilience efforts. When hurricanes or tornados loom, Henderson and his team move to provide free medical care, disaster relief education, food, water, and shelter for people most affected by poverty and oppression.

COVID-19’s consequences mirrored that of a natural disaster, and because DCSR was already equipped for triage, Henderson’s team handled the outbreak in a similar fashion. They spent countless hours helping the area’s homeless and poor obtain free COVID-19 testing, face masks, information about the virus, and full hygiene services. The urgency here was to outpace the disease, which would spread quickly across a population marked by underlying health conditions.

“By the middle of the pandemic, we were providing toiletries, offering showers. We had bathrooms, we had handwash stations, we were testing individuals. We probably tested over 500 individuals and served thousands of people over a span of seven months,” says Henderson, who joined hundreds of volunteers at St. John’s Baptist Church in Overtown. “Being able to advocate on behalf of this community is important, but so is knowing that it follows a long tradition of helping with people who are struggling to survive.”

— Armen Henderson , M.D.

One of the most rewarding aspects of his work is knowing that the community he serves can rely on him no matter what. For Henderson, there is no determinant of care other than being a person in need. This makes it all the more galling that a police officer handcuffed and detained him last year while loading a van outside his home with tents for the homeless. The police officer inexplicably thought he was dumping garbage and released him only when Henderson’s wife presented identification. The incident highlighted the social disease that threatens people of color as well as any deadly virus can.

“Being able to advocate on behalf of this community is important, but so is knowing that it follows a long tradition of solidarity with people who are struggling to survive,” he says.