11 minute read

Education Mindset

Educators share their stories of teaching through a pandemic on Education Mindset

By Tom Gerhardt, NDU Communications

Education in North Dakota shifted dramatically March 15, when Governor Doug Burgum, by executive order, announced that K-12 schools would close for a week to help slow the spread of coronavirus. That led to another announcement a week later that schools would close indefinitely. Soon after, the governor ordered schools closed for the year. Our colleges and universities followed suit.

School districts quickly developed plans for distance learning that led to the lightning-fast transformation of education in North Dakota. Educators, students, and parents were all thrust into an unexpected teaching and learning environment.

In an effort to capture a historical snapshot of the unprecedented change, North Dakota United began a new podcast called Education Mindset. Host Tom Gerhardt decided to zoom in on the McKenzie County Public School District in Watford City to help provide perspective. It’s not the largest district in the state, nor the smallest. It’s in the heart of oil country which brings in students and families from around the world. Oil prices plummeted at the time, imposing more stress and uncertainty upon Watford City as it dealt with the impacts of layoffs and economic uncertainty — disrupting the school system and the community.

How did educators educate? In a half-dozen episodes, you can listen to high school science teacher Amy Polivka — who is also the president of the Watford City Education Association. Tom also visited with a school counselor, a middle and high school band director, the coordinator of the English Learner program along with a staff member, a kindergarten teacher, and a library media specialist.

All are members of North Dakota United.

Veteran high school science teacher Amy Polivka left Watford City High School on a Friday in mid-March to go home for the weekend. It turned Amy Polivka out to be her last day in the classroom with students for the school year. By Sunday night, Governor Doug Burgum ordered schools to close immediately. The shift to counteract the impacts of COVID-19 happened so quickly and unexpectedly that educators across the state didn’t have a chance to say goodbye to their students in person.

Amy Polivka

It was the same story for thousands of educators and tens of thousands of students across North Dakota this spring. “And I think that was definitely an eye opener to us, a wake-up call, couple of days without school,” Amy Polivka said. “And then we all started thinking, what’s next? What do we need to do and how are we gonna finish up the school year?”

Answers to those questions began to take shape. Governor Burgum directed school districts to submit plans to the state by March 27th on how they were going to move forward with distance learning. It was new ground for administrators, educators, students, and parents.

Problems compounded in Watford City as plummeting oil prices reverberated around the region. “And we met and kind of discussed what we felt would be best Check out our for our community,” newsfeed at ndunited.org Polivka said. “Again, a community that’s been impacted by oil and a lot of people from diverse areas of the country. And the thought of how are they going to navigate this, schooling their kids at home and continuing to work, because at that time, we really did not foresee a lot of the oil field companies slowing down at that time. So that was kind of our biggest concern.”

The English Learner staff in the McKenzie County Public School District was up for the challenge. Pamela Albright works with students in grades 7-12. On top of helping families with technology, working through language barriers over the internet and other challenges, Pamela wanted to make sure she stayed connected to her kids. She had one student who had begun to drift away.

“I had her number and she wasn’t responding to other teachers. I was able to send her a text. Hey, are you OK? I even sent her a picture of some hot sauce she had told me about,” Albright said. “I asked did I buy the right one just to make her laugh and do some silly things. And she just reached back out yesterday after I sent her another text. Are you OK? I’m getting on it, Miss Albright, I’m getting work done.”

It’s just one example of teachers going out of their way, often outside of the normal school day, to stay connected.

Kindergarten teacher Delanie Hill faced another set of challenges. In many cases her students were still learning to read. “The Delanie Hill hardest thing with doing distance learning for kindergarten is that we are not teaching our students directly. We’re really teaching parents,” Delanie Hill said. “So, all of our lessons we’ve had to create. They have instructions in multiple formats. I mean, we’re having the instructions on the assignment.” Hill said time was spent translating instructions into Spanish, and that she and others created video instructions trying to find as many ways as possible to make distance learning easier on the parents and students.

Delanie Hill

Through the challenges, which included teaching from home while taking care of her own young children, Hill found successes to build upon. That included a child in her class who is a selective mute. “She participates and does the work, but I’ve maybe heard two full sentences out of her all year,” Hill said. “When playing with her friends, she doesn’t talk.

Once when playing house, she meowed because she was playing the kitten and the kids got all excited. I mean, that’s how much she was not talking at all. Well, now with distance learning, she’s doing it all. She’s submitting the recordings of herself reading to me. She’s doing this assignment and I get to hear her voice. And it’s a really cool.”

The challenges were equally difficult for high school counselor Rachel Meuchel. She says the biggest challenge was not being able

Rachel Meuchel to see their faces and have conversations face-to-face.

Rachel Meuchel

“Especially our students who don’t have the resources — that’s been probably one of the biggest challenges is being able to if they don’t have Internet or they’re sharing computers with their siblings or maybe they have one computer for the whole family, things like that,” Meuchel said. “It becomes a challenge to reach the kids that we would usually be able

to reach at school. But hearing from our students now is that much more rewarding just because we miss them.”

Olivia Dwyer

Library Media Specialist Olivia Dwyer also had to pivot quickly. She went from working faceto-face with around 600 students each week in her

Olivia Dwyer K-3 school to trying to find ways to connect, help teachers with technology needs, check in with parents, and manage her own toddler while working from home.

“So, my days consist of a zillion emails. They range from parents to teachers saying help. I don’t know how to Zoom, you know, just things like that.”

High School Band Director Matthew Page acted quickly when he heard the school was closing.

“And so, I went in and I was just grabbing instruments out of lockers, putting labels on them, saying, who belong to what? Make sure everybody had music,” Page said.

Luckily, Page says his students were already using technology. “We’ve been using this program already called Smart Music, which is an online thing where the kids can go on and put in the piece of music and it scrolls on their screen for them. It records them as they play. So, I can make assignments. They hit record. They like it, it just gets sent on to me so that I’m able to make critiques and stuff like that,” Page said.

Ultimately, educators in Watford City and across North Dakota found a way to make distance learning work. “I have to say that no one went into education to sit by a computer all day, and still missing the kids and the vibrancy of the school setting is a big disappointment,” Rachel Meuchel said. “But I have to say that I’ve never been more proud of my coworkers and my fellow educators across the state. It’s amazing to watch them. They’ve stepped up. They care so much.”

You can find all episodes of the podcast on iTunes, Google Play, iHeart Radio, Spreaker and our website ndunited.org.

Testing is Part of the Answer

Public health units step up in response to the threat of COVID-19

By Kelly Hagen, NDU Communications

Perhaps the best defense against a molecular threat like the COVID-19 pandemic, so small it goes unseen by the human eye, is a similarly invisible force. Those society defenders against pandemics are our local public health units, located across our state. And they are staffed by trained, dedicated professionals like Daphne Clark, public information officer and protection team leader at Upper Missouri District Health Unit in Williston.

“I think the best description of local public health that I have ever heard is that when we are doing our jobs well, no one sees us,” Clark said. “It is only when we fall short that we are seen. Other emergency responders fill important roles that are more visible. Local public health responders are not as visible, but we do fill an equally important role, especially during a public health crisis.”

Clark has worked at UMDHU for more than 16 years. She started her career in public health as a general environmental health practitioner, then moved into becoming an emergency environmental health practitioner. In 2008, she began in her current position. She describes her day-to-day work requirements as promoting and public messaging for her health unit, which serves four counties – Divide, Williams, Mountrail and McKenzie – in the northwest corner of the state. Additionally, she is team leader for the UMDHU emergency preparedness program and environmental health programs.

And her work duties have changed completely since the state’s first reported case of the novel coronavirus on March 11. “All of my time now is spent on COVID-19 response,” she said. “I spend most of my day connecting with partners to work on emergency plans or answering their questions about response.”

UMDHU is one of 28 local public health units in the state of North Dakota. Seven of these units are multicounty health districts like UMDHU and serve wide swaths of geographic terrain. Clark said that UMDHU has an especially strong working relationship

with the Southwestern District Health United, which serves eight counties directly south of their unit. Along with six tribal health units, these public health districts and departments are the “boots on the ground” for the North Dakota Department of Health and are largely responsible for local response efforts.

“We are the ones in the communities who are answering questions and helping to guide local policies,” Clark said. “We have had my team from UMDHU out fit-testing emergency response partners. Fit-testing is necessary for people before they can wear the N95 masks we hear about that medical and emergency response personnel must wear to protect themselves. Our team has fit-tested around 1,000 emergency response personnel. UMDHU also has staff that are assisting the NDDOH Division of Disease Control with COVID-19 case and contact tracking.”

Fit-testing N95 masks for emergency responders, so that they can be protected from the same threat we are all facing today, as well as doing contact tracing of essential workers and supporting them with guidance from NDDOH and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are parts of all the essential, behind-the-scenes planning and implementation of emergency preparedness and response plans during a crisis like this one. And public employees, such as Daphne Clark, go largely unseen during their efforts. Which is the way they feel it should be, but it can still sting, all the same.

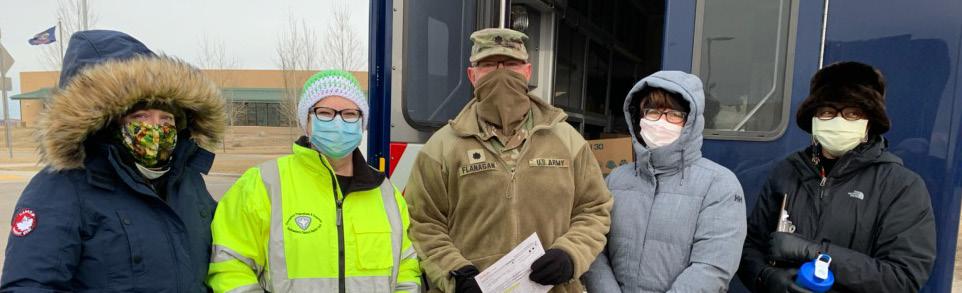

“I’m not going to lie though, when I see other emergency responder agencies getting food deliveries, I do think ‘I like donuts, too,’” Clark said with a laugh. Public health agencies like UMDHU have hosted free drive-thru testing clinics in communities across the state. Working alongside the National Guard, anyone can drive through, get a test directly from their vehicle and have results back in 24-72 hours. One of the first testing sites was held in New Town, and Clark was proud of the role that her agency played in its success.

“We have worked with our partners in the New Town area for years,” she said, “However, having as many partners there working together was something phenomenal to see and be a part of. As many people that were there, everyone took their assigned task and went to work and within a couple of hours, 282 people were tested. It was a great example of what can be achieved when partners and communities come together to work towards one goal.”

Clark urges every North Dakotan to pay attention to this serious situation, and to get their information from reputable sources. “I would encourage them to look to their local public health, North Dakota Department of Health and CDC for information on how to protect themselves and their communities.”

Additionally, she recommends that we all continue to work together to protect as many lives as we possibly can. “This has the potential to go on for a while,” Clark said, “and it is a high-stress situation, so I keep encouraging people to approach others with kindness and graciousness. There will be mistakes made, and we need to look past those to continue our partnerships together to have the best results for our communities.”