7 minute read

The Boomerang Debate

from December 2012

Proposition: The Boomerang is completely and utterly useless

Rupert Murdoch

Advertisement

The Boomerang? More of a 6000€ waste of UCSA money: it’s the committee with the biggest budget, and yet, the most useless one. A few conceited students who fancy themselves journalists produce a joke they call a newspaper. But are they in any way qualified? No. Sure, there’s the Journalism class, but no one ever gets into that, and those who do, never end up writing for the Boomerang.

Those who bother to pick up a copy on their way out of Dining Hall are faced with BS opinions from students who not only lack life experience, but in some cases, also dictionaries. And they can’t even claim they did their best: UCU is demanding, so those “articles” are most likely “composed” five minutes before the deadline. And what about the environment? How many trees have fallen victim to a few students’ delusional journalistic ambitions?

If the Boomerang could at least claim to be independent, fair and balanced, the faults mentioned above may be excused. But it is subject to the censorship of the UCSA Board, which makes fulfilling any kind of watchdog function impossible. Writers must be very careful when reporting on them, which ensures that the skeletons in the UCSA’s closets never emerge. So, if the Boomerang can’t criticize our governing body the way media should, what’s the point?

The people living in Voltaire have an answer: they use it as a doorstop. Which may be as good as it gets, dear Boomerang.

Con

Bob Woodward

Imagine the campus apocalypse to ensue if it wasn’t for Boomerang. College Hall as the ultimate totalitarian power, the UCSA as their secret police, Maarten Diederix as Big Brother – our lives controlled and oppressed. Would you like living in this Orwellian nightmare?

Without journalism, campus democracy would be crushed to pieces. Our writers work day and night to provide you with reads more interesting than those scholarly articles. Their purpose in life is uncovering the truth - in lieu of getting straight A’s or hooking up with that cute exchange guy.

The B oomerang is not afraid to ask the touchy questions, to get you thinking of what you never did before and to expose “public secrets.”

It helps us grow into truly critical and open-minded individuals. Laughter, creativity, and ideas flow freely in the office, when from students, we turn into dreamers, eager to go change the world.

Soon, the reality of getting things done kicks in. Writing, interviewing, editing, re-editing and layout-ing –the making of the Boomerang is like a part-time job.

And even though the fun is enough to motivate the Boom folks, positive side effects abound. Be it a history paper due tomorrow or a unitmate’s essay you were asked to take a look at – you rush through it with ease and passion, realizing that writing and editing have by now become your second nature.

In giving campus a voice, we care too much and work too hard for a few Boom-skeptics to kill the 13-year-old spirit that the Boomerang is.

Is Letting Something Happen the Same as Causing it? Science vs. Religion: Round 2

Eun A Jo

Last month, we had Dawkins and Harris denouncing religion as not only ruinous, but stupid. With an undercurrent of skepticism towards religion, Shermer explored mankind’s belief system: our hard-wired tendencies to seek non-existent truths. Rise of atheism was the common theme, ending with De Botton’s communitarian approach to adopt atheism 2.0.

Now, let’s flip the coin. What do the pious have to say?

Rev. Billy Graham spoke at TED in 1998 (in its earlier stage of development) in a talk titled “Technology and Faith.” Emitting an aura of ages-old stubbornness, Graham speaks of technological advance and its power to change life, humanity, the world. Is technology a panacea? Can it replace the philosopher’s stone? Had we seen the end of technology, will our souls be liberated from evil, suffering, and death?

Graham being one of the most prominent evangelical preachers in contemporary religion, the answers are conceivably predictable. But the contentious idea is still thought-provoking. Reverse the question: Is religion a universal cure? Can it free our souls?

To delve into the problems of society and our apparent lack of solutions, we must ask about the role of each individual. Pastor Rick Warren, in his moving talk “A Life of Purpose” communicates that God’s intention is for each one of us to use our talents to do good. He juxtaposes this with looking good, feeling good, and having the goods, which supposedly drive today’s materialism-infested society.

Now, drifting away from Christianity, the talk “On reading the Qur’an” by Lesley Hazleton marvels at the grace, flexibility, and mystery often overlooked in the holy book of Islam. As a self-identified agnostic tourist, she explores the Qur’an from the perspective of the uninitiated. From linguistic quality to messages that are often misquoted, she debunks our misconceptions of the Qur’an – Don’t dismiss it that easily as a mere source of violence and destruction!

Mustafa Akyol does exactly the same, however from the perspective of an “insider”. In “Faith versus Tradition in Islam” he criticizes that mundane cultural activities such as wearing a headscarf have become directly linked to the faith of Islam. Should the world (the West) see Islam through the lenses of its seemingly absurd traditions rather than its core values? Akyol concludes: “Islam, despite some of the skeptics in the West, has the potential in itself to create its own way to democracy, create its own way to liberalism, create its own way to freedom.”

Find out how this “counter-intuitive” supposition is argued!

For a greater insight to each talk, read the TEDster comments. They can get highly controversial and sometimes even outright offensive, but there are gems in there that make the rough journey worthwhile.

Talks:

Billy Graham “Technology and Faith”

Rick Warren “A Life of Purpose”

Lesley Hazleton “On reading the Koran”

Mustafa Akyol “Faith versus Tradition in Islam”

Tom Honey “God and the Tsunami”

Bob Thurman “We can be Buddhas”

Matthieu Ricard “The Habits of Happiness”

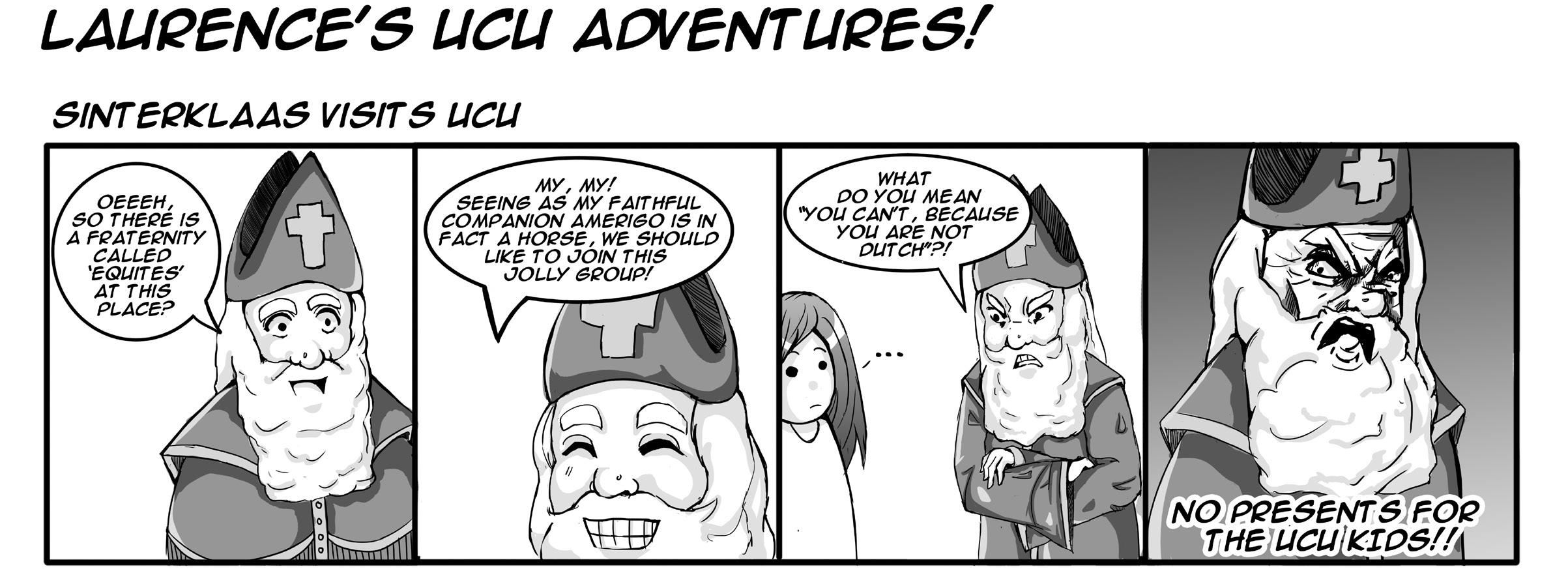

Elena Butti

Since Zwarte Piet caught a flu, Sinterklaas appointed you to help distribute presents on campus. On the magic night of the 5th, as Sinterklaas is riding to UCU on his white horse slightly tipsy from Dutch beer, you realize he is galloping towards a canal. The freezing water is going to swallow all the chocolate letters for UCUers, the horse, and Sinterklaas himself. You still have time to grab the reins and turn the horse away from the canal. In doing so, however, you’ll inevitably run over Santa Claus, who, feeling for Sinterklaas, has decided to distribute his presents on the same night. There are no alternatives: either you let Sinterklaas fall into the canal and the happiness of chocolate-loving UCUers drown with him, or you drive his horse over Santa Claus. The choice is yours. What do you do?

This is the Christmas version of a much more serious ethical dilemma: the moral difference between acts and omissions. Is letting something happen while you could prevent it the same as causing it? This dilemma is often presented through a somewhat cynical thought experiment, which forcefully illustrates the issue. Imagine you witness an uncontrolled train approaching a group of children playing on the rails. Assume you cannot warn the children –the train is inevitably going to kill them. The only thing you can do is change the course of the train, shifting it to another track where an old man, terminally ill, is sitting. This would result in his death. You can stay and look at a group of children dying or actively cause the death of an old man. What do you do?

Some people would choose the latter. This logic is an utilitarian one, advocated, for example, by Bentham and Mill. Its key principle is the attainment of “the highest good for the highest number of people”. The children are many, while the man is only one; the children have their whole life left; while the man will die soon anyways; the children are a potential resource for society, while the old man represents a burden. Other philosophers, like Kant, have instead argued for the sacred and non-negotiable value of human life. They believed that human life is some- thing to which you simply cannot attach a measurable value and weigh it against others. In the train example, since you can’t decide that one life is worth more than another, nor that many are worth more than one, you simply cannot make a choice.

But what is the consequence of avoiding the choice? If you simply lay back and watch, the train will kill the children. Is letting the children die as blameworthy as killing them? Can an omission amount to an action?

This example is, of course, extreme. Most of us, though maybe not all, would probably agree with Bentham rather than Kant, and change the course of the train. But what about a more blurry situation? What if there are three old men on the first track, and only one child on the second track? Can you weigh their lives against each other? Are three lives worth more than one? Is a young life worth more than three old ones? Or is it simply impossible to attach a value to life?

Suppose you decide three lives are worth more than one, and change the course of the train. Are you actually killing the child? After all, you change the course of the train not to kill the child, but to save the three men. Is the death of the child the result of your action, or is it just an undesired consequence?

If you could foresee the child’s death with absolute certainty, your action seems hard to justify. But what if you believed that the child may have the time to jump off the track, so that his death is likely, but not certain? What if it’s only probable? Or very unlikely, but still possible? Does low probability of an unwanted occurrence make you less responsible for it? And does lack of intention take away responsibility?

You didn’t want to cause the child’s death, which was highly unlikely, and you were certain of saving three men: does this make you innocent?

These questions have triggered endless ethical discussions – a good topic for an intellectual afternoon with tea and chocolate letters. Provided that Sinterklaas doesn’t fall in a canal, of course.