3 minute read

Africa is (Finally) in the News Again

from Winter 2022

by Ida van Zwetselaar

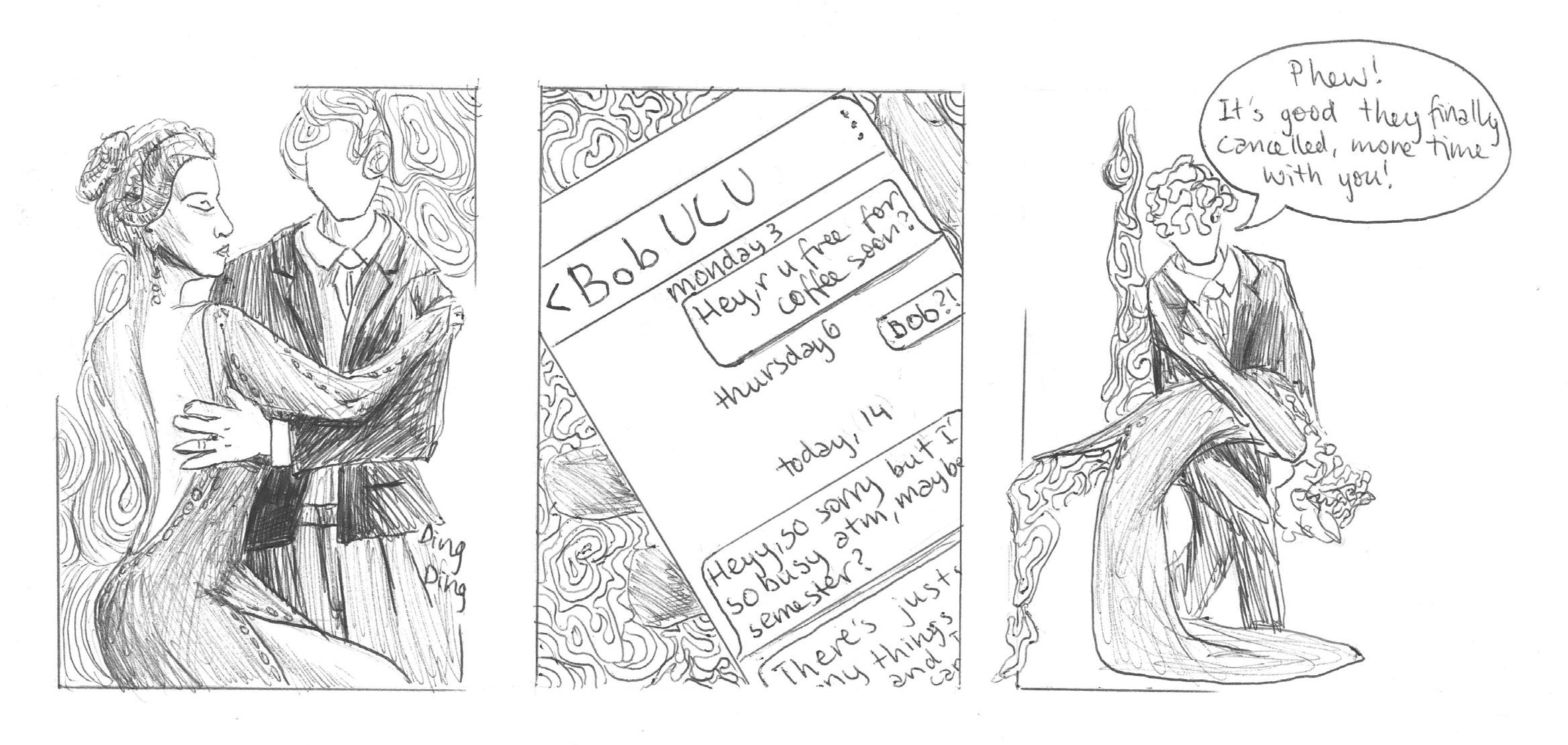

I was looking at my phone exclaiming “Nooo, Kili is burning again!” when someone looked up at me with mild interest in their eyes, so I elaborated. “Mt. Kilimanjaro,” While shoving the photo my family just sent me into his face, “apparently there have been fires on it for days”. A flashback hits of me doing the exact same thing when John Magufuli died and Tanzania suddenly had a female president, or that one time I read about the drastic impacts of global climate change and came across a piece about the summit's rapidly disappearing glaciers. But what’s the point if most people cannot even tell the country apart from its bordering nations, let alone Tasmania, Tunisia, or Transylvania? (Based on true encounters).

Advertisement

I underestimated him though. “Isn’t that, like, the highest mountain of Africa?” he replied, no attention left already. To be clear, it is also the highest free-standing mountain of the world, and embedded in socio-historic, cultural, natural, spiritual, emotional and economic values. Maybe I was a bit too shaken by the thought of my hometown’s landscape going up in flames and wanted to prove something, but with good faith I scrolled straight to the BBC, New York Times, NOS, al-Jazeera, some of those well-known news outlets. Nothing. ‘What the fuck?’ I thought to myself. ‘Where are the live reports that Europe and Northern America received during last summer’s wildfires? And remember when the Notre-Dame was burning?’

I kept checking throughout that week, and one by one, insignificant headlines about the fires caught my eye. However, something peculiar dawned on me. These articles were mostly focused around whether or not the tourists residing on the mountains would be safe, and the fact that firefighting troops struggled to keep the flames under control, so volunteers from the area helped out. More than that, the articles were notably the shortest length allowed for publishing, and all contained identical information: probably the handful that was fed to them by journalists employed at the scene, who likely asked Tanzanian scientists or authority figures for facts.

Isn’t this just a reflection of what they are interested in? The bare minimum?. If it was not for people I know living in the Kilimanjaro region, I would have struggled to find out whether the fires were ever stopped (eventually, they were), what its causes were (remains unknown, but extreme drought and wind fuelled it), what the consequences are (destroyed biodiversity, amongst others). But then again, if it was not for the people I know there, would I have even cared?

A week later, I was surprised to see Tanzania in global news again with a similarly grim story, this time about Africa’s largest lake: “19 dead after commercial plane crashes into Lake Victoria'' (CNN, Nov 7, 2022). The focus was that Precision Air is a common airline for tourists traveling to their holiday destinations, and that the rescue teams were late and busy removing the airplane from the water with help from the local community. A pattern?

British journalists do not report on ‘white on white violence’ when reporting the conflict in Northern Ireland.” Yeah, think about that.

There is a division - or at least an imbalance - in how pressing information about natural disasters, violence, corruption, and other environmental and societal issues gets portrayed between the West and “the Rest”. These countries apparently are not worth as much attention, despite the fact that these stories need a global stage just as badly and are much more dire than what gets screened on most TV news stations every night.

tell the country apart from its bordering nations, let alone Tasmania, Tunisia, or Transylvania?

Well, it seems that popular media nowadays still tend to echo Western Imperial styles of reporting (as was done by missionaries, social scientists and slave traders) when prioritizing and wording articles about the Global South, often adopting a patronising or delegitimizing tone and selecting only the most gruesome stories to tell, in order to affirm a sense of “Otherness”.

One could argue that such sensationalism based on bad news is key to journalism universally. But, as an example from the essay 'The Western Media and Africa: Issues of Information and Images' helps to illustrate, “‘black on black violence’ is a euphemism the Western press used in writing about South Africa in the 1980s, yet

Common to reportage on Africa as a whole is the narrative of hopelessness (with just a sprinkle of primitiveness). News stories from the continent are usually something along the lines of “terrorist attack this”, “drought/flood that”, and “so many million die of [insert disease] here”, “major scandal there”, etc. African landscapes are either seen as full of dangerous animals or landmines, and its people usually as untrustworthy, poverty-stricken or lazy. How do you expect Tanzanian citizens to attempt to personally transgress these stereotypes, if they’re all that’s sold as truth abroad? Even worse, they have little to no control over how this negative image of them spreads.

I don’t need to tell you how powerful modern media and news outlets are at steering this discourse, creating a homogeneous and racist perception of non-white people and regions where catastrophe appears to be their only reality, this is not true. So here is a call for more accurate journalistic coverage of non-western countries where their achievements - not just constant downfall and devastation - are also documented and celebrated. Because if you pick up a copy of, say, The East African, you would notice that there are always (positive) stories that deserve to be shared, without being tainted by dominant, harmful ideologies.