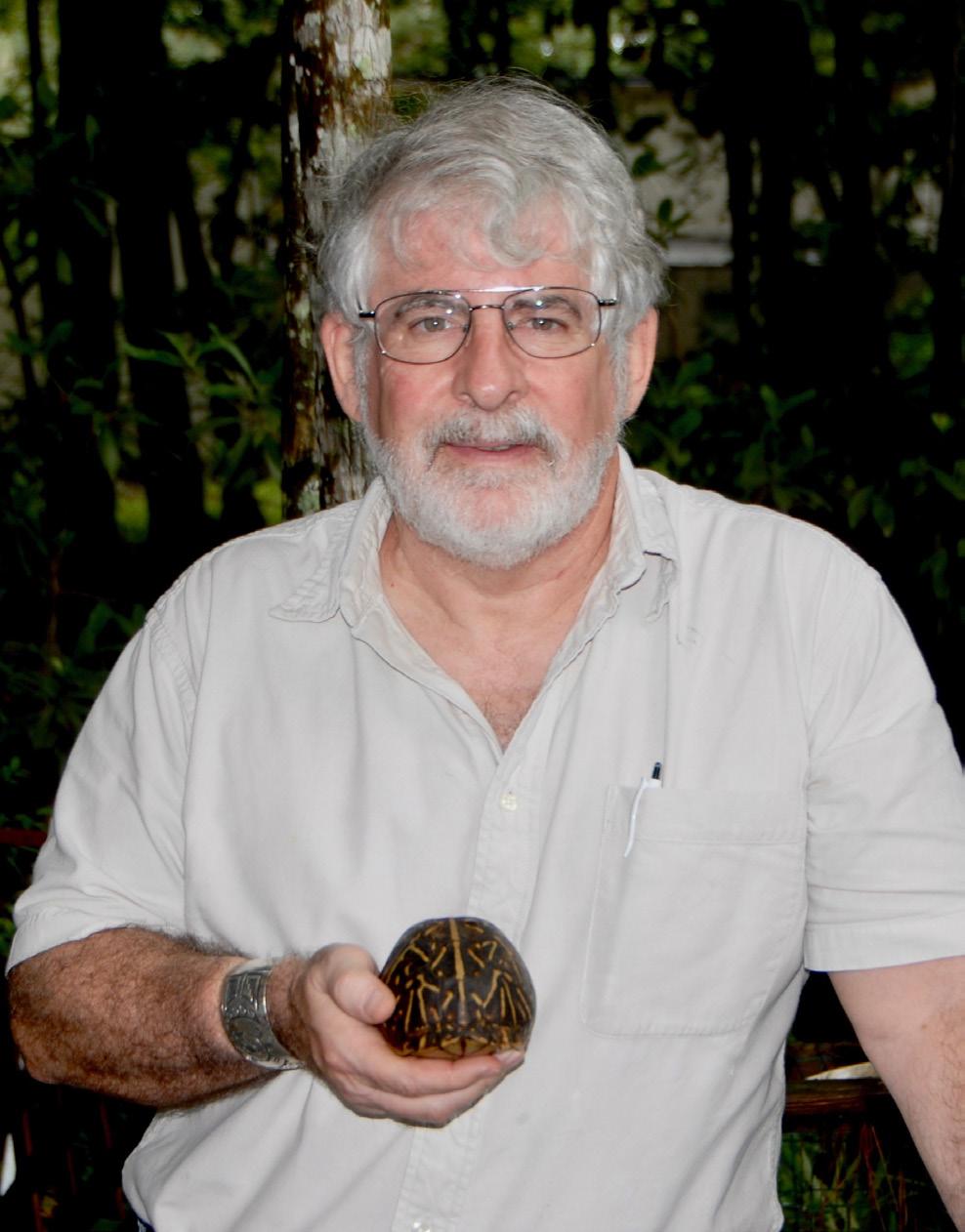

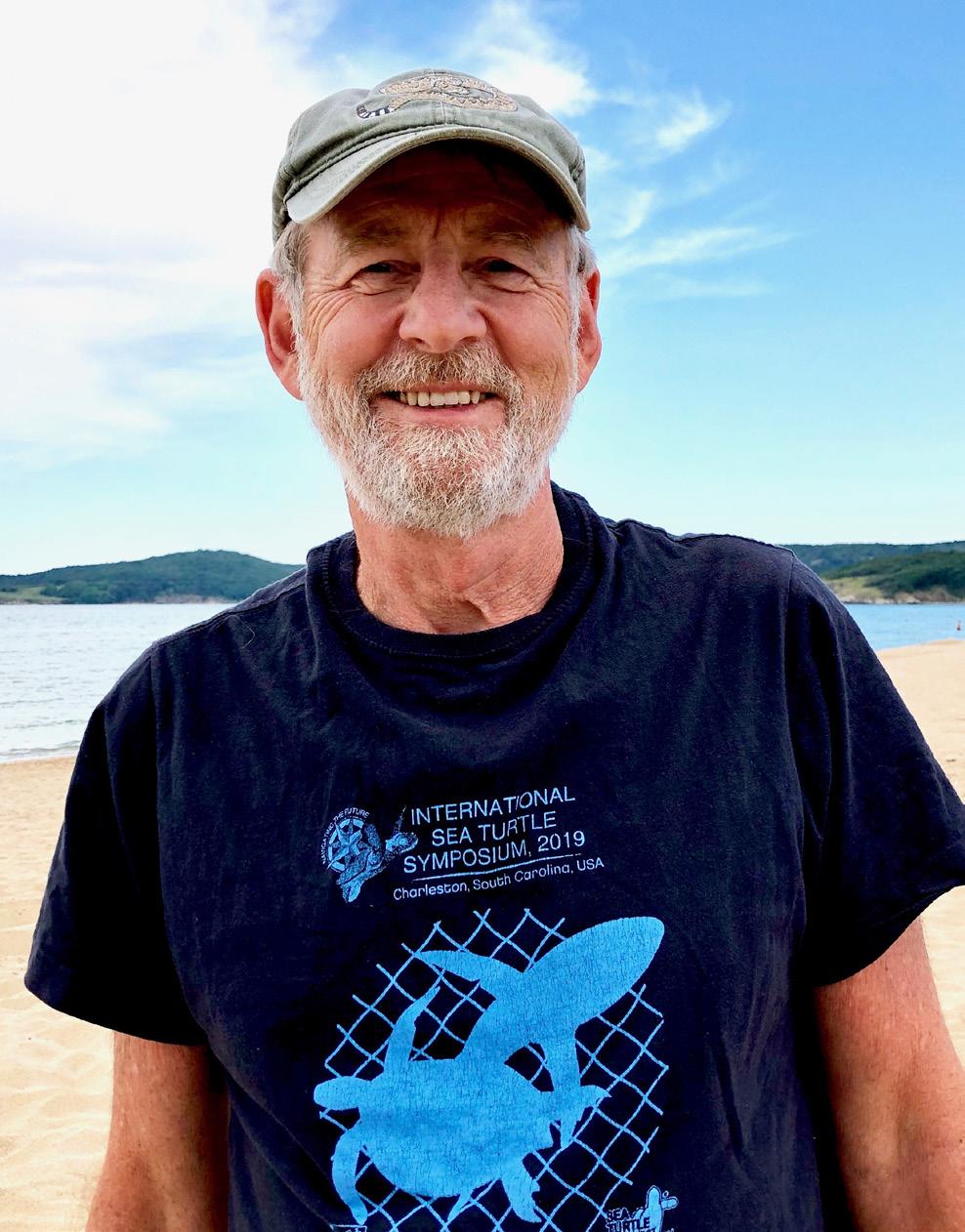

Marc Dupuis-Desormeaux participates in the biannual health assessments of the Red-necked Pond Turtles (Mauremys nigricans) managed at the Turtle Survival Center.

Marc Dupuis-Desormeaux participates in the biannual health assessments of the Red-necked Pond Turtles (Mauremys nigricans) managed at the Turtle Survival Center.

As we applaud our 20th year of tireless dedication to the preservation of our planet’s most vulnerable turtle species, I am filled with gratitude for each and every one of you who stand alongside us in our mission.

Together, we have achieved remarkable milestones, from our successful breeding programs of some of the world’s rarest turtles at the Turtle Survival Center, which celebrated its tenth anniversary in 2023 (see p. 8), to innovative conservation initiatives worldwide. Yet, there is still much work to be done. As a conservation biologist, my journey has taken me from the classroom to the wild, untamed landscapes where wildlife and human coexistence offer sobering reminders to double down on our efforts. The threats facing these ancient creatures persist, demanding our unwavering commitment and innovative solutions.

This magazine serves as a celebration of our progress, a reflection of our shared dedication, and a call to action for the road ahead. Within its pages, you will find stories of hope, resilience, and perseverance.

From Malaysia, where poachers turned Terrapin

Guardians now defend the critically endangered Southern River Terrapin (see p. 44), to Colombia, where genetics chart the course for successful reintroductions of Redfooted Tortoises (see p. 16), to our program in Madagascar, where we are forging the way back home for thousands of confiscated tortoises (see p. 33), each article underscores the transformative impact of our collective efforts.

As we look to the future, let us remain steadfast in our commitment to protecting these irreplaceable species. Thank you for your unwavering support, your tireless advocacy, and your boundless passion for conservation.

With gratitude,

Marc Dupuis-Desormeaux CEO and President

Marc Dupuis-Desormeaux CEO and President

Turtle Survival Alliance is a global conservation organization that works to create a planet where tortoises and freshwater turtles can thrive in the wild. Our science-based initiatives are directed by local leaders, inspiring sustainable, community-based stewardship to prevent extinctions. Where populations cannot yet thrive in the wild, our captive breeding programs preserve opportunities for their future survival.

Our Mission

To protect and restore wild populations of tortoises and freshwater turtles through sciencebased conservation, global leadership, and local stewardship.

Our Vision

A planet where turtles thrive in the wild, and are respected and protected by all humans.

What We Do

• Conservation Breeding

• Field Research and Monitoring

• Rescue and Rehabilitation

• Head Start and Reintroduction

• Training and Capacity Building

• Education and Outreach

• Community Engagement

• Habitat Protection

• Participatory Science

• Advocacy

Devin Welch, TSA-NAFTRG

Alliance North

volunteer reaches out to collect a wild Suwannee Cooter (Pseudemys concinna suwanniensis) in the crystalline waters of Manatee Springs State Park during a scientific research sampling session for our long-term population monitoring efforts there.

On May 11, 2004, Turtle Survival Alliance gained independence— officially registered as a stand-alone nonprofit—after operating under the auspices of the IUCN SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group for the first three years.

It is with great pride and overflowing appreciation that this May we celebrate 20 years of our long-term, science-based initiatives worldwide. Our impact encompasses field research, rescue and rehabilitation, reintroduction, education and awareness, and engaging with communities across the globe. We’ve been on a wonderful journey of passion, innovation, commitment, and growth. These efforts are made possible by dedicated supporters like you.

Together, we’ve made lasting strides, and we hope you’ll continue to join us as we expand our efforts toward a future where every turtle species thrives in the wild. Here’s to the next chapter.

This year, Turtle Survival Alliance welcomed Josh Dale, Michael Gibbons, and Ilana Miller as new members of the Board of Directors. We also bid farewell to esteemed board members John Iverson, Vivian Páez (recipient of the 2022 Behler Turtle Conservation Award), and Satch Krantz as they conclude their terms. A special acknowledgment is extended to John Iverson, whose transformative contributions have left an indelible mark on our organization through his financial acumen and generous support. We are profoundly grateful for their service in advancing our mission to ensure the survival of turtle species worldwide.

Josh Dale is a finance professional based in New York City. Having spent the past decade focused on the renewable energy sector, he is now the Head of Energy Transition at Rabobank, where he leads a team that supports companies and projects which are dedicated to bringing the energy industry to net zero emissions as soon as possible. Josh has been a passionate outdoorsman and lover of animals for as long as he can remember, making the conservation work at the Alliance a perfect fit.

Michael Gibbons is the Vice President of Corporate Strategies for Trident United Way, and has spent 15 years in nonprofit leadership. Prior to his career in nonprofits, Mike spent 15 years in journalism as a reporter, editor, and executive, and still contributes to a column part-time. Passionate for turtles from an early age, he began helping on his father’s turtle studies as a small child, and has continued to this day taking part in numerous amphibian and reptile volunteer initiatives.

Ilana Miller is a lawyer based in New York City with over 14 years of experience as a business litigator and general counsel. She currently serves as deputy general counsel at Selfhelp Community Services, a nonprofit organization dedicated to providing affordable housing and essential social services to vulnerable and elderly New Yorkers. Throughout her years of practice, Ilana has been actively engaged in pro bono matters, and committed to advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. Ilana, a lifelong animal lover and outdoor enthusiast, thanks her mom for fostering her love for reptiles. She has numerous memories of rescuing injured animals and aiding wildlife sanctuaries and is grateful to be joining our conservation efforts.

This year, Turtle Survival Alliance experienced growth, expanding our team by introducing new roles and inviting skilled, enthusiastic individuals to join our staff. This strategic initiative aims to allocate additional resources, time, and expertise towards our mission to protect and restore wild populations of tortoises and freshwater turtles. The following staff began in the timeframe of October 1, 2022, to September 30, 2023.

1

Natalia Gallego-García, PhD Director of Conservation Genetics

“Driven by a passion for conservation, I’m on a mission to empower conservation through genomics and chart a successful future for endangered species around the world.”

Natalia Gallego-García is a devoted conservationist and geneticist committed to utilizing cutting-edge molecular tools to steer global conservation efforts for threatened species. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Biology, a Master’s degree in Ecology and Evolution with a specialization in computational biology, and a Ph.D. in Biology with a focus on conservation genomics. Before assuming the role of Director of Conservation Genetics at Turtle Survival Alliance, she served as a Postdoctoral Researcher at UCLA. During her time there, she conducted research into the effects of habitat loss and population fragmentation on Dahl’s Toad-headed Turtle, and delved into unraveling the intricate species complex of the Red-footed Tortoises in South America (see p. 16).

2

Ratri Lertluksamipun Director of Development

“My mission is to unearth and nurture a fascination and admiration for turtles that lives

in all of us, even if it’s yet to be discovered.”

With more than 10 years of experience in nonprofit administration, donor relations, and fundraising, Ratri has advanced missions for organizations in higher education, the arts, and healthcare industries. She was previously the Senior Alumni & Constituency Relations Officer for the University of Southern California School of Architecture and served as the Associate Director of Event & Corporate Fundraising at P.S. ARTS. Ratri is passionate about conservation, sustainability, and helping those in need—be it animal or human. In her role she provides opportunities for individuals, institutions, and corporate partners to fulfill their philanthropic intentions while supporting conservation action.

3

Abigail Bush Office Manager

“I am greatly inspired by the unwavering passion and tireless dedication that I have witnessed in conserving these amazing creatures. I am excited for the future of the organization to see what other feats we can accomplish.”

4

Elena Duran Communications Coordinator

“Using my experience and skills gained through my work in the nonprofit sphere to

advocate for a thriving future for turtles and tortoises has been a highlight of my career. I’m fortunate to be a part of this passionate, driven team of conservationists.”

5

A.J. Fetterman Chelonian Keeper

“It is a dream come true to be working to maintain the beautiful collection of turtles and tortoises at the Turtle Survival Center. I look forward to the future and am excited about my opportunity to aid in our goal of zero turtle extinctions.”

6

Makayla Peppin-Sherwood Grants Manager

“I’m so grateful to contribute to such an important mission. Empowering conservationists to protect these amazing turtles and tortoises is an honor and a privilege.”

7

Nita Yawn Chelonian Keeper

“The opportunity to spend hands-on time with critically endangered turtles has been both rewarding and humbling. Being part of a team who values and respects the lives of the creatures we share this planet with is what makes all of the hard work and effort worth it.”

“In celebration of the Turtle Survival Center’s tenth anniversary, we are delighted with the progress that the Center has made in fulfilling and exceeding its captive management goals. With mild winters and warm summers, the subtropical region in which Cross, South Carolina, is located makes it ideal for the management of assurance breeding colonies for numerous species of endangered turtles. There, the Center has become a hub for research, innovation, and education. From collaborations with academic institutions and local student involvement to hosting and sharing knowledge with experts around the world, the Center is where conservation meets compassion.

As founding donors, we take pride in the Center’s plans to expand its assurance colonies and to bolster its genetic bank to maintain healthy populations. We believe that these efforts are vital to the shared goal of our Foundation and Turtle Survival Alliance for preventing turtle and tortoise extinctions. It stands as a testament to our lifelong commitment to conservation. At this critical time for biodiversity, we renew our pledge to safeguard these efforts, ensuring a future where turtles and tortoises thrive in the wild.”

-Alan and Patricia Koval Foundation

The

Jay Meredith Turtle Survival Center has produced nearly 100 hatchling Indochinese Box Turtles (Cuora galbinifrons) since 2016.In the Lowcountry of South Carolina, about 40 miles from the closest city and located off a long, winding, gravel road, sits a gated property. Behind the unassuming chain-link fence and imposing black gate, inconspicuously warning people to keep out, lies a world unseen by most passersby. There are no signs or flourishes hinting at the remarkable activity within.

This sight is familiar as I pull up to the gate and, with a swipe of my access card, wait for the automated voice to say, “Wel-come. Chel-sea.” The gate opens, and just around a slight bend, a shiny new sign finally alerts visitors to what waits beyond—the Turtle Survival Center—a vibrant hub of turtle conservation. This wondrous 51-acre property safeguards some of the world’s most endangered species of turtles and tortoises from extinction while doubling as a protected area for native turtles and other wildlife.

This year, the Turtle Survival Center (TSC), or the Center, as it’s often called, celebrates a decade of operation and success since “opening its doors,” though not publicly, as Turtle Survival Alliance’s ex situ breeding facility. Today, I’m sitting down with Cris Hagen, the Center’s Director, and Clint Doak, Assistant Curator, to chat about the facility and their anniversary celebrations. As a fellow Turtle Survival Alliance employee, I’m familiar with the Center but excited to delve deeper and share its incredible ten-year history.

Turtle Survival Alliance (the Alliance) was founded in 2001 as an IUCN/SSC partnership network and working group for sustainable captive management of tortoises and freshwater turtles and became an official tax-exempt nonprofit organization in 2004. Beginning with a very small budget, and no paid employees for many years, turtles were managed by volunteers through taxon management groups at multiple facilities. The need for a committed group of employees and a dedicated base of operations became evident to manage these critical assurance colonies.

In 2012, the Alliance began a fundraising campaign, and the following year purchased the property that is now known as the Turtle Survival Center. Unfortunately, converting the property from a crocodile conservation center, building new enclosures through severe weather and ex-

Nickie Stone, © Garden & Gun

Nickie Stone, © Garden & Gun

tremely wet and muddy conditions, was not a walk in the park. The tenacity, innovation, and do-it-yourself engineering needed in these first months laid the groundwork for facing and overcoming the many obstacles that come with running a world-renowned conservation center in subtropical, coastal South Carolina, and is the literal foundation on which the Turtle Survival Center is built.

Today, the TSC is a flourishing center with the purpose of maintaining genetically diverse colonies of critically endangered turtles for future generations and the hopeful restoration of populations in the wild; a living ark, or genetic bank, for species that currently have little to no chance of survival in their natural habitats.

“We have species that are disappearing from the wild and the only way to secure their existence is to maintain captive colonies—our purpose is to do that in a scientifically managed way,” says Cris.

As the Center’s Director, Cris manages the population of animals at the Turtle Survival Center but also those that are part of a larger collection plan. The Alliance coordinates its work with Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) institutions, other conservation organizations and educational institutions, trusted individuals, and Turtle Survival Alliance

members to extend the population beyond the gates of the TSC. This large-scale effort helps to meet population and genetics goals and also keeps the last proverbial eggs of a turtle species from being in one basket. As of this year, the Center houses 28 species onsite, with 20 of those actively being managed as part of the larger collection plan.

The Center cares for a diverse array of turtles, most of which are considered Critically Endangered, with a few priority species that are thought to be functionally extinct— and possibly completely extinct—in the wild, and some that have never been seen by turtle biologists or researchers in their native habitats. Turtles like the Zhou’s Box Turtle (Cuora zhoui), McCord’s Box Turtle (Cuora mccordi), Rote Island Snake-necked Turtle (Chelodina mccordi), Vietnamese Pond Turtle (Mauremys annamensis), Red-necked Pond Turtle (Mauremys nigricans), and Yellow-headed Box Turtle (Cuora aurocapitata), are only surviving because of the

highly specialized conservation work being done at the few facilities like the Turtle Survival Center.

Also residing at the facility are representative ambassadors for species that have major conservation success stories, like the Burmese Star Tortoise (Geochelone platynota), whose comeback from the brink of extinction is nothing short of extraordinary.

Over the past ten years, the Turtle Survival Center has become a beacon of hope for imperiled turtle species, fostering genetically healthy populations and contributing significantly to global species conservation and preservation.

The Center stands out as a driving force in turtle survival across the globe. “Turtles play a vital role in our ecosystems, and we’re stepping up in a large-scale capacity to save them—we’re trying to be a catalyst for change,” says Clint, who considers the Center to be a leader among others of its kind for its grand-scale science-based conservation efforts.

The role that the Center plays in the future survival of some of the world’s most endangered turtles is vital. And when you take into account the revolving door of obstacles the facility has had to overcome, including intense weather conditions, staff transition and retention, and limited space and resources, the rate of success has been remarkable.

When asked how they’re measuring success, the metrics were broken down into four categories: expansion of the colony, maximizing genetic diversity, creating pathways for returns to the wild, and shared knowledge and training.

Tracking and measuring the number of turtles in the collection, and increasing the population numbers in a scientifically-managed way.

The number one way the Center ensures the survival of the world’s most endangered turtles is by continuing to build the ark. Each turtle hatchling breeds new hope for the future of their species. Cris says that successful breeding “indicates that we know what we’re doing, and it’s one of [the] ultimate goals of a conservation management breeding center.”

It also means that they’re creating an F1 population, the first generation, and step, in creating a genetically diverse population of hardy, captive-bred animals that will ensure the future of this population.

The TSC has seen such incredible breeding success and exponential growth that the current infrastructure is now limiting the population. “We’re at a point right now where we can’t really continue to grow the population anymore,

until we grow the facilities,” says Cris.

The Center staff can boast more than just population growth. The facility has been able to unlock the secrets for some of the most historically difficult-to-breed species, like the Indochinese Box Turtle (Cuora galbinifrons) and the Sulawesi Forest Turtle (Leucocephalon yuwonoi). This knowledge can then be shared with other facilities, field country programs, and conservation partners.

Ensuring that the genetic potential of the population is maximized by monitoring genetics and keeping studbooks.

The Center’s commitment to genetics research is equally as impressive as its population growth. Through population genomics work with experts like Natalia Gallego-García, Turtle Survival Alliance’s first Director of Genetics, they’ve been able to make the most informed breeding decisions—i.e., who to pair with whom—to maximize gene diversity of the captive population over multiple generations and foster healthy offspring.

Every one of the nearly 800 turtles housed at the Center

From left: This Rote Island Snake-necked Turtle (Chelodina mccordi), hatched at the Center, may one day be part of a program to repatriate this species to its native habitat; The Yellowheaded Box Turtle (Cuora aurocapitata) was among the first species to reproduce at the Center, like this one hatched in 2015; The Center has had prolific success in breeding the McCord’s Box Turtle (Cuora mccordi), a species presumed extinct in the wild. This is one of 42 hatchlings produced since 2017.

represents a vital genetic link for the future. This year alone, multiple genetic analyses have been conducted to optimize breeding moving forward. This approach has identified some cryptic hybrids in the population and, with kinship analysis, has also helped to make informed determinations of individual pairings for breeding.

To maximize diversity, bloodline exchanges routinely take place with other facilities in the larger managed collection. The Center has even conducted bloodline exchanges with facilities as far as Europe.

Measuring the impact the TSC and the Alliance have on its peers by tracking the number of people trained and/or hosted for research.

The trials and successes at the Center in the last decade have become teachable moments. The knowledge that TSC staff have gained over the years has led to a working knowledge of biology, husbandry, and population management and they’ve been sharing their knowledge with others.

Locally, the Center has offered facility tours for colleges, hosted volunteer groups, and run an internship program, all aimed at inspiring the next generation of turtle conservationists. Additionally, they’ve presented at conferences and participated in local community outreach and school career days. This creates a pipeline of passionate individuals who can one day lead the charge in protecting turtles from extinction.

On a broader scale, the TSC has shared its expertise with other Turtle Survival Alliance projects and programs, as well as partner organizations and peers, promoting best practices for turtle reproduction and species survival across the globe.

This year, the Turtle Survival Center finally launched a long-awaited course on Turtle Biology, Conservation, and Management, co-sponsored by the AZA Chelonian Taxon Advisory Group. Held on TSC grounds, the course brought together some of the field’s most renowned experts for a unique exchange of knowledge and experience. This dedication to education and collaboration lies at the heart of the Center and Turtle Survival Alliance’s mission.

Determining if species can be successfully restored or reintroduced to the wild, and implementing a plan of action.

A prime example of this is the Rote Island Snake-necked Turtle (Chelodina mccordi), a Critically Endangered species native to the islands of Rote and Timor in Indonesia. Hatchlings born at the Center are carefully monitored and given the best chance of survival. Some will remain for breeding purposes, while others may be sent to zoos and aquariums accredited by the AZA to contribute to their Species Survival Plans. Most excitingly, some individuals may eventually be part of a Wildlife Conservation Society repatriation program, where they will be prepared for reintroduction back to their native habitat on Rote Island.

This is Turtle Survival Alliance’s ultimate goal, to see turtles once again thriving in the wild. The Turtle Survival Center’s breeding triumphs, genetic advancements, collaboration, and education, have paved the way for future success and for the future generations of turtles.

A decade of research, breeding, and hatching has resulted in astonishing results: 950 hatchlings produced from 27 species and subspecies, over 750 chelonians currently residing at the Center, 530 total turtle habitats among indoor and outdoor complexes, 4,200 square feet of construction among three climate-controlled buildings, and $4.2M raised for the Center since its inception.

So far, the Turtle Survival Center and its staff have accom-

plished goals above and beyond expectations. Imagine what can be accomplished in the next decade and beyond.

“As we look ahead to the future of this facility… our work is far from done,” says Clint.

And with the fluidity of a living collection plan, there are still so many options for the direction of expanding the collection. “We can look into the future, broadening our species outside Asia and North America. We’d like to bring in mainland African species, Madagascan species, and [help] the AZA SAFE: American Turtle Program with confiscations of North American species,” says Clint. “With the right resources, the possibilities are endless.”

Acknowledgments: AAZK Detroit, Alan and Patricia Koval Foundation, Andrew Sabin Family Foundation, Anonymous, The Arthur L and Elaine V Johnson Foundation, Barbara B. Bonner Charitable Fund, Bob Olsen, Brian Bolton, California Turtle and Tortoise Club, Columbus Zoo and Aquarium, Cris Hagen, Dallas Zoo, David Shapiro, Dennis Coules, Dennler Family Fund, Detroit Zoo, Felburn Foundation, Gregory Family Charitable Fund, Houston Zoo, Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens, John Iverson, Mazuri Exotic Animal Nutrition, Nashville Zoo at Grassmere, Oklahoma City Zoo & Botanical Garden, Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo & Aquarium, Post and Courier Foundation, Riverbanks Zoo & Garden, Roy Young, Saint Louis Zoo, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, Sedgwick County Zoo, Tennessee Aquarium, The Tides Foundation, Tracks Data Solutions, Virginia Zoo, Walter Sedgwick, Wildlife Conservation Society/Bronx Zoo, William and Jeanne Dennler, Zoo Atlanta, and Zoo Med Laboratories.

*Contributions of $5,000 or more since January 1, 2013

Contact: Chelsea Rinn, Turtle Survival Alliance, Turtle Survival Alliance, 5900 Core Rd., Ste. 504, North Charleston, SC, USA 29406 [crinn@turtlesurvival.org]

Jordan Gray

Jordan Gray

Employing Genetics to Optimize Conservation Efforts

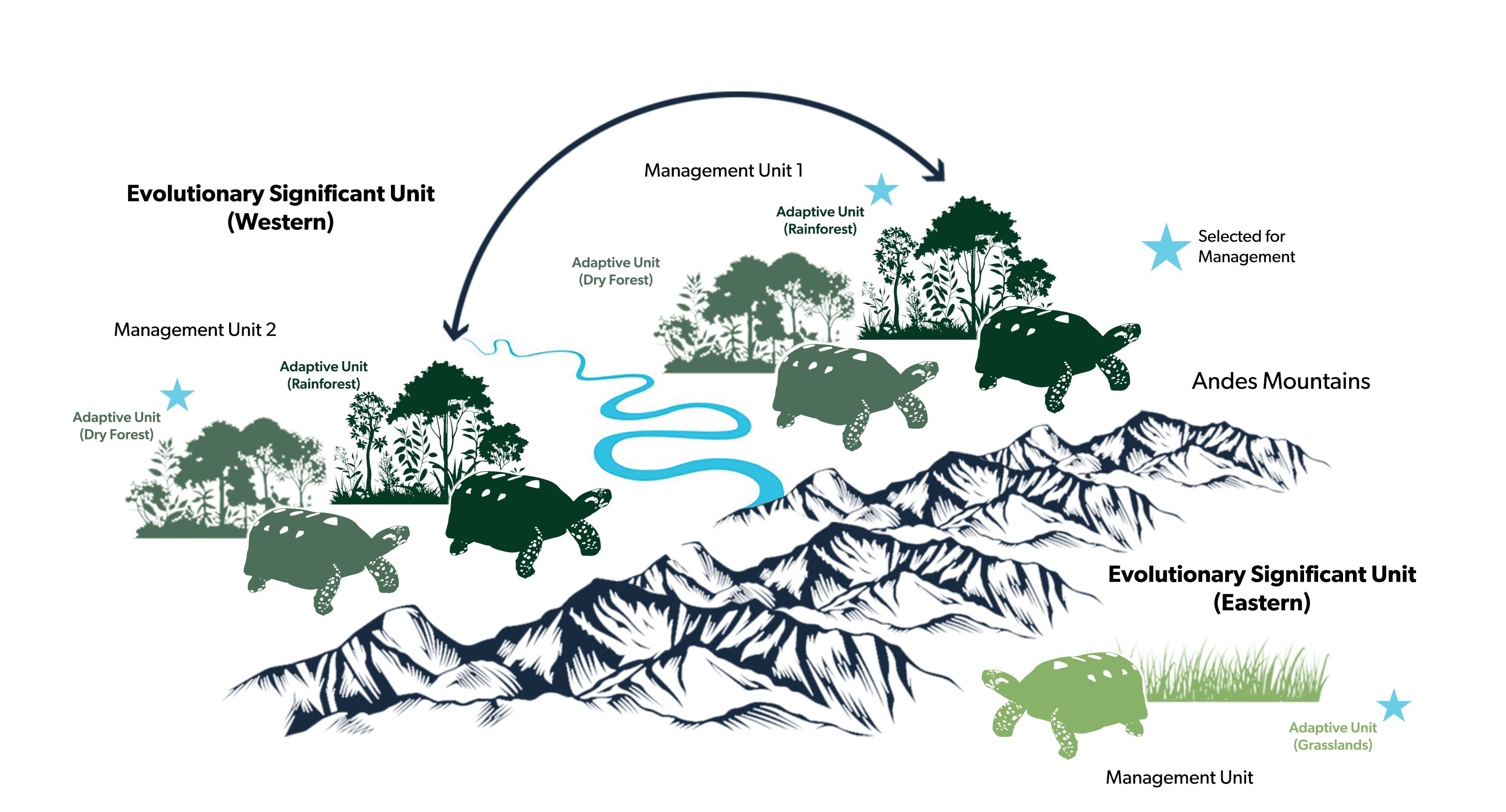

by NATALIA GALLEGO-GARCÍASuppose you have limited resources, and you wish to protect a species that spans a large geographic area. Where will you implement your conservation actions? How can you ensure that these efforts extend beyond the local population to impact the species as a whole? Those are the questions that genetic data can answer. Genetics can help direct resources where they can have the greatest impact. How, exactly? Well, it allows us to understand if the species is divided into neighborhoods or populations—known as Conservation Units (CUs)—and to identify the key ones to protect.

There are different types of CUs, and a key one is the Evolutionary Significant Unit (ESU). These are groups of individuals that are separated either by geography or because they can’t easily mate with each other. They have their own unique evolutionary histories and special traits that help them survive in their specific environments. Some-

Red-footed Tortoise (Chelonoidis carbonarius) exhibits remarkable morphological variation throughout its range, leading scientists to believe that it may not be a single species, but rather a complex of multiple species that have not yet received proper taxonomic recognition.

times referred to as subspecies, ESUs are genetically and ecologically so different that we manage them separately. An ESU may encompass one or more Management Units (MUs). Often referred to as populations, these are independent groups that have very few individuals moving in or out of their local area. We use these units to delineate the minimum scale for conservation, as management actions implemented in one MU won’t have an effect on another. Sometimes, MUs are located in different environments, which can lead to individuals developing unique traits to help them survive in those specific places. When this happens, we call them Adaptive Units (AUs), and we make sure to take those differences into account when planning conservation strategies.

Let’s see how CUs are used to design conservation strategies. The Red-footed Tortoise (Chelonoidis carbonarius) is a species with one of the largest ranges in the world, spanning approximately 2 million square miles (5,100,000 km2) and encompassing all countries in South America except for Ecuador. This species exhibits remarkable morphological variation throughout its range, leading scientists to believe that it may not be a single species, but rather a complex of multiple species that have not yet received proper taxonomic recognition. But here’s the tricky part: figuring out exactly how many species of Red-footed Tortoises there are and where they all live takes time. And while scientists are busy working on this task, these unnamed tortoise groups could be slipping through the cracks, getting closer and closer to extinction without

anyone even realizing it. This is when delineating CUs becomes handy, as it allows managers to acknowledge these distinct groups for the sake of conservation, even if they haven’t been formally classified yet.

This approach was adopted in Colombia, where two distinct lineages of the Red-footed Tortoise are found, each located on opposite sides of the Andes Mountain Range. Recent studies have shown that these groups aren’t just different in where they live—they’re genetically and ecologically unique. On the western side of the Andes, tortoises live in the forest, while their counterparts on the eastern side dwell in grasslands. These tortoises are now adapted to their specific environments and cannot interbreed as the Andes act as a reproductive barrier. Because of these significant differences, scientists designated these eastern and western groups as ESUs. Within the eastern ESU, a single MU was identified, while the western ESU comprised two. But wait, there’s more! Further genetic studies showed that tortoises living in the rainforest had evolved special traits to deal with the humid conditions, while those in the dry forest had their own adaptations. So, within each western MU, scientists identified smaller AUs based on these habitat-specific traits.

Based on this fine-scale delineation of CUs, the conservation plan to save the Red-footed Tortoises in Colombia was shaped. The goal? To protect as much genetic diversity as possible while minimizing the number of units, streamlining conservation efforts. In the east, the focus was directed towards conserving the single MU, representing the entire

ESU in that area. In the west, conservation efforts were targeted at two distinct Adaptive Units: the dry AU from one management unit and the rainy AU from the other.

This strategic approach narrowed down conservation actions from an entire country to just three sites! And there’s more; it also helped plan out relocation efforts, like moving tortoises to areas where they have been wiped out. Why is that important? Because relocating tortoises isn’t as simple as it sounds. We’ve got to be careful not to mess things up by moving animals between different ESUs or AUs. That could lead to some serious problems, like the tortoises not being able to adapt to their new environments or struggling to survive. To avoid these risks, translocations were restricted to occur only within each ESU and between equal AUs— dry to dry and rainy to rainy. Genetics is a powerful tool to optimize conservation strategies. CUs are but one example; the possibilities are endless.

Acknowledgments: This work received financial and technical support from the Wildlife Conservation Society - Colombia, the Shaffer Laboratory at UCLA, and the Biodiversity and Conservation Genetics Group at the National University of Colombia. We thank Tim Gregory for his generous donation that made this research possible.

Contact: Natalia Gallego-García, Turtle Survival Alliance, 5900 Core Rd, Ste. 504, North Charleston, SC, USA 29406 [ngallego@turtlesurvival.org]

As a child, I was constantly fishing. Always observant, I quickly hid when boats filled with fishermen came near. I clearly remember one group in a fancy Jon boat. They had an odd way of fishing using ropes. Two men would shake the ropes as if they’ve hooked a giant fish and the others would then jump in the water. When those who jumped in returned to the boat, I heard a loud “bang” as if a rock fell into the hull. When I looked more closely, I saw a large turtle. I winced as the men shouted in triumph. Here I was witness to the poaching that has led to the dramatic decline of the Central American River Turtle (Dermatemys mawii), known locally in Belize as the Hicatee.

It was also during my youth along the Belize River that I vividly recall sitting on a cliff as I watched a huge, dark brown shell surface. I heard a sharp sound as it quickly released air and then torpedoed back down to the river’s

depths. The Hicatee is a unique species with a complicated physiology. At the time, I didn’t understand why they weren’t on land and always thought they were mysterious. I now know that the Hicatee is so adapted for an aquatic existence that it has evolved to draw water into its mouth and absorb the dissolved oxygen from it before expelling the water through its nose, allowing them to stay submerged for a prolonged period of time. The Hicatee is not only mysterious, but an incredible example of evolution.

Animals in the wild today don’t seem to behave like they did when I was ten; they appear to act more wary of human presence. Now, on a clear day, if I see a Hicatee, I stay very still when it comes up to breathe, because any sign of movement causes it to disappear.

It’s not just the animals’ behaviors that have changed, so too has the landscape. The forested trail I walked as a kid no longer exists; it has been replaced by a corn field. Here and now, there are no trees until I reach the riverbank, a ribbon of green riparian forest barely twenty feet in width hugging the water. What I see are large pipes releasing effluents into the river, banks degrading, garbage accumulating, herons and cormorants caught in nets and fishing line, the water a less vibrant green, and animals missing on the trails I once enjoyed. Observing all these losses breaks my heart. I wonder, will there be sustainable efforts to restore these ecosystems and the animals that depend on them?

Working with the Belize Foundation for Research and Environmental Education (BFREE) has allowed me to develop a mindset of conserving Belize for future generations. My work at BFREE is focused on the Hicatee Conservation and Research Center (HCRC), which was created in partnership with Turtle Survival Alliance in response to catastrophic declines in Hicatee populations due to increased and unsustainable harvesting for human consumption.

At the HCRC, we facilitate and promote research on the biology and ecology of Hicatee, focusing on such aspects as breeding and nesting behaviors, dietary needs, growth rates, as well as pathogens and parasites. Through captive breeding efforts at the Center, we have hatched and raised over 1,000 turtles and released over 500 into the wild. We offer volunteer opportunities and training associated with our facility, and host meetings and symposia to help further collective knowledge on the species.

BFREE has established Hicatee Awareness Month—the largest outreach campaign for the species. We engage young minds and the general public via events, media, and school programs to create awareness and encourage community action. We are also gearing up for the launch of our

field research team, where we will offer opportunities for others to collaborate and assist in the field work once we get started. Together, we will gather the data needed to better understand the species and its current distribution in the wild. Our ultimate goal for the Hicatee is to see it once again thriving in self-sustaining populations in its native habitat.

As for me, I won’t stop dreaming of the day when I return to the cliff of my youth and see my beautiful Belize as it once was and can be again: rich and lush in all its natural glory.

Acknowledgments: We would like to acknowledge Turtle Survival Alliance, Zoo New England, David and Jean Hutchison, the Alan and Patricia Koval Foundation, Wildlife Conservation Society, and two anonymous donors for their ongoing support of this project.

Contact: Barney Hall, Belize Foundation for Research and Environmental Education, P.O. Box 129, Punta Gorda, Belize [wildlifefellow@bfreebz.org]

During our university years, fate intertwined our paths and forged a friendship that endures to this day. Since 2017, this friendship has grown even stronger thanks to our shared commitment: the conservation of our beloved Chaco Tortoise (Chelonoidis chilensis).

The Chaco Tortoise stands as an emblem of Argentinian Patagonia’s unique biodiversity. As the southernmost continental tortoise species globally, found from southwestern Bolivia to northern Patagonia in Argentina, its conservation holds paramount importance. The Patagonian population is seriously threatened by habitat modification by livestock (mainly cattle), predation by exotic predators (feral dogs and

wild boars), illegal local pet trade, bushfires, and climate change. Additionally, the Chaco Tortoise’s eggs have an unusually long incubation period of 10 to 16 months, leading to prolonged vulnerability of nests and reduced recruitment of new animals into the population. So, since 2017, we have been tirelessly monitoring this endangered species, unveiling the multitude of threats it faces in its habitat.

Chief among these threats is the Pomona Water Canal, a 121-mile (195-kilometer) predominantly concrete structure snaking across the Patagonian plateau to supply water to the cities of San Antonio Oeste and Las Grutas. Despite its utilitarian purpose, the canal has inadvertently become a death trap for numerous native species, including the Chaco Tortoise. The smooth, high, and steep walls of the canal render escape all but impossible for animals drawn to its waters, leading to tragic drownings.

Realizing the urgent need to address this issue, we embarked on a multifaceted approach. With support from Turtle Survival Alliance, Fundación de Historia Natural Félix de AZARA, Turtle Conservation Fund, and the Rufford Foundation, and the collaboration of more than 20 volunteers and scientific researchers from across the country, we decided to launch rescue missions to save tortoises

impact on native fauna.

Strategic placement of camera traps in some sewers along the canal revealed a diverse array of species utilizing it as a wildlife pass, from wild cats and foxes to armadillos and skunks. However, conspicuously absent were the tortoises, underscoring the likelihood that the tortoise population has possibly remained separated for more than 50 years. This long separation prevents genetic exchange between the sides of the canal, leading to ecological and genetic consequences, such as a reduction in genetic diversity.

With a clear understanding of the challenges at hand, we formulated a meticulous plan of action. Wildlife surveys would be conducted along the canal during the tortoises’ active season, enabling the mapping of vulnerable hotspots and the precise timing of conservation efforts. Moreover, innovative barrier designs and escape structures would be deployed and rigorously tested onsite to mitigate the canal’s adverse impacts on wildlife.

Crucially, the team recognized the importance of community engagement in achieving their conservation objectives. Through a concerted awareness campaign, we aimed to rally local support for the protection of this iconic species and its fragile habitat. By fostering partnerships with canal administrators, wildlife authorities, landowners, and public officials, we sought to mobilize collective action toward sustainable solutions.

In essence, the efforts to mitigate the impact of the Pomona Water Canal on Chaco Tortoises and native fauna exemplify a holistic approach to conservation. Through scientific research, rescue operations, habitat management, and community involvement, we endeavor to secure a brighter future for the unique biodiversity of Argentinian Patagonia.

certain death. Over two seasons, hundreds of dead animals were removed from the canal, and more than 90 tortoises were successfully rescued.

However, the rescue efforts extended beyond mere extractions from perilous situations. Through monitoring tortoises using radio telemetry, researchers gained invaluable insights into the behavior, health, movement, and feeding habits of the tortoises. Remarkably, we even had the privilege of witnessing three females laying eggs.

Yet, the challenges persisted. The Pomona Canal not only posed a direct threat to individual animals but also acted as a physical and ecological barrier, impeding the natural movements and dispersal of wildlife, including Chaco Tortoises, across the region. Recognizing the gravity of the situation, we set out to comprehensively assess the canal’s

Acknowledgments: We thank Tim Gregory and Turtle Survival Alliance for logistical and financial support, and Fundación de Historia Natural Félix de Azara, Turtle Conservation Fund, and Rufford Foundation for funding. We would like to give special thanks to our volunteers: Aye, Leto, Ro, Kenya, Gabi, Lucia, Paula S., Paula A., Belén, Juan, Cami, Oliver, Santi, Juana, Agos, Jesi, Maxi, Ren. We extend additional thanks to Milton Perello, Maxi García, Sebastian Dalgalarrondo, Damian Cardeli, Germán Ferro and, of course, to the ranchers Peco Gastaminza, Martín Echave, Coco García, and Estela Nuñez.

Contact: Erika Kubisch, Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas - Centro Regional Universitario Bariloche, Universidad Nacional del Comahue, R8402AGP San Carlos de Bariloche, Argentina [ekubisch@comahue-conicet.gob.ar]

Swift conservation actions needed for the world’s smallest turtle

by TAGGERT BUTTERFIELDIt was Summer 2018 when I first got the news of a “A Distinctive New Species of Mud Turtle from Western Mexico.” I was sitting at my computer at the Chamela Biological Station in Jalisco, Mexico, just two and a half hours south of where this new species was described from in Puerto Vallarta. In this paper, familiar authors, but a very unfamiliar turtle was made known, the Vallarta Mud Turtle (Kinosternon vogti).

Not only did this newly published paper claim that this was a novel species described to science, but that it was one of the smallest species of its genus, and somewhat spectacularly, the males had a conspicuous bright yellow scale on their noses. My first thought was “this cannot be real” and that the yellow nose must be some kind of infection or abnormal growth that I have seen several times on the Mexican Spotted Wood Turtle (Rhinoclemmys rubida perixantha), a species that I had spent the last three years surveying in Chamela. I have also been to Puerto Vallarta many times on my way to Chamela, and it seemed to me more than likely that there was so much contamination in the city that perhaps the yellow nose was a result of a contaminate.

Intrigued and in disbelief, it wasn’t until 2019 that I finally had time to spend a few days in Puerto Vallarta and try to trap this new species of mud turtle. I was especially excited because I was going to be able to include this species as part of my PhD project that aimed to compare the morphology and ecology of different turtle species.

The first locality that I tried to trap this distinctive new species was the type locality, or the locality of the first individual used to describe the species. To my surprise, this locality was directly in front of a shopping mall on a very busy street in Puerto Vallarta. The potential canal where it could have been found was lined with cement and bone dry. So, if I couldn’t put traps in this canal, where was I going to find this turtle?

I made my way upstream along the canal to a river where I found water access behind some houses where there was an apparent homeless encampment. It did not seem like a safe place to leave traps, but I made a deal with two of the individuals living in the encampment that if they watch my traps, I will give them each 100 pesos the next

day. They assured me that the traps would be safe. Their word, though, did not give me confidence. I could barely sleep that night, imagining that all my traps would be stolen, but sure enough, at 7 AM, when I went to check the traps, the two individuals were still there, wide awake, and had been keeping an eye on the traps all night. There were no turtles in any of the traps, but I still had the traps, and a deal was a deal, so I paid each individual 100 pesos.

Five years, 600 trap nights, and 40 localities later, this first experience next to the river encapsulates what it has been like to sample for this species: stress, paranoia, and uncertainty that my traps would be stolen. Indeed, on three occasions I have had traps stolen, and to this day I still have trouble sleeping on nights that I have traps out in Puerto Vallarta or the surrounding areas. But, at least we now know

the dire situation this turtle is in. On my first three visits to Puerto Vallarta in 2019 and in 2021, I did not trap the Vallarta Mud Turtle. Not only was it extremely exhausting to track down landowners and get the necessary permissions to trap almost any locality in the valley, but with each unsuccessful trap night the situation looked more grim. I grew extremely concerned that this turtle might have disappeared before we even got the opportunity to learn anything about its biology, and I had a hard time imagining where this turtle could possibly exist if it was not in the numerous localities where I had tried to trap it.

Today, we know that this species is restricted to very specific habitats and that these habitats comprise less than 49 acres (20 hectares). To make this worse, Puerto Vallarta and its surrounding areas are one of the fastest-growing areas in Mexico and one of the most popular tourist destinations in the world, making land more valuable than gold. One acre of land costs upwards of a million dollars.

So will the Vallarta Mud Turtle go extinct in the wild? All of the habitats where the Vallarta Mud Turtle persists are surrounded by highways or busy roads and are destined for development. While there is a slim chance that land will

be able to be purchased to save this species, it seems most likely that the future of this species will be restricted to small lagoons that will require maintenance by the city of Puerto Vallarta or developers. It’s our desire that both the city and these developers are committed to seeking viable solutions for monitoring and preserving the species throughout the construction process and well into the future. Thanks to the University of Guadalajara and the Guadalajara Zoo, we know that individual turtles will at least continue to persist in captivity into the near future, but conserving its habitat is an uphill battle. But, it’s a big battle that we are willing to fight for this tiny endemic turtle.

Acknowledgments: John Iverson, Tim Gregory, Fabio Cupul-Magaña, Armando Escobedo-Galván, Rodrigo Macip-Ríos, locals of Puerto Vallarta, Alejandra Monsviás-Molina, Abel Domínguez-Pompa, and Turtle Survival Alliance.

Contact: Taggert Butterfield, Estudiantes Conservando la Naturaleza [taggertbutterfield3@gmail.com]

Diving into conservation with the North American Freshwater Turtle Research Group

by CHELSEA RINN

There’s something undeniably special about turtles. Maybe it’s their prehistoric origins, seemingly having walked the earth since the dawn of time. Or perhaps it’s something simpler—an almost universal fondness for them that defies age, background, or status. Simply put, people love turtles.

Attend any Turtle Survival Alliance outreach event, and you can witness the magic firsthand. The minute a turtle emerges, a crowd gathers, eyes widen with wonder and curiosity, hands reach out to touch, and a shared appreciation for these animals ripples through the crowd, creating a sense of togetherness and stories that last well after the event is over.

As one of my colleagues says, “Everyone has a turtle story.” My own story began with the familiar Eastern Box Turtles (Terrapene carolina carolina) of my Virginia childhood, and then working at Zoo Knoxville, a veritable hub for turtle breeding and conservation, where my passion deepened. Then, I joined Turtle Survival Alliance, where I’ve not only learned about many fascinating species I didn’t know existed, but have been able to experience them in the wild.

A little over a year ago, my growing deck of turtle stories became a little more exciting as I attended my first North American Freshwater Turtle Research Group (NAFTRG)

survey in Florida, where I got to see these new-to-me turtles in their natural habitats for the first time; species like the Suwannee Cooter (Pseudemys concinna suwanniensis), whose striking aquamarine eyes match the springs that we find them in.

These surveys are performed to gather data on turtle populations in fragile ecosystems, and every sample is different depending on the landscape. My first survey was a two-for-one weekend survey that the attending volunteers fondly call “Fanatee,” a dual sample of both Manatee Springs and Fanning Springs State Parks. The structure of NAFTRG springs surveys is simple: first, a group of volunteers snorkel to catch turtles; then, they process the turtles and gather data.

Though I didn’t know what to expect that first trip, I made it through without incident and caught five of the almost 200 turtles documented that weekend. The experience was incredible. The cool water was revitalizing and I was in complete and utter wonder as freshwater turtles zoomed across the center of the spring run to take cover in the vegetation. Since then, seeing turtles thriving in their natural habitats continues to be my favorite thing to do.

Just over a year later, we’re back, for my fourth survey at the same place.

Exhausted from our annual conference in Charleston,

our team piles into a fifteen-passenger van and heads south to Florida to participate in the summer Fanatee population survey. We’re a more diverse group than usual, with visitors from Texas, California, and even Argentina joining the regular crew.

After taking medicine for motion sickness, the trip itself is a blur for me, but once we arrive, we go into hyperdrive quickly setting up camp, and preparing to jump into the water for the first sample of the weekend.

Though tired, we have a successful evening catching turtles, gathering data, marking them, and releasing them back into their homes. The experience of swimming to exhaustion followed by the methodical process of weighing and measuring turtles becomes like a meditation. I’m still not the fastest swimmer or the most skilled turtle catcher, but I love this work and the impact I know it’s making on the future of these animals.

The next day we make a grocery run, and as we return, we look for a tortoise burrow that someone had told us may be at the front of the park. Just past the gate, someone in the van says, “There it is,” and there, in the median in front of the guard shack, is a tortoise burrow and a proud Gopher Tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) standing at attention in front of it. I am excited, naturally, because I’ve never seen one before.

But as I look around the van at my coworkers, and friends, people who have worked with and studied turtles for years, every single one is on their feet, hunched over seats, with their faces practically pressed against glass trying to get a glimpse of this majestic little guy.

And this moment is a testament to the unifying power of turtles, that even seasoned researchers, accustomed to working with turtles, can’t resist the thrill of seeing one in its natural habitat. This moment, these stories, and these animals connect us. They remind me of the importance of what we do, protecting turtles and ensuring their continued survival.

This NAFTRG survey site in Florida is just one of the multiple sites where Turtle Survival Alliance is working in North America and only a fraction of the impact the Alliance has on protecting turtles across the globe.

Acknowledgments: Fanning Springs State Park, Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Florida Parks Service, Manatee Springs State Park, and Joleen Barry.

Contact: Chelsea Rinn, Turtle Survival Alliance, Turtle Survival Alliance, 5900 Core Rd., Ste. 504, North Charleston, SC, USA 29406 [crinn@turtlesurvival.org]

New findings traverse state lines

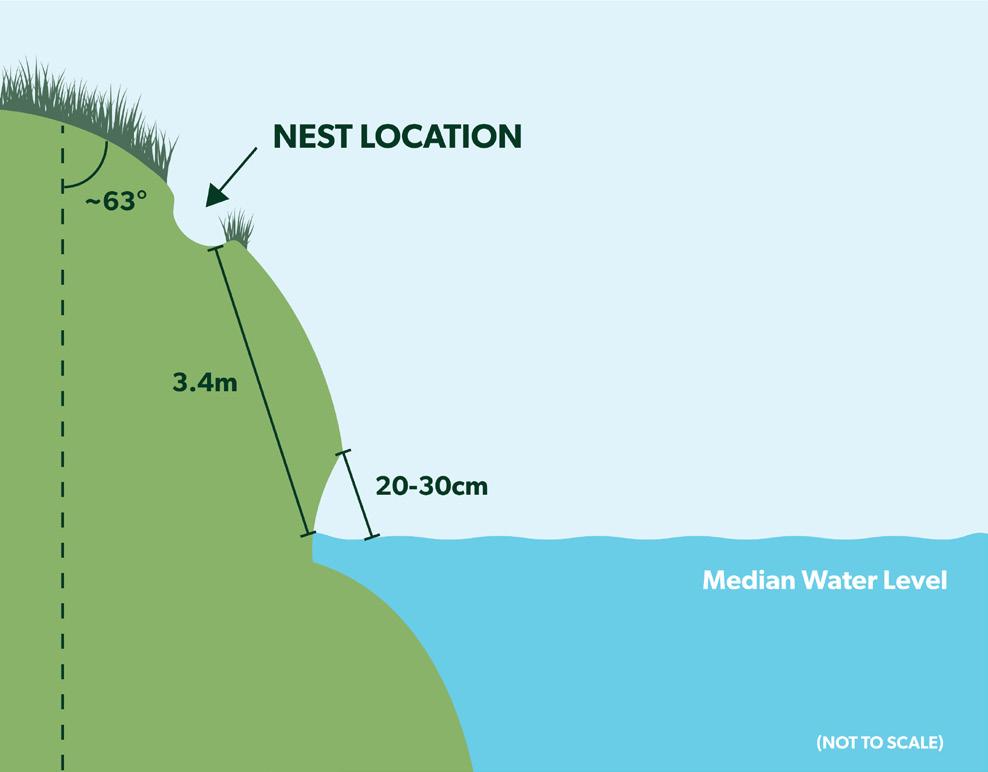

by ELENA DURAN, JORDAN GRAY, AND HOLLY HEWITTHow did she manage to climb up there? Gazing upwards, Eric Munscher, Director of the Turtle Survival Alliance-North American Freshwater Turtle Research Group (TSA-NAFTRG), Dr. Gabriella Sosa of the Buffalo Bayou Partnership (BBP), and Kelly Norrid from Texas Parks & Wildlife Department could only wonder how a female Alligator Snapping Turtle (Macrochelys temminckii), an animal not designed for vertical climbs and heavy with eggs, had managed to make her way up a very steep bank to nest.

The turtle had been spotted by David Rivers, a long-time captain of the BBP’s custom vacuum boat, and although he knows these waterways like the back of his hand, he was shocked to see this turtle perched precariously on top of the enormous bank. After taking video he alerted Dr. Sousa and two days later he took the group back out to the site.

Eric is baffled at how the turtle accomplished climbing that bank to make a nest because the water levels were not high, and the angle from the water to where the nest was located is incredibly steep. This unlikely sight is also significant for Eric’s research: this is the first Alligator Snapping Turtle nest site he has documented in the urban Houston, Texas, area. Finding this nest in an urban situation is very significant from a conservation perspective—the area is seemingly suboptimal for nesting as it is highly tidal and brackish. This suggests the need for further study as this use of atypical habitat can help us understand where and

how females are using areas along highly impacted bayous to nest. To do this, the team will affix satellite transmitters to female Alligator Snapping Turtles in their study area, which will provide precise locations of their activities, including nesting spots.

It’s important to gain a better understanding of how the turtles are using this habitat because it’s in a volatile area that floods, and floods often, depending on the quantity of rainfall received. Despite these conditions, the turtles have adapted to these continuous changes in their environment and have been using Houston’s urban waterways

Two of the 89 hatchling Carolina Diamondback Terrapins (Malaclemys terrapin centrata) recorded by Team Terrapin in 2023 make their way to the salty waters of a North Florida estuary.

Two of the 89 hatchling Carolina Diamondback Terrapins (Malaclemys terrapin centrata) recorded by Team Terrapin in 2023 make their way to the salty waters of a North Florida estuary.

to their benefit. The knowledge gained will help to inform further conservation measures and riparian zone use and planning—especially as they relate to municipal flood control initiatives—fallen trees, log jams, and root balls are all flood hazards, but removing them could also be very damaging to essential Alligator Snapping Turtle habitat.

This work is the longest running research on this species in the country and there’s yet more to do. This April, the team will begin trapping and tagging turtles in the San Bernard River, an area that extends 10-15 miles beyond the accepted, historic range of the species. This research shows promise as Eric learned that local fisherman have encountered three Alligator Snappers in this river before. Even more exciting, based on their descriptions, one of these turtles appeared to be a juvenile, which means there could be a breeding population of Alligator Snapping Turtles in the San Bernard that little is known about.

Alligator Snapping Turtles are resilient and adaptable, just like Eric and the team on their quest to study, research, and protect this vulnerable species. Next year will tell if more turtles have nested in other unlikely places and help to conserve those places amidst the metropolis that is the United States’ third largest city—an unlikely refuge for an abundance of Alligator Snapping Turtles.

Far to the east, on Florida’s northeastern Atlantic coast, a windy, choppy day isn’t enough to keep Tabitha (Tabby) Hootman and Team Terrapin from setting out to see if they can find female Carolina Diamondback Terrapins (Malaclemys terrapin centrata) in the process of nesting. They spot two females heading to nesting sites and decide to wait before attempting to gather all the information that they can about them. While waiting for them to complete their nesting, they spot another, then another, and another after that. Running towards them, Tabby and the team are able to capture and process six females, gathering vital information in this one golden encounter.

As the North Florida lead for TSA-NAFTRG, Tabby’s work focuses on Diamondback Terrapins, the only turtle in the world to live exclusively in brackish water. The field work entailing nest and female spotting, documentation, monitoring, and deterring predators has grown in leaps and bounds in the last year, drawing many new volunteers passionate about helping this threatened species thrive. When the program started, there were just six volunteers, but by the end of last year’s season, they had 47. The season for Diamondback Terrapin field work in Northeast Florida is from April 1 to September 30, and requires daily attention. More eyes in the field allow for greater opportunity for turtles to be counted and other crucial information to be gathered. Thanks to this boost in volunteerism, the number of nests counted has risen to well over 800 the past two years.

The progress realized is due in no small part to the

heightened level of community interest and the ability to amplify this important work. Spreading the word through local universities, zoos, and public interest groups has resulted in an upwelling of volunteers all wanting to do their part for turtles, even when time-consuming and grueling. Such was the case when 33 volunteers ranging in ages from ten to 80 came out and spent six hours under the blazing sun to remove a mountain of garbage from the island. And, on another occasion, one of the youngest volunteers found a group of hatchlings emerging from a nest, exclaiming, “I never want to leave; this is the best moment of my life!” There’s no age restriction on loving turtles.

The success of fieldwork comes down to the ability to find the animal you are studying in the wild—no easy task when meticulously combing the beach for small tracks leading to well-hidden nests. Thanks to the dedication of Team Terrapin, this season, 47 females were collected and equipped with PIT tags (Passive Integrated Transponders), small microchips the size of a grain of rice that allow for the identification of individual turtles. This method led to the discovery of a female that nested on the same part of the beach three times last year, lending important findings on female fidelity to nest site selection.

The tireless devotion of Tabby and Team Terrapin toward a vision where Diamondback Terrapins are thriving in Northeast Florida makes this research and conservation initiative for this unique turtle possible. This upcoming season promises more success, and more engagement with the turtle-loving community.

More than 800 miles north of Florida’s sandy beaches, wildlife biologists Gary* and Laura* slog through muck

that’s practically swallowing their field boots. Battling barbed, cutting, and poisonous plants, biting insects, and ticks, they’re on the lookout for a secretive resident of New Jersey’s wetlands: the Bog Turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii).

Despite its name, the Bog Turtle, the smallest turtle in the U.S., lives in various shallow-water habitats like fens, meadows, bogs, and swamps. These habitats are threatened and fragmented, just like the one in New Jersey that Gary and Laura are exploring.

Located on protected land, the Bog Turtle populations that Turtle Survival Alliance and the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection are studying live between two wetlands separated by a young forest. The wetlands were once connected, but changes to the landscape and hydrology separated them, fragmenting their populations and threatening their existence. Sadly, this is common in the realm of the Bog Turtle. The team aims to learn about each of these micropopulations, and if rejoining them through habitat management can amplify their numbers.

In mid-September, as Gary and Laura navigate the dense wetland, they expect a routine day. With nesting season over and little turtle movement in the summer, their work has become somewhat monotonous. But, armed with knowledge of the turtles’ favorite individual locations, they head to a familiar spot where an adult male has taken up residence, wondering if they even need their tracking devices. Habit prevails, and Gary switches the device on.

The strong beep of the transmitter, picked up by their receiver, confirms the presence of the turtle—and another that they aren’t expecting. Nestled below the tussock is the well-grooved mahogany-colored shell of an unmarked

turtle. Gary picks up the new discovery and realizes that based on the number of growth rings, the turtle is just under seven years old—a subadult—and the first young turtle to be found during our study there.

Finding a new turtle is always exciting in fieldwork, but this discovery carries more significance for this Bog Turtle study. A young turtle’s presence indicates successful recruitment of new individuals into the population. With less than 20 turtles known at this wetland complex, every new turtle is a reason to celebrate. One small inconspicuous find brightens the future for this endangered species. With continued research efforts and future habitat management, perhaps in the coming years, Gary and Laura’s vigorous efforts under challenging conditions will be rewarded with the sightings of more young Bog Turtles.

The work of our United States projects and the volunteers that lead them paints a picture of dedication, perseverance, and hope in the face of environmental challenges and underscores the importance of grassroots conservation efforts, research, and habitat protection for many species of freshwater turtle in need of champions.

Acknowledgments: For their support and contributions to these projects, we would like to thank the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department, Kelly Norrid, Memorial Park Conservancy, SWCA Environmental Consultants, TC Energy Corporation, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection–Fish and Wildlife–Endangered and Nongame Species Program, Brian Zarate, Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Florida Parks Service, Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens, Allison Conboy, Wade Smith, Ali Flisek, and Friends of Talbot Island State Parks, and Eric Munscher, Tabitha Hootman, and Joe Pignatelli for their contributions to this article.

Contact: Eric Munscher [emunscher@turtlesurvival. org]; Tabitha Hootman [thootman@turtlesurvival.org]; Joe Pignatelli [jpignatelli3@gmail.com], Turtle Survival Alliance, 5900 Core Rd., Ste. 504, North Charleston, SC, USA 29406

*Last name omitted by request.

“The Maryland Zoo is a founding member of the Association of Zoos & Aquariums’ Saving Animals

From Extinction (AZA SAFE): American Turtle Program whose goals are to conserve and expand wild populations of imperiled native turtles, including the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta), and develop a pathway for confiscated turtles to contribute to effective conservation efforts. We hope that Maryland Zoo’s Wood Turtle head start project will provide a model for returning confiscated turtles to the wild through their progeny in conservation breeding programs.”

- Dave Collins, Leader, Turtle Survival Alliance/ AZA SAFE: American Turtle ProgramEarly in 2020, just as the world was shutting down due to the emerging COVID-19 pandemic, Maryland Zoo’s Conservation Department was looking for opportunities to open itself up to new partnerships. The department was already involved with studies of native species, including the use of radio telemetry to track Eastern Box Turtles (Terrapene carolina) on our campus—

which is surrounded by old growth forests, wetlands, and natural streams—to understand more about their range and habitat usage. Having built up considerable knowledge and experience, we were excited to work with other species.

That’s when fate intervened in the form of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Maryland Zoo works with the Maryland DNR on multiple projects including on Black Bears, Snowy Owls, Bog Turtles, and other species. In this instance, Maryland DNR was in possession of female Wood Turtles rescued from an illegal collector in Upstate New York. Genetic testing pinpointed the turtles’ native region to a watershed in Western Maryland, so they came to our zoo for medical screenings while their future was considered. While healthy, it was determined the animals could not be released into the wild. They had spent too much time around other species and no one wanted to risk unintentionally introducing a turtle or herpetological disease into a declining wild population.

Instead, DNR was able to locate an appropriate male that was introduced to the confiscated females to begin a head start colony. It all came together quickly and, by the spring of 2021, we were underway. About that same time, we were incubating an egg and rearing a hatchling from a female Wood Turtle that was hit by a car within the same watershed. After rehabilitation, the mother was released back into the wild. We nurtured the hatchling with minimal human contact in a secluded area of our animal hospital. She was given a pool with an environment tailored to Wood Turtle development—with sediment, a strong water current, and foods like live worms to hunt.

After about a year, that hatchling was ready to survive these conditions in the wild. It was also large enough to hopefully thwart predation by raccoons and to carry a ra-

dio transmitter that DNR and our zoo successfully used to track the animal’s movement in its new environment. Our teams made regular visits to the release site for more than a year, monitoring the hatchling’s growth, weight, and overall health.

With this successful pilot study, we were confident in our headstarting and tracking protocols for this important species. And, just in time. By the fall of 2022 there were six head start hatchlings from the confiscated parents. The hatchlings were kept out of brumation to grow over the winter under the same conditions as the initial headstarted animal. In about a year, they would be ready for release.

Each turtle we can place in the wild is critical to the population. This small, charismatic species is vulnerable to the pet trade and habitat loss due to agriculture and human development. They are slow to reproduce, taking a long time to reach sexual maturity, and experience high hatchling mortality.

In addition to a forest with a cool, clear, fast-flowing stream, an ideal location for release would have a declining natural population. It also had to be remote enough that Zoo and DNR teams could regularly monitor and track the animals without drawing unwanted attention from poachers. Together, with the Susquehannock Wildlife Society, our zoo and DNR found a good release site in central Maryland.

From left: A Maryland DNR technician holds a wild Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) during a health survey with the Maryland Zoo; A Wood Turtle hatchling bred at the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore, the first cohort of the confiscated females; Maryland Zoo associate veterinarian Dr. John Flanders gives a health examination to a juvenile Wood Turtle prior to transmitter placement and release.

Once the hatchlings were large enough, about 100 grams in size, they were microchipped, outfitted with radio tracking devices, and successfully delivered to their new homes.

The collaboration between a DNR and our zoo provided a perfect opportunity for the original confiscated Wood Turtles to contribute reproductively, bolstering wild populations that have experienced striking declines. Key to the program’s long term success is treating each population holistically, not just focusing on the animals we release but addressing the collective threats they’re facing as a colony. There is no magic fix. It takes all of us, working together to help this amazing species reclaim its place in the Maryland wilderness.

Acknowledgments: The Maryland Zoo would like to thank Beth Schlimm and Brian Durkin from Maryland DNR and the Susquehannock Wildlife Society for their collaboration on this project, as well as Mike Evitts, Maryland Zoo Senior Director of Communications, for article assistance.

Contact: The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore, Conservation Department, 1 Safari Place, Baltimore, MD, USA 21217 [conservation@marylandzoo.org]

Empowering communities through tortoise conservation

by RICK HUDSONIn 1991, I made my first trip to Madagascar with the late John Behler and others, which became the trip of a lifetime. I was drawn to return to this enchanted island in 1994. During those trips, I was able to spend time with all four of the endemic tortoises, three of them in their habitat. Madagascar captured my heart and soul, and I developed an abiding love for the people and wildlife of this imperiled wildlife paradise. This passion continues today and will be with me for the rest of my life.

Four years later, I returned to the island nation for the 2008 IUCN Red-listing workshop, where the statuses of the Radiated, Spider, and Flat-tailed tortoises were elevated to Critically Endangered, joining the Ploughshare as being at a high risk of extinction. Two years following that important workshop, Turtle Survival Alliance launched a tortoise conservation program, and since 2010, I have returned to Madagascar one to two times per year to keep the program moving and respond to the growing threats.

Significant growth occurred for Turtle Survival Alliance’s Madagascar program in 2023, driven largely in response to intensifying poaching pressures and the need to establish community-protected areas for tortoise reintroduction. While we continue to focus on getting more of the ~23,000 Radiated Tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) prepared for release back into the wild, we have—out of necessity—expanded our enforcement activities to include more staff and improved our collaboration with the gendarmes (police). Likewise, the scope of our overall Confiscation to Reintroduction Strategy has expanded and includes the following elements, all interrelated and all critical to the long-term future of the Radiated Tortoise in the wild: 1) Rescue/rehab and Reintroduction; 2) Community Engagement; 3) Enforcement; and 4) Protected Area Management.

Though Madagascar has four species of endemic tortoises—all Critically Endangered and facing extinction, and all in need of Alliance attention—the vast majority of our resources are directed to the Radiated Tortoise because of the huge number that we are managing in captivity. While we have an ever-expanding role with Spider, Flat-tailed, and Ploughshare tortoises, this article focuses on the Radiated Tortoise. We intend to bring you updates on the other species in future issues.

Early in the history of the Madagascar program, it became evident that while we were dealing with the symptoms of the illegal tortoise trade—tortoise seizures—it was necessary that we also work on the enforcement side of the issue. We hired our first Enforcement Coordinator in 2013 and began building the capacity for enforcement at both the local and regional levels, working with both gendarmes and judicial officials.

While enforcement has been a cornerstone of this program for years—bringing many poachers to justice and disrupting trafficking networks—this program got a substantial boost from a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service grant. A twoyear project entitled Reversing the decline of Madagascar’s critically endangered Radiated Tortoise: a paradigm shift in reducing tortoise trafficking was supported with $75,000 from that grant and got underway in late 2022. The paradigm shift refers to an improved working relationship between the Alliance’s network of local informants who are committed to combating tortoise poaching and the local gendarmes who are officially in charge of enforcement actions. This shift resulted from an unfortunate incident that exposed corruption on the enforcement side while bringing to light the value of well-intentioned local informants in combating both corruption and poaching. The incident helped both parties realize the benefit of sharing intelligence and cooperating openly, overcoming distrust and bridging an important gap in the enforcement chain.

Seizing on this opportunity, our proposal implements the following objectives: 1) Improve communication and establish trust among stakeholders by utilizing District Tortoise Coordinators (DTC) to coordinate tortoise anti-poaching activities; 2) Expand the network of qualified informants by providing essential communication and transportation equipment and by supporting the prosecution of identified suspects; and 3) Improve prosecution rates by following arrest cases at the judiciary level and facilitating the presentation of evidence and witnesses. The goal of this approach is to foster collaboration between primary stakeholders in two districts, Beloha and Tsihombe, in the Androy region. Two DTCs have been hired and are helping ensure that a bridge between communities and law enforcement officials is established and anti-poaching activities are coordinated. This strategy is helping to curtail tortoise poaching by more effectively detecting and apprehending traffickers.

The underlying weaknesses—other than corruption—in the enforcement process in southern Madagascar is that gendarmes are based in the few towns that dot this rural landscape, are poorly funded, and have no capacity for

patrolling. Poaching camps can operate with little fear of being caught unless there is an active network of informants that are willing to confront or report them. Our informants are provisioned with motorbikes, bicycles, and cell phones so they can notify gendarmes of illegal activity. Even then, the Alliance is responsible for providing transportation to the gendarmes and facilitating their work.

In 2023, the first full year of this project, the two DTCs began to actively recruit trusted villagers to work as informants. DTCs convene quarterly meetings to coordinate communications among informants and enforcement officials and an effective anti-poaching system is now taking shape and getting results. In the first five months of 2023, 281 tortoises were seized and the poachers caught and jailed. One thing is becoming clear based on the number of informants volunteering to assist the anti-poaching campaign: tortoise poachers have few friends, and there is a willingness to report their activities.

Sometimes just providing the opportunity is all it takes to inspire people to do the right thing. Such is the case with a young man named Salakasoa, a name that now stands out

in the Beloha district. He became a Village Volunteer in March 2023, having been trained with the necessary skills to identify and combat tortoise trafficking. This indicates a profound shift in the community’s perception of authority and justice, which has often been reticent or fearful of public administrations, especially the gendarmes and the courts.

In his short time “on the job,” Salakasoa has been involved in several joint operations, disrupting poachers and recovering tortoises. His tally is impressive, with over 305 tortoises saved and eight traffickers arrested through October 2023. Further, his testimony was crucial to the conviction of four poachers, who were given prison sentences and fines. Salakasoa’s commitment demonstrates the effectiveness of individual action, strengthened by training and institutional support, in the fight against trafficking of endangered species. His story is a testament to the power of community mobilization.

Our Confiscation to Reintroduction Strategy began to be realized in 2021 when 1,000 Radiated Tortoises were moved to a community-protected forest at Malaintsatroke in the Androy region and placed in a large soft-release enclosure for eight months. This was the first full-scale reintroduction of this species in Madagascar and represented a milestone in our effort to begin moving some of the 25,000 tortoises in our care back onto the landscape. This group was fully liberated in 2022 and a subset of 50 was intensively monitored via radio telemetry and GPS data loggers.

Two exceptional wildlife biologists, Lance Paden and Brett Bartek, took charge of the reintroduction process and designed a program that would not only generate finescale movement and home range data, but would also train and empower local Alliance staff and community members to track and monitor tortoises post-release. Building this level of capacity in-country is important to the future of this program and we are finding our Malagasy counterparts to be motivated and quickly become skilled at tracking tortoises in the field.

The reintroduction program took a major stride in 2023, which saw another 2,000 Radiated Tortoises return to the wild. In February, 1,000 tortoises were moved from the Tortoise Conservation Center (TCC) to the community of Ambatosoratse and placed in a 20-acre (8-hectare) soft-release enclosure for acclimation. In July, Brett Bartek attached VHF transmitters and GPS loggers to 20 tortoises for monitoring, and in October, the fences were removed and the tortoises were allowed to self-liberate into the surrounding habitat. At Malaintsatroke, a second group of 1,000 tortoises was received from the TCC and evenly divided amongst two soft-release enclosures. This strategy was designed to test

the impact of a three-versus-six-month penning period on site fidelity, or their tendency to remain in the vicinity of the pre-release enclosure. Data from the first 1,000 tortoises released in 2021 demonstrates that a six- to eight-month penning period is sufficient to encourage strong site fidelity; can that period be reduced by 50%? Additionally, and just as importantly, is the very low mortality rate observed in the 80 tortoises that have been tracked over the past two years.