7 minute read

Game Changer

Same game, different ballpark

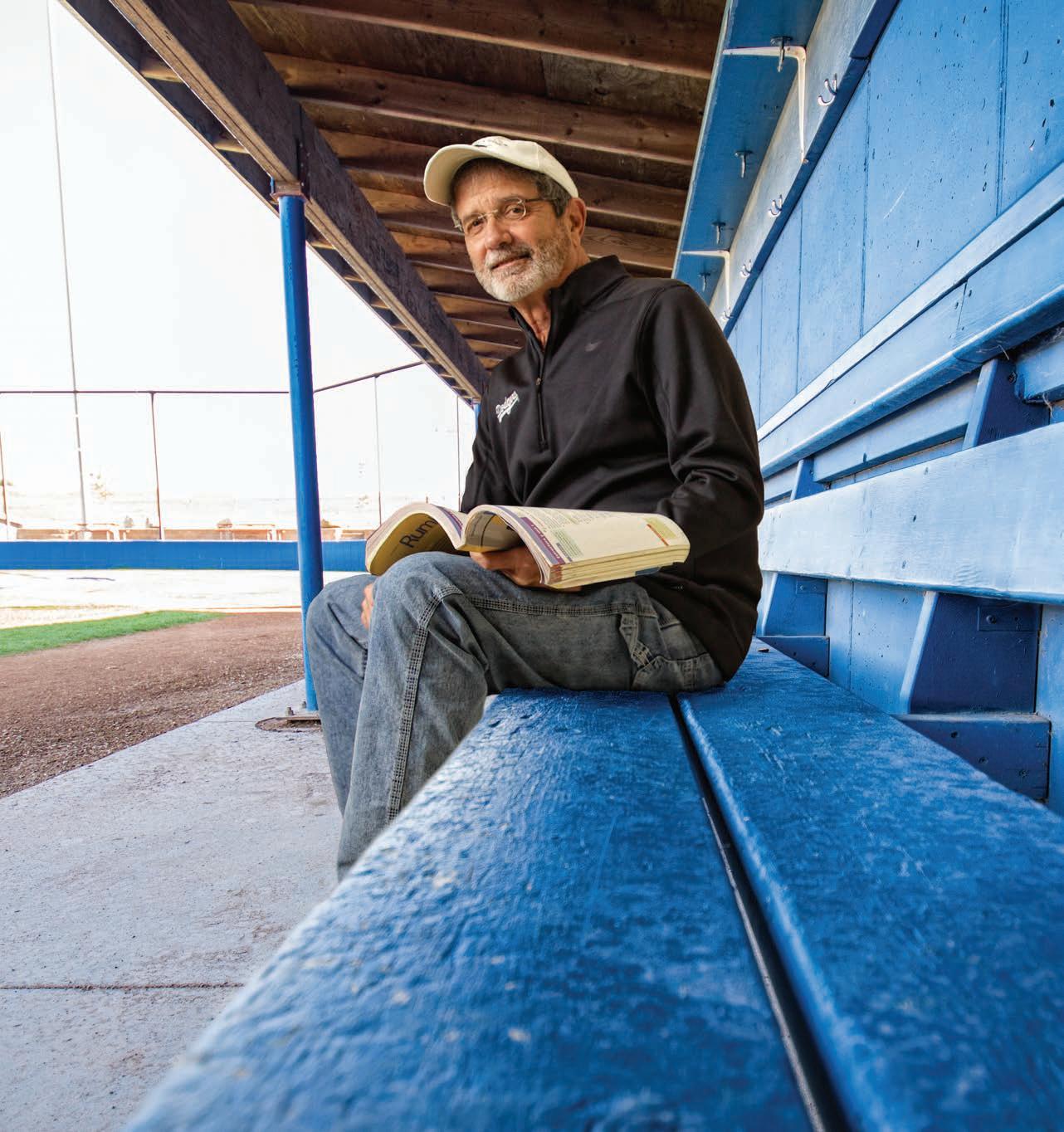

Tony Alonso doesn’t look “retired.” He’s tall, tanned, with good posture, an easy smile, and an affable manner. There’s a vitality to him, like maybe his best is still to come. He looks like he just walked off the golf course, or perhaps a ball field, which, depending on what day it is, might be the truth.

Advertisement

For Alonso, former TCC chief diversity officer, “retirement” has been more of a change of venue than a change in mission.

Within one month of his retirement from TCC, after 41 years of work in higher education, he hopped into the dugouts of the Tulsa Drillers and the OKC Dodgers.

“My job is to teach their international players from countries where baseball is ingrained in the culture – The Dominican Republic, Cuba, Venezuela, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Colombia, Panama, Japan, Korea – English, and teach the American players Spanish,” says Alonso.

He also teaches them the cultural components that go with teaching a language, such as beliefs and values, geography, climate, religion, economy, art, food, music, equity, diversity and inclusion.

“But language is number one as the organization wants their players to be able to communicate with their coaches, teammates and the media,” says Alonso.

If you’re into baseball at all, which Tony is, it’s a cool job, and one he sort of fell into.

The Los Angeles Dodgers contacted TCC in 2015, the same year Alonso retired, and described the position and who they were looking for. It wasn’t just someone who could teach their ballplayers English and Spanish – they also wanted someone with cultural sensitivity and experience. They hit a home run finding Alonso.

“I had been the chief diversity officer at TCC,” says Alonso. “That was the deciding factor for them. It’s a class act organization. In 1947, they broke the color barrier. To know that I’m working for them, that the climate of inclusion has continued all these years, it’s pretty special.”

Alonso gets all the behind-the-scenes perks you could imagine. He sits in the dugouts with players during some games, translating on the fly and helping them communicate. He holds language classes before games, often in the luxury suites at the ballparks. He’s even attended Dodgers spring training.

“I like the fact that I get to work with players who are highly motivated and dedicated to learning the language,” he says. “They see the value of learning English and learning Spanish. These guys are players, coaches, managers, administrators for the Drillers and OKC Dodgers, and they see the learning of the language as a bonding opportunity. It enhances their jobs.

“They’re just like the students at TCC. You give them the language and the vocabulary, and then you build up their confidence so they can speak the target language. That’s the payoff. I want them to be confident. They are very respectful and their dedication strikes an emotional chord.”

Alonso often takes his ballplayers to visit his classes at TCC (that’s right; he still adjuncts for the College).

“I like my students, the players, to talk to my Spanish classes, because I like students to hear how Spanish is spoken in different countries and regions. It’s the same language, it’s just intonated a little differently,” says Alonso.

The ball players don’t just visit his TCC classes, they go with Alonso into the community, and are especially inclined to visit programs, areas and schools where there’s poverty and underrepresentation. Last summer, many players visited a summer bridge program that included a large number of students living in poverty.

“I offer the players an opportunity to perform community outreach by speaking to elementary, middle, and high school students who live in poverty and attend schools with a high number of students on free and reduced lunch programs,” says Alonso. “The players gear up for this educational activity, volunteering to speak to students in our community, wearing their Tulsa Drillers jerseys. I don’t have to convince them to do it.”

Again, it’s been a change of venue, not of mission. Diversity, equity and inclusion has been his professional mission, and it began when he was a child in Cuba. Alonso’s family fled Cuba to the United States in 1961. They arrived with nothing and had to rebuild their lives. But his awareness of inequity began before they left home.

“I came from a family that did well in Cuba, but lost everything coming here, and we have a high level of

social conscience,” says Alonso. He remembers learning about inequity firsthand while in middle school. He attended a private school for white Cubans in Havana, and one day, a group of Afro-Cubans were bused to his school.

“They were wearing the same uniforms we were,” says Alonso. “They were there to attend mass, and then go back to their school. That day, I went home and asked my father, who was an attorney, ‘Where do they go to school? Why don’t they come here?’ He took me to a part of Havana I had never seen. It didn’t look anything like our school. My father’s answer was that the country kept people apart based on the color of their skin.

“It’s interesting that in 1989, I saw that at TCC. It was like déjà vu. But it was definitely for a different reason.”

Back in 1989, Alonso caught the eye of Dr. John Kontogianes, then Provost of TCC’s Northeast campus. While in graduate school, he worked as an adjunct, and Dr. Kontogianes took his advanced Spanish class.

“That particular semester, he was looking for a dean of student services at Northeast,” says Alonso. “In essence, that entire 16 weeks became an audition. He encouraged me to apply. He mentored a lot of people at TCC. He was a really special person.”

By the end of that semester, Alonso was offered, and accepted, the job. Almost immediately, he noticed a problem.

“There were very few students of color on the Northeast campus in the 1980s,” says Alonso. “That bothered me, especially because of that campus’s location and its immediate constituency. I got the impression someone had built a moat around the campus.”

So he and his team of directors, counselors and coordinators – and Alonso gives credit the TCC’s staff, administration, faculty, students, and student organizations – set about inviting underrepresented communities to the College. He made it a point to provide programming of substance, things that would prepare students and their parents to attend college. “When we began all this at TCC, we really had to change the culture. We started a really aggressive outreach program that sent the message that TCC is everyone’s College,” he says. “It went from 2,000 minority students to 10,000. We were establishing community partnerships with anyone who wanted to help us diversify the student body.”

Alonso gives credit to all his staff and the “people of TCC” for making it all happen.

“They worked very, very hard in creating a climate at the College that values diversity, equity and inclusion. They deserve a tremendous amount of credit. The work that was put in place, it was a total college-wide effort. Our goal was to diversify our student body, which we did.”

Word got out. Not just in the community, but across the country. The College began receiving national awards, and TCC staff were being called to speak as subject matter experts. The American Association of Community Colleges recognized the College with its st prestigious student services award – the “National Council on Student Development: Contribution to Knowledge and Exemplary Program Award” for the College’s work in the area of diversity and civic engagement. The press called, to the point where Alonso was unable to handle all the interviews himself.

“We were getting requests from institutions all over the country,” he says. “’Come and tell us how you did this.’ We received a lot of support from many entities and people as a result of getting the word out. It brought much honor to the College. When I think about the number of TCC students, the lives we have impacted over the past 50 years, helping them achieve their academic and career goals, moving onto better jobs that positively affect their families, giving them hope – it’s been an insuperable experience.”

Alonso may not be Dean of anything these days, but he’s an ambassador of the College’s mission, whether he’s standing in front of a classroom or translating in the bullpen.

“I’m actually retired, but not.”