10 minute read

Samer Mohdad By: Sabrina DeTurk

from Tribe 09

Samer Mohdad: Writing in Light Diversity, connection and contradiction in the modern Arab world

In the summer of 1985, Samer Mohdad followed his cousin Kamal into the heart of the ‘Mountain War’ being fought between the Christian Phalangists and the Druze Progressive Socialist Party (PSP) in the Chouf region of Lebanon. Kamal, Druze like Mohdad and a commander in the PSP, had agreed to allow his cousin to record the events of the summer’s campaign. Mohdad emerged from the experience with both a film titled Le but (‘The goal’) and a drive to continue his education as a filmmaker. He was 19 years old.

Advertisement

Mohdad would return to Lebanon during the holidays while completing his bachelor’s degree in photography at the École supérieure des arts Saint-Luc de Liège in Belgium and continued photographing the ongoing civil war in the country. After his graduation in 1988, he was employed by Agence Vu, a French photojournalism agency, for which he continued to shoot features on the Lebanese conflict. From all of this work came his first book, Les enfants de la guerre, Liban, 1985- 1992 (War Children, Lebanon, 1985-1992) which was published in France in 1993. Photos from the book were exhibited in Beirut and France and Mohdad began to acquire a reputation for capturing both the horror and the banality of persistent warfare, using a style evocative of street photography as much as of war photography.

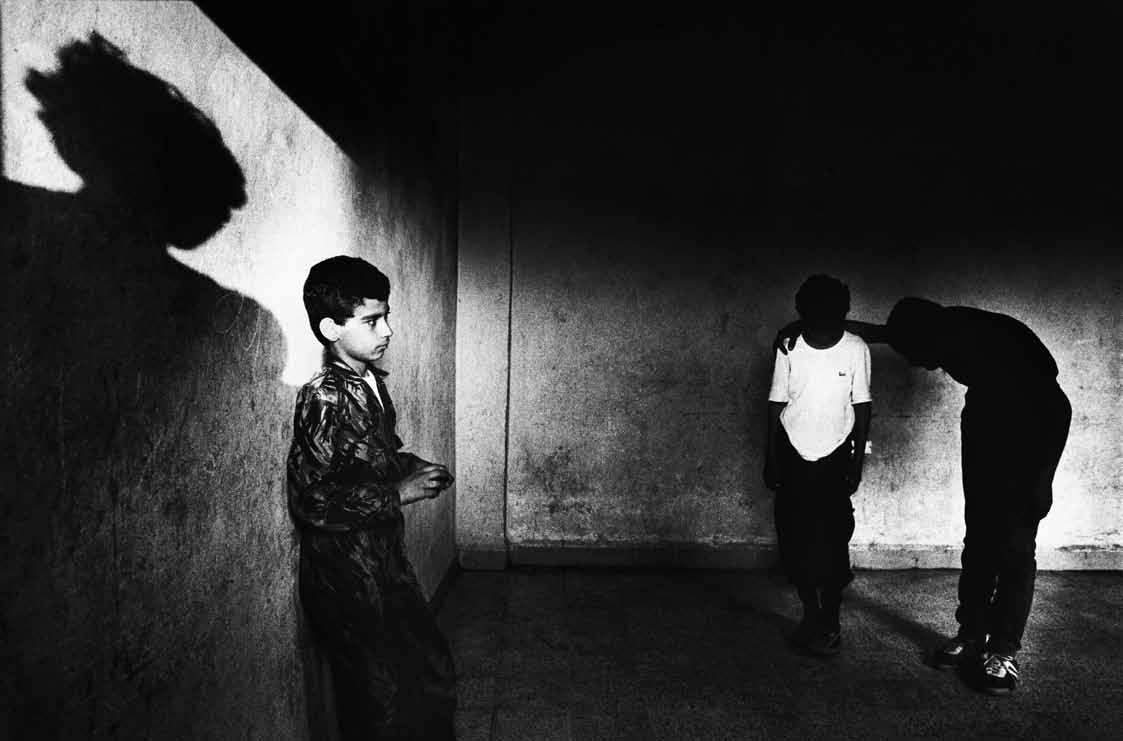

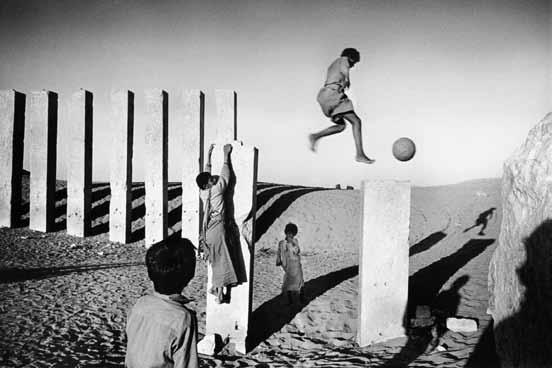

In War Children, Mohdad shows us the children of Southern Lebanon’s refugee camps in places like Ain el-Helweh, near Saida, where the Palestine Liberation Organization recruited child soldiers known as Lion Cubs. Mohdad photographed these young boys learning to shoot a military rifle but also learning traditional Palestinian dances, reflecting the profound disjunctions brought on by war. His photographic style is both straightforward and dramatic; children often face the camera directly, but the viewer is also drawn to backgrounds filled with shadow, in which secondary elements of the photo can tell a deeper story.

In 1996, Mohdad’s second book, Retour a Gaza (Return to Gaza), reflected the experiences of 415 men who were expelled from Gaza to South Lebanon in 1992 because of their connections to Hamas or to other Islamist organizations. Collaborating with reporter Andreas Dietrich, Mohdad visited the men in the Marj az-Zohour displacement camp in 1993 and then again in Gaza after their return in the summer of 1994. As with War Children, the photographs in Return to Gaza reflect Mohdad’s ability to capture both individual pathos and a larger sense of determination in the face of desperate circumstances. In a photo of Fadlallah Abu Taylakh taken at Marj az-Zohour, Mohdad portrays the exiled Palestinian as he changes clothes behind a makeshift screen stretched in front of the forbidding rocky landscape of South Lebanon. Only his face is visible, his eyes fixed in the so-called “thousand-yard stare” familiar to war photographers who have captured that vacant, resigned look on the faces of hundreds of soldiers over the years. A second photo of Abu Taylakh, taken in Gaza after his return from the camp, shows him lying on the floor, laughing as he hoists his young daughter into the air. The surroundings are scarcely less bleak than those of the previous photo, yet the

I wrote in light the stories of people from countries marked by centuries of clashes, and captured moments in time that make us face our realities as Arabs with deeper conviction.

joy on the face of this man as he plays with his child lights up the photo. Mohdad notes that many of the men he photographed for the project, including Abu Taylakh, later rose to positions of authority within Hamas and, thus, the work documents not only their particular experience but a broader sense of the growing importance of Hamas as a force to be reckoned with in Middle East politics. As Mohdad writes in the introduction to the book, “Besides telling a story of exile and return, one that touches on the destiny of the Palestinian people, Return to Gaza witnesses the beginnings of this rise to power.”

Preparing dinner at the Syrian Nationalist Party’s Lions cubs training camp in Mount Lebanon, 1989

This reflection on the power of his photography to document not just individual stories but a collective shift in consciousness and political commitment is germane to Mohdad’s next book, the first in a trilogy that would examine the variety of contemporary Arab life while attending to the historical vestiges present in current society. Mes Arabies (My Arabias) was published in 1999 and documents the photographer’s travels through 12 countries in the Middle East and North Africa. From the Friday markets of Algeria, where a dejected vendor sits in front of his secondhand goods laid out on a dirty street, to the National Day celebrations in Abu Dhabi, where two sheikhs recline on overstuffed sofas behind trays piled with delicacies, Mohdad continues his exploration of street photography as a means to capture the diversity of lived experience in contemporary Arab society. The dichotomy of Arab existence, expressed for Mohdad as a simultaneous experience of pride and defeat, is written in these images.

The second book in the trilogy, Assaoudia XXVIe s = XVe h (Saudi Arabia 21 st

century CE = 15 th century Hijri) was published in 2005 and documents Mohdad’s experiences in the kingdom, where he both traveled and lived in the early 2000s. The photographer first visited Saudi Arabia in 2000 to present his photographs from the My Arabias series in Riyadh for the celebrations of the city’s designation at Capital City of Arab Culture. He then returned to Riyadh in 2001 to set up the Centre for the Image at King Abdulaziz Library, a project which lasted until 2003. Mohdad’s photographs from Saudi capture the complexities and contradictions of life in the kingdom. He documents the lives of Bedouin women in the Empty Quarter whose remote way of life permits somewhat more freedoms than those afforded to women in the city. In a grainy photo from 2003, Mohdad captures a scene from a shopping mall in Jeddah. In the foreground, two uniformed guards are captured walking towards the camera. The image is cropped, showing only part of their bodies and focusing the viewer’s attention on their hands, which are touching. Their arms form a “v” that frames the figures of two abaya-clad women walking behind them. The gesture of touch, of easy physical intimacy, enacted by the men is contrasted with the erasure of physicality embodied by the veiled women behind them, reflecting the boundaries and differing modes of expression available to men and women in the society.

It was not until 2005, following the assassination of former prime minister Rafic Hariri, that Syrian forces fully withdrew from Lebanon, where they had maintained a strong presence in the mountain region since 1976. A reconciliation between the Druze and Christians in 1993, had paved the way for former residents to return to this region, but the ongoing Syrian presence and lack of basic services continued to discourage occupancy. Working with the EU and governmentsponsored AKFAR program, Mohdad developed the Mes Ententes (My Understandings) project to assess the return of displaced families to Mount Lebanon. His documentation of the project resulted in a short film and book of the same name, published in 2005.

With photographers Akram Zaatari and Fouad Elkoury, Mohdad established the Arab Image Foundation, headquartered in Beirut, in 1997. His 2013 book, Beyrouth Mutations (Beirut Mutations) recounts the reasons for this project.

In Mohdad’s words, “When I first exhibited my photography in the early 90s at the Musée de l’Elysée in Switzerland and the Musée de la Photographie in Charleroi, Belgium, there was no category for my work. The label ‘Arab photography’ simply did not exist. Up until then, famous images of the Arab world had been taken by outsiders, Westerners who traveled to the Middle East in search of exoticism and thrills. Therefore, I have decided to create the Arab Image Foundation to build up the Arab photography history starting from scratch, so my works and works of other Arab artists find an anchor point.” The ongoing work of the Foundation in both archiving photographic works and exposing them to new audiences is of critical importance to the visual arts in the Arab world.

In 2018, Mohdad published his only non-photographic book to date, Voyage en Pays Druze (Journey in Druze Country). In it, he recounts his childhood growing up as a member of this secretive and little-understood sect as well as recounting his experiences of the civil war that overshadowed his youth. Although the book does not contain photographs, Mohdad’s vivid language paints a picture of the sights and sounds of his youth and young adulthood, forming a companion to the visual documentation of his photography.

Mohdad is currently working on the third volume of his Arabs trilogy, which will be titled Le dernier Arabe (The Last Arab) and will include his most recent photographs from the Arab world.

From the series War Children (2014)

Gelatin silver print, 40 x 60 cm

Frontline between east and west Beirut seen from the

west, Zkak El Blat district downtown Beirut, Lebanon, 1989

From the series War Children (2014) Gelatin silver print, 40 x 60 cm

Children at the PLO Lions Cubs in the Ain el-Helweh refugee camp near Saida, south Lebanon, learn

Dabkeh, a traditional Palestinian dance, 1989

Next Page: From the series Return to Gaza (2014) Gelatin silver print, 60 x 90 cm

Part from the 415 expelled Palestinians arrive back at the camp after having marched to the border with

Israel to protest against their deportation, Marj az-Zouhor, south Lebanon, 1993

Gaza at Marj az-Zohour camp, south of Lebanon, 1993

From the series Return to Gaza (2014) Gelatin silver print, 40 x 60 cm. Abu Ahmed Jadallah

during exile at the Marj az-Zouhour camps in no man’s land, south Lebanon, 1993

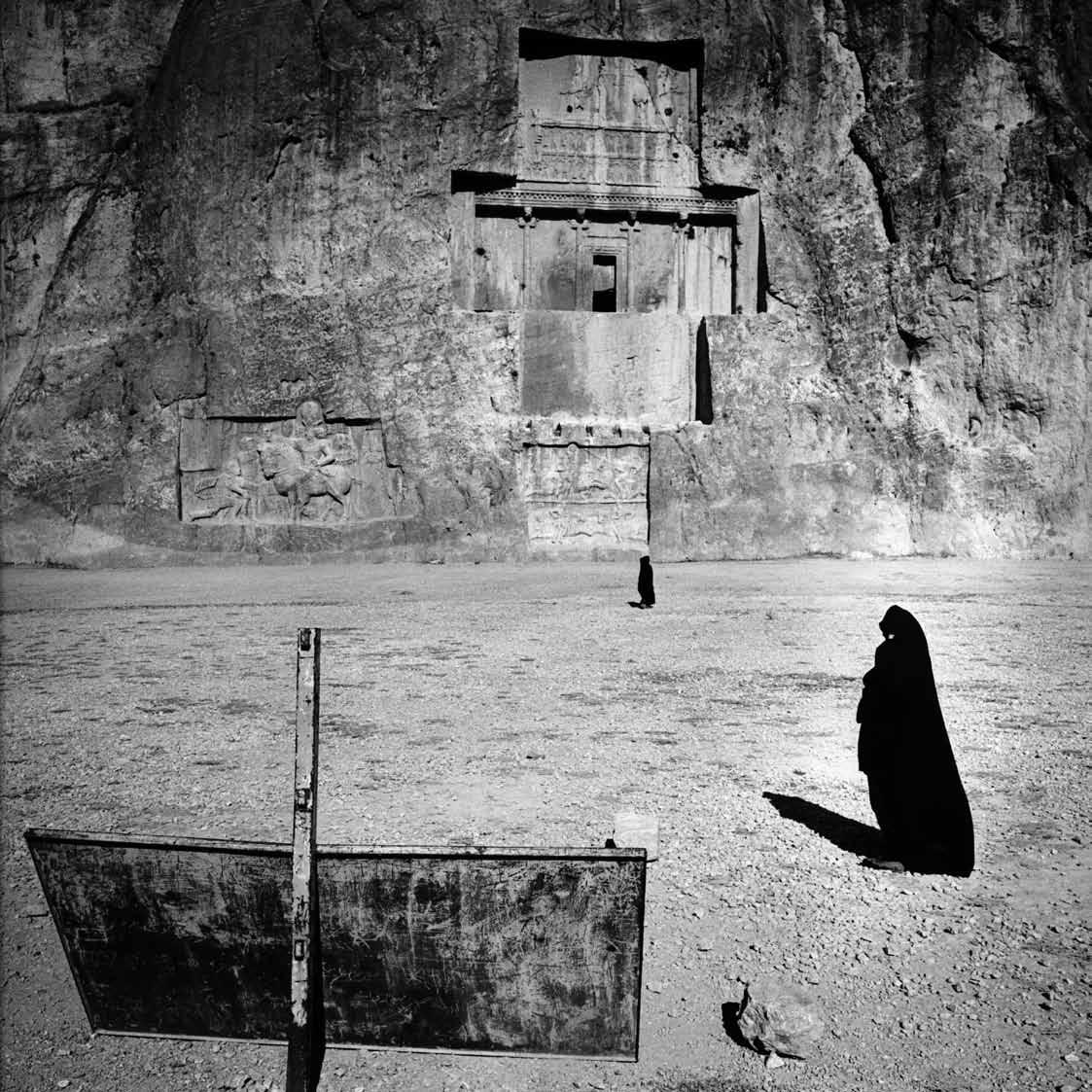

From the series Mes Arabies (2014) Gelatin silver print, 40 x 60 cm

Naqsh-e Rostam is an ancient necropolis located at 5 km of Persepolis, in Fars Province, Iran, 1995

Clockwise: From the series Mes Arabies (2014) Gelatin silver print, 40 x 60 cm

Indonesian students of Islamic theology at the Azhar mosque in Cairo, Egypt, 1994

Interior of an underground house in the old city of Ghadames, Libya, 1994

Remains of the Sun Temple of the Sabean kingdom, Marib, Yemen, 1994 Zawia Sidi Rahal, a mausoleum dedicated to the renowned Sufi man protector of travelers, Morocco, 1994

From the series Assaoudia (2014) Gelatin silver print, 80 x 120 cm.

Weekend picnic in the dunes in Mozahemia near Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2002.

Bedouin women after milking camels in the Empty Quarter, Sharoura, Saudi Arabia, 2003

From the series Assaoudia (2014) Gelatin silver print, 40 x 60 cm

Shopping mall in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2003

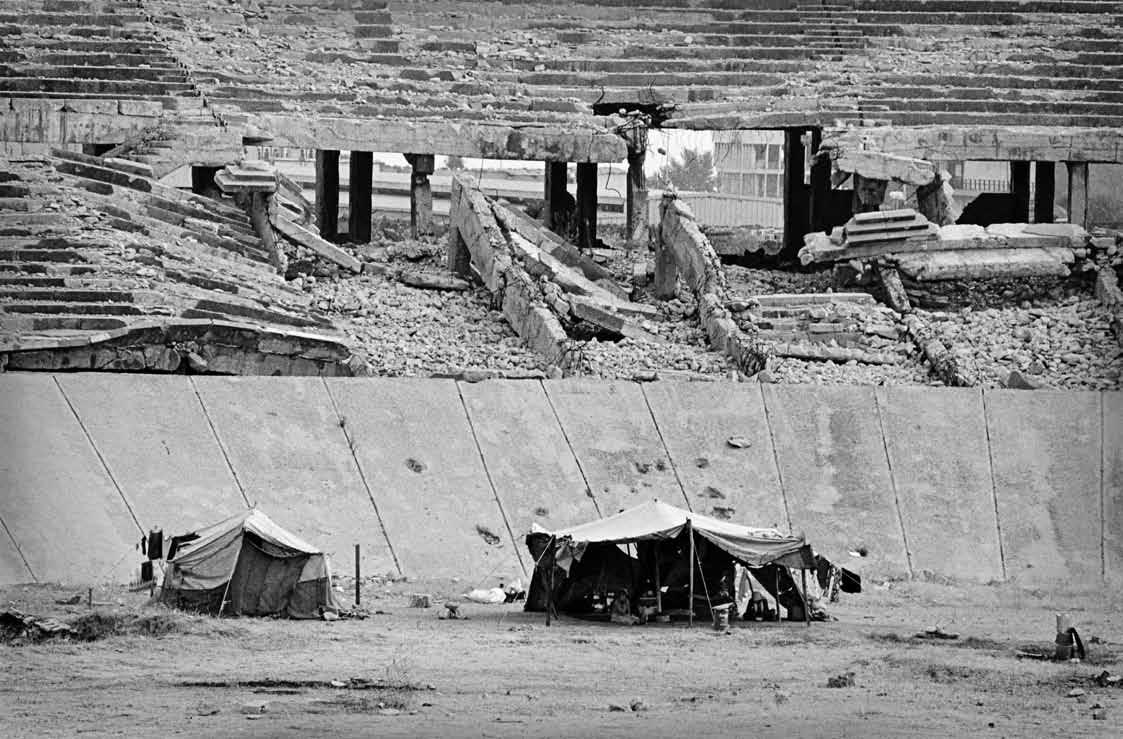

From the series Beirut Mutations (2014) Gelatin silver print, 60 x 90 cm

Camille Chamoun Sports City Stadium. It was destroyed during Israeli invasion in 1982. Beirut, Lebanon, 1985

Demonstration following Hariri’s assassination, Beirut, Lebanon, March 14, 2005.

From the series Beirut Mutations (2014) Gelatin silver print, 60 x 90 cm Dumping the front sea of Normandy with public garbage to create an artificial island, Beirut, Lebanon 1992.