4 minute read

Alfred Tarazi By: Ari Akkermans

from Tribe 09

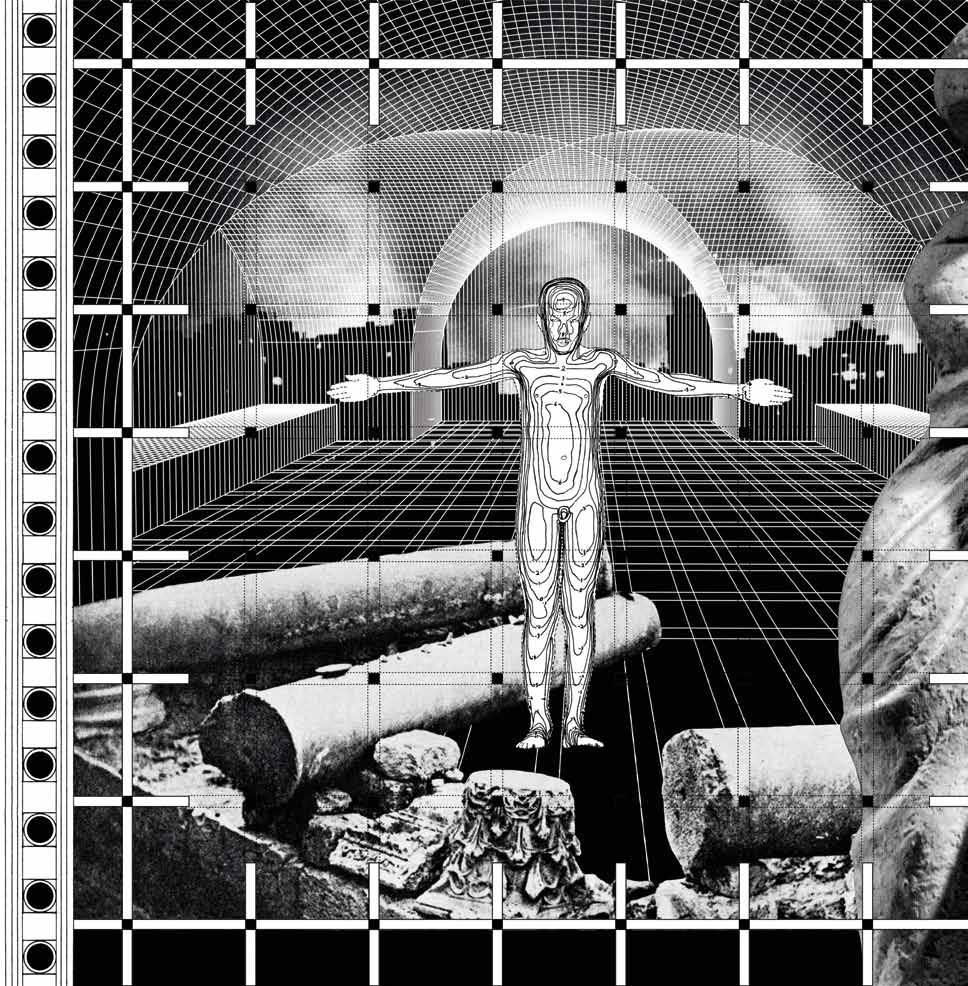

Alfred Tarazi: Dear Madness Collages from a vault of memories

How do we rearrange photographic knowledge in an event of historical cessation? We are not talking here about a mere interruption in the flow of the everyday, but a condition of dissolution. In his practice, Lebanese artist Alfred Tarazi has always been captivated (hostage, you may say) by the metaphysical transgressions of the Lebanese Civil War—it’s not just about violence, but the liquefaction of reality—and turns to representation with an almost cynical question: Is there a memory more reliable than a photograph? It is in fact here that we have the makings of madness. A convoluted, impossible, unbearable history reduced to a body of photography; overwhelming, partisan and interminable.

Advertisement

But instead of reversing the process or intervening the archive, Tarazi’s method is that of a conservator; how to restore the chronology? In his restoration work, photographs and archives reappear as para-text through juxtaposition, and emerge as footnotes to themselves—image, text and fiction in boundless composition. Out of this chaos, the absurd and the ambiguous merge into the roleplaying of historiography, leaving us at the mercy of singular, unexplained photographic acts. His signature collaged panoramas–an early ancestor of cinema—are a phantasmagoria of truncated images, unevenly distributed, wounded archive and dystopian mythology; references tear themselves off the flesh, melting into the whole.

And then, there’s “Dear Madness...”, where the observer is both subject and object of inquiry. In more recent years, Tarazi has distanced himself from the grand narrative of the war, towards an order of introspection, closer in time and personal in voice. Reconstructing the historical events that took place in Lebanon 2005-2006 between the Cedar Revolution and the end of the July War from a first person, the artist is not only putting together fragmentary recollections from the war, but rearranging his own vault of memories. Dear Madness is a fiction inside the archive, and the metaphor for a reckless, turbulent and unattainable love, Beirut herself: “This is your story, Madness, this is your city and this is your house.”

In the panorama Cara Matta (2019), on show in Art Dubai last spring, a kind of classical historical painting in scenes leads the viewer through a series of encounters between madness and himself, that intersect and overlap with key events in this period. The assassination of Rafic Hariri (among others), the establishment of the opposing camps that still divide the Lebanese political spectrum, March 8 and March 14, or the deadly war with Israel that for the umpteenth time, saw parts of Beirut destroyed. Is Madness the metaphor for Beirut, or vice versa?

In this epic of love, and well, madness, the fictional details are as important as the true events on account of their hagiographic nature. The assassination of Hariri on St. George Bay in 2005 merges with the legend of how St. George, the patron saint of Beirut, slayed the dragon in the medieval tale. Unlike the Greek epic that birthed St. George, in Cara Matta there’s no obvious resolution or hero; it is only because of its historical accuracy that mysterious streams of history are revealed, a reality that supersedes all fictions and annihilates itself. Using her European passport, Madness flees the country, and in the subsequent demolition of her house, another layer of story-telling is revealed.

Throughout the 24 scenes of this almost cinematic, historical painting, Tarazi invokes the unwritten architectural history of the city, not as a tool to enhance his narrative but rather as a general structure. It is through enclosure around physical sites and their history that the story becomes tangible: “The 8th of March [was] born on Riad El Soloh square, and the 14th of March on Martyrs Square. But those two squares have things in common. First they both contain statues, and second both statues were made by the same Italian sculptor, Renato Mazzacurati.” Photography, architecture, urbanism and war, all in equal measures part of the legacy of Modernity in the Arab world.

A modernity without restraints or limits, a simultaneous laboratory and museological showcase. For Tarazi, an artist always skeptical of images and politics, and often laconic in language, the photograph is no longer a medium but an early ruin. It is capable of immortalizing the unimportant, thus clogging the pores of history’s path, at the end of which there’s only non-reason without apocalypse: “This is her story, Madness, this is her city and this is her house. This is the ruin in which we made vows, this is the square in which we sang for freedom and this is the war we fought together. It has all vanished. It is all gone.”

horizontal, activated through a hand-powered crank