8 minute read

Where to Work. Jump Workplace Hurdles

from TWSM#7

Tanzania, Looking for Balance

As it happens for many emerging economies in the African continent, working in Tanzania is not something for the faint–hearted. Nevertheless things are changing. Today seems the right time to be there, high skilled Tanzanian professionals have the feeling that they can make a difference.

Advertisement

By ALEX DUVAL SMITH

There is no fuel in the generator so you start your day by bathing in a bucket. In the short time it takes to walk to your car, the tropical heat glues your newly-pressed shirt to your back. The traffic sits bumper-to-bumper in the dusty haze. Motorbikes swerve through the jam. Three-wheeler “Bajaj” taxis zoom past in the inside lane. You are going to be late-again. You turn on the car radio. It’s all in Kiswahili. And you think back with affection on your long, braindeadening European commuter days when a 15-minute delay was a source of profound irritation.

A country where you have to be, now! As in many emerging economies in Africa, working in Tanzania is not for the faint-hearted. But running your own business there “beats being an employee, any day,” says Subira Mchumo, aged 38, whose interior and architectural design firm is based in the commercial capital, Dar Es Salaam. “It’s a great place. It is the right time to be here. You feel you can make a difference,” says Josephine Makanza, 36, a director of an investment trust. Dave Coffey, a 38-year-old Irishman running a radio station, appreciates the journalistic rigor of his staff but misses European camaraderie, “There is no going for a pint with colleagues after a long week’s work.”

THE TRANSITION FROM FAMILYHOOD TO CAPITALISM Tanzania is unlike other East African countries. Ethnically and linguistically homogenous, its culture remains rooted in the vision of founding father Julius Nyerere who died in 1999. President Nyerere believed African traditional values were fundamentally socialist and he

01

02

Working in Tanzania in 2011

Sophie Chivet’s passion for architecture can be seen through all of her photographs. It doesn’t matter if she is working in black and white or color; she commits herself to a sharp light and a pure layout. Photo by Sophie Chivet, Courtesy of L' agence VU. 01 Traffic is a chaos. Cars, trucks, bicycles, mopeds, all help to build a horrible traffic jams in the cities. 02 The bureaucracy is still, unfortunately, a central problem in the country. Officials earn little. They should find money inside “the complications”. 03 The future mall still under contruction.

03

called the ethos “ujamaa” (familyhood). It translated into the creation of a nation of collective farmers, almost all of whom were thoroughly uncompetitive and were schooled to receive instruction. “We are still in transition. Tanzania is still finding its feet, politically and economically,” says Makanza of the Investment Climate Facility for Africa, a partnership between governments and the private and development sectors which aims to improve investment conditions in participating countries, among them Tanzania where it has its head office. Makanza, a Tanzanian national, grew up with traveling parents. She went to school in Swaziland and Kenya, and university in Wales and South Africa. “When I came back to Tanzania in 1998 people were only just beginning to embrace capitalism. In the workplace I was an oddity - a young lawyer and a woman to boot. People were used to women being teachers and nurses. If you look back at that recent past, you realize we have come a long way in a short time.”

TANZANIAN COMPLICATIONS

Mchumo also witnessed a few elder gentlemen falling off their chairs when she returned to Tanzania intent on opening her own architecture and design firm. Eleven years later, this diplomat’s daughter - who was schooled in Swaziland, Japan, Britain and Switzerland before going to university in Scotland - feels great frustration at the web of administrative tripwires hampering dynamic entrepreneurship. “It is very challenging starting your own business,” she says. ‘’The authorities are not straightforward with what is required of you. There are very few guidelines. It is as if everyone sits back to see where you will go wrong or where you will get frustrated so that they can make a buck in between.” Coffey, who is head of Radio France Internationale’s Kiswahili service, based in Dar Es Salaam, has had extensive

Ruanda Burundi

Uganda Congo

Kenya

Tanzania

Zambia Malawi Mozambique

contacts with tardy administrators in the 18 months since he set up the broadcaster in Tanzania. “What is frustrating is that it is not blatant corruption where people state their price. As a mzungu (white person) you feel as though there is constant suspicion of your motives. The civil servants seem to find ways - through the paperchain - of slowing things down so they can sting you. It atrophies everything. “I have encountered the same attitude both in dealing with visas for myself and my family, visas for non-Tanzanian staff, or trying to get a shipping container full of studio equipment into the country,” he says.

ONE OF THE GOALS IS:

BUILD PROFESSIONAL SKILLS

Staff working under Coffey and Makanza are drawn from all over Africa and even the world. Mchumo has seven staff, all Tanzanian. “The biggest challenge,” says the architect-designer, “is finding employees who are go-getters and who think of solutions instead of dwelling on problems.” She also struggles to find people who will deliver work which reaches the standards she expects. “The architecture and building sectors are thriving but quality suppliers and products are a big challenge. Most suppliers stock cheap and fast-moving Chinese products.” Coffey, who has 18 staff, feels estranged by what he calls Tanzania’s ‘’shikamoo’’ culture. “Shikamoo is a greeting that is usually reserved for elders but I get it because I am a mzungu. If I hold an office brainstorming session, there will be only limited feedback. The Congolese, Kenyan or Burundian reporters will speak out in a public forum but the Tanzanians will go away and compile a joint email to me. I am sure this collectivist approach is a hangover from the Nyerere period.” After her return to Tanzania in 1998, Makanza worked at KPMG before being called to the bar, taking a year out to study, then joining mobile phone operator Vodacom for three years before moving to her present job in 2009. “I have seen mindsets change. People are getting more confident in the private sector. They ask questions. They work late and they even take tasks home now that we have decided to turn the office generator off at 6pm to save money. I just wish our salaries could better reflect staff commitment,” she says.

RAISE WAGES, OR AT LEAST ALIGN

Tanzanian inflation has hit 20% in the past year. The monthly minimum wage – what a restaurant waiter might receive before tips – is 80,000 Shillings (about 45 Euro). A social worker is paid 470,000 shillings (225 Euro). Middle-ranking private sector salaries are four times those of civil servants, which partly explains why the palms of officials need greasing. Market food prices are much lower than in Europe but imported consumer goods cost considerably more. Dar Es Salaam’s power supply cannot cope with the demands of businesses and the expanding middle class. This year, there have been fuel shortages.

WE NEED ENERGY

Running her own business, Mchumo feels the overheads burden full-on. “Electricity blackouts pose a huge problem. We work on computers and use photocopiers and printers. The current electricity shortages and power rationing means having to use a generator and running it is costly.” To keep up with international design trends, Mchumo needs to surf the web in her spare time. She does so at a price. “We have high communications bills and internet is still very slow so we spend a lot of time waiting to transmit documents back and forth. Mobile phone costs are high, too, and unavoidable because we spend a lot of time on project sites.”

In the wake of the global financial crisis, Tanzania and many other African countries are enjoying the return of a generation of highly-skilled professionals, like Mchumo and Makanza. They, being Tanzanians, enjoy taking part in a revolution that will change their country forever. It is an inspiration well worth enduring sweaty traffic jams for. For European Coffey it is a different story. The frustrations are enormous. Yet he values what he calls “the incredible, mind-boggling challenge” that working in Tanzania represents. •

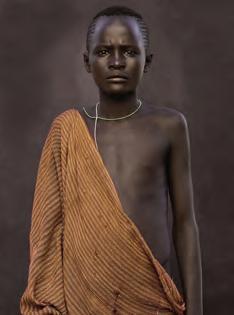

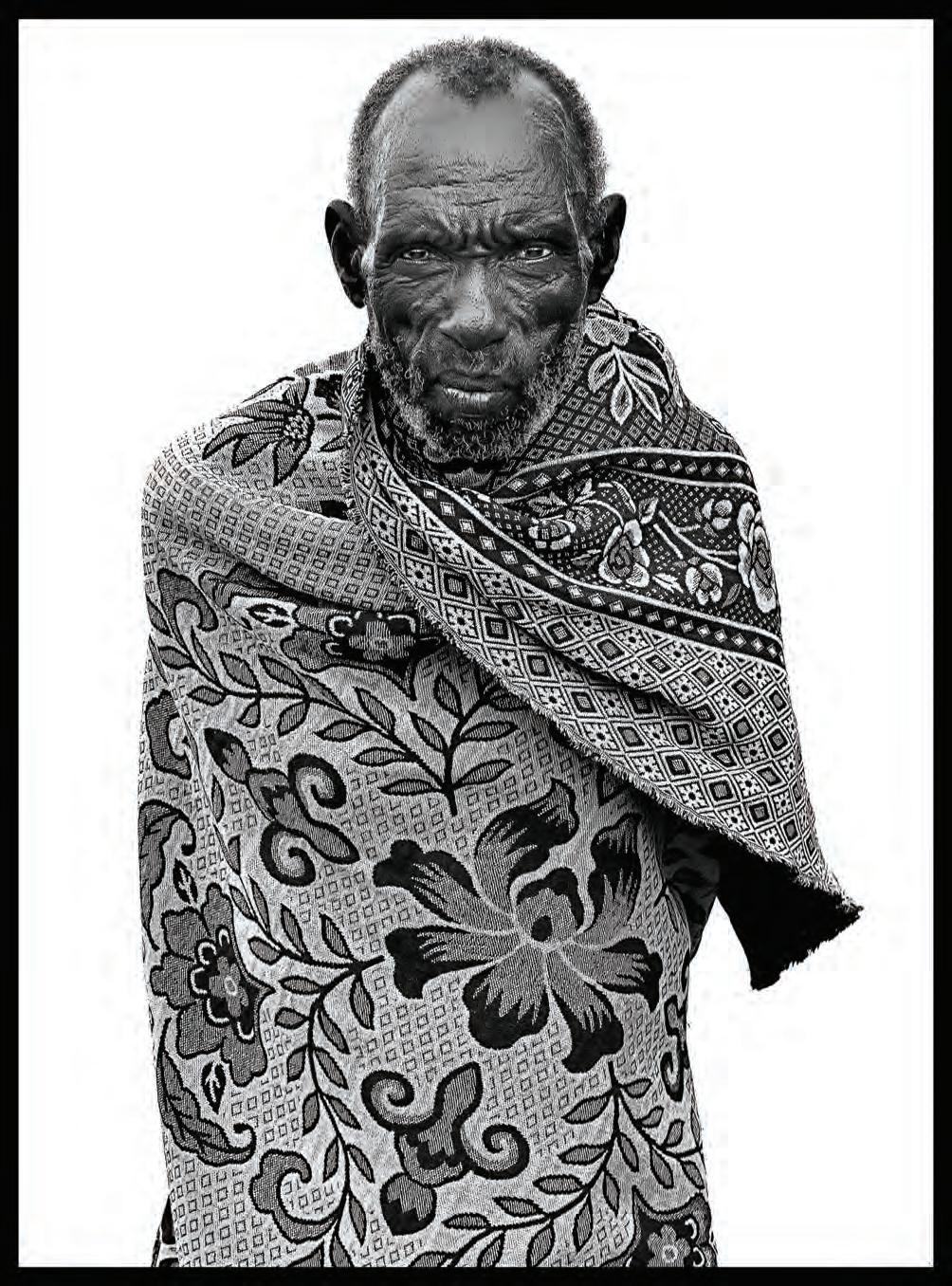

Mario Marino Faces of Africa

An Australian born photographer, Mario Marino has spent the last few months in Africa taking what he calls “photographic psychograms” of its inhabitants. Each gorgeously spare portrait represents a different microculture of the region, which Marino chose for its incredible density of distinct ethnic minorities. 01, 02, 03, 04.

The eyes of the Karo boy like a defiant look from the undergrowth, as if man had just stepped out of the great order of nature still hesitating to make the final step, which will leave him definitely on his own. In the spring of 2011 the now Germany based photographer Mario Marino headed to this African origin of mankind with the firm intention to record everything before long, it will be irrevocably lost. He finds villages and pastures recalling the desolate reservations of Native Americans in North America. The pressure of global civilization can be felt everywhere. The voyeuristic glare of the first tourists and in some areas an epidemic alcoholism gradually eclipse cultural identities.

01 02 03