In search for warmth – 18 –

From fire with peace – 6 –

Death of a performance actor – 9 –

Spicy food – 12 –

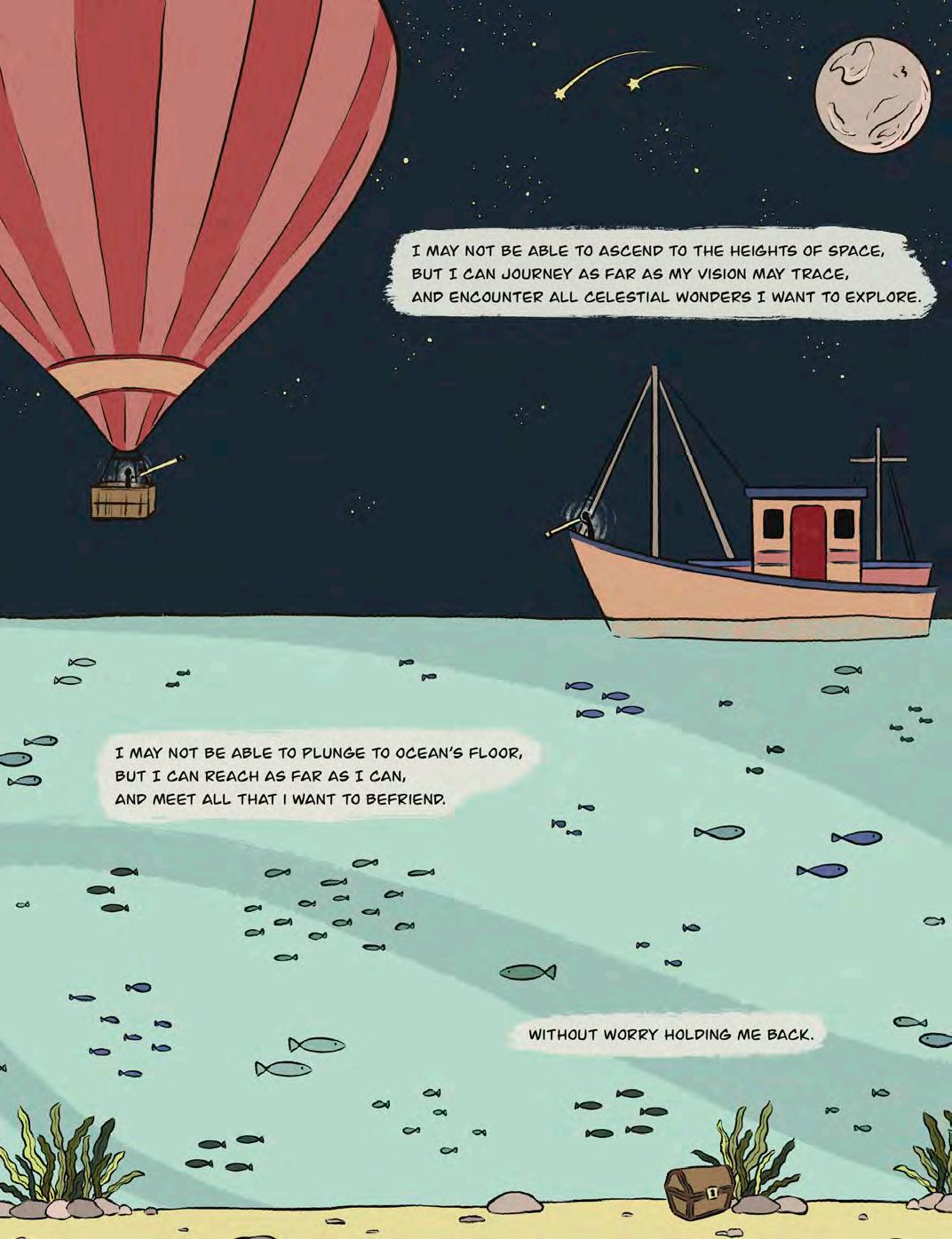

On intellectual freedom – 15 –

Trials by fire – 20 –Surrealism – 25 –

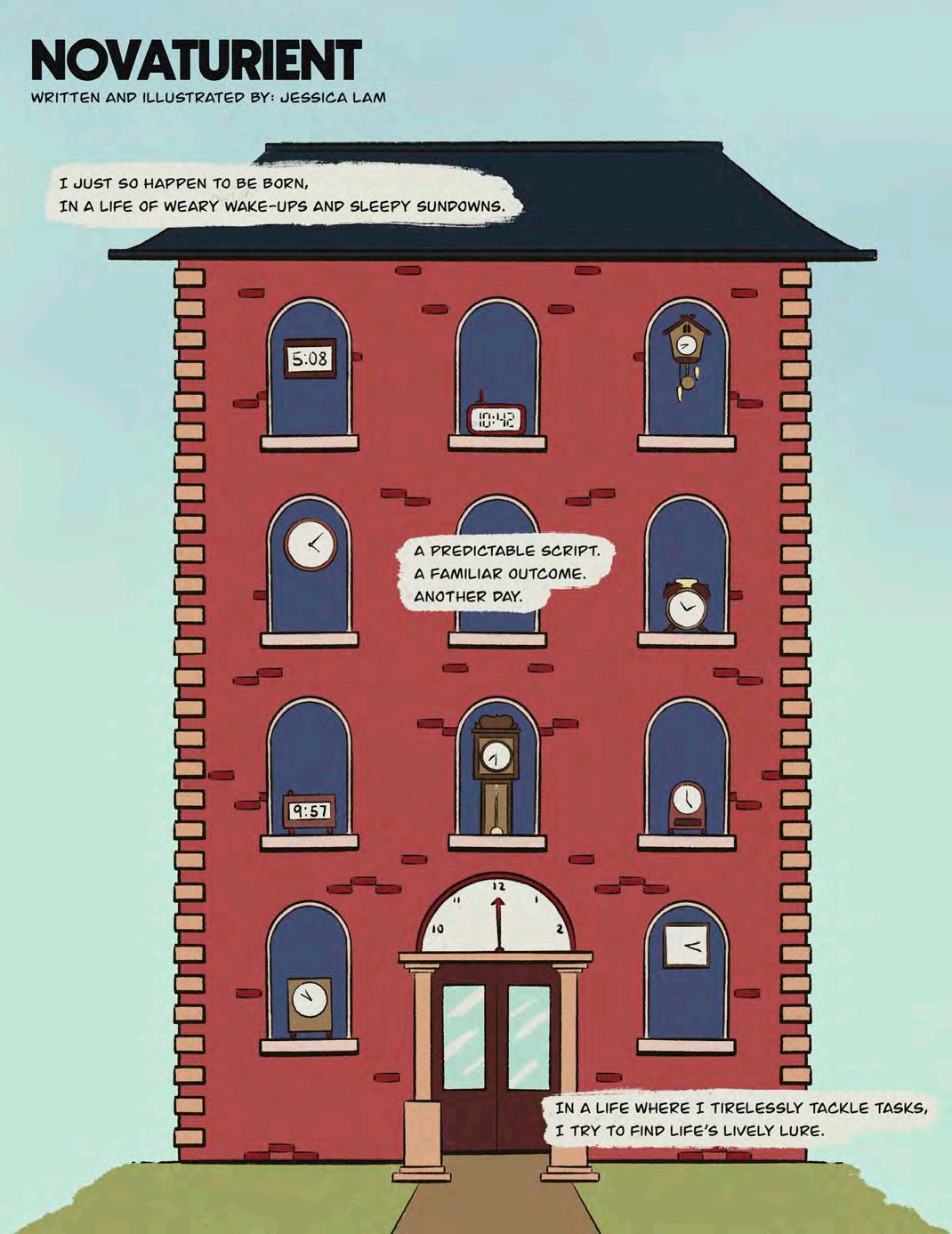

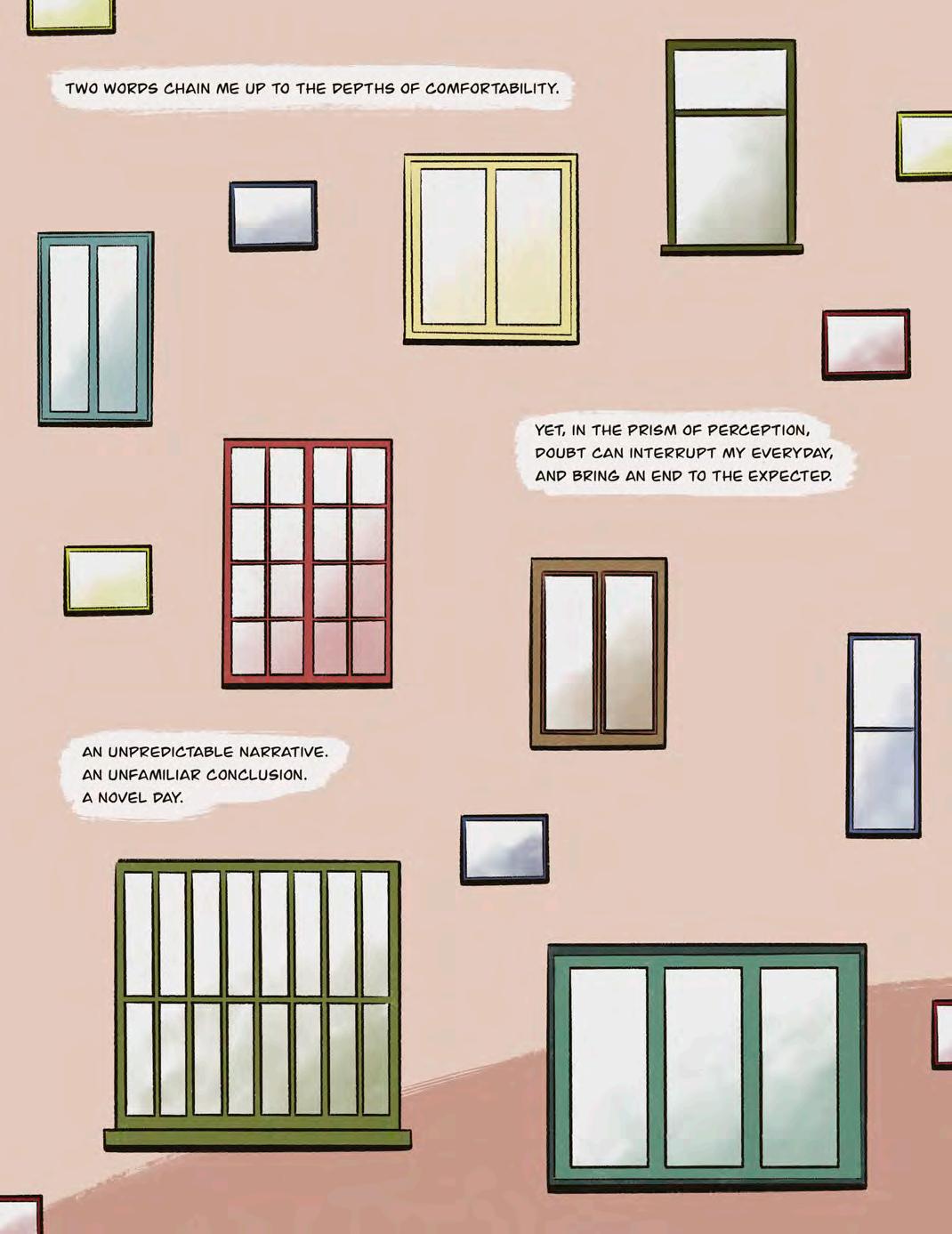

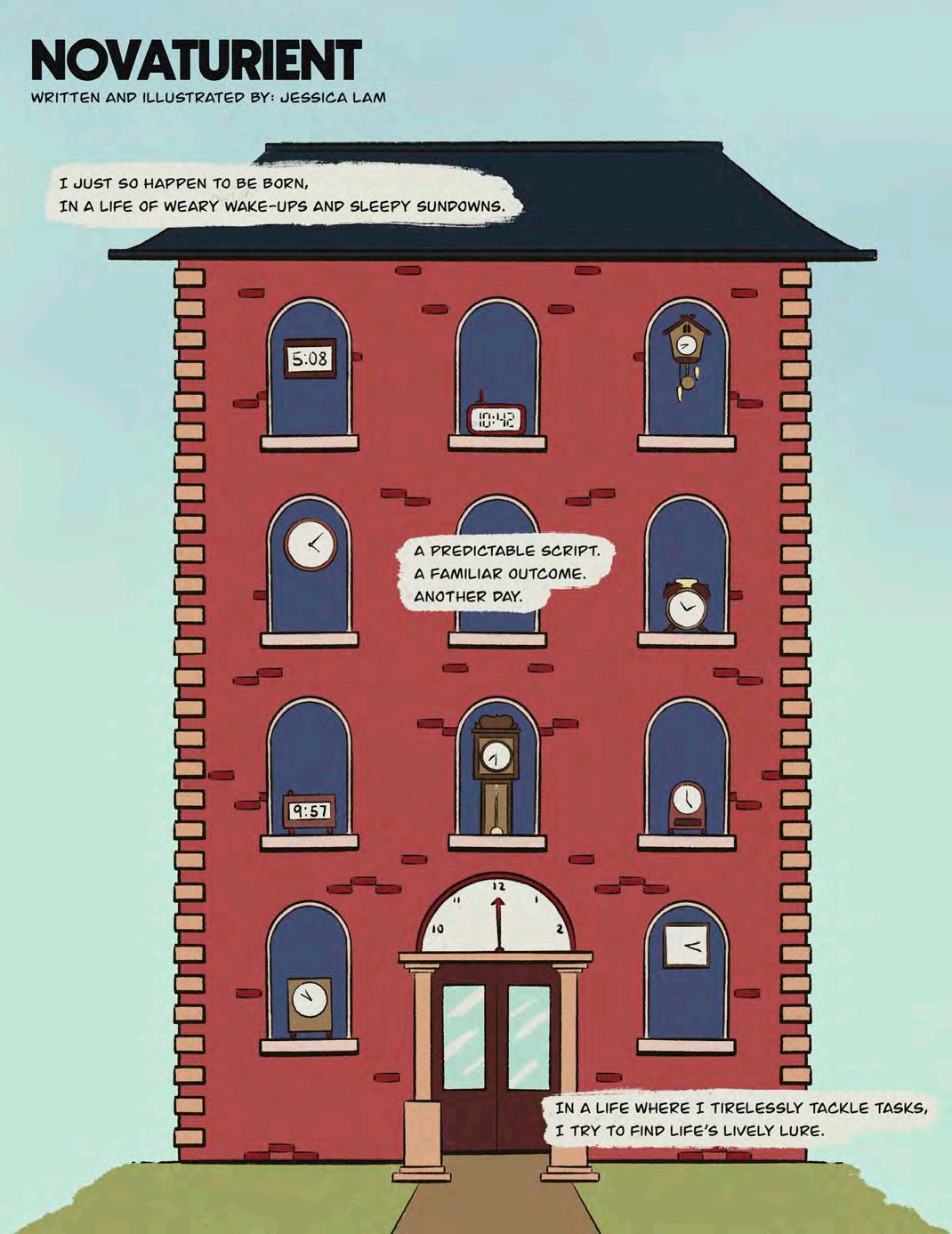

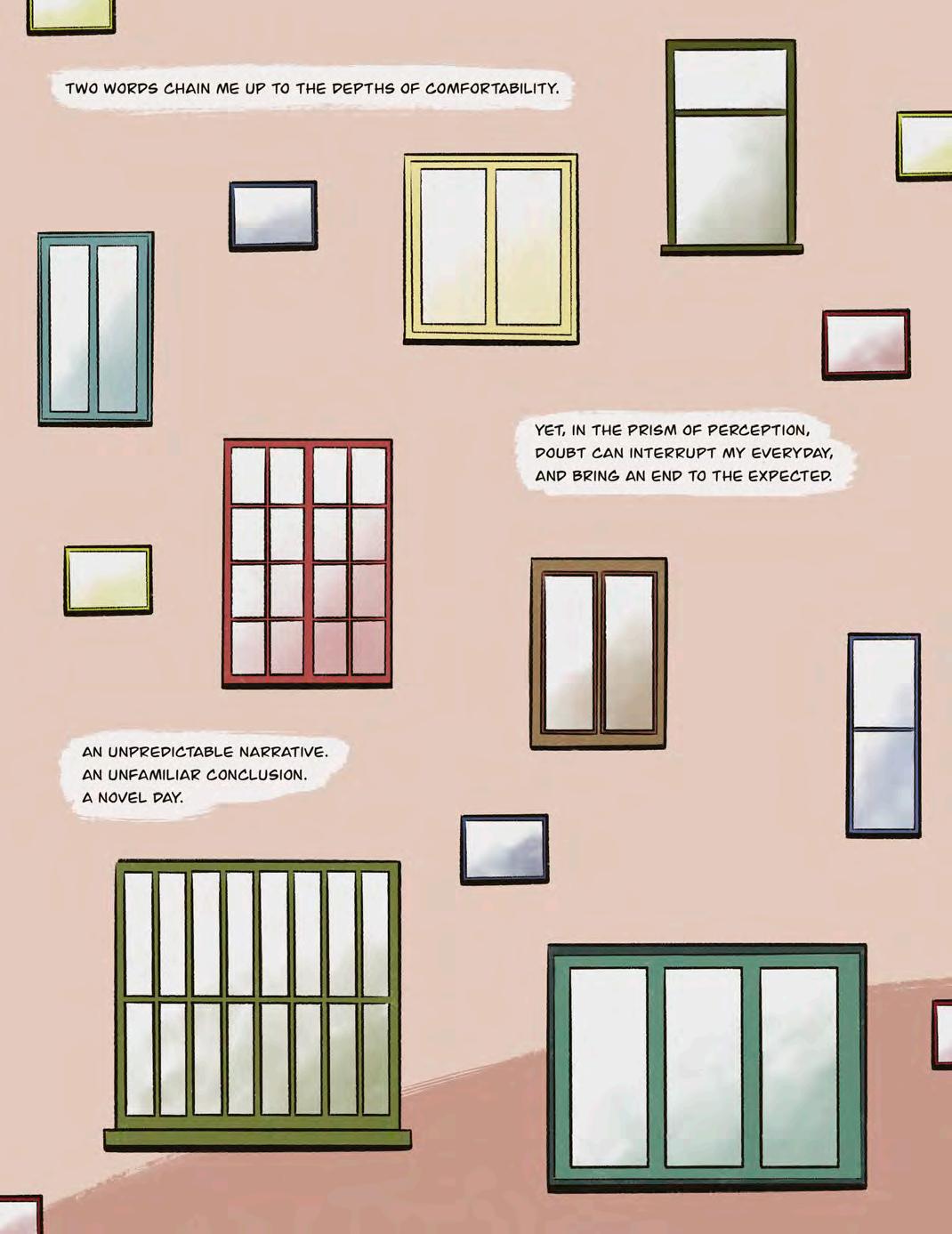

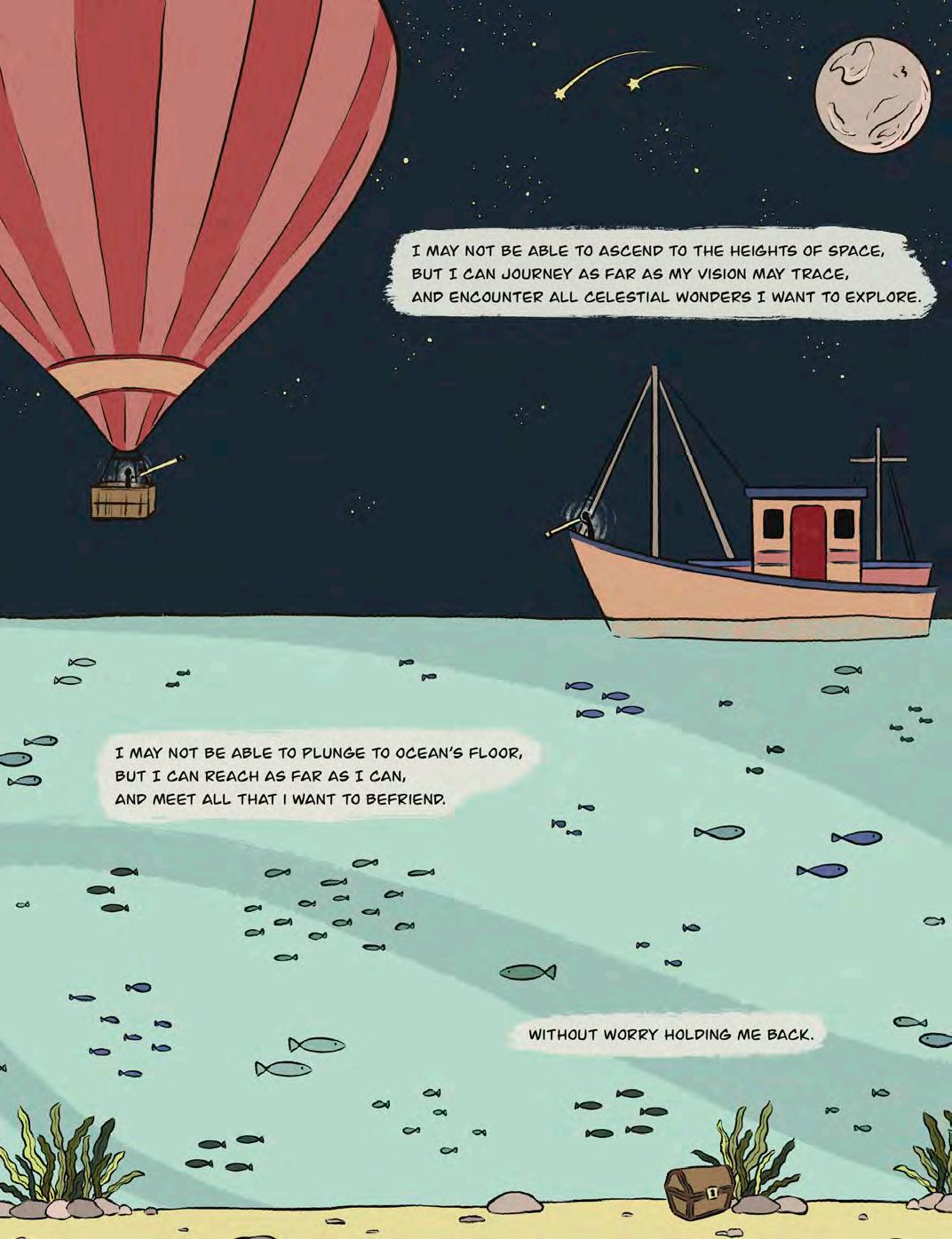

The politics of female rage – 26 –Novaturient – 28 –

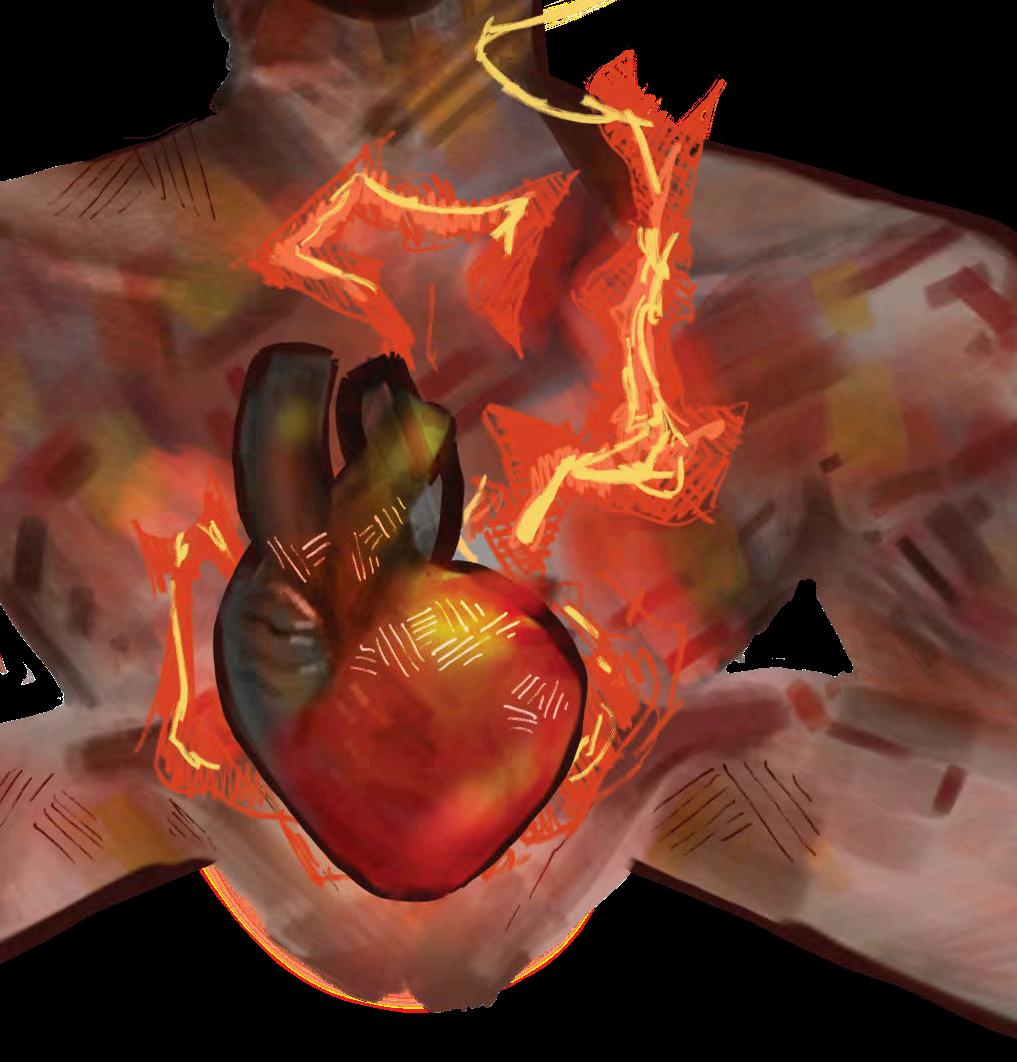

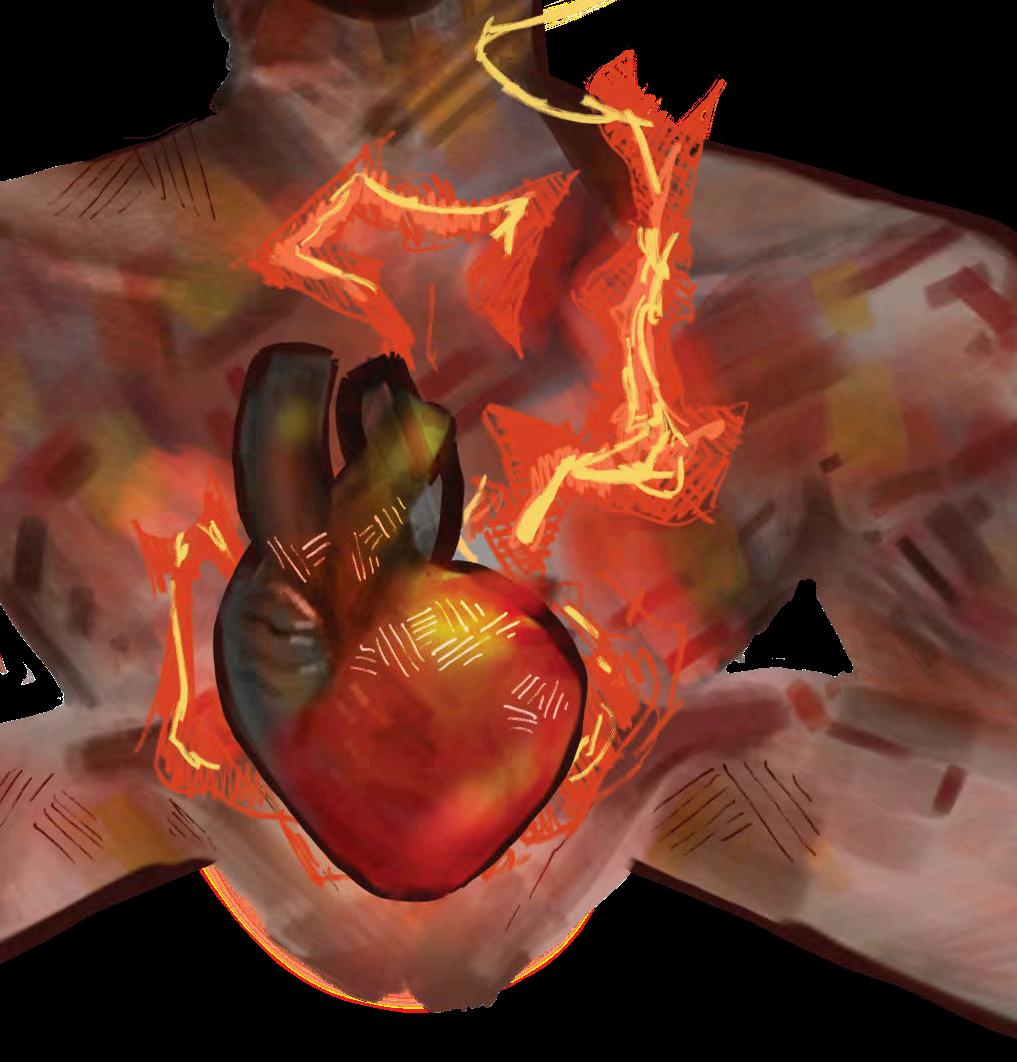

When love burns too bright – 34 –

Running for (your) life – 36 –

From ashes to renewal – 42 –

The hope of Prometheus – 44 –

20s bucket list – 46 –

Time to start again, perhaps – 48 –Spring, winter – 51 –

Tolstoy’s burnout – 52 –

Birthday present – 54 –

Kindling & rekindling trust – 55 –Chasing embers – 58 –

Live, laugh, love, lithium – 60 –

4 The Varsity Magazine Letters from the editors

The theme for this magazine, Flame, was not borne of rage. It was not borne of emotions so turbulent that they could induce seasickness. Rather, Flame came from me feeling completely numb.

Storytelling is my first love. I still remember the rush I felt when I weaved a story out of the fibres of external research and interview transcripts. Realizing that I wanted to write longform journalism as a career was one of the first and probably only true epiphanies I’ll ever have. However, I’m used to giving things my all, and throwing my entire being into everything I do. So much so that afer four years of doing that, I’ve forgotten about the consequences that come with being consumed by things you love.

The fallout of being consumed was being lef with nothing. I found myself too tired to do even the most mundane tasks, and every emotion that arose within me felt muted because I was too tired to feel anything. The most glaring example of this is probably the constant state of disarray that my bedroom has been in this school year.

To me, the theme of this magazine is about love — more specifically, it’s about the love I have for telling stories. For a terrifying few

weeks in January, I was so tired that I lost the ability to string words together into sentences. And when I found myself unable to write, I found myself on a frantic search for my lost love, for the hope that writing stories brings. For me, the process of making this magazine documented that search.

Despite it being the primary source of my exhaustion, storytelling is still what keeps me going. I guess I’m just so used to giving things my all that I forget that projects end but I remain. That even though my digital footprint on a newspaper’s website lasts forever, I have to take care of my finite, vulnerable self first.

I know that, even though my last project for The Varsity was borne of burnout and exhaustion, the sof glow of that love for stories will keep me standing. Thank you for picking up this magazine, and I hope that the stories you read here will remind you of the volatility of the things we love — the life-giving joy it ofen brings and the destruction it can leave in its wake.

— Alice Boyle, Magazine Editor-in-Chief

I kind of fell into involvement at The Varsity by happenstance.

My first year of university was full of lockdowns and missed opportunities. Taking photos for The Varsity was one of the few things I could do, and so I did it. At the end of the year, I found myself frantically writing a speech that I didn’t know I had to prepare minutes before I had to speak so I could become next year’s photo editor. I spent the first many months of that term diligently completing all of my work behind my computer screen, terrified of everyone around me, who all seemed so much more capable.

The following March, I experienced my first magazine production. Many late nights at our ofice and cold, windy days photographing things across downtown Toronto made for a stressful but endlessly fun several weeks.

I might have fallen into my first job at The Varsity by happenstance, but I stuck

around until now because I fell in love with the process of making a magazine that winter. Since then, I’ve tried many things, but nothing has felt as exhausting and endlessly joyful as making magazines.

This is an awful lot of self-reflection for a letter from the editor, but it’s because I’ve realized this is the last project I’ll ever put out at The Varsity. This is the last magazine I’ll spearhead for a while, if not ever, and well, I guess I’m feeling just a little bit sad about that.

It’s very fitting this magazine is called Flame, given it was through the last four magazines that I found something I felt passionate enough about to work tirelessly to complete. To me, Flame means finding the things you love so much that you are willing to be consumed by them. Through the pages that follow I hope you can get a taste for the joy that went into creating them.

— Caroline Bellamy, Creative Director

Winter 2024 5 Flame

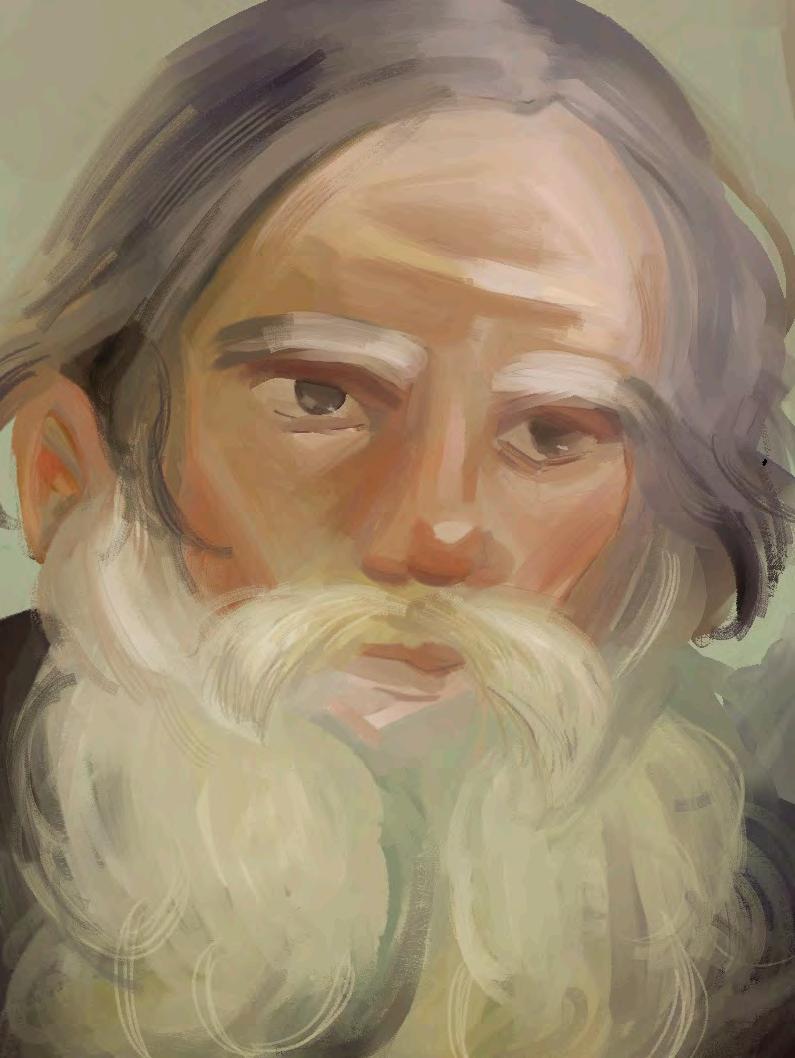

Doukhobor organizers of the Burning of Arms in Kars province, 1895. (l-r) Ivan I. Planidin, Peter I. Dorofeyev, Grigoriy V. Verigin, Pavel V. Planidin, Semyon E. Chernov. Koozma Tarasof Collection.

The Doukhobor burning of arms

Writer: Justus Van Ewyk

Content warning: This article discusses violence, torture, and sexual violence toward women.

The events described in the article below are an iconic part of the author’s Doukhobor heritage, and various elements of the story are part of the oral and published history of the Doukhobors. For some of the specific details in the story, the author relied on the comprehensive article by Doukhobor historian D.E. (Jim) Popof, publicized as a four-part serialization in the Doukhobor periodical, ISKRA, beginning with Issue No. 2089, April 1, 2015.

Between 1899 and 1905, many Doukhobors arrived in Canada in a mass immigration, exiled from their homes across Transcaucasia, in the south of the Caucasus area. In the wake of their departure from the Russian Tsarists’ control lay the ashes of one of history’s greatest stands against violence, militarism, and war in three smouldering piles of rejected armaments. In the face of abuse, torture, and death, the Doukhobors refused to act against their beliefs and embodied values of truth, peace, and pacifism.

I am one of many Doukhobor descendants of those who participated in the Burning of Arms and survived to make a new home in Canada. Over the last several decades, the history of the Doukhobor has been largely forgotten by the general public, and those under 30 outside of the main Doukhobor settlements are likely

to have never heard the word ‘Doukhobor.’ The history of the Doukhobor is complex, tragic, and ultimately inspiring — and, in today’s increasingly aggressive global political environment, has never been more relevant.

While the treatment of the Doukhobor following their immigration from the Caucasus likewise deserves to be remembered and spoken of by both the Canadian people and the Canadian government, it is their life under the rule of Russia’s Tzars on which this article focuses.

As midnight struck on June 29, 1895, the Doukhobors would light the skies of three Transcaucasian regions with mass burnings of weapons that declared their refusal to comply with the Tsar’s military conscription, which opposed the Doukhobor faith.

This important moment marked the fulfillment of Doukhobor leader Lukeriya Vasilyevna “Lushechka” Kalmikova’s prophecy, translated to English by Popof: “The time would come when, with the help of a strong leader, the Doukhobors would make a decisive break with violence and war.”

Twenty-five years afer Lushechka made this prophecy, Peter Vasilyevich “Petyushka Gospodniy” Verigin would inspire the renunciation of militarism and the Burning of Arms, freeing his followers from military servitude to the Tsarist empire.

Background

Under the rule of Russian Tsar Alexander I from 1801–1825, the Doukhobors — a Christian people of Russian origin known for pacifism — were

granted a large expanse of land in the region of Tavria province known as ‘Milky Waters’ on January 25, 1802. Along with this land grant came some protection from repression and extermination by the Orthodox Church and State, as well as an exemption from military conscription.

However, from 1841–1845, the Doukhobors were exiled from Tavria following accusations from the Church, state, and surrounding settlements for “trying to convert the surrounding population.” Refusing to return to the Orthodox Church and comply with military service laws, the Doukhobors were forced into exile in Transcaucasia, where a life of peace remained decades away.

In 1874, conscription was introduced to the Caucasus and enforced on the Doukhobors by the Caucasus Governor-General — the commander-in-chief of the Russian troops in the Caucasus during the Russo-Turkish war. To achieve Doukhobor compliance with conscription and participation in the RussianTurkish War, the Governor-General informed Lushechka that if the Russian military efort was unsuccessful, the Turkish army might well invade Russian territory — and that meant Doukhobor villages would be subjected to rape and pillage should they not assist the Russians in at least a non-combatant capacity.

Lushechka reluctantly agreed to the Doukhobors’ non-combatant participation — a compromise that weighed heavily on her shoulders. Thus, in 1882, wanting to avoid another necessary but shameful surrender of her principles, Lushechka began teaching Peter Vasilyevich Verigin the Doukhobor ways, hoping he would be the leader she had prophesied.

6 The Varsity Magazine From fre with peace

A new leadership

Following the passing of Lushechka on December 15, 1886, the majority of her 20,000 followers acknowledged the leadership of Peter Vasilyevich on January 26, 1887. The approximately 4,000 who did not were led by Ivan Baturin and Alyosha Zubkov, and headed by Michael Gubanov, Lushechka’s brother. Henceforth, these Doukhobors would be known as the Gubanovtsi or the ‘Small Party.’

The Gubanovtsi, as the ruling bureaucracy, were interested in preserving the status quo and induced the authorities to arrest Peter Vasilyevich at the very moment he was proclaimed the leader. Petyushka Gospodniy, at the age of 27, was subject to imprisonment and exile for over 15 years. Despite this, those who recognized Petyushka Gospodniy remained loyal, adhering to the messages he was able to send during his lengthy detainment.

On November 8, 1894, the annual commemoration of the Archangel Michael commenced. On this day, Petyushka Gospodniy’s followers were asked to adapt their daily practices in the name of their faith: at the counsel of Petyushka Gospodniy, most of his followers ceased consuming meat, alcohol, and tobacco, in addition to stopping the procreation of children in preparation for the challenges they foresaw.

Approximately 4,000 of Petyushka Gospodniy’s followers were not interested in making these changes and broke of under the leadership of Aleksey Fyodorovich Vorobyov to form the Vorobyovtsi or the ‘Middle Party.’ The 12,000 who remained loyal were known as the Verigintsi, or the ‘Verigin Party.’ It was the Verigintsi that would later take part in the Burning of Arms.

In autumn of 1894, Petyushka Gospodniy sent

his older brother, Vasiliy, and community elder, Vasiliy Gavrilovich Vereshchagin, to discreetly spread his instruction that on June 28, 1895, the Verigintsi were to gather all the weapons in their possession and destroy them by fire.

Petyushka Gospodniy also suggested that young Doukhobor men in active military service could announce their refusal to continue serving on Easter Day. Matvey Vasilyevich Lebedev was the first of many brave Doukhobor men to assert their refusal to bear arms and continue military participation; ten fellow Doukhobors in his company followed his lead, thus sparking the events that culminated in the Burning of Arms.

In the face of abuse, torture, and death, the Doukhobors refused to act against their beliefs and embodied the values of truth, peace, and pacifsm.

These first 11 men would not return to service, remaining dedicated to the principles of their faith and Petyushka Gospodniy’s leadership. For their refusal, the young Doukhobor men were arrested and subjected to solitary confinement and constant threats; beatings; physical and psychological torture; and mock executions in the Penal Battalion. Yet the men would not break, persevering through repeated floggings of minimum 30 strokes and up to a shocking 120 — with their fellow Doukhobors as a forced

audience of the torture. Afer flogging, the men were sequestered in isolation with only the company of insects, rats, and festering wounds.

Of the first 11 men, Mikhail Mikhailovich Sherbinin was the first to die for his beliefs. An estimated 300–400 Doukhobor men would follow the fate of the first 11 over the next three years, between 1895–1898, eventually being exiled to Siberia as religious sectarians. Dozens of pacifist Doukhobors, particularly young men, would lose their lives in their resolute stand against militarism.

The Burning of Arms

Meanwhile, June 28, 1895, finally came: at midnight and well into the hours of June 29, the Burning of Arms commenced simultaneously in the regions of Kars, Elizavetpol, and Kholodnoye. The Doukhobors were asserting their faith and beliefs in what I see as one of history’s most remarkable stands against violence and war.

In the Kars region, under the oversight of respected elder Ivan Ivanovich Oosachyov, Petyushka Gospodniy’s younger brother Grigoriy Vasilyevich, along with Ivan Ivanovich Planidin — my direct ancestor — as well as Peter Ivanovich Dorofeyev, Pavel Vasilyevich Planidin, and Semyon Efimovich Chernov prepared to burn all the Kars Verigintsi’s armaments. The fire was lit. As it grew, burning the weapons, hundreds of gathered Doukhobors stood surrounding the blaze, singing and praying in a protracted moleniye (mass) that went on continuously until noon the following day. In Kars, the Burning of Arms was a success.

In Elizavetpol, the Verigintsi faced opposition from the Gubanovtsi, who informed authorities of the Verigintsi’s plans. As a result, local police, Cossack cavalry, and mounted frontier guards (Lef): A family photo c. 1920. The man on the lef is Matvey Vasilyevich Lebedev. Next to him is his wife, Vasilisa Nikolaevna, and their three children (l-r) Agafiya, Marya, and Vasya. Courtesy of BIRCHES Publishing.

(Right): Peter V. Verigin (sitting) in exile, c. 1890. With him (l-r) are his brother Vasily, sister Vera, and Vasily Obedkov. Koozma Tarasof Collection. From Confessions of a Doukhobor Elder, Doukhobor Heritage, doukhobor.org.

Winter 2024 7 Flame

were present at the Elizavetpol Burning of Arms and proceeded to arrest, beat, and lash the Verigintsi participants. Approximately 100 men were arrested, 80 of whom were men who threw their reserve tickets — conscription tickets that identified the Doukhobor men with an active role in the Tsarist military — at the feet of the Tsarist oficials. The others detained were elders identified as ringleaders. Still, the worst repercussions came to those in the Kholodnoye region, which had the largest population of Doukhobors, including the largest population of Gubanovtsi.

Like in Elizavetpol, the Gubanovtsi sought help from authorities — such as the regional governor — to intercept the Verigintsi, as the Gubanovtsi were paranoid that the Verigintsi were preparing to attack them. The governor accepted this and sent a Cossack troop led by Captain Praga to investigate. Upon locating the Doukhobors and observing them in prayer, Praga requested they accompany him to see the governor. The Doukhobors refused, as “they were in the middle of a prayer service and could not leave.”

Unable to sway the Verigintsi, Praga attacked. Initially unsuccessful in trampling the Verigintsi under the Cossack horses, Praga viciously lashed the Verigintsi with a nagayki — a military whip of long leather lashes with lead tips — ripping at all those it struck.

To prevent further violence, the Doukhobor elders agreed to see the governor. Praga and the Cossacks continued to use the nagayki on the journey back. Some soldiers dragged the women, who refused to leave the men, by their hair when they fell behind. Still, as the Verigintsi walked, they sang a psalm and did not give in to the cruel treatment.

When the herded Verigintsi reached the governor, they unexpectedly escaped further immediate violence at his hands; the Verigintsi were ordered to their homes to await further instruction, but they were not safe yet. Kholodnoye Doukhobor villages were occupied for two weeks under martial law, by order of St. Petersburg. Under this period of martial law, Praga and the Cossacks had permission to act as judges and executioners, determining what constituted both insubordination and punishment. Beatings, public floggings, and the rape and gang-rape of women and girls occurred over this period; young men who discarded their reserve tickets and elder ringleaders were sent to penal battalions while all others were told to “pledge allegiance to the Tsar… [or] lose all normal citizens’ rights and be subjected to mass internal exile.”

None of the Verigintsi agreed, and

approximately 4,500 of the Kholodenskiye Doukhobors were exiled, isolated from all others, and forbidden from receiving help from anyone willing. Consequently, malnutrition, poor hygiene caused by inadequate shelter, and drastic changes in these groups’ surroundings led to the spread of disease. Between 1895–1899, an estimated 1,500 Verigintsi Doukhobor lost their lives because they refused to abandon their beliefs and surrender to the violent demands of the Russian Tsar.

A new life

World-renowned writer Lev Nikolaevich “Leo” Tolstoy’s eforts to draw attention to the treatment of the Doukhobors, helped raise funds for the Doukhobor exiles to immigrate to Canada via the publication of his Resurrection (1899). There, they hoped they would be allowed their communal lifestyle, exempt, unconditionally, from military service. During 1899–1905, over 8,000 Doukhobors of the Verigintsi Party had immigrated to Canada.

Although this would not be the end of their struggles, the Doukhobors had done what so many could not; facing war and violence, the Doukhobors said, ‘No, we will not betray our values — we will not save our lives at the cost of another’s.’ With the fires that destroyed their armaments, the Doukhobors emphatically manifested their refusal to accept anything less than a peaceful,

Five photographs in one frame: Peter Verigin, 1881–1939 (centre), Peter Verigin, 1859–1924 (top right), Lukeria Kalmykova (top lef), Leo Tolstoy (bottom lef), and one Doukhobor woman (bottom lef), c. 1925

Courtesy of Doukhobor Collection of Simon Fraser University.

community-based existence. With their strong conviction, the Doukhobors lef a legacy of non-violent resistance to militarism and war unparalleled in history.

In the decades following the Doukhobors’ settlement in Canada, mainly in Southern British Columbia and Saskatchewan, those who reside outside of the regions called home by Doukhobor descendants have largely forgotten the stand bravely taken against forced participation in the Tsarist military, much less remembered who the Doukhobor are. In today’s political climate, as tensions amongst nationstates continue to escalate, now more than ever, the historical actions of the Doukhobors cannot be forgotten.

For those unwilling to live in a world fraught with seemingly never-ending conflict, the bravery, strength, and resilience of the Doukhobors during the Burning of Arms — as they held strong against military servitude to the Tsarist empire, withstanding immeasurable violence while maintaining their conviction — is an event to inspire, and a model to follow.

8 The Varsity Magazine From fre with peace

Writer: James Bullanoff

Illustrator: Medha Surajpal

Writer: James Bullanoff

Illustrator: Medha Surajpal

IDeath of a performance actor

A journalist’s memoir of switching majors

never thought of myself as a writer. Those who know me well probably wonder why I keep reiterating this, but for context, I never had faith in my writing ability. I always assumed that my low high school English grades translated to my writing. Little did I know that the thing that would drive my future passions — the flames that burn inside each of us — would be writing.

Throughout my journey to discover what I was truly passionate about, my passions changed constantly. I would jump around between diferent fields of science, and there was even a time when I believed that theatre would be my passion — a fact that ofen shocks people to this day. But then COVID-19 happened — the virus that completely reshaped the world in many drastic ways, from impacting business and schools, to changing the way we spend our time.

While many expressed disdain for the pandemic, I saw the brighter side of it. I took a break, worked for a year, and came back to UTSC, where I discovered a new door waiting for me to be opened. Eventually, I found a new passion.

I started to think about this, the idea of changing passions, and what must’ve been a feeling that I’m sure many others faced. In an institution so focused on grades and a belief that a piece of paper would shape your future, I figured it was about time I told the story of how a theatre kid became a journalist.

Setting the stage

My passion for theatre started at a young age, when I would watch movies with my parents and recite every line characters would say. I had played around with the idea of becoming an actor until I fully committed in high school to pursue it.

I still remember the fondness I have for being on stage. I was Shakespeare in The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (Abridged), and I was almost Warner for Legally Blonde, the musical. While I didn’t have an extensive

background in plays, these moments really made me excited about the industry.

The only problem was that a global pandemic happened: for many, this completely reshaped their entire worlds, and for me, it caused me to question my last year of high school. All of my classes were moved online, and theatre just didn’t feel the same.

This is where my doubts kicked in once again. Taking a gap year and getting accepted to UTSC made me realize that it might be time I explore other options. This would be the starting point for how I discovered writing.

Changing course

The phenomenon of experiencing a drastic change is not unique to me. Barry Freeman, an associate professor of theatre and performance studies at UTSC, spoke to me about how he discovered theatre and stuck to it.

His story began as a UTSC student studying astronomy. Afer being dragged into a play by someone in high school, he decided to take a theatre course early on in his undergraduate degree. One thing led to another, and he eventually developed a greater passion for theatre.

However, job security is ofen a big hurdle when considering long-term careers. Freeman mentions that there is a perceived security with occupations in the sciences, but a perceived insecurity with careers in the arts.

“If you [start with] an idea that ‘I’m going to work in the sciences somehow’… you couldn’t imagine a more precarious, less paying, not very solid career to go into than theatre,” he said.

A 2019 study published in Nature Communications that collected data from actors listed on IMDb found that 90 per cent of TV and film actors are unemployed at any given time, while just two per cent actually make a living in the profession. Since roles only last so long, many have to take on side jobs in order to make a living.

And in an ever-changing economy riddled with problems such as grocery bills and housing prices that seem completely unattainable, money is essential. So when some people choose their degree, they choose what seems financially viable and stable — instead of pursuing our passions, we decide to play it safe.

Despite all this in mind, Freeman still chose to take the harder option. “It wasn’t a choice for me… When I was in the theatre, [it was] very clear to me that I need[ed] to keep doing this. It’s that simple… I just was so enthralled by the challenge of it.”

People spend a huge chunk of their life working. The average American worker spends 34.4 hours per week working. That’s roughly 90,000 hours at work over your lifetime, meaning people will spend a third of their life at work. So while finding a job you enjoy seems obvious, it’s the leap of faith that scares people.

“People think of their whole education this way… ‘I get my degree, and then I’ve got the thing. Here’s my thing. Okay, what comes next? What door does this open for me?’ And I tried to just shatter that idea,” said Freeman.

Breaking news

Similarly to Freeman’s story, I took a few writing courses in my first year and discovered a new program that I instantly fell in love with — journalism.

If I wanted to work in journalism though, as professors and special guests in the journalism sector told me and my classmates, it was crucial to start writing as soon as possible. If I wanted to get anywhere in this industry, I needed to act fast. That was when I first heard about The Varsity I still remember my very first article: I wasn’t even close to being a news reporter yet, so I took a pitch from the arts section about Elon Musk taking over X, formerly known as Twitter. This would be the lighter fluid that sparked my fire for writing.

My time at The Varsity has shaped not only my reporting but also my experience in journalism. I found this new obsession with telling stories and keeping up to date with current news events. I love my job, and reporting for the Scarborough community as the UTSC Bureau Chief has given me some of my best experiences in the university career so far.

Even as a journalist specialist at UTSC, all I eat, sleep, and breathe is news. I look forward to the internships and assignments that get me out in the field and am thankful for the opportunities to do so.

Winter 2024 9 Flame

While it’s worked out for me so far, journalism is not for the faint of heart. There have been mass layofs in the industry recently, such as the 600 people terminated from Metroland Media Group or CBC/Radio-Canada’s cutting of 10 per cent from its workforce due to budget shortfalls.

The Canadian media landscape isn’t particularly an inviting one, either, especially with the ongoing battles of Bill C-18 and the Federal government’s fight for news organizations to be paid for their links.

With all this, the idea of working in the industry becomes an unpleasant thought. While the passion is there, ofentimes we realize that things change. One of my coworkers, Mekhi Quarshie — the managing online editor here

at The Varsity and last year’s sports editor — spoke to me about his experiences moving up the ladder and his own personal growth throughout the years.

“I almost lost my love for writing. Ever since the end of my sports editor year till midsummer, I didn’t write that much. Because my job didn’t require it and I just didn’t know what I would write about,” said Quarshie.

Discovering that one of my colleagues felt like they were losing their touch really surprised me at first. It wasn’t until I reflected on my own changes that I realized that, for some, the same passion that I felt can fade to embers.

“When you’re an associate, when you’re an editor, you’re writing the articles, you’re coming up with the ideas. But then when your

paycheck starts to increase, your creativity starts to decline… there’s not that pure joy that I had as a sports editor,” Quarshie said.

Quarshie felt that in an industry with too much turbulence, he couldn’t fully commit to it. “I wish I could be super gung ho on journalism and only think about my passions. But for me, I have to also think about the money.”

Even those studying the program are facing dificulties. Back in November, Humber College announced it would be pausing its journalism program amid low enrolment and a changing landscape. While it hopes to start up again in the future, it’s devastating to the new generation of journalists to learn just how tumultuous journalism programs themselves are.

Even though Quarshie works for The Varsity

10 The Varsity Magazine

Death of a performance actor

and published a piece this year for the Toronto Star, his passion still difers from what he wants to pursue as a career. “I love journalism, but I’m not the type of guy that wants to be scrambling for a job afer I graduate. I really [like] stability.”

Three-quarters into a double major in journalism and political science, he still has the idea in his pocket. However, the job security that some programs provide does exist, and many base their choices on what uncertainty they can handle.

The path ahead

In writing this, one of my biggest takeaways is

realizing just how much experiences can shape our passions. Each person has a unique set of circumstances that leads them onto a path, to a goal that they pursue. No matter where the path goes or what’s in store, everyone takes it, and everyone does things when they need to.

Becoming a journalist was, by all definitions, an accident. I’ve had the honour of meeting an incredible array of reports and instructors who have shaped me on this path. It was never something I planned, but it was definitely what found me. In a time of uncertainty, I made this weird thing work, and so far it seems to be the

thing I will be obsessed with for the rest of my life. Passions will constantly come and go; learning that is really what university is about. Even when things feel uncertain, we all find our path eventually. No one degree will make or break you, but I think it’s about finding what you enjoy and sticking to it. No matter what your path is or how jagged your road gets, I encourage you to keep walking, because eventually you will find your own flame.

Disclosure: James is the UTSC bureau chief for The Varsity.

Flame Winter 2024 11

Writer: Chris Zdravko

Spicy food

Strengthening myself with spicy food

Photographer: Ashley Jeong

Ihave developed a burning passion for hot foods, more so than many.

As a child, if I misbehaved, my Mum would threaten to put pepper in my mouth. Eventually, she did. I think I cried.

Whenever I watch Hot Ones on YouTube, the show where the host interviews celebrities while they devour spicy wings, I think about the thrill of being a guest. I would love it. Most celebrities take a single bite of each wing. I would eat them all to the bone. Practically all those sauces look delicious. I would not hold back on the milk though.

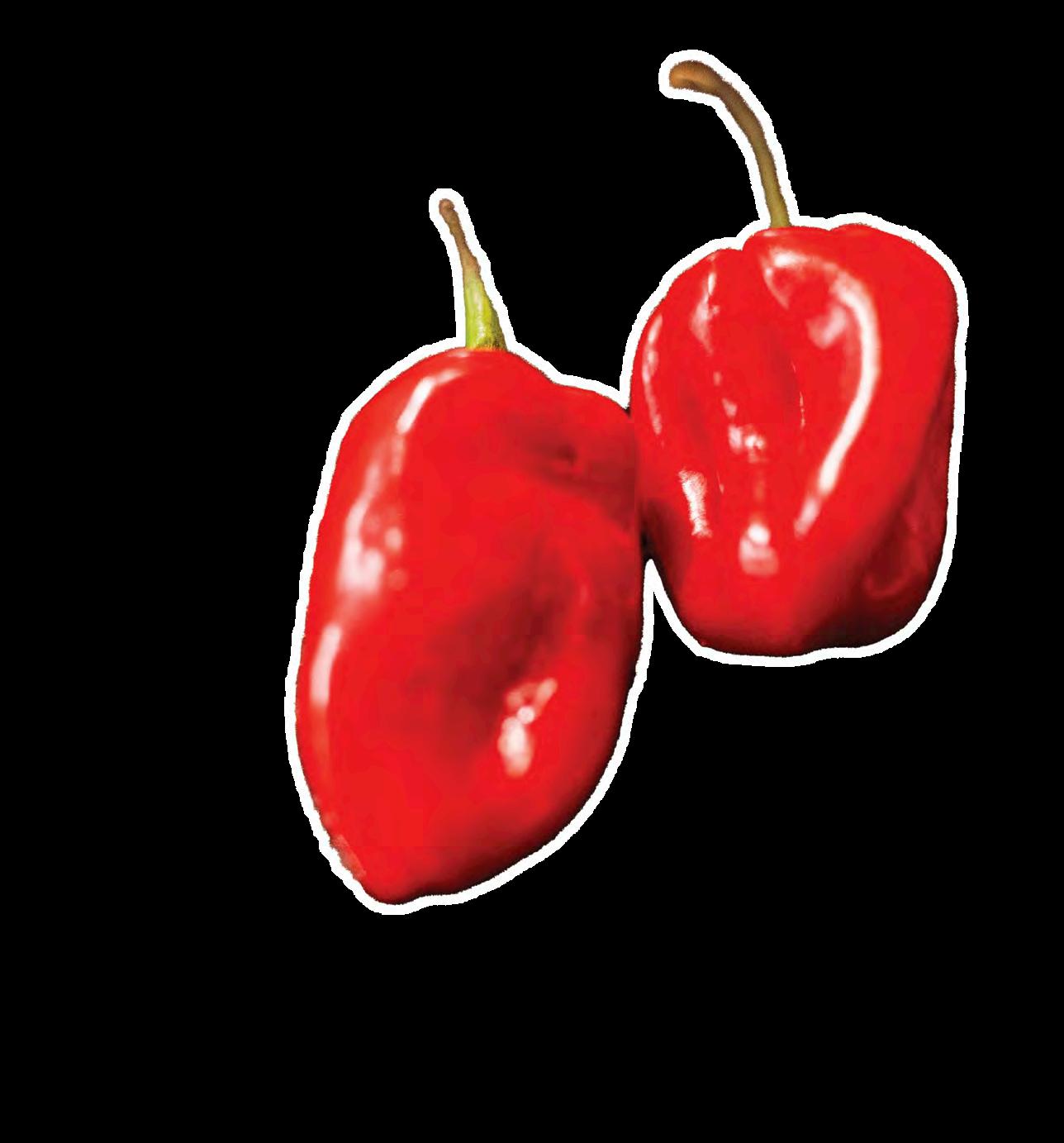

I love Osmow’s. When I eat there, I order ‘Scorchin’ Hot’, the hottest spice level. Every time the restaurant staf expresses concern for me, I reafirm to them that I want a big kick. Yet, when my food comes in, it’s not as spicy as I would have liked. I recall a year or two ago, when I was ordering vindaloo at an Indian restaurant, the waitress assumed I wanted mild spice. I had to confirm with her that I wanted it spicy. I recently asked my Mum to pick up Tabasco sauce from Costco, and I have been throwing it on many meals, from sausages, to salmon, to potatoes, to salad.

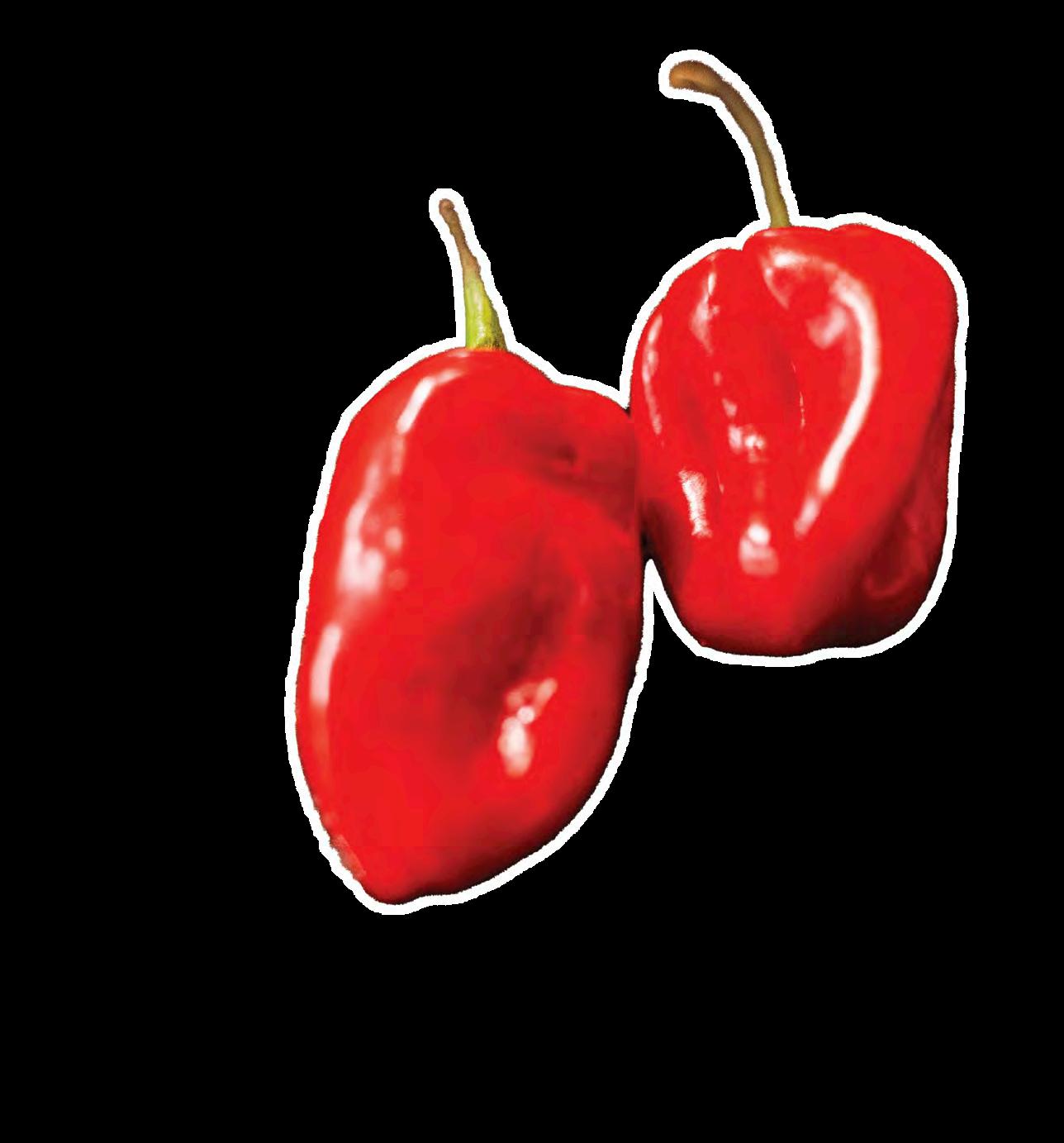

I have many anecdotes about my love for spicy food, and many can say the same. Our afinity for hot peppers as humans intrigues me. Why do we enjoy eating things that set our digestive systems on fire? Why eat plants that cause pain?

I have researched the topic thoroughly, spoken with food experts,

and tried unique spicy dishes in the GTA to try to answer these questions. Throughout my journey, I learned that our love for spicy food ranges across cultures and flavours, and for many, eating hot foods is a form of pride.

Scoville science

When discussing peppers, it is useful to know two things: what makes them hot, and their

feel when we eat them. The more capsaicin in a pepper, the spicier it will be. This chemical is also the main ingredient in police-grade pepper spray.

In 1912, American pharmacist Wilbur Scoville invented the Scoville Scale to quantify a pepper’s heat level. He created an experiment and called it the Scoville Organoleptic Test. To conduct the test, you need a pepper, an

12 The Varsity Magazine Spicy food

the capsaicin from the pepper into an oil using the solvent. Then, you add a drop of the oil to the tongues of the tasters. If they taste heat, you add some of the sugar water to the oil. Then you keep diluting by a regular amount until none of the tasters can taste the heat. Scoville assigned a jalapeño an SHU of 10,000, meaning he had to dilute it 10,000 times before nobody could taste any heat.

The problem with Scoville Heat Units is that they are based on subjective measures. People have varying spice sensitivities, based on varying exposure to spice and genetics. Peppers also vary depending on their growing conditions, age, and lineage. A jalapeño grown in Mexico may taste diferent from a jalapeño grown in China. A pepper’s SHU is more of a rough estimate than an exact calculation. Scientists have come up with a more objective test for measuring capsaicin levels, called high-

The #Onechipchallenge received over two billion views on TikTok. It features internet users of all ages eating the spicy chip and enduring the dreadful heat with entertaining reactions.

“People [take] pride in the fact that they can wolf down food that makes other people burst into tears.”

The chip and any food with an SHU of one million or higher are no joke. There have even been instances of teens and adults possibly

spice. Some say sweet food helps too. Pepper junkies should have these by their side when they are about to battle the heat of a super spicy food.

Capsaicin culture

Dylan Clark is an anthropology professor at U of T St. George with expertise in foodways, meaning the eating habits and culinary practices of people, regions, or historical periods. He is also a spicy food lover. In an interview with Clark, he told me that food is universal in cultures around the world, and it doesn’t just have to do with sustenance. “People see themselves in food. They see gender, race, and religion,” he said.

On the universality of spicy food, Clark commented that “it is a form of food that people naturally find challenging to eat, say, when they are two years old… but then learn to like it.” Clark discussed how in some countries and cultures, parents ofen raise their kids with hot food as a regular part of their diet. This allows kids from these cultures to build a resistance to hot food from a young age, and become more tolerant of it than kids from other parts of the world.

Spicy foods do have their health benefits. Chili peppers, for example, have antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties. They also can speed metabolism, reduce muscle inflammation er workouts, and promote brain health.

Clark observed that not only is spicy food universal but the ability to endure it is a source of pride for many cultures. “People [take] pride in the fact that they can wolf down food that makes other people burst into tears. It’s a marker of ethnicity and nationality — because it excludes people. Because some people literally can’t handle the heat.”

When I asked Clark about the connection between hot food and masculinity, he said that gender is a performance that people play, and that “people use food as a vehicle to perform those things.”

He discussed how foods in some cultures are seen as feminine, like ice cream in Japan. “In some contexts, people think that spicy food makes you a man. In some contexts, they don’t. In France, eating spicy food doesn’t prove you’re a man. A lot of French people

Winter 2024 13 Flame

that I know think that spicy food is low-quality cuisine.” He told me his French friends enjoy meals that are fine-tuned to satiate their taste buds rather than meals overloaded with spices, which may be deemed “lowbrow” or “lacking artistry.”

Clark reminds me that these cultures are diverse, and there is no country where everyone likes or dislikes a particular food.

When I interviewed Canadian food journalist, David Sax, he commented on perceptions of a new interest in spice. “Spicy food is nothing new. What’s new is a cross-cultural interest in it, and a persistent hunger from diners, shoppers, chefs, and food brands for a new way to spin a take on spice. So each season you get a new spice flavor profile [like gojuchang or ghost pepper] and a new application for it [like] an interesting drink at a cool cocktail bar or a new flavor of Doritos.”

“People eat with their imaginations and food trends have this way of sparking that imagination over and over again. It keeps it fresh, even if the basic taste remains very similar. So today, it’s sriracha, yesterday was Tabasco, and maybe tomorrow, it’s zhug. That’s what makes modern eating and cooking and food culture interesting. It doesn’t stay still.”

Hunt for heat

My interest in spice doesn’t stay still either. Si Shuan, or Szechuan peppercorns are notorious for their unique flavour, a mix of spice with numbing properties. I tried it for the first time at Magic Noodles on Harbord Street. I ordered their Szechuan Friar, and it was like nothing I’d ever tasted before.

The dish was made with noodles, bok choy, chicken, onion, carrot, and green pepper, mixed together and seasoned with Szechuan pepper.

In the first bite, I tasted the heat, but at the same time, I felt the Szechuan’s cooling, numbing, almost minty properties, allowing for a great blend. Kind of like fire and ice. It was delicious. I felt a tingling sensation in my lips. The noodles tasted like magic. It also paired well with the Chinese beer Tsingtao, which tempered the spice.

Duf’s Famous Wings on College Street is known for its signature hot sauces, Death and Armageddon, which originated in Toronto. Their “Wall of Pain” encourages brave people to take on spicy wing-eating challenges. The record for most Armageddon wings eaten is 69.

The Dufney family started the company in 1946 as a tavern in Amherst, a town north of Bufalo, US. In 1969, the family began selling chicken wings, which people hailed as the best in Bufalo. Because of its closeness to the Canadian border, the restaurant was popular

among Canadians. Twin brothers Hy and Rob of the Erlich family approached the Du to discuss expanding their restaurant into Canada. In 1998, Du in Toronto, bringing their beloved sauces from America. Today, there are three Du branches in Ontario, and two of them are located in Toronto.

Loren Erlich, the manager of Toronto’s College Street location, told me the Death and Armageddon sauces are a family recipe made of a variety of peppers, including habanero and scotch bonnets.

“Our Death and Armageddon sauces were added features to the menu when we opened in Toronto. At the time, super hot was the hottest sauce, and there’s a lot of multiculturalism in Toronto, so there were some cultures that didn’t find the super hot hot enough. So my mum and my aunt started working on recipes to develop that.”

It has been a heated journey as I searched the GTA for hot food and spicy perspectives. I wish I was able to find some Bird’s Eye chilis, habaneros, or scotch bonnets, but that might just be a tale for another time. I’m glad I was able to learn so many new things about hot food, try the hottest wings I’ve ever had, and experience the magic of Szechuan cuisine. I will admit: handling

14 The Varsity Magazine Spicy food

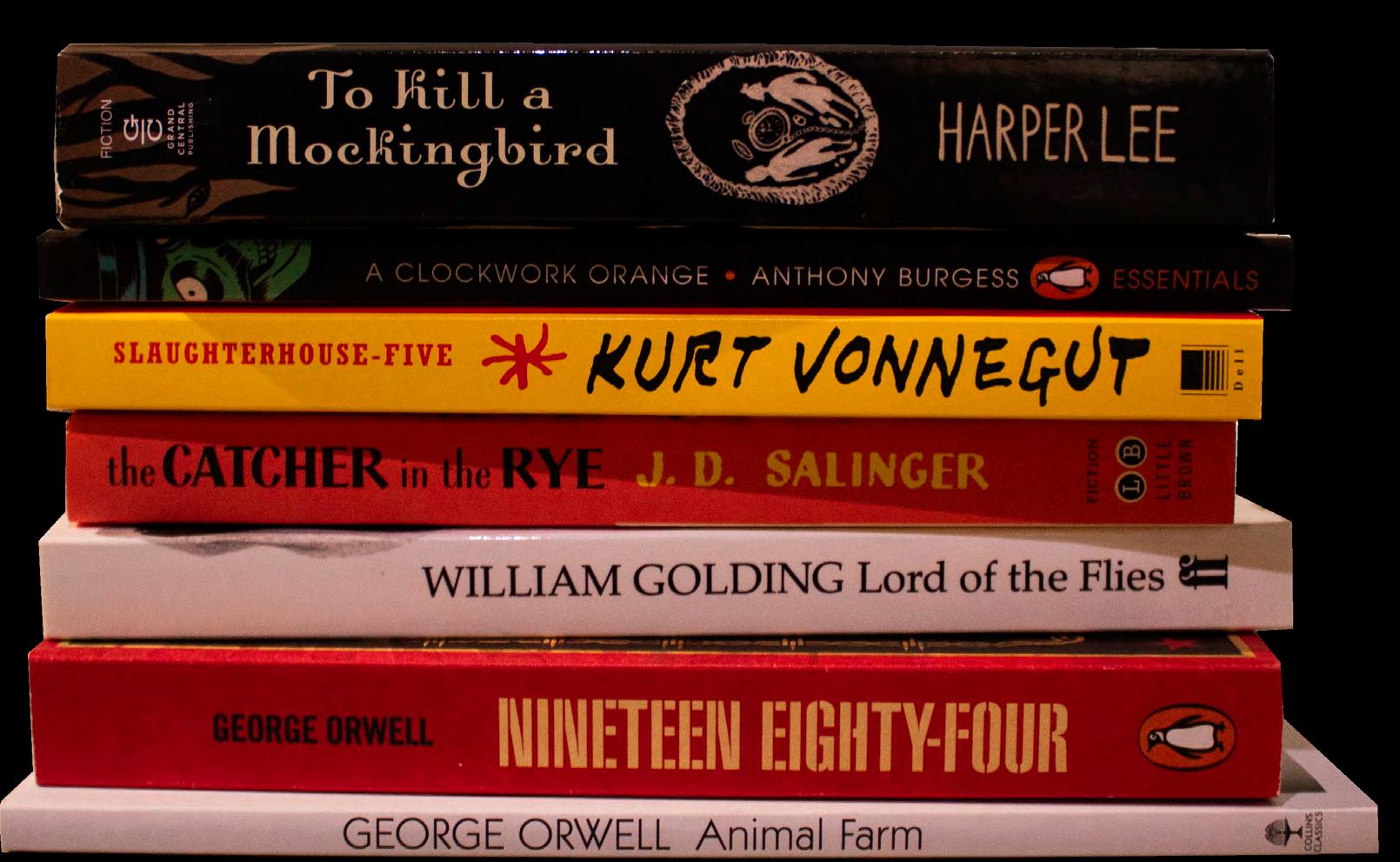

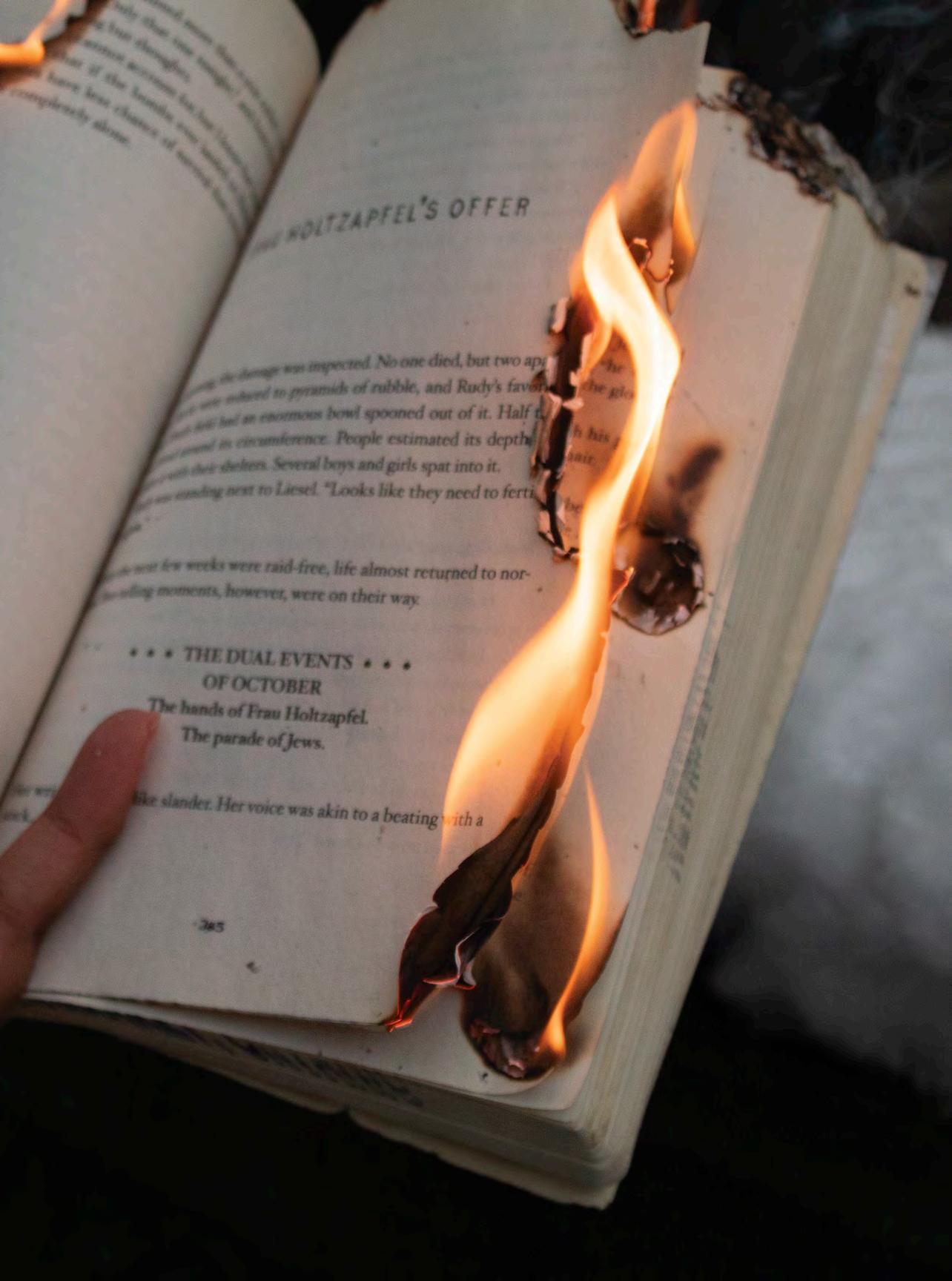

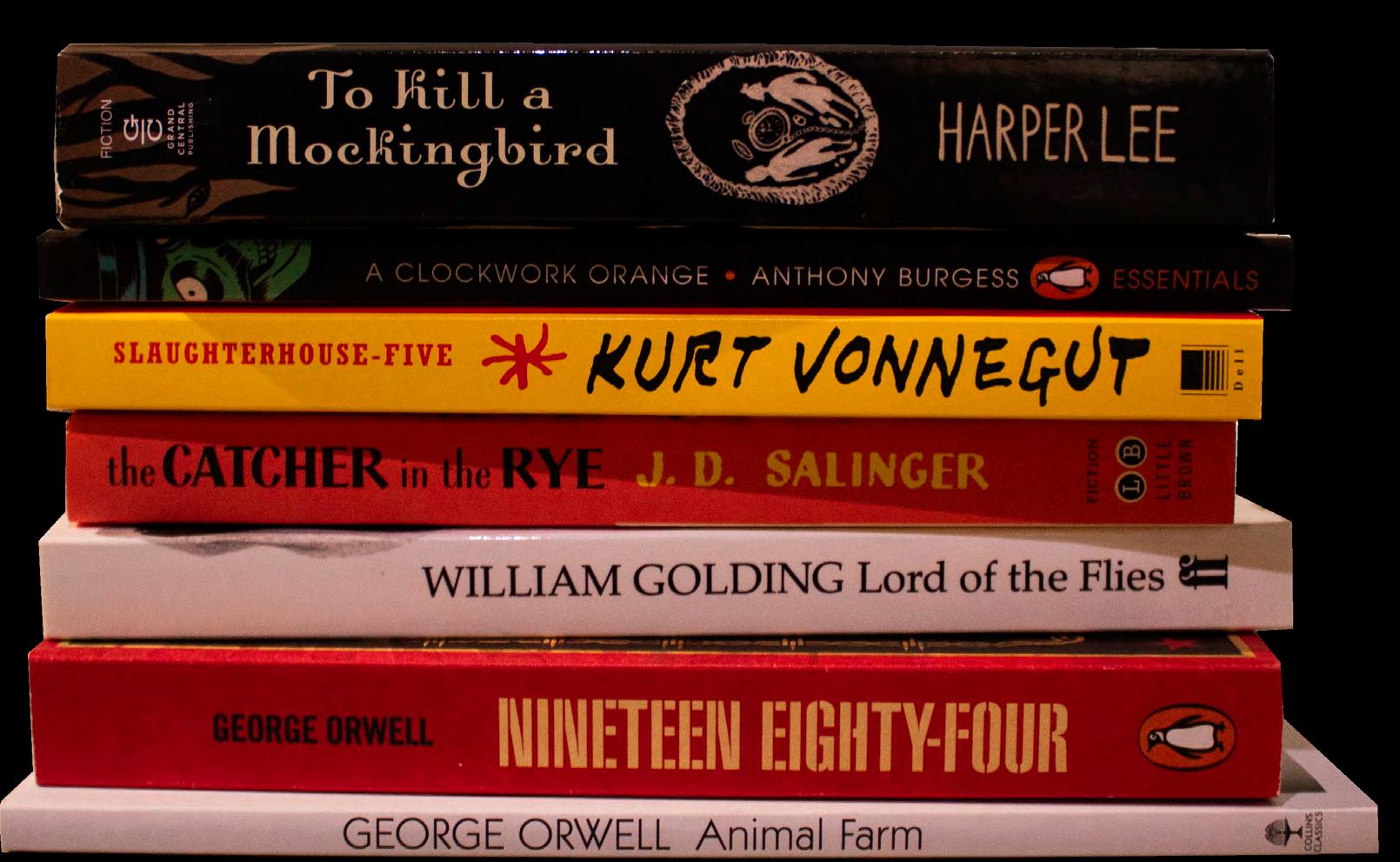

Book bannings matter, and Canadians need to take them more seriously

Writer: Philip Harker

Photographer: Ary Kwun

If you’re reading this, you probably haven’t been in a public school for a while. So here’s a refresher on an all-too-common occurrence in schools: sometimes, parents make a fuss upon learning which books their child will be reading. For whatever reason, they may find the content or themes of a novel highly objectionable and make a complaint about, or ‘challenge,’ the class’ reading material. And sometimes, they will win that ‘challenge,’ and the book will be banned from the school’s circulation.

It’s not just parents who challenge books. Sometimes outside organizations initiate book bans, such as religious or political interest groups that may or may not actually have a student in the classroom.

It’s also not just classrooms. Books are challenged in school libraries as well as in public and academic libraries.

We know of these statistics thanks to data collected by the American Library Association’s

(ALA) Ofice for Intellectual Freedom — the oldest and largest library association in the world. Established in 1876, intellectual freedom is one of eight key action areas that the ALA focuses on. Since 1990, it has been documenting book challenges and bans across the US, bringing the act of book banning into the limelight of today’s politics. But it’s also wrong to imagine this movement as being a purely American issue. The Canadian Federation of Library Associations — a nonprofit that serves as a united voice for Canada’s library community — has its Intellectual Freedom Committee, and though its data is sparser and needs to be made more available, it documents many challenges to books from libraries across Canada.

I feel like only a certain type of person seeks to control the free flow of information and intellectual discourse, usually by stamping out information and ideas that they dislike. Unfortunately for them, the laws of free

speech and expression make it dificult for governments to censor published work.

I am under the impression that these people have a very strong belief in how the social order should be structured. They are not interested in debating or arguing with the ideas at play. They are only interested in blocking these ideas and making them inaccessible to protect their vision of the social order. So they grasp at straws, trying to enforce this non-access through the few means they can.

Some would call these people “fascists.” Personally, I prefer to refer to this type of character — the type that writes heated letters about The Glass Castle or shows up to a school board meeting to complain about a Toni Morrison novel — by a diferent name. These people are anti-intellectuals.

There’s not really a better way to describe them. The type of people who think that some literature needs to be sequestered away, that some knowledge must be controlled by a

Winter 2024 15 Flame

select few — these people are free-thought opponents of the highest order. I don’t think they care for the well-being of children or the good of the public discourse. They seem to believe that humanity’s best path forward is through a top-down control of the narrative and the suppression of critical thought.

If book challengers really had any belief in learning and intellectual discourse, they would trust teachers and students to come up with sound conclusions on their own. Anti-intellectuals are quick to argue that they don’t trust teachers because they don’t want their children to be indoctrinated by politically motivated educators. I think we adults have far too little faith in the youth and their capacity for complicated thinking. No teenager is going to read Looking for Alaska and decide to go out and have bad and unenjoyable oral sex, nor are they going to read accounts of Vietnam in I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings and engage in “antiwhite” behaviour — whatever that means — as some Maryland teachers phrased it in a 1998 challenge.

Literary depictions of sex, racism, gender, abuse, drugs, and other such subjects don’t directly inspire devious or immoral actions in youth. This is a lie that was made up by anti-intellectuals to control education to suit their agendas.

The initial problem with this logic is so obvious to me that I’m honestly surprised more people don’t bring it up: it presupposes that kids get their information and their worldviews exclusively from the books in their school libraries. If you seriously believe in the argument that ‘bad books cause bad behaviour,’ you also believe that books are the primary driver shaping youth culture.

According to Pew Research Center, nearly 30 per cent of American youth between 13 and 17 “never or hardly ever” read for fun. The conversation about the decline of reading is much older than the current day, and young people seeking entertainment have more options than ever before — TV shows, movies, video games, and also more recent cultural movements like social media and online streaming.

If any format of media is having a serious impact on youth, it’s not books. For every “immoral topic” that might be argued to appear in a book, it has just as many appearances on TV, in movies, and on YouTube or TikTok. So the crusade against books in specific seems just a tad disingenuous.

That said, many book challenges don’t arise from school libraries. They come from

classrooms — generally, English classes in which the challenged books are actually required reading for the students.

There’s a common trope of English teachers being esoteric in their interpretation of literature. The old joke, “Why are the curtains blue?” — a hapless English teacher trying to get students to uncover the literary significance behind a set of blue curtains, where, in fact, the curtains were just blue — comes to mind, exemplifying the stereotype of teachers forcing kids to seek literary meaning where none actually exists.

But so much of literature’s value lies not in these superficial analyses but in how fictional stories align with our own stories in the real world. Literature is supposed to challenge us and help us imagine the world diferently. Great books ask how sure we are of the world and how we fit into it, and then they ask us why.

“Intellectual freedom needs to become a better-known issue.”

It’s tempting to argue that books are just entertainment pieces — distractions like any other. And though some books certainly have more intellectual value than others, that ruling is not for the masses to make. It’s for educators — the professionals we employ decide which works are better suited for a classroom. If teachers cannot be free to make these choices, education as a whole will sufer.

The kinds of topics that cause antiintellectuals to challenge books are ofen things that they find inappropriate — sex, drugs, and the like. I can admit that this is noble, but it is misguided. As we’ve discussed, such depictions don’t provoke bad behaviour. In fact, they’re ofen meant to do the opposite.

If literary education aims to help students understand the world, then the literature they study has to actually include issues from the real world. In real life, lots of people have marginalized identities that shape their experiences in the world. A lot of people have substance use disorders, are locked in abusive relationships, or have unhealthy relationships with sex and attraction.

These are real challenges that students will confront in their lifetimes — perhaps the greatest challenges they will face, greater than any algebra problem or chemistry lab. Classrooms ofer kids a chance to learn about these challenges in a safe environment so they can think about them critically before

they enter adulthood. Kids who learn about the evil of racism or the immense sufering of addiction are going to be better equipped to understand them in the real world than the ones who are shielded from these ideas.

But anti-intellectuals are unwilling to consider this. They have a worldview to maintain for themselves and others. They suppress inquiry and curiosity because they are utterly terrified that the new generation might enter the public conversation with ideas — generated by critical thought rather than propaganda — that stand in opposition to their own.

The emergence of public education, this idea that everyone should receive free schooling, was an enormous achievement in our history. Education is about far more than the learning and success of any student; it’s also about the rest of us. In the long run, everyone benefits from a population of welleducated people who can think critically about themselves and about the world.

Anti-intellectualism spits in the face of this achievement. Behind the euphemistic shield of “protecting students,” anti-intellectuals seek to insert an agenda at the expense of the integrity of education. When parents, administrators, and lawmakers allow antiintellectuals to enforce changes to classroom materials, it sets the precedent that politics should be allowed to permeate classrooms.

This isn’t speculation. For example, Florida saw 194 books challenged across various schools in the first eight months of 2023 — and conservative politicians have also spent the last year hammering away at high school Black history courses, as part of a larger efort to restrict education on marginalized races and genders in the country.

If we allow politics and reactionary movements to directly change how schools operate, we are betraying the core value of public education. Young people whose education is being curated by antiintellectuals rather than trained educators are not being taught to form arguments and critically examine literature. They are being indoctrinated into an inherently biased worldview, leaving them dangerously unequipped to navigate the ever-morecomplicated world that school is meant to prepare them for.

It’s nothing new to argue that the world is getting increasingly polarized in not just in government but also in our social circles and dialogues. It ofen feels like people are more fractured and divided than ever before. Debate and disagreement are extremely important to the creation and maintenance of a healthy

16 The Varsity Magazine On intellectual freedom

social order. However, there is a diference between a well-informed public conversation and the extremely partisan shouting match that seems to dominate the current political moment.

Intellectual freedom needs to become a better-known issue. Teachers and librarians need more support from their communities in their autonomy, and the public needs to be better informed of book challenges and their outcomes.

The future of this public conversation isn’t just some figurative idea; the future of politics is very real — they are the kids growing up in this moment of great anti-intellectualism. And right now, they’re sitting in their high school English class being told that the board has banned The Handmaid’s Tale because it depicts sexual abuse and that they will have to read something else.

Personally, that doesn’t fill me with confidence. Whatever the path forward is for our democracy and social cohesion, it seems that without intellectual freedom, our public conversation will never truly be free.

“Literary depictions of sex, racism, gender, abuse, drugs, and other such subjects don’t directly inspire devious or immoral actions in youth. This is a lie that was made up by antiintellectuals to control education to suit their agendas. ”

Winter 2024 17 Flame

In search for warmth

My mother taught herself the language of love

It

took me years to understand her

Writer: Hasna Hafidzah

Illustrator: Zoe Peddle Stevenson

In 2017, I finally visited my mother’s childhood home in the Arun compound in Lhokseumawe, Indonesia. The compound, a gated community housing employees of the state-owned liquefied natural gas (LNG) company, had been mostly unoccupied since its last LNG shipment in 2014. If it weren’t for my mother, I would have probably avoided entering the housing complex altogether. Who knows what lurks behind its forest? The Arun compound my mother knew was reduced to skeletons: its streets empty, its houses abandoned. The only visible signs of community life were the street vendors camping on the rim of a football field.

My mother lef Arun in 1994. Afer 23 years, she still remembered every turn, roundabout, and junction by heart. Our route was to my mother’s old house, elementary school, and middle school. My mother treasured these places, and by observing them, I wanted to learn more about her. I assumed that her commitment to motherhood and her sacrifices of becoming a housewife for 15 years were linked to this specific time of her life.

When we returned, my mother uploaded photos from our visit to her Facebook album. To many, her post probably resembled ads of abandoned houses sold for renovation. She named the album “Throwback: My Childhood Neighborhood.” The caption read: “Everything changed, but all the beautiful memories are tucked neatly in my heart.”

Despite the tough times my mother had been through, I deeply respect her for never complaining about her childhood to her children. In some ways, I believe that motherhood was her attempt to compartmentalize and preserve what’s lef of the past. But I still wonder what motherhood actually means for her.

When I asked her this question, she gave

a bittersweet smile and said, “It’s weird — it feels a lot like searching for a lost sense of warmth.”

When I asked my mother what she remembered about my grandmother, she replied coldly, “I don’t remember what it felt like to be loved by her.”

I turned to myself for answers: what about me? What do I remember about my mother? I remember many things about her. I remember how she stayed up late one night, leaning her head against the crooked, checkered wardrobe cabinet just to finish reading Totto-Chan: The Little Girl at the Window. I remember we would take out our flat futon mattress and camp in the living room for Harry Potter movie nights, complete with snacks and tea. I remember the elaborate surprises for my birthdays every year. The key: diferent year, diferent cake flavour.

I also remember how she screamed in distress, locked up in her study, writing the final parts of her PhD dissertation in four days. It felt like the longest four days without her. Now, I spend an average of 21 days with her every year. And it feels normal, somehow.

When my mother was interviewed for a lecturer position in one of the masters programs at the School of Strategic and Global Studies at the University of Indonesia, she phoned to tell me all about the interview, down to the description of her interviewers. She called when I was in the middle of dinner.

“There was a question about my biggest achievement in life,” she said.

I paused chewing my food to direct my full attention to her and asked, “What did you answer?”

I saw a smile form on my mother’s face. She said, “I told them that my biggest achievement is sending my daughter to study abroad.”

I realize one thing my mother and I have in common: we are both afraid of change. Ironically, we always seem to believe the other person will handle it better. I see my mother as someone who wants to break

away from her past, and who refuses to be a victim in her story. My mother’s conception of responsibility pushes her to make sacrifices. The scary thing about being a parent is not only that it is a lifelong responsibility but also that your children are reflections of who you are.

My mother is so driven in her career because it is what motivated her to break her ties with the past. Since she had been constantly striving for better for so long, I think she’d forgotten what warmth felt like.

“I was idealistic when I was young. I was so fixated on having things done the way I wanted them to be done. I hold myself accountable for my standards, but I should’ve been more aware not to impose the same on my children,” she said.

Being a mother and having a career established my mother’s path to recognition — something she didn’t receive growing up. Motivated to deliver the love

18 The Varsity Magazine In search for warmth

she wasn’t given but knew existed, she aimed to create it for her children. “Afer years of parenting, I learned that success is really not about the high numbers on the report cards or the grand extracurricular achievements. Each of my children has their own success stories, and I’ve

come to terms that these stories look diferent from one another,” she said. Warmth exists within the walls of our home.

I wonder what my mother lef behind and what she kept with her. I acknowledge that people have diferent avenues for self-actualization, and perhaps parenthood is not always one of them. My friend finds it in her work, and others in their hobbies.

I want to be her source of warmth. Afer such a long period of focusing on her children, I think she forgot a lot about who she is as an individual. She needs to relearn many things about herself. I have learned many things about her that she had probably forgotten about herself, and one thing stood out: she has always had the spirit of fighting for herself.

I think that’s the virtue of motherhood. You are growing as a person by raising another human being — someone who teaches you about love and the values of sacrifice, or who will point out things you perhaps do not want to hear but have some seed of truth. It can be scary to see a reflection of yourself in someone who always keeps you in check, but it teaches you to be more patient and self-aware.

At the end of dinner, she turned to look at me. “I’m sorry if I’ve hurt you with my expectations.”

For the first time in my life, I saw my mother as a girl, burdened by the memories of her past which fuelled her lifelong fight for achievement. I saw someone who had put that fight aside, who snufed that flame to tend to another: an act that proved her capable of evoking a maternal warmth she can’t personally remember.

Flame Winter 2024 19

What the women in three Hindu epics taught me about womanhood

20 The Varsity Magazine Feature — Trials by fre

Writer: Ajeetha Vithiyananthan Illustrator: Jishna Sunkara

First, a disclaimer: the following isn’t meant to dissuade anyone from their faith, belief in a higher power, or optimistic nihilism. In fact, more power to you for walking through life’s trials by fire unscathed and stronger for it — I’m sure, one day, I’ll come out the other end too.

I have a fickle relationship with faith. My parents are Hindu by ancestry and choice, whereas I tend to identify as Hindu by ancestry, agnostic by choice, and a convert to any God who’ll take me by exam season.

I won’t go into extensive detail about why I walked of the path to salvation, ending reincarnation, or whatever else. Put simply, I’m a humanist at heart — I believe that I can satisfy my emotional and spiritual needs and follow an ethical life without God or religion — and am determined to stand by my own moral compass.

Nor will I go into how I walk the line between existentialism, nihilism, and absurdism — because I don’t. Every day, at random, I trip and fall — but never settle — into any one of the three philosophies about our life, death, purpose, or rather the lack thereof.

Instead, what I would like to divulge here is my love for the mythos and my unwavering love for my fellow women, mortal and immortal.

My love for Hindu stories was instilled by my parents, explored through Indian classical music, remembered during the excruciating wait for Uncle Rick’s The House of Hades, and like any Gen Z kid when the adults ran out of answers to our unending questions, reignited on the internet. I also grew up adoring the Hindu goddess Durga — a principal form

of Shakti, the divine female energy; the protective mother of the universe; and a badass warrior — and I wish to embody her energy, forever and always.

Aside from Durga, three other female figures also occupy my mind: Ramayana’s Sita, Mahabharata’s Draupadi, and Silappathikaram’s Kannagi. These women share three qualities besides being one of, if not the defining protagonists of diferent Hindu epics. One, they are strong women who endure tough ordeals and refuse to be beaten down. Two, they are women whose ‘purity’ is considered of the utmost importance — but, then again, what woman doesn’t have that in common? Three, oddly enough, they each share a story with Agni, the god of fire.

These women undergo unspeakable trials that involve large amounts of sufering, and their stories eerily echo how I think women are treated in society today.

Fire as creator, destroyer, messenger, and watcher

Fire is a ubiquitous part of anyone’s story — not just those of Sita, Draupadi, and Kannagi, whom we’ll get to soon.

Fire is a natural element of the Earth and one of humankind’s first discoveries. From time immemorial, we humans have been in awe of fire: it keeps the world bright, our food easy on the stomach, and us and our loved ones warm. Simultaneously, we’re terrified of it: painful to endure and sometimes deadly, fires can be weaponized against us, be it by mother nature or fellow humans.

Hence, it follows that Agni has a central role in Hinduism. Agni is ofen depicted in a

deep shade of red with two faces — suggesting both his destructive and generous qualities — riding on a ram and wielding the fiery Agneyastra. And while considered the creator of the fire within the sun and stars, and the heat required for digestion, his humble abode is within wood, among humanity. As fire can be reborn with the friction of two sticks and maintained as long as there’s a steady supply of oxygen, he remains forever young yet immortal.

He’s also the courier between the human and celestial realms. From temple altars to homely shrines, lamps are lit from dawn to dusk in service of the Gods, to whom our prayers and from whom our boons Agni carries. In yagnas and pujas — rituals of fire — his seven tongues are said to consume sacrificial oferings, and the smoke trails signify their path to the gods above. In Hinduism, when people die, their bodies are cremated so that — according to some tales, at least — Agni guides their souls to their rightful destination in the cosmic order.

But to me, his most interesting and markedly diferent role from other mythological guardians of fire is that of the witness. As fire burns in every corner of the world, so does Agni, ever-watching the triumphs and tribulations of humanity. Agni is considered the primary witness for Hindu marriages, as a couple completes their seven vows to each other and the corresponding seven circles around the sacred fire. Because Agni bears witness to all, he’s also considered the best at discerning truth from lies. As such, fire is not only a creator, destroyer, messenger, and watcher, but also a judge.

Winter 2024 21 Flame

Agnipariksha is the age-old practice of making someone walk through fire — or a proximate — with the idea that an unscathed success would indicate truthfulness and purity. It’s horrifying, and yet, the idea and execution of a ‘trial by fire’ isn’t unique to Hinduism, as the term originated from medieval practices. One of the most famous instances is that of Emma of Normandy in mid-eleventh century England, who twice widowed was accused of adultery with the Bishop of Winchester and required to walk across red-hot ploughshares to prove her innocence.

Furthermore, while something like ‘vibhuti,’ the sacred ash made of burnt dried wood or burnt cow dung, is applied across the forehead only among devotees of Lord Shiva

— the destroyer of worlds and companion of Shakti — burning incense is also a common practice in Buddhism, Islam, and Christianity. Given that fire can eliminate filth and kill bacteria, it’s fitting that fire is seen as the remover of sin and revealer of truth.

So, Agni is a creator, destroyer, messenger, watcher, adjudicator, and purifier — but what does he have to do with Sita, Draupadi, and Kannagi? These women’s stories take place across the Indian subcontinent and across diferent times, yet Agni plays a crucial role in each one of them.

Sita in Ramayana

If you’ve ever celebrated Diwali — the festival of lights — with some Hindu friends, you probably have heard of the Ramayana

good fortune, wealth, and beauty. She’s also considered the daughter of Mother Earth, as she was found as a baby in a furrow that Janaka — the king of Mithila — was plowing, who then adopted and raised her as a princess. She married Rama, the prince and soon king of Ayodhya and the incarnation of Lord Vishnu, the maintainer of the worlds — thus her divine companion.

Agni crucially appears in the Ramayana afer Sita’s rescue and the crew’s return to Ayodhya. When they return, Rama hears concerns among his citizens about Sita’s chastity, and Sita willingly performs an agnipariksha to prove herself to the kingdom.

The epic, known in Sanskrit as “Rama’s journey,” centres around Rama and Sita: their upbringing, marriage, her abduction by the King of Lanka Ravana, Rama and his crew’s defeat of Ravana, and their return to the Kosala Kingdom’s capital, Ayodhya, where they are coronated as king and queen. The lamps lit by Hindus on Diwali symbolize the triumph of good over evil.

In the Ramayana, Sita is the incarnation of Lakshmi — the Hindu goddess of

The details behind the agnipariksha vary by the epic’s retellings across the Indian subcontinent. In one version, it is said Sita is being asked to prove herself to her citizens — but not Rama, as he knows her loyalty is on a cosmic level — primarily so that her husband can rule as a righteous and respected king. In another version, Rama also doubts her chastity, and Sita enters the burning pyre of her own accord to prove her faithfulness.

In a later addition to the original, Ravana is said to have abducted Maya Sita, an illusionary duplicate, while Sita was in the refuge of Agni. Through the agnipariksha, the real Sita switches with Maya Sita and returns. In this version, Rama is in on the plan while the citizens rejoice their queen is pure.

In yet another version, however, despite Sita being untouched by the fire, people continue to doubt, so Sita leaves for the forest. She returns years later with her and Rama’s grown-up sons, only to be asked to prove her chastity once more. Knowing that she’s done enough, Sita asks Mother Earth to open up and take her back — and Earth complies, swallowing her up whole.

Draupadi in Mahabharata

You may have heard of the Mahabharata through Oppenheimer’s famous misquote (“Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”) from the Bhagavad Gita — a scripture from the epic detailing a lengthy conversation between Krishna, another of Vishnu’s incarnations, and Arjuna, one of the five Pandava brothers central to the epic.

The Mahabharata, the Sanskrit roughly translating to “the great epic of the Bharata dynasty,” centres around the Pandava brothers: their growing up; exile by their cousins, the Kauravas; and the war between the Pandavas and Kauravas.

There are many reasons this war broke out, but chief among them is Draupadi. When Drupada, king of Panchala, performs a yajna

Feature — Trials by fre 22 The Varsity Magazine

asking for a weapon to destroy the Bharata dynasty — the Pandavas and Kauravas — Draupadi is born as a fully-formed young woman from the sacrificial fire. Through a series of intentional and unintentional acts by the many characters in the epic, Draupadi marries all five Pandava brothers, further setting the stage for the oncoming war.

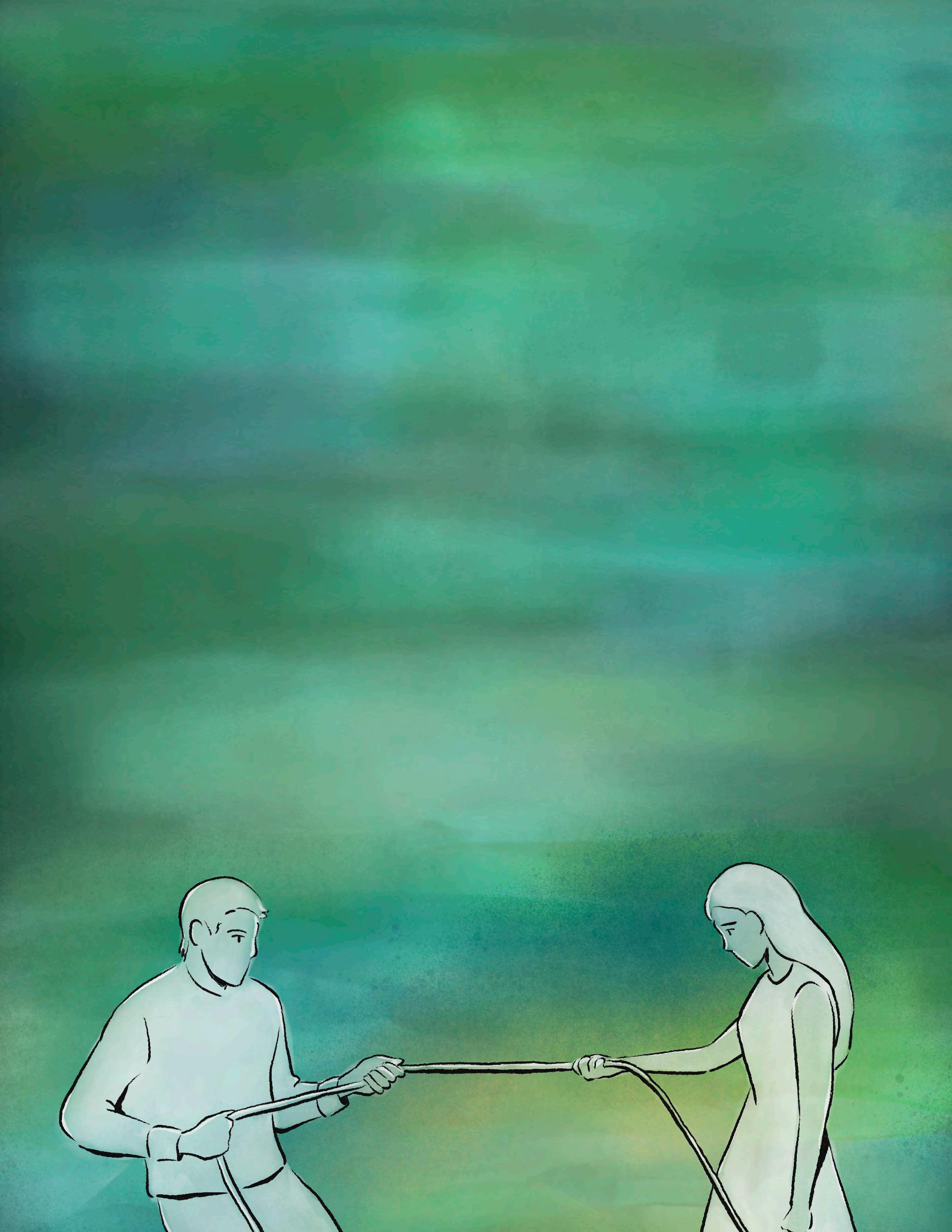

In all fairness, Draupadi herself didn’t intend to be a catalyst for the war. A pivotal moment in the war occurs when the eldest Pandava brother, Yudhishtir, bets his freedom in a slanted game of dice — and loses. When Saguni, the cunning maternal uncle of the Kauravas, reminds Yudhishtir that he still has Draupadi, Yudhishtir puts her at stake and loses her as well.

Draupadi is soon dragged by the hair into the court, and one of the Kauravas proposes that she is unchaste for being married to five men and orders that she be disrobed ‘like a prostitute.’ In the Mahabharata, this is considered incorrect because her role as a common wife is seen as a private afair; she was given a boon in a previous life to marry five Bharata princes, each begotten by a god; and more importantly, as she was born from fire and thereby a child of Agni, Draupadi is the epitome of purity. Narrative aside, there are other issues with this comparison: it should be obvious that sex workers should, regardless of what you think of their occupation, have basic respect and autonomy.

Thankfully, her disrobing is stopped by the powers above — but not quickly enough as her humiliation fuels her righteous anger that her husbands would have to act on. Each of the younger four brothers takes an oath of vengeance against the various people who took part in her humiliation, which they later fulfill during the war.

Kannagi in Silappathikaram

The Silappathikaram may not be a well-known Hindu epic, but it’s considered one of the five great epics of Tamil literature. Silappathikaram in Tamil roughly translates to “the story of the anklet.” The anklet in question belongs to Kannagi, who has a special place in my heart; my dad afectionately calls me his “Kannagi Amman,” as she’s considered my family’s kuladeivam — roughly meaning “family god,” similar to a guardian angel of sorts, in Tamil. My parents and their ancestors lived near and daily visited one of her temples in Sri Lanka, and so, though I am not religious, hearing the name fills me with pride and reverence for my roots.

The epic starts with Kannagi newly married to Kovalan, absolutely in love and bliss

in a flourishing seaport city in the Chola kingdom in what is now known as southern India. However, Kovalan meets and falls for a courtesan and dancer named Madhavi and moves in with her. Though Kannagi is heartbroken, she unwaveringly waits as a chaste woman for her unfaithful husband to return. Soon enough, a misunderstanding between Kovalan and Madhavi leads him to return to Kannagi, who takes him back despite the betrayal.

Afer having spent all his money on Madhavi, Kovalan is penniless — yet Kannagi encourages him to rebuild their life. They move to Madurai, the capital of the Pandya kingdom, where she gives him one of her jewelled anklets to sell. Then, in an unfortunate turn of events, Kovalan, framed by a merchant, is brought before the Pandya king whose queen’s anklets had been stolen and is immediately executed. Once she hears of this, Kannagi storms into the court and proves his innocence by breaking open her remaining jewelled anklet, revealing rubies instead of pearls. The king, mournful of his mistake, falls to the ground and dies suddenly, the queen soon following afer him.

Still, in a fit of rage and grief, Kannagi tears her breast of and flings it, cursing the city of Madurai. She demands Agni to burn the city, permitting only the good to escape: a large-scale trial by fire. And so Madurai is burnt to the ground.

truth, strength, justice, and purity — but for what? It is precisely their sufferings — the reasons for which I don’t know — that keep my mind preoccupied.

Of course, it is easy to dismiss their tragedies when one knows that parables are meant to convey a tale of good versus evil and that Hindu epics, in particular, are meant to demonstrate ‘dharma’ — one’s duty, or the right way of living — and ‘karma’ — the effects of one’s actions that determine their next life.

The point of this article isn’t to wedge feminism between people and their faith. I know that, in these tales, the characters are simply mirrors that writers, or the Gods, hold up to humanity, to show us the paths we could, and should, be taking and their consequences. After all, Sita is ultimately Goddess Lakshmi playing a role; Draupadi is never fully human, born already a grown

Placed on a pedestal, only to be burned down

By this point, you might be thinking: what the fuck?

These stories are tragic, the women undergoing severe hardship yet seemingly never achieving complete redemption. Sita, Draupadi, and Kannagi are epitomes of

Flame Winter 2024 23

woman from fire as a weapon of destruction; and Kannagi becomes memorialized as Kannagi Amman, her chastity and valour worshipped by many, including my family. The three women are the perfect wives, and thus exemplary of the perfect woman.

Yet, the tragic heroine is a constant archetype in stories, past and present, which only begs the question: why are women in stories persistently made to suffer? In the Abrahamic religions, all evil stems from Eve’s eating of the forbidden fruit. No such similar story exists in Hinduism to my knowledge.

According to Aristotle, a tragic hero must have a hamartia — a fatal flaw or error, not necessarily a morally condemnable one — that leads to their ill fate. While I consider Sita, Draupadi, and Kannagi to be infallible, do they also have a hamartia? Is Sita’s fatal flaw her excessive trust, ‘allowing’ her to be kidnapped; Draupadi’s her sharp tongue, which angered the Kauravas and invoked their hatred; and Kannagi’s her forgiveness? Or, are they not even allowed to be less than perfect?

I should mention that none of this is to say that the men in these stories don’t suffer. The men — Rama and Ravana, the Pandavas and Kauravas, Kovalan and the Pandya king, and more — do suffer, but they more or less suffer directly or indirectly by their own and each other’s actions. How I see it, the women in these stories suffer at the hands of men — men they trust will give them at least basic respect and keep them safe — for no fault of their own.

Now, one might think there’s merit to these women’s trials; they’re at least not docile or passive, instead choosing to venture alone into the forest; single-handedly raise children; wage war; or burn an entire city to crisps in righteous indignation — but it is still unfair that they had to be so strong in the first place. Though Sita might’ve been the only one to go through a literal trial by fire, Draupadi and Kannagi, too, go through their own metaphorical ones.

When I think about it, nearly every single woman I’ve adored and cherished in my life — and this probably extends to every woman in the history of humanity — has been prodded, questioned, and tested, their value apparently never inherent to themselves but given, and just as easily taken away, by others. As women, we’re placed on the highest pedestals, seen as precious vessels of purity, until just one blemish taints our surface — after which we’re burned down to ashes and a new pedestal is built for the next unsuspecting woman. Sooner or later,

we’re not young enough, naive enough, loyal enough, patient enough, or strong enough — good enough — for the patriarchy.

And having grown up religious, I can’t help but ask: what mistakes are okay? What is my supposed dharma, and is it different from that of men? Why is a woman’s chastity so important? Is my existence as a woman, marked by suffering according to one too many writers, karma for lives I don’t remember? Or are these stories simply highlighting the unfairness women endure from the men around them? Are these stories actually feminist?

When my mother lights the lamps and prays every morning at home — the place where seemingly only women are relegated to do so while men predominantly run the temples — should I join her? When I do join her, I watch the flickering flame and am reminded of Agni: in my story, does he play witness, protector, or male saviour? Or does he even care?

Often, I fear I am fated to end up like Sita, Draupadi, or Kannagi — my morality and intelligence tried, my body and self capitalized on without my will, or slowly made mad until I explode, incinerating everything I touch.

Alternatively, attaining perfection — impossible for any human but somehow made even more so for every woman — may just lead

me to give up entirely. It’s a more liberating prospect but still shameful with my conditioning. I have to remind myself: while I aim to embody Durga, I’m only mortal and I can’t triumph over evil all the time, so I’ll make mistakes, and that’s okay.

Do I hope that Agni, in some form, helps me walk through my trials of fire? Yes: as I’ve said my faith, or lack thereof, is the opposite of resolute.

But more so, do I hope that I can tame the flames, stoked by the women who came before me, fictional or real, so I can direct them to the patriarchy and set it alight? Absolutely.

24 The Varsity Magazine Feature — Trials by fre

Winter 2024 25 Flame

Illustrator: Mariia Charuta

The politics of Female Rage

Criticizing the feminized romanticization of suffering

The glamorization of women’s experiences is now dominating social media discussions. ‘Female Rage’ is one of these topics, with this title ofen coming alongside a film edit of clips glorifying ‘real rage’ — rage like a teenager slaughtering all of her classmates in Carrie or the famous “cool girl” monologue in Gone Girl

As I reflect on these videos, I can’t help but wonder: has this glorification of rage actively changed social perceptions of women’s anger? Has it saved the next generation of girls from their anger being weaponized against them?

I was born a girl, but I only became aware of the significance of this fact when I discovered it was a bad thing. Girl is a title of limitations which dictates the things I should not do: “Girls don’t talk like that,” “Girls don’t sit like that.” Growing up as a girl is learning all the things that come along with a “don’t.”

Girls are told to not be angry, that their anger is unproductive and irrational. As a child, I felt that I was distancing myself from the ‘ideal girl’ with every exertion of anger. When they say, “Calm down” and “Don’t be bossy,” I hear, “You’re not perfect, be better.”

What is anger? On a scientific level, anger is a primitive human emotion rooted in our brain’s reward circuit that is produced when we perceive an outcome that fails to meet our expectations. At its core, anger is a passion, a reaction to a perceived injustice.

I have been taught that a woman’s anger is an overreaction, a symptom of her period, or hysteria. Yet research such as Rebecca Nowlis’ 2000 study on the comparison of anger expression between men and women, women experience anger as ofen as men; they just process the emotion diferently.