9 minute read

Art

from 08202021 WEEKEND

by tribune242

NAGB’s conservation efforts for sister museums impacted by Dorian

TWO years ago, when the all-clear was given on September 3, 2019, hours after Hurricane Dorian had finally abandoned course in Grand Bahama, the National Art Gallery of the Bahamas (NAGB), was already hard at work responding to the needs of survivors and the general public.

Advertisement

Committed to putting the needs of the nation ahead of its own, the NAGB readily offered its facilities and networks to assist with relief efforts, providing a donation site and hosting fundraising events.

To particularly assist its three sister museums devastated by Dorian, the NAGB promptly coordinated conservation efforts for the Minnis Gallery in Marsh Harbour, the Wyannie Malone Museum in Elbow Cay and the Albert Lowe Museum in Green Turtle Cay.

NAGB’s former executive director, Amanda Coulson was able to get in touch with the Smithsonian’s Cultural Rescue Initiative (SCRI), a division of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, dedicated to helping American and international communities preserve their identities and history in the face of disaster.

Eager to lend its knowledge and expertise to the NAGB and the Antiquities, Monuments and Museum Corporation (AMMC), the SCRI scheduled site visits for late October 2019 to conduct initial assessments and make timely recommendations.

Between October 30 and November 1, 2019, a team made up of SCRI conservators, and NAGB and AMMC staff, toured the affected museums and historic sites.

One of the first stops was the Minnis Gallery in Marsh Harbour. Run by Roshanne Minnis-Eyma, daughter of Bahamian music and art icon Eddie Minnis, and her husband and fellow artist, Ritchie Eyma, the gallery was just beginning to grow its partnerships and expand its programming when Dorian hit.

Crouched in a bathtub for five hours with three others during the storm, Roshanne and Ritchie were certain all their paintings had been destroyed. But when their landlord sent word that the artwork was unscathed, the pair found themselves on the same flight to Marsh Harbour as the SCRI team who readily offered to assist.

The family’s original paintings, all 25 of them, had survived. While the gallery itself had sustained significant damage, the artwork “looked like it had just come from the framing shop”. As Roshanne explained, it was a combination of luck and preparation: “A few days before the storm, Ritchie decided to pack up all of the artwork and put them in bubble wrap and cardboard boxes in one section of the gallery. Surprisingly, all of the other doors (in the gallery) gave, but not that door.” The next stop on the SCRI’s art tour was the Wyannie Malone Museum in Elbow Cay. Opened in 1978, the museum quickly became a top attraction for visitors to Hope Town. Housing and exhibiting artefacts, documents, archives and other records that date back to the 1800s, the museum has spent the last 40 years preserving and honouring Abaco’s history and culture. In the aftermath of Dorian, the museum was faced with contaminated water tanks, a submerged fire safe and major damage to the floors and roof. As the museum’s only employee, Marjorie Chapman didn’t have the capacity to fix anything right away. The goal was simply to prevent further damage from occurring. In fact, by the time the NAGB and SCRI came some two months later, the museum was still “very much in its raw state”. Importantly, however, the knowledge and expertise they brought gave the museum hope.

The third and final gallery the SCRI team toured was the Albert Lowe Museum in Green Turtle Cay. Established by local artist Alton Lowe and named after his father, Albert Lowe, the museum has been a landmark in the cay’s historic district, New Plymouth, since 1976. The first historic museum in the Bahamas, it had acquired an extensive collection of antiques, artefacts, photographs and documents over the last five decades that brought to life hundreds of years of local and national history. Housed in a 150-year-old Loyalist home - one of the few structures to survive the 1932 Abaco hurricane - the Albert Lowe Museum is an architectural marvel. Constructed using traditional boat-building techniques, it sustained roof and water damage, but remained largely intact after the storm.

When the SCRI team arrived to assess the museum, they brought dehumidifiers and personal protective equipment to help volunteers safely strip the walls and salvage what was left. Thanks to Chris Dale, a second homeowner and close friend of the museum’s, 40 of Alton’s paintings had been

secured before the storm. But cardboard boxes were only a temporary fix. The paintings had to be removed and stacked in such a way that air would pass through, or else mould would set in. This basic yet critical conservation technique was the kind of information the affected museums needed access to, and the NAGB was resolved to get it. Everywhere the team went, they tried to leave behind as much information as possible, so that “any one of those institutions could help the community”. Recognising the impact of these efforts, a member of the NAGB’s curatorial team, Richardo Barrett, is now being trained to serve as an on-site conservator. To further assist the affected museums, the SCRI sent supplies and instructions on how to conserve the works to the NAGB this past November. The aim was for the museums to have everything in hand early last year, but when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, coordinating shipping from the SCRI’s headquarters in DC proved difficult. Given the pace of recovery efforts in Abaco, however, the delay went largely unnoticed. For the Wyannie Malone Museum, for example, the supplies are “very valuable…things that we will definitely need and are very glad to have,” but cannot be utilised until the building’s electrical and plumbing repairs are complete.” Sadly, the Minnis Gallery has fared much worse; it’s no closer to being opened than it was in the initial aftermath of the storm. While the space the Minnises had was cleaned up, according to THE MINNIS Gallery in Marsh Harbour, Abaco, before and after Hurricane Dorian hit. Ritchie, “it’s still a wreck ‘cause the owners (of the building) didn’t have insurance”. With no physical presence in Abaco, the family spent the latter part of last year revamping the gallery website in hopes of improving its online presence. Because Abaco was such a “beautiful, inspirational, motivational setting” for them as artists, Roshanne and Ritchie would love nothing more than to return to Marsh Harbour. The Albert Lowe Museum, like much of Green Turtle Cay, has made some progress. The museum’s furniture (circa 1860/1880) has to be replaced, but most of the rudimentary repairs are complete. As the museum continues to rebuild, Green Turtle native and museum liaison Leanne Russell believes there’s no better time to support and promote art education. To support the NAGB and its sister museums in Abaco, please visit: • https://nagb.org.bs/membership • https://albertlowemuseum.com/donate/ • https://www.hopetownmuseum.com/ support-the-museum. html To support the Minnis Family Gallery, please consider purchasing original works and/or prints from their website: https://octagon-glockenspieljc64.squarespace.com/

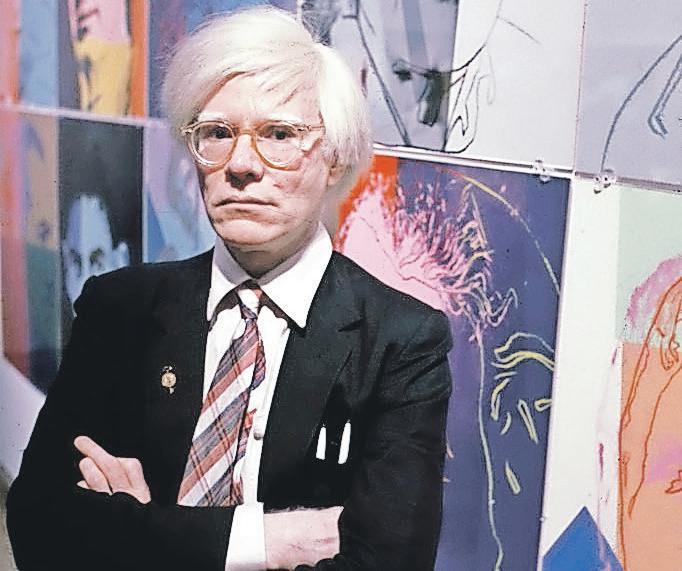

literary lives - Andy Warhol (1928-1987) The many facets of a pop culture

icon - Part II

Sir Christopher Ondaatje

continues to write about the American artist, film director, and producer who was a leading figure in the visual art movement known as pop art.

“We live in an age when the traditional great subjects – the human form, the landscape, even newer traditional subjects such as abstract expressionism – are daily devalued by commercial art.” - Andy Warhol

IN THE early 1960s, pop art was an experimental art form that several artists adopted: Roy Lichtenstein, followed by abstract expressionists William de Kooning, Jasper Johns, James Rosenquist and Robert Rauschenberg. Andy Warhol was known as the “Pope of Pop” and his first paintings were displayed in April 1961 as the backdrop for Bonwit Teller’s window display in New York. The gallerist Muriel Latow first came up with the idea of soup cans for Warhol. He wrote a cheque for $50 for the idea. A 1964 Large Campbell’s Soup Can was sold at Sothebys in 2007 to a South American collector for $7.4 million.

As his fame grew, Warhol hired several assistants to produce his silk-screen adaptations. He was fascinated by celebrities, painted them, and gradually developed his style, slowly eliminating the basic projection of his subjects on his final platform. He directed his assistants to make different versions and variations.

“Isn’t life a series of images that change as they repeat themselves?”

- Andy Warhol

Warhol produced both comic and serious works – a soup can or an electric chair. He used the same techniques whether he painted celebrities, everyday objects, or images of suicide or car crashes, as in the 1962 – 1967 Death and Disaster series. One of these paintings, the diptych Silver Car Crash became his highest priced work when it sold at Sothebys on November 13, 2013, for $105.4 million.

Warhol refused to explain his work: “All you need to know about the work is already there on the surface.”

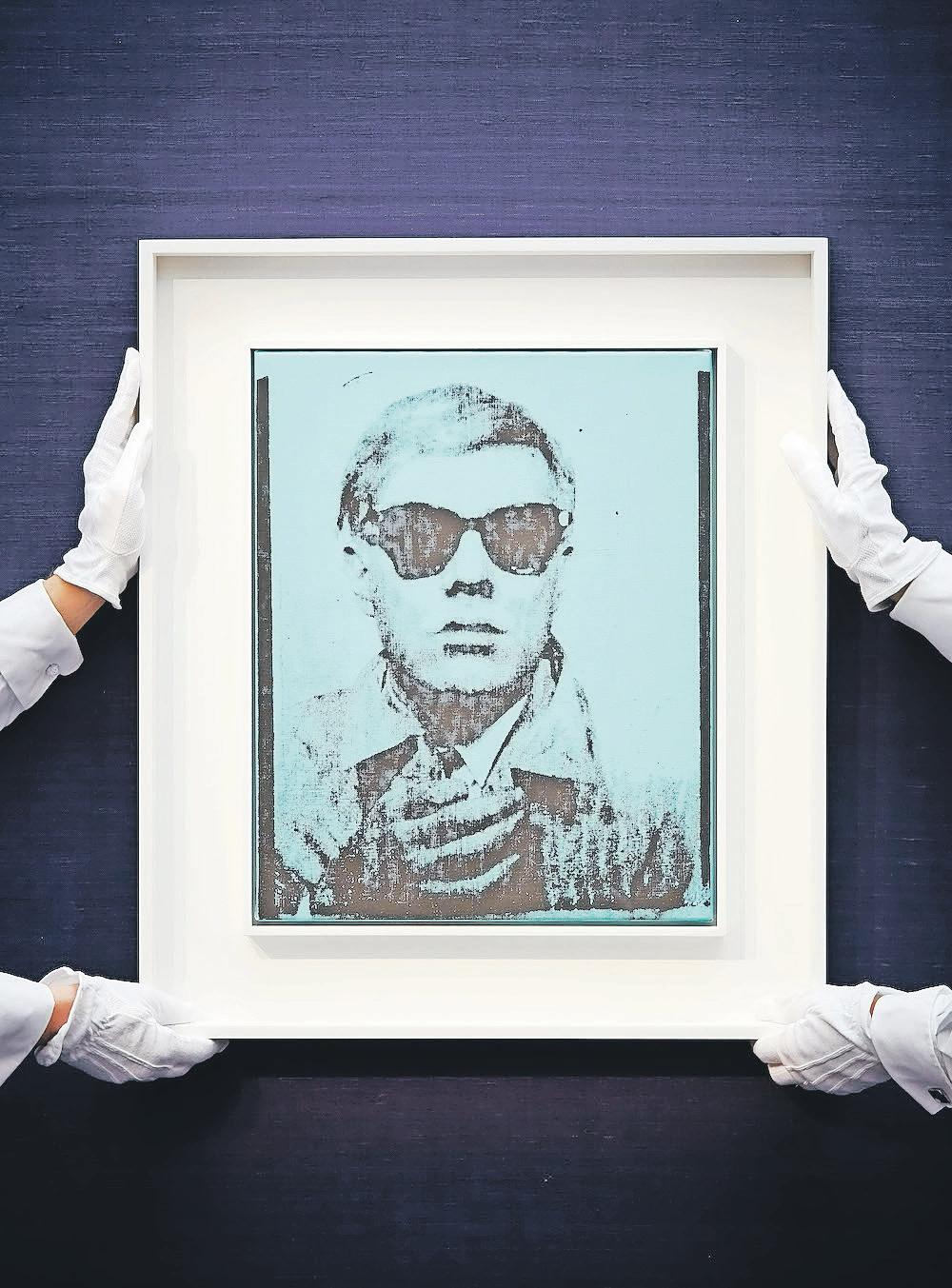

A self-portrait by Andy Warhol, done in 1963 – 1964, sold in New York at the May Post-War and Contemporary evening sale in Christies for $38.4 million. On May 9, 2012, his painting Double Elvis (Ferus Type) sold at auction at Sothebys in New York for $33 million. The painting (silkscreen and spray paint on canvas) shows Elvis in a gunslinger pose. It was first exhibited in 1963 at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles.

Warhol went on to make twenty-two versions of Double Elvis, nine of which are held in museums. In November 2014, Triple Elvis sold for $81.9 million at an auction in New York.

Between 1963 and 1968 Warhol made sixty films, as well as another five hundred short black-and-white “screentest” portraits of visitors to his studio, The Factory. He attended the 1962 premiere of the Statiz composition by Le Monte Young called Trio for Strings, following which he created his famous series of static films. Filmmaker Jonas Mekas, who accompanied Warhol to the Trio premiere, claims Warhol’s static films were directly inspired by the performance. One of his most famous films, Sleep, monitors poet John Giorno sleeping for six hours. Another film, Empire (1964), consists of eight hours of footage of the Empire State Building in New York City at dusk. His film Eat consists of a man eating a mushroom for forty-five minutes. Batman Dracula is a 1964 film that was produced and directed by Andy Warhol, without permission of DC Comics. It was only screened at his art exhibitions.

ANDY Warhol and, below, his first self-portrait (1963-4) sold at auction in New York for $38.4 million. Photo: Sothebys London

“It’s the movies that have really been running things in America ever since they were invented. They show you what to do, how to do it, when to do it, how to feel about it, and how to look how you feel about it.”