4 minute read

Creativity Defined

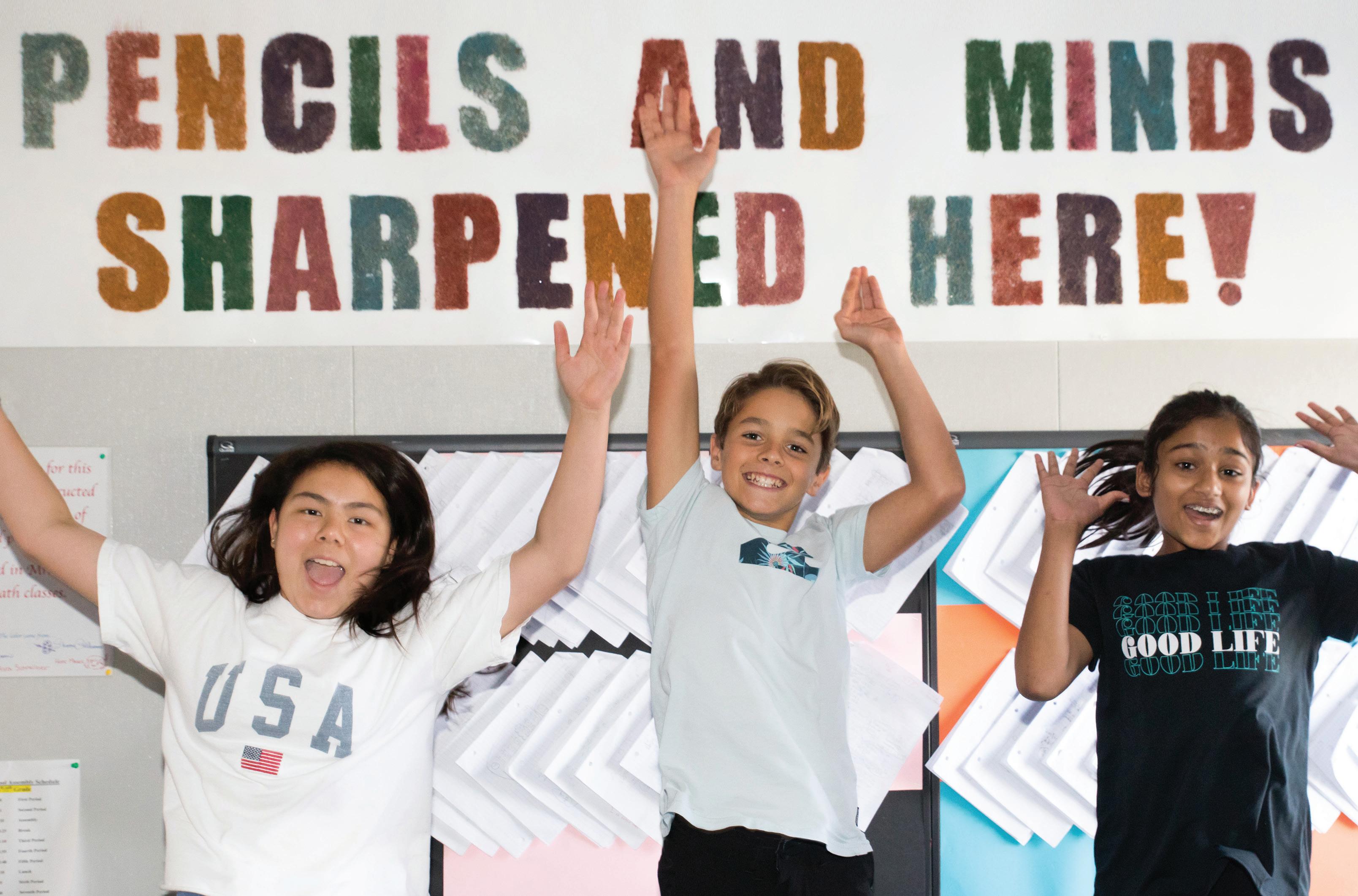

Upon entering my classroom, you will see a large sign that dominates the front wall and proclaims, “PENCILS AND MINDS SHARPENED HERE!” The sign is made from pencil shavings dyed in various colors and pressed into a thick layer of glue. Twenty years ago, I began collecting the pencil shavings from the electric sharpeners in my classroom. I had no idea what exactly I would do with this mathematical jetsam, but I knew there was an art project in there somewhere. The idea finally came from a dim memory of some first-grade Mother’s Day card made from glue and sparkles, and an almost equally ancient elementary science lab involving food coloring.

When was the last time you were creative? I don’t mean the last time you made a unique series of menu choices on an app, or when you searched for an idea on the internet. When was the last time you encountered a problem that you had no idea how to solve…and then you solved it anyway? Where did the

Advertisement

Devin Seifer

solution come from? How did it feel?

Creativity is really hard to define and even harder to teach. To put your mind at ease, you should know that in researching this article, I carefully analyzed all 1.2 billion hits from a Google search for “creativity definition.”

In many ways, our technological society is less geared for promoting creativity in children than it used to be. With almost instant and effortless access to information and the ideas of others, students rarely have the opportunity to spend minutes, hours or even days pondering a problem. In addition, many students have much of their “non-school” time taken up by video games, social media and adult-structured activities. Without much opportunity for free-play, where is the time for just thinking? It has, therefore, become more important than ever for teachers to encourage students to think for themselves, take intellectual risks, and make creative and productive mistakes in the search for understanding.

My definition of creativity comes in two parts: the “what” and the “how.” The “what” is that creativity is the ability to shuffle, bend, stretch, and recombine all the things that you know in an effort to solve a problem in a new way. The “how” is going to take a bit longer to explain. I believe that there are three brain mechanisms at work in creativity. The first is a massive, chaotic sea of information consisting of facts, beliefs, ideas, and experiences. This sea is constantly churning, warping and re-linking everything that you know into new combinations and arrangements. The vast majority of these new combinations are unworkable, unhelpful, or just plain ridiculous. The second brain mechanism is a subconscious link to a conscious effort at problem-solving. Possible problems could range from “How am I going to decorate the living room?” to “How can I get along better with a friend?” to “How can I design an experiment to disprove the existence of dark matter?”

The subconscious link sifts through the sea of recombining information, discarding most of what it finds in search of new ideas that just might have a chance to work. When a potentially interesting idea is pulled out of the muck, the conscious brain takes over (mechanism number three) and tries to forge the idea into an actual solution that can be put into effect.

Here, therefore, is the sentence that justifies putting you through the previous paragraph. Since creativity starts with recombining information that already exists in your brain, you cannot be creative unless you actually know stuff!

It is not enough that you know where to find information; the information must already be inside you. So the answer to the dreaded question, “Why do we have to learn this?” is that the more knowledge you acquire, the more raw materials you have to fuel your creativity. And this is true even if you are firmly convinced that the odds of your ever using the knowledge in its pure form are extremely low. We claim to place a high value on “out of the box” thinking, but how are people supposed to learn how to think outside of the box if they allow a box do all of their thinking for them?

I wish I could tell you that I had a recipe for teaching creativity in our tech-dominated society. I don’t. The best we can do is to provide opportunities for students to develop it on their own. We also try to model it for our students with how we design teaching materials. If I had another 882 words to play with, I would list some of the many ways that we do these things at Pegasus. In the interests of space, however, I encourage you to ask your child’s teacher(s) to provide some examples. I’m sure that they would be happy to do some bragging.

By the way, I still have about five gallons of pencil shavings sitting in a cabinet just waiting to be transformed into a new mathematical art project. If you have any creative ideas, then let me know. Devin Seifer has guided about 1,400 Pegasus middle school students through the perils of algebra and pre-algebra over the last 20+ years. Most survived. Contact: dseifer@thepegasusschool.org We claim to place a high value on “out of the box” thinking, but how are people supposed to learn how to think outside of the box if they allow a box do all of their thinking for them?