10 minute read

Reopening Forman During a Pandemic

them to be a better reader, writer, or mathematician, but that they taught them to be a better person. Our new national remote learning experience can teach us a lot about the value of schools beyond just the intended.

Great teaching is a matter of context

Over the past few decades, an incredible amount of time, energy, and money has been spent on identifying the most effective teaching practices. University-based researchers spend hours upon hours in classrooms identifying what seems to work well. They distill these experiences into routines and strategies that can be replicated in countless classrooms. They test these practices in the most scientific ways possible to hopefully confirm the validity of using one approach over another. The objective of these researchers is to help provide alternatives and inform us about what will really make a difference in student lives and learning. The pandemic threw a wrench in these works, though. As we all scrambled to move to remote learning, we attempted to repurpose these best practices for a new technological setting. We quickly identified that some worked better than others. In fact, some of these practices were a complete failure in this new setting. The reasons were obvious. The researchers assumed students would be physically in a classroom, that school operated in a synchronous fashion with all students in the same time zone, that the teacher could move around the classroom to check understanding, facilitate students working in groups, monitor assessments for individual accountability, and craft an experience in real time and space. The research was based upon a conception of school that was very different from the one we are all currently experiencing. The pandemic highlighted that teaching is equal parts art and science. Science helps us better understand the “how” of teaching while art gets at the “why” of teaching. With the change in context, good teachers knew they would need to rely more on the art of teaching. I do not think any teacher felt like an immediate success, but the more fruitful ones took what they knew from the science of teaching (how students learn best) and focused on the why of learning. They did not try to recreate the classroom setting in a virtual world. They critically examined many of the assumptions about schooling and out of this created something new, something that challenged many of these assumptions. It is this challenging of assumptions I find most interesting. I do not want to just return to the way things were before. This pandemic has taught us a lot about what we value and miss from the time before the virus, but it has also allowed us to imagine ways that things might also be different. It has taught us that great teachers are not bound by assumptions and can learn to thrive in different contexts.

Ritual and routine are undervalued

As I travelled around the campus this fall, I would often hear new students ask older students if an experience they were having was normal or just a “COVID-19 thing.” More times than not, the student would reply that it was a “COVID-19 thing.” The response of “COVID-19 thing” tended to have negative connotations. It meant that things were better in the past, but that we needed to put up with this strange way of doing things to be back on campus. We needed to abandon many of the things that were

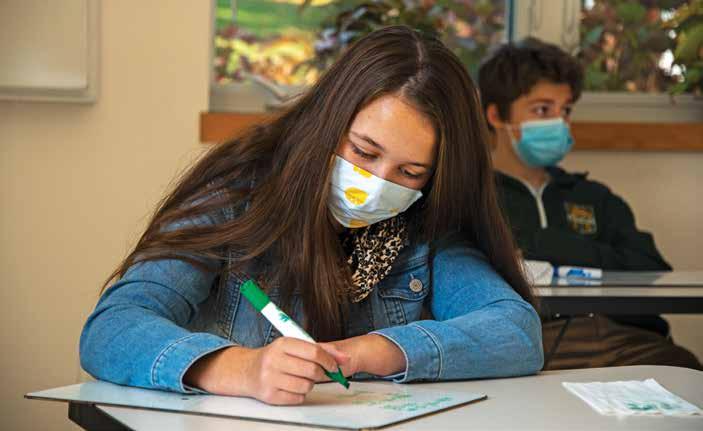

Students gather for a photo outside the Science Center.

part of our common experience. Oftentimes these were things we took for granted. Some were obvious: no athletic competitions, no walks into town, no assemblies.

These changes were painful to the community. My heart broke watching teams practice day after day knowing they would never actually get to play a different team. I struggled to tell my advisees “No” when they pleaded to just be able to walk into town. They promised not to enter any stores or stop to talk with anyone; they just wanted to know there was life outside our campus. We knew these changes would be hard and put a strain on our community. What we did not fully predict were how many little things would need to change and how big an impact this would have on our community. Things like all being able sit down together for community meals; cheering from the sidelines with a fellow group of students and teachers; having students be able to visit a friend in a different dormitory; taking your advisees for coffee in town; greeting all the students with a hello and a handshake in the morning; and so many other little rituals and routines that make up a typical day at Forman. Just to be able to bump into someone walking across the campus and talk without worrying if your mask is on properly and you are more than six feet apart took on real value. A community is not built just out of goodwill and a common purpose. It is the often-overlooked rituals and routines that make communities work effectively and create bonds among the members. Take, for example, communal meals. I can hear the groans of students as they file in for Monday community lunch. Assigned to sit with a group of students they do not know, and with a faculty member that does not teach them, the conversation will likely be strained. It would be far easier for everyone to just sit with their friends and colleagues, but this small act builds connections across grades and social groups. It subtly develops a sense of comradery and breaks down barriers. This is impossible to do with partitions on tables and half the student body taking their lunch for grab and go. On its own, this ritual is not that significant, but taken in total with all the other changes, it hinders the development of a strong community. This is true not just at Forman, but at schools across the country. I think this has been the hardest thing about the pandemic — our inability to connect in the ways to which we are accustomed.

Perseverance

As I look back out the window and wonder how much snow will actually accumulate, I notice a dark shape along the perimeter of where the tents once stood. It is already turning dark but I can make out that it is a fox. I wonder, with its nose to the ground, if it is on the hunt or just looking for a discarded crust of pizza left behind when the Bistro stood there. The fox is probably happy for the quiet that has returned to campus, but I find I already miss the noise. I do not miss the worry that each day might be the day — the day when a COVID-19 case turns up on campus and turns this experiment in learning upside down. The day when the complaining about what has changed at Forman turns to real worry about illness and safety.

One final lesson learned is that people have a remarkable ability to persevere. That even though things were dramatically different, and not what we planned or hoped for, students and teachers came together and did the right things. It has been, and will continue to be, a challenge, but one that is worth the struggle.

Adam K. Man P’15 Head of School

Students with learning differences are not ideal candidates for a fully remote educational experience. Therefore, in the late summer of 2020, the challenge for Forman was to open the School for in-person learning while maintaining a safe, virus-free community.

Opening Forman School in the late summer of 2020 was an unprecedented undertaking. Everything about welcoming students back for another year had to be viewed through the lens of COVID-19 and keeping everyone healthy.

“Once we had figured out the move to remote learning in March, we immediately began to consider how we would open back up in August,” says Head of School Adam K. Man P’15. “Finishing one school year under unusual circumstances while preparing for opening the School in a brand new way was daunting. Many people worked extremely hard to make it happen.”

Due to the fast-paced nature of change regarding how to best manage the campus regarding COVID-19, Forman had to have strong plans in place but also be willing to make changes as new information and thinking developed.

“It helped that we had a big group in place,” says Ashley Banks, Director of Health Services. “We were meeting regularly and sharing the latest information from a variety

of sources, not just the CDC or the Department of Health. Things were changing a lot regarding recommendations for testing and monitoring. It was a lot to keep track of but we were a real team.”

There were many revisions to the original opening plan and Banks was grateful that Man had an open mind and was willing to change course, based on the latest and best information available. The School was also vigilant about communicating plans, and changes to plans, to students, faculty, staff, and parents. Keeping everyone aware of expectations was instrumental in making sure everyone was pulling in the same direction, toward the healthiest campus possible.

An important part of Forman’s overall approach was its COVID-19 status flag system, which ranged from Red (campus lockdown) to Green (schoolwide restrictions lifted but masks still required). Early on, it became clear that Forman could likely keep the campus safe but could not really control what was going on in the outside world. Traveling into Litchfield, a regular student activity, could not realistically happen without enormous effort. Visitors to campus were very limited, sometimes to only a contactless drop off of items at tables in front of Henderson. These conditions were hard for some but were clearly in the best interest of the entire community.

“I felt for the kids,” says Man. “Their lives were very restricted. I sought to alleviate that whenever I safely could. We never went below Orange status but, on campus, we had elements of Yellow a few times. We merged some dorms regarding activities, we opened the gym and fitness center with group size limits in place, with masks of course. But we never got to the point where we could let them go home for the weekend. It wouldn’t have worked.”

Forman School made it to November 20, the day students departed for Thanksgiving, without a single COVID-19 case on campus since the day students returned. Banks says there were many factors but the most important was the School’s commitment to testing, specifically surveillance testing. Banks and her team were testing about 10% of the campus each week and the number went up to 20% by the third week of November.

“We contracted with a good lab and our team worked well with them,” says Banks. “We did the testing ourselves which allowed for quick turnaround as we didn’t have to book an outside firm each time I wanted to test a dorm. We always had a strong handle on the health of the campus because the School made the financial commitment to such regular testing. I don’t know of another school that tested as often as we did.”

Forman used PCR tests, the gold standard for COVID-19. The advantage of regular surveillance testing is that, without it, you don’t know if someone is infected until they display symptoms and they could have been spreading the disease between infection and the appearance of symptoms.