6 minute read

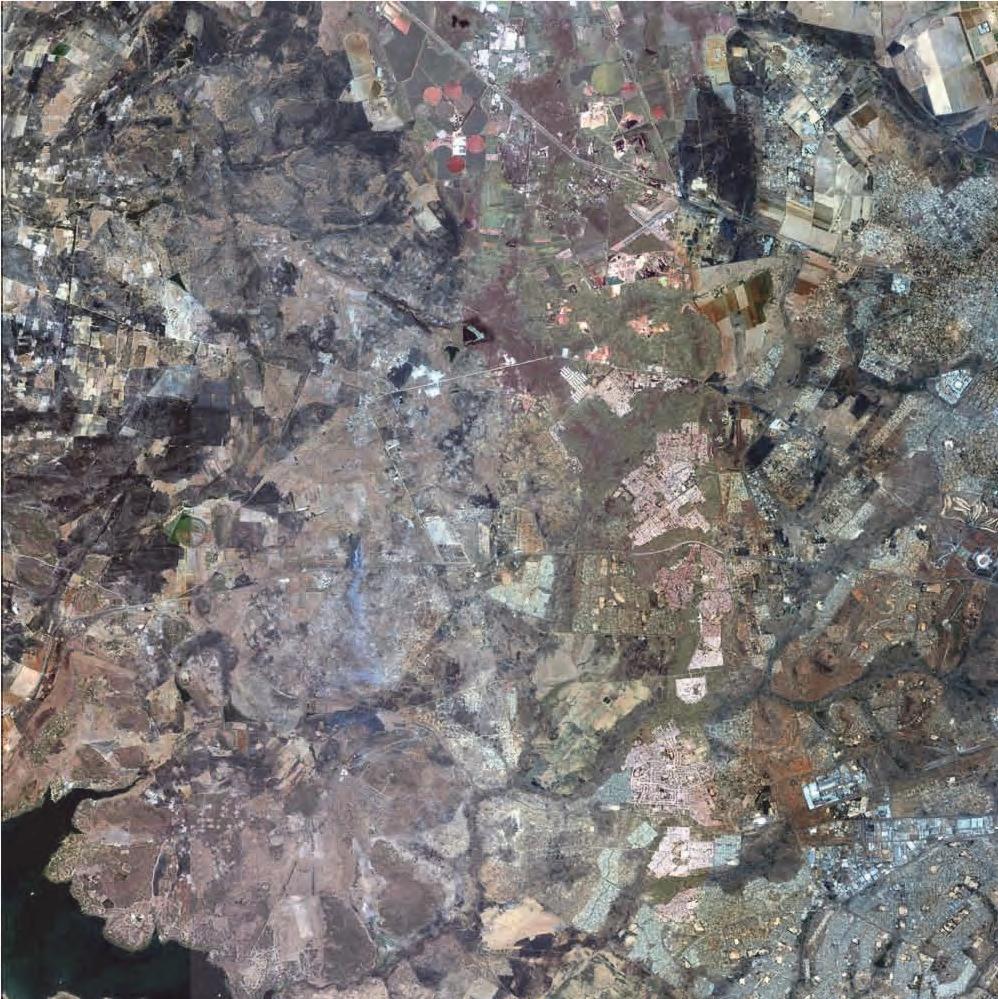

THINKING OF HARARE 2040 & HARARE 2014

Planning For The Medium And Long Term Without Forgetting The Immediate Needs

Written by Carlos Cubillos

Advertisement

The work of our Planning and Urban Design group within Gensler as a global architecture, design and planning firm, takes us to many varied locations in the globe. We are constantly addressing challenges and opportunities posed by projects located in different climatic, geographic and cultural conditions. We work in the freezing tundra (Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation), in the humid and hot tropics (Malaysia, Singapore, Latin America), in arid desert locations (Middle East and North Africa), etc. As we learn from each unique location and project, we have come to believe that in this urban age, where the population living in urban areas far exceeds that of rural ones, cities are the scenarios where answers to humanity’s future ought to be found. As Jaime Lerner, former mayor of Curitiba in Brazil, rightly points out, cities should not be seen a problem but as the solution to contemporary life.

Ever since the presence of paths and rivers led to people meeting each other and exchanging goods and ideas, the physical conglomeration resulting from those exchanges created places where human beings tried to find satisfaction of basic needs and access to goods and services. Cities became the places where ambitions, aspirations and other material and immaterial aspects of life could be realized. Nevertheless, the prospects of prosperity and individual and collective well-being are constantly compromised by multiple causes and the prosperity generated by cities has not been equitably shared, leaving a sizeable proportion of the urban population without access to the benefits that cities can produce.

In our work we have found the need to think of cities as platforms that can generate and equitably distribute the benefits and opportunities associated with prosperity, ensuring economic well being, social cohesion, environmental and life quality, and we have become firm believers in the need to think of the future of our cities using a holistic, multi-disciplinary approach. The future of our cities is not the sole domain of the politician, or the engineer, or the architect, or the landscape architect, or the planner, or the sociologist, or the economist, or the investor; all should be active part in the planning and construction of this future. We, as well as many other actors dealing with cities in this urban age, refer to this framework as “Sustainable Urbanism”, where we plan for people-centered places, capable of integrating the tangible and intangible aspects of prosperity, and shedding the inefficient, unsustainable forms and functionalities of the city of the previous century.

The lessons extracted from the work we do around the globe, lead us to believe that sustainable urbanism is a topic of global interest that should be based on an understanding of local circumstances, otherwise it runs the risk of being irrelevant. Sustainable developments must respond to and improve cultural, social, geographic, climatic, and environmental aspects, without overlooking economic sustainability and governance. Underlining the need to understand the specificities of every location, we have found common principles that contribute to the creation of a sustainable urbanism:

1. Promoting compact and denser developments, reducing our cities’ urban footprint and inducing walking and bicycling.

2. Inducing behavior change, educating the population and increasing general awareness about our cities and environments of which they are part of.

3. Mixing compatible uses, where housing, work, education and recreational functions may be located within reachable distances.

4. Increasing connectivity by considering intermodal public transit, linked to density and land uses.

5. Proposing uses and operations that are socially and economically viable.

6. Controlling air, water, noise and visual contamination.

7. Reducing, reusing and recycling solid waste, which may require a reorganization of public services, and educating the population in regards to its benefits.

8. Fostering sustainable life cycles, where opportunities for increased autonomy in the production of food, energy and water are considered.

9. Stimulating knowledge, innovation, job creation and social interaction.

10. Preventing natural disasters, including the capacity to mitigate risks. This involves showing respect for the territory and reconnecting to the history and culture of the place where the city seat is.

11. Considering sustainable infrastructure and architectural strategies.

12. Looking towards a better future, while learning from the mistakes and successes from the past and present.

13. Developing programs of immediate and short-term application tied to a mid- and long-term vision. They should respond to pressing needs that cannot wait for a later response.

Visiting Harare for the first time meant setting foot in a place that reminded me of my native Colombia. This, and the chance to connect with the new generation that is being educated at my alma mater of past years, sparked a lot of “dot connecting” moments. The Gensler / Penn Harare studio has been a window to reframe the knowledge and experience acquired in the planning work we do at Gensler, and to filter it through the realities of developing nations, toned with opportunities, challenges and permanent contradictions, while building visions of a brighter future for current and future generations. I strongly relate to this.

The intellectual and creative capital of Penn students and professors, stimulated by the thoughts of invited critics, Zimbabwean colleagues, officials and citizens that have been active part of the Gensler / Penn Harare studio, is compiled in this publication. It sets compelling, fresh and ingenious planning seeds that seek to achieve a more inclusive and prosperous future for the capital of Zimbabwe. Some may reflect ideas that could be implemented in the short term while some may require longer planning horizons. All should be enriched and fine-tuned with the added input and participation of local authorities, stakeholders and communities.

Planning by definition deals with the future, and to put ideas into reality considerable time is sometimes needed, running contrary to the pressing needs of the population and the short term political life span of local administrations, desperate to find innovative and relevant ideas that could see the light of day in as short a timeline as possible. As an interesting precedent already shared in that memorable first week in Harare at the start of 2013, I would like to mention the potential relevance of some of the events that I witnessed and was a part of when I was living in Bogota, Colombia, before joining Gensler. It was providential that an unprecedented trio of well prepared and innovative mayors occupied office consecutively, each building upon the strengths and legacy of his predecessor. Jaime Castro put city finances back in health; Antanas Mockus engaged in educational and cultural campaigns, fostering pacific behaviors and increasing civic awareness and tolerance; Enrique Peñalosa focused on transportation, open space and education as a backbone to increase equality and inclusion. Peñalosa understood the need to have a city wide vision for years to come, but also engaged in a set of key strategic actions to be implemented during his three years in office, promoting a city model giving priority to children and public spaces and restricting private car use, building hundreds of kilometers of sidewalks (where cars were not allowed to park), bicycle paths, pedestrian streets, greenways, and parks. He led efforts to improve Bogotá’s marginal neighborhoods through citizen involvement; understanding the added value of good design he engaged local architects to design parks, libraries -in buildings and on wheels-, and schools to be run by the private sector; planted more than 100,000 trees; created Transmilenio, a highly successful bus rapid transit system; and turned a deteriorated downtown avenue into a dynamic pedestrian public space. He helped transform the city’s attitude from one of negative hopelessness to one of pride and hope, believing in the need for high quality and welldesigned physical environments to develop a model for urban improvement based on the equal rights of all people to transportation, education, and public spaces.

The Penn students’ proposals for Harare think of the city as a place for individual expression but also for collective action, while focusing only in one part of the city, due to practical and time constraints. Hopefully, subsequent studios will focus on other parts of the urban area and the region in general, and start to consolidate an overall framework tying planning and design ideas together. The outcome of the Gensler / Penn studio shows some of the inventiveness and simplicity of ideas set forth in Bogota and in other cities in emerging economies, which like Harare, are in a constant quest for a more balanced, sustainable and inclusive future for its citizens, including innovative yet simple ideas. These Penn proposals address perceived opportunities to enhance the public realm, create physical environments that provide citizens much needed access to high quality amenities and services, and consolidate rights to the ‘commons’ for all as a way to expand prosperity and inclusion under an umbrella of sustainable urbanism. They represent an opportunity for Harare to openly ask questions about what it wants to be, make decisions, and implement actions that could become urban seeds to spark prosperity. These projects are an opportunity to build a shared and enduring vision for Harare that could serve as a guide for the current and future administrations and the population they serve.