2 minute read

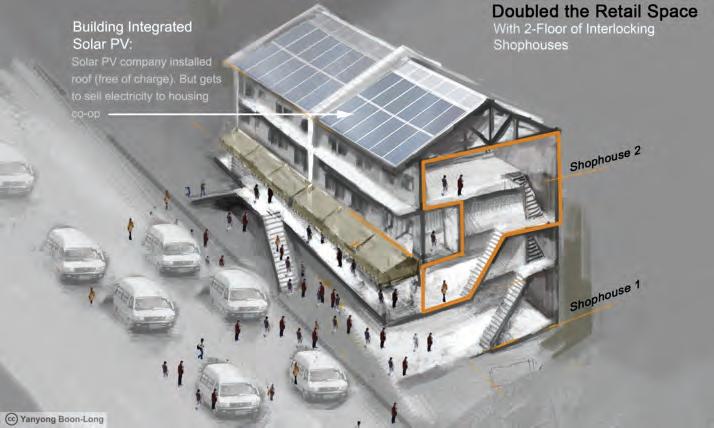

INTERLOCKING SHOPHOUSE

Advertisement

Written by Yanyong Boon-Long

According to the City of Harare Planning Department, each day over 1 million migrant merchants pour into the city to sell goods. In a discussion about the potentials of the city, Mr. Psychology Chiwanga, head of City Planning stated “Harare supports the non-tax-paying population that commutes into the city on a daily basis. The city’s infrastructure cannot sustain itself this way.” This phenomenon is not unique to Harare. The majority of major metropolitan areas around the globe experience a large influx of migrant labor or commuters on a daily basis. They inhabit the city during the day and return to their residences in the evening, which are sometimes as far as 2 or 3 hours away. This puts immense pressure on the center, which should ideally be solved through different measures including densification of housing within close proximity. The interlocking shophouse is one such solution. It provides an opportunity to densify an area while increasing economic activity.

In late 19th century America, immigrant communities were known to make use of different variations of this concept. They combined residential and commercial activity as a way to increase their household income. This could be considered an early prototype of the shophouse. Although this was limited to immigrant communities and did not infiltrate mainstream society, the benefits were felt throughout society. The same occurence can be seen in Thailand, where the house is often viewed as an instrument for making a living. “Baan Ni Yu Laew Ruey,” which means, “this house will make you rich,” is a typical saying in Bangkok when migrant workers move into their new houses in the city. Their houses provide shelter, but are also expected to act as income generators. Frequently, these migrants start off as street sellers in the city. Upon accumulating enough customers, they open a shophouse so they can, in turn, store more products and gain more customers. The cycle continues, eventually leading to the development of entire communities.

During our tours of Harare and interviews of the residents, we discovered that a successful street seller can earn up to $2,000 per month while a potato seller in Mbare can earn $20 a day on a good day. City officials explained that the salaries of most formal sector employees average about $150 per month. So it seems that despite the drop in large-scale agricultural production, small-scale independent farmers can be fairly successful.

The immediate problem facing these independent traders is the lack of housing and affordable commercial spaces. The city faces the challenge of finding a way to formalize these businesses. A shophouse is a building typology that could provide a stable foothold for micro-entrepreneurs in the urban core, while allowing the city to benefit from the income they generate. The combination of commercial and living space would require mix-used zoning for live-work. The benefits, including the creation of sustainable communities and generating income for the city would far outweigh any perceived costs.

GREATER HARARE DENSITY

TRAFFIC CONGESTION

Industrial Areas

DISTRIBUTION

WETLANDS

DRAINAGE