Black Drum

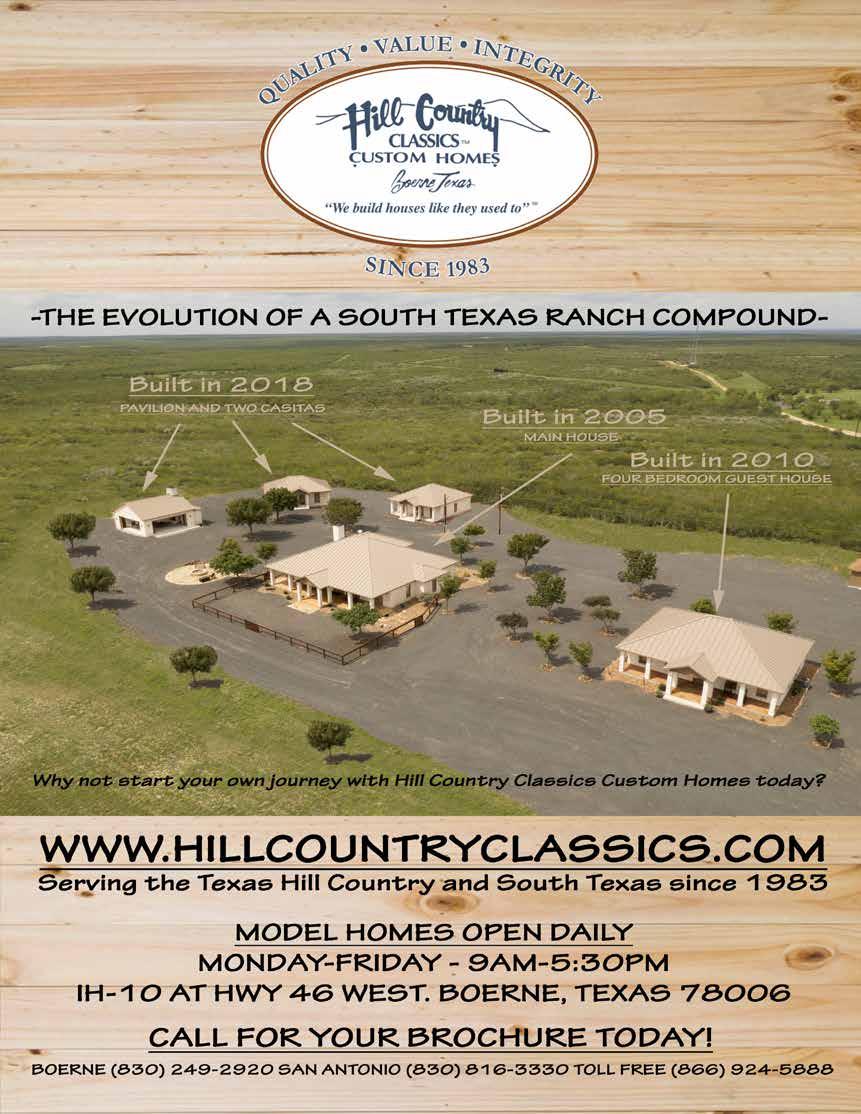

First, I want to thank you for the privilege of being the next president of the Texas Wildlife Association. I was first introduced to TWA by Kirby Brown in 2010. While I have always strongly believed in conservation, hunting, and land stewardship, TWA and its mission were new to me. I quickly became very involved in TWA and soon became a director, followed by being invited to join the Executive Committee.

It has been a great experience and I look forward to working with you to further the mission of TWA: serving Texas wildlife and its habitat, while protecting property rights, hunting heritage, and the conservation efforts of those who value and steward wildlife resources.

Allow me to introduce myself. I live in Kerr County where I manage and operate Cherry Creek Ranch with my family. The ranch runs a cow/calf and lease hunting operation. In addition to ranching, I am a county commissioner in Kerr County and own a retail nursery and landscape company. I am married to Karen and have two sons, Sam and Gus.

TWA is in a great place today. We have new headquarters in New Braunfels that, if you have not yet visited, I encourage you to do so. Our outstanding staff led by Justin Dreibelbis would love to show you around as we continue to focus on our core programs of Conservation Legacy, Hunting Heritage, and Advocacy.

All of this would not have been possible without the incredible dedication and work of the Texas Wildlife Association Foundation. These TWAF trustees raise the funds that enable Conservation Legacy and Hunting Heritage to reach the hundreds of thousands of children and adults whose lives have been touched by these programs.

On a recent trip, Steve Lewis asked me what my goals as TWA president are. His question has caused me to reflect on this over the past months. Several answers are simple. I would like to expand the reach of our programs, expand membership, and maintain our financial strength. These are all important, but I think there is an even more important fundamental task. I can sum it up in a word—community.

TWA is a family of local communities. I, and all of us, must continue to engage the local communities around the state in their local TWA events and organization. Whether it’s a junior high field day in Brenham, a big game banquet in Fredericksburg, opening your ranch for a TYHP hunt in Brady, or a Boots on the Ground legislative event in Austin, I need you to be involved.

Our staff at headquarters and around the state help coordinate these events and I will try to attend as many as possible. But you are the key ingredient. If we can accomplish this, our programs, membership, and financial strength will take care of themselves.

TWA is truly a family and I am excited and honored to be here for its next chapter. Please feel free to contact me at any time for any reason and I look forward to meeting you soon.

Serving Texas wildlife and its habitat, while protecting property rights, hunting heritage, and the conservation efforts of those who value and steward wildlife resources.

28

Ph.D.32

34 Exploring the Carbon Sequestration

Potential of Texas Oyster Reefs

by KELLEY SAVAGE, M.S., NATASHA BREAUX, M.S. and JENNIFER BESERES POLLACK, Ph.D

by JOSEPH RICHARDS

by WILL LESCHPER

by SALLIE LEWIS SCHNEIDER

by KELLEY SAVAGE, M.S., NATASHA BREAUX, M.S. and JENNIFER BESERES POLLACK, Ph.D

by JOSEPH RICHARDS

by WILL LESCHPER

by SALLIE LEWIS SCHNEIDER

Once considered a trash fish by many coastal anglers, the black drum’s reputation has risen considerably of late. Coastal anglers value them as hard fighting, great tasting additions to a day on the water. Biologists focus on them because, as an indicator species, the fish reflect the overall health of estuarine ecosystems, as Nate Skinner reports in his article beginning on page 8.

AUGUST 4-6

Adult Learn to Hunt Program

Huntmaster, Volunteer Training, TBD. Contact Matt Hughes mhughes@texas-wildlife.org

AUGUST 8

Member Happy Hour, Corpus Christi. Contact Kristin Parma at kparma@texas-wildlife.org for more information.

AUGUST 16-18

Statewide Quail Symposium, Abilene

AUGUST 19

Adult Learn to Hunt Program

Tamalada, TWA headquarters. Contact Kristin Parma at kparma@texas-wildlife.org for more information.

AUGUST 31

Member Happy Hour, Nacogdoches. For information, contact Matt Hughes at mhughes@texas-wildlife.org

FOR INFORMATION ON HUNTING SEASONS, call the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department at (800) 792-1112, consult the 2022-2023 Texas Parks and Wildlife Outdoor Annual, or visit the TPWD website at tpwd.state.tx.us.

OCTOBER 5

James Green Wildlife & Conservation Initiative

Fundraising Event, Fort Worth. For more information, contact tjgoodpasture@texas-wildlife.org or www.twafoundation.org

OCTOBER 10

Texas Outdoorsman Of The Year, San Antonio. For information, contact tjgoodpasture@texas-wildlife.org

OCTOBER 20-21

Panhandle Wildlife Conference, Lubbock. For more information, contact Kristin Parma, kparma@ texas-wildlife.org

DECEMBER 11

7th Annual Houston Clay Shoot, Greater Houston Gun Club. Contact Kristin Parma at kparma@texas-wildlife.org for more information.

TWA’s Conservation Legacy team will conduct six Teacher Workshops this spring and summer. The workshops are 6-hour trainings that introduce attendees to TWA, in-class and outdoor lessons and activities, and how to incorporate natural resources into classrooms or programming. Lessons focus on teaching land stewardship, native wildlife, and water conservation and are Science TEKS-aligned for Grades K-8.

• Designed for Grade K-8 educators

• Open to all statewide formal and informal educators. The workshops are not restricted to a certain district or region.

• Workshops are offered at no cost

• Six, 6-hour workshops offer CPE credit

• Provides hands-on training for educators to incorporate natural resource and private land stewardship lessons into their teachings.

For more information, go to www.texas-wildlife.org/ educator-development-and-resources

Black drum often congregate around jetties and other structures, offering a quality angling experience for all ages and all levels of experience.

In recent years, black drum have become increasingly popular among recreational coastal anglers and coastal biologists alike. The angling crowd values the sporting fight they provide on light tackle and their tasty contribution to the table. Fisheries biologists focus on them because they, as an indicator species, reflect the overall health of estuarine

ecosystems. They have also alleviated some of the angling pressure on other highly targeted fish species.

BLACK DRUM BIOLOGY

According to TPWD biologists, the black drum is a member of the croaker family and is related to the Atlantic croaker, red

drum, and spotted seatrout. One distinguishable characteristic that this family of fish possess is the croaking or drumming sounds it makes with its air bladder. Hence the common names croaker and drum.

The drumming sound is most developed in the black drum, and anglers can sometimes hear sounds from schools of the fish passing under their boats. The drumming noise is regularly heard when adult fish are brought aboard a boat.

Smaller sized black drum are often referred to as puppy drum or butterfly drum. Fish more than 30 pounds are called bull drum or big uglies and the large specimens can be either male or female.

Some of the most notable black drum landings each year take place during the annual “black drum run” in early spring. This is when large drum gather in schools before spawning in many areas of deeper bays, in and around jetties, the Gulf, and in passes and channels. Many Texas coastal anglers anticipate the black drum run each year, as it likely provides the best chance to land a fish weighing 30-40 pounds or more.

Black drum spawn in either bay or Gulf waters as well as in the connecting passes. Free spawning, or the random release of eggs, occurs mostly in February, March, and April, with some later spawning in June and July. Larval black drum can be

found in the surf and along bay shorelines as early as March and April. By early summer, 0.5- to 1-inch juvenile black drum are common in shallow creeks, sloughs, and harbors.

Young black drum feed on marine worms, small shrimp and crabs, and small fish. Larger, mature drum eat small crabs, worms, algae, small fish, and mollusks.

Black drum use their barbels, or whiskers, to find food by feel and smell. They often dig or root out buried mollusks and worms while feeding in a head-down position along the bottom. This feeding process is called tailing because the fish’s tail can often be seen protruding above the water’s surface when they are searching for food in shallow water.

Black drum can adapt to a wider range of habitats than any other notable fish species swimming in Texas bays. They can be found in clear water over sand flats and in the muddiest waters of a flooding slough. Black drum can thrive in water so shallow that their backs are exposed, as well as in Gulf waters that are more than 100 feet deep.

They are found along the extremely warm, shallow flats of the Laguna Madre during the summer and survive better than many other fish in freezing temperatures. Black drum are attracted to the freshwater runoff from creeks and rivers, yet can also live in waters twice as salty as the Gulf of Mexico. This adaptability arguably makes the black drum available to more anglers than any other bay fish.

The annual harvest of black drum along the Texas coast is usually more than 1.3 million pounds by the commercial fishery, and approximately 750,000 pounds by recreational anglers. Many anglers maintain that black drum weighing less than 5 pounds that are cleaned and prepared properly may taste

better than other highly sought-after fish. A plethora of coastal restaurants noted for their seafood up and down the Texas coast serve black drum extensively.

According to the TPWD Upper Laguna Madre Ecosystem Leader Ethan Getz, the black drum population has remained steady coast-wide for several decades.

“Catch rates have been especially high in Baffin Bay, despite periods of hyper-salinity, water quality issues, and occasional freeze events,” Getz said. “Our creel surveys show an increasing trend in harvests for black drum along the entire Texas coastline in recent years by recreational anglers. It’s safe to say that more and more anglers are turning their attention to black drum.”

Getz said the fish in Baffin Bay tend take on a little bit different pattern during their spawning season compared with black drum in other bay systems.

“Because the black drum that reside in Baffin Bay do not have access to any nearby passes leading to the Gulf, they will instead run up into creeks to spawn,” Getz said. “In fact, we see commercial fishermen taking advantage of this behavior quite a bit during their spawning season, or the spring drum run. A good portion of commercial harvests during that time of the year come from creeks that connect to the estuary.”

Getz said the adaptability of black drum to withstand a wide range of salinities, water temperatures, and conditions has strongly contributed to the sustainability of their populations along the Texas Gulf Coast.

“Our estuaries undergo extreme swings in salinity regimes from time to time, depending on how wet or dry the conditions are,” Getz said. “There are times when some of our bays become almost completely fresh due to immense runoff from major pre-

cipitation events, and then there are occasions where salinities climb to levels higher than that of the Gulf. Regardless of where salinity levels are, black drum populations continue to thrive.”

Getz said studies show that when salinities become extremely high, the movements made by black drum decrease significantly.

“They may change their behavior some, but they can seemingly tolerate just about any water conditions that they are faced with,” Getz said.

Studies have shown that black drum exhibit some interesting characteristics in terms of their genetics and the waters that they inhabit.

“Black drum are genetically distinct in the western Gulf of Mexico, compared to the Eastern Gulf and the Atlantic Ocean,” Getz said. “Furthermore, black drum in Baffin Bay and the upper Laguna Madre show a different genetic structure from other populations in Texas.”

This is likely due to unique life history characteristics. “For example, black drum in Baffin Bay spawn in Baffin, separate from other populations, which tend to make runs near Gulf passes.”

According to Getz, black drum in Baffin Bay also reach maturity earlier, at 2-3 years of age, compared with other populations where they do not reach maturity until they are 4-5 years old.

“This may be an adaptation to the intense periods of hypersalinity that they endure in Baffin Bay,” Getz said.

TPWD Aransas Bay Ecosystem Leader Zachary Olsen said that black drum are capable of living a long time for fish.

“Studies indicate that there are records of fish that have lived to be over 50 years old,” Olsen said. “They are just a really long living, hardy fish that have been able to take advantage of just about everything that Texas estuaries have to offer.”

Olsen said that one important characteristic about black drum that makes them a key species is that they can be caught by a wide variety of anglers with varying skill levels and water access.

“You don’t have to own an expensive bay boat or high dollar equipment to successfully catch black drum,” Olsen said. “There are plenty of land-based and shore-bound anglers, or bank fishermen, who catch a lot of black drum every year. The species really gives everyone an opportunity to tangle with them.”

Black drum grow fairly quickly, and can grow to 11-12 inches long in two years.

“Fish that are two to four years old may measure anywhere from about 12-17 inches,” Olsen said. “At least half of these fish have reach maturity at this age and size, and that’s why we have the minimum bag limit for black drum set at 14 inches.”

According to Olsen, the population of black drum along the Upper Laguna Madre and Baffin Bay is about four to six times the size of populations found in any other bay system.

“This is a direct result of the fact that black drum in the upper Laguna Madre and Baffin Bay mature at a very young

age,” Olsen said. “The fish in this area also have extremely large recruitment events. These events tend to follow periods of extreme conditions. They seem to have really successful recruitment during years following freezes or periods of super high salinities.”

About two years ago, the Aransas Bay complex experienced one of the highest recruitment periods for black drum that it has seen in many years, according to bag, seine, and gill net surveys. Olsen said that TPWD is seeing the evidence of this from the different age classes of fish that are now present in the ecosystem.

“We saw an immense increase in the amount of juvenile black drum that were present in the Aransas Bay system a couple of years ago, and now we are encountering a ton of one- to twoyear-old fish in our gill net surveys,” Olsen said. “This means that successful recruitment is taking place, and the future for black drum looks bright.”

Natasha Breaux, research staff member and project manager at the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies, has been studying the black drum’s prey in Baffin Bay. Tissue samples taken from black drum can indicate what the fish has been consuming, which will ultimately reveal whether the fish spent the majority of its life in the Laguna Madre versus Baffin Bay.

“The Laguna Madre has a lot of seagrass that black drum use for feeding grounds,” Breaux said. “Tissue samples from fish that have been feeding along the seagrass flats in the Laguna Madre give off a much different isotope signature compared to the tissue from fish that have been feeding along the serpulid reefs of Baffin Bay, where they are generally consuming mulinia clams.”

Breaux said that some of her research has shown that when salinities are extremely high, black drum within Baffin Bay tend to migrate into the Laguna Madre less frequently, preferring to confine themselves to the waters of Baffin proper.

“What makes this behavior somewhat of a conundrum is that the main food source for black drum in Baffin, which are mulinia clams, become more scarce during periods of extremely high salinities,” Breaux said. “We are assuming this behavior of more limited movement by these populations of drum within Baffin Bay under elevated salinities is due to osmotic stress, but we don’t really know for sure.”

Over the years, this behavior from black drum to resist migrating out of Baffin Bay when high salinities occur has seemingly caused some fish populations to have poor or deteriorating body compositions. There has not been any notable documented die-offs within these populations, leading researchers to believe that the fish may be malnourished due to their shear massive numbers and a reduction in food availability when these events have occurred. This, again, speaks to the incredible size of the population of black drum that inhabit Baffin Bay.

The popularity of black drum among recreational anglers and inshore sport fishermen seems to have increased significantly over the last decade. According to Olsen, noteworthy increases in recreational harvests as indicated by TPWD creel surveys began to take place back around 2012.

Bank and pier fishermen, along with those who are simply fishing for anything that is willing to eat whatever bait that they have hooked to the end of their lines, have been enthusiastically targeting and catching black drum for a long time. However, this has not been the case for the angling crowd whose affinity for sport fishing.

Anglers obsessed with the challenge of targeting specific species like speckled trout, redfish, and flounder have historically considered black drum a trash fish or bycatch. Until recent years, these folks were not purposely targeting black drum, and those who limited themselves to chunking artificial lures rarely caught them.

According to Senior Executive Director of the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies Dr. Greg Stunz, there has been a major shift in the inshore sport fishery toward black drum.

“More and more anglers have fallen in love with the sport of chasing black drum,” Stunz said. “Folks realized that they are great to eat, and that they can be caught using a variety of tactics that can be both sporting and challenging, not to mention a whole lot of fun.

Fly anglers are targeting black drum, and those using conventional tackle are sight casting to them on the flats. The species is definitely ranking right up there with speckled trout, redfish, and flounder, nowadays.”

Stunz said that the increased popularity for black drum among anglers is having a positive impact on Texas coastal fisheries.

“It’s helping to alleviate the pressure on other species and motivating anglers to practice catch and release in situations that they previously might not have done so,” Stunz said. “With black drum populations so high, it makes sense for anglers to keep some for the dinner table, while hopefully releasing some other fish.”

Angler numbers continue to soar, as the pressure on fisheries grows every year. “Catch and release is ultimately going to be the only solution for maintaining the robust fisheries that we have on the Texas coast, and I believe black drum can help with that.”

Long time Rockport area fishing guide Capt. Jay Nichols said that black drum seem to be becoming more of a highly soughtafter species for anglers each year.

“Black drum definitely play a major role in the fishing guide business along the Coastal Bend,” Nichols said. “I have many clients that contact me specifically to chase black drum. The species has become a mainstay during the summer months along the flats, and we regularly sight cast to schools of them. Black drum are exciting and fun to catch, and they can produce lifelong on-the-water memories for anglers of all ages and experiences.”

Corpus Christi fishing guide Capt. Jesse Torres said that black drum are an important species for him and his clients on the Laguna Madre and Baffin Bay.

“A lot of anglers have realized how sporting it can be to chase black drum, as well as how good they are to eat,” Torres said. “As a fishing guide, it’s nice to have another species to be able to target with my clients, besides speckled trout and redfish. And our waters are chock full of black drum during the summer and fall, which ultimately makes my job a little bit easier.”

Torres said the sight casting opportunities that schools of black drum provide on the Laguna Madre and Baffin Bay have really become a game changer.

“Sight fishing is something that all anglers should experience,” Torres said. “It’s exciting and challenging, and our black drum populations give anglers the opportunity to try their hand at it, almost anytime they are on the water.”

The black drum has seemingly become the catalyst of diversification across Texas coastal fisheries. Immense populations of the species provide anglers with plentiful opportunities to enjoy rod-bending action in a variety of locations, using a plethora of tactics.

While the black drum’s contribution as table fare is great, its significance to our estuaries is even greater. The fish will no doubt play an important role in the future of our bays for many years to come.

Many TYHP volunteers are also hunter education instructors. Not only are they active hunter education instructors, TYHP volunteers account for XX of the Hall of Fame Hunter Education Instructors.

If you have attended a TYHP hunt, you have likely seen a wildlife biologist or a game warden. We do this as part of the education on a hunt. We believe seeing wildlife professionals can spark young people’s interest in a field they had not considered or weren’t even aware of.

Did you know many game wardens and wildlife biologists are also Huntmasters who run hunts? Below we are highlighting some TPWD partners who volunteer for TYHP. Obviously, in a

The Texas Youth Hunting Program (TYHP) logo includes the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s (TPWD) simple but very recognizable green square. The “small in number but large in impact” TYHP staff are regularly mistaken as TPWD employees. In many ways we are— and we don’t mind the error.

Of course, our parent organization is the Texas Wildlife Association. It can be confusing. Just ask the TWA receptionist who answers calls many times a day from people with wildlife questions and problems. TWA and its education, advocacy, and appreciation programs are proud partners with TPWD. In fact, TYHP had its beginnings in the Wildlife Division at TPWD. Ours is a strong partnership. The ongoing link between TPWD and TYHP is hunter education. We like to say our youth hunters get to put into practice what they learn in the classroom.

short article, we cannot mention them all, but we want to highlight the commitment of our partners to TYHP’s mission.

Steve Hall, TPWD hunter education director, has been a Huntmaster since 1998 when he taught the first Huntmaster training and developed the first Huntmaster manual. Steve is a fixture at the Cave Creek Wildlife Management Association Super Hunt, which celebrated its 20th season in the 2022-2023 season.

When asked why he got involved in this endeavor, he said, “Professionally because it is the best answer to the five factors that create a lifelong hunter. They are providing education, providing equipment where necessary, providing mentorship, providing a threshold experience, and providing access to a place to hunt.” In Steve’s assessment, TYHP provides all this and TWA was the natural home because of its connection to so many private landowners.

John Apgar is a game warden in far West Texas and a mentor among game wardens and wildlife professionals. He has made it his personal mission to get more young people involved in hunting because he has seen the numbers of people hunting decline over the years. He has been a Huntmaster since 2010.

Not only do Agpar and his team offer some of the most exciting and challenging hunts, but the education and outdoor experience is unbeatable. Team Apgar is made up of a number of TPWD professionals. Since they represent this partnership and the future of this program, thanks go to team members Olivia Grey, Benny Benavidez, and Jose Etchart.

While we are saying thanks, Wade Anders and Jamie Hamilton deserve mention; they are not TPWD employees, but passionate TYHP volunteers. Hamilton wanted better equipment for the hunters on the hunt and made a generous donation to make it happen. With Anders’ help, the hunters in West Texas have some of the best rifle set-ups to take those long shots and do it effectively and ethically.

Retirement has not changed Albert Flores’ commitment to TYHP. Flores, who retired as a game warden in 2019, still serves as a Huntmaster on the Weld-

er Wildlife Refuge. Like Apgar, Flores encouraged his fellow game wardens to get involved. If you go on a Welder hunt you will likely see Game Wardens Lerrin Johnson or Kevin Mitchell as part of the hunt’s education.

Some of the TPWD biologist young guns in the Wildlife Division are also making a splash including Austin Stolte, Chase McCrory, Gaby Tamez and James Weaver. They are all lead Huntmasters who run excellent hunts for young people in West Texas.

The example these professionals have set has encouraged new TPWD employees to get involved, like Amanda Young, Ian Witt and Megan Granger. Ian and Megan are two of the newest Huntmasters, having attended Huntmaster Training in September 2022 in Comfort, Texas.

Technical Guidance Biologist Joyce Moore has been a fixture at TYHP Super Hunts. She has taught a lot of young people and parents about whitetails and wildlife management in general over

the years. James Rice, superintendent at the Albert & Bessie (ABK) State Natural Area, is responsible for opening more state properties to TWA and TYHP. His interest in making headway on deer management has resulted in many years of hunts on ABK.

Game wardens and biologist are not the only ones leading hunts. Immanuel Salas, an avid bowhunter, runs a new archery hunt for us at Lake Georgetown on Army Corps of Engineers property. Renan Zambrano has run hunts in Brown County for five years. We would be remiss if we did not mention Carter Smith, former TPWD executive director, who not only has been a champion of TWA and TYHP but set the example by hosting a TYHP hunt on Dobbs Run, his family ranch, for many years.

The partnership is strong and growing stronger every day because of those who are willing to give a most precious commodity—time.

The Student Land, Water & Wildlife Expedition (LWWE) program is a conservation partnership between Texas Wildlife Association and school campuses. LWWE supports middle and high school science teachers by providing classroom natural resource TEKS-aligned lessons that culminate with a day-long outdoor expedition experience to enhance student comprehension of land, water, and wildlife stewardship as part of their formal science studies.

Partnering science teachers participate in a one-day workshop in summer or fall where they choose four complimentary formal lessons to incorporate into their yearlong curriculum. TWA educators meet monthly with these educators to facilitate the lesson implementations and informal assessments. In the spring, the

entire grade level participates in a full-day expedition on private land often hosted by TWA members. Natural resource partners in the area volunteer their time and expertise by presenting on either land, water, or wildlife topics during multiple station rotations.

Brenham Junior High School: 7th grade – 385 students

Compass Rose Journey Middle School (San Antonio): 6th & 7th grades – 120 students

Fort Worth Country Day: 7th grade – 87 students

Medlin Middle School: 7th grade – 330 students

San Antonio Academy: 7th grade – 23 students

“It was a wonderful experience for the boys and us staff. Thank you!”

San Antonio Academy Science Teacher

“Providing our students an opportunity to go onto a private ranch and being able to facilitate science lessons aligned to land, water, and wildlife.”

Compass Rose Journey Middle School Assistant Principal

“The kids really enjoyed the water station that Ms. Yvonne facilitated. It was super engaging and students learned so much about the water cycle during her lesson.”

Compass Rose Journey Middle School Assistant Principal

“Loved how organized they (resource materials) were, how everything was laid out ready for you. Lessons and fieldtrip, Nearpod quizzes.”

Medlin Middle School Science Teacher

“The labs were a great resource to add into our curriculum.”

Brenham Junior High Science Teacher

“They loved the drones because of the technology.”

Brenham Junior High Science Teacher

“I love that there are so many hands-on and active experiences for students and that the presenters are so passionate about their topics.”

Fort Worth Country Day Science Teacher

LAND STATIONS – STUDENT TESTIMONY

“My favorite part was the drones because I liked the way he explained everything. I also like drones a lot.”

“I think my favorite part of the expedition was when we’d move stations and we’d walk through all the grasses and downhill and around the lake, it was cool seeing how big the land was.”

WATER STATIONS – STUDENT TESTIMONY

“I genuinely enjoyed the stream trailer and catching bugs to identify them.”

“My favorite part was being able to see what we do every day can affect the environment.”

WILDLIFE STATIONS – STUDENT TESTIMONY

“I think it was fun overall and not much I would change. If I could though, I would have more time at each station, especially the CSI quail station. It was really fun.”

Official Corporate Conservation Partner of TWA

FOR YOUR CONTINUED SUPPORT!

“My favorite part was when we played the Predator Prey Game.”

My name is Karly Bridges and I joined the TWA team as the Conservation Legacy program assistant. I am beyond excited to help bring education and fun into classrooms all around Texas through our Discovery Trunks.

I am from Santa Fe, Texas, and have lived in New Braunfels for about 10 years. I have a bachelor’s degree in Animal Science and a passion for wildlife conservation. I have been hunting and fishing “since I was in diapers” as my dad says. So conserving wildlife and its surroundings has been thoroughly instilled in me.

Whether it is harvesting animals knowledgeably or just doing our part to conserve habitats, our wildlife and natural resources need our constant consideration. Educating the future generations is very exciting and I can’t wait to dive in!

I have two awesome kiddos with my husband of eight years. If we aren’t outside working on projects around our property, then we are most likely having dance parties in the living room. We soak up all that nature has to offer by hunting around the Hill Country or fishing on the Coast. Our favorite place to visit, multiple times a year, is Port Aransas. You just can’t beat the atmosphere there.

I am a huge LSU fan and enjoy most every sport, but football is king in our house. I value family more than anything and truly enjoy being with mine.

I hope to play a part in many individuals’ processes of realizing how much the outdoors has to offer and inspiring them to never take it for granted.

Jared Schlottman Conservation Education Specialist

Howdy, my name is Jared Schlottman and I am pleased to serve as a conservation education specialist for the Texas Wildlife Association. In this role I will collaborate with TWA partners to engage adults across the state through innovative natural resource management programs.

I am originally from Round Rock, Texas, but spent much of my early life exploring the lands and waters of the Hill Country. I was introduced to hunting, fishing, hiking, and otherwise exploring the outdoors at an early age, which helped me gain an appreciation for wildlife and fisheries conservation very quickly.

Soon this appreciation for our shared natural resources found me pursuing an undergraduate and master’s degree in Wildlife and Fisheries Science from Texas A&M University. During my time at A&M, I worked for the Natural Resource Institute in several different roles, including student intern and graduate researcher. My master’s research involved translocating bobwhite quail to evaluate the feasibility of population restoration.

One of my great passions is educating others, especially when it comes to teaching about private land stewardship, wildlife habitat management, or other natural resource related topics. I look forward to building new relationships that help protect our shared natural resources and move the needle of wildlife management in Texas.

Article by ADDIE SMITH and AMANDA ANDERSON Illustrations courtesy of NRI

Article by ADDIE SMITH and AMANDA ANDERSON Illustrations courtesy of NRI

Scientists employ various methods, models, and data to track weather patterns, including drought—a condition closely monitored by Texans, especially those involved in agriculture and natural resources. You might be familiar with the U.S. Drought Monitor (USDM), often referenced by meteorologists to show the severity and location of drought. A broad network of experts update the USDM using the best available data and local knowledge.

During a weather report, meteorologists often show cloud cover from satellite images, especially during hurricane season

and periods of heavy rainfall. Satellites are also used to detect and monitor drought.

One example is NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) satellite. Images collected with this satellite help scientists create the Vegetation Drought Response Index (VegDRI), an indicator of vegetation stress due to drought. Made available weekly to the public through the USGS Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, VegDRI integrates remote sensing, climate, and biophysical data to provide timely drought information for the U.S.

The satellite can “see” parts of the light spectrum beyond what is visible to humans. This means it can help measure how vigorously plants are growing or how stressed plants are based

on the amount of light absorbed or reflected at certain light wavelengths involved in plants converting sunlight to energy. Who would have thought photosynthesis and satellites working together could produce incredibly insightful data? Science!

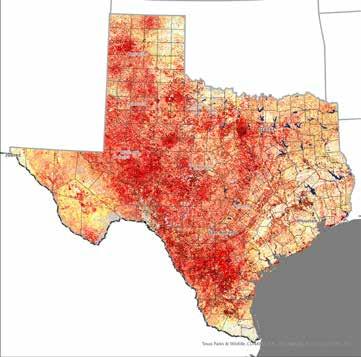

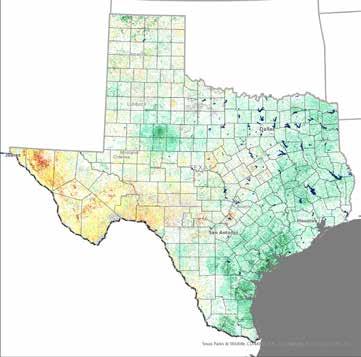

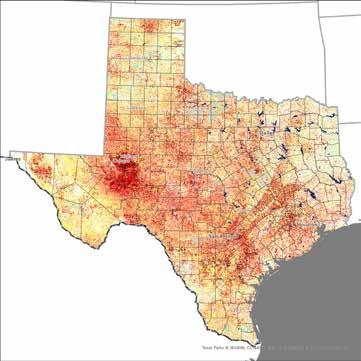

Let’s take a look. The first set of maps above are taken from VegDRI across a series of dates showing change in drought over a year from August 1, 2021 to July 31, 2022. Note that the darkest green represents extreme moisture, and the white represents near-normal conditions.

In August 2021, drought was almost non-existent in Texas, but by August 2022, almost all of Texas was impacted by some level of drought. Looking at the next two maps, we see that rainfall in August 2022 provided relief by September 2022, but without sustained rainfall, drought increased again by the end of September 2022.

• August 3, 2021—Approximately 14,000 square miles or 5 percent of Texas was in any drought category (D0-D4), affecting approximately 135,000 people, less than 1 percent of the state’s population.

• August 2, 2022—Approximately 263,000 square miles or 99 percent of Texas was in any drought category (D0-D4), affecting approximately 28,752,000 people, 96 percent of the state’s population. Of those, 72 percent of the population experienced “extreme” and “exceptional” drought (categories D3-D4).

• September 6, 2022—Approximately 20,066,500 people or 67 percent of the state’s population were affected

by drought (D0-D4). Of those, 11 percent experienced “extreme” and “exceptional” drought (categories D3-D4).

• September 27, 2022—Approximately 21,264,500 people or 71 percent of the state’s population were affected by drought (D0-D4). Of those, 11 percent experienced “extreme” and “exceptional” drought (categories D3-D4).

Of the 18 native species and three introduced species of birch found within the lower 48 states, river birch is the only specie found within Texas. River birch, Betula nigra , is most often found in the Piney Woods vegetational region but is also common in the Post Oak Savannah. Its appearances are rarer in the eastern Blackland Prairie and the Gulf Prairies and Marshes.

This is a tree of the state’s eastern quarter where rainfall is abundant most years and creeks and rivers are plentiful. It grows into a tree 20 to 30 feet high with a broad, spreading crown, but it can reach as tall as 90 feet. As its name implies, river birch is found growing on the edges of wetlands and on banks of creeks, rivers, and ponds.

Its wetland indicator status is facultative wetland, meaning that 66 to 99 percent of the time it will be found growing adjacent to water. This tree can tolerate wet roots growing in saturated soils of creek banks or wetlands. To look for river birch on your property or hiking area, look in the wetter areas and on creek banks.

This native tree’s bark is very conspicuous with a cinnamonred to reddish-brown color on young trees, with mature trees showing light gray to silver bark. The bark will peel away in papery-thin layers much like wood shavings, but these layers remain on the tree, giving it a shaggy look. On younger trees,

the peeling layers reveal a salmon-pink bark underneath; older trees reveal a grayish silver bark below.

Leaves are simple, alternate, and roughly triangular to ovate, margins doubletoothed, thick, and leathery, 1 to 2 inches wide and 2 to 3 inches long, shiny dark green above and paler with short, matted hairs underneath. Petioles are slender with matted hairs and up to ½-inch in length. Male and female flowers on the same tree produce separate catkins. The flowering period is March to April. Fruits are cylinder-shaped cones, about 1-inch long, with scales covering small winged nutlets produced from May to June.

The leaves and twigs of river birch provide fair to good quality browse for goats and deer that is occasionally used by cattle. Game and songbirds eat the seeds. When growing near the banks of rivers and creeks, river birch roots are valued for erosion protection.

Grazing management on the wooded sites where river birch grows is important to maintain survival and growth of seedling birch trees. If mature river birch is present, then seedling to young-age trees should be growing on the site. If few or no seedlings are seen, then livestock deferment of these wetland/riparian areas will allow seedlings to become established.

If stocking rates are reduced or withheld for two growing seasons, you will be astonished at the numbers of several woody plants that have produced seedlings. These new, tender seedlings were

being produced each year but were being browsed by livestock and wildlife. Many times, if there is a source of seeds or hard mast from a diversity of mature trees, you will have adequate germination to keep the species present for years to come.

The old saying about not being able to see the forest for the trees has some truth to it when you are in search of river birch. You must train your eyes to look past the other trees to pick out the peeling bark of the vertical trunks or look for the leaves with teeth on the leaf margin resembling the teeth of an ancient crosscut saw.

Article

Article

by LISANNE

PETRACCA, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Carnivore Ecology, Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research InstituteIt’s 8:28 am when the text message comes in from Aidan Branney, MSc and technician for East Foundation: “Double ocelot.” For me, a new assistant professor of carnivore ecology at the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute (CKWRI), this is my first-ever “double ocelot day.”

From this moment, the ocelot trapping team, comprising researchers and students from CKWRI and East Foundation,

has less than 30 minutes to mobilize and head out of Kingsville for El Sauz Ranch. El Sauz is a 27,000-acre property owned by the East Foundation and serves as one of the last strongholds for the American ocelot.

Our 75-minute drive to El Sauz is punctuated with excitement. Ashley Reeves, DVM, Ph.D., research veterinarian at the East Foundation, knows this is going to be a long day.

Sponsored by JOHN AND LAURIE SAUNDERS

Dr. Reeves leads the capture team at El Sauz and is equipped with everything we need to safely immobilize and process an ocelot: immobilization drugs, needles, syringes, subcutaneous fluids, and monitors for vital signs. Most importantly is perhaps her equipment to extract semen from male ocelots, which is part of ongoing work in captive breeding of American ocelots.

Capturing and processing ocelots is a task that no one on the team takes lightly. The process requires swiftness, attention to detail, and caution. In addition to Reeves, Branney, and myself, we are assisted by CKWRI master’s student Tyler Bostwick and intern Georgia Harris.

During the 30 or so minutes it takes us to process an ocelot, we are conducting multiple tasks simultaneously: after injecting immobilization drugs via hand syringe, we must monitor vital signs, draw blood, remove ticks and fleas for disease analysis, inject subcutaneous fluids to prevent dehydration, and (if male) extract semen for the ongoing assisted reproduction project headed by Dr. Reeves.

When processing is complete, we inject a reversal drug and wait for the ocelot to regain mobility, at which point we release it back into the wild. It is always such a sight to see these magnificent cats vanish into the thornscrub, disappearing almost instantly.

The first ocelot from that day was a female that we named Valentina. It is rare to catch a female, as she was one of only two that we would capture in the whole capture season (to the contrary, we caught eight males). The second, a male and perhaps the most handsome ocelot I’d ever seen, was named Louis after my ailing father.

At the time, my father was intubated in the ICU after suffering a severe stroke. My brother held up the phone as I told my dad about the ocelot capture and the ocelot’s new name. I tried so hard to send the ferocity and strength of this incredible animal to my father to help him heal. I’m not much for superstition, but my father was removed from life support the next day and started breathing on his own.

The American ocelot has received much attention lately thanks to two documentaries partially filmed and directed on El Sauz Ranch by Texas native Ben Masters: “American Ocelot”

on PBS and “Deep in the Heart” on Amazon Prime, the latter narrated by actor Matthew McConaughey. In Masters’ footage, Dr. Michael Tewes, regents professor and the Frank Daniel Yturria Endowed Chair for Wild Cat Studies at CKWRI, related how he has personally witnessed the decline of ocelots in South Texas since he began his research in the 1980s.

The ocelots of South Texas are the only ocelots present in the United States, and are listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act. There are two populations: the “Ranch” population, largely on El Sauz Ranch and managed by the East Foundation, and the “Refuge” population, found at Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge and managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). We don’t exactly know how many ocelots are left in South Texas, but there may be fewer than 20 in the Refuge population and fewer than 120 in all of South Texas.

Threats to ocelots have been well documented. A burgeoning human population in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, with corresponding development of roads and infrastructure, has caused the two ocelot populations to become isolated from one another. In addition, vehicle collisions serve as a major source of ocelot mortality, as dispersing cats often don’t make it very far before being struck by traffic. CKWRI is currently working with the Texas Department of Transportation to better understand ocelot movements across roads and how to mitigate adverse impacts via crossing structures.

Despite the multitude of threats facing the ocelots of South Texas, there is currently a swell of momentum to help recover the species. First, the East Foundation, led by CEO Dr. Neal Wilkins, has led critical work in laying the foundation for collaboration and partnership with private landowners in South Texas.

Second, CKWRI and partners, including the East Foundation, USFWS, and the Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute, are committed to ocelot recovery and conservation, as evidenced by the creation of my position and the support of ongoing research into ocelot genetics, movement ecology, assisted reproduction, and habitat restoration.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, there is an exciting opportunity to construct a captive breeding facility at Texas A&M – Kingsville and reintroduce ocelots into South Texas.

Reintroducing ocelots to South Texas is still in its early stages, but has incredible potential to change the trajectory for the American ocelot. A possible reintroduction site has already been identified and, contingent on funding, we may be able to release young ocelots from a captive breeding facility or translocated ocelots from a source population, such as that in Tamaulipas, Mexico.

The work in my lab over the next decade will be dedicated to recovery of ocelots in South Texas. We will monitor information on key vital rates, such as survival and reproduction, and movement behaviors, such as den site selection and dispersal, so that we can better understand ocelot population dynamics and ultimately achieve species recovery in the United States.

I, for one, am hopeful for the American ocelot. In my field work in South Texas so far, I have found ocelots to not only be visually striking, but also tenacious and resilient. Ocelots are able to thrive in some of the toughest conditions on earth, making dens in thick thornscrub and regularly enduring temperatures over 100 degrees, as well as frequent drought.

Ocelots have been a part of the Texan landscape for thousands of years, and I hope that we can continue to make space for them in our world.

Editor’s Note: To learn more about Dr. Petracca’s research, go to https://lisannepetracca.weebly.com/

What he really meant was, “If we shoot that one, we’ll have to drag him out out of there rather than loading him in the back of the pickup.” I wasn’t disputing his decisions. Over a lifetime of hunting, I have packed more than my share of big animals out of “Hell’s Four Sections.”

Stopping in the shade of a mesquite, Charlie asked, “You going fishing after taking your nilgai?” I knew Charlie was not

“Don’t know what aggravates me more…ticks, mosquitos, or the sweltering humidity,” I muttered, swatting a pesky little vampire while mopping my brow, and watching a tick crawl up my pant leg. Thankfully, it later bailed when it sensed I had sprayed my clothing with Sawyer’s Permethrin.

Charlie Buchen, ace Wildlife Systems guide, smiled at my comment then pointed in the direction of sand dunes that separated us from the Gulf of Mexico. “Just saw a big blue bull cross between the dunes headed toward the live oak motte. We need to get a better look at him.”

For the past days, we had been literally chasing nilgai antelope over loose sand, traversing “sticker burrs,” cactus, and thorny mesquites. We stalked several bulls. Each time, Charlie said,”Mmmmm, we can do better…”

only a top big game guide but one of the better fishermen on the Texas coast.

“Yes sir, fishing with two old friends, Jim Zumbo and Rick Lambert.” Zumbo was long the hunting columnist for “Outdoor Life” and had an even longer career in outdoor television. Lambert had a most interesting law enforcement career. More recently his claim to fame is being the father of talented entertainer Miranda Lambert.

We planned to fish with Bamm Bamm Charters based in Port Mansfield. “Zumbo, Lambert, and I are firm believers of catch and release in a hot skillet.” Charlie smiled.

After catching up, we passed the nilgai he had seen. Headed back to the distant vehicle, we spotted a dark steel grey bull, a sure sign of maturity. His horns were obvious and dark, easily at least 9 inches long. A truly good bull. We conferred briefly then determined an approach.

Thirty minutes later, my .375 Ruger with its Hornady bullet dispatched my nilgai. After photos and field-dressing, we got the pickup, loaded the bull, and headed to the cooler. I planned to take all the delicious nilgai meat home with me.

Next day I met Jim and Rick. The three of us have hunted and fished with each other whenever our ridiculous schedules allowed.

We met Captain Chad Kinney and Tom and Mike Snyder, mutual friends who created Trinity Oaks, a charitable organization that takes wounded hero/warriors, veterans, children, and especially those with disabilities and serious health issues, hunting and fishing. We soon headed toward the soon-to-rise sun.

“We’ll start out fishing for red snapper. I have a couple of secret spots.” Captain Kinney hesitated, “Well, maybe not so secret. I took y’all there last year.” Finding that same spot, every time we dropped a lure, we caught red snappers. They ranged from about 8 to about 12 pounds. We soon had our limit.

I like fishing for red snapper. They are gorgeously colored, fight extremely hard, and are absolutely delicious fried or grilled. I have learned, too, the cheeks many discard when cleaning them are unbelievably delicious when prepared

over an open fire and seasoned with lemon juice, butter, garlic, and salt.

Soon as we caught our five-person red snapper limit, we headed to another area. We soon caught a couple of hard-fighting, excellent-tasting tuna.

Saltwater fish tend to hit harder and fight longer than freshwater fish, or so it seems to me. And I love it! Fishing for tuna, we also hooked a couple of brilliantly colored and equally delicious dorado or mahi-mahi.

A few minutes later, Zumbo hooked a 6-foot-long shark. Being the capable fisherman he is, Jim gave us all a lesson in how to fight big fish. Finally, he brought it alongside. The first mate unhooked and released it.

We were soon trolling for billfish. Years ago, while fishing out of Port Aransas, I caught a sizeable sailfish. After I brought it alongside, we tagged and quickly released it.

I was relaxing when I saw another billfish chasing one of the teasers. He

quickly moved toward a baited hook. Moments later, I had a marlin on the line! He fought bravely for several really long, muscle-straining minutes, to the the point I questioned why did I think this was fun?

The marlin jumped numerous times, then went deep. I pumped the rod and reeled in whatever line I could. Muscles in my arms and back all but screamed.

Then finally, I started taking in line. Minutes later I brought him alongside. As with my sailfish, we tagged and released the marlin without bringing him on board. We had taken a rough length measurement, marking spots on the side of the boat. “One hundred and eight inches! Obviously a male. Congratulations!” shouted the Captain.

I merely nodded, too spent to acknowledge. I was tired but truly thrilled to have caught and released such a great fish.

Yes sir, yes ma’am. Turf and salty surf! It’s that time of the year. After all, mankind cannot live on venison alone.

Oyster reefs are iconic habitats in Texas bays. These living structures, formed by younger generations of oysters cementing themselves to the shells of older generations, can provide critical ecological and economic benefits. The benefits include water filtration, habitat creation,

fisheries enhancement, and shoreline protection in our bays and estuaries, which make them essential components of healthy and resilient coastal ecosystems.

While many of the benefits provided by oyster reefs are well understood, we lack a comprehensive understanding of their

contributions to carbon capture and storage. The Coastal Conservation and Restoration Ecology Laboratory at the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies (HRI), Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, is working to understand the role of oyster reefs in the carbon cycle, which can be used to inform future conservation and management decisions.

The carbon stored by coastal and marine systems is often referred to as blue carbon. Salt marshes, seagrass beds, and mangrove swamps have been studied extensively for their ability to sequester blue carbon. These vegetated habitats bury carbon in sediments at a rate accounting for about 50 percent of all carbon stored throughout the world’s oceans annually.

Salt marsh, seagrass, and mangroves can store carbon at a rate 10 times greater than tropical forests, even though they cover a relatively small portion (less than 1 percent) of Earth’s surface. Known blue carbon habitats represent extremely efficient carbon storage systems, and early research suggests that oyster reefs can have very similar effects.

Although oyster reefs may not be regarded as conventional blue carbon habitats, understanding their potential for carbon storage may prove valuable in mitigating carbon emissions and increasing restoration investments.

Oyster reefs are fundamental components of Texas coastal ecosystems and economies. However, as much as 91 percent of oyster habitat has been lost globally, making oyster reefs more imperiled than any other marine habitat. Habitat restoration efforts can be very effective in ameliorating reef loss, particularly in Texas where larval oysters are often plentiful and warm waters make for rapid oyster growth.

Most restoration efforts involve placement of hard materials such as recycled oyster shells, river rock, and chunks of concrete or limestone in areas with suitable water quality for oysters to survive and grow. Larval oysters attach to freshly placed hard substrates and grow quickly, forming new reefs or enhancing degraded ones.

However, habitat restoration efforts are costly; quantifying the values of carbon sequestration by oyster reefs could unlock new funding opportunities to advance restoration activities.

However, quantifying carbon sequestration by oyster reefs presents major challenges due to the complexity of the processes involved. While some processes within the reef act as carbon sources, releasing carbon into the atmosphere, others act as carbon sinks, removing carbon from the atmosphere and storing it in a different form (Figure 1). In ecosystem terms, a carbon source refers to a system that emits more carbon than it absorbs, while a carbon sink is a system that absorbs more carbon than it emits. Oyster reefs capture and store carbon in two main ways:

• Oysters filter large amounts of carbon-containing algae from the water, some of which becomes part of the oyster’s tissues. The rest is released as waste, which is deposited on the bay bottom and becomes part of the underlying sediment.

• The complex structure of oyster reefs slows down wave action, allowing sediment to settle within and around the reef. This also helps trap carbon in the sediment.

Oysters can contribute to carbon emissions as shells are formed and when reefs become degraded. Whether an oyster reef acts as a net carbon source or sink depends primarily on the balance between the amount of carbon stored in the sediment and the amount of carbon emitted due to shell formation and other processes. We need to account for all these processes to develop accurate estimates of oyster reef carbon sequestration.

Existing estimates of carbon sequestration by oyster reefs in scientific literature vary widely, and methods of measurement

have been inconsistent. Some research suggests that oyster reefs release a small amount of carbon, making them a carbon source, while others claim that reefs store huge amounts of carbon, making them large carbon sinks. Recent studies have concluded that oyster reefs can store carbon in similar volumes to other important blue carbon habitats.

However, the amount of carbon stored by an oyster reef depends on various features such as its location and how it is managed. For instance, reefs next to salt marshes can

store more carbon than others because they prevent carbon-rich marsh sediments from eroding away. On the other hand, when reefs are harvested via dredging, stored sediments beneath the oysters and within the reef matrix can be resuspended in the water column, resulting in a reef that will likely not store carbon well.

An oyster reef’s vertical structure is essential to capturing sediments and keeping carbon in place beneath itself, so degraded reefs lose their ability to store carbon—and even release previous stores. While we don’t yet know exactly how much carbon oyster reefs can store, we do know that ensuring healthy reefs is essential to maximizing carbon storage. We can draw from previous research to determine needs and set consistent standards for our current research.

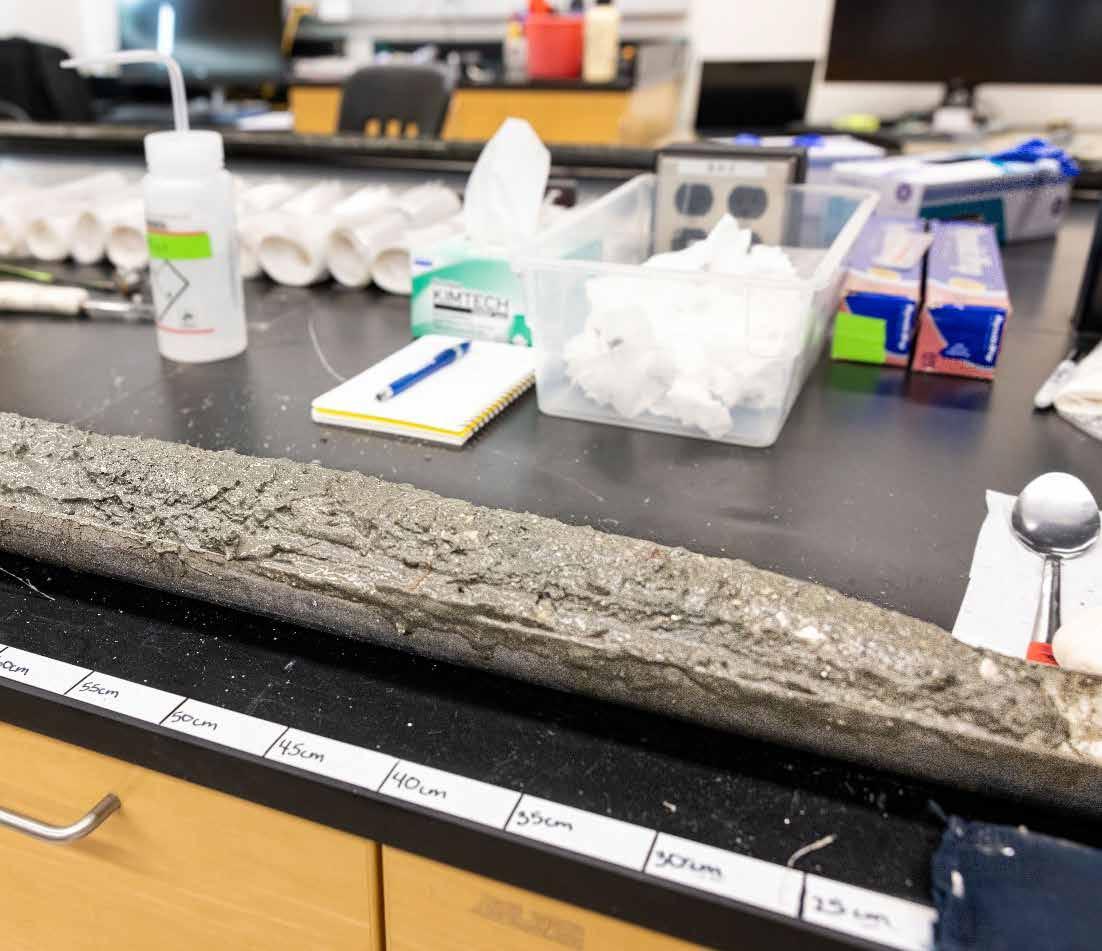

To quantify the carbon stored by oyster reefs and to better understand the balance between carbon sources and sinks, we collected sediment samples from a variety of restored and natural oyster reefs. In early 2023, a vibracore was used to sample through layers of oyster reef and sediments in St. Charles Bay, Texas.

The vibracore involves driving aluminum sampling tubes (cores) vertically through the reef and associated sediments using high-frequency, low-amplitude vibration. Core samples ranged in length from 4 to 10 feet to capture all layers of extant and historical reef; their diameter (7 centimeters) is purposely small to minimize reef disturbance.

The sampled reefs vary in age from newly restored (months old) to possibly thousands of years old, which will be determined through radiocarbon dating the shells. Once the cores are extracted from the reef, they are carefully sliced open with a saw and sectioned into 5-centimeter vertical segments to quantify carbon accumulation through time (Figure 2).

By analyzing and quantifying the carbon in the sediments and shells throughout the entire core, and accounting for respiration, shell formation, shell degradation, organic matter decay, oyster tissue, water filtration rate, and reef deg-

radation, we will determine whether individual oyster reefs are net carbon sources or sinks—and what factors contribute to their status.

Our research team includes Dr. Xinping Hu from HRI, Dr. Keisha Bahr from Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, and Dr. Benoit LeBreton from the University of La Rochelle, France. St. Charles Bay is a starting point for this research, but we plan to scale up this work to better understand the carbon sequestration potential of oyster reefs across the Texas coast.

Oyster reefs are promising blue carbon ecosystems—their carbon cycle is complex, and many questions remain unanswered. Although recent research suggests that oyster reefs have great potential in storing carbon, much more work needs to be done to determine the factors affecting carbon storage amounts and rates, and to incorporate this information into conservation and restoration planning. This research offers a glimpse

into the important role that oyster reefs could play in mitigating carbon emissions, and we are excited to play a role in finding answers to these questions. We have a lot of work to do.

This work has been generously funded by the Coastal Conservation Association, the U. S. Department of AgricultureNatural Resource Conservation Service and the Harvey Weil Sportsman Conservationist Award. This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, under agreement number NR217442XXXXC022. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In addition, any reference to specific brands or types of products or services does not constitute or imply an endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for those products or services.

$45,000,000 | Whitehall, TX | 1,650± acres

Rare offering of outstanding beauty, agricultural production, and in the path of progress. Rolling improved pasture with irrigation, exceptional ranch infrastructure, existing venue opportunities, and scenic high-fenced game pasture.

$5,995,000 | Johnson City, TX | 302± acres

Cedar Ridge Ranch is 302± manicured acres located in Blanco County, 66 miles from Austin and 24 miles from Fredericksburg. Amenities include a nice home, electricity, well, pond, blinds/feeders, improved whitetails, and exotics.

With complex species groups such as tarantulas, there is urgency to assign taxonomic groupings due to their unknown conservation status and overall vulnerable nature.

During a summer internship at the Rolling Plains Quail Research Ranch near Roby, Texas, I learned to take an interest in all wild things. With camera in hand, I traveled throughout the pastures for the few hours after sunrise and before sunset where I witnessed many subtle changes of the landscape—including a few of its seasonal secrets.

One of the secrets I remember well was a “migration” of tarantulas. For about a two-week period, I observed several of these impressive arachnids as they casually traveled across the Rolling Plains.

All of them kept an unwavering pace as I walked beside them, unmindful of me as they pursued some unknown objective. Some individuals would walk across my hand after first touching one leg on my palm to sense what I was. The startling synchrony of their long, loping legs caused me to question their whereabouts.

Very few people afford time to discuss the arachnid world, but this doesn’t mean spiders are unworthy of our attention. In fact, quite the opposite. Tarantulas keep to themselves, but they can be frequently observed at certain times during their “migrations.” Still, there remains a great deal of mystery surrounding their activities and movements.

Most species of tarantula are dark chocolate brown or black with some tropical species bearing striking color markings and patterns. Tarantulas display many typical spider features— eight jointed legs, a two–part segmented body, and a durable exoskeleton.

The tarantula’s hairy body and legs are heavily adorned with fine sensory

hairs called setae. The multiple simple eyes only detect variations in light, so the spider must rely on its tactile setae to navigate and detect vibrations from prey.

The large body can be divided into two regions, the cephalothorax and abdomen. Covering the body is a tough yet flexible exoskeleton that restrains growth. The tarantula undergoes a series of molts where it sheds the old exoskeleton through a process called ecdysis.

Males and females have divergent life histories. Because of the seasonality in Texas, it takes both male and female tarantulas about 10 years to reach full maturity. Males reach maturity and die after breeding, whereas the females are estimated to live up to 10 more years in the wild and up to 20 years in captivity.

Arachnids have two pairs of appendages near the mouth. The first pair are called chelicerae, and they form the fangs connected to a venom gland. In primitive spiders like tarantula, the chelicerae move up and down in direction rather than side to side as in most modern spiders.

This characteristic defines them as mygalomorphs, which include tarantulas, trapdoor spiders, and their close relatives. The mygalomorphs are believed to account for less than 10 percent of all the world’s spider species.

The second pair of appendages are the pedipalps. They are used for handling and manipulating food toward the mouth. Males also use them to transfer sperm to the female during reproduction.

Advances in radio telemetry technology have enabled researchers to gather insights into the hidden lives of these unique arachnids. To learn more about

tarantula movements, Margaret Janowski-Bell, Ph.D., biology professor at Victoria College in Victoria, Texas, tracked tarantulas fitted with miniature radio transmitters in the Rolling Plains region. The transmitter was attached to the tarantula’s cephalothorax using a waterproof adhesive. She monitored their progress throughout the breeding season.

“The focus of the research was on male tarantulas, and the reason was because there was a lot of anecdotal evidence that tarantulas moved en masse and in the same direction,” she said. “If you watch them cross the road, it seems like they are all going to the same place. We wanted to see if that was true—how far they were going, where they were going, and why.”

Determining the driving forces and the navigational cues of the male’s seasonal movements has continued to be a mystery. Mass movements are rarely reported and have been attributed to ideal weather conditions.

“When you start paying attention to which direction the males are going, it turns out they’re going in all directions, and

the hypothesis is that they’re looking for females,” JanowskiBell said.

After their final molt, male tarantulas leave the protection of their burrows in search of potential mates, usually between June and December. The females remain loyal to their burrows and do not disperse. Tarantulas witnessed outside the burrow are almost guaranteed to be mature males.

Janowski-Bell described an easy method of identifying the males. “If you look at their front pair of legs, you will see what is called the tibial spur. It is a spur that comes down on either side, and they use that when mating. The male pushes the female up to get under her abdomen, and they hook her fangs with the spurs.”

The tibial spurs hook the female’s fangs or chelicerae to escape being her next meal. The female is capable of unhooking herself, and some males succumb to cannibalism; however, JanowskiBell’s findings demonstrated many males survive their encounters and visit multiple burrows. The assumption is the males

have multiple mating attempts until their energy reserves eventually deplete.

Prior to mating, the male will spin a silk web and deposit a tiny drop of sperm on it. The male draws the droplet into his pedipalps which he will use to insert the sperm into the female’s reproductive tract. Every species of tarantula has a uniquely shaped embolus at the tip of the pedipalps which help transfer the sperm.

According to Janowski-Bell, “The threedimensional shape of the embolus on the male is complementary to the shape of the female’s reproductive tract. It is like a lock and key mechanism for isolation of species in tarantulas.”

Tarantulas occur throughout Texas and the Southwest region in grasslands and open brush country. Individuals inhabiting arid climates will typically shelter in natural cavities or burrows they excavate or that have been abandoned. Tarantulas produce silk but do not create webs for capturing prey.

Many species remain at the entrance of their protective burrows waiting for an insect or caterpillar to pass by or trip one of many silk threads extending from the burrow entrance. They occasionally wander short distances from their shelter to actively search, usually at night.

The tarantula’s size lends them the advantage of tackling a wide range of prey. Spiders are predators and typically feed opportunistically on whatever presents itself. This may include taking insects and other invertebrates, as well as small lizards, frogs, and mice.

Tarantulas are not without their own natural enemies. The most dramatic spectacle exists between the tarantula and eloquently named tarantula hawk wasp. Sporting brilliant rust-orange wings and a dark metallic blue exoskeleton, the tarantula hawk is a parasitoid wasp—a parasitic organism that kills its host—with a 3-inch wingspan and 1-¾ inch body.

A reproductively active female wasp will first seek out a tarantula burrow. The drama unfolds as the insect and arachnid wage war and ends when the wasp paralyzes the tarantula with its venomous sting.

The wasp drags the paralyzed spider to its own burrow and seals the tarantula inside with a single egg. The egg hatches into a larva that ravenously feeds on the tarantula from the least vital organs to the most vital organs. The larva completes its metamorphosis and emerges as an adult wasp to continue the perpetual parasitoid life cycle.

Tarantulas can deliver a venomous bite; however, the venom’s potency to humans is nonlethal except for allergic reactions. Tarantulas are reluctant to bite because venom is a costly and time-consuming to create. A provoked tarantula will assume an impressive defensive position by raising its front legs and holding the fangs forward.

If this display fails to dissuade an attacker, the tarantula has another defensive method. The hairs on the tarantula’s abdomen are equipped with microscopic barbs. Janowski-Bell explained that these hairs, called urticating hairs, can be dislodged when the spider kicks its legs over its abdomen, creating an airborne cloud of barbed hairs directed at the attacker.

“It’s thought the urticating hairs are actually a defense against the mucosal membranes of mammals,” she said. “When a mammal sticks their nose down into the burrow, they get those hairs in their eyes, and it definitely stops them from excavating pretty quickly.”

Contact with the skin can cause intense irritation. Greater concern comes from contact with the eyes or inhaling the irritating hairs. Only tarantulas from the New World possess this unique deterrent.

An estimated 900 tarantula species are spread across the world in the tropical and subtropical regions. There are many unknown pieces of information pertaining to their taxonomy and conservation status, including species found in Texas.

“I don’t think we have any endangered tarantulas in the United States; however, their taxonomy is so up in the air that it is difficult to say if we have or don’t have any unique genetic populations,” Janowski-Bell said. “We could have genetically diverse and valuable populations that we don’t know about.”

Due to the high taxonomic uncertainty surrounding tarantulas, many questions about how many species occur and the extension of their ranges remain. Knowledge of these genetic populations is necessary for making conservation decisions and mitigating the future loss of species.

Difficulty arises when identifying tarantula species in the field. Janowski-Bell explained that researchers require mature adult specimens to establish a species’ identification, and the researcher

• Rancho Rio Grande - Del Rio, TX

MLD 3, $15.50/ac, Hwy 277 Frontage, water, electric.

– 25,685 ac, Axis, Whitetail, Duck & Quail

ο Some Improvements

ο Live Water: Rio Grande River, Sycamore & San Felipe Creeks

– 1,850 ac, SW Intersection 693 & 277, runs south along 277.

must sacrifice the specimen. Molecular DNA sequencing is often necessary and provides a more reliable method for identifying morphologically similar species than by using physical characteristics alone.

With complex species groups such as tarantulas, there is urgency to assign taxonomic groupings due to their unknown conservation status and overall vulnerable nature—long-living and slow maturity coupled with heightening pressures from human disturbances. The need for accurate phylogenetic research is tied to improving our understanding of biological diversity, natural history, and identifying cryptic populations.

Tarantulas may possess great possibilities in the scientific community. For example, researchers are constantly analyzing key components from venom for their potential use in the medical field.

“Understanding the biology of tarantulas is important. Tarantulas have venom that is full of proteins that we might be able to synthesize, but producing the original recipe can be incredibly difficult. It does have the potential for venom research,” she said.

The ecological significance of arachnids is also an important contribution to the stability of the ecosystem. Understanding the function tarantulas play in maintaining insect populations and their position within the food web can help indicate the quality and changes linked with the environment.

With every encounter, I am increasingly fascinated by the intricate characteristics of these giant spiders. Their intimidating size and appearance often cause people to perceive them as “scary.” As I have seen more of them, I’ve redoubled my efforts to photograph and highlight this often overlooked yet charismatic species. As researchers continue to explore the hidden lives of tarantulas, more will be uncovered, and new questions will arise.

“Every question we answer just leads to more questions, which I get really excited about. That is the great thing about science. We will never run out of questions,” said Janowski-Bell. “Tarantulas have an amazing life history. I think that if people knew more about tarantulas, they would feel a lot more affection towards them. They are gentle giants.”

Crabbing is a tasty summertime endeavor up and down the Texas coast.

The pursuit is relatively simple and many of the most productive crabbing locales are accessible from shorelines, jetties, and piers. The gear necessary for enjoyable outing is inexpensive, and in that regard, it’s an everyman’s recreational opportunity.

Crabbing also is tailor-made for introducing youngsters to the outdoors and to the conservation of species that have a direct

correlation to the health of our saltwater ecosystems up and down the coast.

Some of my fondest childhood memories occurred on annual family trips to Rockport, which features some of the most accessible crabbing waters on the entire coast. The anticipation of setting out traps and crab rings off the pier and the subsequent inspection that yielded even a single blue crab was cause for celebration. However, there were almost always many more crabs, providing ample wild fare for a proper seafood boil with just a little bit more effort.

Blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) typically lurk near sandy bottoms lined with sea grass and usually are found in bay systems. They have blue claws, dark backs, and white underbellies. Stone crabs (Menippe adina), which are brownish-red and have a larger right claw, typically prefer rocky structures such as jetties that protrude into the Gulf.

A blue crab’s diet differs from freshly dead to freshly caught food, including small bait fish. Crabs also will eat each other, and the stone crab’s powerful larger claw can be used to crush the shells of crabs, oysters, and other mollusks.

Some of the best crab habitat is nestled close to manmade structure near shore. Prime locations include the area around boat docks, marinas, bulkheads, piers, and especially bait stands or fish-cleaning tables, where scraps always get scooped up quickly. Other places to seek out include brackish areas and estuaries that harbor a number of different food sources.

Crabs may be harvested for food or bait with a valid fishing license and a saltwater fishing stamp endorsement, but those taken for personal use may not be sold. There are no public waters, seasons or times closed to crab harvesting other than during abandoned crab trap removal program dates.

The trap removal program, which marked its 23rd year in 2023, closes bays to crabbing for a week in February. Traps in the water during that period are fair game to be legally removed. Derelict crab traps are a blight along the coast and often end up killing many different species through “ghost fishing.”

There is no daily bag or possession limit for blue crabs and stone crabs, but they each must meet a minimum criterion to be taken. Blue crab may be legally harvested when they measure 5 inches across the widest point of the body from tip to tip of the spines.

A legal stone crab has at least a 2½-inch claw, measured from the tip of the claw to the first joint behind the immovable claw. The larger claw is the only portion that may be retained and you must return the body of the crab to where it was caught. The crab’s claw will regenerate, typically within a year, according to TPWD.

A blue crab’s sex can be determined by the abdominal flap or “apron,” which in males is shaped like an inverted T; the females’ aprons are broader. Spawning season runs from December to October and peaks during spring and summer.

When carrying eggs, females are termed “sponge” or “berry” crabs. It is illegal to keep them. It is also illegal to possess female crabs that have had their aprons removed.

After mating, females travel to saltier portions of the lower bays and Gulf, while males remain in the estuaries, according to TPWD. Blue crabs suffer in low oxygen conditions and manmade and naturally occurring pollutants can have serious consequences for the population.

Parasites also are common on crabs. Barnacles, worms, and leeches attach

themselves to the outer shell; small animals called isopods live in the gills or on the abdomen; and small worms live in the muscles. However, most of these parasites do not affect the life of the crab, TPWD notes.

Crabbing devices are varied and feature some restrictions, as noted in TPWD regulations.

The simplest legal device is a throw line — a baited line without a hook — which has no restrictions. You can tie whatever smelly lure you prefer onto a piece of strong twine that’s long enough to reach the bottom and drop it from a pier or the bank. When a hungry crab latches on,

slowly retrieve the line until you see it and then use a net to scoop it up and place it in a bucket.

Another common way to fish for crabs by hand is to use a crab net, which is termed an umbrella net by TPWD. It features two rings attached by mesh with the larger top hoop attached to a pull line, and when baited and dropped to the bottom, the device folds flat.