Tanner

the Sanctuary

May 2021

thank you

Deanna and Ruben Vargas (for sending care packages and loads of love always); Daniell Morales (for being my biggest believer); Jillian Crandall (for being a constant supporter and opening the door to what the project really wanted to be); Dan Rothbart (for meaningful conversations and shared space); Cate Cribb (for activist debates and quality brainstorms); and my Queerness (which I have found through these five years, in and between the architecture).

Queerness, once my greatest weight, has now become my greatest strength. This project has, in many ways, become a symbol of that transformation; both personally and academically. This project is a love letter to queer folks surviving, like I was, in places not meant for them. May we keep the faith.

This thesis aims to subvert traditionally heteronormative structures of power, formally and sociopolitically, in order to reclaim space for queer people in a stubborn landscape.

In subverting the physical and ideological typologies of a catholic church and military armory, the proposal utilizes familiar forms to house unwelcome identities. The adjacency of spirituality and violence act as reimagined mechanisms of covertly queer protection.

Drawing upon decades of queer codes, theories, and forms, the design theorizes ways in which a jeopardized minority population may covertly, then over time overtly, inhabit typologies that are traditionally harmful to them. Queer theories and design thinking guide a reimagined design timeline that liberates architecture to become a conscious force which designs, builds, protects and transforms the proposal during and after construction. In order to accomplish this, critiques on heteronormative conventions— architectural, representational, sociopolitical —must be formed. The tools of the oppressor effectively become the defenses of the oppressed.

Though harmful realities of the present landscape must be addressed, the proposal holds hope that the defensive tactics will only be temporary, and the designs being dispersed from the armory may effectively, over time, work to challenge and change the metaphysical landscape

This thesis aims to understand, investigate, and eventually exploit traditional notions of power, permanence, protection and performance across design disciplines. This thesis began as an investigative critique on the interdisciplinary definitions of “normative,” in theoretical, representational, sociological and even physical terms. Naturally, personal interests in fluid fashion, informal urbanism, activist art and queer theory began forming connections to researched arguments on cross-contaminated fields (such as architecture and fashion).

As the design process began, these ambitions began intersecting towards new theoretical grounds in which the concept of “queering” could be filtered through many transdisciplinary lenses towards an architecture of subversion, celebration, protection and restoration.

pedagogy

The taught, practiced, and normalized boundaries of architecture must be expanded beyond formal beauty, technological progress, and futurism alone. Our discipline is moving towards a future of hybridized approach and diversified authorship, two queer horizons upon which this thesis finds great hope. As this thesis took shape in the shadow of a future-formalist school pedagogy with its own conservative detractors, I was able to find my own design purpose. In many ways, the friction formed new tendrils of creativity and the both-ands became foundational to something much bigger than any single plan, project or person.

I have been able to realize and develop a set of design values over the course of the Final Project sequence. Each position argues for socio-spatial hybridization and queered inclusivity. I am no longer satisfied with formally-prioritized work, as such proposals are doomed to superficial aesthetics if they do not have a stake in, or [re] consideration of, urgent and emergent issues that threatened communities—anthropological or not—may face. Five central themes guided the research foundations of this thesis project:

The Denouncement of Permanence — In a world of continual impermanence, from ecological transformations to socioeconomic shifts, we must formulate inclusively hybridized approaches that lead to final designs which do not see themselves as static interventions, but rather fluid propositions of nonlinearity. The illusion of permanence must not proliferate in a world of open systems and dynamic change; temporality can be a design tool rather than avoided reality.

A Challenge to Binary Thinking — Our discipline’s obsession with grids, binaries, silos and tradition must be questioned to reflect an increasingly dynamic and decentralized world. The linear perspectives & top-down approaches of past must reconcile with today’s digitized, globalized context of constant, rapid flux, where static grids of blackand-white are less acclimated to address the gradient of issues and publics we now have.

The Hybridization of Discipline — We can no longer ignore the environmental and sociopolitical contingencies facing architecture; the design profession and its surrounding vectors must perforate the bounds of communication and collaboration to foster meaningful, empathetic change that is expectant and inclusive from the origin of design to its implementation in diverse contexts. Beyond lip service, we must extend and engage to foster collective resilience and progress.

A Reconsideration of Authorship — The agency of the architect has eclipsed the agency of the inhabitant; designs for the communities we serve must include adaptive networks of participation, centered on the constituents and their uniquelyunderstood needs. The definition of authorship must be challenged without fear of new architectural norms or considerations.

The Queering of Space — Relating to binary opposition, the unique capabilities of queer theory to respond to and reform typologies of oppression in evermore fluid modern contexts must be considered under an architectural lens. The identities, subcultural traditions, and spatial potentials of ‘queered space’ must be studied as its own distinct methodology, capable of extending beyond any single category of oppression.

These perforated lines of inquiry have led to a larger discussion on what it means to hold, challenge, or subvert normative notions of discipline, representation, and design implementation. Through the emergent field of queered design, I aim to announce several strategies, still in development, of how design might be effectively “queered” towards more subversive, inclusive, and discursive futures.

As these five pillars of inspiration began forming the foundations of the design proposal, my personal experiences as a queer person from the south became something to productively draw upon. In the context of my academic career, of which this design research is a culmination of, queerness has been inescapable. I entered my first year of architectural education as a closeted queer in unfamiliar territory, both physically and academically. As I progressed through the program and my own personal revelations, a new vocabulary of named perspectives was able to emerge.

Once I felt my thesis turning towards the region that so negatively affected me in my formative years, terror and exhilaration seemed to grasp me simultaneously. The idea of utilizing design and theory to address pertinent issues of inequality, directly related to the self-discovery I have been able to make over these five years, became a passion I see lasting long beyond the production of this book. In many ways, this project is a shimmering encapsulation of my growth over these first years living in truth, with all its pain and potentials.

The Sanctuary for Queer Design and Defense represents my first foray into what it means to subvert architectural norms, specifically related to the rigid binaries and overwhelmingly heteronormative structures it currently operates within. What began as a social argument soon branched towards formal (in the typologies addressed), then representational (in the shimmering of queer design), and eventually political (in the suggestion of how such a subversive project might be built in a landscape that loathes it). This thesis aims to open a door of inquiry into what it means to intersect queer ecologies with architectural conventions. What does it mean to queer the landscape?

history & precedent

My research during the fall semester progressed in four phases: (1) ecological hybridity, (2) history/hybridization, (3) informal ephemeralities, and (4) urban edges/ethics.

I instinctively reached beyond the discipline of architecture and dove into the particular abilities of fashion design. I was drawn to its capabilities of integrating hybrid elements, from collaboration to fabrication, and then explored various film architectures and landscapes in efforts to understand the gradients between ecology and hybridity beyond and including the field of architecture.

This line of exploration led me to question how “architecture” has historically considered itself—through styles, eras, social classes and internal movements— and where its current “crisis of agency” (amid growing interdisciplinary integrations) might exist.

When I began considering potential sites and sociology, I returned to a continual obsession in researching the informal sides of cities and how rapidly-evolving socioeconomic systems affect and perpetuate certain modes of design over others. From there, I found a string running through all of my research interests: division, formally and socially, on the urban scale.

One of the most impactful elements to me personally in the forming of this thesis has been the complicated development of my own questions and ethics related to our field, and how it has, or more excitingly can, operate.

The perforation of discipline and crosscontamination of ideas has become a moment of investigation that underlies many aspects of this thesis, both theoretically and in the design proposal itself. Marrikka Trotter and Esther Choi’s Architecture at the Edge of Everything Else was a seminal text of reference. I now believe that creative subversions, or at the very least fluid explorations, of traditional power and agency are crucial in the progression of future urbanisms. These subversions are uniquely able to work towards a more inclusive design process that embraces the fluid nature of things rather than working against them, and adopt a readily queer perspective more capable of withstanding uncertainty and change.

This stance beings into question many emergent topics, the primary ones of this thesis being: challenging permanence and temporality, embracing new definitions of authorship, forming new modes of nonbinary thinking and form-making, and exploring what it means to “queer” design against more traditionally static and often fallacious considerations of spatial design.

typology & form

A natural line of research dove into historically queered spaces. Sites of coded queer use, across hundreds of years, began forming a kit of forms and socio-spatial relations: pleasure gardens, bath houses, cruising spots, and other sites of exchange began forming relationships between “planned” formal uses and equally, if not more often-enacted “informal” uses. Not all informal or subcultural use scenarios are deemed “negative” by the dominant public, and both utilize the same spaces regardless; so how can we begin designing with an air of creative expectancy for the diverse realities of the built environment?

The reality of informal and/or temporary use became a consistent consideration of the design research, specifically in its connection to queer populations throughout history seeking refuge in creative spaces.

research & working methodology

In the case of “Operation Soap,” a series of brutal police raids in the Toronto bath houses of 1981, a moment of crisis reveals how spatial dynamics are often inseparable from social dynamics. This juncture of conditions and identities best describes how I began thinking about the proposal physically.

Though I knew that “queer space” would be an elusive subject, the potentials of its architectural and social implications kept the explorations alive. This is where I began connecting the physical struggles within city spaces to more metaphysical struggles of politics and ideology; a clearer definition of site, user, and specificity evolved. In a review of Stud: Architectures of Masculinity by Joel Sanders, Ira Tattelman argues for a realization of the city’s larger straightness that rings unfortunately true still today:

“The queer use of space offers fluctuating positions; queer people assert their flexible identities rather than take on the identities imposed by others. They live on the margins, critical of, or at least distant from, the norms that most people take for granted. Imagine a culture where the institutions of heterosexuality do not determine human relationships and order society. The presence of same-sex or transgendered partners on the streets, kissing or holding hands, and the discomfort and social anxiety it can cause help one understand how straight the city is.”

a shimmering

Kate Thomas, Historian and Professor of Literature at Bryn Mawr College, gave a virtual lecture entitled “Lesbian Arcadia” at the Harvard GSD on February 18, 2021. I feel it is a necessity to call out a particular quote that I kept coming back to, most especially as I navigated the representational explorations of the project:

“...material things are not inert, but instead have shimmer and spark...shimmer is a word that means the play between shadow and illumination, light that is flickering[...] or tremulous, capable of casting new forms and relations. A garden is not made, but is instead always becoming. It is in flickering motion between hard and soft surfaces, built and planted elements that are all always in states of growth and decay. Some elements of the garden will last for centuries and others for less than a season.”

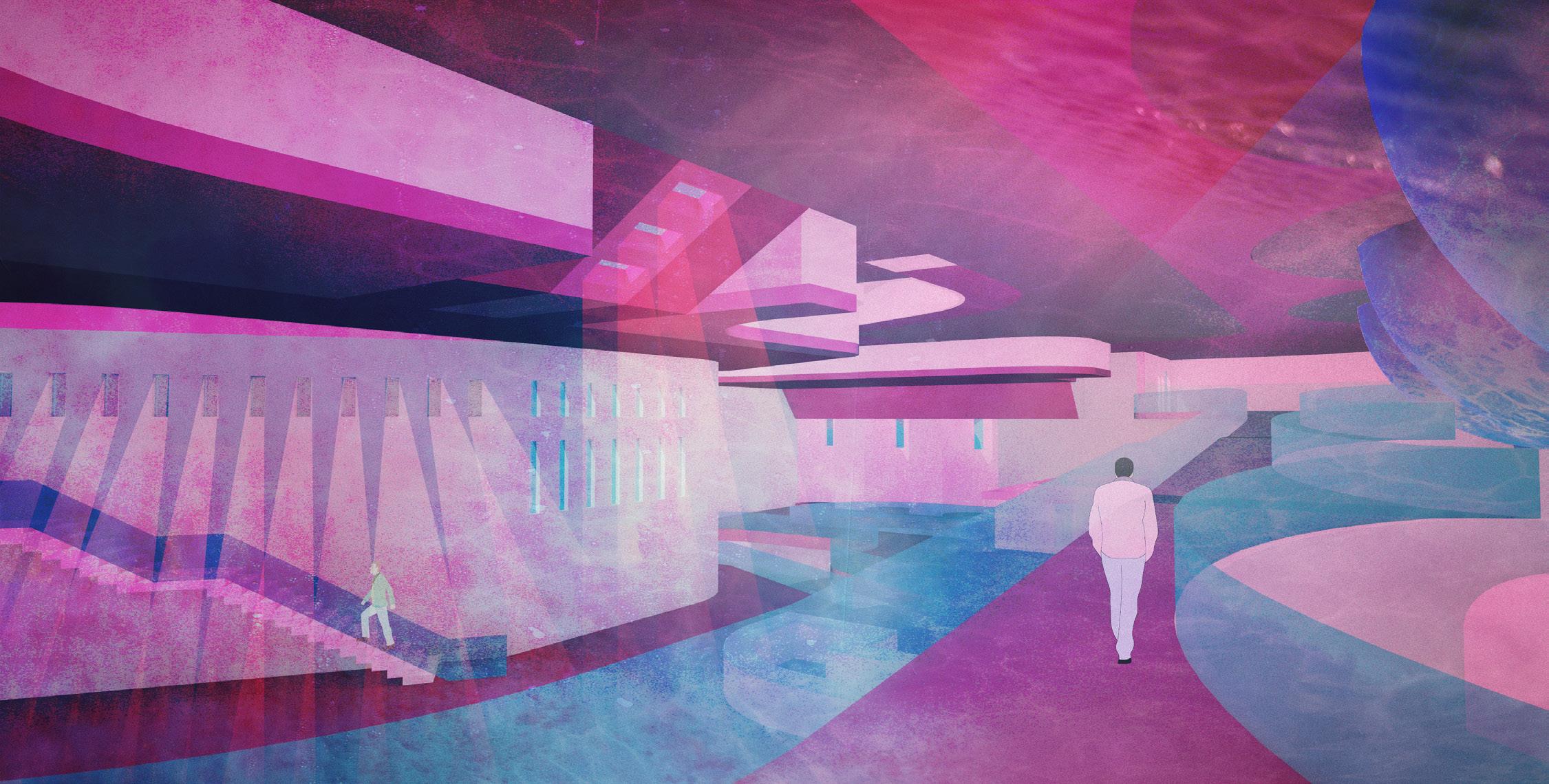

Before I had the chance to hear that lecture, I began exploring representationally what a slippage of color, light, and cast shadow might begin to look like. I made the image at right early in the design semester, before a schematic emerged, and kept finding its energy hidden throughout my progress.

The basis for the image came from an interest in movement, both in cinematics and sound. I spatialized the bombastic sounds of SOPHIE, a trailblazing musician and producer, and extrapolated geometries from the enigmatic “shimmer” from the film Annihilation. What I found, or kept finding, was meaning in the dimensions and shimmerings of space and their potential relations to identity. he notion of “shimmers” is further explored in the Master of Urban Design thesis project, “A Queer Hinterlands.” (2022)

As the thesis questions and stances formed in parallel, I turned my energies to siting: where do these complexities exist currently, and how might I begin connecting my perspective as a designer to my emerging design obsessions? Urban division became the impetus for site investigation: where do instances of socioeconomic segregation exist, and how are they mirrored in urban forms and metaphysical divides? How is a binary spatialized?

Sao Paulo, Brazil, and their informal irregularities sprawling against proximal wealth; , and their intersectional injustices of race, capital, sociology, development and “the American dream;” the Bible Belt states in the Southern US and their legislative outliers stemming directly from socio-evangelical conservatism. As I began designing in Missouri, I found inspiration in a site situated directly against a large Basilica. My interests in queering design were most energetic here, but I realized the quantitative issue may not be most prevalent, or

Naturally, I turned to my hometown in Texas, where small town life was not a welcome place for queer folks and other minorities. I began an investigation terminology of “queer” as a diversion from the more conceptual strategyforming basis I had so far been investigating, and found new ground in the hauntingly familiar.

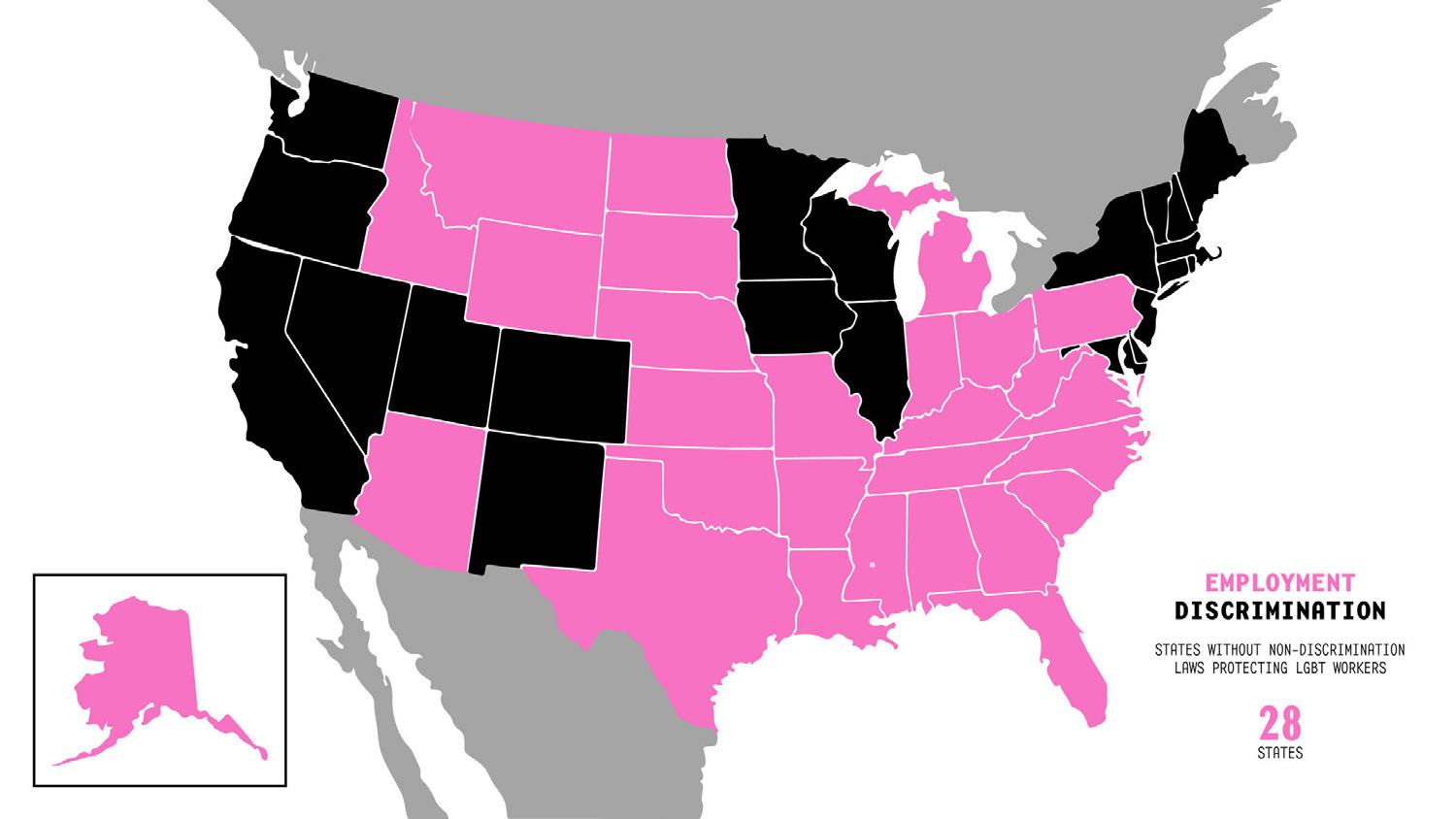

Though part of my thesis aims to critique the static linearity of normative maps, and the repercussions of their considerations, I will begin with a standard quantitative mapping of the US under the lens of LGBTQ rights and protections, specifically situated in the larger “site” of the bible belt.

Though the lines are clear here, the gradients of queer intolerance are not so distinct.

pendulum swing

The previous maps, sourced from the HRC, were made in 2021. As of March 2023, the landscape has become even more intolerant towards queer expression and this project demands revisiting with the constant and unflinching waves of anti-queer violence, disinformation, minority rule, and fearmongering we now face. A few damning updates are detailed in this spread.

Figs. 19 — Changes over a single calendar year (2021-2022) are already significant before taking into account the unprecedented barrage of anti-queer legislation and media representation in 2023. Many states, including and especially my home state of Texas, have gone from stagnant legislation to bigoted overhaul with seemingle endless resources (mis)directed towards anti-queer legislation and its required economy of fearmongering.

2022

States with no anti-LGBTQ bills introduced/not in legislative session (14 States & DC): Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, Texas, Vermont, Washington, Washington, DC

States that have introduced anti-LGBTQ bills (23 States): Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming

States that have signed anti-LGBTQ bills into law (13 States): Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah.

queer cartographies

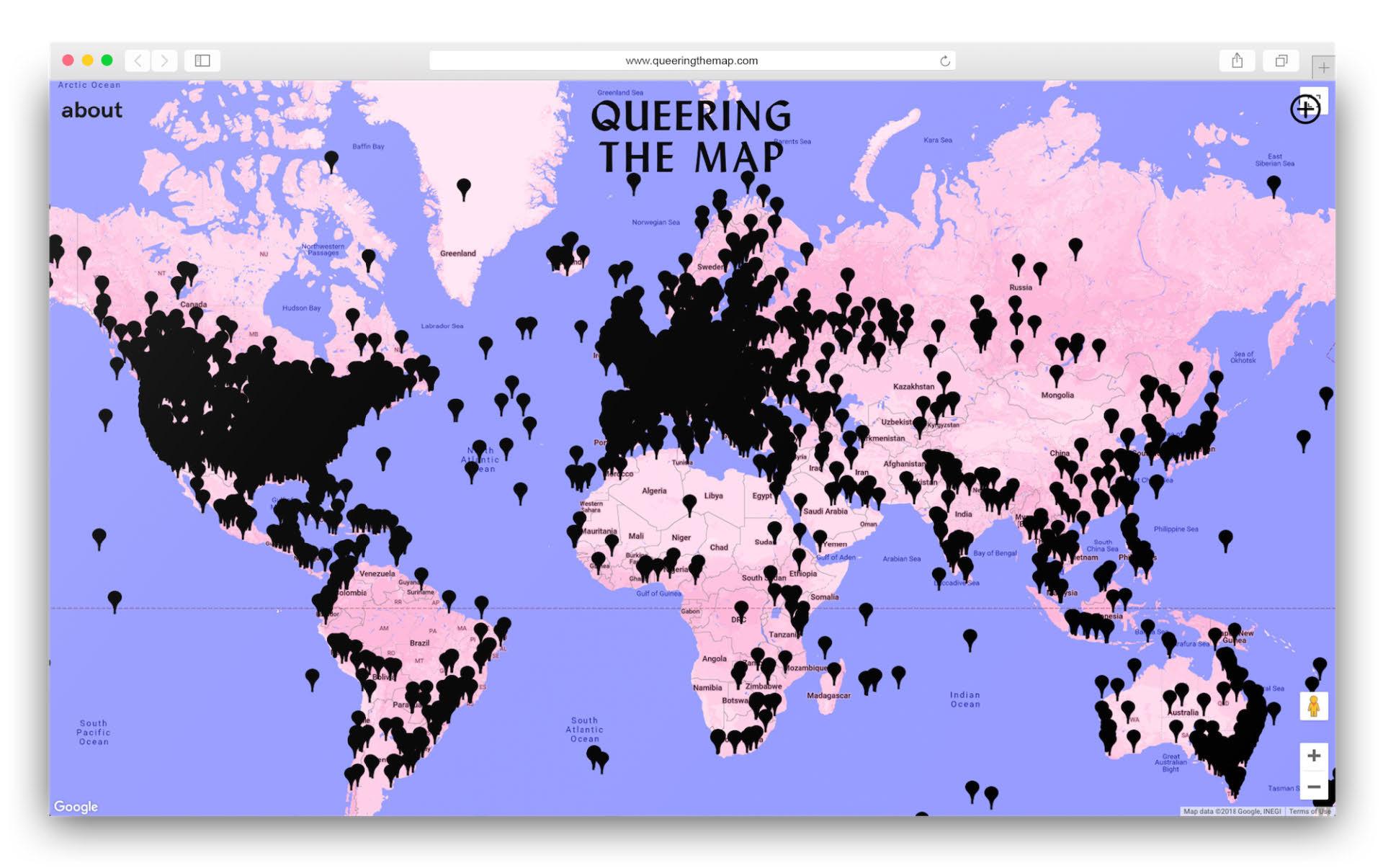

To shift towards less familiar cartographies, queer designer and researcher Lucas LaRochelle has created ‘Queering the Map’ as a communitygenerated counter-mapping platform that digitally archives queer experience in relation to physical space.

One of the most impactful concepts I took from LaRochelle’s work on queer geographies is its stance on the indeterminate reality of intersectional spaces. Though maps are most often used to orient us, this digital archive of queer space resists the academic desire to “make sense” of the map and instead delights in the potential to get lost while navigating its interface. That concept, paradoxically, is inescapably queer for many instances on the map and aligns with its mission.

Some struggles that queer folks have faced in Jackson became reflective of the design’s program and performance: “where I slept after my father kicked me out,” ... “on my first date at 16...as we kissed I felt positively holy,” ... “outed without permission and bullied into dropping out of high school.” A particular quote has gained deep meaning for my project as it has progressed:

“this is where I had to attend catechism classes as a teenager. there were about six regular attendees in my class: I was a closeted gay girl, there was another gay girl, and then a gay guy, all in my class at high school. it was a strange experience; we weren’t friends, but when the lessons veered into overt homophobia we were united in our stubborn silence.”

Catechism classes include a series of fixed questions, answers, or principles relating to the Christian religion, often heavily interpreted, to be given in a question-and-answer format.

This mapping of a queer experience in Jackson, relating to homophobia in a space meant for holy welcoming, reads especially devastatingly in terms of this proposal.

farish street

The chosen site is located in the Farish Street Historic District, a mixed-density area that is in equal proximity to the state capitol, downtown, commercial zones, residential fabrics, and various parks. This area is the northernmost part of the district which was once known as “the black mecca of mississippi” in the 1950s, but is now composed of mostly derelict or abandoned structures due to many years of failed upkeep and investment attempts which cannot be separated from demographics and histories of racism.

The historic record of “developmental promise” in the area has been consistently restarted, reinvested, and failed due to socioeconomic struggles and questionable-at-best developer strategies. The progressive mecha of the 1950s is far removed from today’s portrait, and I’ve aimed to utilize policy subversion to address the project potentials.

sanctified site

There’s a strong sense of religion here in terms of physical presence, with a network seemingly already at play. The context exists today as mixedfabric historic district of residential zones, industry, several churches, and urban disjunctions such as a grassroots skate park and a handful of dilapidated shotgun houses.

After I began designing on the site, I found an adjacent building named “Lizzie’s Takeout” that I assumed was just fast food. As it turns out, it is a food joint, but they are heavily sanctified and often do community outreach through food services. The quote on the red cross comes from the bible, equating the Lord to a beacon of rest.

design overview

The full extents of the project can be seen below. The three typologies are arranged strategically, phased to grow through the site while creating conversation within and underneath the context of their typological precedents. This is not a single build construction, but rather a planned phasing scheme of multiple structures and publics at work.

The typical scale of these typologies—grandiose, intricate, expansive—is, notably, not sacrificed.

project development

The project developed first in section. Though I began by drawing the traditional catholic church plan, I only used it as reference for the eventual explorations to be made in section. I first aimed to soften the orthogonal sharpness of the section, both by perforation and added curvilinearity. I also wanted to challenge the predominant source of light, which traditionally filters in horizontally through stained glass, by creating multiple angled skylights to let light filter in from above. Playing further with the sectional traditions of the church, the geometry of the dome was carried down into a stage pit, which runs below a nontraditional descending nave. Spatial hierarchies are queered alongside potentially queered use case scenarios for a traditionally fixed and stable typology.

Before diving into the programming, I think it’s necessary to bring to light a quote by queer historian George Chauncey that I found especially powerful in terms of this project’s stance:

“There is no queer space; there are only spaces used by queers or put to queer use.”

In harmony with Chauncey’s definition, I would argue that the most impactful form of subversion is not in the design of space itself, but the occupation of it, and all its layered meanings. The phases are indebted to many interdependent actors and are only successful when a series architectural norms liberate themselves from imposed or inherited positions.

programmatic synthesis

The programming of each typology is more fluid than fixed, with abstract definitions relating to larger experiences. They are pointedly divided into three: RECLAIM, RESTORE, and REFORM.

In the development of the site plan, which took many iterations and continues even today in exploration, I kept exploring the notion of shimmer. From the inverted shadows and surface reflections to the relational glow between building and landscape, the notions of color, hue, statics and slippage point towards desire and possibility without much fixity.

For the plan cuts, a similar mechanism of protection is at play. They are not meant to be traditionally normative in clarity or convention, but rather act as evocative images only meant for those who have seen its interiors. There are various sets of plans.

A question that I kept coming back to was frustratingly simple: who enters, and how?

Above is a gradient diagram of two different passerby and their relation to the building’s only main entry. In dotted blue is the everyman, maybe on their daily walk, who happens to pass by the site. Seeing a church elevation, bell tower, and likely open doors, they come in, see the altar, and leave, having satisfied their curiosity. In pink, however, is the intended audience of the proposal: those that do not fit under the heteronormative umbrella. This is their space in a world not designed for them.

In order to control this point of entry with nuance, the plan opts for a “faux altar,” in which only those “in the know” are able to pass through, drawing on decades of queer coding. If you know you know.

existing flat

waterways (-)

sensual mounds (+)

filter trees

plantings

The “queering” is carried out onto the landscape and used as a filtering mechanism. Waterways flow from a coded entry past the exedra, receding under the monastery & reemerging to snake through a protected landscape before resting directly under the baths. Gentle mounds offer visible and occupiable protection depending on their adjacencies. Trees are the primary source of visual covertness, planted strategically to limit eyesight views and/ or signal coded entries, like the one directly under the faux altar from the left street into the exedra gardens. Plantings, such as flower beds and trimmed hedges, offer flexible, ecologically architectural spaces for informal intimacy and formal enjoyment.

The Control Center is used as a defense mechanism for the protection of the sanctuary and its often-targeted inhabitants.

Volunteers may ascend to the heavens and man the tower or simply come for landscape views.

Verified Threats are loudly alerted, and if they are not detected as “averted” within a certain time frame, will have a queer watch party and/or trained outside authorities called to the situation.

For example (at right): verified threats have been alerted at approximately 2:22pm. Two figures recognized as past defacement offenders with the other figure confirmed to be a serial verbal offender.

subverted song: tower protection

Calling back to the “beacon,” I wanted to signal how an iconic element, which is also the most vertical and by extent visible beyond the site, can be used and/or subverted: the bell tower.

I imagine the tower to operate as a kind of control tower and viewpoint, in which the oppressed population may begin to subvert surveilance tactics on harmful bigots who have no intention to engage peacefully or make conversation. It is important to note that the tower is not intended for permanent surveillance, but rather reacts to the temporal realities of the social landscape.

In time, the bells may toll songs and not sirens.

At left, two volunteers man the system and take note of suspicious activity in the landscape. Once the suspicions are confirmed as threats, an audible alert is sent and data is taken for future protection against repeat offenders to the sanctuary.

Existing: identify population, need, social norms, and infrastructures

Site Acquisition: subvert the project pitch to sanctified norms in design representation

Sanctuary: safe space for fluid uses of celebration and sanctification

Monastery: social space for disaster response, social relief, hybrid housing, and food services

Armory: node + network center for queer design and defense

Queerscapes: begin to filter + defend using queer landscape devices

Conclusion: begin the process of celebration, sanctification, design, and defense

Operation: safeguard campus + give community tools to collaborately defend until collaborative efforts deem protection less neccessary

a need may turn into a concerted effort to make tangible change for queer populations. As in any community, rumors are bound to spread. Target populations may begin to take note. As programs get up and running, word is spread and protection must begin. Once the armory is constructed, a larger network may emerge. The landscape becomes its own kind of ally, as well, and the complete processes of the proposal may begin to work holistically.

This timeline is what inspired the start of the final presentation, in which I “presented,” or “performed,” the project as if I were pitching the proposal as a literal church using only architectural conventions and coded design.

SECRETIVE reclamation

COVERT subversion of policy

OVERT subversion of space

DEFENSIVE reclamation

presentation critique

I used coded forms and architectural norms as if the final jury were the “board,” and the gradient of covert versus overt was at its most extreme. If the legislative agendas of Mississippi, the quantitative mapping relating to the larger region, and the documented queer experiences of the city of Jackson are any indication, this subversive pitch strategy is crucial to the viability of this proposal having any chance at being built and helping queer folk in the city and satellite small towns.

In order to get this kind of affront built, albeit as a theoretical suggestion, the subversion must extend to policy.

In the beginning “realistic” renderings, I only showed those parts of the project that were visible to everyone, or the “everyman.” The 20 seconds of excruciating silence, after the conventional plans and renderings were presented and I ceased speaking, were effective according to the jury, who were understandably worried after the pause. By presenting the project in this way, as “fakeout,” the critique effectively extends to all levels of architectural design and representation.

In terms of renderings, this one has a signal as well; the man in higher definition at center is one of those unknowing “passerby,” while the two shrouded figures behind his view are “in the know.” A community member points out the secret entry to a new sanctuary attendee.

I used this image as the “last slide” of the first presentation—the pivot point between the narrative—because it is the exact pivot point of entry in the project.

Once we pass through the filter and into the interior, the sanctuary comes into focus. Though it can be serene, the space can change aesthetics for a lecture or event, or even a rave when the pit can be used to full effect.

In the interior of the armory, light, shadow and filtering take on new meaning. An aquatic shimmering is filtered in through hover baths, while fortified wall punches give serial sifting. As for the people in the armory itself, specifically ones occupying the work spaces on the first level, they are elected democratically as part of the sanctuary community and work together, multi-inter-transdisciplinarily, to collaboratively enact change in the vein of design dispersion. There can be traveling plant events, live entertainment, academic lectures…

The pleasure gardens act as a kind of intermediary negotiation between the complicated binaries of internal/external and exclusive/inclusive.

The spaces here can be used for communicating, luxuriating, or loving. This exterior space can also at times be open to LGBTQ allies, so that they may support and enjoy the proposal without infringing on a sacred safe space.

The gardens can accommodate multiple agendas at once. A picnic and a reunion, for example, call for gradients of privacy. It’s not and/or, but both/and. The turning point from monastery to armory, pictured below, turns the corner both literally and figuratively from safe haven to defensive centre. The juncture of soft/ hard, sanctity/self, and community/ curvilinearity highlight the embedded embraces of the project.

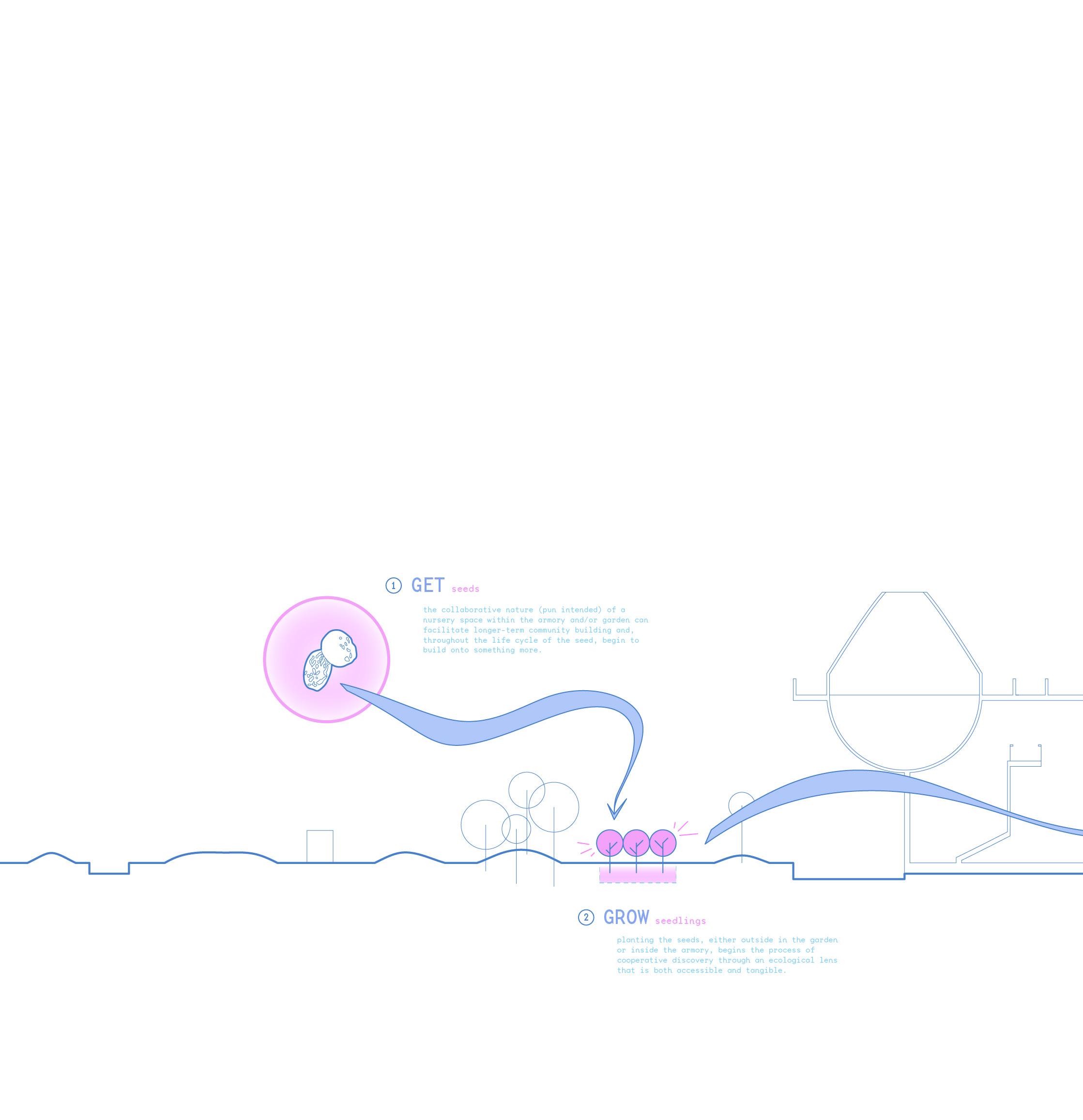

I’ll end here with a theoretical “design” use of the armory that engages a transdisciplinary kind of queering. You can trace “the life cycle of a seed” in the previous diagram through four major steps: GET, GROW, GIVE, and GROW again.

In this example, the armory for design and defense is adopting a nonbinary “both/and” strategy; the designs here can be ecological, architectural, sociological… and begin building a coded network of safe spaces or rendezvous points that ripple far beyond the site.

In this way, one can trace the life of a single seed through many hands, places, and processes until it finds its way home. In this example, an ornamental planting such as a cherry blossom tree can become a coded signal—perhaps even monument—for community, companionship, and safety beyond any singular safe site.

GET seeds

the collaborative nature (pun intended) of a nursery space within the armory and/or garden facilitate longer-term community building and, throughout the life cycle on to build onto something more.

GROW seedlings

planting the seeds, either outside in the garden or inside the armory, begins the process of cooperative discovery through an ecolo ns that is both accessible and tangible.

GIVE plants

a crucial aspect of the seed’s trajectory comes in a moment of exchange; here the seed travels beyond the nursery space out into the world to queer folk/ allies, beginning the network.

GROW coded networks

once the planting is transplanted to another site, those “in the know” may utilize it as a rendezvous point, coded signal of safety, or any other form of as grown physically logically into something much larger.

Will you meet me under the cherry blossom tree?

Bell, David & Valentine, Gill. Mapping Desire: Geographies of Sexualities, Routledge: 1st ed, 26

Brown, Michael & Knopp, Larry. “Queering the Map: The Productive Tensions of Colliding Epistemologies,” Annals of the Association of

Bruni, Frank .“The Worst (and Best) Places to Be Gay in America,” The New York Times: Opinion,

Campbell, Larrison. “Why I Moved My Family from L.A. to Jackson, Mississippi,” Architectural Digest,

Chauncey, George. “Privacy Could Only Be Had in Public: Gay Uses of the Streets,” from Stud: Architectures of Masculinity (p. 224), New York :

Choi, Esther & Trotter, Marrikka . Architecture at the Edge of Everything Else, The MIT Press, 2010.

Davis, Tim. “The Diversity of Queer Politics and the Redefinition of Sexual Identity and Community in Urban Space,” from Mapping Desire: Geographies of Sexualities, ed. David Bell & Gil Valentine, 1995.

Flucker, Turry and Hamilton, Anna and Hudson, Kate; advisors Andy Harper, John T. Edge, “The Farish Street Project: What happened to the “black Mecca’ of Mississippi?” Ole Miss, 2014.

Garner, Glenn. “The Queer Oasis of Jackson, Mississippi’s Lone Gay Bar,” Out, 4 September 2019.

Haferd, Jerome. “An Archeology Of Architecture: The Harlem African Burial Ground,” Log 48: Expanding Modes of Practice, Win/Spr 2020.

Hensley, Erica. “‘What happened to Farish Street?’: Accounting for millions of dollars, opportunities lost in a historic Jackson community,” Mississippi

Joseph, Lauren (Stony Brook University). “Finding Space Beyond Variables: An Analytical Review of Urban Space and Social Inequalities,” Spaces for Difference: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Volume 1,

Kempf, Petra. “You are the City,” lecture at Studio-X Rio, 28 March 2016. [https://www.youtube.com/

Kosofsky Sedgwick, Eve. Tendencies, Duke

LaRochelle, Lucas. “Queering the Map,” Queering the Map, ongoing [http://lucaslarochelle.com/

Ngozi Adichie, Chimamanda. “The Danger of a

Nicole, Sharie. “How OWN reality star, Jackson entrepreneur is ‘buying a block,’ revitalizing Farish St.,” WLBT News, 5 February 2021.

Ohrt, Roberto. “In the Passage of a Few People Through a Rather Brief Moment in Time: The Situationist International 1956-1972,” Branka Bogdanov, 1989.

Oren Smith, Zachary. “Queer love and struggle in Jackson, Mississippi,” Scalawag, 15 April 2019. Pavka, Evan. “What Do We Mean By Queer Space?” Azure, 29 June 2020.

Rosenberg, Matt. “The Bible Belt Extends Throughout the American South,” Thought Co, upd. 28 January 2020.

Samee Ali, Safia. “Jackson, Mississippi, water crisis brings to light long- standing problems in city,” NBC News, 2021.

Sheppard, Lola. “From Site to Territory,” Bracket: Goes Soft, 2012.

Sonnekus, Theo. “The queering of space: Investigating spatial manifestations of homosexuality in De Waterkant, Cape Town,” Taylor & Francis, 24 May 2017.

Tattelman, Ira. “Stud: Architectures of Masculinity by Joel Sanders; Mapping Desire by David Bell; Gill Valentine - Review,” Journal of Architectural Education, Vol. 51, No. 2, pp. 136-138, November 1997.

The State of California. “Prohibition on StateFunded and State- Sponsored Travel to States with Discriminatory Laws,” Assembly Bill no. 1887, 2016.

Thomas, Kate. “Lesbian Arcadia: Desire and Design in the Fin-de- Siècle Garden,” Lecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, 18 February 2021.

Video

“Jackson | Black Owned,” Square. (via YouTube, 17 January 2021) [https://youtu.be/xz8loUhQysI]

“City leaders speak out about Farish Street Project,” 16 WAPT News Jackson. (via YouTube, 15 October 2013) [https://youtu.be/_ Y6vGP2N3hs]”

Image Citations

Tanner Vargas, Scattered Sanctity, 2021, digital image, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Tanner Vargas, Shimmerplan, 2021, digital drawing, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Rozana Montiel (photo by Jaime Navarro), Fresnillo Playground, 2018, photograph (ed. Tanner Vargas).

Tuca Vieira, Paraisópolis, 2004, photograph (ed. Tanner Vargas).

Thierry Chesnot/Getty Images (from The Maison Margiela Fall 2018 Artisanal runway), 2018, photograph.

Tanner Vargas, Umbrellas, 2020, digital diagram.

Chris Hadfield, US-Mexico Border From Space (“Same land, different politics.” - from Twitter), May 8, 2013, photograph.

Teddy Cruz & Fonna Forman, Conflict Map, 2016, digital drawing, UIC Barcelona.

Eds. Esther Choi & Marrikka Trotter, Architecture at the Edge of Everything Else, 2010, book [The MIT Press].

Author Unknown, Vauxhall Gardens Map 1844-49, 1848, map.

Edward G. Lawson, The Villa Gamberaia, Settingnano, circa 1917, watercolor illustration.

Edmond Paulin, The Baths of Diocletian, 1880, watercolor.

Gerald Hannon (courtesy of Pride Toronto & the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives), Gay Rights Demonstration, 1981, photograph.

SOPHIE, “It’s Okay to Cry,” from Oil of Every Pearl’s Un-Insides, 2017, music video still.

Alex Garland, The Shimmer (from Annihilation), 2018, film still.

Tanner Vargas, SOPHIE I, 2020, digital image.

Tanner Vargas, Mapping the Queer Experience Across the United States (gathered from the Human Rights Campaign), 2021.

Lucas LaRochelle, Queering the Map, 2017-present, interactive digital mapping archive still capture [https://www. queeringthemap.com/].

Charles C. Mosley, Jr., Farish Street March 17, 1947 (courtesy of the Farish Street Project), 1947, photograph.

Google Earth, Farish Street Historic District (north end), maps capture, cap. 2019, acc. 2021.