TAKEOFF TAKEOFF

#2/FEB/2021

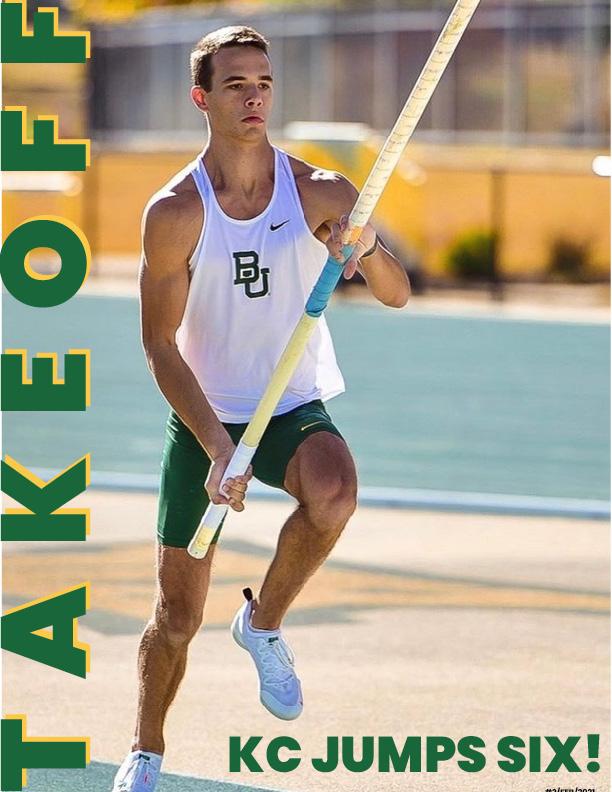

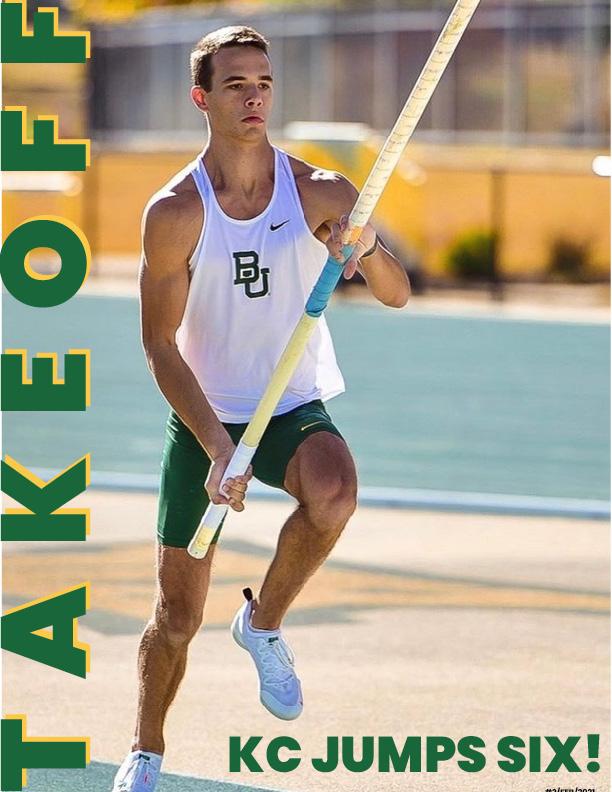

KC JUMPS SIX!

The mission of TAKEOFF Magazine is to inspire amateur athletes to personal greatness.

My name is Adele San Miguel, and I am the co-founder of Pole Vault Carolina, a training facility based in Durham, North Carolina.

TAKEOFF is the next iteration of our club’s mission: to coach the athlete to their highest self. I’m thrilled to have you on our runway.

ADELE SAN MIGUEL, PUBLISHER + EDITOR

TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

HELLO THERE!

We are pleased to be back with you for another issue of TAKEOFF!

Coaches and meet administrators are providing an essential physical and emotional safety valve for athletes during the pandemic: practices and competitions. Track and field is an island of encouragement in a sea of uncertainty. May we continue to work together to keep our youth healthy and whole.

Charles Oliver, CEO of Coach O Enterprises and the National Chairman of the Amateur Athletic Union says Covid-19 is a detour that athletes can choose to take. To read about how these two organizations are moving the sport forward, turn to page 12.

Wellness coach Emily Perrin teaches what she herself needed to learn the mosthow to quiet the inner critic. Advice from Emily is on page 22.

College professor and masters vaulter Ralph Hardy brings us the electric story of KC Lightfoot, his 6 meter jump, and capture of the NCAA indoor record three times in the last several weeks. Inspiration on page 26!

And do not miss Ralph’s warm, funny essay, Meditations on Pole Vaulting at 60 on page 16.

In Recruited, Kreager Taber highlights Carson Lenser, a high school senior from the Arkansas Vault Club who has committed to the University of South Carolina, page 14.

Have you visited The Olympic Training Center in Chula Vista, California? Team USA decathlete Harrison Williams will show you around on a typical Monday, page 30.

Want to view a jump through the eyes of elite coach David Alan Butler? Click to Coach’s Critique on pg. 42. If you have not picked up David’s book: Pole Vault: A Violent Ballet, see the ad on page 21 for details on how to order.

In If I Knew Then, 2016 Puerto Rican Olympian Diamara Planell Cruz shares the importance of not losing sight of your why. Page 46.

This, and much more! Your feedback is valuable as we move forward with the intention of educating, entertaining, and inspiring athletes.

All the Very Best, Adele

A

HTAKEOFF MAGAZINE 3

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Nearly double the content this issue! You will read about Baylor Bear KC Lightfoot and his meteoric season; hear from Olympian Diamara Planell, and view the analysis of a jump from coach David Butler. ON DECK Letter from The Editor 3 Makes and Misses 6 ClubHub 8 Championing Athletes, Charles Oliver of Coach O Enterprises 12 Recruited: Carson Lenser, University of South Carolina 14 Meditations on Pole Vaulting at 60 16 Perfection: Fuel for the Inner Critic 22 KC at the Vault: The Story of KC Lightfoot 26 A Day in The Life at The Olympic Training Center 30 Destination: Tokyo - Austin Miller and Alina McDonald 34 Coach’s Critique - David Butler 42 If I Knew Then with Olympian Diamara Planell 46 Cover photo credit: Temple Star Photography

David Butler

Pole Vault Zenmaster Rice University Coach

Author

Coach’s Critique

Sarah Elliott

Artist Student Activist

Back cover art. Prints available upon request at www.sarahelliott.com

CONTRIBUTORS

Ralph Hardy

Playright Novelist, Argos Masters Pole Vaulter

KC Lightfoot, Meditations on Pole Vault at 60

Emily Perrin

Wellness Coach CEO

Yogi

Perfection - Fuel for the Inner Critic

Diamara Planell Cruz

2016 Olympian, Puerto Rico 4x All American, University of Washington

2021 Olympic Hopeful

If I Knew Then...

Head Coach of Pole Vault Carolina

Makes & Misses, graphic design

Kreager Taber

Scientist Writer Pole Vault Aficionado

Carson Lenser

Harrison Williams

Team USA Decathlete

6X All American, Stanford University

2021 Olympic Hopeful

A Day in the Life

Jose R. San Miguel

MAKES & MISSES

By Jose R. San Miguel

What’s wrong with being a beginner?

As kids, we attend school and learn from a curriculum. Our minds are open. Some of us get it sooner than others, but for the most part, we all digest the material and move on to the next level. We master basic addition and eventually get to calculus.

We begin careers based on our knowledge and interests, and permit ourselves to be new, to perform with confidence and consistency, and get promoted to more challenging, rewarding roles. If you aspire to be a doctor, you attend medical school after college; do a clinical rotation; become a surgeon, and then a brain surgeon. It is a process, and you trust the process.

It is not always the same in athletics.

As young athletes start in sports, the initial expectation is that they will learn in a fun environment. They mature, and the competitiveness of their sport and society’s expectation kick in. The focus shifts from enjoyment to performance. To wit, to win. Unlike school, in which students are propelled forward toward a degree, in sports many are left behind, physically and emotionally, for not ‘getting it’ fast enough.

The emotional side of not catching on quickly can handicap you if you let it. It beats the human spirit and drains the self confidence.

Enter pole vault. Everyone gets to carry a pole, run down the runway and take a jump. There are no benchwarmers. Every athlete is afforded the chance to improve, something that is true across track and field at the club level.

As coaches, our goal should always be to lift the emotional well-being of every athlete who walks onto the runway, and teach them the skills necessary to create their own greatness, whatever that may be. This includes the super stars who on day one show potential to be the next state champion, to the scrawny, slow, uncoordinated kid who has been told in every sport that they are not good enough, but looks at you as if you are holding the last life preserver to keep them emotionally afloat.

The latter group are surprised that you give them the opportunity and support to excel. Several of our athletes who have made it into collegiate athletics came to us defeated by the system, with no basic athletic skills and the emotional baggage of being told too many times that they were lacking.

Every ending - cut from their last team, told they have grown too tall

Every ending - cut from their last team, told they have grown too tall to continue in gymnastics - is a new beginning in track and field.

6 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

to continue in gymnastics - is a new beginning in track and field.

As a pole vaulter, beginning is a constant. You master one drill or piece of technique, only to be daunted by learning the next. As your jump comes together, you PR, and get caught up focusing on that next height instead of focusing on improving the fundamentals, which will lead you to the higher bar.

At Pole Vault Carolina, we have participants pole vaulting for the first time. Middle schoolers, high schoolers, state champions, collegiate and post collegiate athletes, and currently, an Olympian work on bettering their skills to reach the next height. They line up beside one another on the runway, each working on their own specific area of improvement. We teach our athletes to be patient in their development and manage their expectations; to persevere mastering one skill, and then start working on the next.

If you are struggling in one area, try something new in another. Defeated by the Bubka drill? Go home and sketch what it should look like. Where should your elbows and hips be in full inversion? Focus on a creative endeavor and take the pressure off of practice. Your track life does not exist in a silo.

Stay curious. Asking yourself, I wonder what will happen to my jump when I work on my speed feels better than listening to the reel of WHEN am I going to PR again? running through your head.

Figuring things out has a pattern: it’s hard, it’s hard, it’s hard; and then it’s easy. As soon as you give that next PR breathing room, it will happen.

If you deny yourself the time and space to just be where you are,

you will impede your progress. Remain open, humble.

If you allow yourself to begin again, (and again) you may over time just find yourself in a place of mastery.

TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

7

Photo credit: Pole Vault Carolina

Austin, Texas

Owner and Head Coach: Ben Ploetz Coach: Brain Elmore

Austin Pole Vault and Throws Club Jack Mann

Jack is a junior at Lake Travis High School in Austin, TX. He began pole vaulting in 7th grade by chance, when the track coaches at his middle school encouraged him to try field events. In the fall of 2017, he met coach Brian Elmore. Today Jack credits Brian’s coaching with much of his own success. In 2018, Jack followed Brian to Austin Pole Vault and Throws, where he currently trains. Jack loves the sport because everyone is supportive and nice. Athletes, coaches, and parents alike are encouraging. Covid-19 has made going to practice special. He’s thankful for the opportunity to train and is looking forward to the 2021 outdoor season.

At the 2018 Pole Vault Expo, Jack triple PR’d winning his flight and realized his potential. Making the commitment to train year round (only Sundays during football season), he continues to reach new heights with each competition. In 2018, he finished 2nd in the 13-14 USATF Junior Olympics. At the age of 14, his freshman year, he cleared 14’0 to win his 6A District Championship and continued on through the Area Meet and Regional Meet. That summer, he won the 15-16 AAU Junior Olympics, his proudest accomplishment in vaulting! His sophomore year he broke his high school’s 20 year-old record clearing 15’8”. Last summer he won the 15-16 AAU National Championship.

Jack’s current indoor PR is 15’9” and outdoor PR is 15’8”. He is driven by the desire to vault his age and

higher. He strives for consistency and believes his successes come from patience, commitment, and hard work. Jack knows success comes if you invest in yourself and trust your coaches. Traveling for Jack’s competitions has become a family affair. Outside of pole vaulting, he is committed to his studies, philanthropies, friendships and family. Jack is a member of the NHS and Young Men’s Service League.

8 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

Photo courtesy of John Mann

Emily Fitzsimmons

Emily is a Junior at Lake Travis High School in Austin, Texas. Emily was a gymnast before she started pole vaulting during her 8th grade track season. With no pole vault experience, she won her first meet. Emily split her sports between pole vault, sprints and acro/tumbling gymnastics.

As a freshman, she joined Austin Pole Vault and Throws and thrived. She improved her PR from 8’6” to 13’0” (wow!), making her one of the top junior high school vaulters nationally.

Although her 2020 season was cut short, Emily competed at the 2020 AAU National Championships earning All American status. During the off season, she combined pole vault training with fitness workouts. She kicked off 2021 with a jump of 3.85m at Expo Explosion in Texas.

From a young age, Emily gained a lot of experience as a competitive athlete. She qualified for states 4 times as a Junior Olympic Gymnast. Emily is a Junior Olympic Acro National Champion and has performed at a Spurs vs. Warriors NBA game with her acro team.

Emily is a high achieving student and member of her schools’ Red Cross Club, Student Council, and International Key Club. She also volunteers for her middle school coach, encouraging kids to give pole vault a try.

Emily is grateful that the Lake Travis School District offers pole vault and hopes to help grow the sport in her community. For Emily, APV is her second home. She has made friendships there that will last a lifetime. She enjoys the individual responsibilities that come with pole vaulting, as well as contributing to a team. Emily aspires to compete in college.

TAKEOFF MAGAZINE 9

Photo courtesy of John Mann

Pole Vault Carolina

Durham, NC

Owner and Head Coach: Jose R. San Miguel

Erin Mink

Erin Mink walked into a Beginner’s Clinic at Pole Vault Carolina early in her junior year at Orange High School. A tall gymnast with fantastic tumbling ability, she also has an impressive mark of 5’ in the high jump.

A tumbling routine gone wrong interrupted Erin’s quick progress in the vault. A broken elbow required reconstructive surgery. The return to pole vault was shaky. Erin knew she had the ability, but she was unable to trust herself to reach her potential. Then Covid-19 cancelled high school sports and with her club closed for 2.5 months, Erin had time to reflect and refocus but no place to train.

During the summer and fall of 2020, Erin allowed herself the opportunity to improve. With the support of her family, and a new found drive, Erin started attending practices with greater frequency. She remained coachable, and her progress quickly became apparent.

The statistics do not always tell the true story. At the start of her senior year, Erin’s PR was 8’6”. On October 30, she jumped 9’; on December 18 she jumped 9’6” and on December 30 she cleared 10’6” a 12” improvement from her one week-old best. And, she nearly surpassed 11’.

Erin has done an incredible amount of technical work to generate improvement. But her

greatest accomplishment is staying with pole vault long enough for her latent confidence to emerge. Off the runway, you might mistake her for being quiet or shy; but Erin steps on the runway with purpose. It is there that her true nature shines through.

Erin is far from reaching her potential. If she tackles life as she has pole vault, there is no doubt she will make amazing contributions!

10 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

Photo credit: Pole Vault Carolina

Leah Schwagerl

PERSISTENCE is Leah Schwagerl’s middle name.

In high school, Leah competed in the 200m, 200m relay, 400m, and 400m relay. She started vaulting as a junior, and pole vault quickly became her favorite event. Traveling two hours each way to train at Pole Vault Carolina, she also somehow managed to achieve platinum level in gymnastics.

Leah’s high school did not offer indoor track so she competed unattached her senior year, jumping a PR at a collegiate meet in Virginia. She knew the height needed to become a walk on at UNC Chapel Hill, and dedicated herself to reaching it. But when sports went on hold last spring, the possibility vanished.

Staying positive, Leah developed a plan to ask the track coach for an opportunity to play. No scholarship, just a chance to practice with the team. That hope was dashed as days into her freshman year, UNC shut down.

Regrouping, Leah decided to compete unattached in college meets in 2021, but those meets too have been cancelled, or do not allow unattached athletes.

Attending our first home meet of 2021, Leah found some inner boldness, and opened at her PR. She cleared it on her first try. After her second miss, at the next height, she felt the familiar rise of defeat.

Coach stopped her for a motivational chat before her last attempt. It began with, “This is your moment….” Leah dried up her tears, and took on the runway and the bar, easily clearing a new personal best.

Every PR is special, but some define an athlete. For those who knew Leah’s story, the moment was emotional. A young person who had dealt with disappointment and sacrifice finally had her personal victory.

Way to go, Leah!

Photo credit: Pole Vault Carolina

TAKEOFF MAGAZINE 11

Coach O: Championing Athletes

By Adele San Miguel

By Adele San Miguel

Do You Know Coach O?

You have registered for meets using the software his company developed. You may be wearing a singlet or carrying a track bag designed by his team. The top-notch officials at your conference championship and NCAA regional meet? Hired by Coach O.

Charles Oliver is the CEO and founder of Coach O Enterprises, a company that serves track and field in three ways: Bags by Coach O, Coach O Registration, and Coach O Event Management. He is also the National Chairman of the Amateur Athletic Union and for the last eleven years, has served as the Meet Director for the AAU Junior Olympic Games.

You will be hard pressed to find an area of track and field that Coach O has not touched and improved.

Charles started in track and field as a senior at Jordan High School in Columbus, GA, where his record in the 400 meters still stands. He attended Troy University where he earned All-American status. An Olympic trials finalist in 1980, he returned to Troy to coach, and then moved to the University of Tennessee where he coached sprints, hurdles, long and triple jump from 1989 to 2009.

At UT, one of his areas of responsibility in Spring Sports Event Manag-

ament, was to negotiate contracts, reserve facilities, and work with partnering organizations like the SEC, NCAA, and AAU for the championship meets. When the position of AAU Junior Olympic Games Meet Director became available, the organization asked Coach O if he wanted the job.

Upon accepting, Charles stood back to view track and field from a wider vantage point. What is the experience of a meet for the 5 year-old athlete and that athlete’s parents? How will the hosting facility define a successful event? Meets can be long, hot, grueling days. How could it be an adventure and not an ordeal?`

Referring to the quote, “If you build it, they will come,” from the movie Field of Dreams, Coach O says they will not come if they do not know about it. He took a holistic approach. Instead of just filling spots on a roster, Coach aimed to deliver a product that serves. Sports teach. They instruct focus, task-orientation, how to stay motivated, deal with adversity, and get along. In youth athletics it is less about becoming the national champion, and more about learning to give your all.

The philosophy yielded results. With numbers growing exponentially every year, the AAU is having a positive influence on more children across the country. Of all the sports

TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

under the AAU umbrella, track and field is one of the largest. With Coach O’s guidance, attendance at the AAU Junior Olympic Games has swelled to 13,000 athletes. It is the largest youth meet in the world.

At the event, you will not find Coach O in the announcer’s box. He is on the field encouraging young athletes, interviewing them so they can practice public speaking, and growing them in confidence.

Registration 2.0

Registering thousands of athletes by hand for a meet was an enormous, expensive task requiring hours of tedious paperwork. Coach O contemplated an easier way.

He partnered with a friend to create a computer program for meet management. It was beta tested at the AAU Junior Olympic Games in 2000. Meet registration was carried out both manually and electronically. The results were within 100% accuracy. That effort birthed Coach O Registration, and the AAU became the first customer. This business vertical grew quickly, requiring its own set of employees.

Coach O Event Management emerged 8 years later. As a coach at UT, one of Charles’ area of responsibility was managing the meets. Tennessee hosted the majors, the SEC and NCAA Championships. Everyone assumed he was responsible for running all the events at Tennessee, even though at the time he was not. Informally, Charles advised other schools on successful meet management. He enjoyed it immensely, seeing many people he knew.

As he built his brand and trust with institutions, it was not without challenge. When the University of Louisville asked Coach O to manage

the NCAA Regional Championships at their campus, they endeavored to be excellent hosts and wanted a first class event. They agreed to everything he asked for, but balked at his request for a stipend for the officials. In a group call with all the schools hosting the NCAA regional meets that year, Louisville asked the question about the stipend. The other schools confirmed that they paid their officials and ran their meets exactly as they had learned from Coach Oliver.

The overarching goal of Coach O Enterprises is to promote positivity in track and field. Coach Oliver’s wife, two sons and daughter-in-law are involved in various aspects of the business. A staff is in place to post affirming content on social media, communicating high ideals and showcasing athletes.

A Bend in the Road

When Covid 19 closed down track and field, Coach O Enterprises and the AAU regrouped. They considered how they could safely hold competitions while adhering to federal, state, and local guidelines. Athletes needed the chance to compete. They increased attendance at the AAU Junior Olympic Games so more juniors and seniors could post a needed mark to attract recruitment.

Coach O Event Management partnered with Mondo Worldwide and produced webinars on host-

ing healthy competitions. Working through the details of which products to use to sanitize equipment, they also discussed how to stay on schedule and still make the event an uplifting experience. Several countries participated, including university head coaches and directors of operations. On the subject of how to bring the sport back, Coach O educated and led.

For hopeful recruits at this point in time, Coach recommends getting comfortable being uncomfortable. Covid is a detour; take the detour. Listen to those in the industry. Stay focused. Learn to trust yourself in the midst of change. There will be new ways to do things. Let them unfold, but don’t quit.

A bend in the road is not the end of the road unless you fail to make the turn.

Ultimately, Coach O’s philosophy and marketing strategy can be honed down to one word: care. Care about making track and field more accessible to more families. Care about making the meet experience easier for the hosting facility. Help people go after their dreams and goals. Promote the sport and put the athletes and their families at the forefront of it. Make it easy and move the sport forward.

And if you can’t figure it out at first, keep trying. Do it wrong until you can do it right, but do something.

Quentin Smith with Coach O.

TAKEOFF MAGAZINE 13

Photo Credits: Eric Ward

RECRUITED

Carson Lenser University of South Carolina

By Kreager Taber

By Kreager Taber

14 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

Photo provided

Carson Lenser’s athletic career began early. He learned to do gymnastics and play football, basketball, and baseball as a child. After taking part in track and field in middle school, his gymnastics background came in handy when he tried pole vaulting in eighth grade. Carson originally thought vaulting looked easy. But after clearing 9’ in his first competition, he was frustrated that it did not come naturally. He trained harder, realizing that there was always something that could be worked on and improved.

Later that year, Carson competed in his first national competition, the USATF National Junior Olympic Championships in Topeka, Kansas. He arrived at the meet with a personal best of 10’6” but the inspiration that he felt from the event, combined with adrenaline, pushed him to a new personal best of 12’7.5”. He tied for second place, fell in love with pole vault, and glimpsed himself competing in college.

That competition instilled a deep motivation to make his new dream of competing a reality. As a freshman in high school, Carson stopped training for other sports to focus full time on track and field. He sought out Coaches Morrey Sanders and Steve Irwin at the Arkansas Vault Club and began practicing with them two days per week. Though the Arkansas Vault Club is a 2.5-hour drive from his home in Vilonia, he arrives at every practice ready to give his best. His attitude impressed his coaches, who now rave about his character and work ethic.

“He has been self-motivated since the day I met him in the 8th grade, and has always worked hard to improve his technique,” says Coach Sanders. “Carson pushes himself to rise to the competition and he has a great time doing it, even if he’s having an off day.”

The summer before his sophomore year of high school, Carson spent each day working to improve as an athlete and move closer to his goal of jumping in college. His hard work paid off, and in his next season, he took second at the Arkansas 5A/6A Indoor High School State Championships with a jump of 15 feet. He also won the 400 meters, propelling his team to win the indoor state championship title.

During his outdoor season, Coach Sanders remembers that Carson was ranked to finish second at the state meet, but no-heighted. Carson was devastated. Still, he pushed his team to another state championship by winning the 400 meters and anchoring the winning 4x400 meter relay team that night. These wins encouraged Carson to stay motivated and introduced him to college coaches.

In addition to the pole vault, the 4X400, and the 4X100, Carson has also competed as a decathlete. He placed third in the decathlon at the outdoor state meet in 2019.

Carson competed during the 2020 indoor season. He cleared 15’10” for seventh place at the 2020 UCS National Pole Vault Summit. Continuing to improve, he jumped a personal best of 16’6” at the Arkansas Vault Club Vertical Climb Pole Vault Meet in February. With this mark, he tied in national rankings with Clayton Simms of Louisiana, one of the top vaulters in the country who has since committed to the University of Kansas.

Carson also won the Arkansas 5A/6A Indoor High School State Championships. He vaulted in one outdoor competition before lockdowns meant to slow the spread of COVID-19 began, and outdoor sports seasons were cancelled.

Carson made the most of this time, traveling to private club meets at Mac Vault Academy in Texas and Bell Athletics in Jonesboro, Arkansas. After jumping a huge personal best of 17’ at a Bay Area Pole Vault Academy meet in Houston this past July, his dream of competing in college was within reach. In November of 2020, Carson committed to vault at the University of South Carolina.

As a senior, Carson is training hard to prepare himself. Though his school’s indoor season has been cancelled, Carson loves to travel for competitions.

Carson’s father Michael has been instrumental in his success. Himself an 800 meter and long-distance runner, he trained Carson in the sprints, making speed one of the strongest components of Carson’s vault. Carson is as fast from a 12-step as he is from a 16-step. Carson shares his personal success with his whole family, who have supported him throughout his career.

Off the runway, Carson likes to hang out with his friends, enjoy time on the lake, and speak with youth groups at different churches. Carson is currently attending in-person school at Vilonia High School and is enrolled in an honors medical program. Once a student at South Carolina, he is interested in studying either business with a focus in supply chain management, or medicine, specifically, nursing or athletic training.

Whatever he chooses, Carson’s faithful work ethic will help him become a successful student-athlete at South Carolina and continue to push him to new heights as a vaulter.

provided by Carson Lenser

TAKEOFF MAGAZINE 15

Meditations on Pole Vaulting at Sixty

By Ralph Hardy

“I have something I want to tell you two,” I said over dinner.

My seventeen-year-old daughter raised her eyebrows; my wife put down her fork.

“I’ve been thinking about this for a long time and...” I paused. “I want to try pole vaulting,” I said, finally.

“What?” my wife sputtered.

“I thought you were going to say something important,” my daughter remarked. “Like you guys were splitting up.”

“Well, it’s important to me. It’s just something I’ve always wanted to do. And I’ve found a nearby pole vaulting club. I emailed them and I’m signed up for a beginners class this Sunday. Besides, why would you think we’re splitting up?”

“I don’t know. A lot of my friends’ parents are doing it.”

“Well, we’re not.”

And so, a few days later, in May 2017, on my 57th birthday, I found myself standing behind a fourteen-yearold girl, each of us nervously clutching twelve foot fiberglass poles, waiting for our turn to attempt to pole vault over a bungee cord strung between the standards at the height of ten feet. Somehow I cleared it. My coach, Jose R. San Miguel, high fived me, and at that moment I realized I was hooked.

Although I have occasionally run races from 5k to half-marathons in distance and competed in a few sprint triathlons, the last time I competed in a track and field event was my sixth grade field day where I ran the 50-yard dash. I think I leaned for fourth, but that was almost fifty years ago, so I can’t be certain. Chronic but mild asthma and a limited attention span have always restricted my participation in the long distance running that most of my peers enjoy. Among my friends, most of whom are in their late fifties, along with my twin brother, there are Boston marathon qualifiers, avid cyclists with multiple century rides, masters swimmers, excellent tennis players, and Ironman competitors. None of us are golfers. Or admit to it.

I have spent many hours in gym weight rooms, and I finish each workout with multiple pull-ups and pushups. In college, I took a beginners gymnastics class and enjoyed the rings and the parallel bars. I mention this because many female pole vaulters come from a gym-

nastics background. I also began skydiving in college and continued to do so periodically for most of my twenties, but that is an expensive hobby, and when my good friend blew out his ankle on a bad landing, and over a decade a few acquaintances died while skydiving, that sport soured on me. I’ve also done flips from ten meter platforms and quarry cliffs. The point of recounting this is that it never occurred to me that I was either crazy or foolish to attempt pole vaulting at my age.

Pole vaulting is a confidence game. You can’t fake it, you can’t do it at half speed; you can’t quit halfway through without risking a hard, unpadded landing. You have to run as fast as you can for ten to forty yards and either commit to the jump or run through without planting. Having been a skydiver I know how to commit to a jump. We were never allowed to climb back in the Cessna if we got scared. At least I never did.

The pole vault is the most technical of all field events. As someone once said, ‘you’re running with a stick so you can jump over a stick.” That’s basically true, except to be successful, the vaulter must run as fast as possible on a narrow runway, with a stride that varies by less than a few inches, holding the pole at a high angle so that at the moment he or she dips the pole into the box, the left foot is leading and poised to push off. During the initial phase of the vault, the athlete must keep his

16 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

Katie Nageotte with Ralph Hardy at Pole Vault Carolina

Katie Nageotte with Ralph Hardy at Pole Vault Carolina

17 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

Photo credit: Ralph Hardy

arms extended, with a slight bend, and use his arms for leverage as he begins his kick or swing.

There are two schools of thought regarding the swing. The Petrov-Bubka method, which my coach endorses, directs the vaulter to keep the right leg bent at ninety degrees and kick up with the left leg only after the pole has loaded, adding additional energy to the recoil. When the left leg catches up to the right, the vaulter shoots both legs up, twists, and now fully upside down, pushes up and away from the pole, kipping over the bar. Bubka, of course, refers to the Ukrainian athlete Sergei Bubka, the greatest male pole vaulter of all time. Bubka set the world pole vault record 35 times, and it’s claimed he received financial bonuses for each world record, so he made sure to increase his records incrementally, centimeter by centimeter.

Alternatively, there is another popular swing approach called the tuck and shoot. This swing is accomplished by tucking both legs in toward the chest rather than leaving the trail leg extended. This method shortens the lower body about the rotational axis, making the swing faster, but lessening the pole-loading effect of the swing. Jeff Hartwig, an American pole vault deity, who is one of a handful of men to clear 6 meters in competition, and at age 40 vaulted 5.70 meters (18-8.24) at the Olympic trials in 2008, employs the tuck and shoot method, as does Olympic silver medalist Sandi Morris. Interestingly, Jeff Hartwig, like Sandi, is a snake collector.

Among my many technical errors in the vault, the one most difficult for me to overcome is climbing the pole. That is, I don’t always keep my arms extended when I plant; instead I sometimes pull the pole toward me as if I’m doing a chin-up

on it or climbing it. This, of course, prevents the pole from moving forward toward ninety degrees, which means that even if I successfully get my legs over my shoulders, when I release, I’m not very deep into the pit, risking landing on the box. At my club, nearly every jump is videotaped, so the evidence is there for me to see. So I practice by planting a pole over and over into the sliding box, flexing the pole and keeping my arms straight, hoping muscle memory will take over during the real vault. Sometimes it works.

Although I have primarily used the masculine pronoun for most of this essay, the women’s pole vault has become perhaps the most popular women’s track and field event. At Pole Vault Carolina, my coach has noted that his club has changed from one where only boys jumped to one where two thirds of his athletes are girls. The top female pros include Americans Katie Nageotte, Sandi Morris, and Jenn Suhr; Olympic gold medalist Katerina Stefanidi; Canadian Alysha Newman, and the Russian, but neutral athlete, Anzhelika Sidorova. Among them they inch closer and closer to consistent sixteen foot vaults, while cultivating throngs of fans.

The current women’s outdoor pole vault record is 5.06 meters (16f 7in) set by Yelena Isinbayeva in 2009 and the men’s record was, until recently, 6.16 meters, set by Renaud Lavillenie, a popular French athlete and motorcycle racing enthusiast. His top challengers have been two Polish vaulters and the American vaulter Sam Kendricks. Kendricks is clean cut, blond haired and blue- eyed, a lieutenant in the Army Reserves who famously interrupted an approach at the Olympics to stop and salute while the American national anthem played for another athlete. He was the 2017 world champion and won bronze at the 2016 Olympics. His PR

is 6.06 meters and he routinely exceeds 6 meters, the gold standard of men’s pole vault.

Then there is Armondo Duplantis, known simply and globally as Mondo. Mondo has a Swedish heptathlete mother, and a Cajun pole vaulting father, who built a pit in their backyard. Despite growing up in Louisiana, Mondo chose Swedish nationality when he began to compete internationally after a year at LSU where he set the collegiate indoor record. A YouTube sensation, Mondo has set word records at every age, and at nineteen, had already cleared 20 feet. Then, on February 8th of last year, Mondo set the world record, vaulting 6.17 meters (20ft, 2 inches) at an indoor meet in Poland. Watch it on YouTube and be astounded. That vault actually led ESPN’s top 10 Plays of the Day. A week later, he added another centimeter in Glasgow, with inches to spare. And, oh yeah, he had just turned twenty-one.

The pole vault evolved from the centuries-old practice of using poles to vault over canals and drainage ditches in the Netherlands and England rather than walking long distances to find bridges. In competition, distance pole vaulting was the norm, with height competitions not recorded in England until around 1843. Modern height vaulting was introduced in Germany in 1850, and the event was included in the first modern Olympic games in 1896. William Hoyt, an American, won gold with a vault of 3.3 meters, a pedestrian height these days. The event was expanded for women in 2000, with American Stacy Dragila winning gold with a vault of 4.6 meters.

Of course pole evolution has paved the way for significant increases in height. Vaulters historically used bamboo or aluminum poles, but beginning in the 1950s, fiberglass and

18 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

carbon designs allowed vaulters to flex the pole deeper, resulting in increased energy transfer, and greater heights. The current men’s world record of 6.18 meters is nearly 25% higher than the records from the 50s, a greater increase in performance than among nearly any Olympic discipline. My own goal, which I’ve never stated publicly, is four meters, or just over 13 feet.

The club where I train is called Pole Vault Carolina. Founded in 2015 by Jose R. San Miguel, a native of Puerto Rico and a former elite University of Tennessee pole vaulter, with six poles, ten athletes, and a 90-day indoor facility lease, Coach Jose has shepherded more than 30 athletes into college athletics, including his two eldest children, helping them attain hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of scholarships, as well as multiple state titles. His wife, Adele, nurtures the vaulters through college application anxiety, relationship issues, and the challenges that most teenagers face.

Sometimes before practice Coach Jose and I talk shop: pole vaulting luminaries, technical nuances, up and coming vaulters. “I hope all my athletes become students of the sport,” he tells me.“They have so many distractions. When I was a teenager I trained six days a week.” Soon the club fills with athletes: beginners and more advanced vaulters, two are masters vaulters who jumped in college. Coach Jose makes sure everyone knows each other; he’s trying to build the concept of a team around a highly individualized field event. He urges them not to run cross country in the fall. “No pole vaulter ever runs farther than they have to,” he tells them, laughing. “Run sprints, lift weights, walk on your hands.” After warm ups, he tells us what to focus on during the practice and then we line up for drills. Soon I’ve got my favorite pole in my hands and

chalk on my palms. A teenage vaulter has her playlist echoing through the training center and Coach Jose stands near the box, ready to “tap” a vaulter on the back as they begin their plant.

“Run fast, attack the box, and keep my arms straight,” I tell myself over and over. Sometimes it works.

On my drive home after practice, I pass under a number of bridges with their clearance heights listed. I once read on a pole vaulting forum that at some point in their careers every vaulter looks at these heights and thinks, “I could clear that.” One bridge I drive under after every practice shows 12’6”. I could clear that, I think. One day.

“Nice jump,” I tell the teenage boy who just finished a vault. And they are all teenagers, besides me, of course.

”Thank you, sir!” The boy responds. The vaulters at my club are all very polite, hardworking middle school and high school students. The older ones are knee deep in AP classes, college visits, and scholarship applications. They compete for their high schools in pole vault and train at Pole Vault Carolina. A busy Sunday morning practice typically sees 8-10 beginner vaulters and the afternoon practices will have ten to twelve advanced vaulters charging down the runway, vaulting over bungees set at three different heights, congratulating each other with choreographed handshakes. One high school senior solves Rubrik cubes while he waits his turn. Over the summer I saw a few of the kids go down with injuries: sprained ankles, shin splints, a torn thumb ligament, but these were teenagers; they healed quickly and came back strong.

I blame myself for my first major pole vault injury. I had trained all summer and my technique was slowly improving. It was early September and I

was determined to compete in an official meet in the fall, so I had begun practicing every Sunday. During the week I think I strained my bicep doing weighted pull-ups, and then on Sunday, powered by Advil I attended an early morning practice with just one other vaulter. As a result, I vaulted over and over, focusing on attacking the box and swinging hard.

The next day I had trouble lifting my right arm, and it throbbed as I wrote on my class whiteboard. But I had jumped well, overcoming a stride glitch, so I was anxious to return to practice. The following Sunday I again registered for the early morning session, and again, I vaulted over and over, ignoring the now burning pain in my shoulder. After practice I iced my shoulder, took more Advil, and said nothing to my wife. The next morning I couldn’t change the radio station in my car, and simply extending my right arm was nearly impossible. In class I scribbled a few notes on the whiteboard and showed a film. That afternoon I called an orthopedist. He saw me the next day and after a few questions, and after moving my arm several different directions and watching me wince in pain, he diagnosed a strained rotator cuff, with a possible tear.

“Let’s try six weeks of twice weekly PT and see if it improves,” he said. “The insurance companies like to see that before I schedule an MRI.”

Physical therapy, ice, and NSAIDs failed to alleviate the pain in my shoulder and my range of motion barely improved, so after six weeks my doctor ordered an MRI. It showed a complete tear of my supraspinatus, the large, medial ligament that comprises part of the rotator cuff, as well as a partially torn bicep. Surgery to reattach the tendon is the only treatment, so I scheduled the surgery for mid-December, after my classes ended. At my pre-op, my sur-

TAKEOFF MAGAZINE 45

geon raised his arm straight up over is head.

“This is the goal,” he said.

“No, “ I replied. “The goal is thirteen feet.”

“We’ll see, “ he laughed.

The surgery went reasonably well and PT started soon after. I attacked it hard, pushing myself to rebuild my strength and flexibility. But even with my hard work, rehabbing a rotator cuff takes months, sometimes a year. At ten months I begged my wife to let me jump again, promising to focus on drills, with a hard cap of five jumps per practice. Surprisingly, she agreed to let me go back. Soon I was regularly clearing eleven feet, and occasionally brushing the twelve foot bungee, my Everest, all while setting a limit on my attempts. By March, as I neared my 59th birthday, I was feeling a little cocky.

“You have a good swing,” Maddie said, looking at me. I turned around. No one was behind me.

“Me?” I asked.

“Yeah. You really swing up hard.”

“Thanks,” I said. “I’m not very limber so I just have to kick as hard as I can.”

Coming from one of the best jumpers in the state, that compliment stayed with me all through practice. What I lack in speed, I make up for in rigidity. The kids all stretch before and after practice, but my muscles and tendons have no give left. I’ve watched hours and hours of pole vault videos, and even at slow motion, at no point have I seen the need to be excessively limber, so I eschew the stretching for upside down pushups and hard kick ups on the rings.

Motivated by Maddie’s compliment, I cleared 11 feet on six straight jumps, from four lefts with a 12-foot practice pole and wearing running shoes. Four lefts means I was taking only eight steps, which limits my speed but increases my stride accuracy. Then I cleared 12 feet, just grazing the bungee. A bar would have stayed up, I told myself. Coach said I should move up to a longer pole or move back for a longer approach. I was jazzed. That was a Sunday in March. The next Wednesday I left to go skiing in Utah with my friend Mark, a cancer survivor. By noon on Thursday I was in an ER in Ogden, getting x-rayed for a broken left shoulder. Later they found I’d torn my rotator cuff, as well. The other one. I waited a few weeks until spring break so I wouldn’t have to cancel too many classes and then went under the scalpel again. When I’d used up my allotted visits at PT, I kept up my exercises at the gym, including hanging from a bar while my shoulder stretched and strengthened. Months passed and my pullup reps increased from three to five to fifteen, then twenty. But by then the ban was in place, imposed by my wife, who carries our health insurance. No more pole vaulting.

Until the recent decline in life expectancy among white males due primarily to opioids and suicides, what Case and Eaton called “deaths of despair,” demographers generally expected us boomers to live longer, healthier lives than our parents. We smoked less and exercised more. “Sixty was the new forty,” we all read, so more men my age competed in marathons and triathlons. We drank red wine for the reservatrol, not the buzz, and we watched three men over thirty dominate men’s tennis. Even Tiger, at forty, had tricks left in his bag. Still, there is a price to pay for our longevity. Jans Barr, one of the most prominent--and few--phi-

losophers on aging and gerontology argues that we face the prospect of extending lives but emptying them of meaning. But what gives life its meaning, particularly if, like me, you live a secular life? Where do we find virtue?

Having published a middle school novel on Odysseus in 2016, I dove back into Greek philosophy about the time that interest in stoicism began to surface. Suddenly the Greek philosophers like Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, Zeno, Cato, and Epictetus were back in vogue; their message of emotional resilience seemed to resonate in an age of polarization, anxiety, and depression. according to Epectetus, discerning what is in one’s control and what is not, leads to apatheia or equanimity. I can’t control the fact that I’m aging, but I can control my response to it, I told myself when I woke up stiff and sore from vault practice. The Greeks did not have NSAIDs, but I did.

I began this essay a year ago. At that time, a virus, no larger than 100 nanometers was replicating in respiratory tracts in Wuhan, China. Now it has spread across the globe, and more than 400,000 American have died. Vaccines are being administered. Normalcy, or some simulcrum of it, will return. A few of us will be wiser, more cautious.

Pole Vault Carolina reopened with an outdoor pit and mandatory masks. Coach Jose sends home workout regimens by mail. My shoulders are healing, but my foot speed diminsishes daily and the ban is still in place. I’ll soon be sixty-one. When the time comes, I will tell my wife that life is different now, we have all seen the end of our calendar, and so we must seize the moment. Thirteen feet still seems high, but attainable.

20

Author David Butler A new book about everything you want to know about the pole vault. To order, contact David at stavhop@comcast.net 713-417-1274 21 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

PERFECTION Fuel for the Inner Critic

By Emily Perrin Perrin Wellness and Performance

Perfect. The dictionary defines it as being without fault or defect. Flawless.

We live in a world where perfect is the expectation.

I spend most of my time working with collegiate and professional athletes. I confer with coaches about their teams. I watch practice, lift, training, and games. I observe, listen and analyze.

The language we use around sport is crucial. Words matter not only for how we communicate with others but with how we speak to ourselves. There is a constant dance of internal and external messaging.

Is the word perfect used frequently in a sport setting?

No. To be honest I don’t hear many players or coaches express needing things to be perfect. I hear the opposite.: “We can’t be perfect, I know I can’t be perfect, I don’t expect perfection in each performance.”

However, why does the fear of failure and making mistakes plague so many of our youth and collegiate athletes? Across the board imperfection and flaws are seen as not

okay. Let’s take something outside of sport - the beauty industry. Look at any social media platform and you will see women pumping ads about skin creams and laser treatments that get rid of flaws. We see fitstagrams talking about how to eliminate body fat and cellulite. There is a workout for how to eradicate almost any part of your body that you don’t like.

This is not an issue that is solely in sport and performance, but a larger issue that plagues our society as a whole.

For the vaulter, missing at a PR time and again, or going no height can touch a very sensitive piece of self worth. This issue can directly be linked to our value as a human.

In pole vaulting, the need to execute perfectly can lead to paralysis. It is easy to get fixated on one particular phase of the jump, or comparing ourselves to the next person in line who might be a teammate with more experience. Very quickly, the message or thought of “that jump wasn’t good” becomes “I am not good.”

It’s a confusing message when many of us know we can’t be perfect, our coaches say they don’t expect perfect

22 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

but at the same time, success in sport revolves around winning and being at a higher level than your opponent. This can be hard to navigate, especially when you don’t have the support and tools in place to help yourself out.

I was far from perfect. I have a long history of chronic anxiety, bouts of serious depression and panic attacks that landed me in the hospital. I coped with it in harmful ways such as self-mutilation, binge eating, and substance abuse. Although there were many contributors, at the core of my issues was the idea that I needed to be perfect in everything I did. I felt inherently not enough if I was not perfect even though I continued to fall short of my own expectation of perfect time after time. Perfection was still something I was always seeking.

And that is the problem with perfect. It is a destination, the end game, right?

For many elite athletes, perfection is what drives us. Again, we rarely use the word but isn’t this what many of us are thinking? The desire to hone our skill and be the best we can be? If we make a mistake, people hardly notice because we are really that good. When we are perfect, everything falls into place. If we are the best on the runway, we can attend the college program of our dreams and have athletic careers that will be remembered for years to come.

But at what cost?

Perfectionism is fuel for the fire. It makes for a nasty case of depending on external validation, which heats up and provokes our inner critic.

The inner critic is that voice inside our head that never shuts up. It is the voice of doubt, negativity, criticism. It is the driver of constant comparison and assessment. It is the feeling that we are never enough. The inner critic is persistent. Ugly. Loud.

Many athletes have the idea that the inner critic is what keeps them sharp. This is what allows us to see what we aren’t doing so that we can constantly get better. That’s the goal, right?

Wrong.

More often than not, the inner critic is not accurate. Many times it’s a dialogue that is false information doing more damage than good.

There is a difference between objectively looking at your performance, giving yourself (or getting) constructive feedback, and walking around with a constant narrative

about your flaws and faults.

Ok. So how do we find balance? What’s the magic trick?

There isn’t one but this is where I come in.

I’m not a sport psychologist. I’ve been an athlete and a coach my entire life but I didn’t go to school to study the psyche and sport performance. I landed on my trade by way of personal destruction and the dire need to heal. As I speak to more and more coaches and athletes, I realize that this is an all too common story.

My specialty is mindfulness. A practice and way of being that allows us to pay attention to our present moment experience with a non-judgmental attitude. We can train mindfulness in many ways. Some of my favorite ways to practice are meditation, breath work, and yoga. These practices allow us to drop into our mind and body and get curious about what we are experiencing in a way that is more neutral and friendly.

How does this help with perfectionism and that pesky inner critic?

It allows us time to watch our thoughts and put space between what we are thinking and how we respond to them. This is crucial. We can see the inner critic for what it really is and claim some power back.

Emily with Duke women’s soccer and men’s baseball.

TAKEOF F MAGAZINE 23

Photo credits: Emily Perrin

We do not have to BELIEVE everything we think. So the next time you notice your inner critic come around, try the following practice:

1. Notice - Notice what the inner critic is saying. What are you telling yourself about your performance?

2. Get curious - Ask yourself a question : Do I have evidence for this thought? Can I ask a teammate or coach if I am unsure? This way we help ourselves decipher “Is this actually true?” Remember - often times the inner critic is not true!

3. Take a Breath - Breathing is one of the most powerful things we can do when we are being hard on ourselves. It allows us to push the pause button. This can be helpful when we are going back and forth with the inner critic.

4. State something you know to be true . What is one thing that you know wholeheartedly to be true about yourself as a human being? Something that no one would debate or question? Tell yourself that. Build confidence in a quality that you know is valid about the kind of person and athlete you are.

In closing, I want to reiterate the definition of perfect, without fault or defect; flawless. It doesn’t exist. It is a destination that doesn’t exist in sport and performance nor in life. Unfortunately it’s not as easy as flipping a switch and not caring about perfection. We have to work at it. The practices of mindfulness, meditation, yoga, and breath work are tools. The next time you feel the paralysis of perfection and your inner critic is yammering, take it slowly. The journey to navigating your mind is a marathon, not a sprint.

24 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

Emily with Pole Vault Carolina

Distributor of New and Used Equipment Poles Mats Standards Hurdles (919) 523-8333 jose@polevaultcarolina.com 25 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

KC at the Vault

by Ralph Hardy

There are a few last names in athletics that aptly predict one’s success in the sport: Marina Stepanova in hurdles, Rollie Fingers and Prince Fielder in baseball, Gary Player in golf, Margaret Court in tennis; and of course Usain Bolt, the world’s fastest man. Add Lightfoot to that curious list, for that last name belongs to the NCAA Indoor record-holding pole vaulter KC Lightfoot.

On January 16, 2021, at an indoor meet at Texas Tech University, Baylor athlete Lightfoot cleared 5.94 meters (19”5.75”), surpassing Chris Nilsen’s record set last year, which supplanted the previous record set by Armond Duplantis. With a clean slate, KC went for the elusive 6 meters, a height he’s cleared in practice, but came up short three times. Still, he went home that night

with the NCAA Indoor record and the world lead. Two weeks later, he broke the record again with a vault of 5.95 meters, (19’6.25”). Six meters remained out of reach.

But on February 13, on a return trip to Lubbock for the Texas Tech Shootout, KC bested the indoor record again with a mighty six meter jump, positioning himself alongside Mondo and Renaud Lavillenie as the only three men in the world to clear six meters at this point in the season.

The 21-year-old Lightfoot grew up in Lee’s Summit, Missouri, playing a wide range of sports and spending weekends on a motocross bike. Baseball was a passion and he was good at it, but when he first picked up a pole at Just Vault, in Excelsior Springs, around thirteen, he

was quickly hooked on the sport. By sixteen he knew he had something, and so did his father, Anthony, who had been a vaulter in high school and college (4.90m). His son was a natural, and the heights increased quickly.

“I studied the sport,” Lightfoot says, like any serious athlete, watching YouTube videos of the French world record holder and Olympic champion Renaud Lavillenie and, later, his compatriot Sam Kendricks. And of course, Mondo, who is his peer. His last two years of high school are a blur of accomplishments: Missouri Boys Gatorade Track athlete of the year and two-time state champion in the pole vault; the Missouri all-time best and United States No. 2 jump in high school history; New Balance Nationals Outdoor

Cham-

Cham-

26 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

Photo credit: Baylor Bears

pion and meet record; first place at the Pole Vault Summit, third at U.S. Juniors; second at New Balance Indoor Nationals; second at Texas Relays, and 10th at the U.S. Indoor Championships-tenth, against the best adult pole vaulters in the country. A model of consistency, Lightfoot cleared 18 feet 12 times in 10 meets and finished high school with an astounding PR of 5.61m (18’5”). College coaches took notice and he received scholarship offers from a number of universities including Baylor, Kentucky, Washington State, Kansas, and South Dakota, all pole vaulting powerhouses. He chose Baylor for its strong track and field program led by coach Todd Harbour as well as its high academic standards. Moreover, Brandon Richards, Baylor volunteer assistant coach, had been a protégé of his club coach, ensuring a positive transition. Now, the 6’2 junior is at the top of his class and a three time All-American, with accolades and records as long as his favorite pole. Nineteen feet has become routine.

A kinesiology major, Lightfoot has to juggle a demanding academic schedule: biomechanics, anatomy,

nutrition, exercise physiology. He takes his classes in the mornings, grabs lunch, gets treatment, then has two or more hours of pole vault practice, followed by weight training three times a week. After dinner, there’s always homework. Rinse and repeat. And of course he has to travel to meets, which can last all weekend, so he does his schoolwork before he leaves. All the while aspiring to being not only the best collegiate vaulter, but to be among the world’s best at his sport. He’s already made one world team. He first competed for the U.S. in Belarus at the Europe vs USA meet a few weeks before the World Championships in 2019. He was a teenager training with and competing overseas against his more senior idols. Minsk is a long way from Missouri. He came in 6th with a clearance at 5.30m. Later, in Doha, he found himself warming up alongside the best in the world: Lavillenie, Kendricks, Lisek, Braz, Duplantis, and another American, Cole Walsh. Lightfoot cleared 5.60m, but missed qualifying for the finals by about 4 inches, and ultimately placed 15th. Kendricks won at 5.97m. According to KC, being a member of the World team ranks as one of

his greatest athletic highlights and proudest achievements.

Lightfoot has a deserved reputation as the Baylor track and field team daredevil. He bridge jumps, cliff dives, and skydives. It’s those precious seconds of freefalling--of weightlessness--that has him hooked. The same mental process that convinces him that he can jump out of an airplane at 10,000 feet allows him to stare down a nineteen-foot bar and believe he can clear it. And he usually does. Lightfoot considers his plant to be one of his strengths, which allows him to get on some big poles, relative to his weight. Perhaps landing a motocross bike thousands of times honed his aim, but he rarely blows through an approach. Watching videos, visualization, and trusting his training helps him cope with the mental aspect of the sport, which he admits can sometimes be overwhelming. Lost confidence has broken more than one elite pole vaulter, but KC trusts his process.

“There are always butterflies,” he says, despite the fact that in most collegiate competitions he’s jumping nearly a foot higher than his fellow vaulters. “It’s a solo sport, really. It’s you against the bar.”

Some vaulters obsess over their numbers, but not KC. “I feel that picking a specific number can lead to problems because if you do not hit that number you may feel disappointed, or if you hit the number too early then you may become satisfied and quit working as hard,” he says. “The numbers will come. It’s the process that matters and trying to get better every day.”

27 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

Photo credit: Baylor Bears

As with every other athlete, Covid-19 has impacted Lightfoot’s training.

Last year’s NCAA outdoor season was cancelled and there were no trips to Europe. Instead he returned home. His mother, Kim, was glad to have him back, and he spent more time with his siblings, Carli, Chuck, and Tanner. Some athletes might have slacked off without the watchful eye of a college coach, but KC didn’t. He returned to his home club and made the best of it. The shorter

runway there may have been an unexpected blessing. It forced him to focus on top end speed and technique. When you can clear 5.80m from six lefts, you know you have something in the tank, and he is proving it this season. It’s hard not to look ahead toward Tokyo, but the NCAA indoor and outdoor seasons remain his current focus. Then he’ll have the Olympic trials where Sam Kendricks and others will be vying for one of the three spots available. The Olympics themselves might

even be cancelled. But KC knows he can’t worry about that. You can only clear one bar at a time.

Despite the fact that he has jumped the world lead twice, KC says he doesn’t have a target on his back. Mondo and Renaud began their indoor seasons with world record jumps of 6.01m and 6.02m.

Still, the track and field world is paying attention to what’s happening down in Waco. KC is giving interviews on college radio stations. He was profiled in World Athletics. Pole vault fans-and there are more every day-are checking out KC on YouTube or following his meets online, refreshing their browsers, looking for the zeros that mark each clean jump.

Inside the frenetic, circus-like arenas of an indoor track meet, more eyes are turning to the pole vault. There, a slender, brown-haired young man in green and gold grabs his pole and stands, waiting. The other vaulters, many with three X’s already, watch expectantly. The clock ticks down. The arena grows silent. No one breathes. KC is at the vault.

28 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

Photo credit: DyeStat.com

Photo credit: Baylor Bears

+1 (434) 981 7387 emily@perrinwellnessperformance.com

29 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

Who We Work With

at the Olympic Training Center A Day in the Life

by Team USA Decathlete Harrison Williams

As a decathlete currently training at the Olympic Training Center in Chula Vista, CA, I am part of the residence program. USATF pays me to live in the dorms, eat at the dining hall, and prepare for the Olympics using the facilities. The OTC is a mini college campus for athletics. Everything you need to prepare for competition, including a track, weight room, dining hall, and training room, are within a 3-minute walk. What attracted me to live here was the ability to pretty much entirely focus on training. As you can see from my typical Monday schedule, this is probably one of the best places in the country to do so.

8:00 am Wake Up. I’ve had trouble sleeping for most of my life, but I’ve found that if I keep a consistent wake-up time, it’s a lot easier to fall asleep in the evening. Living at the OTC means I have a stable schedule each day, which makes it easier to keep a regular wake-up time. But it gets pretty tough to force myself to get up at 8:00 am on the weekends even though I have nothing to do those mornings.

8:30 am Breakfast at the Dining Hall. One of the biggest benefits of being on site at the OTC is having a dining hall only a short walk away. I usually stick to eggs, turkey bacon, and some oatmeal; nothing too heavy since I usually have training soon after.

8:45-10:00 am Hang Out. I like to have 1-2 hours after I eat to just hang out and let everything digest before practice. If I’m feeling particularly sore, I’ll do some light stretching to get ready for training. I don’t like to watch Netflix or play video games before practice because it distracts me, and I end up going into training with my mind somewhere else.

10:00-10:30 am Warm-Ups. The 30 minutes before practice is when I’ll do my event-specific pre-warmup routines. If it’s a hurdle day, I’ll grab my stretchy band and do some band distractions for my hip. If it’s a pole vault day, I’ll make sure to stretch out my hip flexor so I’m ready to hit some good positions at take off, and loosen up my shoulders a bit.

26 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE 30

TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

Photo credits: Trenten Merrill

10:30 am-1:00 pm Training Session #1. This is when we get all of our technical work in on the track. As a decathlete I’ve got 10 events to train for, so we usually practice 2 events per day. On Mondays, it’s shot put then sprints. On pole vault days, we practice a bit later in the day, around 1 pm, because there’s always a big tailwind in the afternoon, and we want to take advantage of that.

A quick note – My mentality towards training has shifted a lot in the last year. For most of college, I focused on trying to make big improvements every day. As a result, I never felt like I was improving. I left practice disappointed most of the time. Recently, I’ve been trying to hone in on making small gains at each session. I’m not only enjoying training more, but the progress is coming more quickly.

1:00-2:30 pm Lunch and Rest. This is when I really like having my living quarters, a dining hall, and the track all in the same place. I can finish practice, grab food fast, then relax in my room until it’s time to lift. The dining hall food is not the best in the world, but the convenience of not having to worry about going to the grocery store, cooking something, and then cleaning all the dishes makes it worth it.

After lunch I take time to write a few notes about how practice went and how my body felt in my training journal. Maintaining a journal is important as an athlete because it helps you observe specific cues that helped you improve technically. You can monitor how you felt throughout the workout. It’s great to have something you can look back at to follow your progress.

2:30-4:00 pm – Training Session #2 - Lift. We have a great weight room setup at the OTC. We lift 3 days per week at the moment - Monday, Tuesday, and Friday. I don’t know too much about weightlifting, but luckily we’ve got some awesome strength coaches here who

know what they’re doing. I do what they tell me. After we’re done lifting, I do core strengthening or pole vault-specific drills like Bubkas, rope climb, and hanging extensions.

4:00-6:00 pm Stretch and Mobility. This is a very important part of my day. If you don’t stretch and do mobility after training, you’re at a much higher risk for injury. And if you get hurt, you can’t work out.

Training breaks down your muscles and puts wear and tear on your joints. If you don’t stretch to make sure the muscle fibers heal in the correct direction, or move those joints around to keep them mobile, you’ll end up stiff, sore, and injury prone. I can’t stress enough how important this is. I’ll usually throw something on Netflix and do some mobility/stretching while watching.

6:00 pm Dinner. I usually eat at the dining hall. Occasionally if I’m tired of dining hall food, I might order something for delivery. Thanks to Covid-19, we’re not supposed to leave the OTC unless we really have to, so for the most part I stick to dining hall food since delivery can get expensive.

6:30-10:00 pm Free Time. There’s not much to do at the OTC, especially during a pandemic. I usually watch a movie or play video games. After training for 4-5 hours during the day, I need a mental break from track and field to keep myself from burning out.

10:00 pm Wind Down. I’m not someone who can just fall asleep as soon as their head hits the pillow, so I take time to relax. I usually read in bed for about an hour, then turn the light off at 11 pm. Sleep is absolutely the most important recovery tool you have as an athlete. I try to get 8-9 hours of sleep every night to make sure I’m ready for training the next day.

As you can see, life at the OTC can get pretty monotonous! As an athlete training for the Olympics, I need to focus on eating right, sleeping right, and training right, and living at the OTC eliminates a lot of distractions and really helps me do that. This lifestyle isn’t for everyone, but my goal is to represent the U.S. at the Olympics this year, and I am willing to do what it takes.

32 TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

Photos provided by Harrison Williams

TAKEOFF MAGAZINE TAKEOFF ADVERTISE HERE adele@thetakeoffmagazine.com

AUSTIN MILLER

Destination: TOKYO

Austin, when did you realize that you wanted to take a shot at making an Olympic team?

I initially had distant ambitions of trying to make an Olympic team when I first went to High Point University for track and field as a decathlete. But after I switched to just vaulting and didn’t jump quite as high in college as I would have liked, the dream started to fade. It wasn’t until the end of my senior year that the ambition was rekindled by my coach and now training partner, Scott Houston.

Who has been the most influential person in your athletic development, and why?

Scott Houston. He joined the HPU coaching staff my senior year and convinced me to keep training post collegiately. I didn’t think I was jumping high enough to seriously consider training after college, but he said with more time and further training we could accomplish some cool things. Here we are, 4 years and over a foot and a half later. We’re a pretty good match. I can be a pretty excitable human, especially when it comes to training. There are few things I love more than pushing myself to my limits in a workout and in my jumping. Unfortunately, that isn’t exactly a recipe for consistent long term success in pole vault. On the flip side, Scott is very evenkeel and levelheaded and he’s much better at seeing how all the training will come together later on in the year. So he keeps me focused on the bigger picture and keeps me from flying too far from center.

What changed in your training to take you from an average pole vaulter to an Olympic hopeful?

For me personally, I started to flourish as an athlete when I started pushing myself harder on the track and in the weight room. Speed and power are two crucial parts of pole vault. The other training adjustment was really becoming a student of the event, studying not just other vaulters’ jumps, but my own, to try

and figure out the most efficient and effective way for me to pole vault. Working with Scott, and also Earl Bell, cemented the importance of those two things in me as a vauter.

How did the postponement of the 2020 Olympics affect you?

The postponement definitely helped me. I think I could have gone to the trials and, if I had a great day, snuck a spot on the team. But the quarantine gave our group a great block of time to really dig into some high quality training and work on some weaknesses without having to worry about being fresh for competitions. I think now I can comfortably say I’m much more prepared now than I was then.

How have you handled adversity or setback in your athletic career, and what was the process like?

The only real setback I’ve experienced was a couple of freak accident injuries that happened back-to-back in the 2019 season. They kept me from getting consistent training for the first half of the year. In the grand scheme of injuries, they really were not that bad, only keeping me out for about month each. But that was the first time I was sidelined for more than a week or two, so it jarred me and made me start doubting myself for the first time. Thankfully, through the levelheadedness and uplifting support of my coaches and other vaulters and friends in the amazing pole vault community, I was able to salvage a pretty good season out of it.

That’s where having other things in life outside of vaulting becomes so important. Most likely, there will be times when vaulting isn’t going great or, God forbid, you’re injured and can’t vault. If all your self-worth, meaning, and purpose comes from your vaulting, those times can be brutal. Acceptance of the situation, patience to see it through, and finally, realizing that pole vault is just one square on this big quilt of life are three pillars that help-

34 TAKEOFF MA GAZINE

TAKEOFF MAGAZINE

Photos provided by Austin Miller

ed me tremendously with dealing with setbacks.

What is your training routine in preparation for the Olympic trials?

We lift a couple days a week, jump a few days week, and/or depending on the time of year, sprint a couple days a week, and most importantly, REST a couple days a week. Really nothing out of the ordinary. In general, we just try to consistently get a bit faster, stronger, and better at pole vault every year, regardless of the competitions, all while staying healthy. I’ll adjust as needed. If I need to focus more on vault work then I’ll make sure I’m extra fresh for vault day. If I want to get faster, I’ll get more speed work in, hit some extra running, and take a little focus off jumping big. Thankfully since Scott is good about implementing things in a planned, logical, way, he keeps my excitable self from adjusting anything way more than it needs.

How do you prepare emotionally to train and compete?

Personally, I always make sure I’m having fun. When you don’t enjoy something you’re doing, it will feel like a chore and you won’t be 100% focused and present in doing it. And when you aren’t fully present in training and competition, you’re not going to get as much out of it. Now, there are definitely times when the fun is hard to find and the heavier emotions and doubt can creep in, especially if you fall short at a big meet, or your meet results aren’t reflecting the progress you’re making in practice. It’s at those times that I truly think you have to realize that all those ups and down come as a package deal, as part of the total journey. The ups- the successes and triumphs- those are always fun. But the downsthe set backs- those can be tough, daunting, uncertain times. At the end of the day though, the whole journey is an incredible experience that I’m so lucky to be a part of, and that appreciation and gratitude of being able to chase this dream period is something that keeps me emotionally level.

What have you sacrificed to chase the Olympic dream?

I guess to the outside observer, one could say my social life, some financial security, and professional ventures outside of pole vault have taken a back seat, but to be completely honest, I don’t think I’ve had to sacrifice much. I’m lucky enough to live this chapter of my life devoted to bettering myself physically and mentally and trying to solve this crazy pole vault puzzle. I love it! I may not be going out each weekend with friends, but I am competing most weekends with my friends. I may not work a stable 9-5 every week, but I get to explore the potential of my body and my vault every week at practice with friends, and share my love of this sport with others through coaching. I may not travel the globe for vacations, but I have gotten to go across the globe to compete with friends. It’s not a stifled life at all, just a different one.

What do you do to support yourself financially?

I work security for a local music venue in Greensboro called, The Blind Tiger. I also coach pole vault at the Vault House pole vault club in High Point, NC and at Ragsdale High School in Jamestown, NC. I coach club lacrosse at High Point University. Additionally, I write for a music publication called, This Song Is Sick. I’m involved with a fair number of things, but I love all of it, so none of it really seems like a chore. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention my family also. I’m extremely lucky, blessed, and thankful to have a family that is supportive of my pursuit of this dream. There have been a few occasions where they’ve helped me get plane tickets to big meets.

If you knew then what you know now, what would you have changed about your athletic career?

I would have started weight lifting in high school; found a vault club in high school; and become a student of the event way sooner. I didn’t know ANYTHING about pole vaulters past or present until I was almost done with college. You can learn so much from watching other vaulters and experimenting with new ideas on the runway.

With limited meets taking place as a result

36 TAKEOFF MA GAZINE

of Covid-19, how are you approaching the year?

i am lucky to have a phenomenal facility in Vault House so we’re hosting more club meets for any vaulters interested. The field size is obviously small due to Covid restrictions, but competition experience is competition experience. It’s ironic, even though there are fewer meets in general, we’re competing more this year now that we’ve started hosting competitions at the club.

How do you think becoming an Olympian would change your life?

It will potentially open a whole new world for me. It will definitely open the door to more high level, overseas competitions, and personally it would be a peak highlight of my pole vault journey to represent the U.S. that has such a rich history in track & field. To be completely honest though, making an Olympic team is just one happy by-product of this opportunity. At the end of the day, I’m just trying to jump as high as I possibly can, and if an Olympic team comes as a result-amazing. If not, I’m still going to try and jump as high as possible and savor every second of this incredible chapter of my life.

What are your interests and professional goals outside of pole vaulting?