BFA . ILLUSTRATION 2O23

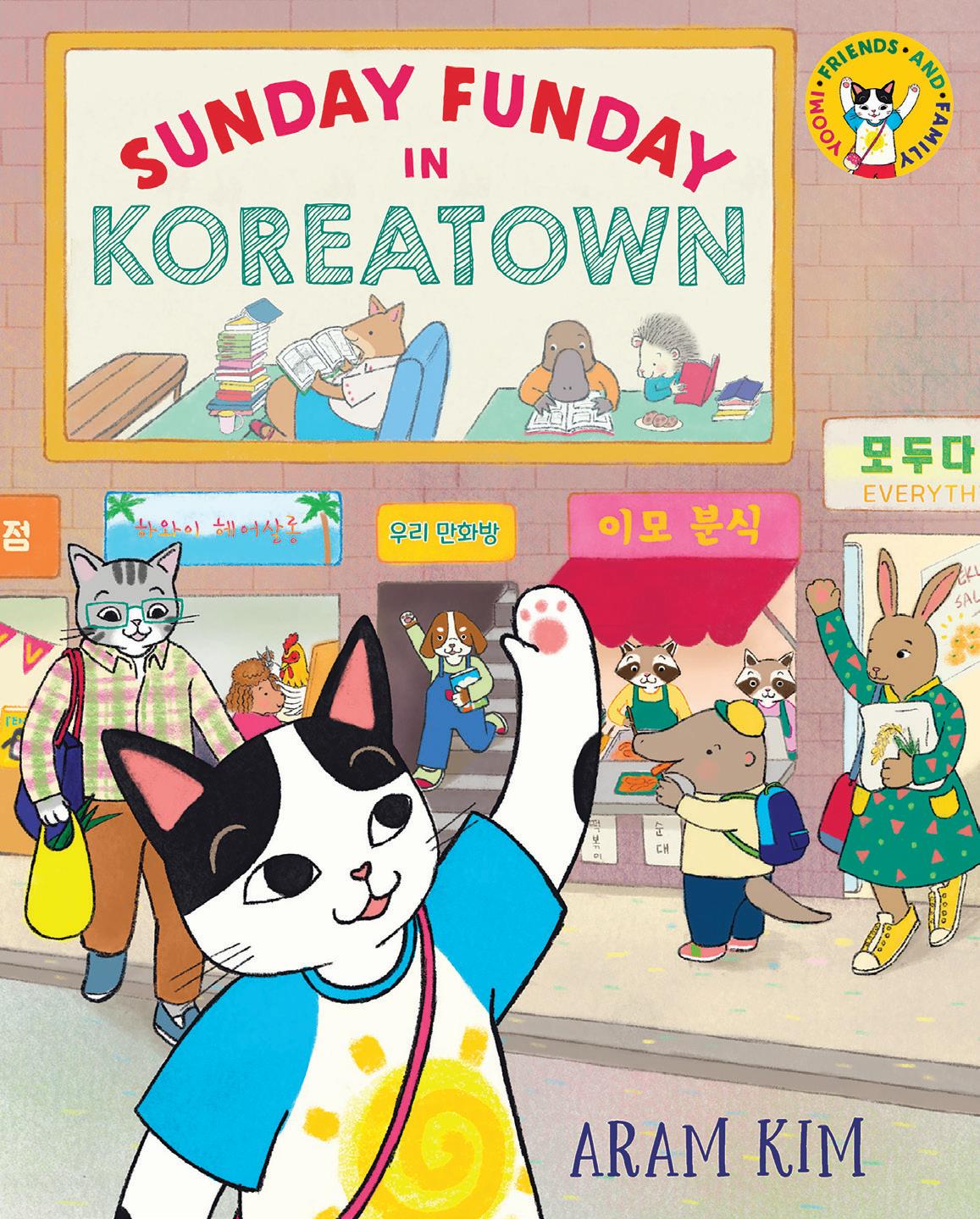

Stephen Savage in conversation with Aram Kim

+ The Art of Illustration by Charles Hively

• BFA ILLUSTRATION • 2O23

When dust from a long academic year somehow settles, it’s time to reflect, debrief and tackle this publication. Meetings, lists of names and suggestions, curating and paginating the work, evaluating what was produced beyond our senior thesis project. Also impressive breakthroughs—or any lack thereof—are carefully discussed as this book gradually comes together. Additionally, an important writing component takes shape through which esteemed faculty and alumni interview each other along with commissioning thought provoking industry essays.

While this compendium showcases notable results, these only represent a fraction of graduate achievements and processes progressing in sketchbooks and tablets even as we speak. Now that our seniors venture beyond any familiar support academic environments provide, instincts, intuition, and training in craft and concept are kicking in to help them navigate these open waters.

When dreams come face to face with industry in its more or less defined, established or developing platforms, they have to find or carve their own way to audiences who respond. Striving for personal voice or conforming, expressing or impressing, digitally or traditionally, through work that matters or delights, these are only some of the choices illustrators have to make in order to establish a personal balance between art and commerce.

The nature, proportions and intensity of these variables change in every assignment, asking artists to decide if they should work from the inside out or from the outside in. Real marketplace dilemmas and their rewards will soon replace students’ fear and excitement while venturing to chart and define their own pictorial territories. After all, we intentionally provide them with compasses, not maps.

This introductory note would be incomplete without recognizing the many talents going into a publication like this—from our gifted students to our long list of outstanding faculty and our department team. Thank you to SVA President David Rhodes for his trust, meaningful guidance and ongoing support. I am deeply grateful to the tireless Carolyn Hinkson-Jenkins, Matthew Bustamonte, Jason Little, Kelsey Short, Heaven Boles and their passion for this project, their ideas and care in introducing our brilliant 2023 graduating class to industries they are about to deeply transform.

As challenging as it is to crystallize the spirit of this department and provide a tangible memento of the work, thinking and spark that make BFA Illustration tick, this publication will come very close.

See you at school, Viktor Koen Chair

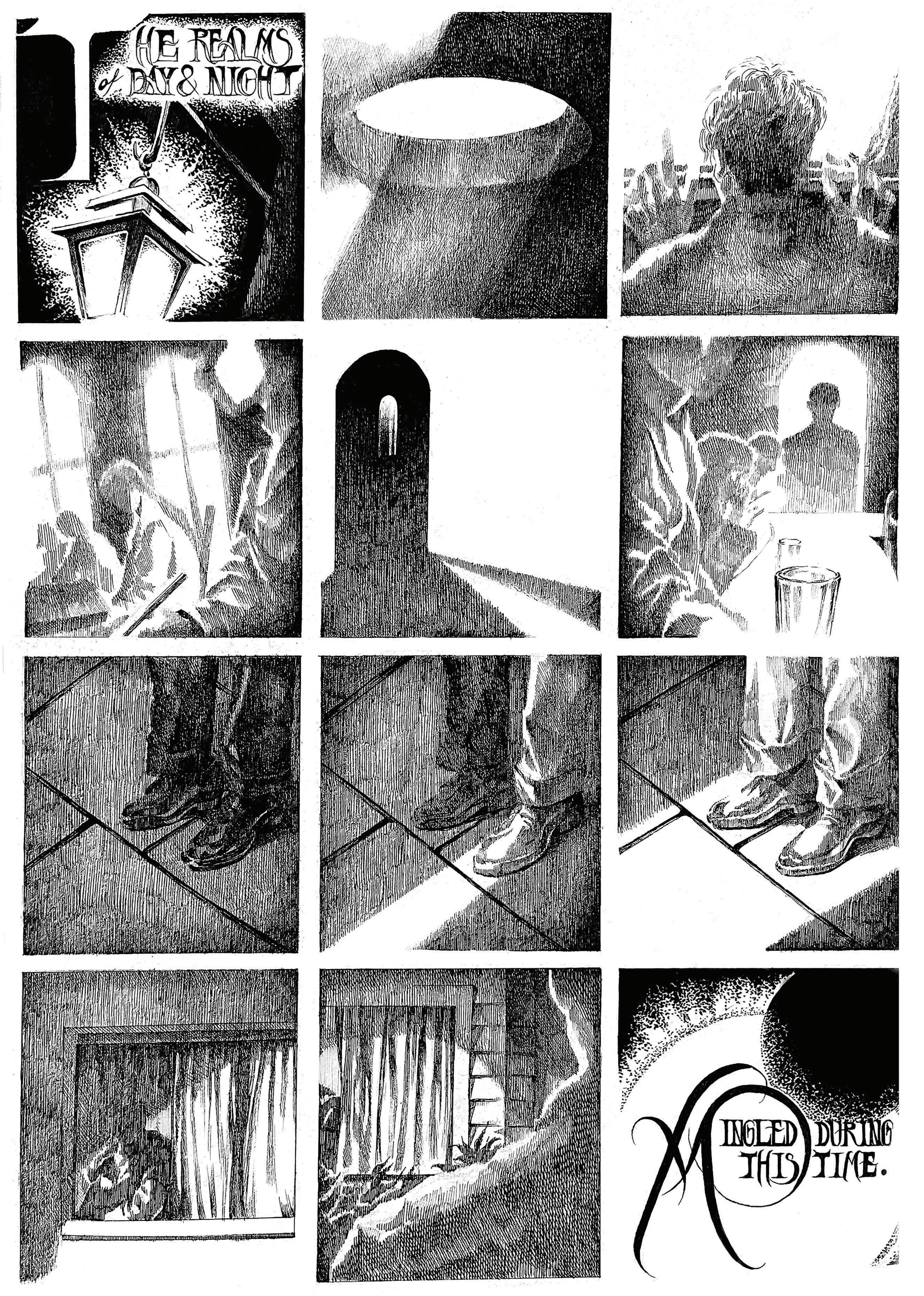

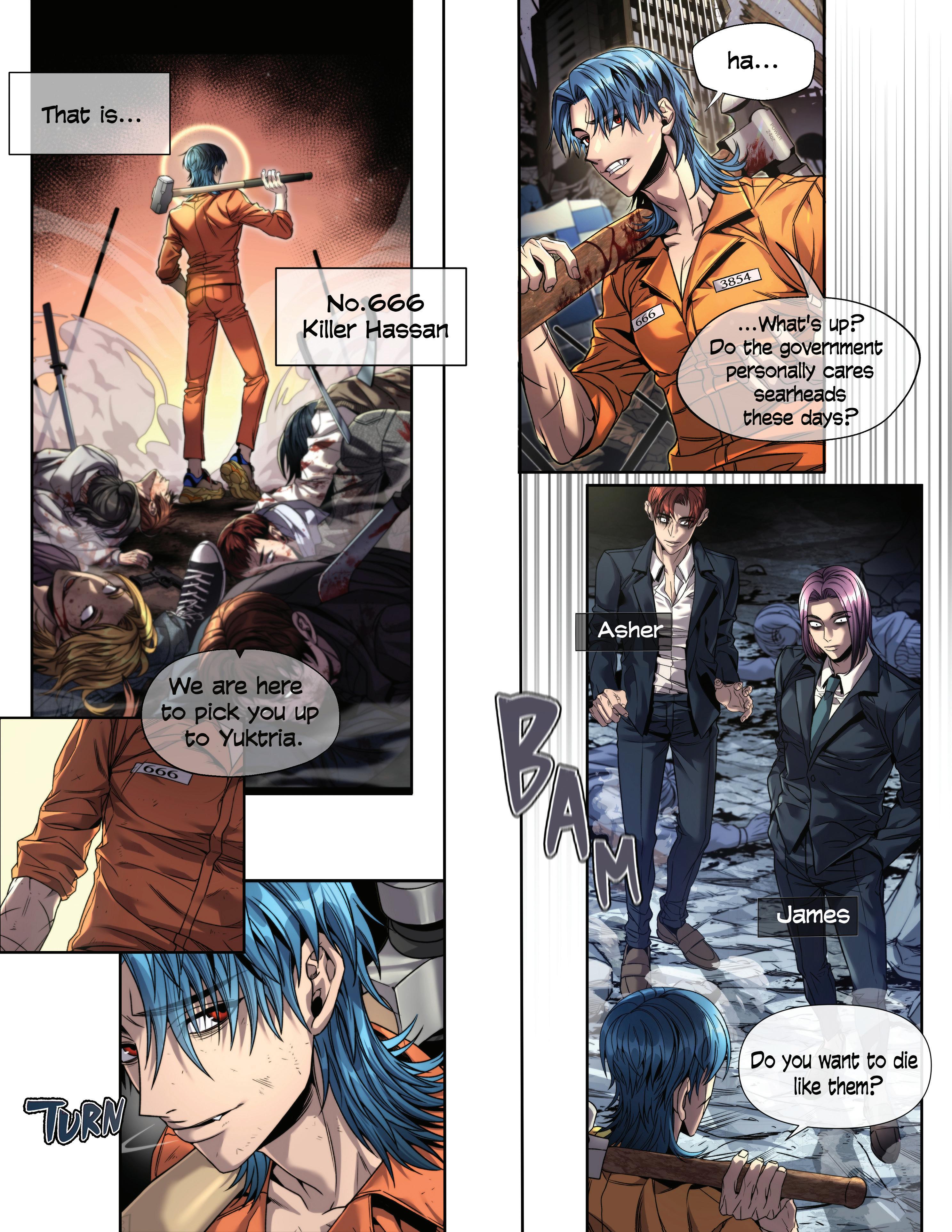

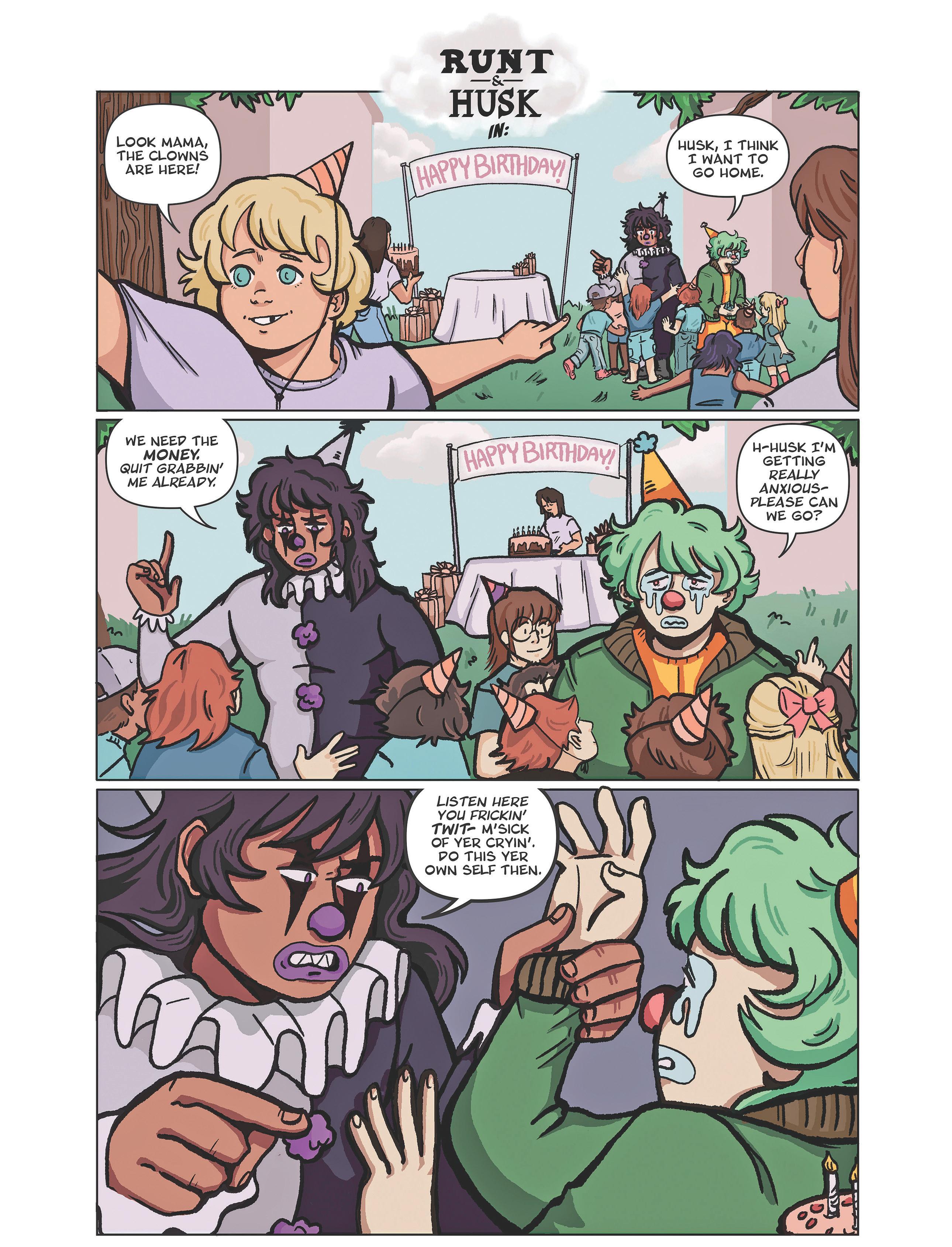

BFA Comics

BFA Illustration

STEVE BRODNER

JOSH COCHRAN

JENSINE ECKWALL

LISK FENG

FRANCES JETTER

VIKTOR KOEN

ANTHONY MACBAIN

MARVIN MATTELSON

LILY PADULA

MATT ROTA

CECILIA RUIZ LOPEZ

DOUG SALATI

YUKO SHIMIZU

VESPER STAMPER

SARAH VACCARIELLO

SAM WEBER

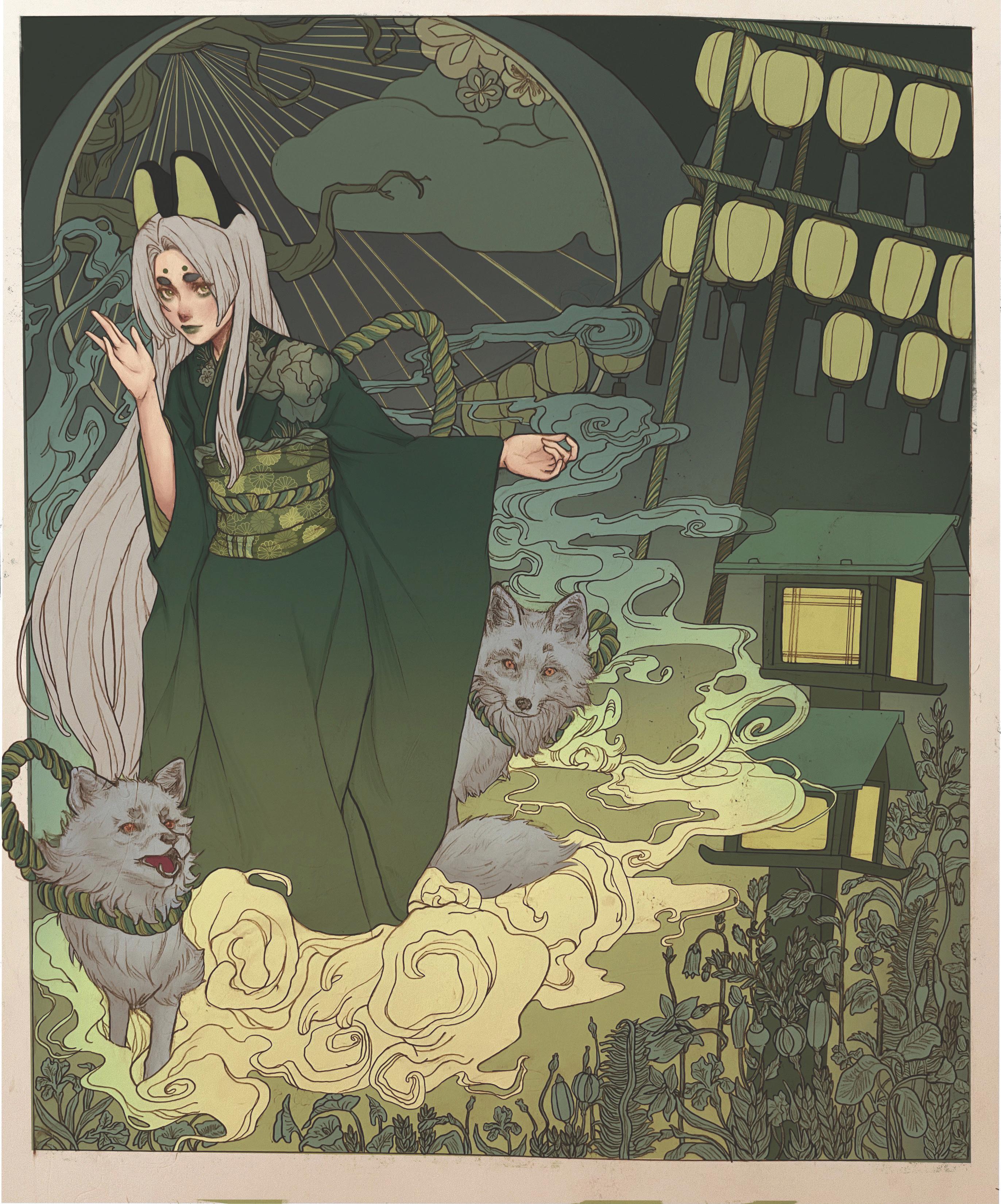

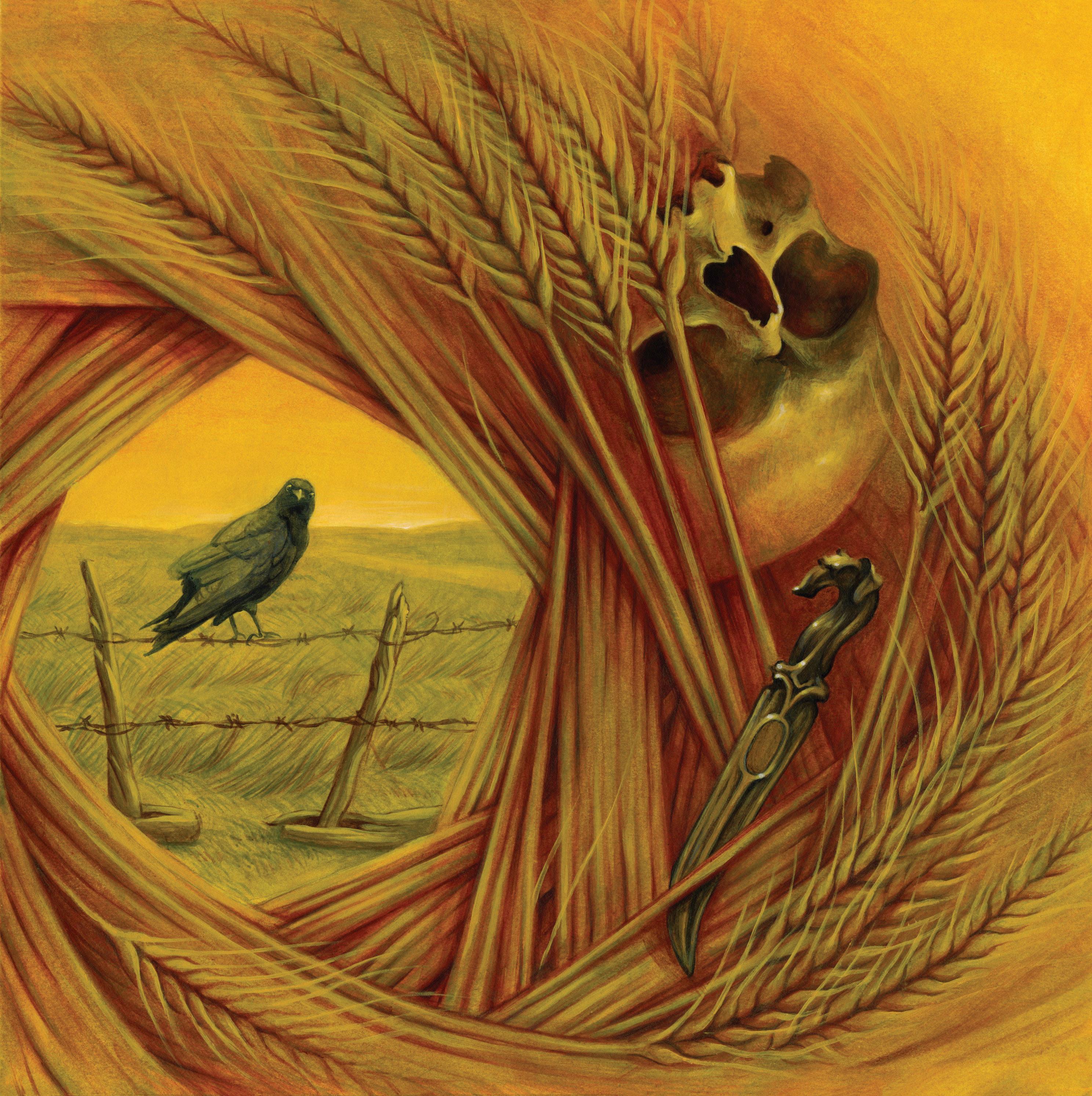

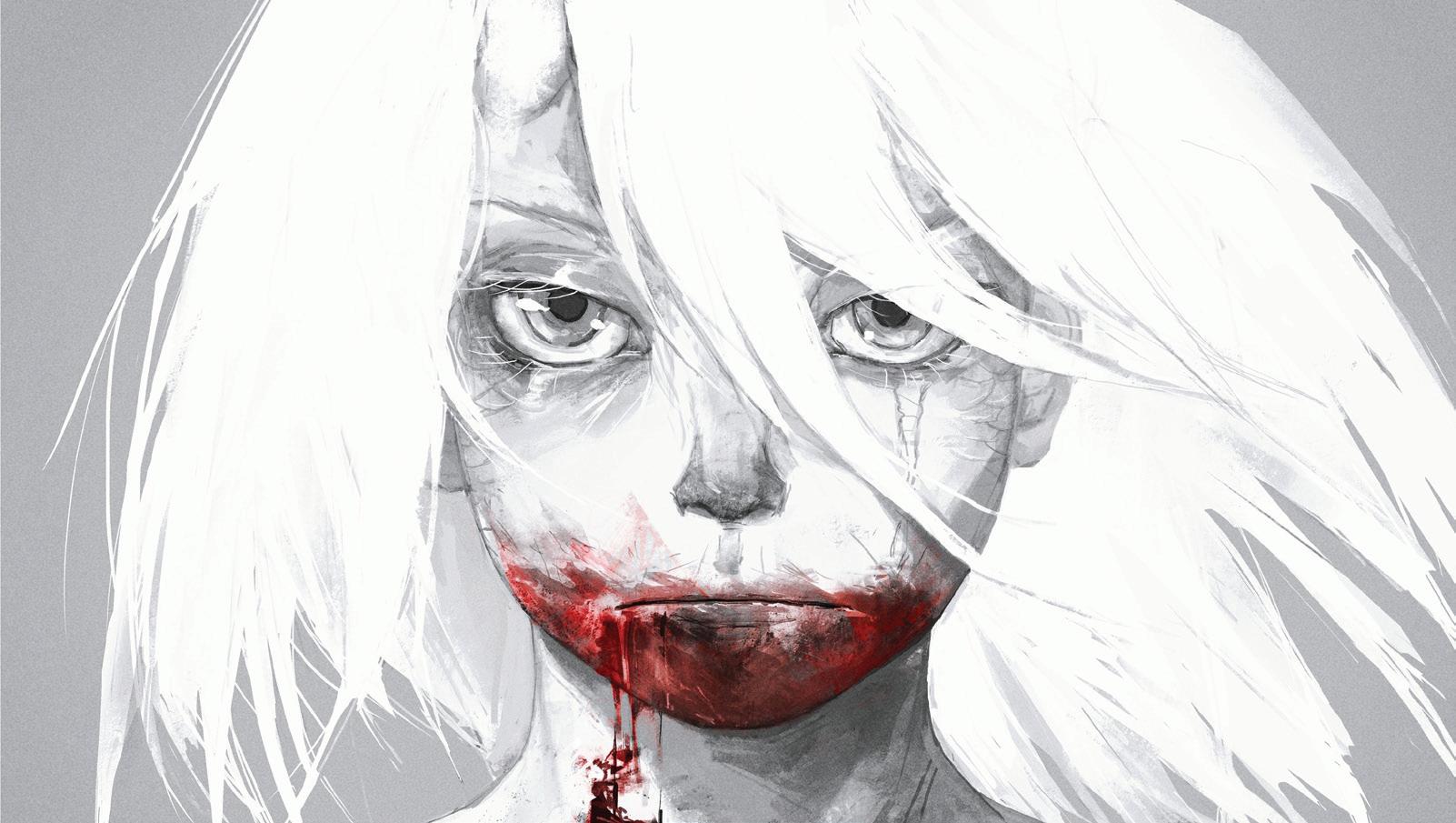

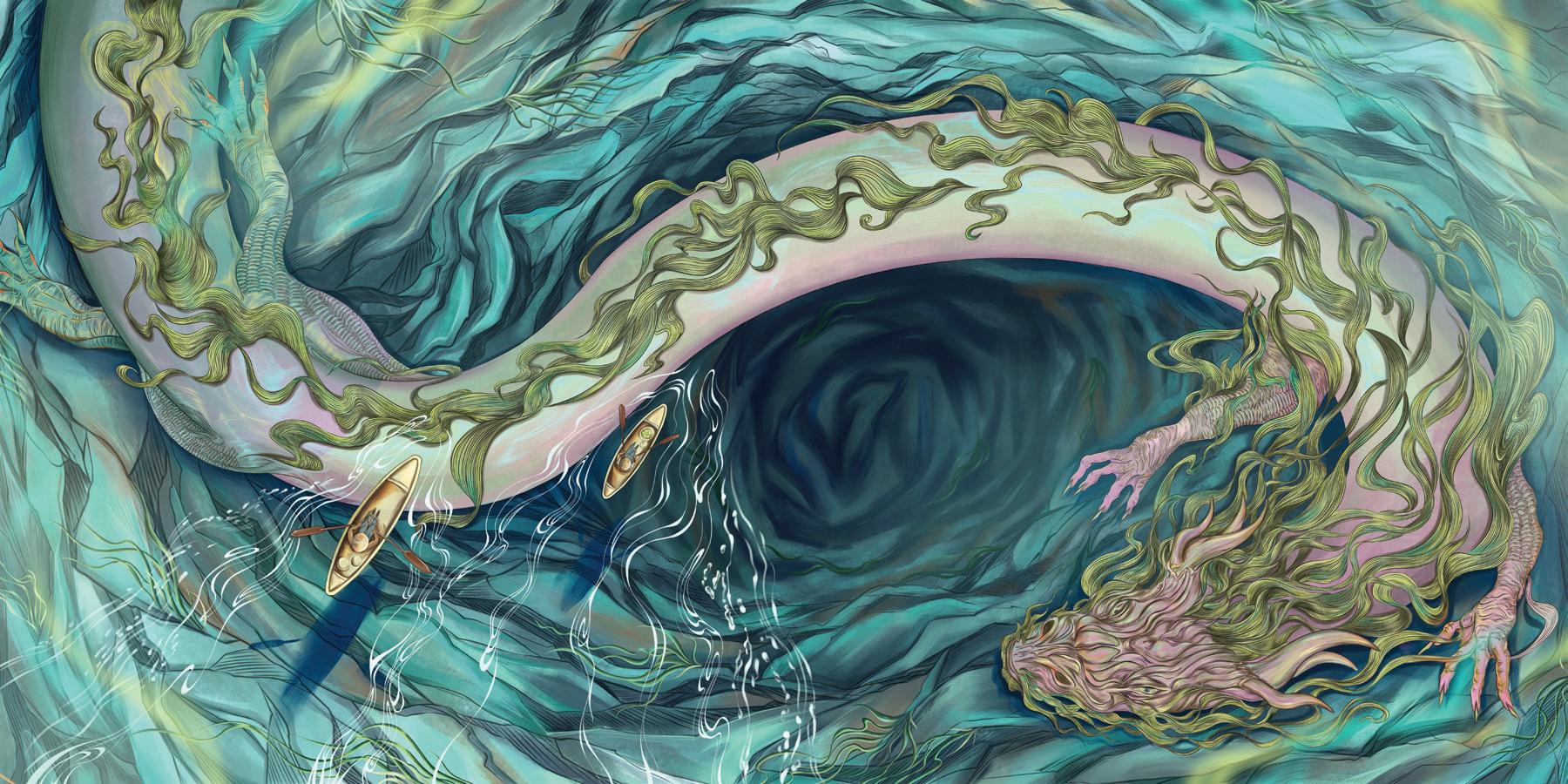

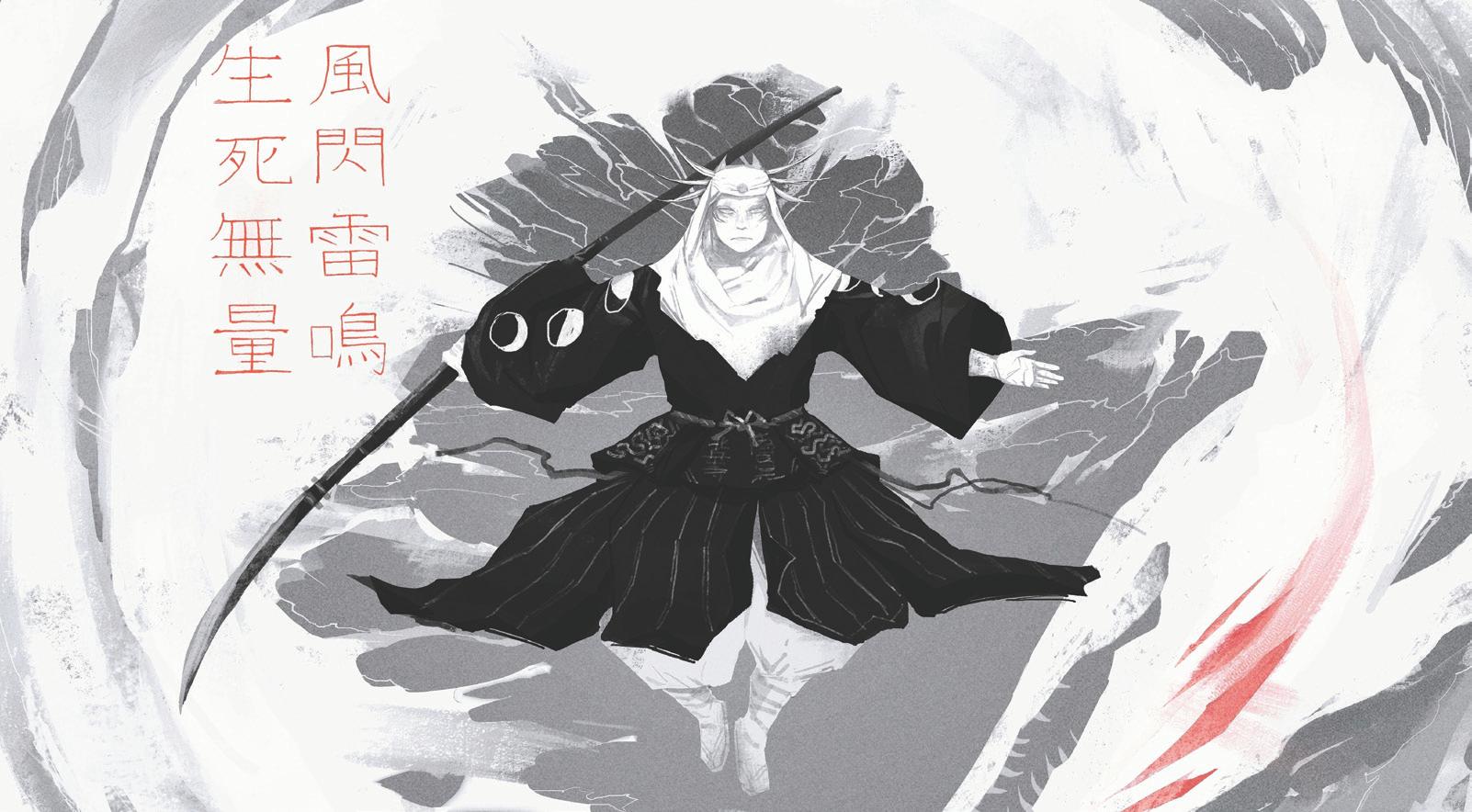

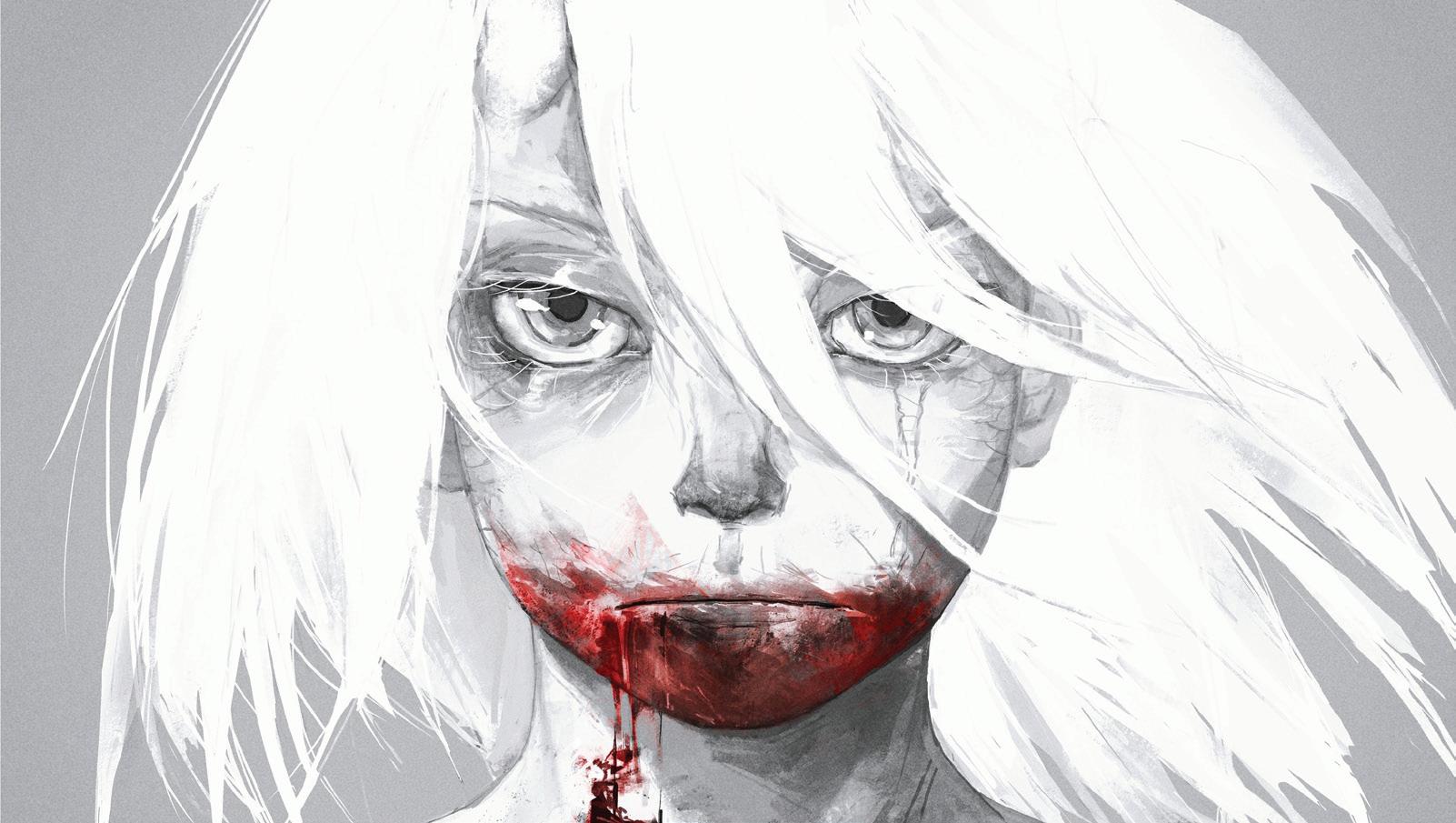

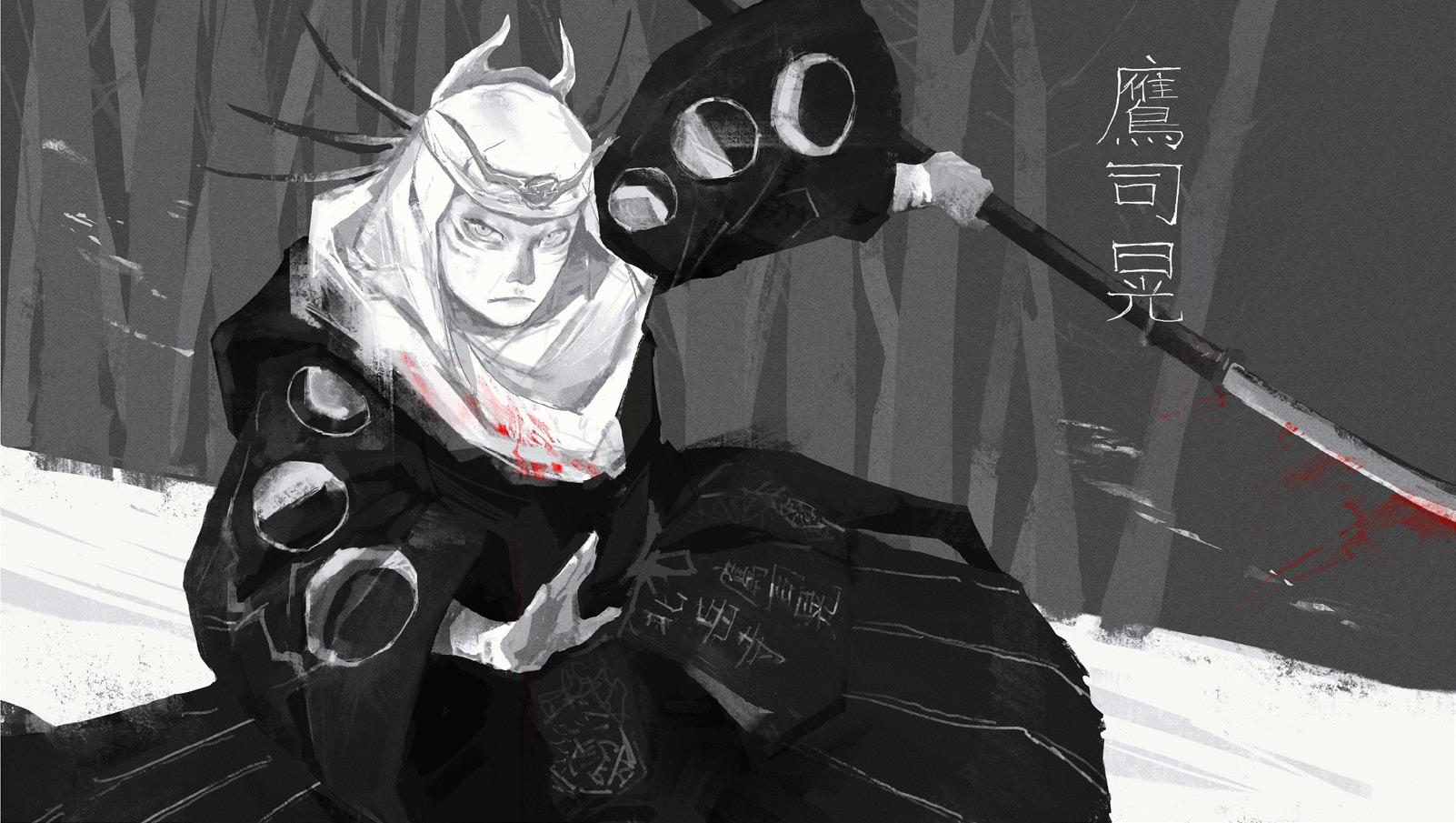

Cover: Xinyi Pan

Yunyao Chen 20 Jiaxi Chen 21 Letao Sun 22 Yi Chen 23 Xi Jin 24 Mifei Zhou 25 Yawen Hu 26 Xin Huang 27 Rongzhang Ye 28 Songer Yang 29 Yutong Du 30 Yinghao Lin 31 Haochen Wang 32 Jenna Park 33 Wenbo Wu 34 Sirui Zou 35 Oliver Perry 36 Maria Bautista Signorini 37 Ruoshui Liu 38 Yujing Huang 39 Xiaozhu Cui 40 Samantha Wang 41 Qingru Yang 42 Mutong Liu 43 Yuxin Ding 44 Yiyang Liu 45 Xinyun Chen 46 Yuhe Zhuang 47 Xiaohan Guo 48 Xiaoyu Zhang 49 Yiwei Wang 50 Lutong He 51 Jihae Park 52 Zachary Guzman 53 Long Lin 54 Huaixuan Xiang 55 Damian Gary 56 Emo Kiddo 57 Emani Simons 58 Ella Shi 59 Ning Jiang 60 Louie Martin 61 Ria Varma 62 Timo Chou 63 Yubin Lee 64 Ji Ling Wu Li 65 Hope Xi 66 Justin Jung 67 Yiyang Yvonne Li 68 Le Cong Nguyen Nguyen 69 Jasmine Chan 70 Hanyu Yang 71 Yueyi Zhang 72 Yijiang Dong 73 Laís Rojas 74 Jingyi Cai 75 Zhihan Zhang 76 Mckenzie Jones 77 Alana Green 78 Wenjun Shao 79 Huilin Gui 80 Lauren Giancola 81 Carolina Gajardo 82 Vivian Liang 83 Verum Zhou 84 Ariel Miner 86 Denise Alayón 88 Jehao Wu 90 Mansi Vinay 92 Maxine Zhou 94 Jingyao He 96 Sunny Ruan 98 Jim Liang 100 Yiwen You 102 Yilin Zhu 104 BFA Illustration

Thesis Faculty

SENIORS

Senior

PANSHANDY.COM @PANSHANDY

A CONVERSATION WITH

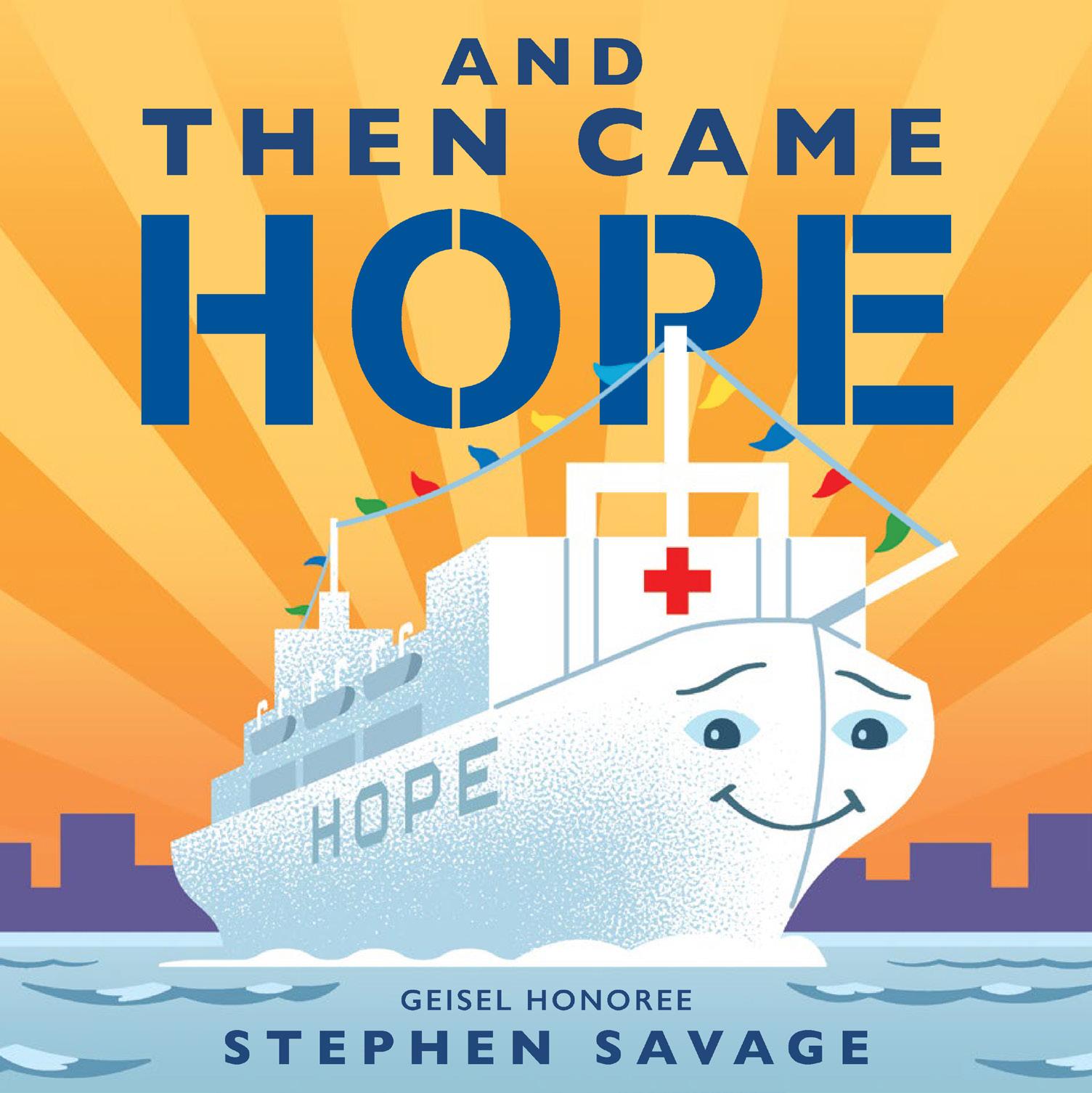

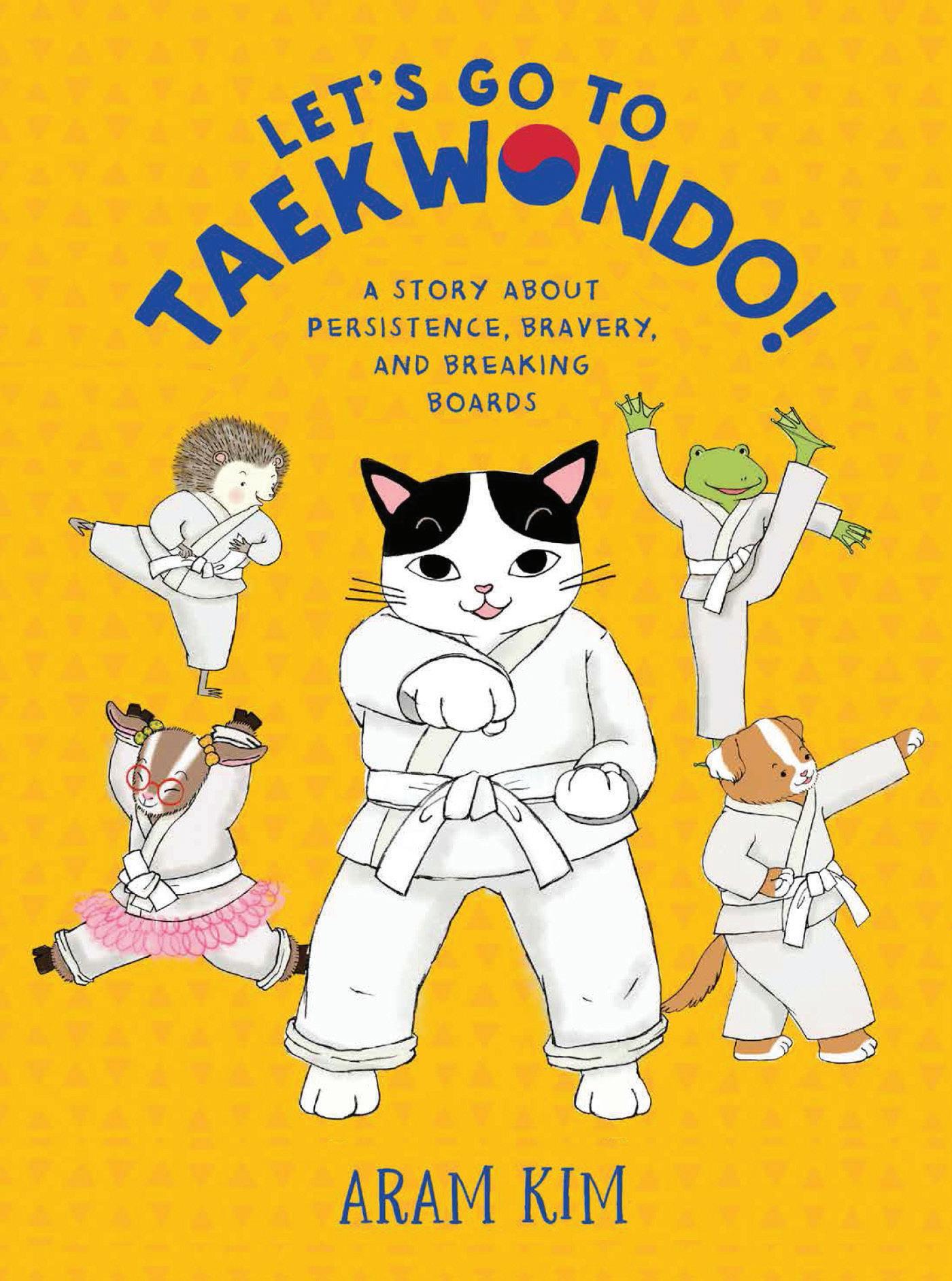

Stephen Savage & Aram Kim

STEPHEN: So Aram, I always knew that you were a fabulous children’s book illustrator. I especially love the sweet and gentle Cat on the Bus. And then Emily Feinberg, your colleague and my editor at Roaring Brook Press, we’re working on a book with her called Rescue Cat. Emily told me Aram Kim is going to be my art director. And I said wait, “Aram Kim? She’s an illustrator!” I was totally confused and I didn’t realize that you wore both of these hats.

So, I know that you’ve illustrated five books. How did you stumble upon children’s books as the path that you wanted to get on?

ARAM: I think there is always this misunderstanding about children’s books that they are just cute drawings, but if you pick up any children’s book now from the bookstore and read it, they are very deep; the storytelling is really solid; and all the settings that the illustrators create are well thought out. So it’s not the cute, easy path at all.

STEPHEN: It’s not like adult stories watereddown or lightened up. They are just as deep and just as intense and have just as much substance as any other kind of story.

ARAM: That first year I came to New York, I was walking around the city just exploring, and I happened to go into Barnes and Noble. I was walking around, looking at the books, but when I got to the children’s book section, I just couldn’t walk away. I so vividly remember picking up Maurice Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen and I was shocked by how good it was. I didn’t grow up with Maurice Sendak. I didn’t even know he was alive at that time, but I was looking at this book and I remember thinking that the story was so good. And the Illustrations are amazing. It’s so well designed as a whole package.

It’s very accessible and the story wasn’t just for kids, it was very enjoyable for anyone.

“Draw what you like, draw what you know”

–Marshall Arisman

I still have that copy, but I didn’t think that I was going to be a children’s book creator, or that it was even a career. I did take one children’s book class when I was a junior with Yumi Ha. During that class, I learned how to make a dummy book for the first time, and she taught us about how to submit to publishers. I continued working on children’s book art in my thesis year and after I graduated. After graduation, I did research and I dropped off my portfolio with publishers. But there was nothing solid coming out of it because my work wasn’t very strong.

STEPHEN: That always happens. You have to start at the bottom. You have to start with nothing to show or nothing of quality, and people have to say you’re not there yet—you don’t have anything yet.

ARAM: You know that’s so hard to hear. And I don’t mean hard to hear emotionally, but no professional would say that because no one is that invested in you, to tell you the truth. No one wants to be a bad person and say, “Hey, your portfolio is not good enough. You have to improve yourself.” Something which is so important, but it’s really hard to find anyone who would tell you that.

STEPHEN: It wasn’t until 10 years after graduation that I started doing kids’ books.

I had some success with the editorial work, and I wanted to try something different. I had a friend who was starting to publish at Scholastic with David

Saylor, and I sent him a promotional postcard. It was a portrait of Cary Grant. If you sent a picture or a portrait of Cary Grant to someone in children’s books today, they’d think it should have gone to an editorial art director.

But [David Saylor] could see the essence of my style in that portrait and thought that it could work for a children’s book. So there was a lot of room for latitude in these decisions. There’s not as much these days; now you have to hit the ground running.

[David Sayor] knew that I had another career in illustration, that I wasn’t a beginner. I think there was a trend also at the time when editors were plucking illustrators from the pages of magazines and newspapers.

It’s interesting when I think back to those days because, as I said, I don’t think I was ready. I had these naive perceptions of what a children’s book writer is. For my first book, Polar Bear Night, I was able to learn on the job.

ARAM: If people are willing to learn and can work collaboratively, they always end up making great work.

STEPHEN: Your thesis was a book that actually got published, Cat on the Bus Did that book need a lot of help or were you able to take your thesis and just turn it over to the publisher? Did it need a lot of work, a lot of editing?

ARAM: A lot of editing was done during the program with the help of Pat Cummings, who was my advisor at the time. She was just an excellent mentor. Everything I’ve done in children’s books I owe to her. I learned so much over time. And I did three pieces at a time with her. That was her advice—doing multiple projects at the same time, and Cat on the Bus was one of them. After graduating, I really pushed that book to be submitted because it was the book that was getting the most reaction from people.

I’d go to a few publishers, and then

each time I got feedback, I would make edits, but the big arc in the story actually stayed pretty much intact. The biggest change they made during the submission process was adding text because it was originally a wordless book. Wordless books are amazing for creators who want to tell stories through pictures, but it’s very hard to sell on the market.

I got great feedback from an editor from FSG [Farrar, Straus and Giroux] to bring in some text, and then it actually got published by Holiday House.

STEPHEN: So [Pat Cummings] makes you work on a bunch of projects so that you don’t put all your eggs in one basket, that you’re trying different things.

after I graduated from the MFA program. It was an amazing experience. I got to see all the original art from Sophie Blackall and Jerry Pinkney, these great illustrators who were already working with Little Brown. It was a great experience to see how these things work, like what is done when illustrators submit, how they review work, how they have to talk to all these different departments in the publishing house, like the editorial department, design department, production department, copy editing department; it’s all such a collaborative process that I didn’t know about. I never would have thought that I was suited for a corporate environment, but I was really enjoying it, so I ended up staying as a freelancer. During that time, Cat on the Bus was published and the design team came to celebrate with me. By that time, I was working on my second book, so I thought I had learned all the secrets. I thought I should be ready to go off as a full time author and illustrator. So I left Little Brown to work on my book, and then worked continuously as a freelance book designer with different publishers. One year later, I started working as a full time designer again at MacMillan.

provide a vision. The illustrators are in a state of chaos and flux and the art director is kind of like the adult in the room who tells them to wait, calm down, you’ll be fine. So without that kind of guidance, the book doesn’t get made. There has to be a captain of the ship, that’s what the art director is.

ARAM: I really love the process that we have working together. Another thing that I want creators to know is that there is a whole team working on your book. There’s a production manager, who chooses the paper; a special effects and production editor who’s working on the grammar and punctuations and spacing between the text; so many people rooting for your book.

ARAM: When you work on one project, especially as a student, you get so attached to it that you don’t let things go. It’s hard to get feedback, and then you’re stuck with one idea or story. And so I think it actually gives you room to have some distance from your personal project and be more objective.

STEPHEN: So you’re my art director right now, and we’re linked in all these different ways. Did you start art directing right away after graduation?

ARAM: It’s been only about three years since I started working as an art director. I started as an intern at Little Brown Books, but that happened the summer

STEPHEN: When I found out that you were my art director, I already knew your books, and I saw that you art-directed We Are Water Protectors, which won a Caldecott in 2021. And there’s another, A Place Inside of Me? That also got a Caldecott honor—

ARAM: It was the same year, which was insane to me. You never know which book will win the Caldecott awards. I do the same work for every single title. When it comes to winning awards, for me, it’s luck. But for the illustrators, it’s pure work, right?

STEPHEN: I disagree. The art director’s vision of the book is key. Of course, the illustrator is making the images, but an illustrator relies on the art director to

STEPHEN: When doing both illustration and art direction, do they help each other? Most of the art directors that I work with are not artists. So when I have an art director like you, it feels different when you give me feedback because it’s coming from another illustrator. You can be really sensitive to my needs as an illustrator, whereas most of the time, an art director is a designer and doesn’t know that much about illustration. I’m not saying that’s bad, but they don’t know anything about the picture-making process and might not be able to help me solve a problem. But I’m curious, you work at Macmillan and then you come home to work on your own books. How do the two things feed each other?

ARAM: Normally I think they work well together, except for one thing, which is that I’m so tired! Aside from a time crunch, I think the synergy between getting to work with other illustrators as an art director is great because I get so much inspiration by seeing different illustrators’ work and processes. And because I work with so many different people, I see so many different ways of solving problems. Also, being on the side that reviews their art and gives feedback has given me the ability to look at my

own work objectively. I couldn’t do that before working as an art director—you get too attached. When I give feedback to myself, it’s as if I’m critiquing an illustrator that I’m working with.

STEPHEN: That’s amazing. That’s a skill that illustrators really need to develop.

ARAM: It’s hard!

STEPHEN: You need good illustrators who can be art directors for their own work— to know what needs to be better, what part isn’t working.

ARAM: Yeah, that’s such great practice for students. The illustrators I work with

give me a little more credit because I’m an illustrator, so it feels more collaborative. There is kind of a mutual respect. I am blown away when I get artwork from illustrators, and that feeling never goes away.

STEPHEN: I just got my corrections yesterday for Rescue Cat from Astor, a designer who works for you. The email was several pages long! It’s funny because during the initial read of all the notes, all I could think was I can’t do that! I can’t change that! But then I realized these are all things that are going to make the book better. You know a children’s book takes a long time, so it’s a long slog. I’ve been working on that artwork for six months,

and now I have all these things to do, all these changes to make. You’re running a marathon and someone pushes back the finish line. It’s so amazing to have people that are looking at the work and are invested in the book. There was a lot of thoughtfulness that went into those notes that you guys sent over.

ARAM: Art directors really do care. And we love Rescue Cat! Emily, the editor, is so in love with the book.

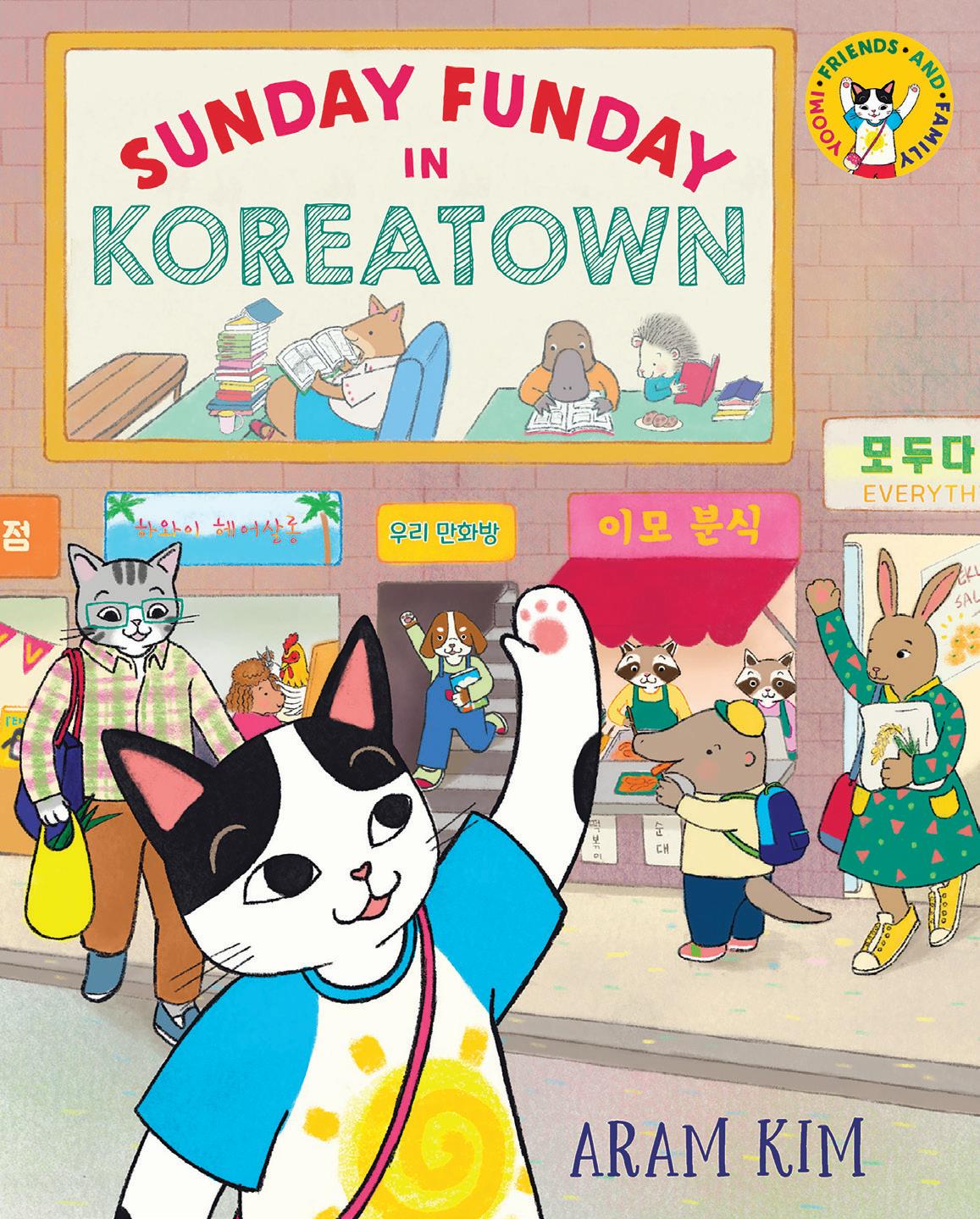

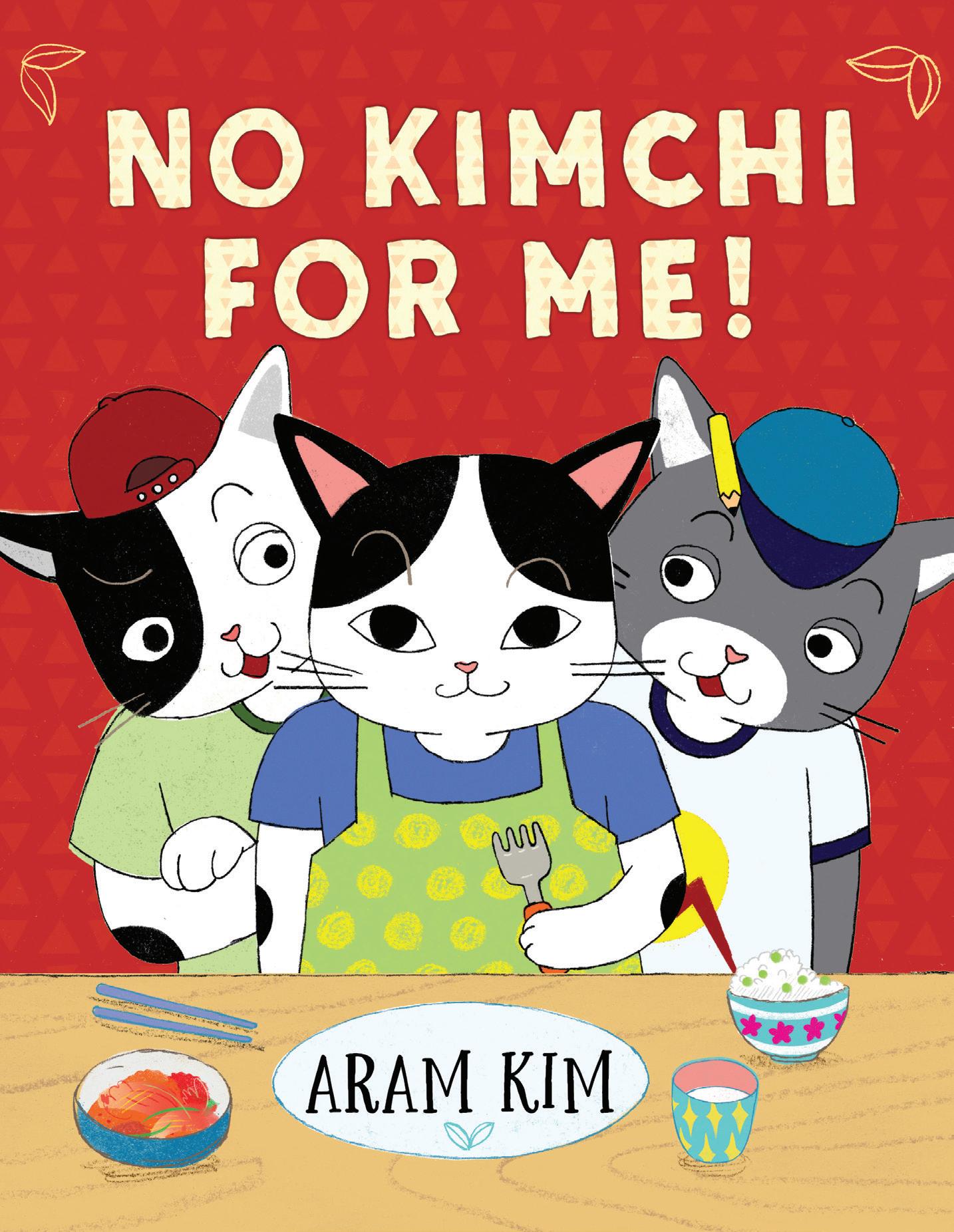

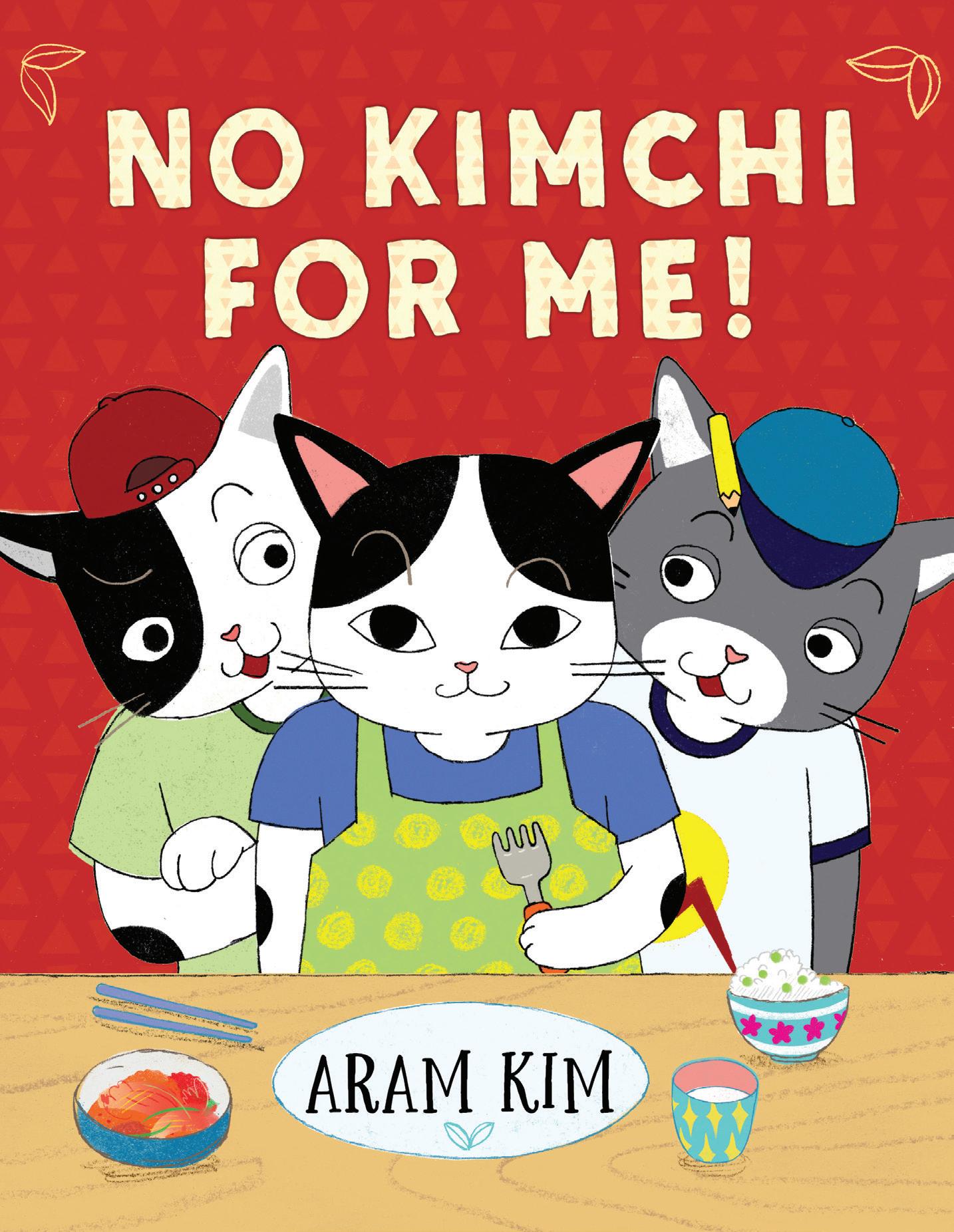

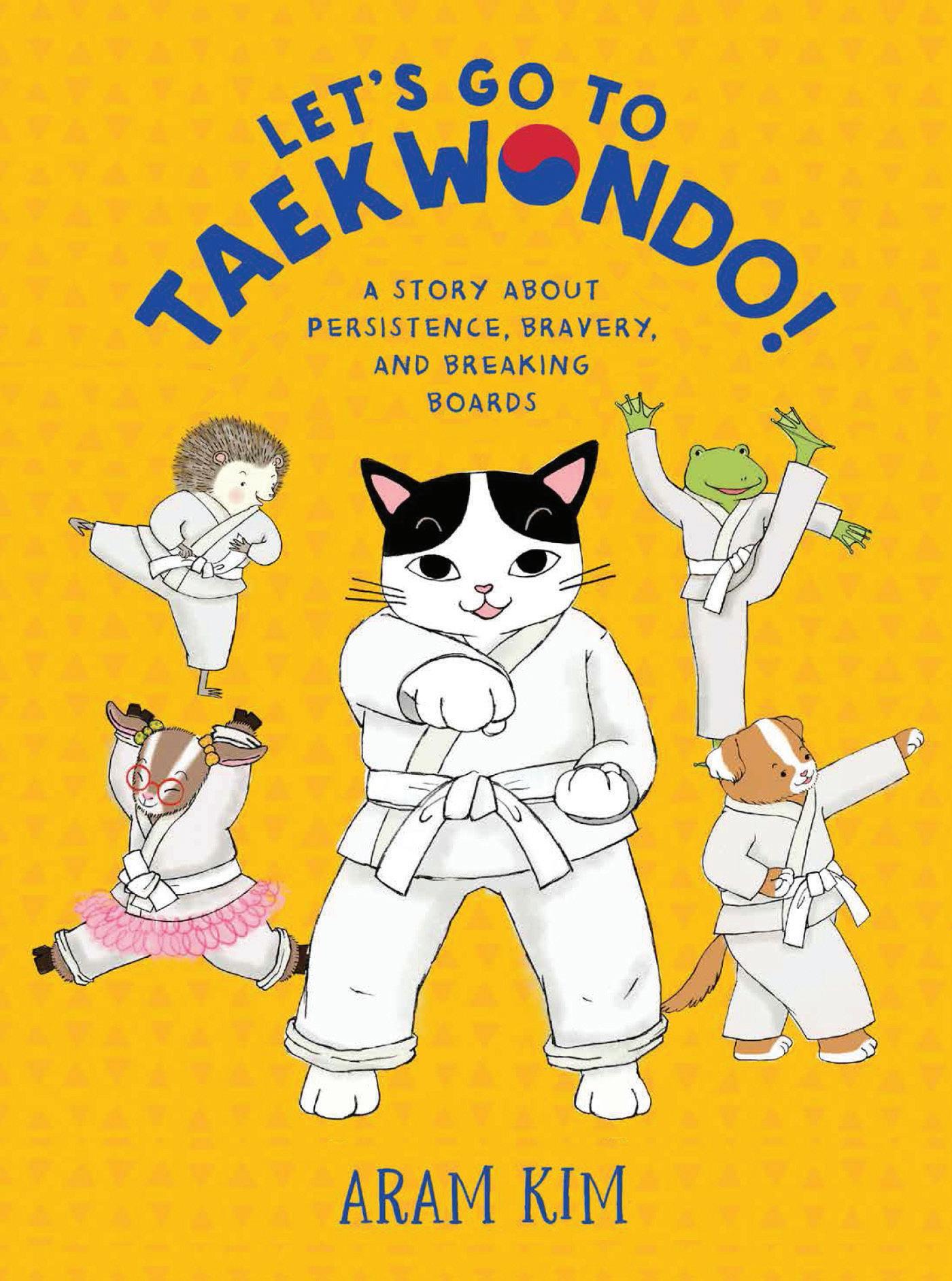

STEPHEN: I’m so excited to hear that there’s that much love for the book. I also think it’s hysterical that four of your five books have had cats in them, and now I’m doing a cat book.

ARAM: Draw what you like and draw what you know, right?

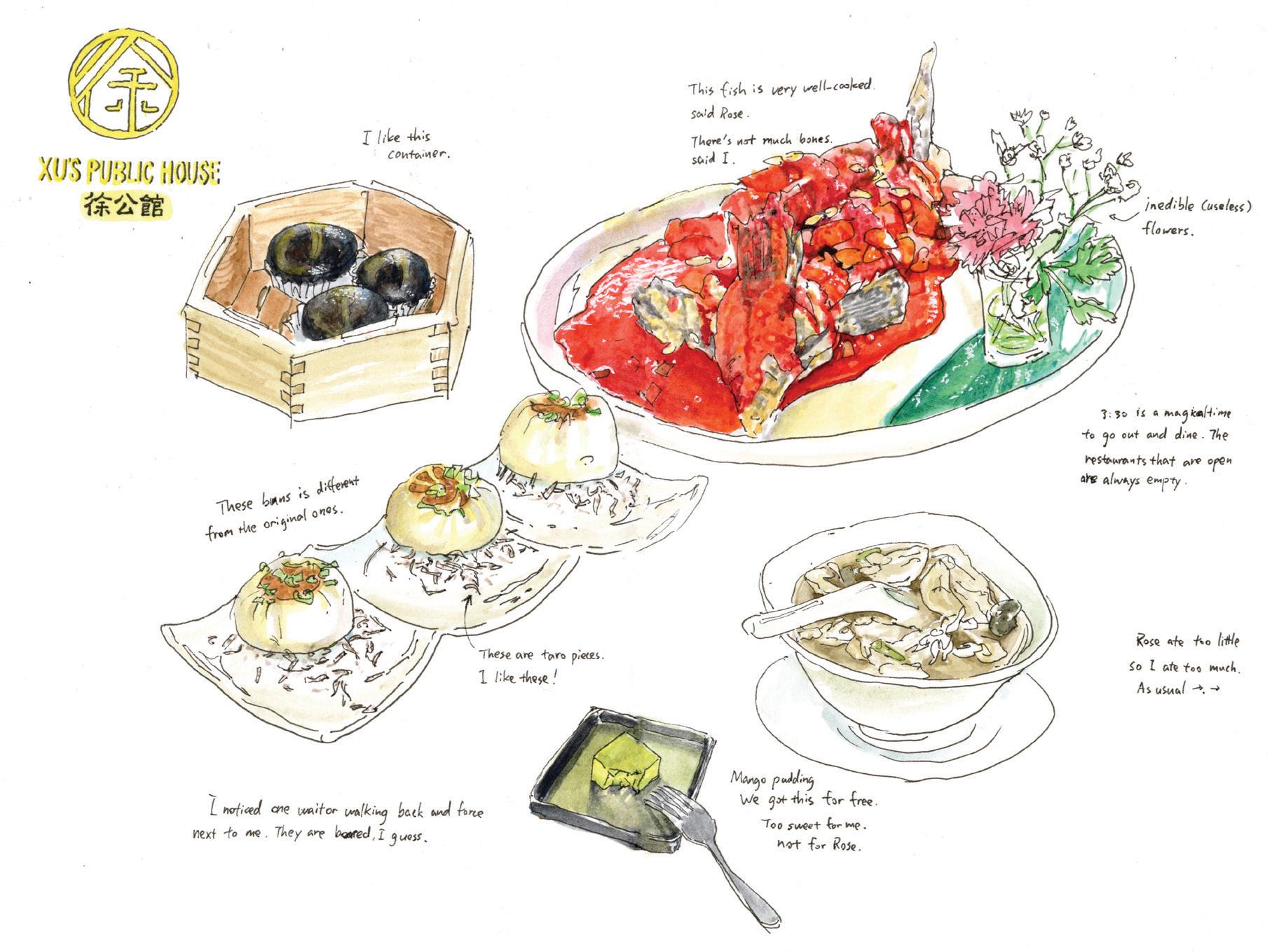

STEPHEN: It takes a lot of courage when you’re young to say, “Oh, draw what you like” and “Well, I don’t know what I like!” I started thinking about becoming an illustrator in 2006—that’s 15 years ago. But you’ve been on this journey for a long time to try to answer those two very simple questions. You showcase your Korean heritage so beautifully in your books. How long did it take for you to figure out that that’s what you wanted to do?

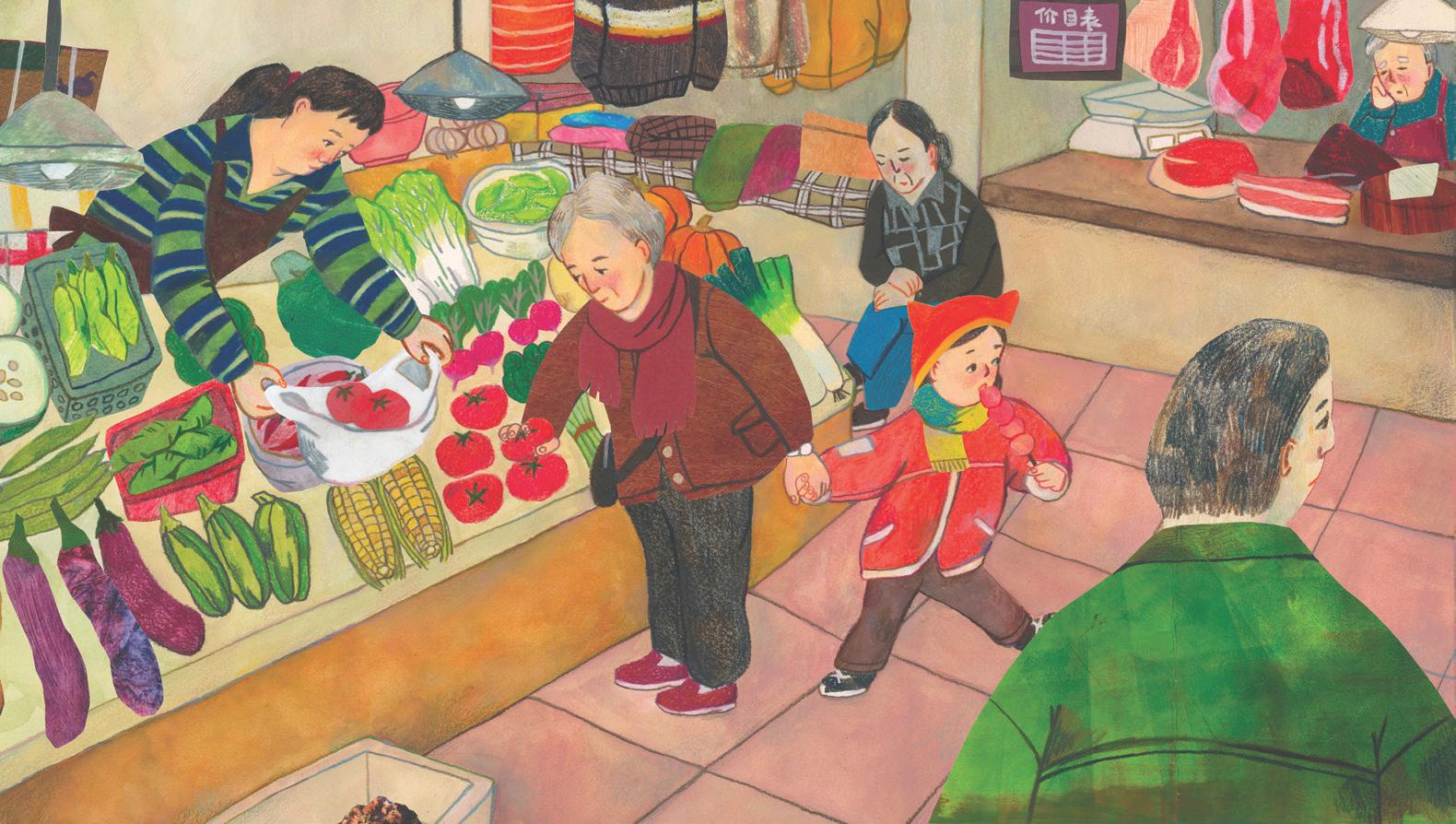

ARAM: When I was in the MFA program, Marshall Arisman said, “Draw what you like, draw what you know.” I remember writing this down in my sketchbook thinking, Oh my gosh, I don’t know anything. But I wrote down three things: cats, Korea and food. But what am I going to do with this? And then I end up making a book about Korean heritage. The first book I did about Korean culture is No Kimchi for Me which was my second book.

STEPHEN: Marshall was so good at meeting people on their level, and you start with those two phrases: Draw what you know,

draw what you love, and don’t worry about it. Start with what’s in your heart and what’s in your mind.

ARAM: It’s so deceptively simple.

STEPHEN: You knew what your goal was, but you had to figure out how you were going to get there. Nobody can tell you how to do that. It’s a lot of trial and error that gets you to that goal.

ARAM: With that book especially, there was a lot of trial and error, and I owe that to my editor in Holiday House, Grace Maccarone. I learned so much about storytelling from her.

Working with Grace, I learned how to boil down the essence of the story, which took me a long time. There is so much that you want to tell, but then there’s only 32 pages. You really need to have focus, and you really need to have a single strong storyline that kids can follow through.

STEPHEN: It was Neal Porter who would tell me I’ve got to get to the idea of the book quicker on page three. Otherwise the reader is so lost.

ARAM: That’s very good advice for children’s book storytelling in general. There’s no long introduction. Everything has to happen fast and you need to get to the problem, you need to serve it, and you need to have a satisfying ending.

STEPHEN: They say an editor is not really your boss but your first reader. They’re going to put themselves in the role of some seven-year-old, six-year-old kid in a library opening your book. If they’re a good editor, they should be able to channel that six-year-old reader.

I want to ask you for some practical advice, and maybe, gosh, this will even help me! But it’ll help anybody who wants to get into children’s books. What should they have in their children’s book

portfolio? Many people don’t know what to include. They don’t even put kids in it! Does it always have to have kids? What should those kids be doing?

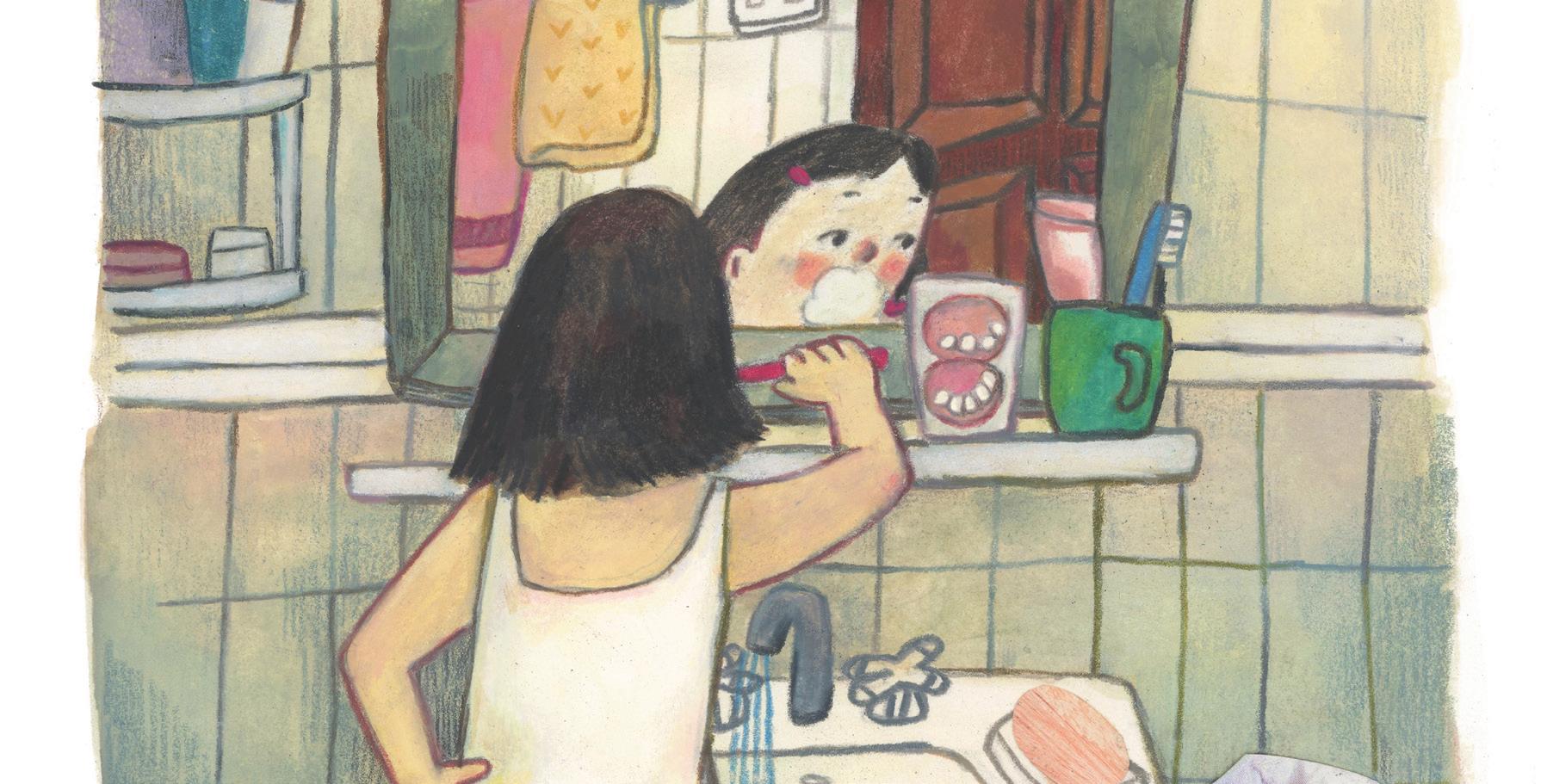

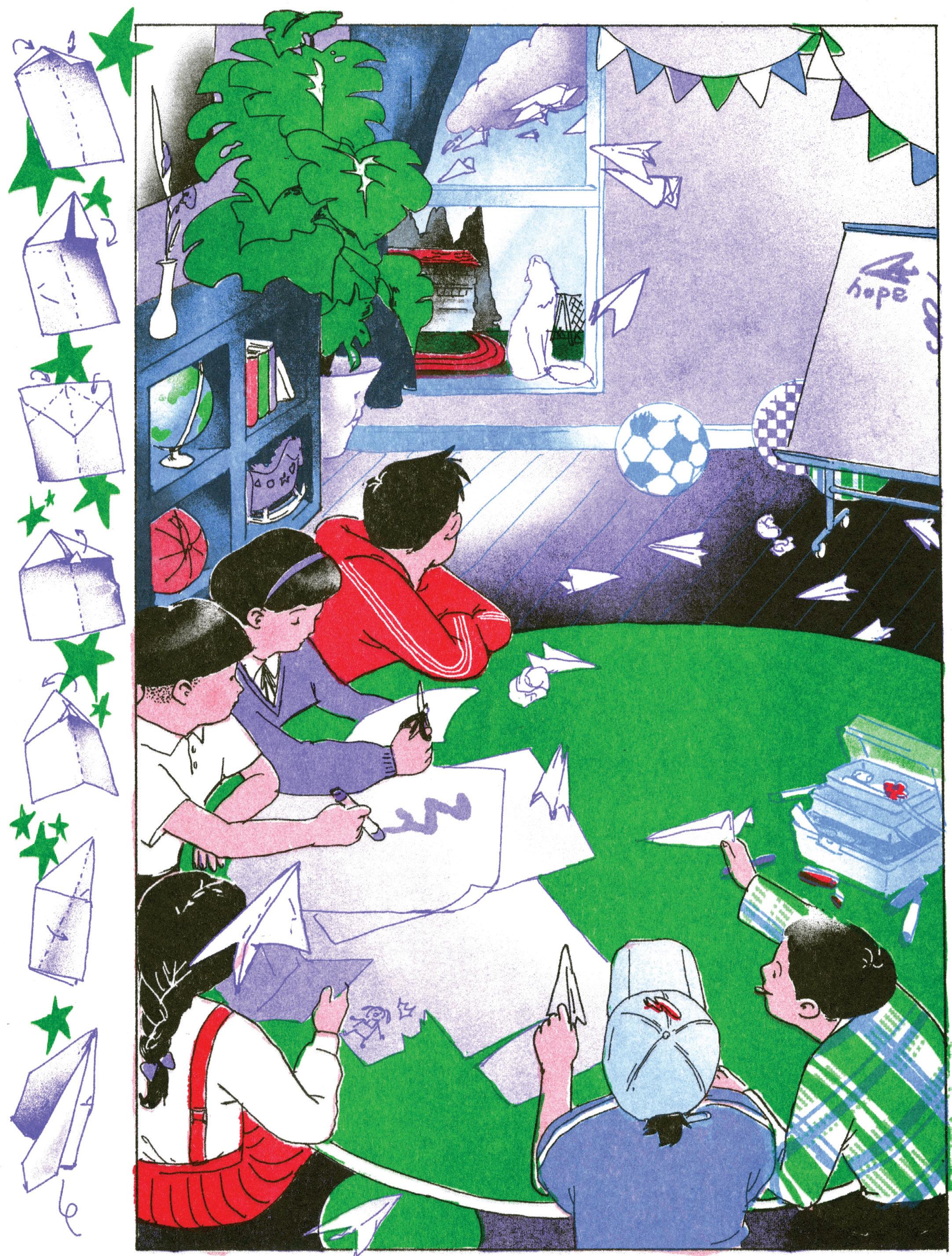

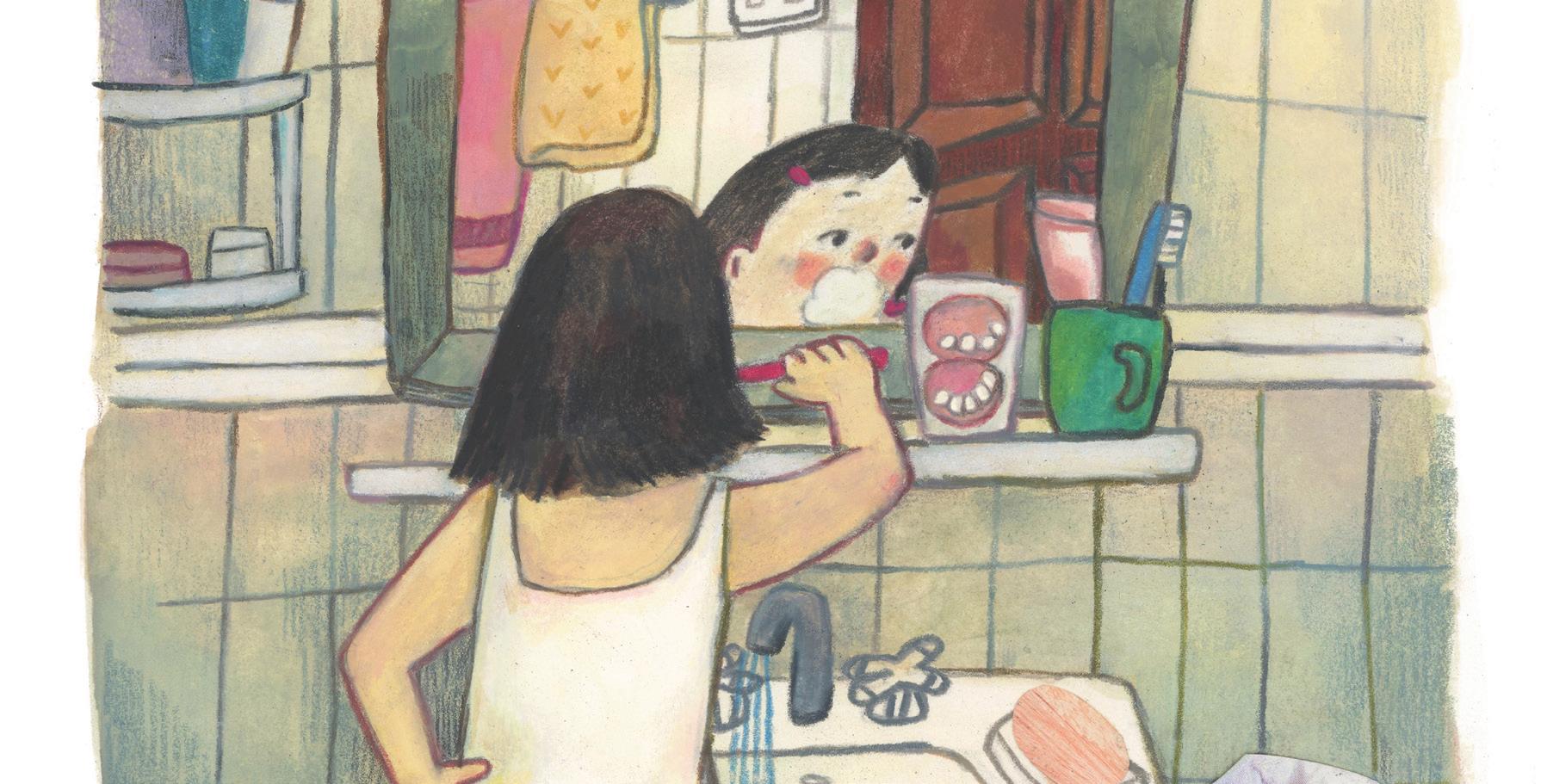

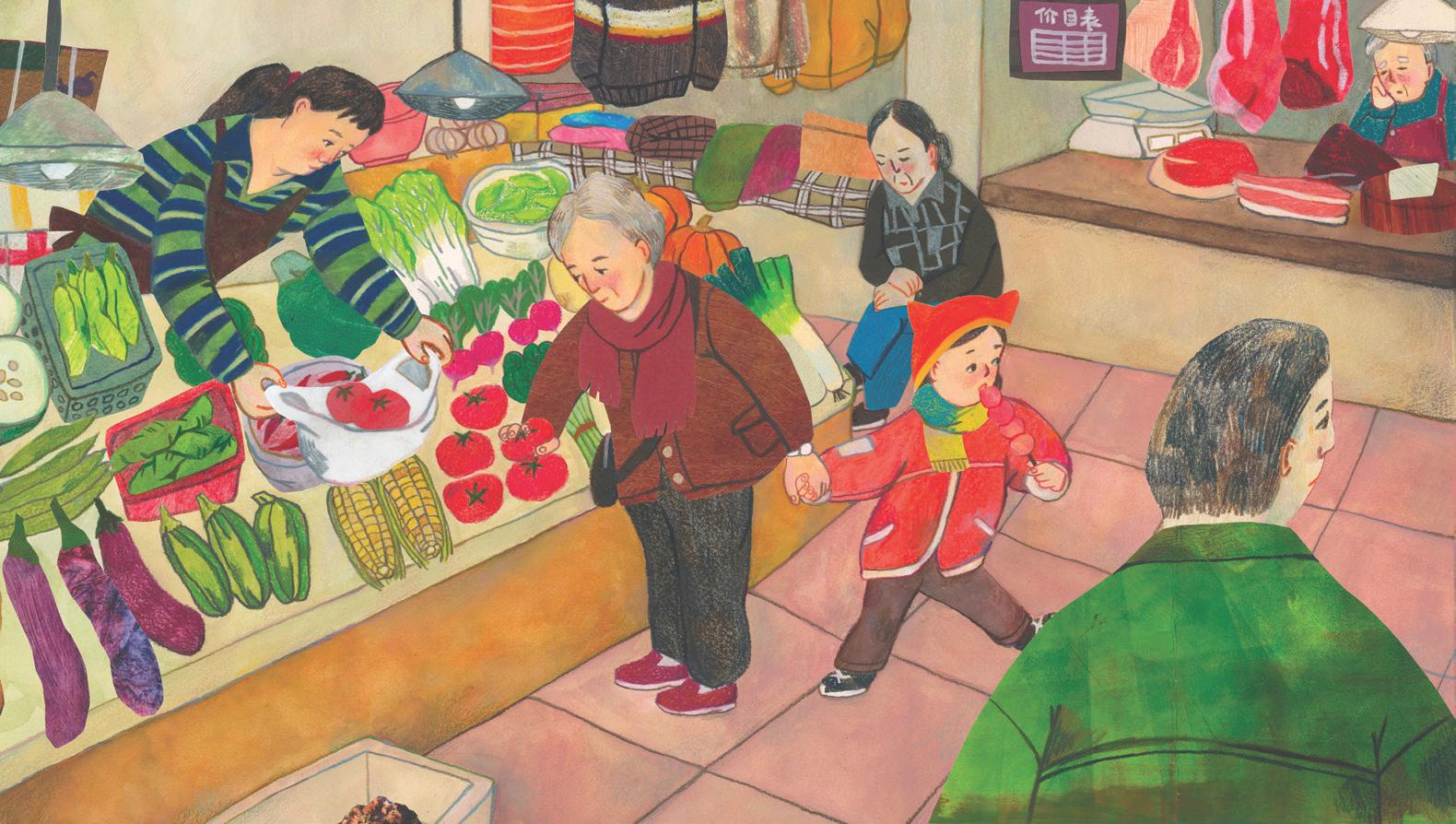

ARAM: I would be super practical. You don’t have to follow this to the letter, but this will make it easier to get into the industry. When pitching, there are a lot of opinions coming from sales and marketing, too, because the book is a product that we need to sell. It’s always much easier if you have a portfolio curated for a children’s book field to be hired as a children’s book illustrator. So yes, kids—because children’s picture books. You need to have an illustration of your target audience—not a portrait but them in action; set them in relation to someone else. If you look at any children’s book, we are not going to see a kid sitting around doing nothing. We need to see them in an environment. I often get portfolios with only character studies, which doesn’t give me confidence that this person can do a full spread of say, a school setting.

If it’s bedtime for the kids, don’t just have a kid in bed. Maybe the kid is having a storytime with one of the caretakers. Ask yourself: What is their body language? What are their expressions? We say the most important thing in a children’s book is emotion. If I look at a piece and don’t know what this kid is feeling right now, then it’s not a successful piece.

STEPHEN: It’s also interesting that in my notes that you gave back to me about Rescue Cat—and, of course, you need to always go back to our conversation about art directing yourself—you asked, “What are my characters thinking and feeling and how do you want the reader to respond to that?”

ARAM: But, Steve, what about you? What kind of advice do you give to your students who might want to do children’s books? What would you say?

STEPHEN: I think the biggest piece of advice is that you can’t do it without knowing what children’s books are. You need to sit down and research these children’s books and get to know them as pieces of literature and approach it as literature.

So many of my students have so many amazing skills, but they’ve got to be telling a story and all these images have to link up. You have to make a 32-page dummy, basically a rough draft of the entire book to see if you can take some loose sketches and create a story that has a beginning, middle and end.

If you’re thinking about going into children’s books, there’s all of this preliminary work that you have to do before you even get to the final art. It’s going to occupy you for probably several years to get right. Your audience should feel like they want to read the book again, a story they’re going to read over and over.

ARAM: Having loose sketches to really tell

a complete story from beginning to end—that is the best practice you can do.

STEPHEN: It’s hard to sit down now and create a dummy that’s 32 pages. It’s excruciating. The blank page is staring you in the face. I don’t know if I’ll ever feel like the sketch process is easy; it’s always the hardest.

Do you get pitched a lot of ideas?

ARAM: I used to get a lot, but not so much anymore because I’ve been making it clear that I don’t accept dummy books.

I accept art samples from anyone because we’re always looking for artists but that’s my boundary. I also don’t acquire books, editors acquire books. So when a pitch comes to me, I feel like it’s a waste of time for both parties because, even if I think it’s a great idea, I’m not going to the acquisition meeting.

STEPHEN: Giving someone a really good

critique on a book means that you’re allowed to read the book and you have to think about it.

Just like all the corrections I have to do this weekend on my next book that came from Aram! But honestly, I can’t wait. I’m excited for a long weekend to work on it. Thank you, Aram. It’s always great to talk to you.

ARAM: Us working together has been great! I’m also so excited about Rescue Cat

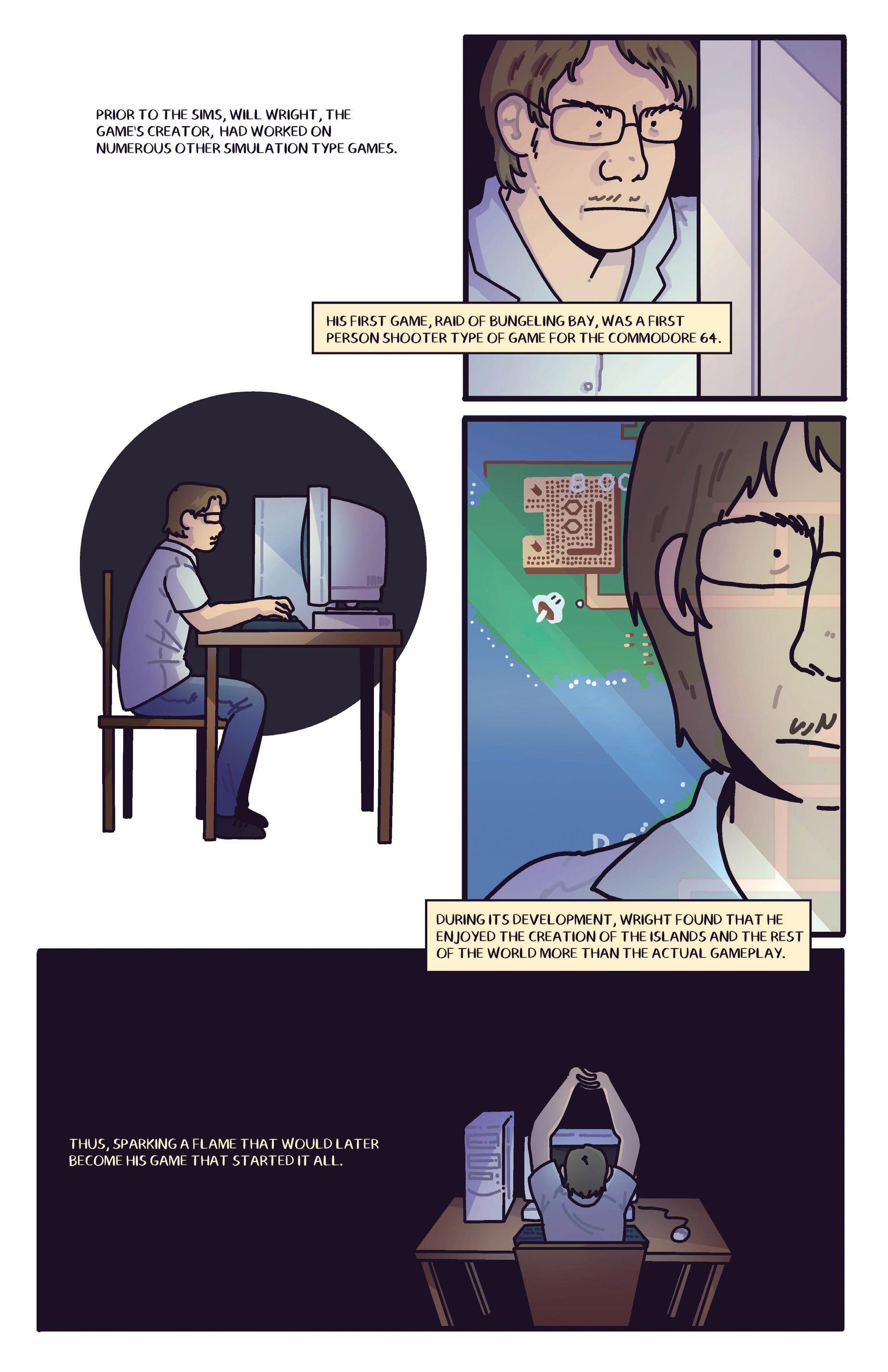

There’s Art, and then there’s Illustration. We are all born artists—many of us were drawing before we said our first words. But only a few of us continue down the artistic path. Making marks as a child seemed natural, drawing pictures—we drew what we saw. In my own experience, the marks I made were merely scrawls on the pages of one of my favorite children’s books, The Little Engine That Could. I was fascinated by the story of the little engine and motivated by the full-color illustrations, which, at the time, were just art to me. In trying to capture the drawings, I saw I made circular ink marks on each page, to the consternation of my mother. It is the only book I remember my mother reading to me, and I can still hear her say, “Don’t you want me to read you another book?” “I think I can, I think I can” was the mantra of the little engine, which has had a profound influence on my journey as an artist, illustrator, designer and art director.

I was never the best artist in grammar school. If the best artist, Harry Miller, was busy doing one poster for class, I got to do the other. He was a big influence; I actually collected his work after projects were finished. I’m certain that, today, Harry is either an accountant, lawyer or a stock trader, as the art he created didn’t mean anything to him—he gave it away freely.

As artists, we love exploring the world around us, observing and recording as best we can. In grammar school, there weren’t art classes, there were no instructors, no critiques—everyone was free to draw whatever they pleased. Yes, there were class projects for Thanksgiving cards or to create Christmas gifts using popsicle sticks but these were just projects; no one was judging whether the outcome was good or bad. Afterall, art is subjective.

The Art of Illustration

BY CHARLES HIVELY

posers—instead, they looked pretty conservative. It’s something that I also observe today when meeting illustrators. Not everyone is cut out to make art as their living, whether it’s fine art or illustration, but everyone who has laid their path as an artist will always be an artist. Creativity is the backbone of all art; making things that matter either individually or professionally can only be accomplished by the creative mind. What makes the difference between fine and applied art is the purpose. The artist’s goal is self-expression. The illustrator’s main purpose is communicating a message, imparting information in an interesting way.

While illustration is an art, not all art is illustration. Artists can create whatever they like, whenever they like. Illustrators are given assignments, briefs and deadlines. Other creative fields offer some respite, i.e., if an art director didn’t come up with any new ideas today, they won’t be fired. Illustrators are put under pressure, especially in the editorial realm, with three- or four-days max to come up with the idea and execute it. And if the idea fails, the artist fails. As opposed to being a fine artist where failures go unmarked.

The typical picture of the artist is alone in the studio making art. And while many may start out that way, soon there will be assistants to help with creating the final work. Not so with illustrators. Illustrators live a solitary existence, many have started out working on the kitchen table, or a corner of the living room or bedroom. No studio. No studio mates. No assistants.

As young drawers—the description “artist” seems a bit premature—we drew for pleasure. We copied comics found in the Sunday funnies, or drew airplanes, battleships, princesses, or whatever we fancied. We did it on lined notebook paper, cardboard, even envelopes that were lying around. The materials didn’t matter, Crayolas, ballpoint pens or pencils were always at hand. I loved Crayolas, the smell especially, and insisted my parents buy me a new box every year—mostly because I had used up the black crayon—but also because there was something special about getting brand new “tools.”

Moving onto college, the challenges increased; to be an artist wasn’t easy. Drawing turned from a pleasure into a task that needed to be completed in a much more professional way. There were live models, still lifes, plaster casts—all meant to give us a definitive subject to try and capture on our pad. There were a great many avenues to explore and a world of tools at our disposal. Going to class was a joy; there was always something new to learn or to be exposed to. There were artist visits.

I remember one in particular when the artist Lee Krasner came to our class. What I started to notice was that the really good artists didn’t look like the stereotypical artists—scruffy, unkept

During our monthly portfolio reviews at 3x3 magazine, I get to meet artists at all levels. Our 30-minute sessions allow us to explore why they want to be illustrators and what they contribute that no one else can. Illustration is like fashion, there are always trends, trends I’ve experienced since founding 3x3 in 2003. And like fashion, trends go in and out of style. What was prevalent in 2003 is not in 2023. Illustrators are hired based on their personal voice, also known as style. In the United States, and in most of the world, it’s a singular style that identifies how the individual sees the world and how the world sees them. Gaining a distinctive style is no easy task. It helps being open to personal experiences, to your cultural background, to literature and music—all can help define you as an illustrator. Having broad experiences—either naturally, through classes or through books—better enables an illustrator to solve visual problems; it’s the chief criteria for a successful career.

Being successful in any career is not easy, but it is especially hard for illustrators. Let’s define success: it’s the ability to make a living as an illustrator. But beware: illustration assignments do not come with any regularity. Many talented illustrators have second or third jobs to make ends meet. So how do you succeed? Part of it is luck—let’s be honest—and part of it is talent, part of it is self-promotion, and a big part of it is having a champion, some art director or editor or publisher who fancies your work.

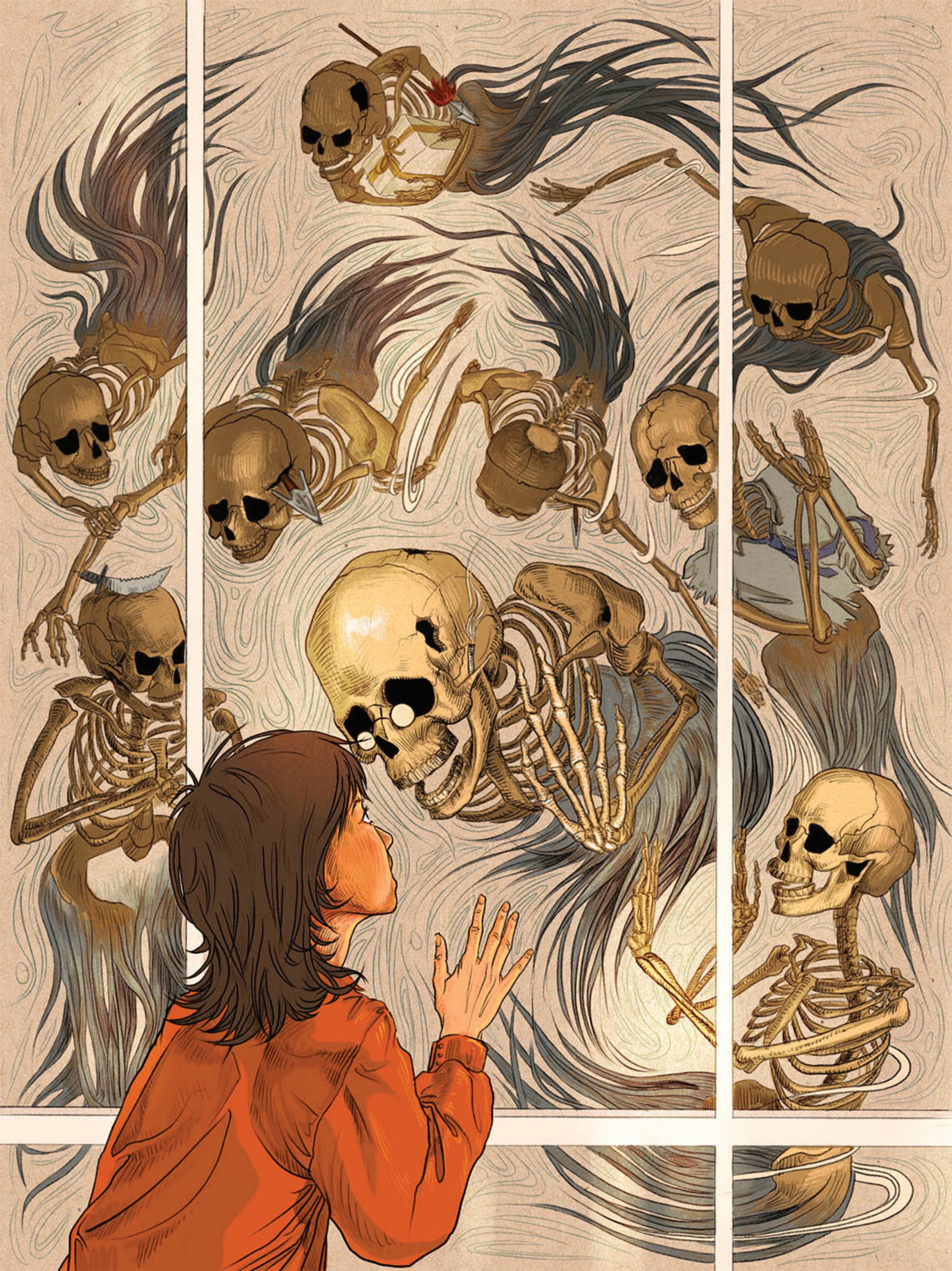

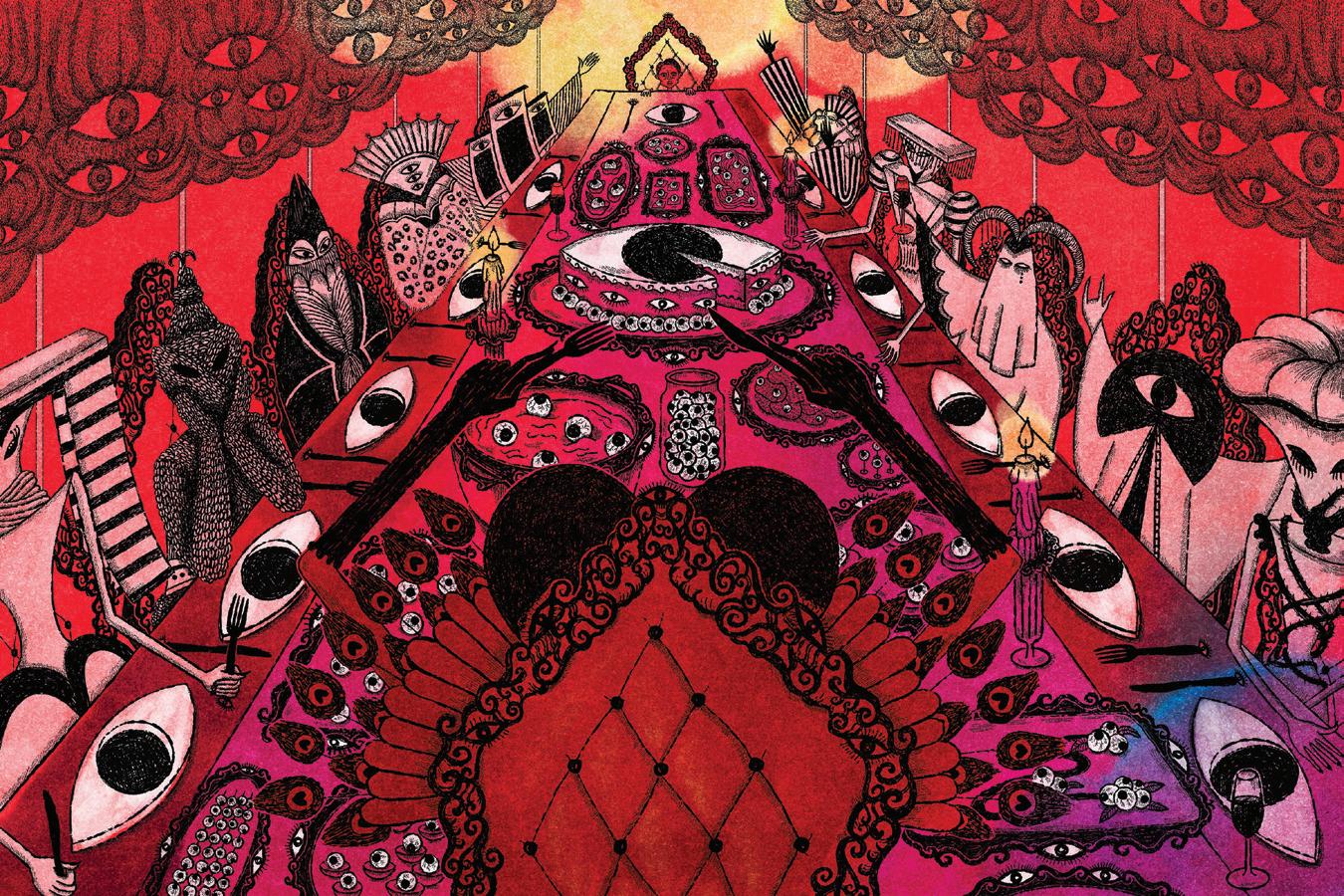

[1]

Illustration is a highly competitive field. I’ve found every graduate wants to be either an editorial or children’s book illustrator or sometimes both. It’s important to seek out other opportunities to use your illustration skills beyond what you may think you know. No matter which area of illustration you choose, it is an art practice where quality is crucial—quality of approach, quality of drawing, quality of concept or storytelling. You can be a good illustrator with quality alone. But to be a great one, you need both quality and significance—your work must stand head and shoulders above what’s already out there. It’s not an easy task to be an illustrator, but be an artist first, then decide which is the best fit for you.

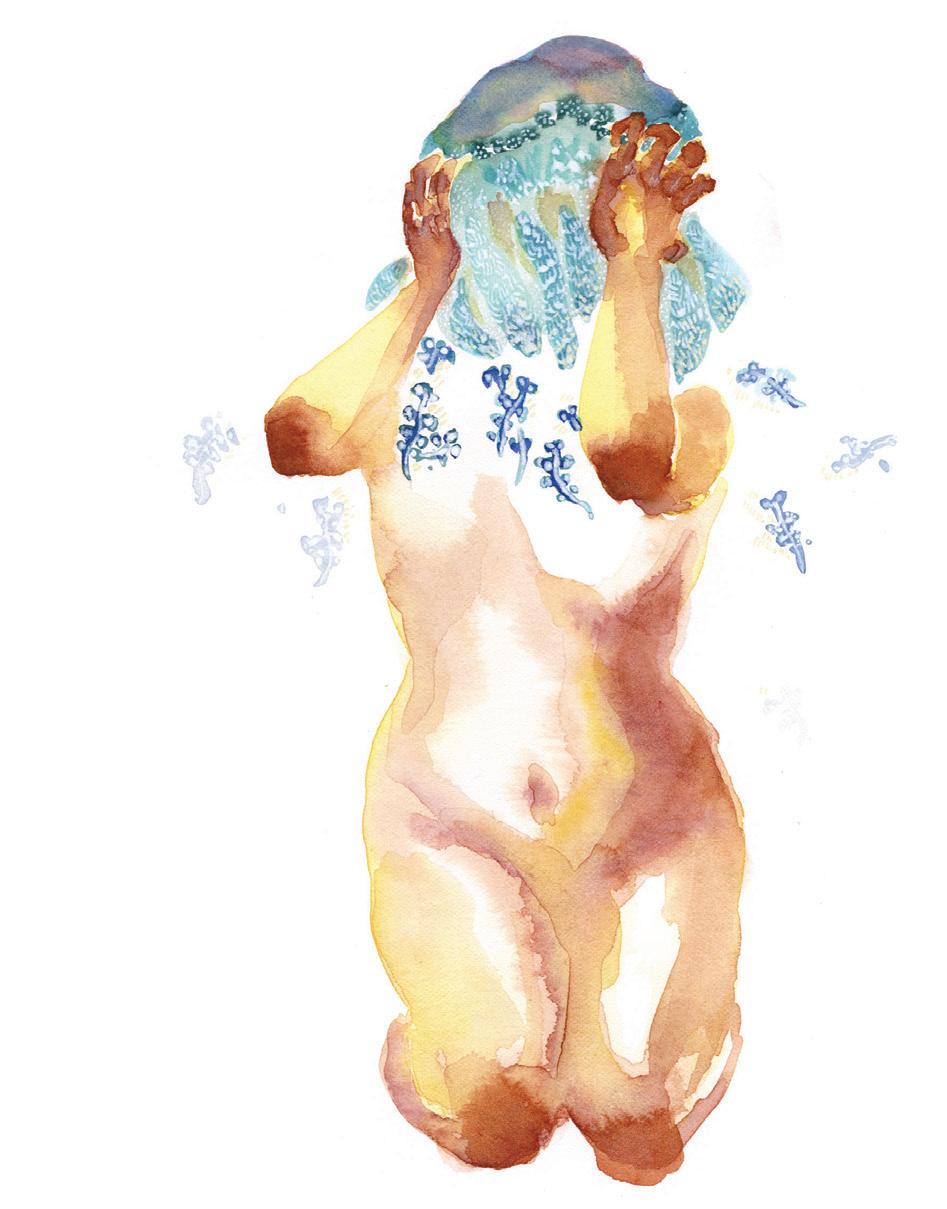

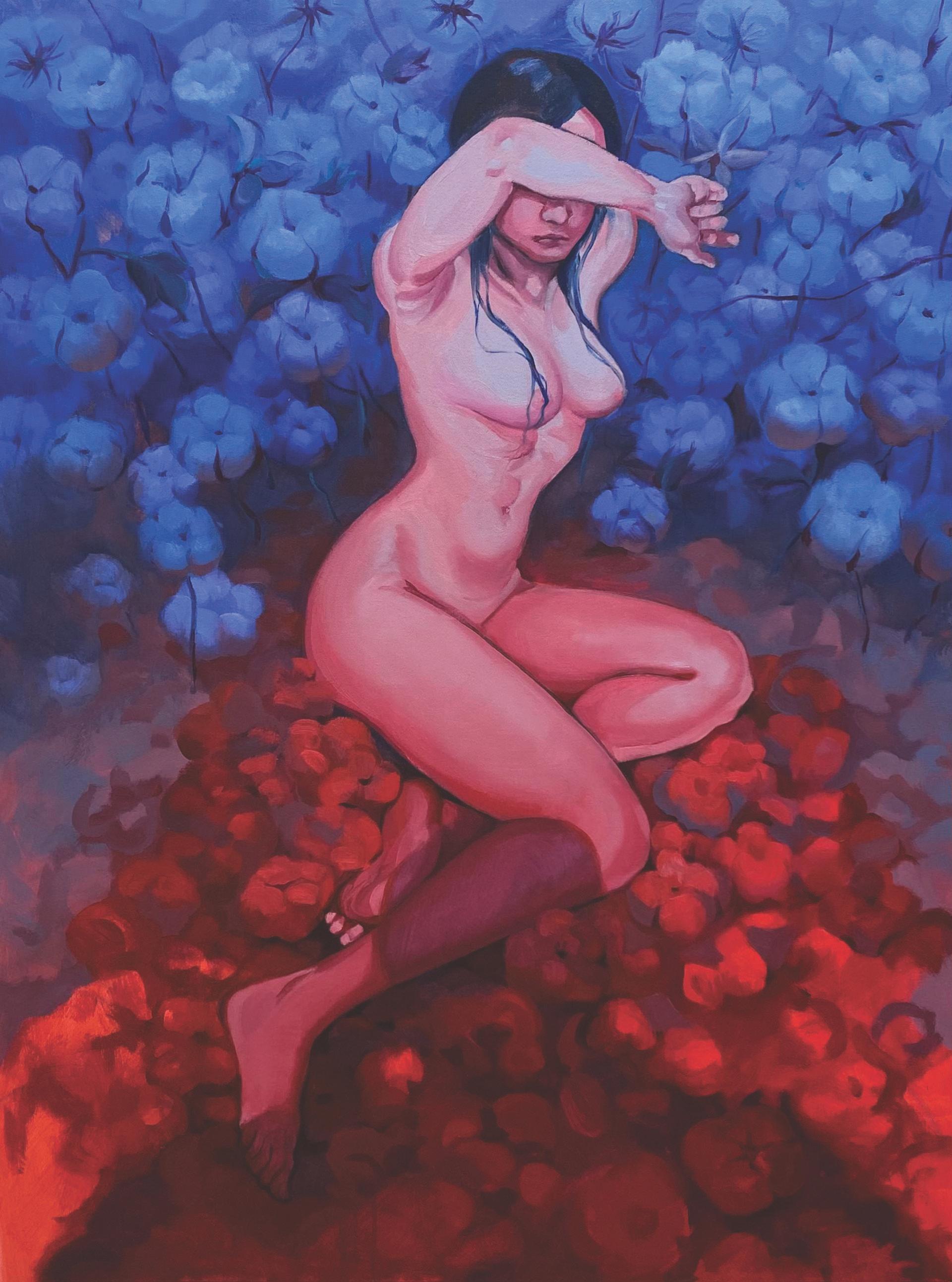

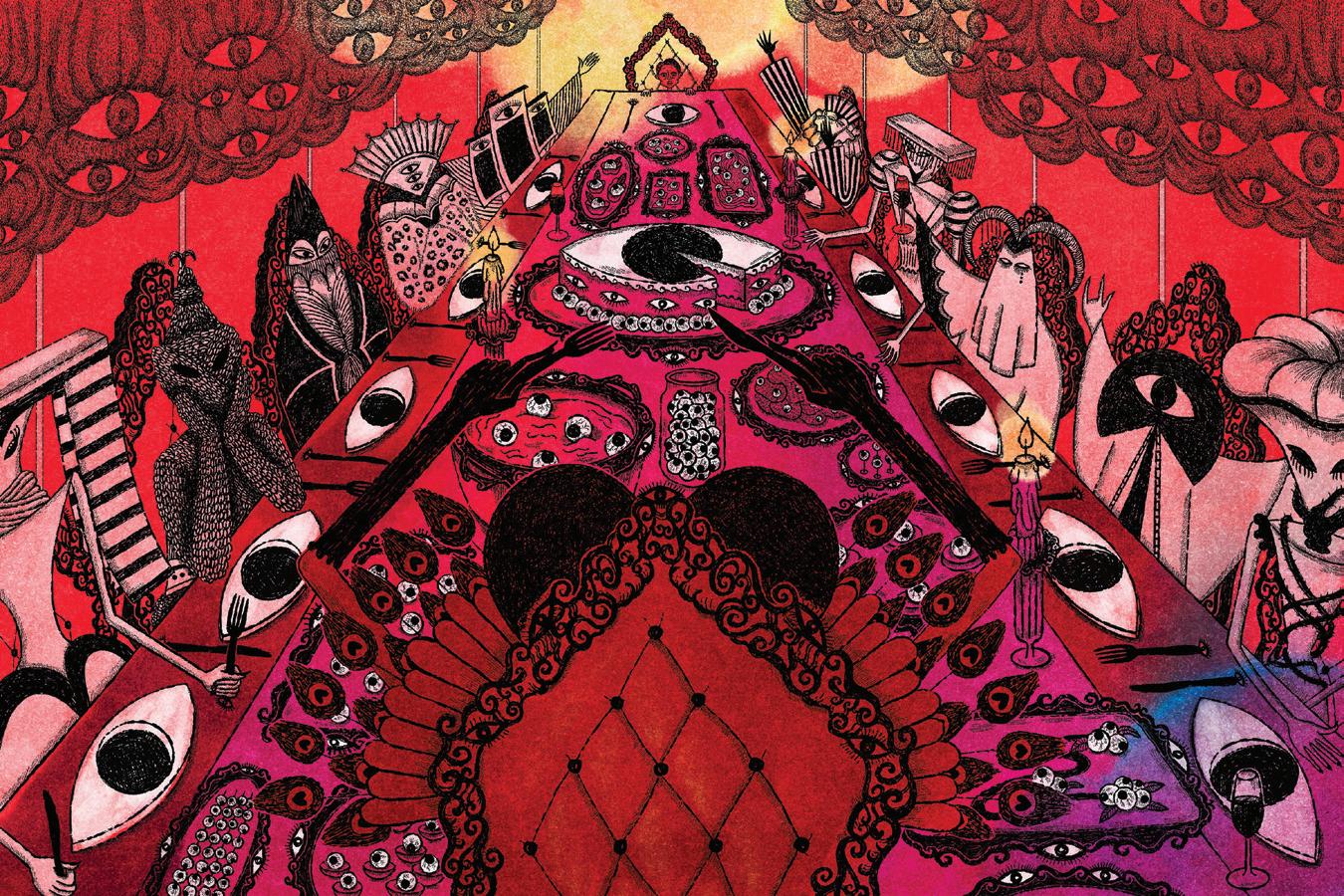

[1] Katherine Lam

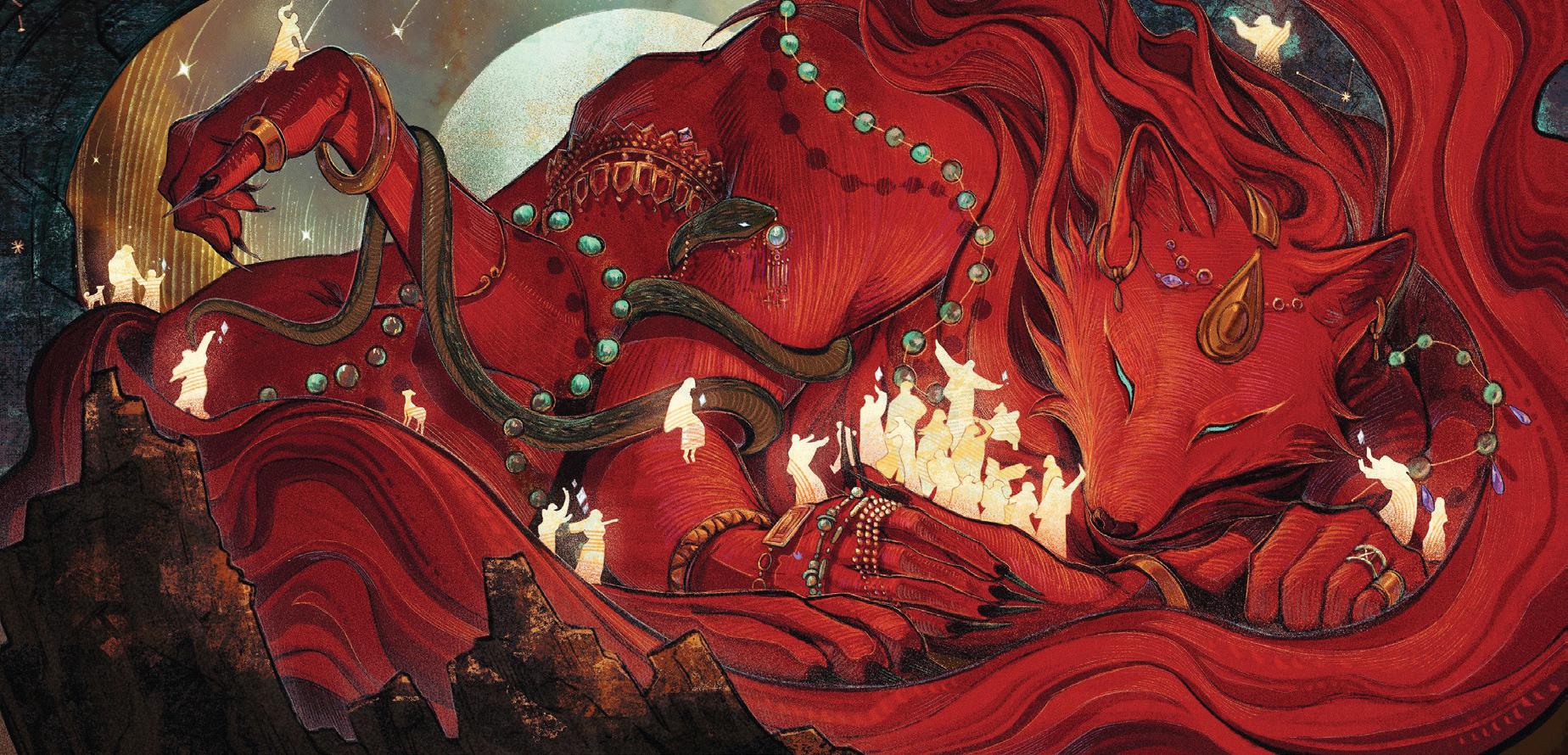

[2] Feifei Ruan

[3] Katherine Lam

[4] Keith Negley

[5] John Han

[3] [2] [4] [5]

There is a quote from Ira Glass, host of This American Life on NPR, that I heard years back and I still think about now when I get stuck in my head feeling unsatisfied with the work I am making.

“All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But there is this gap.

For the first couple years you make stuff, it’s just not that good. It’s trying to be good, it has potential, but it’s not. But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer. And your taste is why your work disappoints you.”

—Ira Glass

The quote continues to say that what makes creative people different from everyone else is that rather than quit, an artist will take the years of struggle, of disappointment, of self-doubt, and continue to make work that eventually matches their innate taste level, and this only comes from making a lot of work. It is a marathon, not a sprint.

Technology has evolved, industry has shifted, but there will always be someone who wants to get better in order to scratch that specific itch at the back of our brains. But probably what struck me most about what Ira Glass said, what it really meant, was that with time and practice and hard work, my skill level would come closer to my taste level. There wasn’t any trick or quick answer, I just had to do a lot of work and be mindful of my practice. It is from that struggle and hard work that rewards in the most fulfilling way, in a way technology could never shortcut through. The artist you are when no one is watching, the skill you learn so that no one can look and want nothing more than to reverse-engineer how it was made. The trickier part, the part that Mr. Glass doesn’t explain is that learning is lifelong, and the likelihood that artists will ever create work that matches their own expectations of themselves is very slim. So rather than plateau, we could think of creating as a marathon against ourselves, and, once the race is over, we can start training for the next. We all know of the courage it takes to make a career out of art and that includes overcoming self-doubt and intrusive thoughts as you practice your craft.

Short BFA Comics Coordinator BFA Comics/BFA Illustration

CREATING AS A MARATHON

Kelsey

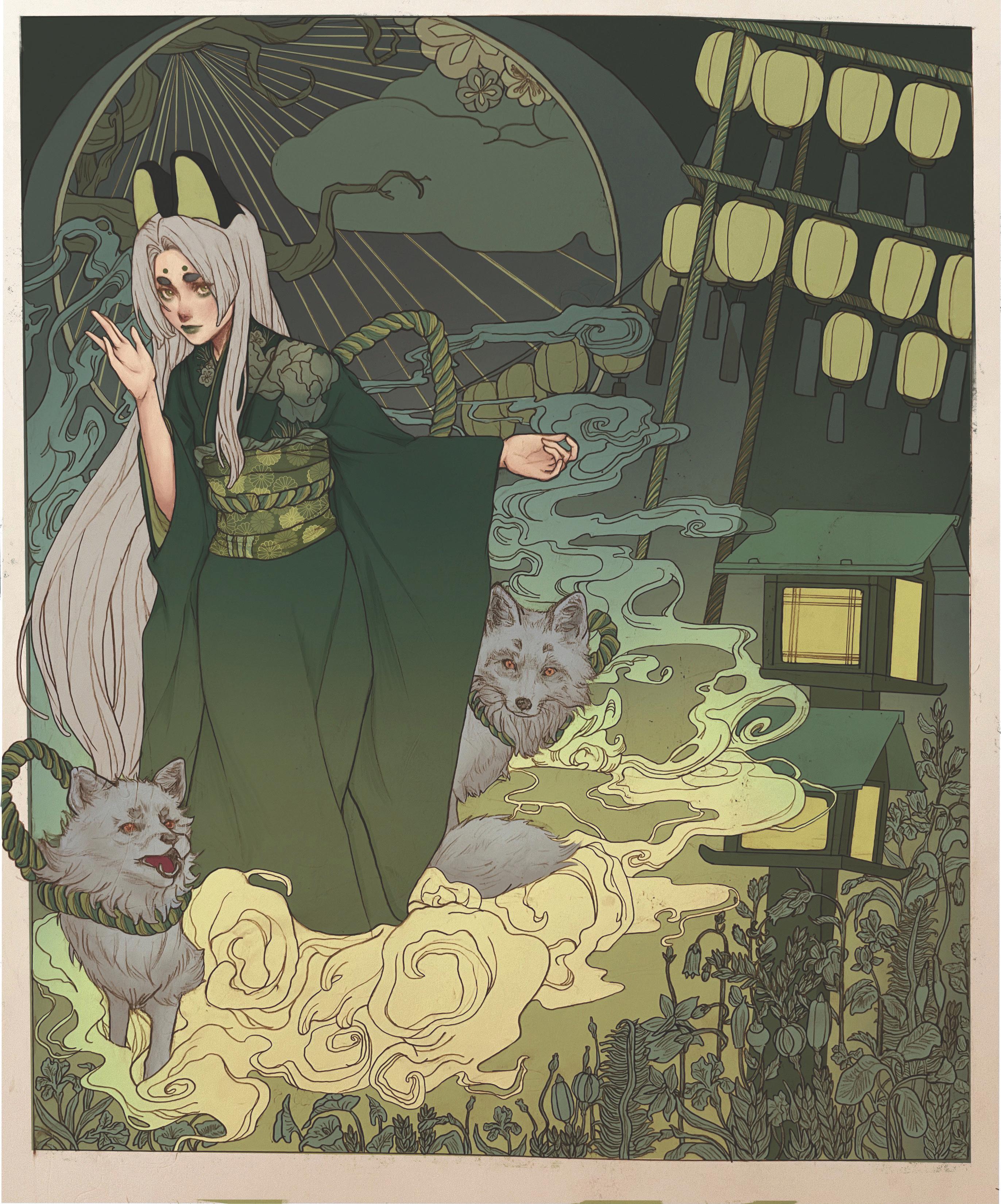

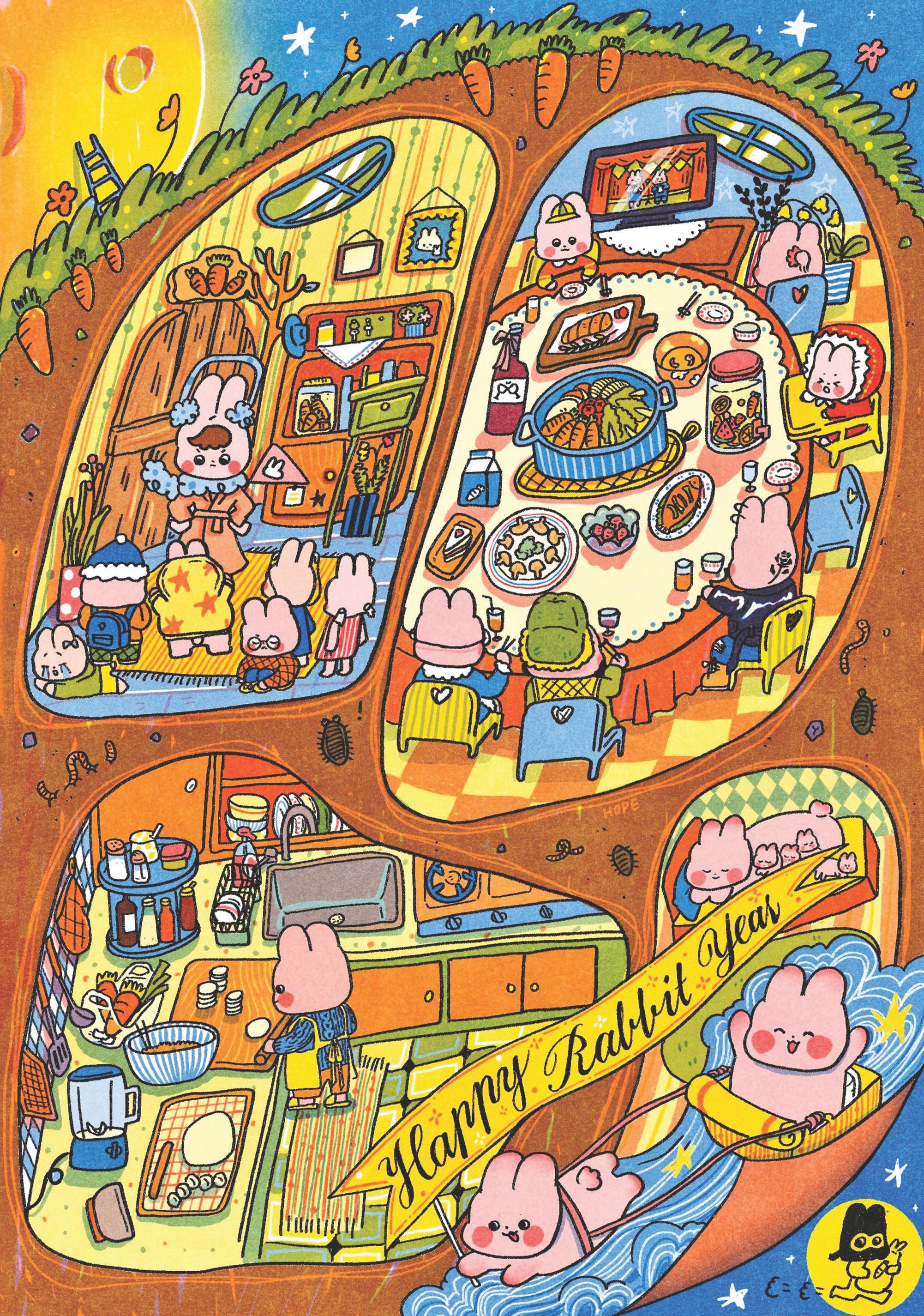

2023 BFA ILLUSTRATION Portfolio Selections

22 23

Chen YUNYAOCHEN.COM

Chen @ALLLY_CHEN

Yunyao

Jiaxi

24 25 Letao Sun LETAOSUN.COM

YIILLUSTRATIONS.COM

Yi Chen

26 27 Xi Jin Mifei Zhou MIFEIZHOU.COM

28 29 Yawen Hu YAWENH.COM

Huang XINNART.COM

Xin

30 31

RYE676.WIXSITE.COM/RYERZ

@SUEEE_YANG

Rongzhang Ye

Songer Yang

32 33 Yutong Du Yinghao Lin YINGHAOLIN.ARTSTATION.COM

34 35

HAOCHENWANGARTS.CARGO.SITE Jenna Park JENNA-RT.COM

Haochen Wang

36 37 Wenbo Wu WENBOWU.COM Sirui Zou RISHALE.CARGO.SITE

38 39

OLIVERILLUSTRATION.COM

Oliver Perry

BELENMARIART.SQUARESPACE.COM

Maria Bautista Signorini

40 41

Liu WWW.RUOSHUILIU.COM

Ruoshui

EUGENEHUANGART.COM

Yujing Huang

42 43 Xiaozhu Cui

Wang ARTBYSAMANTHAWANG.COM

Samantha

44 45

QINGRU-ART.COM

MUTONGLIU.WIXSITE.COM/MLIUARTWORKS

Qingru Yang

Mutong Liu

46 47 Yuxin Ding STELLADYX.COM Yiyang Liu YLIU60.WIXSITE.COM/MY-SITE

48 49

Chen U2602B118.ARTSTATION.COM

Xinyun

@LIGHTERZYH

Yuhe Zhuang

50 51

Guo GXHART.COM

Zhang @EMILY_XYUZ

Xiaohan

Xiaoyu

52 53

Yiwei Wang

YIWEIWANG.ORG

Lutong He CHERRYLUTONGHE.WIXSITE.COM/MY-SITE

54 55 Jihae Park HAE-CHERRIES.ART

@JUICEBOX.ART

Zachary Guzman

56 57

LONGLINT.WEEBLY.COM

HUAIXUANXIANG.COM

Long Lin

Huaixuan Xiang

58 59

DAMMIDRAWS.COM

Damian Gary

Kiddo CTIAN2.MYPORTFOLIO.COM

Emo

60 61 Emani Simons EMANISIMONS.UNIVER.SE Ella Shi ELLASHI.COM

62 63

NINGJIANGART.COM

Ning Jiang

THELOUIEMARTIN.COM

Louie Martin

64 65 Ria Varma RIAVARMA.COM Timo Chou TIMOTIMO628.COM

66 67 Yubin Lee EELNIBUYART.COM Ji Ling Wu Li

68 69

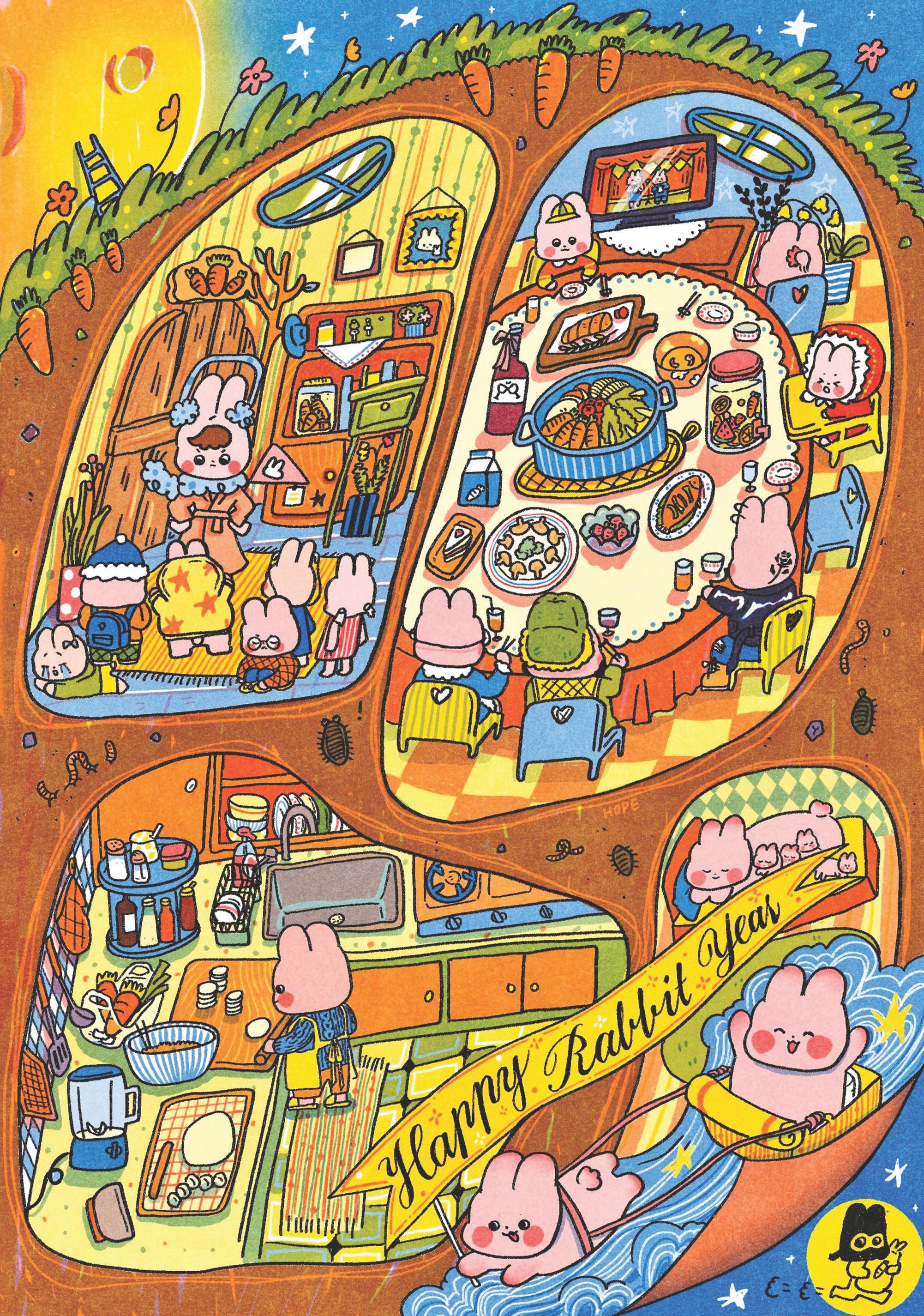

Xi HOPEXI0101.COM

Hope

PXKAT_ART.ARTSTATION.COM

Justin Jung

70 71 Yiyang Yvonne Li Le Cong Nguyen Nguyen TIGERLILIKO.COM

72 73

Chan JASMINE-CHAN.COM

Yang HANYUYANGART.COM

Jasmine

Hanyu

74 75

Zhang @EXTRACILANTRO_

Dong YIJIANGDONGART.COM

Yueyi

Yijiang

76 77

Jingyi Cai

Laís Rojas

78 79

Mckenzie

Zhihan Zhang

Jones MJONES242.WIXSITE.COM/MCKENZIEJONES-ART

80 81 Alana Green ALANAGREENART.WIXSITE.COM/SITE Wenjun Shao @YANSHIANO

82 83 Huilin Gui HGUIDRAWS.WIXSITE.COM/HUILIN

Lauren Giancola

84 85

@CARBODRAWO

Carolina Gajardo

VIVIANLIANG.ORG

Vivian Liang

86 87 Verum Zhou VERUMZHOUART.COM

88 89 Ariel Miner ARIELMINERART.COM

90 91 Denise Alayón DENISEALAYON.MYPORTFOLIO.COM

92 93 Jehao Wu JEHAOWU.COM

94 95

Vinay CHERRYANDSISTERS.COM

Mansi

96 97

MAXINEYULINGZHOU.COM

Maxine Zhou

98 99 Jingyao He @JYAO_KATIE

100 101 Sunny Ruan SUNNYRUANARTS.CARGO.SITE

102 103

JIMZLIANG.COM

Jim Liang

104 105 Yiwen You

106 107 Yilin Zhu YILINZHUPORTFOLIO.COM

BFA

•

•

COMICS

2O23

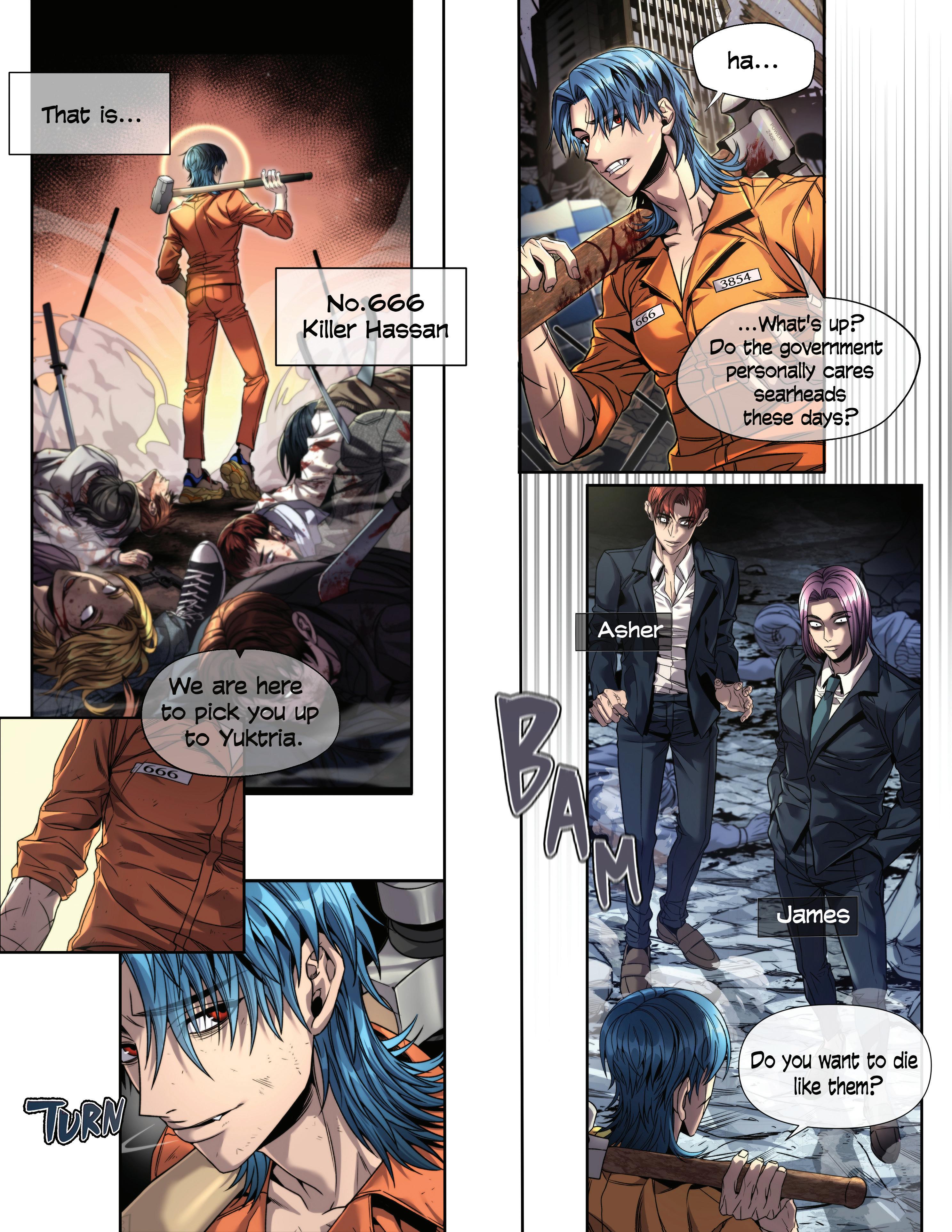

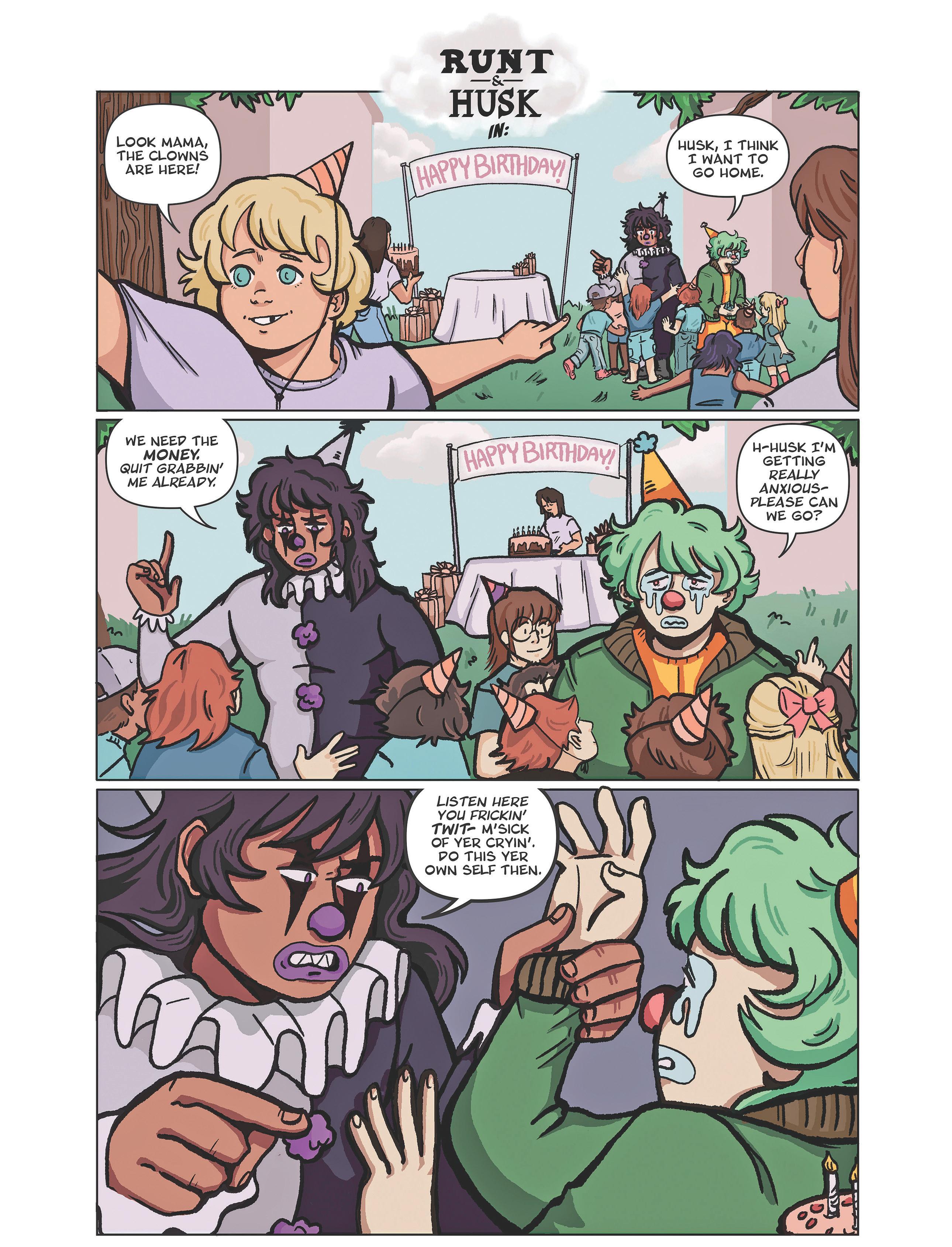

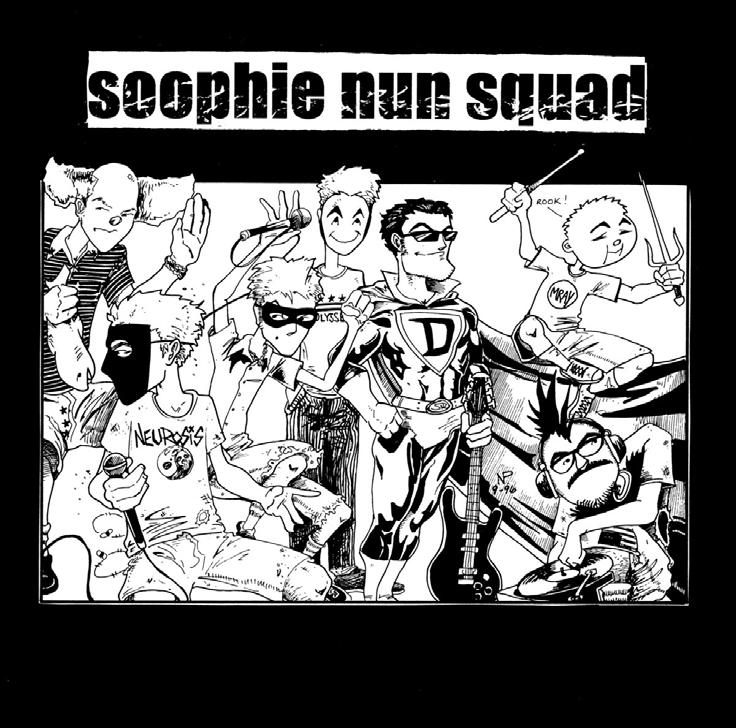

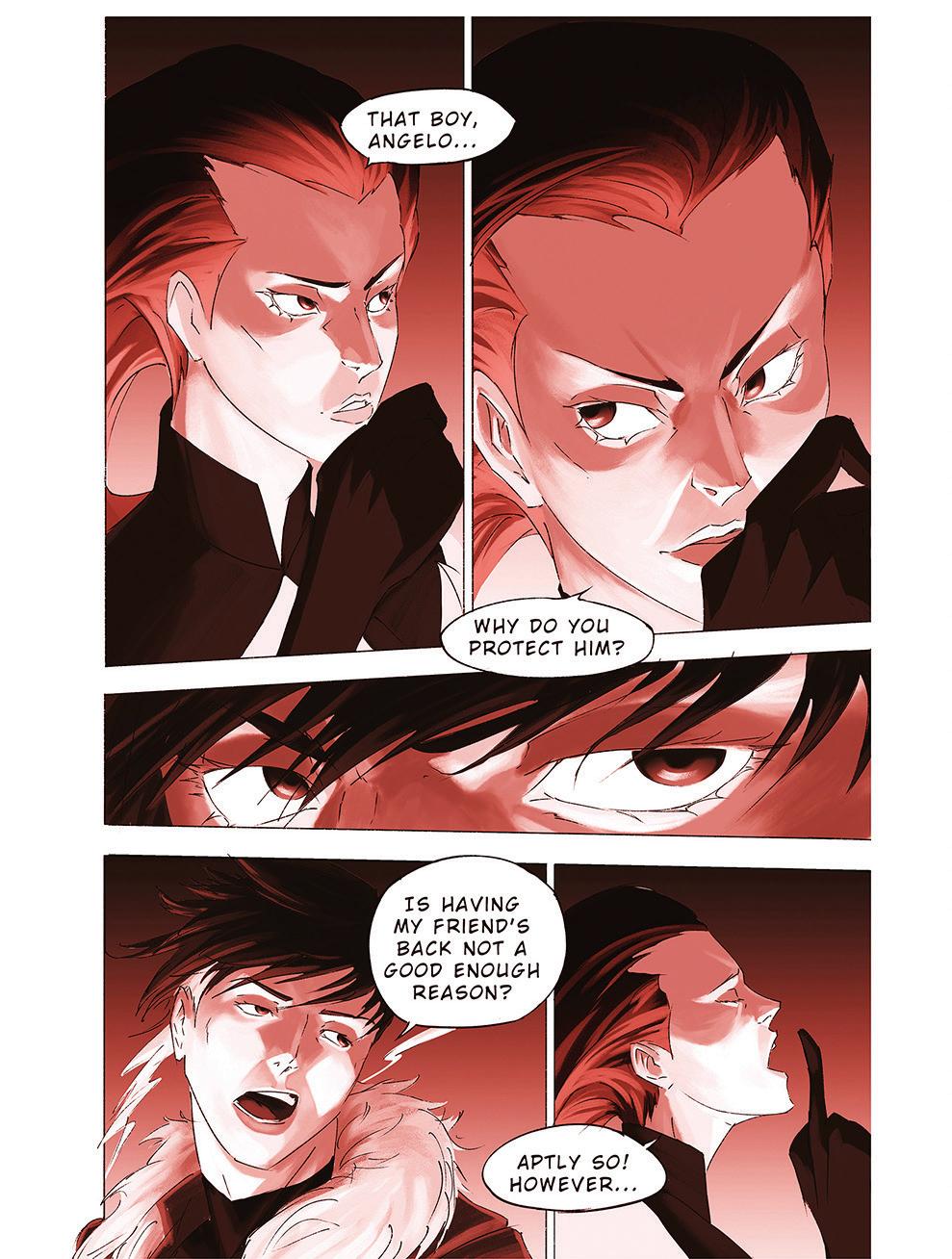

Seventy-five years ago, Silas H. Rhodes and illustrator Burne Hogarth (Tarzan) co-founded the Cartoonists and Illustrators School with New York City–based art professionals as faculty. Reflecting the belief that there is more to art than technique, the institution changed its name to School of Visual Arts in 1956.

The BFA Comics Department’s direct lineage to this long legacy manifests itself in our legendary faculty that, through the years, has included artists such as Will Eisner, Harvey Kurtzman, Art Spiegelman, Jessica Abel, Gary Panter, David Mazzucchelli, Bill Griffith, Diane Noomin, Klaus Janson and distinguished alumni like Wally Wood, Steve Ditko, Peter Bagge, Kyle Baker, Ray Billingsley, Leslie Stein, Becky Cloonan, Raina Telgemeier, Dash Shaw, Nate Powell and Molly Ostertag.

The department has significantly contributed to the changing perceptions towards this entire genre of storytelling. Just look at the comics industry today—its publications (creative process and distribution), conferences and festivals in the last 30 years (I was hired by Marvel Comics in 1992). Consider everything from analysis-driven academic symposiums to independent events like MoCCA or SPX, the big Comic Cons in San Diego and New York, and the plethora of smaller, grassroots comic book events. By examining all these elements of the industry, one easily realizes that comics is not only a powerful business with some of the most devoted fans, but it also has established itself as a deeply respected language of sequential expression, an artistic discipline, a field of study and a career path.

Our 2023 edition of ILLO showcases notable senior accomplishments, representing but a tip of the iceberg for the ink, sweat and tears that go into this process speech bubble by speech bubble, frame by frame, page by page. To accompany this visual, celebration we also commissioned critical essays and interviews between respected SVA faculty mentors and alumni they’ve impacted.

This introductory note would be incomplete without recognizing the many talents going into a publication like this, from our gifted students to our long list of outstanding faculty and our department team. Thank you to SVA President David Rhodes for his trust, meaningful guidance and ongoing support. I am deeply grateful to the tireless Carolyn Hinkson-Jenkins, Matthew Bustamonte, Jason Little, Kelsey Short, Heaven Boles and their passion for this project, their ideas, and care in introducing our brilliant 2023 graduating class to industries they are about to deeply transform.

As challenging as it is to crystallize the spirit of a department and provide a tangible memento of the work, talents and spirit that make BFA Comics tick, this publication will come very close.

Viktor Koen Chair BFA Comics BFA Illustration Chair

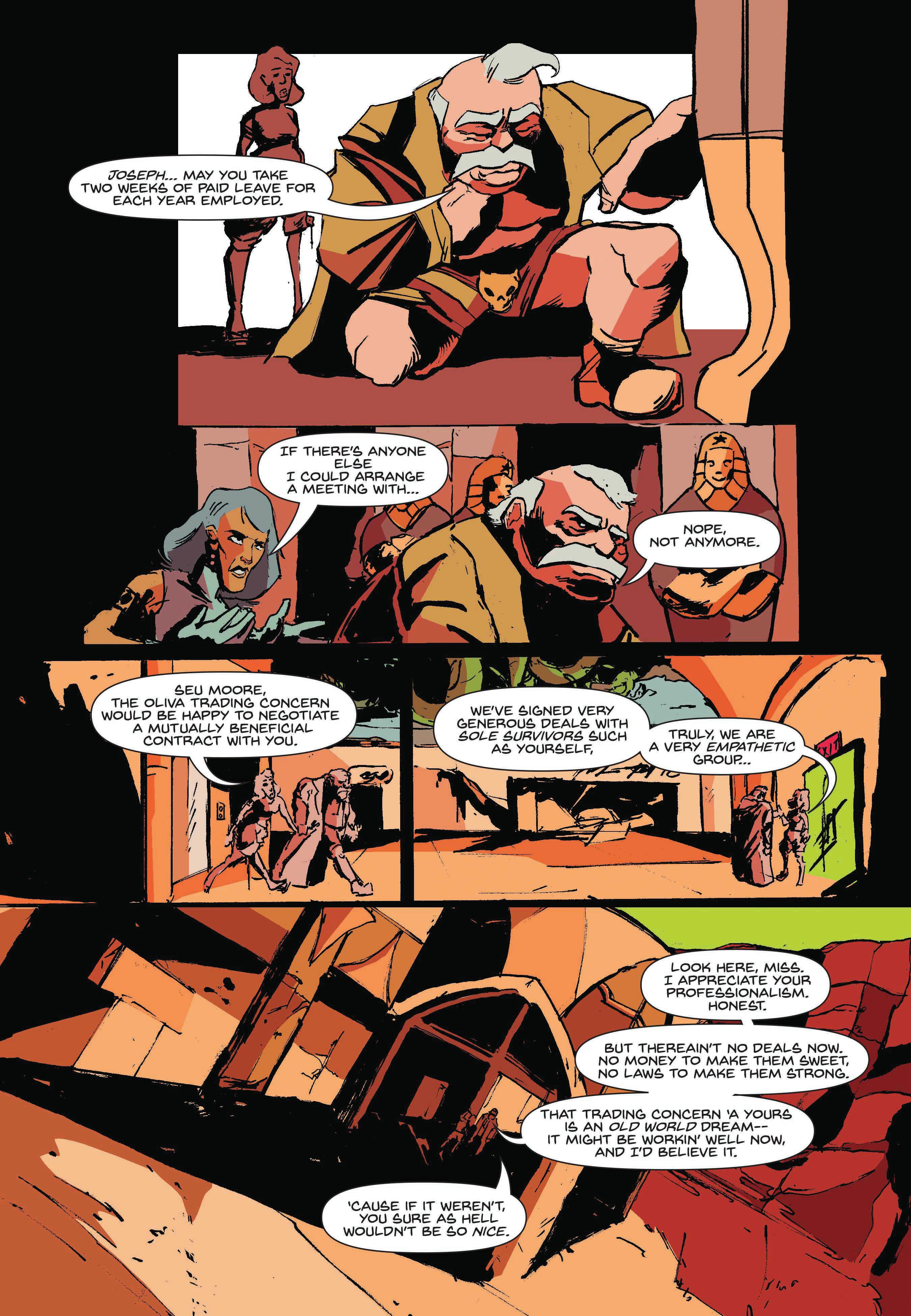

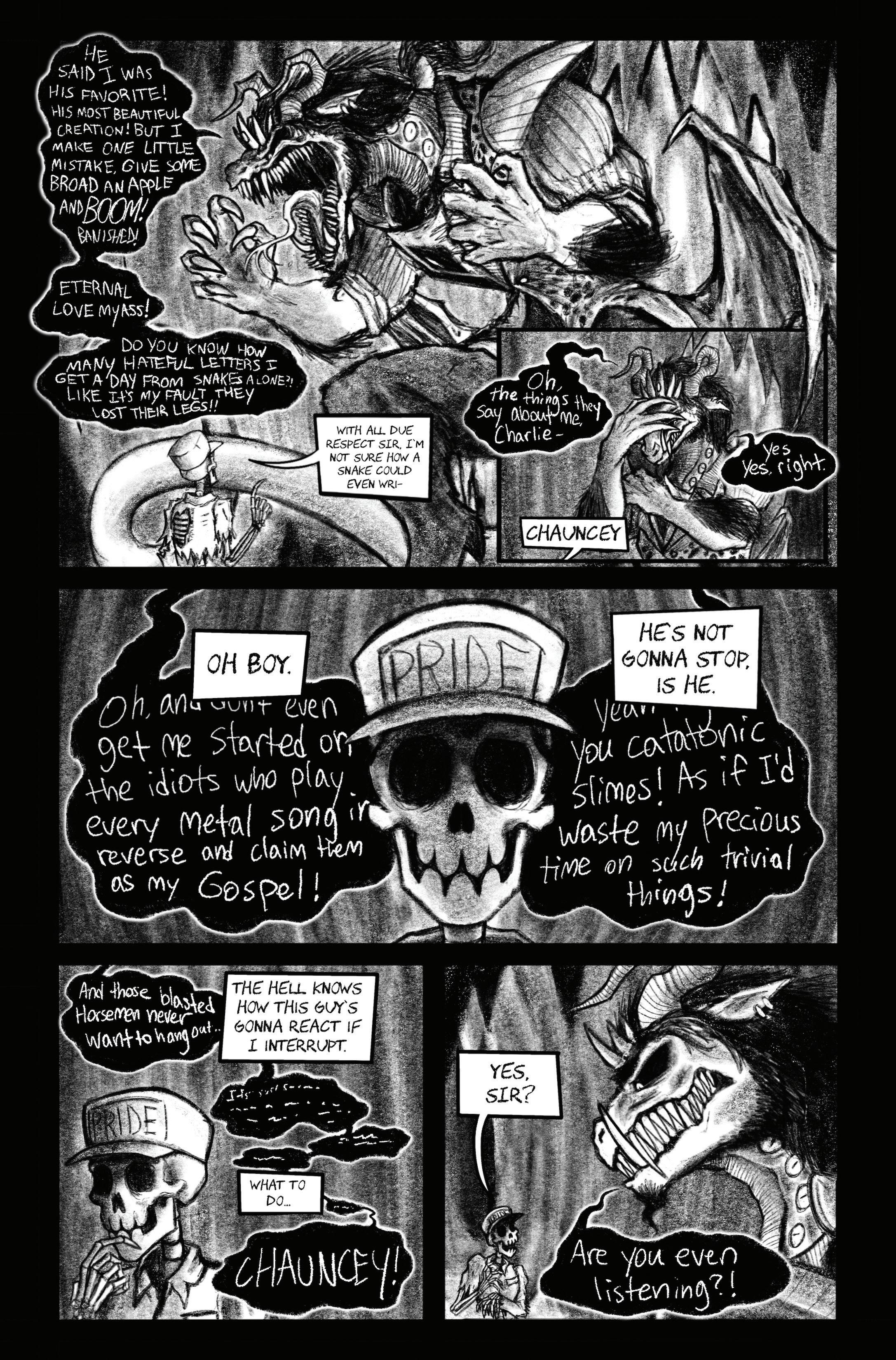

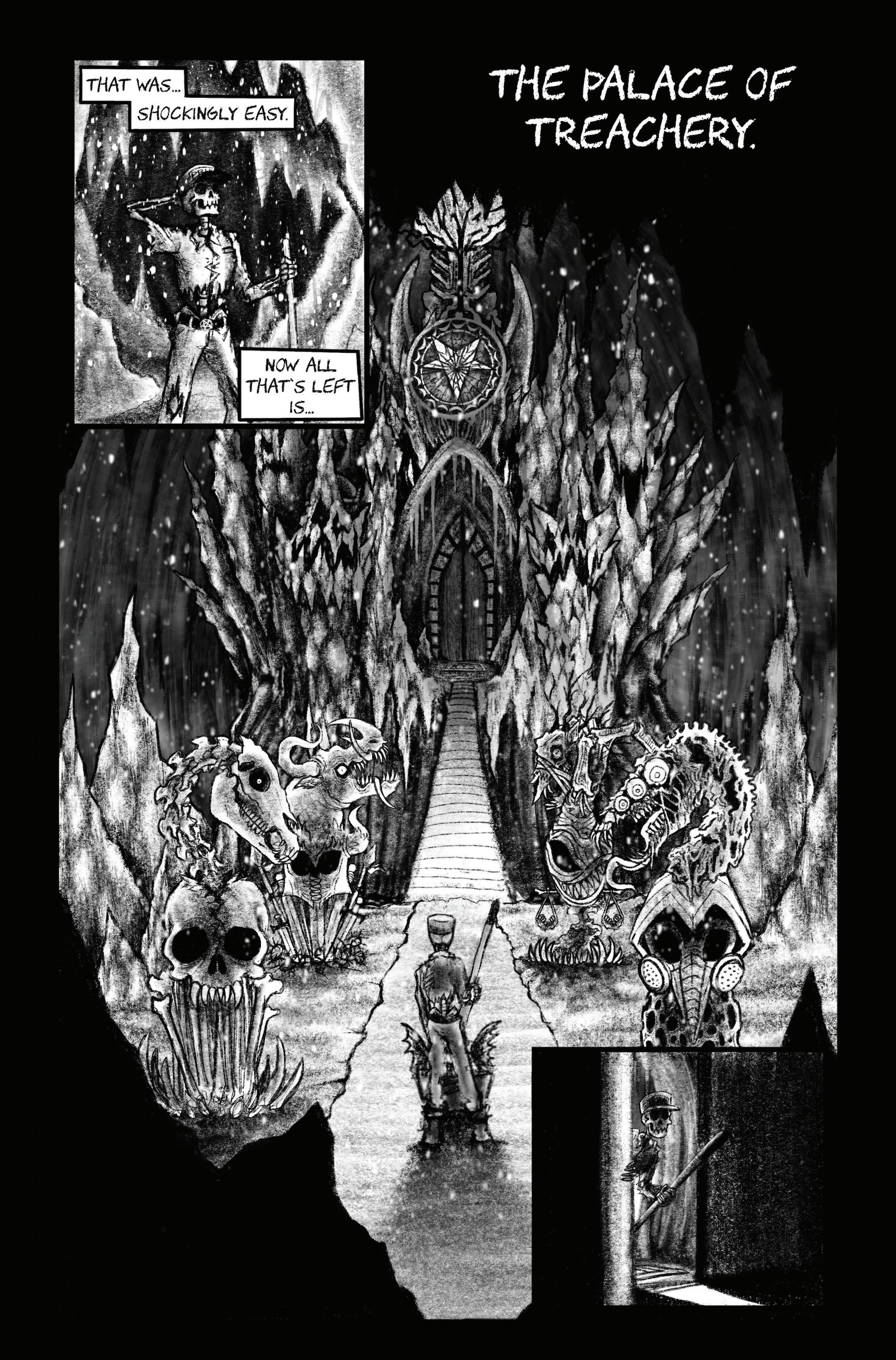

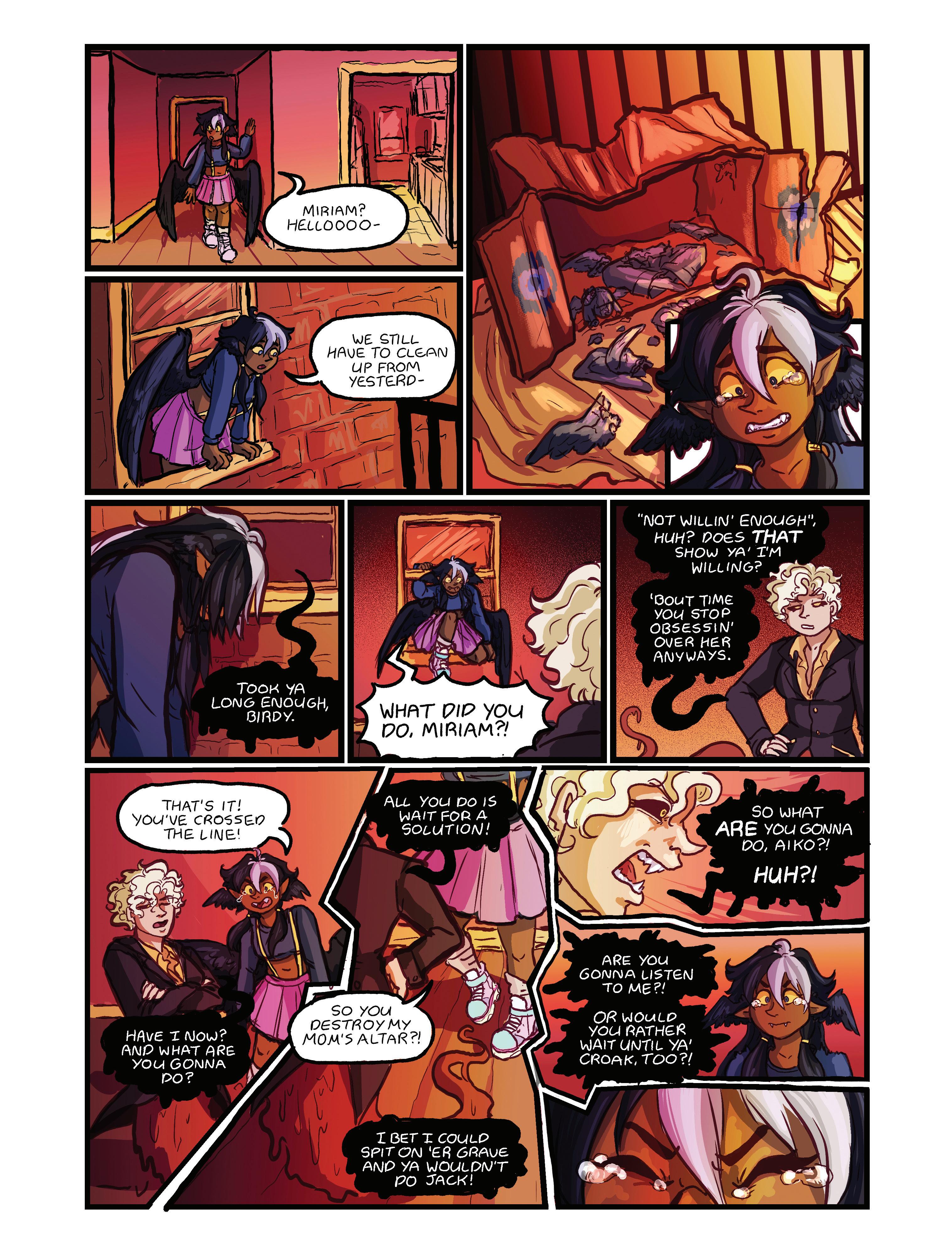

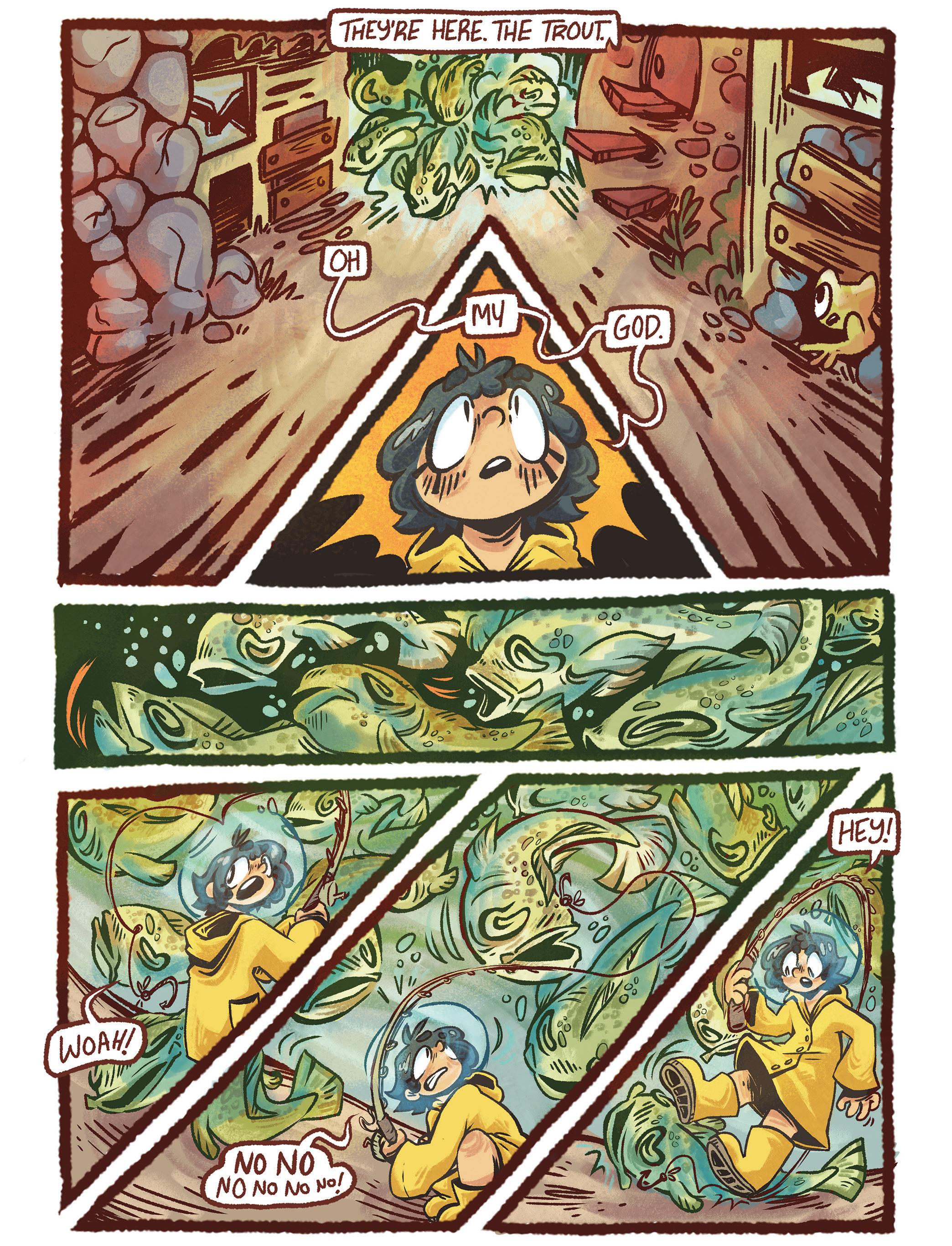

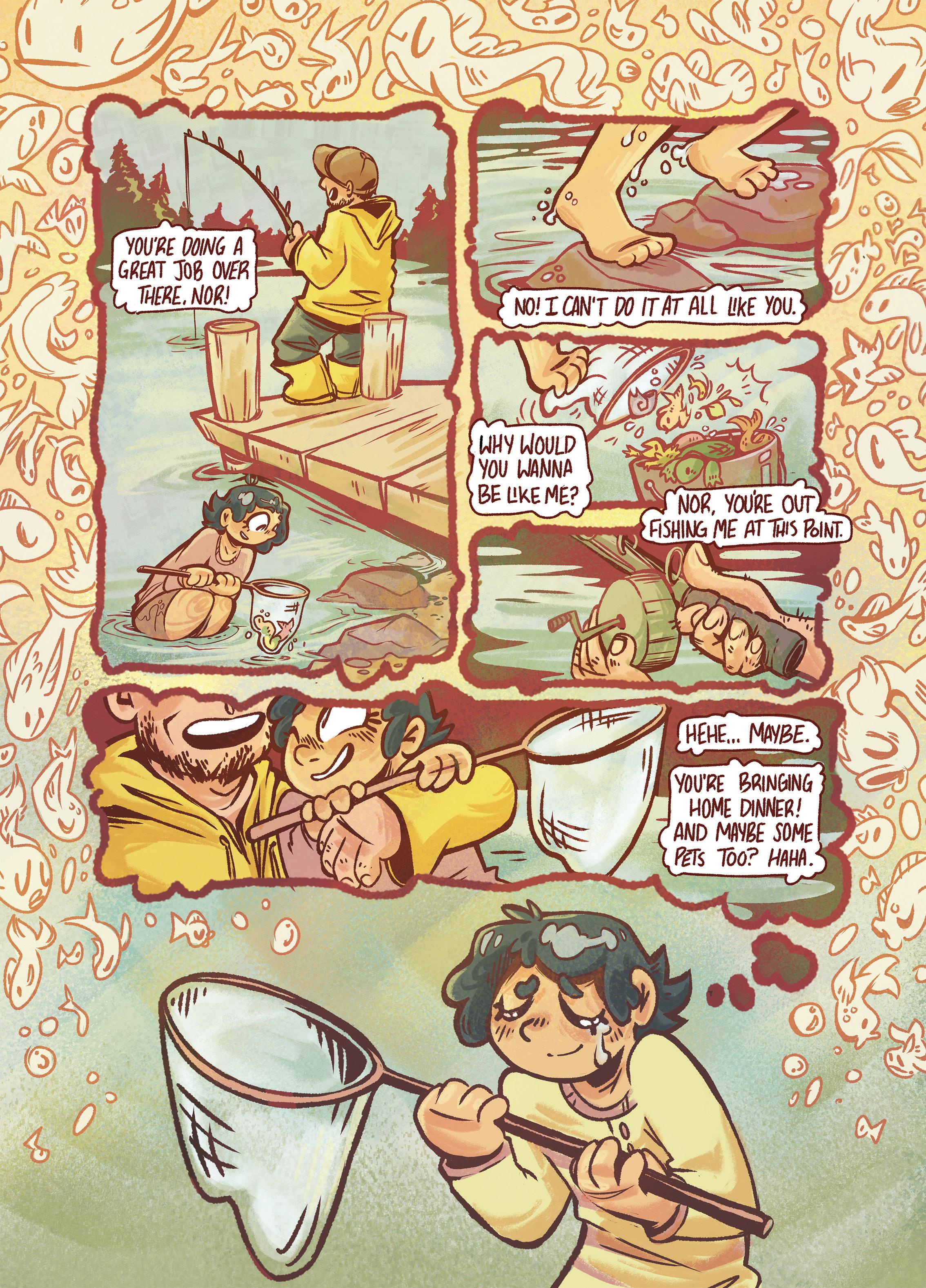

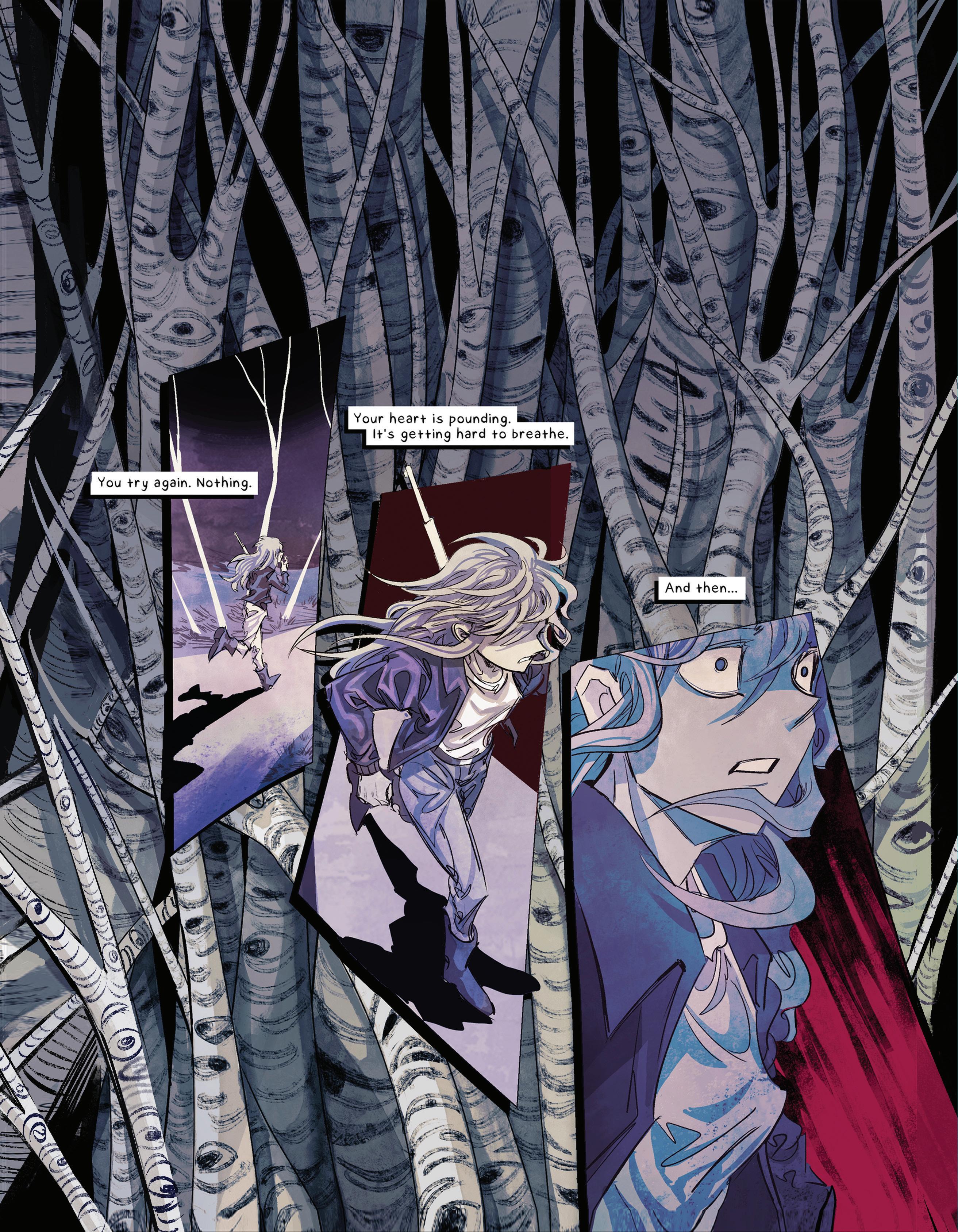

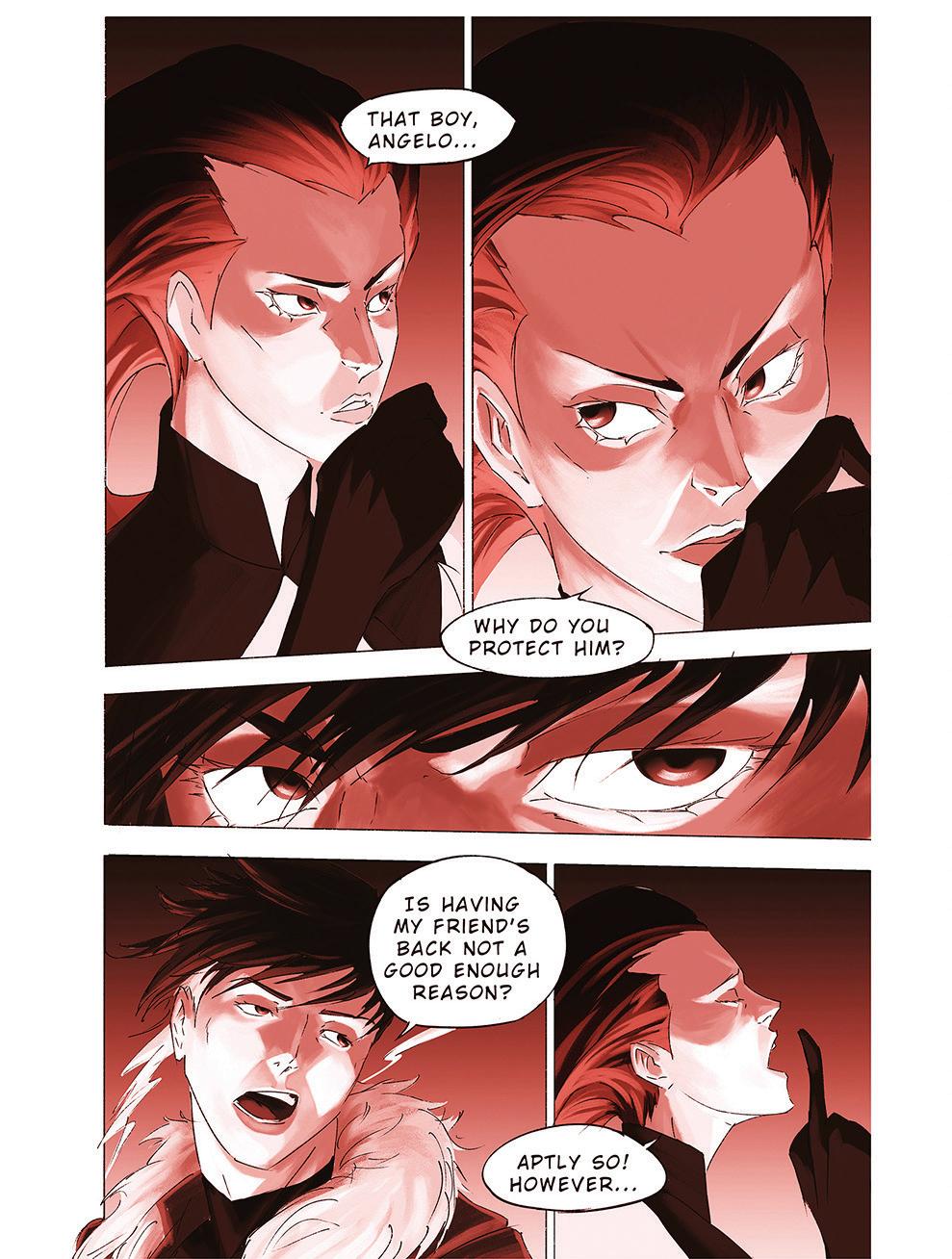

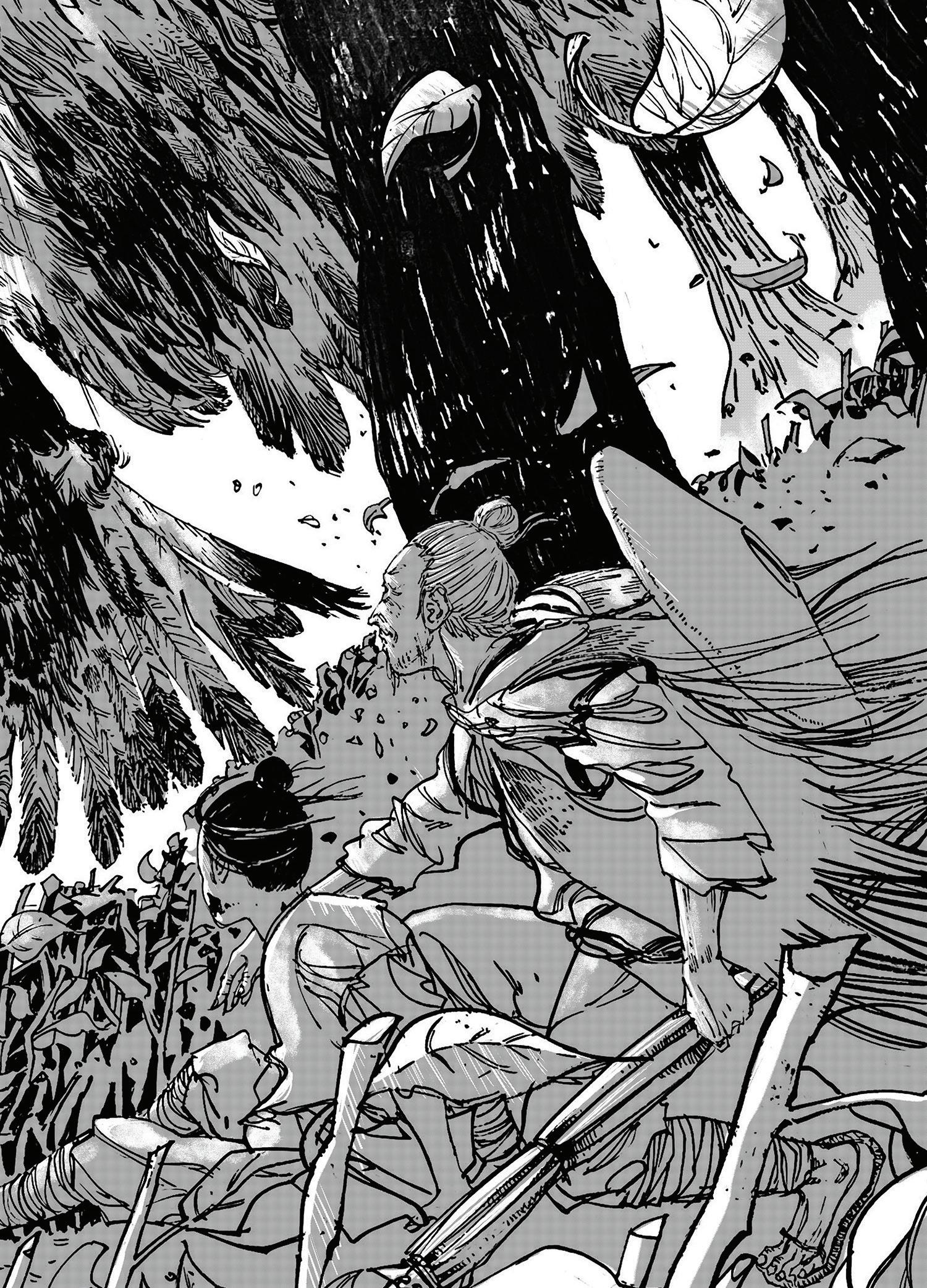

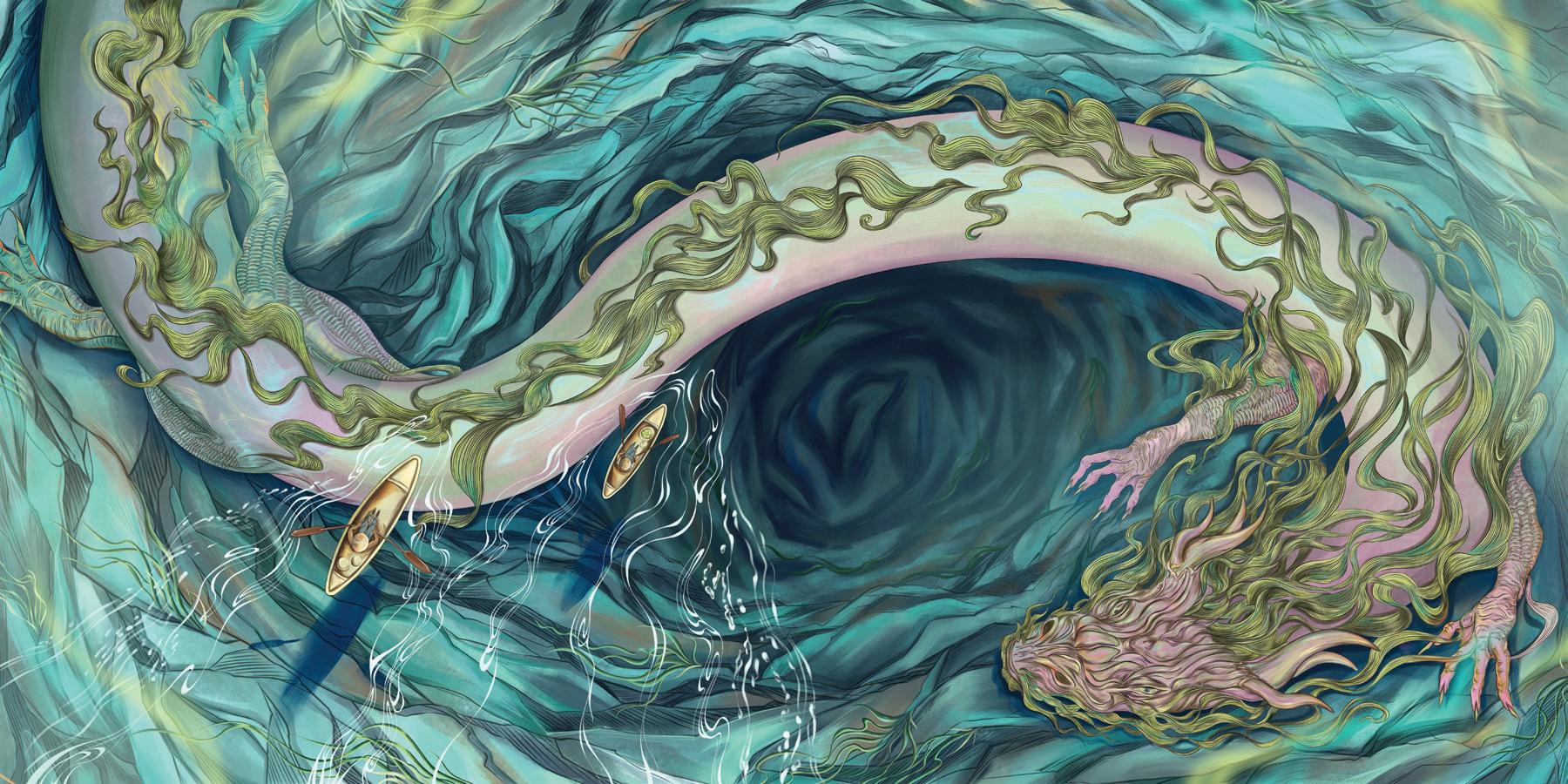

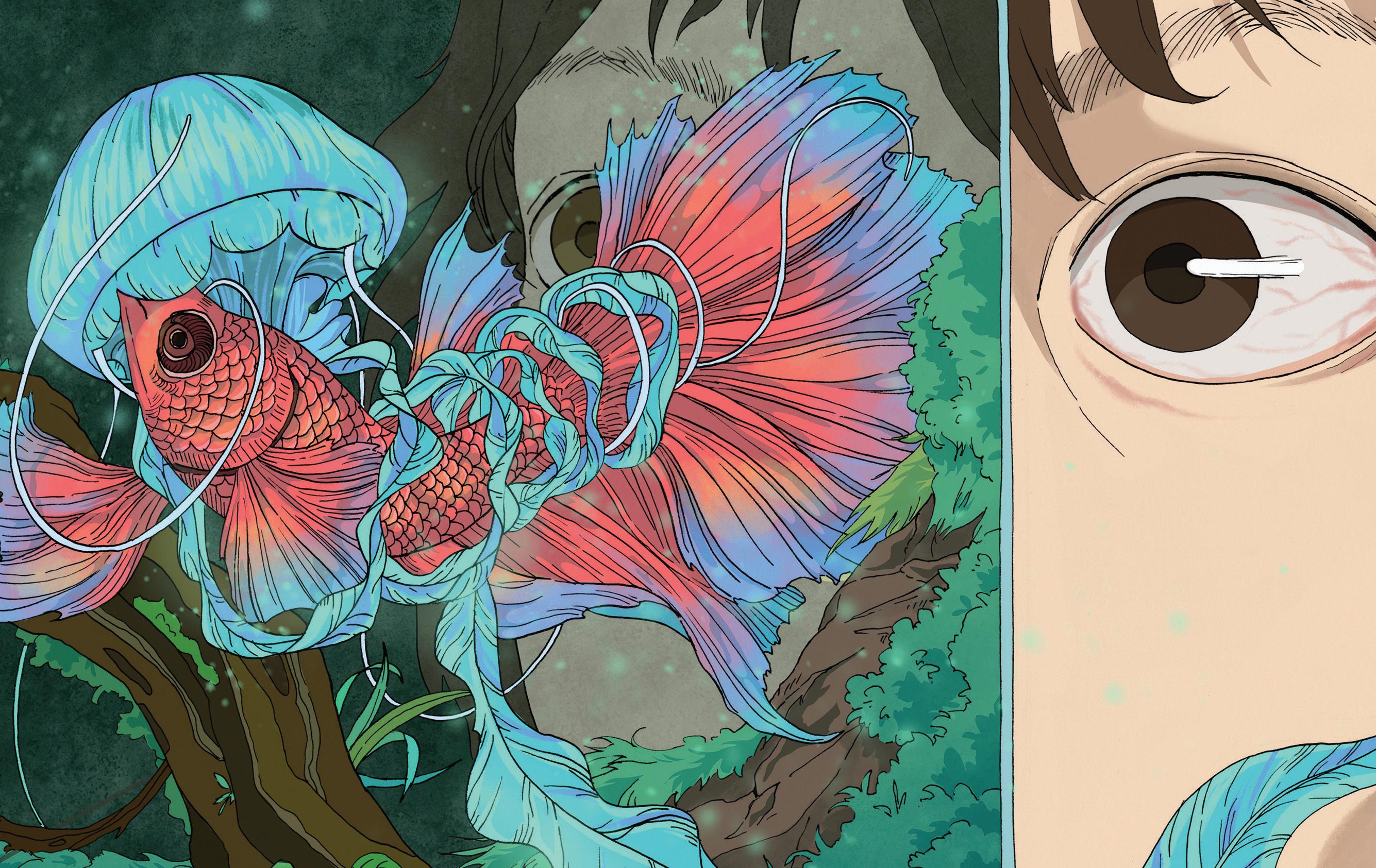

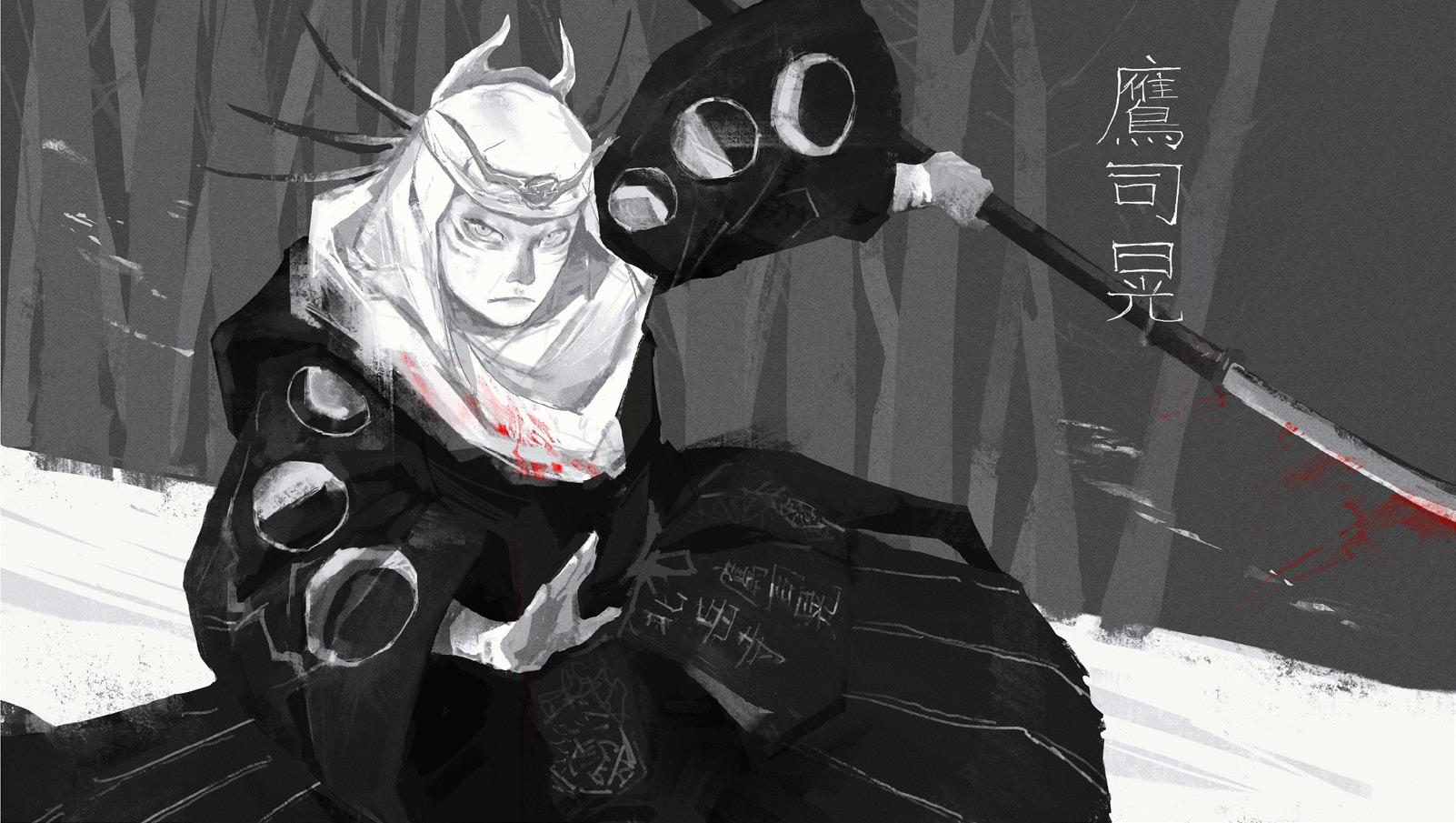

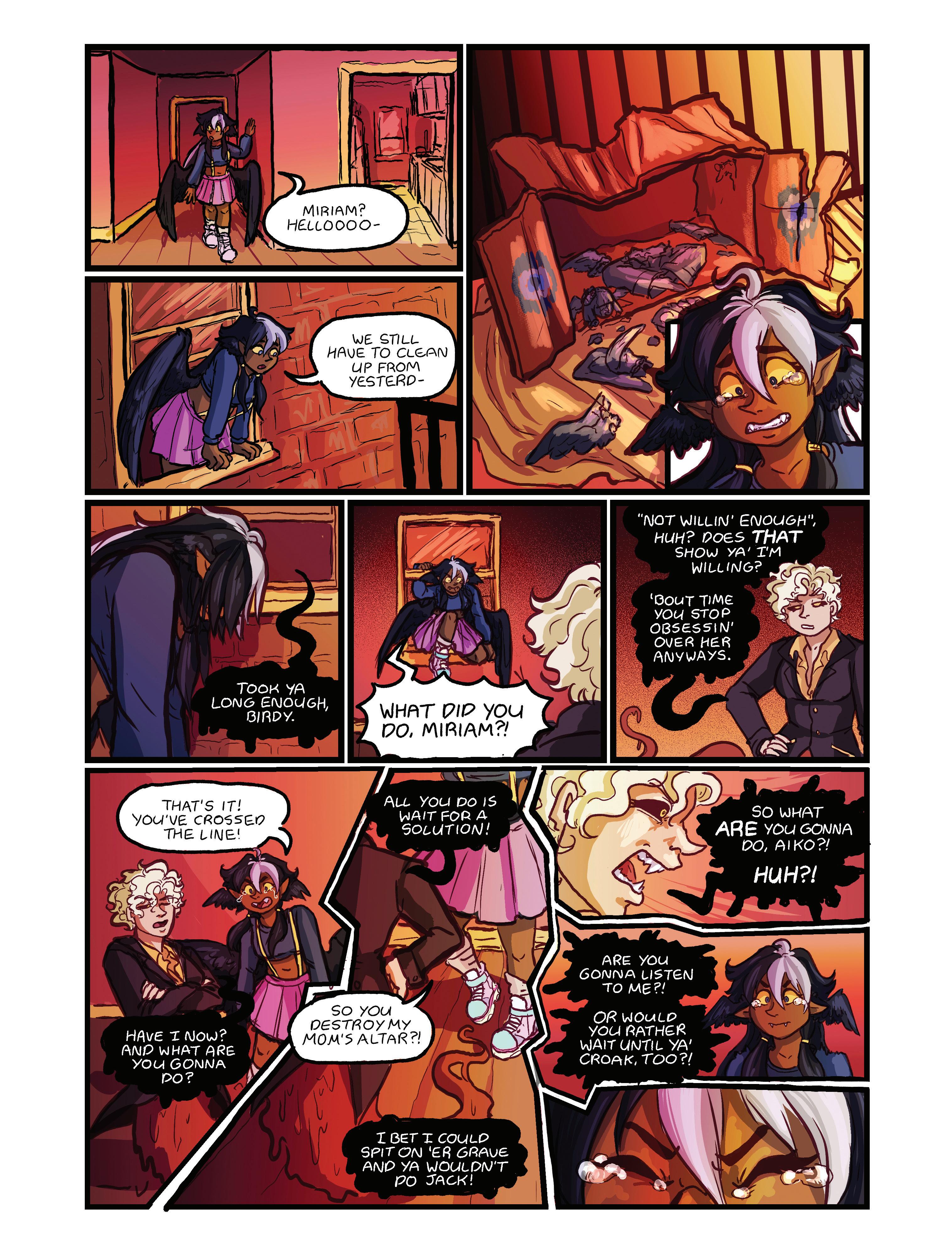

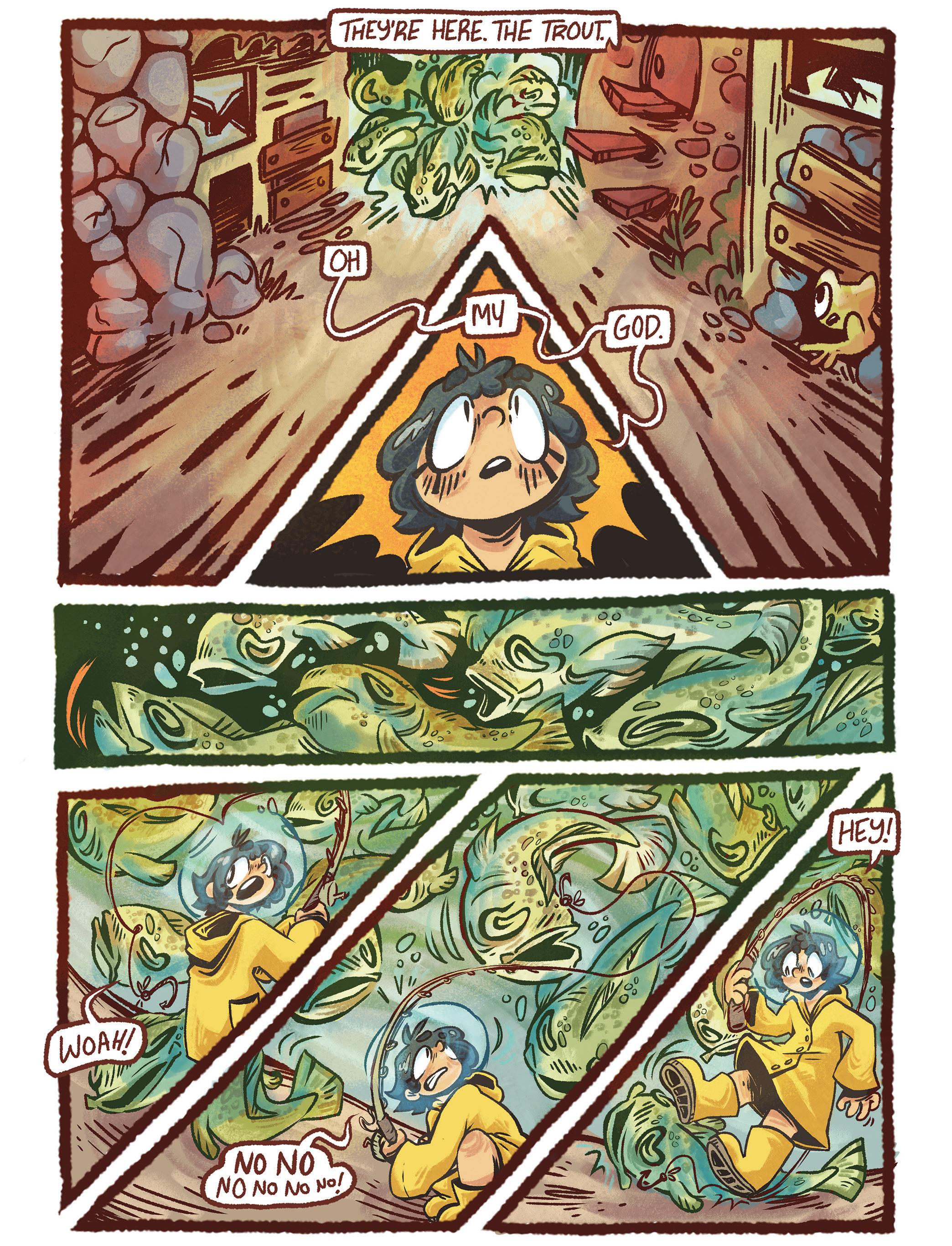

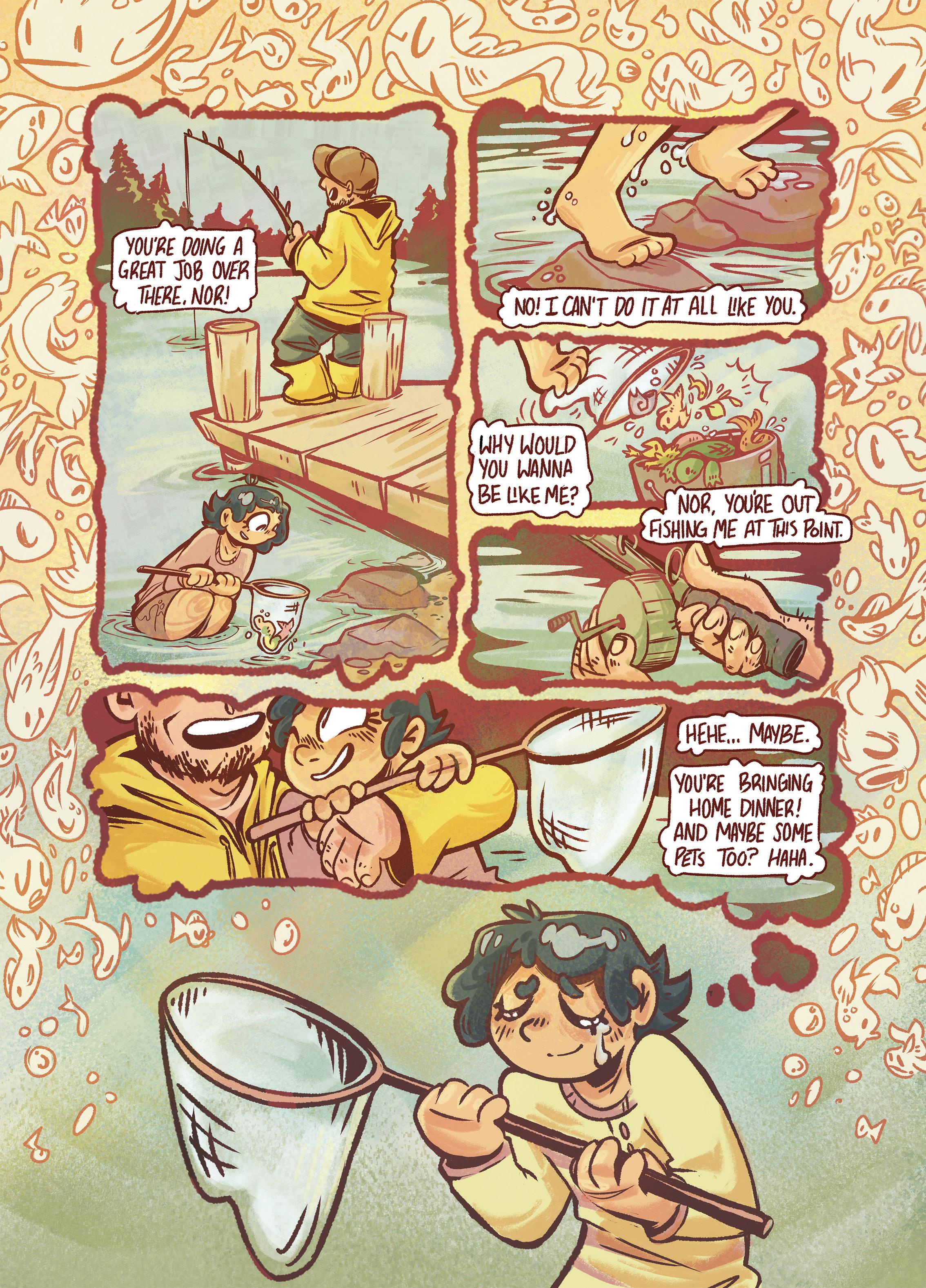

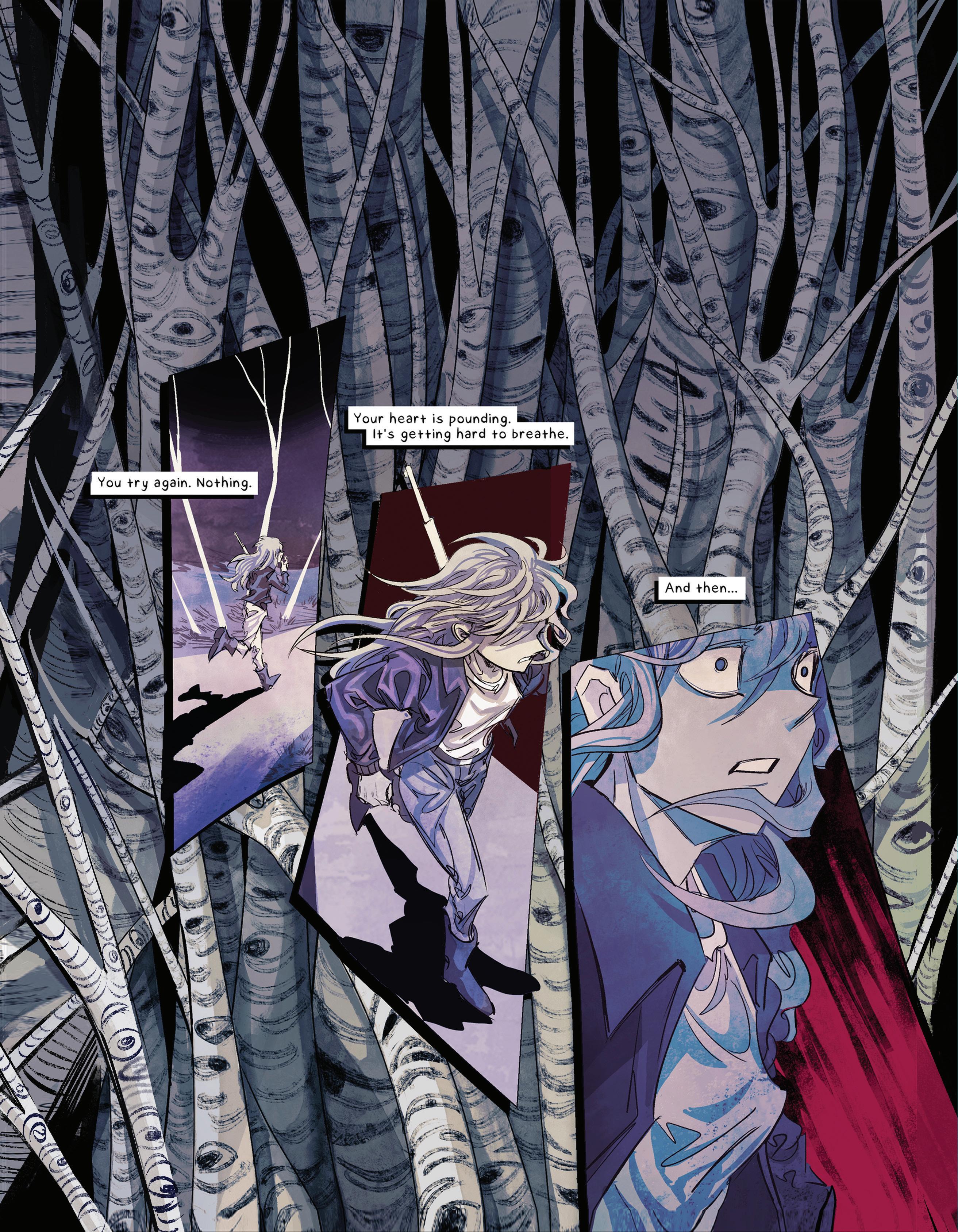

Cal Botelho 18 Freddie Della Famina 20 Natalie Riolfi 22 Kaitlyn Quach 24 Michael Barletta 26 Sinclair Dowty 28 Nahia Mouhica 30 Madelyn Sackett 32 Yeabin Lee 34 Marko Palushi 36 Xiomara Pardo Reyes 38 Zhiyu Lin 40 Allison Doll 43 Koby Clarke 44 Gloria Lee 45 Sabrina Reyes 46 Apollo Baltazar 47 Ian Van Doren 48 Ariel Lachance 49 Spark Park 50 Yoo Jin Ko 51 Sarah Langston 52 Jaz Mason 53 Aiden Franco 54 Cat Kaiser 55 BFA Comics Senior Thesis Faculty JOSHUA BAYER NICHOLAS BERTOZZI DAVID ROMAN Cover: Nahia Mouhica @PEACHIARE NAMOUHICA.WIXSITE.COM/ NAHIAMOUHICA

See you at school,

SENIORS

A CONVERSATION WITH

ANate Powell & Keith Mayerson

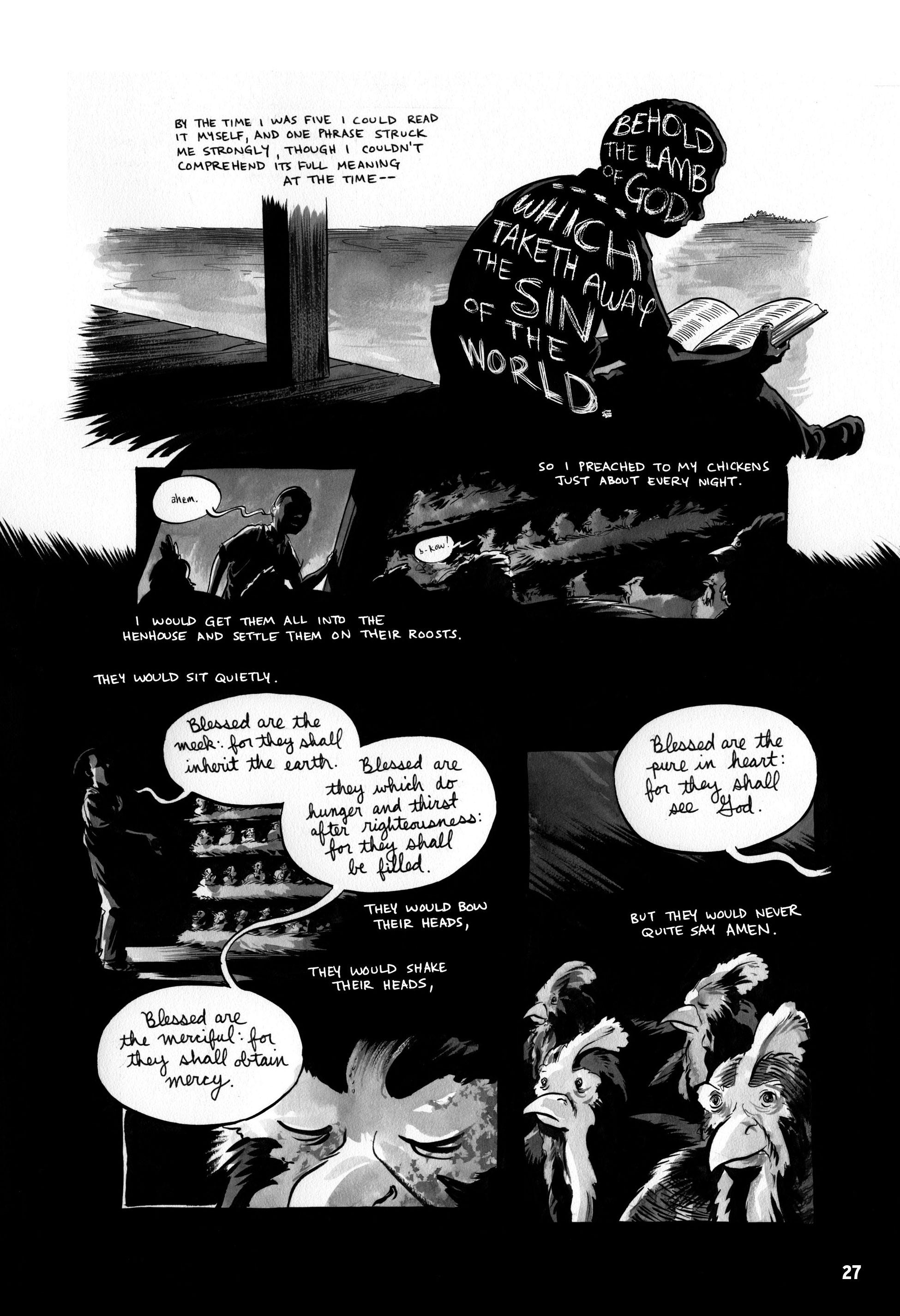

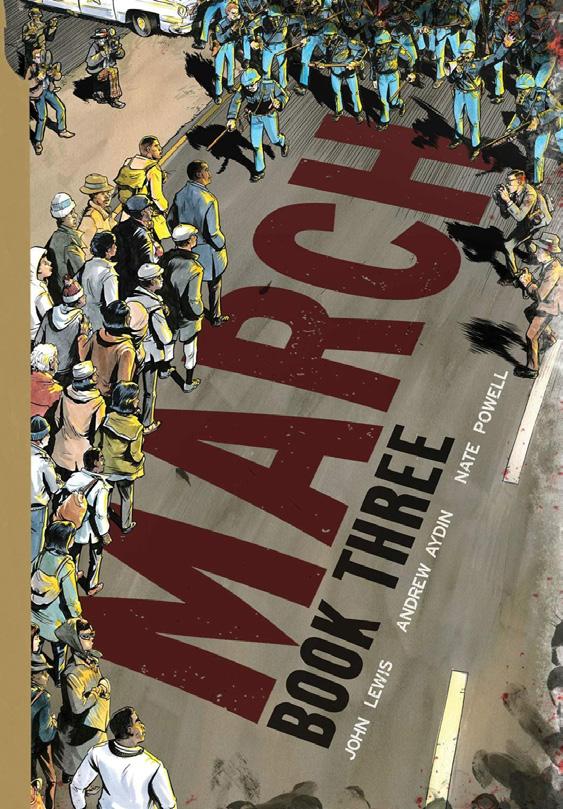

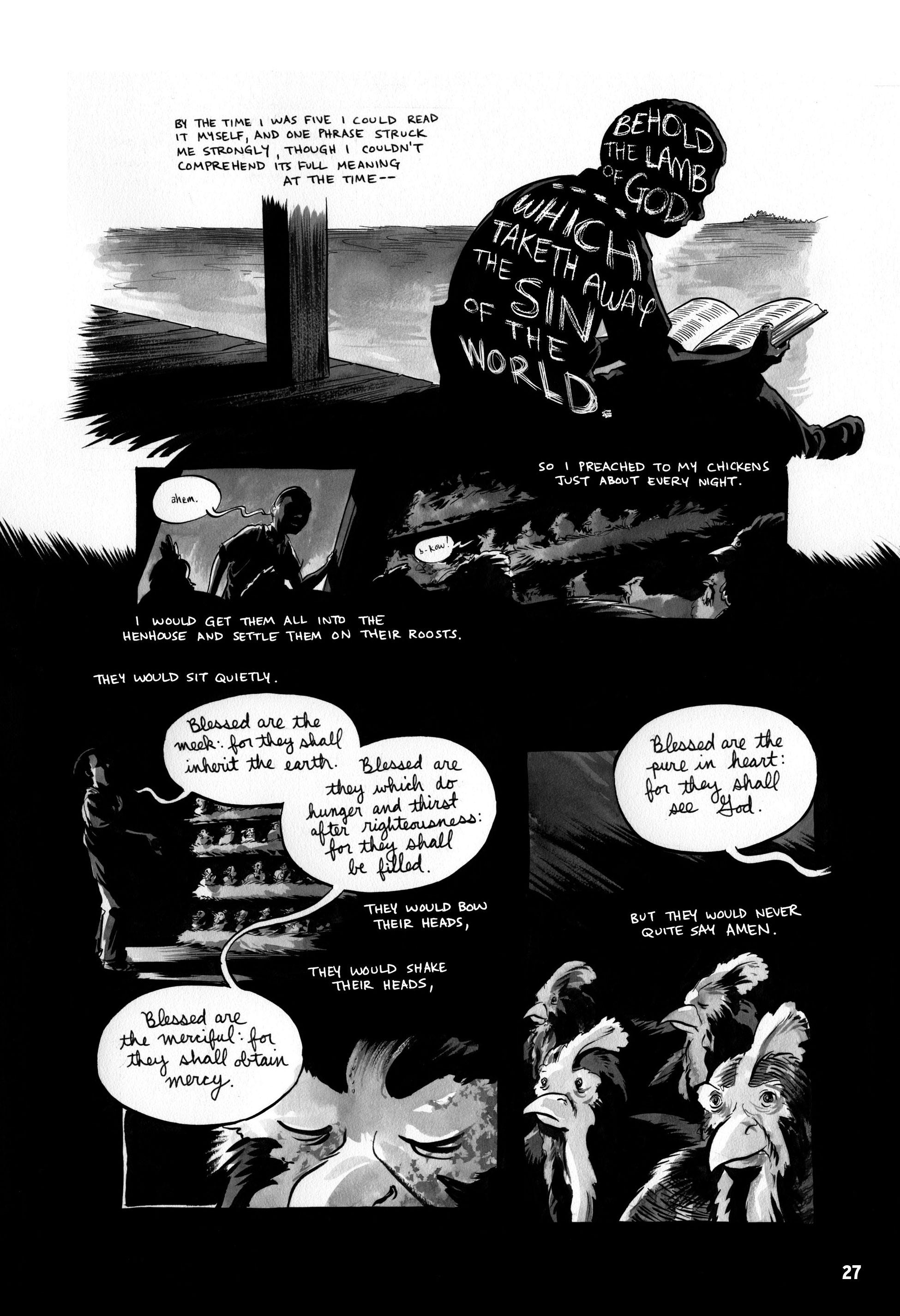

fter graduating from SVA in 2000, Nate Powell began a prolific career writing and drawing comics, winning two Ignatz Awards for his debut graphic novel, Swallow Me Whole. He is best known for drawing the acclaimed March trilogy in collaboration with Congressman John Lewis, which has won a number of prestigious prizes including the National Book Award.

Keith Mayerson, Nate’s former SVA teacher, recorded a conversation with Nate for COMX magazine. Keith is the author of Horror Hospital Unplugged, and the recently published “wordless novel” My American Dream. Keith taught Cartooning at SVA from 1994 to 2016, was Cartooning coordinator from 2005 to 2016, and is now professor of art at the University of Southern California (USC), where he began a Visual Narrative Art program and minor.

KEITH: Nate, it’s great to see you! Remind me, where were you living when you were in high school, and when did you graduate? And how did you end up at SVA?

NATE: That was ‘96. I’m from Little Rock, Arkansas. In my senior year of high school, I had an existential crisis where I listened too much to the prevailing wisdom of my parents’ generation, and, despite the fact that my lifelong passion was comics, I hadn’t really thought about anything that I was going to do to continue to hone those skills. I wound up signing up to go to George Washington University in D.C., which, thankfully, had a pretty good drawing program. But the existential crisis hit, and I was like, “I know what I have to do!”

I broke it down to my parents. I immediately transferred to SVA for my second year of college. So I had you in ’98 to ‘99. It seems unreal that I only had you for one school year, because your class was the vortex around which so much of my other classwork revolved.

KEITH: Wow, thank you! Probably you were in sophomore Principles of Cartooning.

NATE: Right. Since I got all my humanities classes pretty much done in my freshman year of college, I had, like, 18 studio credits every semester junior and senior years and was just extremely focused on integrating any class work and lessons into the comics that I was already doing on my own time.

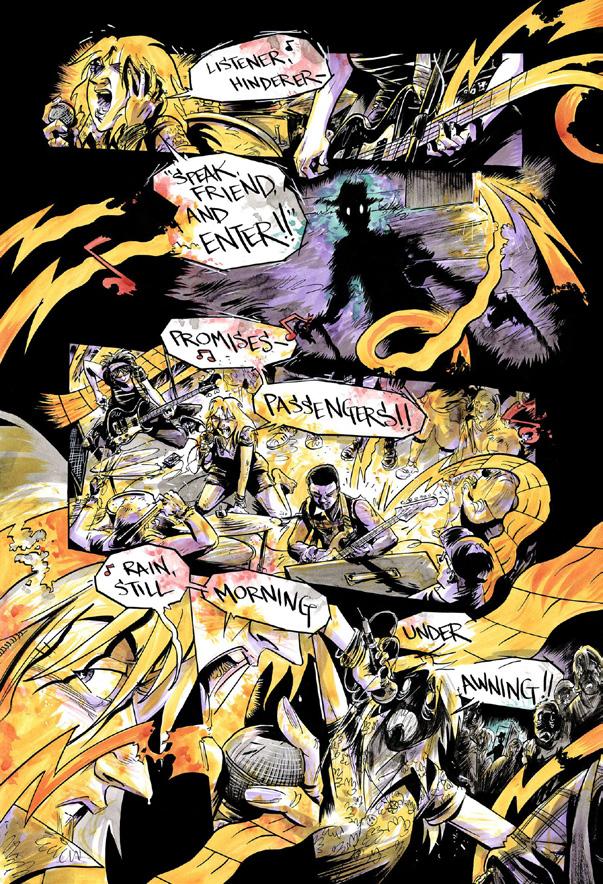

because my entire life was wrapped up in extremely do-it-yourself pursuits, mostly with my band. A lot of my work was structured around what was filling my time, through music and the punk community.

All of my work in comics revolved around the fact that I scheduled my life around being in a punk band—always touring, playing shows or recording. I was rather prolific at the time with comics, but I never did a story longer than 50 pages because of that.

KEITH: How did you know about SVA, back in that era?

NATE: Comics were running really deep throughout my band, and two of my best friends had already started art school. I heard about SVA through Mike Lierly, who was in your class as well. I kept getting word about teachers, classes, projects and stuff that was going on at SVA. It was kind of a no-brainer. Mike and I immediately combined forces and decided we were going to move to New York City together to continue the path that comics had opened up for us.

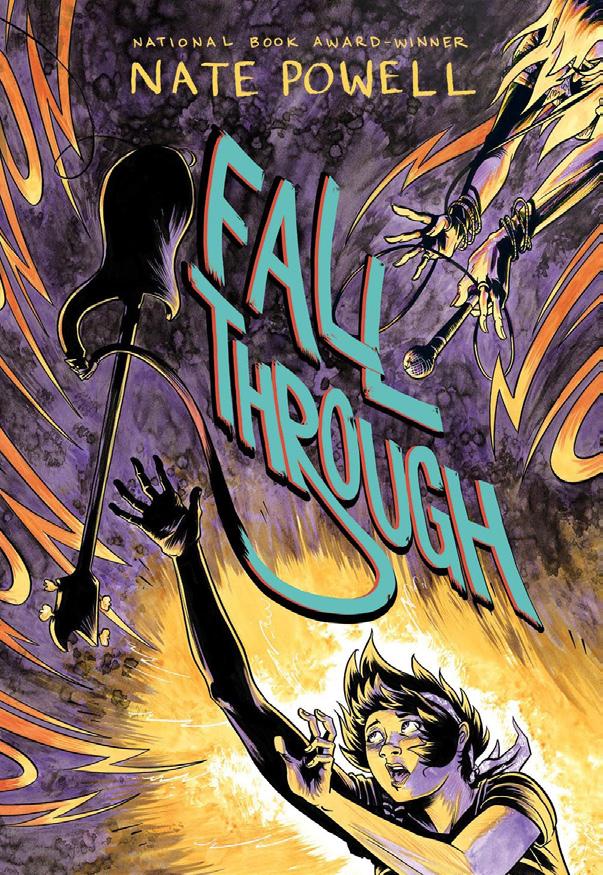

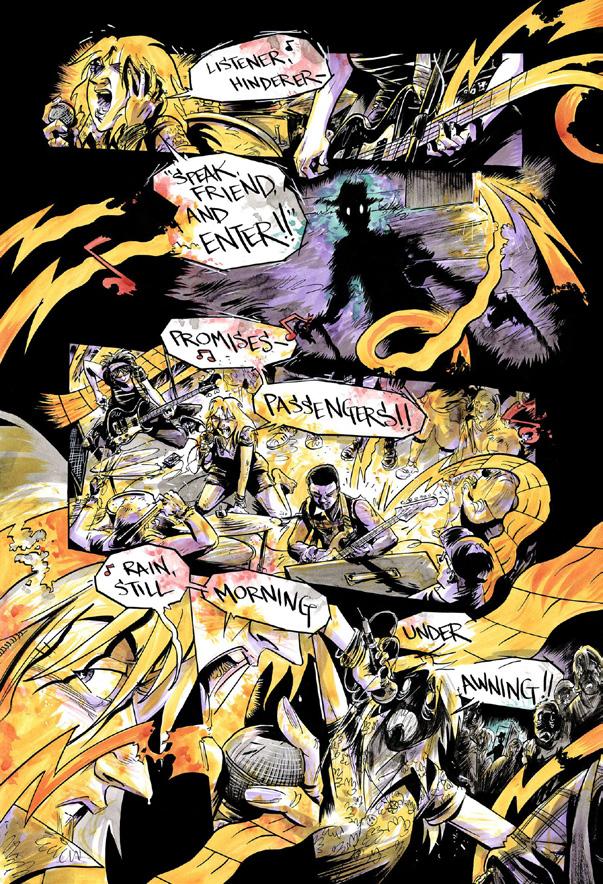

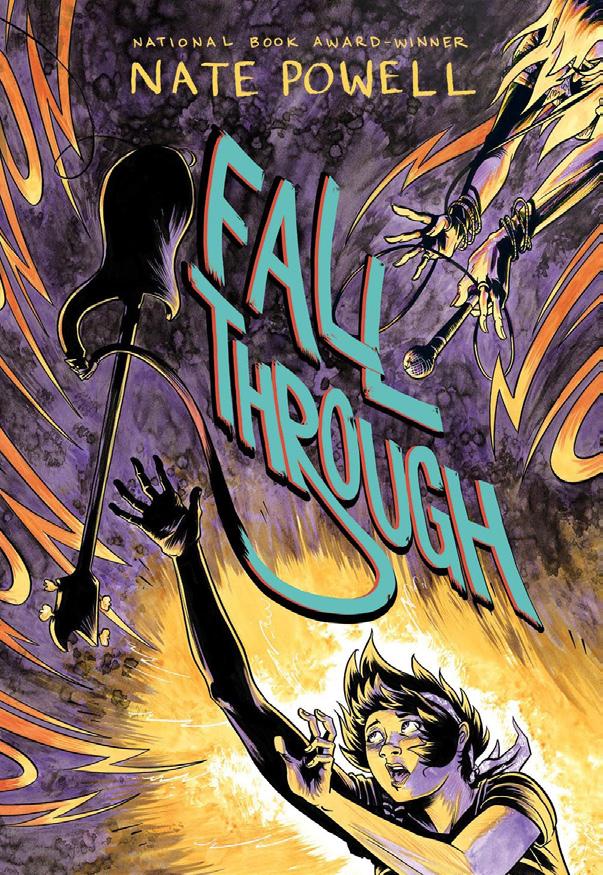

KEITH: Being in a band was really important for you then, and I know you’re about to publish a book, Fall Through about your punk rock years, told through different personas, coming out around the same time that this interview is going to be in print. You would tour with your punk band and sell your issues of Walkie Talkie to promote your work. Comics are like punk rock in that they’re really about speaking to your community, to help people relate to one another through the “music” of your drawing and writing.

NATE: Punk, in essence, is a folk art. The people who consume and view and engage with the art are typically also the people making the art. It works great in terms of people finding and magnifying their voices. At that time, I had given up on being able to make a full-time living out of drawing comics. One reason was

I stopped being in my main band. All of a sudden, I had as much time as I needed to make a story, whether it was 50 pages or 500 pages. It was such a major shift in how I organized my time and what I expected of the work I made in comics.

I moved to Kansas City for a bit, then started hop, skip and jumping across America, living in Michigan, Massachusetts and Rhode Island, before settling here in Bloomington, Indiana.

KEITH: All inexpensive places to live, which is healthy for a cartoonist, especially when you’re starting out. Comics are not provincial, like in the fine art world, where you need to be in New York, or L.A., or a place where there’s a marketplace. With comics you can live anywhere, as long as you go to conventions and let people know that you’re alive. When you were touring, you were also distributing your comics, right?

NATE: Yes, my band’s first tour in ‘97 was my first experience actually making my books accessible to people who did not live in my home state of Arkansas. It was still very much a do-it-yourself operation, in that I was physically handing copies of my comics to people at gigs in basements or living rooms. It expanded from there.

KEITH: How did you end up settling in Bloomington?

NATE: One big reason is, during those very intensive years of touring, we became deeply embedded in the worldwide hardcore punk underground. Bloomington remains a really strong punk hub.

I knew that it was a cheap, friendly, supportive place. It’s a college town in a very conservative, mostly rural state, so it had an oasis-like quality to it. So alongside making comics and doing all this stuff, for 10 years before I started doing comics full time, I was doing direct care and advocacy work for adults with developmental disabilities. I thought it was important to begin to grow some roots here, as a professional caregiver. And then I fell in love and got married. And all that sort of snowballed at the same time that I had an opportunity to take a chance on quitting my day job and doing comics full time. So it all happened really fast.

KEITH: Our class was a particularly great class, right? I was thinking of the other band that had a great cartoonist in it, My Chemical Romance.

NATE: Gerard [Way] started at SVA the year after I was done there. We had a lot of crossover through friends and classmates from the in-between years, like Becky Cloonan.

KEITH: Wasn’t Farel Dalrymple in that class?

NATE : Farel was, and Brendan Burford, and Carlo Quispe, a fantastic cartoonist. And letterer extraordinaire Cory Petit! I’ve kinda fallen back in love with the X-Men. I’ve re-read thousands of pages of X-Men. All of these books are lettered by my old friend and classmate, Cory, and he’s an incredible letterer. Lettering is the glue that holds comics together on a formal level. I think my Eisner nomination for best letterer is the one that is the highest honor for me. I’ll read X-Men and really focus on Cory’s lettering and what he’s doing, page by page, and it’s been

very helpful for me as a cartoonist.

KEITH: Superhero comics are the Wall Street of the comics world. We need superhero comics to do well. They keep the comic book stores open. SVA has an older history, where comics had become sort of misbegotten within the administration. I’m so glad that you guys were the first generation rebooting it. I started teaching there around that same time in ‘96. We sort of revolutionized the comics program to where it is today, that they could say it’s the Harvard of comics colleges. Not that there are many comics colleges to compete with, but it’s really a great program. My job teaching there, growing into being Cartooning coordinator, and Tom Woodruff taking over the program and really focusing on comics and making it a much better program, led us to where we are now. Then in 2000, there was a sea change where all of a sudden, half my classes, wonderfully, were women.

NATE: It was a revolutionary shift. Then if you skip ahead even just five years, the impact that Raina Telgemeier made, transformed that sea change into a new generation of creators. It’s amazing now to be 18 years past that point and realize that Raina’s readers are adult creators now!

KEITH: There was a group at SVA called Estrigious. It was Becky Cloonan and her friends. They had their own website— before people really had websites—that would get like a thousand hits a day. They would do compilation comics and go to comics fairs together and support one another.

The male equivalent of that was Meathaus. Were you a part of Meathaus?

NATE: Yes, I was back in Arkansas and started corresponding with several of the Meathaus folks. I contributed to two of the issues between 2001 and 2002. I consider the Meathaus crew to be my

peer crop of cartoonists from that sliver of time. Farel was in it and James Jean, Becky Cloonan, Esao Andrews, and Tomer and Asaf Hanuka. And Dash Shaw and Tom Herpich. It had a really solid lineup.

KEITH: There is strength in numbers. All great art movements happen with like-minded people, oftentimes who went to the same art school. The surrealists all left a school that they didn’t like, together. R. Crumb and the underground cartoonists got together. The women of that generation, with Twisted Sisters and Diane Noomin—who also was a wonderful teacher at SVA—did their own anthologies.

With your class, I still remember the real feeling of … a commune of cartoonists and how you guys were so dedicated each week to bringing in work and putting it on the wall. Was Steve Uy in that class?

NATE: Yes! He brought the thunder more than any other student. You were like, “Okay, you guys, we’ve got this 16-page story you’ve got to turn in. What do you have, Steven?” And he’d be like, “Well, I completed this 80-page book. It’s fully inked and lettered. I’ve already printed it. Would you like a copy?”

KEITH: Yeah, Steve got hired right away! He was at the bar near SVA after graduation, and he had his portfolio with him, and he was with a friend who was there with a Marvel editor, and the friend said, “Marvel editor! You should check out Steve’s work!” The Marvel editor looked through dozens of pages in his portfolio, and was like, “Yeah, I’ll hire you right away.” It’s usually not like that!

NATE: Right on. Luck is a real thing. There is so much to be said for diligence and discipline and vision, but you always have to be ready for unexpected stuff to happen just whenever, and be open to it changing the course of your life.

KEITH: Molly Ostertag did a comic called

Strong Female Protagonist in their sophomore year at SVA. They continued it for three years, and then, with the Kickstarter campaign, they published it. And they got, like, 60 or 80 thousand dollars to publish their graphic novel, and I remember being at New York Comic Con with Cartoon Allies kids, and Molly was at the Top Shelf booth with their books. And I said, “Top Shelf! You’re distributing Molly’s book? They began this in my class!” And Top Shelf was like, “Yes, we’re so proud of it.” First Second was right across from Top Shelf’s booth, and I was like, “Oh my gosh, that’s my student, Molly Ostertag.” And they were like, “Oh, yes, we have them contracted with us for next year.”

NATE: Those Witch Boy books are beloved classics here in the house. The Witch Boy trilogy has influenced my more recent fiction; I’ve become more embracing of genre. It’s been very freeing. Those books are one of the best examples of genre.

KEITH: Witch Boy took ideas of genre and, within the genre, critiqued it … Why can’t boys be witches? It’s very gender-fluid, and it really helps the world. Witch Boy, I think, was picked up by Fox Animation. Molly’s partner, N.D. Stevenson, did art direction for She-Ra, which, I think, is kind of like Becky Cloonan doing Conan stories; feminist creators retelling these very masculine kinds of adventure narratives.

NATE: And N.D. Stevenson’s work on She-Ra stands the test of time, as it’s a full execution of classic themes and tropes, throughout hero narratives, and being able to do it in a loving way that also confronts the source material, it’s able to turn it on its head.

KEITH: Cartoonists make great storyboard artists. We mentioned Tom Herpich; he worked on Adventure Time and Steven Universe, along with Hilary Florido. Rebecca Sugar from Animation at SVA

was the head of Steven Universe

NATE: My kids are eight and 11 now and watching Steven Universe with them has been fantastic. It’s been great being able to recognize that this is a radical shift in the expectations of narrative and emotional weight and in what is expected when we’re talking about narrative conflict.

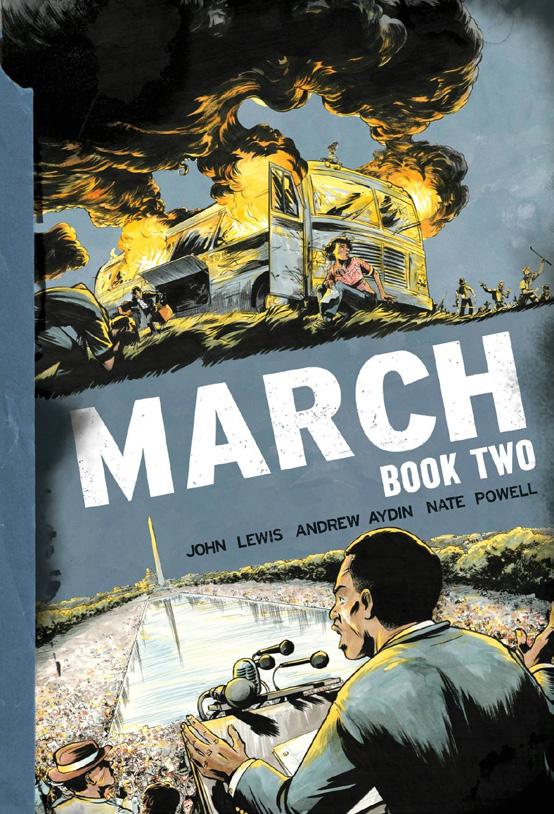

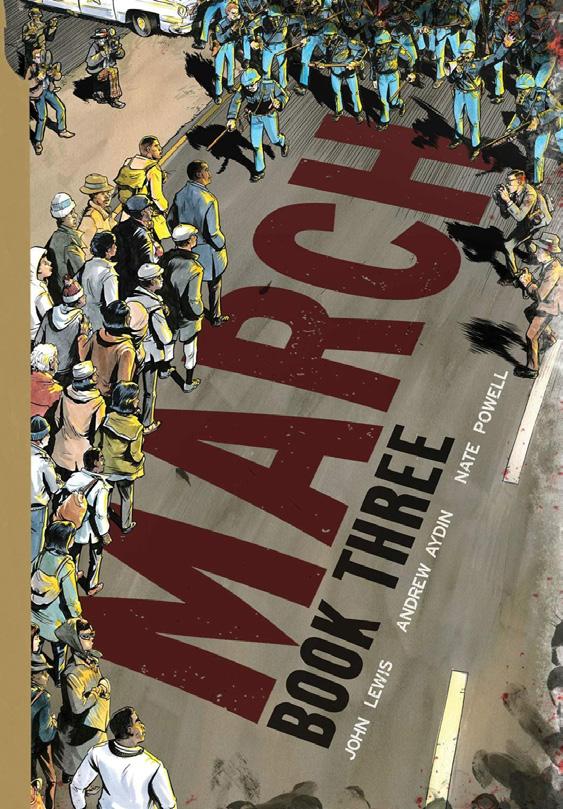

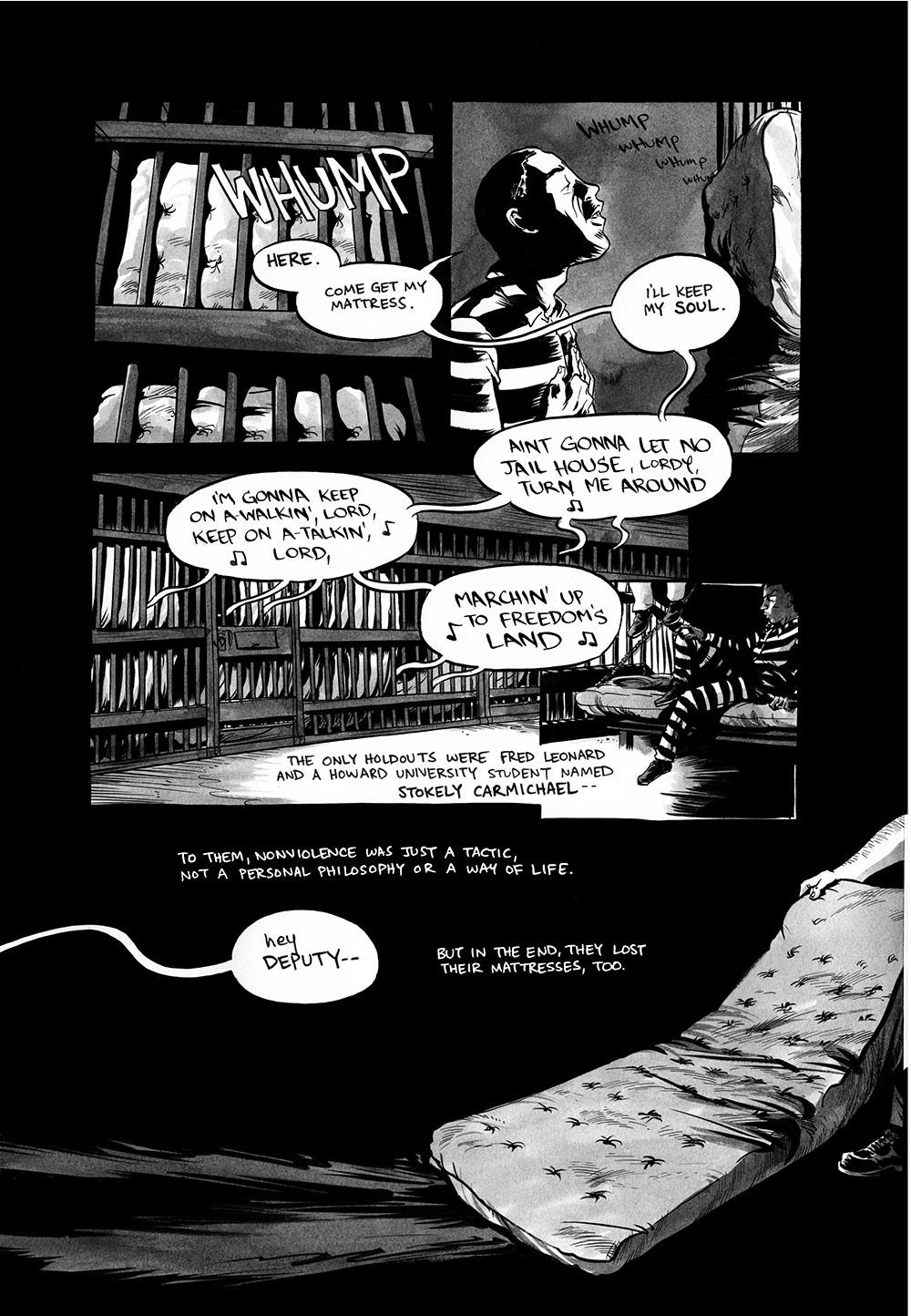

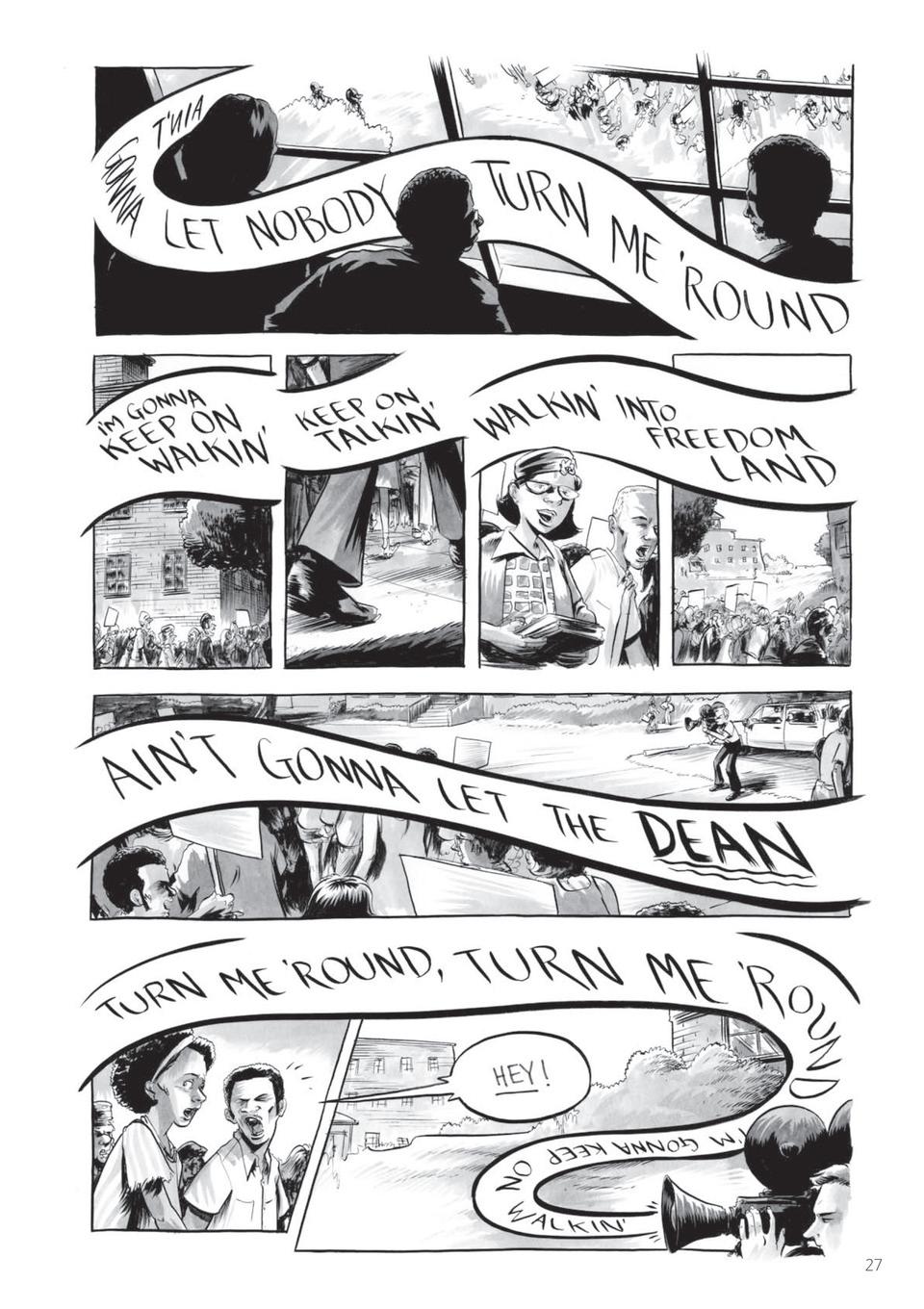

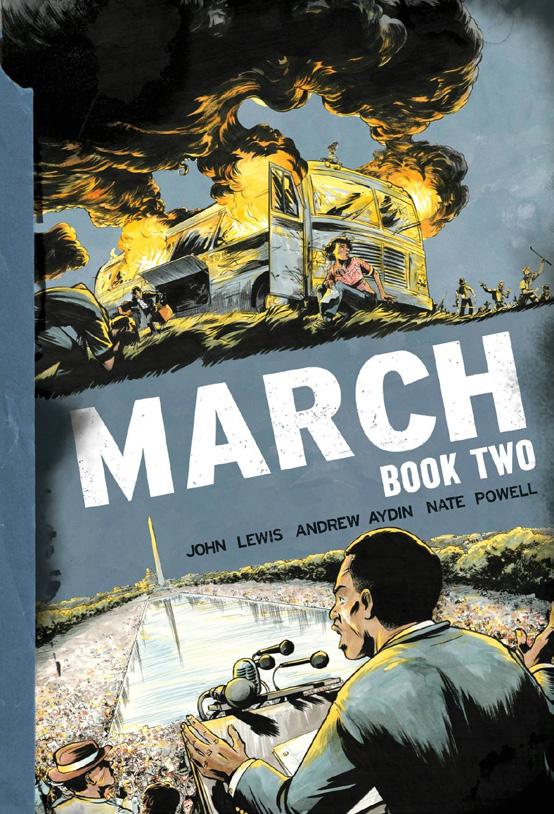

KEITH: Nate, what did you do between graduation and March? March in particular, for our politics right now, is so pertinent. With Congressman John Lewis, that collaboration, how did that begin?

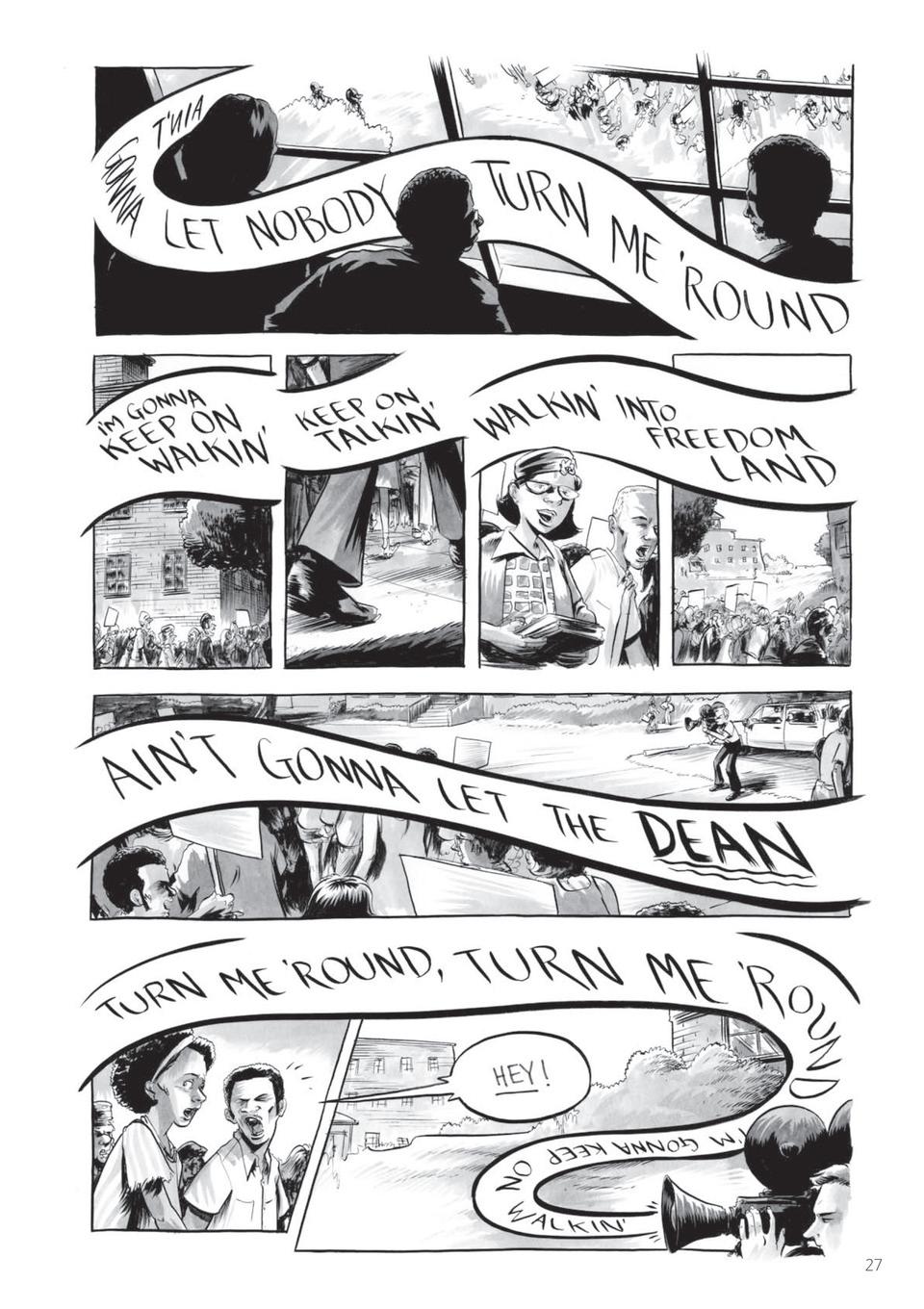

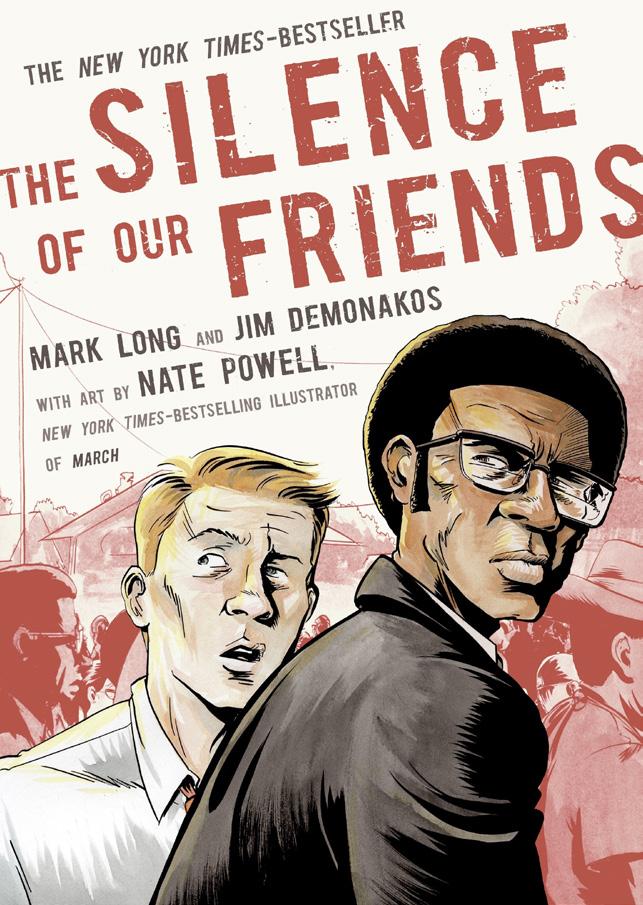

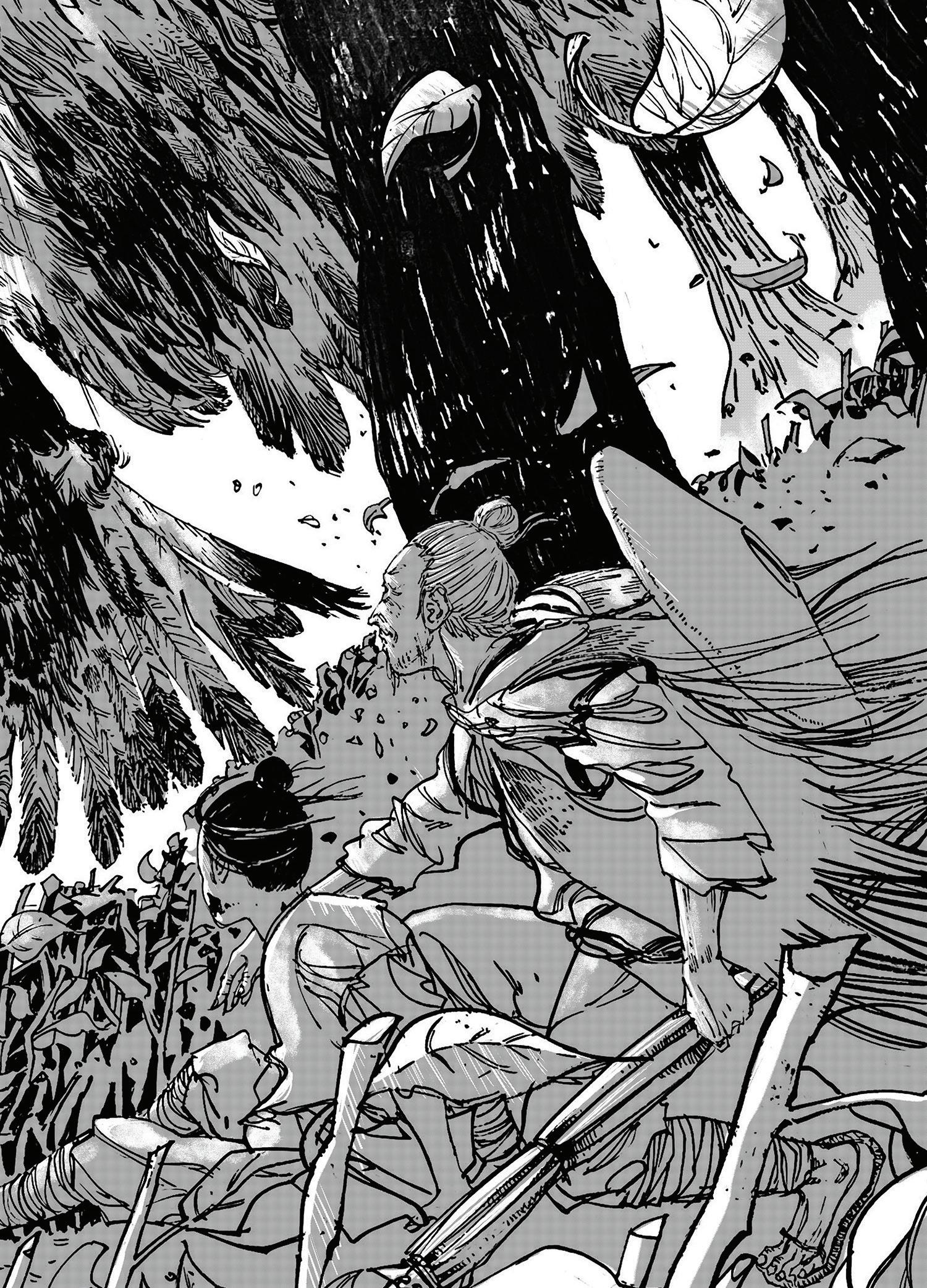

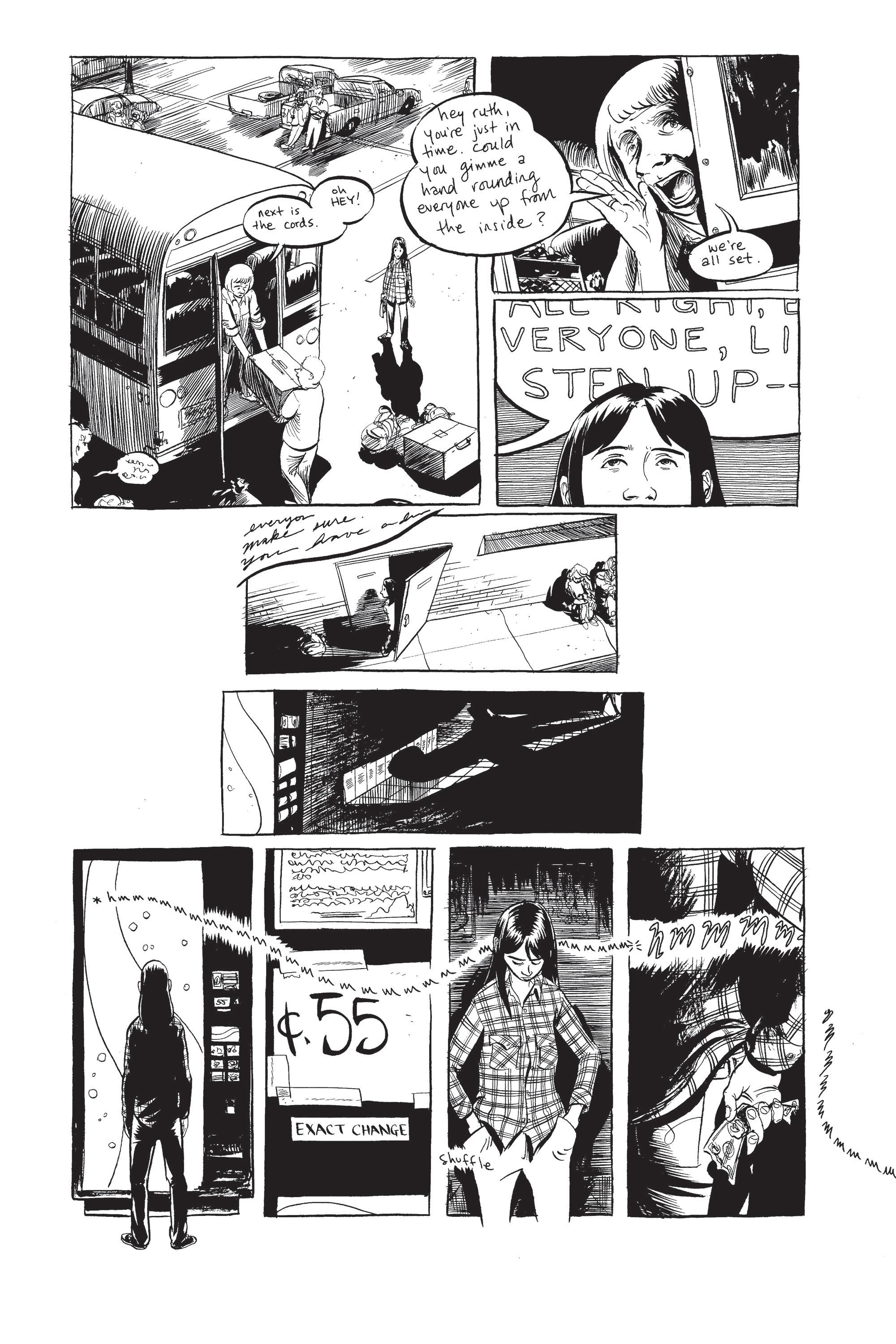

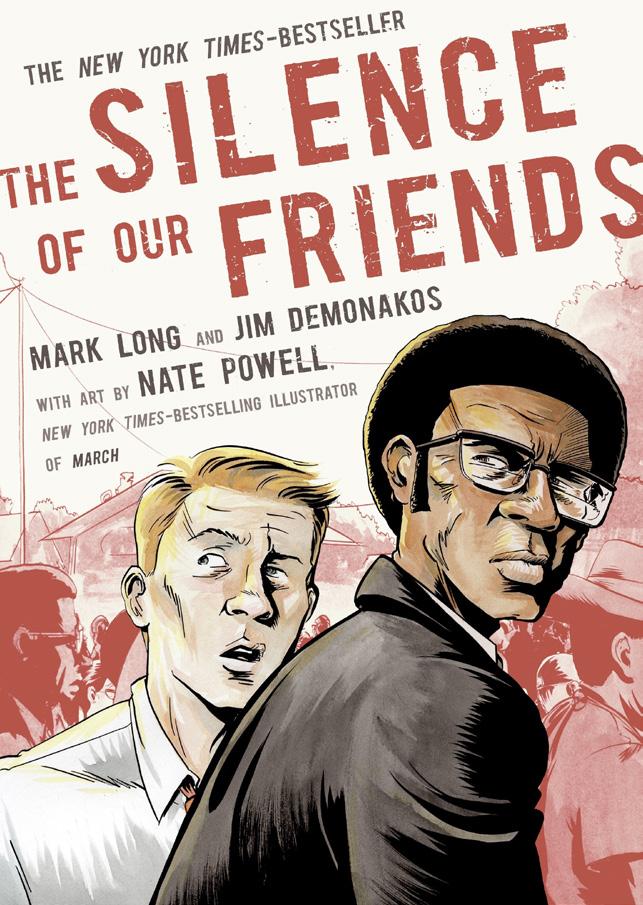

NATE: My first graphic novel came out in 2008, Swallow Me Whole. It took about six years total to make it happen. Once it was released I was surprised that people were actually reading it and were affected by it. What allowed me to quit my job to try being a full-time cartoonist was drawing a graphic novel for First Second called The Silence of Our Friends, which revolved around writer Mark Long’s life growing up outside of Houston in the sixties, set against the backdrop of a forgotten moment in the civil rights movement. I consider my work on The Silence of Our Friends as a boot camp for the March process, especially the reference and research, and issues of authorship, voice and privilege that went into working on March Andrew Aydin, the March co-writer, was a staffer for Congressman Lewis. They’d been working on the script for a couple of years. They cut a deal with Top Shelf to publish March, but with no artist. Chris Staros from Top Shelf called me up about a week later and suggested that I try out. One reason was because of my previous work blending fiction and nonfiction. I had done a little bit of it in short-form comics, journalism and nonfiction work for Brendan Burford’s Syncopated anthology.

KEITH: He was also the editor at King Features Syndicate.

NATE: Yes, and a real gem of a person. I did some demo pages from the script, and very quickly we realized that we clicked well together. I’m also a Southerner; as a kid, I lived in Montgomery, Alabama. My parents are from Mississippi. So it was very important that I had a lot of cultural and historical familiarity but also topographical familiarity, in terms of what kind of dirt, what kind of

roads, and what kinds of plant life. One reason why they wanted me to draw the March trilogy was because of my ability to balance this dreamy, intuitive, very personal kind of storytelling with a more objective, realistic, cartooning approach. So whenever I could, I was encouraged to lean on my own experiences and memories of living in the South in the eighties and nineties, especially watching these social and political shifts, which foreshadowed this dangerous return of very regressive outright fascism in the 2020s.

KEITH: My parents are also from the South, and I relate to that, too, in terms of my legacy. They got the hell out of there in the sixties, when they saw their friends become fascists.

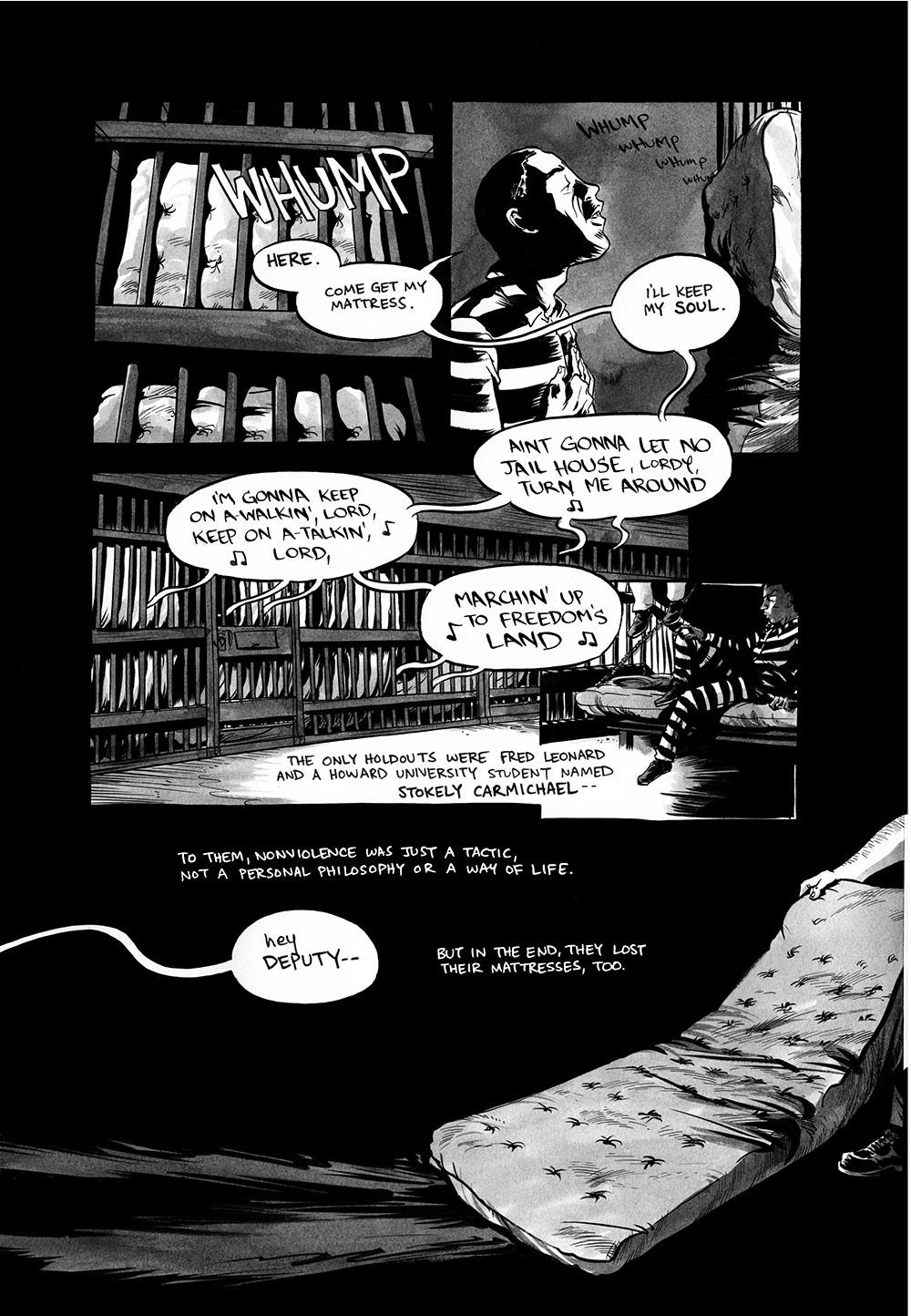

A lot of people don’t realize that one of the reasons John Lewis got into the civil rights movement was because of a comic, right? The Montgomery Story And it seems like your covers, and the color choices were emulating The Montgomery Story

NATE: Yes, Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story was the impetus for March It was this 1957 comic that teenage John Lewis used as a training primer in nonviolence workshops in Nashville. Dr. King and other early nonviolence leaders distributed the comic out of the trunks of their cars and in church basements during training sessions. It directly impacted not only the civil rights movement but also a variety of justice, equality and pro-democracy movements throughout the world, like Cesar Chavez’s labor movement…. It even had bootleg translations in Arabic and Farsi during the lead up to the Arab Spring in 2010 and 2011. It has a fascinating history of its own, and that history is still alive.

One of the big reasons why March happened was because John Lewis told Andrew about this comic’s role in his legacy and how baffled he was that this

level of significance would essentially be relegated to obscurity.

KEITH: It’s really well written, and drawn, I think, by an anonymous illustrator.

NATE: Andrew did his graduate thesis at Georgetown on that comic, and in 2018, he actually had a face-to-face meeting at Dragon Con with cartoonist Sy Barry and confirmed that he was, in fact, the artist on the book. But it was a Silver Age book, and oftentimes creators were entirely uncredited.

KEITH: Now March is read all around the world and is on so many syllabi in high schools and colleges. It’s so neat to see March on bookshelves behind people talking on MSNBC. At the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, I had a meeting with Judy Baca, the great Latinx muralist. I walked in and turned the corner, and behind her desk, she had a blow-up of one of the pages from March

NATE: A county defender in Minnesota used March: Book One to be sworn into office just this year.

KEITH: I had Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly come to talk to my students at USC about the subversive power of comics and to talk about Maus [Spiegelman] realized it’s so important to keep talking about it because we have

to convince 40% of America that Nazis are real, and they exist and they are evil. And they’re in America.

NATE: Comics are a very easy target for this current wave of censorship. People insist on comics being just one thing that they can define in a narrow way. It’s really interesting to butt up this limitless communication tool against the insistence of a lot of unfamiliar people to define it. Comics are a medium and a language on their own.

Last year, when the organized bookban movement started really in earnest, I did some shorter op-ed comics for The Washington Post and for The Nib. Then, I went on the counteroffensive. I made a poster that the American Library Association distributed that provides a simple set of unique strengths that comics has pitted against the unique weaknesses of these book-banners.

I thought it would be nice to be able to define what comics is, how it works, and to know what the benefits are. I think it’s important for comics lovers and creators to go on the offensive and get familiar with how to talk about how comics work and why they are valuable. The older I get, the more I realize that it’s important to recognize when you’re simply out of touch with something and when it’s time to listen, in terms of literacy, in terms of new ways of telling and absorbing stories, and new ways of thinking about the world.

KEITH: Do you have any good advice for young cartoonists?

NATE: The number one thing is to show up. I know that we’ve all had a massive setback, socially and community-wise with the last three years of the pandemic, living in holes scattered across the globe. But it is important that we begin to truly reclaim our community spaces. Comics is an industry and an art form, but comics is also a community.

I toiled and self-published and put out one-off books for, like, 15 years before things really started clicking. But what’s important is that you are ready to spend an entire paycheck getting some convention table space and printing up some comics to sell. A lot of it is about being in the same physical space as other people. Over time, even if you’re not selling very many books, people remember you. Believe it or not, they are already a little familiar with your work. It may not feel like it, but it’s absolutely true. Showing up is really important.

KEITH: Nate, you’ve shown up in every way. You’re keeping at it, making these stories that really matter, for the art of it and for telling stories that make the world a better place.

NATE: Thank you! Another thing is, as you’re working on your big idea and really trying to make it be the thing that

rocks the world … one of the biggest mistakes is betting everything on that one big idea and languishing, sometimes for years, because it’s not hitting. What’s more important is the first question people will ask: “What are you doing next?” People want to know where you’re going from that, and that has a lot more currency than the thing that you’re pitching around to get published. People want to know what’s in the future more than what is in their hands at the comic convention.

The other major thing is … whenever I talk to young people, I try to adjust to the reality of what it means to sign up for higher education and being able to not only pursue their passion but find a way out of a potentially very risky situation in terms of taking on student loan debt. It’s something that can’t be ignored. Very few cartoonists make a full-time living off of comics. And that’s absolutely okay. The vast majority of cartoonists, as you said, have day jobs, whether it’s in the arts or teaching. And this returns to what DIY punk means to me. People feel like they need to make a comic, to let something out or to tell a certain story… It must be made, no matter what it takes, and it’s important to embrace that. What’s important is that the work comes first; the work will find a way. Don’t sweat your work, your big idea, your emerging projects as a means to an end, in terms of paying your rent. Comics is a life journey. Sometimes that takes five or 10 or 15 years. But don’t sweat that. What’s important is what you’re putting on the page.

KEITH: That’s right, that’s the integrity of comics.

NATE: I’m a full-time cartoonist. But that means a different thing for everyone. For me, it means that I do my weird, usually magical realist fiction that has a smaller readership. That’s my real passion project. Then, I have a second project I usually do concurrently that’s nonfiction-based,

“Comics is a life journey. Sometimes that takes five or 10 or 15 years. But don’t sweat that. What’s important is what you’re putting on the page.”

—NATE POWELL

usually with another writer, that mixes more of my worldly concerns and that by balancing those things I’m able to make it. So I put out a lot of books; I think I’m about to put out my nineteenth and twentieth book-length comics in the next year.

But what’s wild is, I’m turning 45 this summer. I’ve got, like, 50 more years. There’s no health insurance or retirement plan for cartoonists. So I’m gonna die at the drawing table.

KEITH: Charles Schulz did that.

NATE: But that’s fine with me, recognizing, like, what do you do when you have 45 or 50 more years of comics to do? This year over the winter, I had a mini existential crisis. For the first time in, like, 25 years, I was like, “I’m out of ideas. Inbox at zero!” But then one day an idea popped into my head. I’ve been noodling at it over the last couple of months, and very recently, I’m like, “Wait a minute. I’m not out of ideas. This is the next book.” I think it’s important to impart to students that this is something that happens along the way, and don’t beat yourself over the head about it.

KEITH: And just love the meditation of doing it. I’m co-editing a book for Fantagraphics, two volumes of outsider cartoonist Frank Johnson’s work. He

KEITH: Sadly, we’re in this politically turbulent time. But as Dr. King said, “The moral arc of justice…” What’s the exact quote?

NATE: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” The important takeaway here is that it does not bend by itself. We bend the arc. So, please, actually show up, and bend the arc.

KEITH: Comics are such a democratic medium, and we need them, seriously, to help save democracy.

NATE: Definitely. Yeah. Not an exaggeration.

was an itinerant musician; he would travel and play banjo on radio stations back in the thirties. But lo and behold, when he died—and his wife didn’t even know—he’d done thousands of pages of comics! He just loved being in that world. It was a meditative space. And it seems like you must be in that space, where it’s your safe zone to be at your drafting table, rendering, right?

NATE: I’m a big believer in compartmentalizing your time. The more I can compartmentalize what I do, the happier I am, instead of trying to live like a chaotic artist, looking for flashes of genius. Once my kids are at school, between nine and three, I do nothing but work furiously, so that I’m able to switch back over to the dad zone for the rest of the day. It has made my studio into such a refuge and such a happy place because I allow myself to leave it at an appropriate time, so that I miss it, and I can’t wait to get back to it.

KEITH: Any last words of wisdom?

NATE : Yeah, just stay loud and stick together. We’re in for a turbulent decade-plus ahead of us. That’s not a joke. But we’re gonna win. The fascists are going to lose. Keep on doing the weird stuff that is [off] kilter. It requires your unique voice, and you just being you.

COMX magazine thanks Nate and Keith for sharing their thoughts and memories with us.

REMEMBERING Diane

Noomin

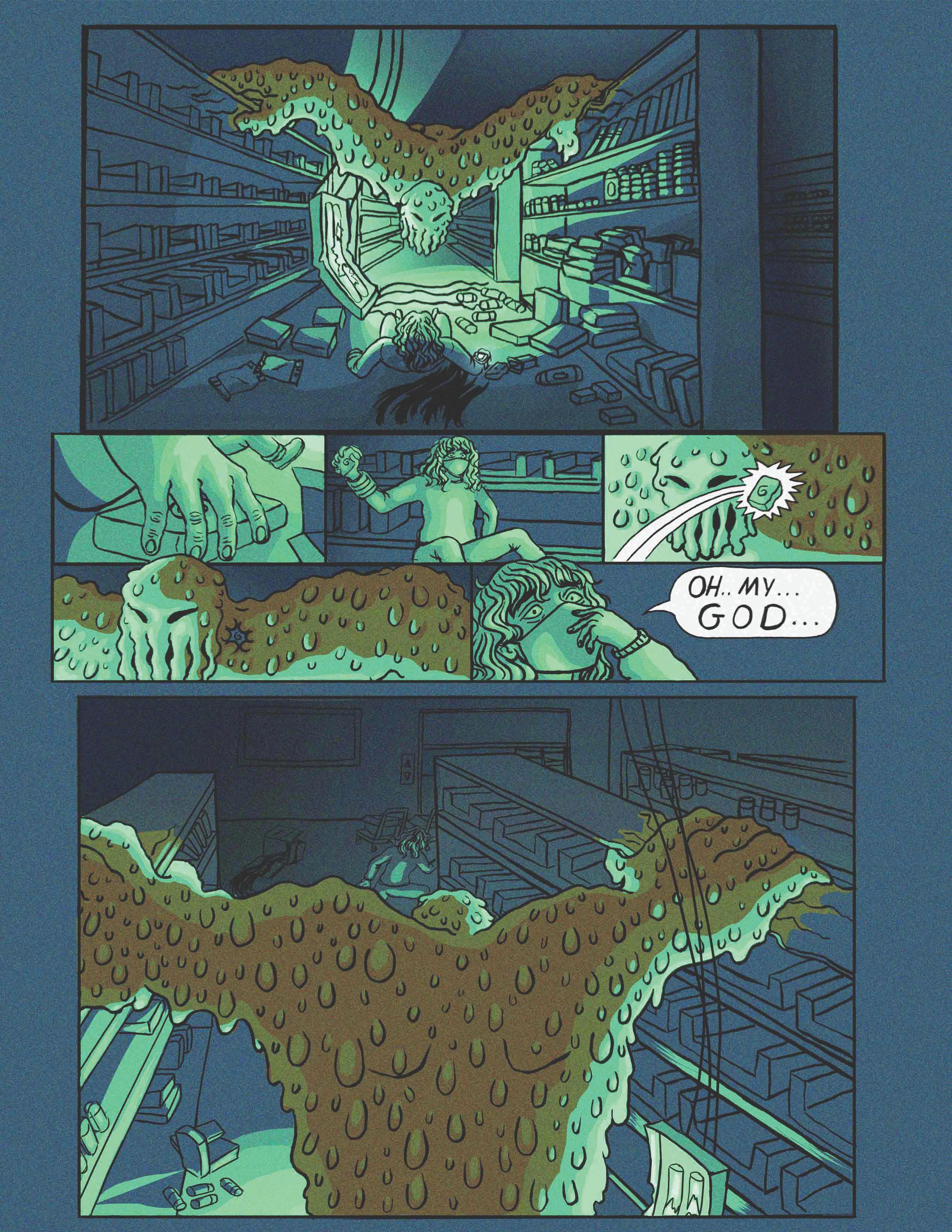

In September 2022, the SVA community lost Diane Noomin, a groundbreaking cartoonist who taught students a subject she nearly pioneered decades ago, “Personal Comics.”

As an artist, Diane is remembered for the body of comics she drew that spoke so eloquently in her own voice. As a teacher, Diane helped SVA Comics students find their voices. And in fact, lifting up the voices of others was a substantial part of her career. In 2019, Diane published her last book, Drawing Power, an anthology of autobiographical comics about sexual harassment and sexual violence featuring personal comics by more than 60 diverse women—including Diane. In her preface, she wrote that the #MeToo movement had motivated her to take on this project. “I’m a cartoonist and an editor,” she wrote. “The only logical way I could respond to this onslaught was as a cartoonist and editor.” It’s important that we remember Diane the way she described herself: as both a cartoonist and an editor.

BY BILL

BY BILL

KARTALOPOULOS

In 1972, Diane was a young art school dropout in San Francisco, filling up notebooks with drawings and poems. By a great stroke of luck, she met Aline Kominsky-Crumb (then Aline Kominsky) at a party, and Aline invited her to the first organizational meeting for Wimmen’s Comix, a collectively run underground comics anthology series exclusively featuring

work by women. When Wimmen’s Comix #1 was published in 1972, it was only the third such publication in American history (after 1970’s It Ain’t Me, Babe and alongside 1972’s Tits and Clits #1). It also proved to be the most long-lasting, publishing 17 issues over 15 years.

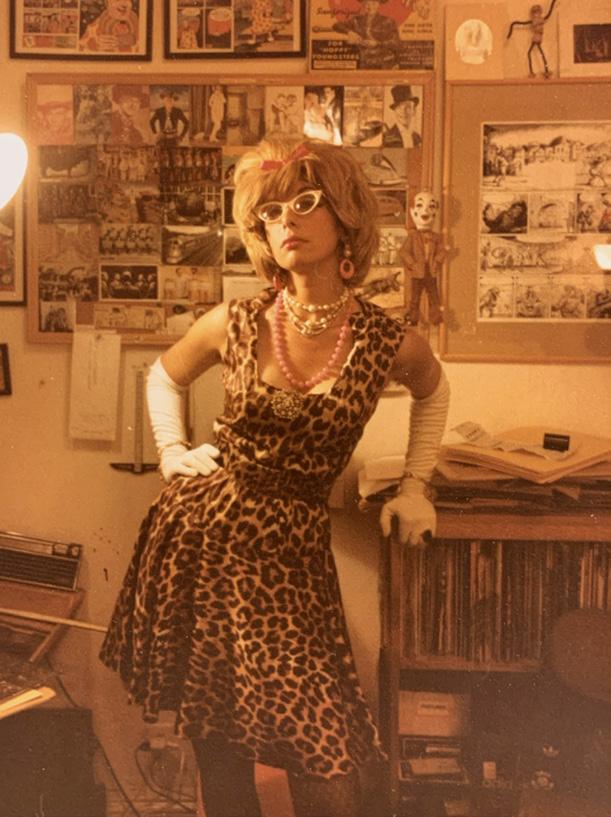

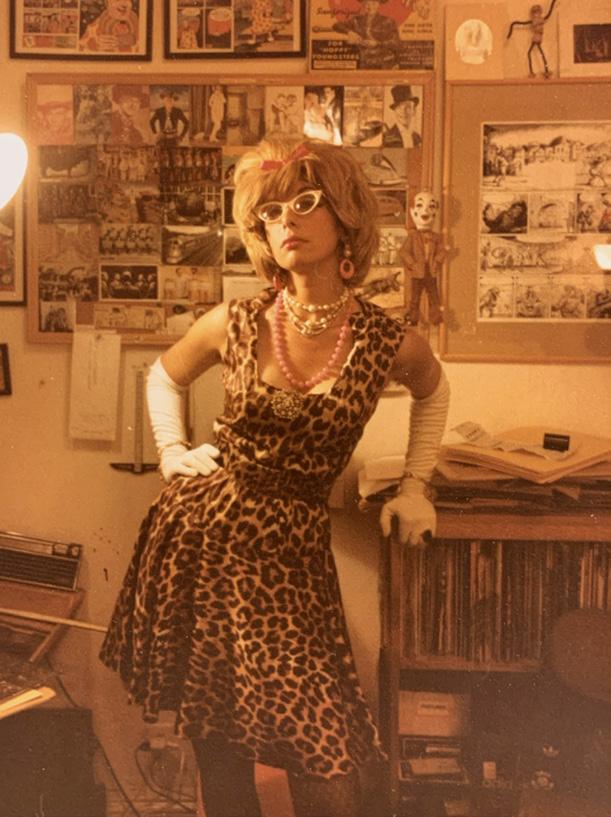

Diane and Aline both published work in early issues of Wimmen’s Comix, but, by 1975, they felt stifled by the perceived pressure to produce work for the publication that upheld the ideals of what was then called the “Women’s Liberation” movement (and which we now identify as second-wave feminism). The following year they broke away from the collective and published their jointly created, one-shot comic book Twisted Sisters. That comic book’s cover greeted readers with a self-portrait by Aline, seen seated on the toilet in a moment of physical self-loathing. Twisted Sisters was a space where Diane and Aline could give full range to their thoughts and feelings—lustful, petty, self-deprecating, joyous and sad—and articulate the full range of their beings without limits. Aline’s stories stuck close to the core of her career-long autobiographical self-exploration in art. Diane spoke to readers through the persona of “DiDi Glitz,” an alter-ego based on the women Noomin had observed growing up on Long Island.

In the years that followed, Diane continued to publish

stories in various comics and edited Lemme Outa Here! (1978), a one-shot anthology satirizing the false dreams and stifling environment of American suburbia. In the years that followed, the underground comix milieu dissipated, and independently motivated comics moved from the magazine racks of “head shops” that catered to countercultural tastes to the back shelves of a rising network of dedicated comic book specialty stores, which principally catered to male collectors of commercial genre comic books.

As a new “alternative” comics scene developed, Diane noticed a rising generation of young women artists publishing their work in independent comics like Weirdo, in magazines like the National Lampoon, in hand-stapled mini-comics, and elsewhere. These women were producing great, individualistic work that exhibited precisely the kind of narrative freedom and aesthetic diversity that motivated Aline and Diane to publish their own comic book in the first place. Diane saw these artists as kindred spirits, fellow twisted sisters. Diane knew this work was good and that it was important, and that it was saying things that weren’t being said in the larger culture. But Diane also perceived that this work was not going to find its ideal appreciative audience languishing in the backs of male-dominated, fan-oriented comic book stores. Diane wanted to show

this work to an outside world of potential readers who might be ready to read adult comics made by talented women speaking impolite truths. So she reinvented Twisted Sisters to create a better platform for their voices.

Against all odds, Diane made a deal with Penguin to publish a book—Twisted Sisters—that would collect work made by women working in the alternative press. That first Twisted Sisters book collection appeared in 1991, and it’s important to understand its significance at that moment. It can be difficult now to remember how few adult-oriented comics were published by mass-market publishers and distributed to mainstream bookstores in 1991. Certainly, Art Spiegelman’s Maus had been very successfully published in two volumes in 1986 and 1991.

Spiegelman and his partner and collaborator Françoise Mouly had already brought their comics anthology series RAW to Penguin and had edited a handful of striking individual book projects at Pantheon and elsewhere, featuring work by Charles Burns, Ben Katchor, Gary Panter, and others. Doubleday had published two collections of Harvey Pekar’s autobiographical American Splendor comics as well as Larry Gonick’s Cartoon History of the Universe. But in 1991, there was little else on the shelves of American bookstores that didn’t look like a Garfield collection or a Batman book.

In that context, it remains striking how uncompromising that first volume of Twisted Sisters was in its editorial choices, anthologizing riveting, risky stories by MK Brown, Julie Doucet, Phoebe Gloeckner, Krystine Kryttre, Dori Seda, and others that had previously been published in comparatively obscure comic books and anthologies. It also remains clear just how seriously Diane took editorial work. She spared no effort to present this work to a potential audience of serious, adult readers who might not otherwise know that these comics even existed—and likely hadn’t thought much about the artistic potential of comics. Twisted Sisters featured blurbs by Spiegelman and Robert Crumb, the two artists making comics for adults who were most likely to be recognized by a general audience. But even further, the book included a blurb by experimental feminist writer Kathy Acker, whose work continues to be rediscovered and studied today, and, across the back cover, in big red letters, an endorsement from pop superstar Madonna, then arguably at the height of her cultural prominence and influence. In securing this promotional quotation, Diane achieved something that even seasoned book publicists can only dream of.

Diane was driven and she pulled out all the stops on behalf of other people’s work. She believed an audience for this work was out there, somewhere beyond the comic book shop. She created a vessel for these comics that was designed to get out into the world, and between the covers, her editorial choices were, as I said, uncompromising. But one compromise is evident: two sexually explicit panels originally published in Young Lust were censored for publication by Penguin. So if Diane was quite early to see the positive potential of working with the mainstream book publishing industry, she also was quick to encounter the downsides of commercial publishing. The book sold out its first print run, but Penguin was in a state of disarray at the time—as corporate publishing companies seem to cyclically be. A new editor-in-chief came in who decided that Penguin was not in the comics publishing business. Clearly, the stigma against comics for adults still persisted in American culture, and so this book that had everything going for it and was selling well did not even go back to press for a second printing.

Nevertheless, Diane still believed in the project and began working on a sequel—this time featuring original work and longer stories. She returned to the independent press, where she knew she would retain full editorial control, and published the second volume of Twisted Sisters in 1994 with Kitchen Sink, one of the few surviving underground comix publishers, and one that had made some inroads into the mainstream book retail marketplace.

As an editor commissioning new work, Diane truly shone in that second volume of Twisted Sisters Working directly for Diane and producing longer stories at her request, some of the artists in Twisted Sisters 2 made comics that are among the best of their careers—certainly up to that point, at the very

least. These include “Sixteen” by Debbie Drechsler, “Minnie’s 3rd Love,” by Phoebe Gloeckner, and Diane’s own autobiographical story “Baby Talk,” in which she stepped out from behind the persona of DiDi Glitz and told her frank and heartbreaking story of multiple unsuccessful attempts to carry a pregnancy to term.

Diane’s two volumes of Twisted Sisters showed anyone who cared to look how good comics by women cartoonists could be. And a few years ago, with Drawing Power, she reminded us how timely and important they could be, too. As an artist, Diane has enriched the world of comics with her smart, funny and emotionally unflinching work. As an editor, she was always a teacher, even before she joined the SVA faculty. We mourn that she is no longer with us. But her work leaves us all with the opportunity to learn from her example: her keen editorial sensibility, her powerful sense of mission, and the uncompromising, deeply motivated drive she brought to all of her work are her inspiring, insistent gifts to us. We can miss her dearly, and we can celebrate that we live in a world that is better because Diane Noomin was here with us, giving us her all.

PHOTO BY BILL GRIFFITH

PHOTO BY BILL GRIFFITH

At the end of this year of teaching, I knew it had been a really good year, one full of discoveries and learning experiences for me. The indicator was: when summer came, instead of dropping school stuff like a hot potato in favor of rest and recreation (you know that teachers look forward to this as much as you do), the first thing I did was look at next fall’s rosters to see if anyone had registered for my classes yet.

Would there be enough enrollment for my classes to run? Would there be some interesting diversity among my students? I looked, and then sighed with relief. All my classes were fully enrolled, with a nice variety of both new and familiar faces, in a great mix of colors and genders. Phew. Good. I get to do this again.

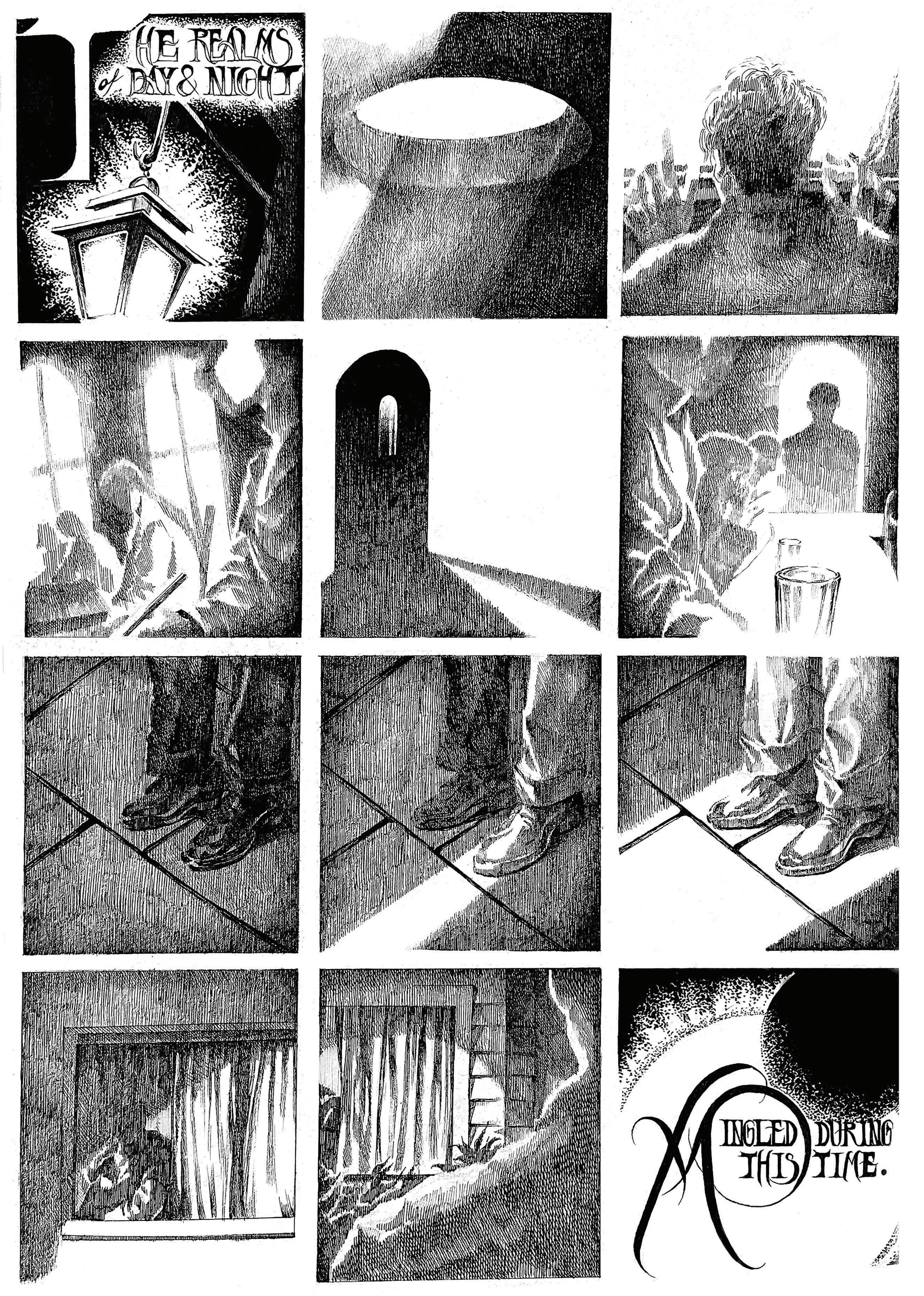

I am very fortunate in that my job is highly addictive. I get to spend my time sharing my enthusiasm for a subject I dearly love—comics. I assign my students comics to read. They read them. Then, they make comics for me to read. Repeat for 30 weeks, with myriad variations.

It helps that comics is such a fantastically layered and eclectic medium. You get out of comics what you put into it, so comics can be childishly simple or thrillingly busy. Comics can be broadly accessible or bizarrely esoteric, highly commercial or defiantly iconoclastic, deeply emotional or brilliantly intellectual. Or any combination of the above and more.

Falling in love with comics means knowing that you will never be bored. You will be too busy for that. There will always be something new to discover… or to invent.

Comics is a collection of nested modular objects: letters within words within balloons within panels within tiers within pages within chapters within books within epic 20-volume shoujo manga series. Plus, of course, some characters and backgrounds. And that nested modularity lends itself to endless creative and scholarly pursuits.

Falling in love with comics means knowing that you will never be bored. You will be too busy for that. There will always be something new to discover… or to invent.

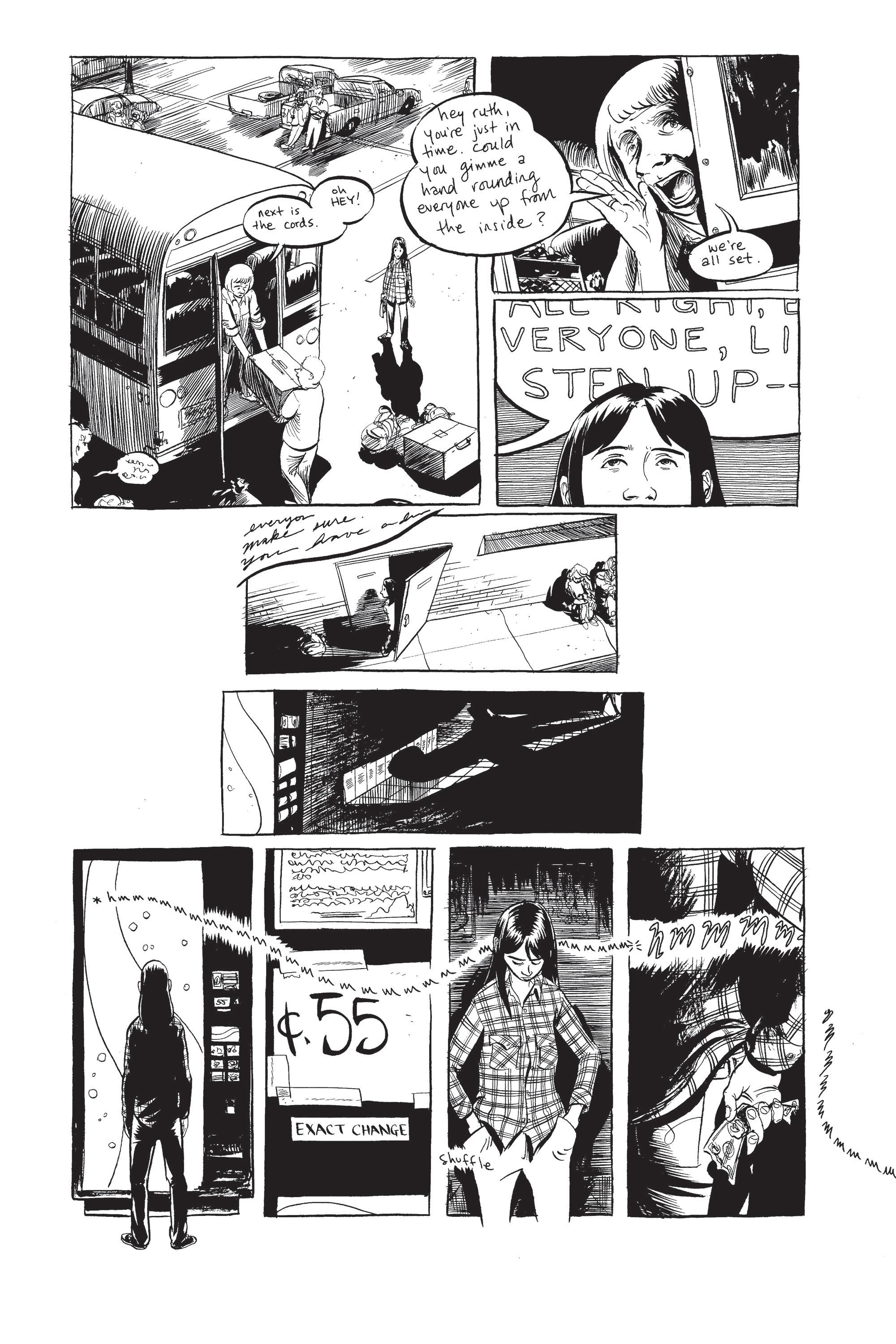

Jason Little BFA Comics Coordinator BFA Comics/BFA Illustration

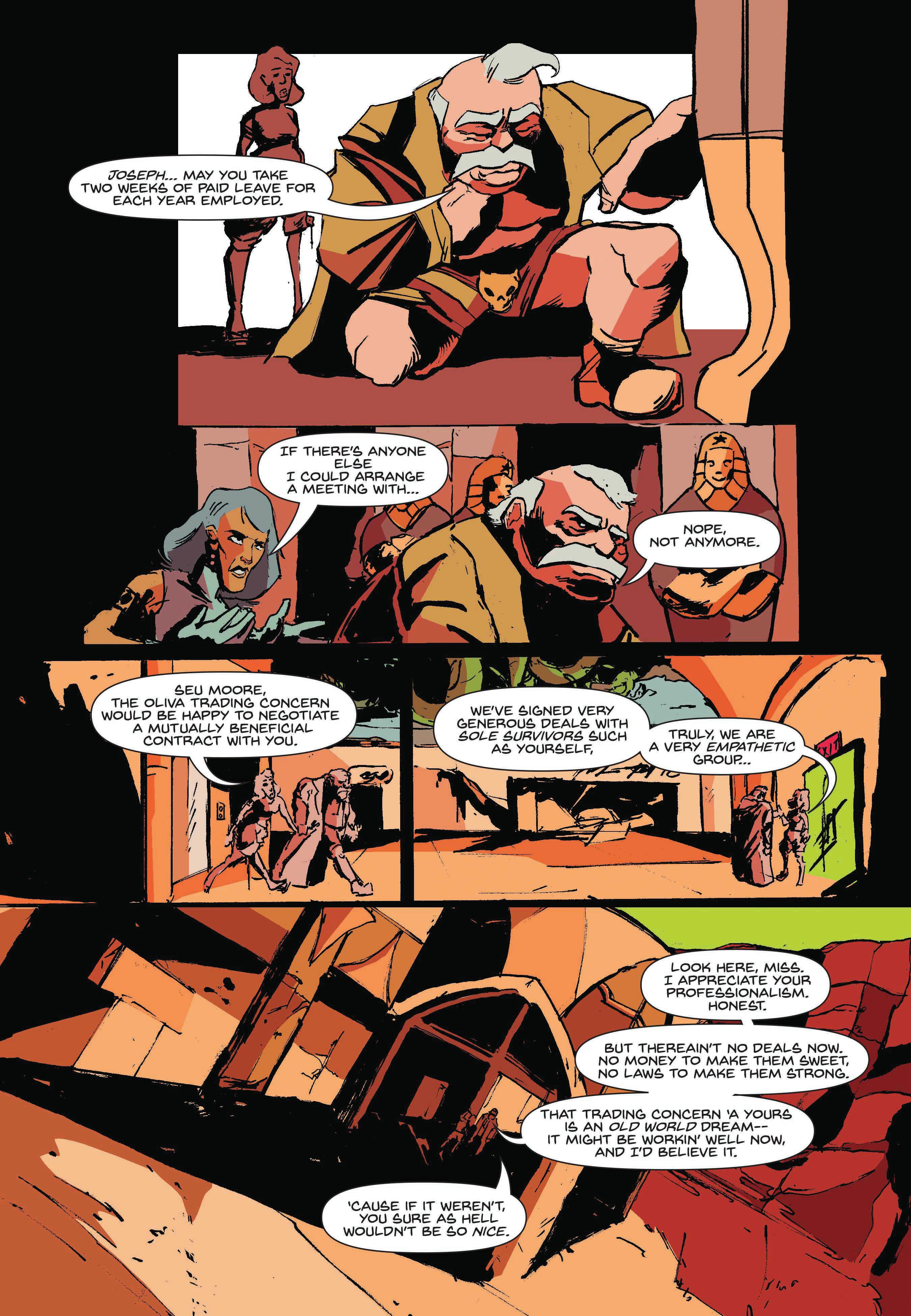

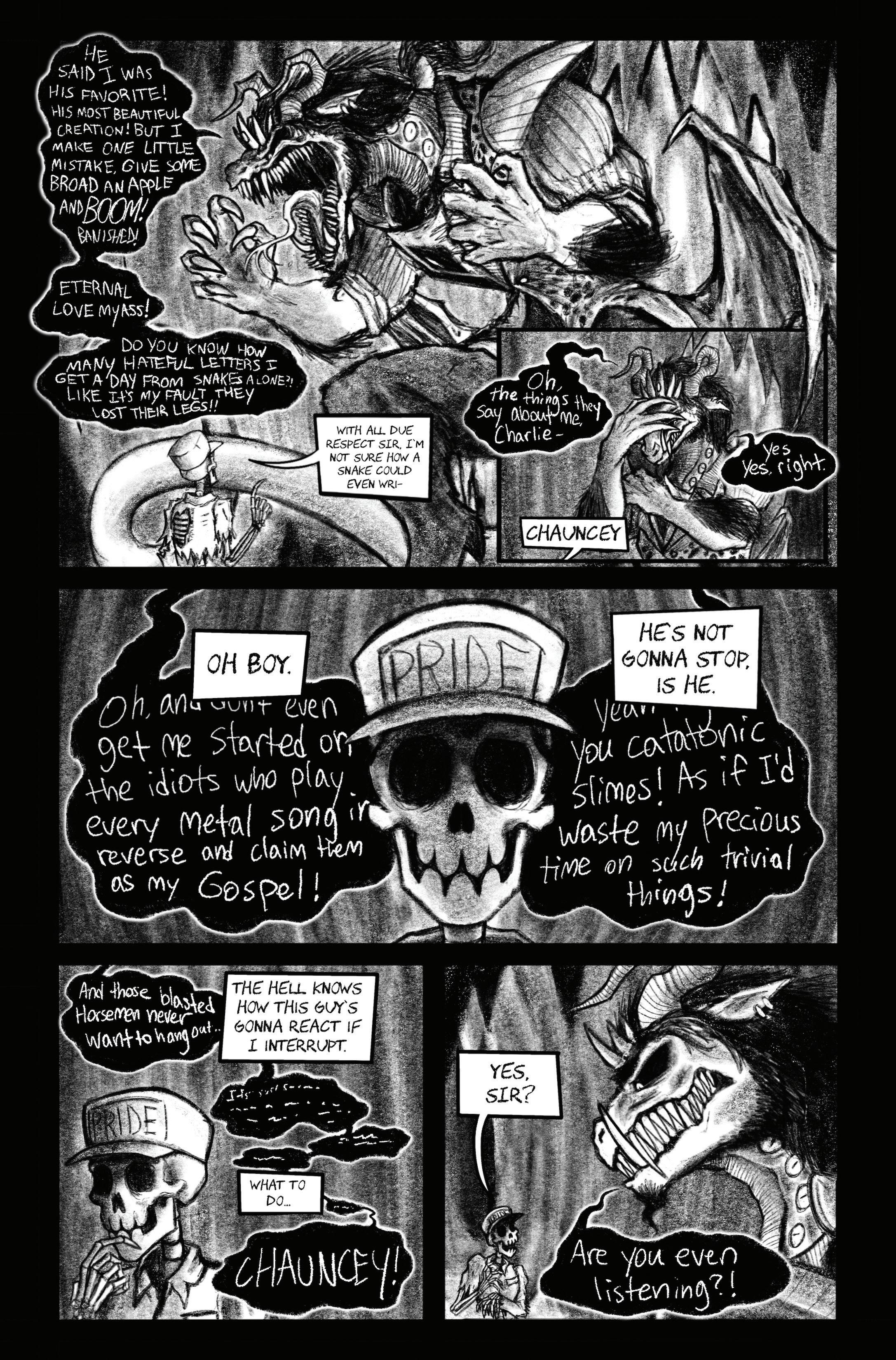

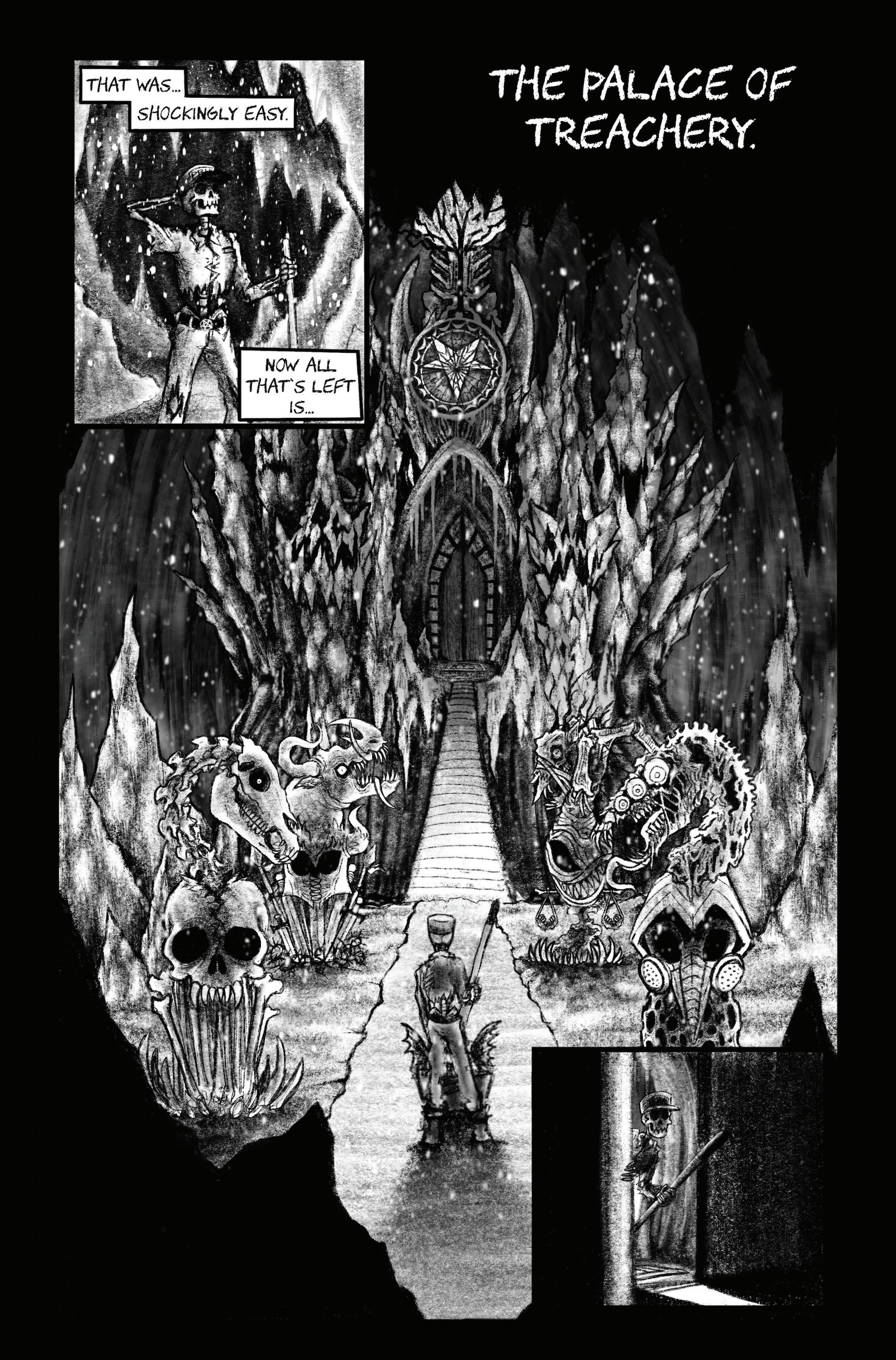

2023 BFA COMICS

FOR THE LOVE OF COMICS

Portfolio Selections

18

Botelho @CABOLGUE 19

Cal

20

21

Freddie Della Famina

22 Natalie Riolfi NATALIERIOLFI.ART 23

24 Kaitlyn Quach @KAITOONIST 25

26

27

Michael Barletta @MBARLETTAART

28 Sinclair Dowty @BROTHBONES 29

30 Nahia Mouhica @PEACHIARE 31

32

JUNIMADII.COM 33

Madelyn Sackett

34

@JUDGEDARTS 35

Yeabin Lee

36 Marko Palushi @VEDAS_VIRTUE 37

38

@XEO.P 39

Xiomara

Pardo Reyes

40 Zhiyu Lin @RABBITVJL.JPG 41

42 Zhiyu Lin @RABBITVJL.JPG 43 Allison Doll ALLISONDOLL.COM

44

45

Koby Clarke

@SKUNKIDD_

@YOONTOONS

Gloria Lee

46

@SABRINANIGHTMAREN 47

Sabrina Reyes

@APOLLOCORED

Apollo Baltazar

48

Van Doren @IANVANDOREN 49 Ariel Lachance @ARIELM.ART

Ian

50 Spark Park @SPARKXART 51 Yoo Jin Ko @JUDY_LOLOL

52

@CAFE.CADET 53

Mason @ANGRYJAZ

Sarah Langston

Jaz

54 Aiden Franco @MOONYMOSS 55 Cat Kaiser CATKAISERART.COM

• COMICS

Keith Mayerson in conversation with Nate Powell + Remembering Diane Noomin by Bill Kartalopoulos

BFA

2O23

BY BILL

BY BILL

PHOTO BY BILL GRIFFITH

PHOTO BY BILL GRIFFITH