Report of the

The state of plastics circularity in Finland 2025

Review and evaluation of PlastLIFE SIP phase 1

Milja Räisänen, Helena Dahlbo, Petra Rinne, Annika Johansson, Tommi Tikkanen, Joanna Haahti, Jani Salminen, Susanna Horn, Jáchym Judl, Jaakko Karvonen, Hanna Salmenperä, Petrus Kautto, Sari Kauppi, Waltteri Heikkilä, Johanna Kaunisto, Tiina Karppinen

Report of the PlastLIFE project coordinated by the Finnish Environment Institute

The state of plastics circularity in Finland 2025

Review and evaluation of PlastLIFE SIP phase 1

Milja Räisänen, Helena Dahlbo, Petra Rinne, Annika Johansson, Tommi Tikkanen, Joanna Haahti, Jani Salminen, Susanna Horn, Jáchym Judl, Jaakko Karvonen, Hanna Salmenperä, Petrus Kautto, Sari Kauppi, Waltteri Heikkilä, Johanna Kaunisto, Tiina Karppinen

Report of the PlastLIFE project coordinated by the Finnish Environment Institute

The state of plastics circularity in Finland 2025

Review and evaluation of PlastLIFE SIP phase 1

Authors:

Milja Räisänen, Helena Dahlbo, Petra Rinne, Annika Johansson, Tommi Tikkanen, Joanna Haahti, Jani Salminen, Susanna Horn, Jáchym Judl, Jaakko Karvonen, Hanna Salmenperä, Petrus Kautto, Sari Kauppi, Waltteri Heikkilä, Johanna Kaunisto, Tiina Karppinen1)

1) Finnish Environment Institute

Co-funder: EU LIFE SIP - funding programme

Publisher: Finnish Environment Institute (Syke), syke.fi/en

Cover photo: Andika Nur / Adobe Stock

The online publication (pdf) is available in the internet: plastlife.fi (in English) >

Circular economy research > Publications on the circular economy, and in Helda open repository (helda.helsinki.fi) Syke-hankkeiden julkaisuja -collection.

ISBN 978-952-11-5808-7 (pdf)

Year of issue: 2025

Preface

Re-thinking plastics in a sustainable circular economy – PlastLIFE SIP (Strategic Integrated Project) is an extensive national co-operation project promoting the implementation of the Plastics Roadmap for Finland (PRfF) and aiming at a sustainable circular economy (CE) for plastics in Finland by 2035. The seven-year project started in December 2022 and will continue until the end of 2029. Altogether 17 partners coordinated by the Finnish Environment Institute (Syke) are working together to develop solutions for

• reducing littering and other negative environmental impacts, and unnecessary consumption of plastics, e.g., by promoting reuse,

• increasing the recycling of plastic waste,

• replacing fossil raw materials in plastics production with recycled plastics or sustainably produced renewable materials, and

• developing the analysis and risk assessment of harmful substances contained in plastic waste.

The PlastLIFE project is mainly funded by the EU LIFE Programme and the partners. Additional funding has been received from several national organisations. More info on the consortium and funding, as well as the project activities can be found from the project webpages at www.plastlife.fi.

This report is produced at the end of the first phase of the project to generate an overview on the current situation of the CE of plastics in Finland as well as PlastLIFE’s and complementary measures’ impacts on the development towards the CE of plastics. Additionally, an evaluation is presented on the PlastLIFE project performance and progress in achieving the various objectives set for the project and the specific activities.

This report will provide comprehensive information for evaluating the PRfF and the planning of the second phase of the PlastLIFE project (2026–2029) and considering the needs for refocusing the project activities as well as mobilising complementary measures. The results can also be utilised in the process of updating the Plastics Roadmap for Finland.

The authors wish to thank everyone who gave their input to the report by providing data or by commenting the report: PlastLIFE consortium members, PlastLIFE steering group, PlastLIFE advisory group, Plastics Roadmap for Finland co-operation network as well as individual experts including Katariina Kukkasniemi, Henna Jylhä, Jaana Sorvari and Tomas Ekvall.

Authors, November 2025

Abstract

The state of plastics circularity in Finland 2025 - Review and evaluation of PlastLIFE SIP phase 1

Re-thinking plastics in a sustainable circular economy – PlastLIFE SIP (Strategic Integrated Project, 2022–2029) aims at a sustainable circular economy (CE) for plastics in Finland by 2035. PlastLIFE promotes the implementation of the Plastics Roadmap for Finland (PRfF) by reducing littering and other negative impacts of plastics, refusing from unnecessary consumption of plastics and promoting reuse, increasing recycling and replacing fossil raw material with renewable or recycled materials.

This report presents an overview of the CE of plastics in Finland at the end of the 1st phase of PlastLIFE. It highlights future priorities for promoting the CE and identifies the needs for additional activities within PlastLIFE and related initiatives

PRfF (2018, updated in 2022) and its co-operation network have provided a platform and a shared desire for collaboration between plastics value chain actors and public administration to promote CE of plastics. Yet, achieving CE of plastics still requires continuous efforts across all levels of society

Littering remains a significant problem along Finland’s coasts, where approximately 90% of beach litter consists of plastics. Improving the situation requires more knowledge on litter pathways, as well as the development of methods for identification, monitoring and assessment of impacts.

The greatest challenge in promoting the CE of plastics is reducing unnecessary consumption of plastic, which requires changes in behaviour and the creation of entirely new business environments, for example, to enable reuse and repair. In the plastics value chain, the highest climate impacts occur during material production. Reducing unnecessary plastic consumption mitigates climate impacts, littering, and the spread of hazardous substances into the environment and organisms. So far, the reduction of plastic use has largely relied on voluntary measures, such as Green Deal agreements However, there is either no available data on their effectiveness, or the data that does exist indicates only minimal change. Stronger policy instruments should be considered and monitoring improved

Separately collected plastic packaging waste accounts for less than half of total plastic waste. Around 80% of plastic waste is used for energy recovery, which is the second largest contributor of climate impact in the plastics CE. The focus on packaging leaves most plastic waste streams unaddressed. Data should also be gathered on other plastic waste types, their volumes and recycling potential.

Virgin, fossil-based plastic is increasingly being replaced by alternative materials, such as recycled or bio-based plastics, but monitoring this transition remains challenging. The production of alternative materials is strongly influenced by demand, which has not been high so far. Domestic production also faces challenges due to competition from lower-cost materials available on global markets, where the safety and quality of materials cannot always be ensured.

PlastLIFE will during the 2nd project phase continue to finalise its planned activities and collaborate with relevant stakeholders, especially industry. Focus will increasingly be on communicating, disseminating and scaling up the results. Avoiding unnecessary consumption of plastics and increasing reuse shall get more emphasis. Tailored content in communications and events for different audiences helps reach decision-makers, industry and citizens. Participatory communication campaigns will encourage citizens to get involved in promoting CE of plastics.

The future policy efforts to support the CE of plastics should consider the safety of plastics, prevention of plastic emissions and the quality of recycled plastic. Simultaneously, innovation and new business opportunities should be encouraged, e.g., to support reuse. Developing a comprehensive indicator framework is a requirement for monitoring the progress. Finally, securing funding for research is essential to ensure that decision making is based on scientific evidence and that policy instruments are appropriately targeted and effective in the transition towards the CE of plastics.

Keywords: Plastics, circular economy, PlastLIFE, indicators, plastic flows, LCA, policy, future needs

Tiivistelmä

Muovien kiertotalouden tilanne Suomessa 2025

– PlastLIFE SIP -hankkeen ensimmäisen vaiheen arviointi

Muovien kestävä kiertotalous – PlastLIFE SIP (Strategic Integrated Project 2022–2029) tähtää muovien kestävään kiertotalouteen Suomessa vuoteen 2035 mennessä. PlastLIFE edistää Suomen muovitiekartan (engl. lyhenne PRfF) toimeenpanoa vähentämällä roskaantumista ja muita muovien haitallisia vaikutuksia, vähentämällä muovien turhaa kulutusta, edistämällä uudelleenkäyttöä, lisäämällä kierrätystä ja korvaamalla fossiiliset raaka-aineet uusiutuvilla tai kierrätetyillä materiaaleilla.

Tämä raportti luo yleiskuvan muovien kiertotaloudesta Suomessa PlastLIFE-hankkeen ensimmäisen vaiheen lopussa. Raportissa nostetaan esiin muovien kiertotalouden edistämiseksi tulevaisuudessa tarvittavia painopisteitä ja tunnistetaan tarpeita lisätoimille PlastLIFE:ssa ja sitä täydentävissä hankkeissa.

PRfF (2018, päivitetty 2022) ja sen yhteistyöverkosto ovat muodostaneet toimivan pohjan ja tahtotilan yhteistyölle muovien kiertotalouden edistämiseksi muovien arvoketjutoimijoiden ja julkishallinnon kesken Silti muovien kiertotalouden saavuttaminen vaatii edelleen laajoja ja jatkuvia ponnistuksia kaikilla yhteiskunnan tasoilla.

Roskaantuminen on edelleen merkittävä ongelma Suomen rannikoilla, missä noin 90 % rantaroskasta on muovia. Tilanteen parantaminen edellyttää lisää tietoa roskien kulkureiteistä sekä menetelmien kehittämistä niiden tunnistamiseen, seurantaan ja vaikutusten arviointiin.

Suurin haaste muovien kiertotalouden edistämisessä on muovien turhan kulutuksen vähentäminen, mikä vaatii muutoksia käyttäytymiseen sekä täysin uusien liiketoimintaympäristöjen luomista, esimerkiksi tuotteiden uudelleenkäytön ja korjaamisen mahdollistamiseksi. Muovien arvoketjussa suurimmat ilmastovaikutukset syntyvät materiaalin tuotannosta. Muovin turhan kulutuksen vähentäminen vähentää niin ilmastovaikutuksia, roskaantumista kuin haitallisten aineiden kulkeutumista ympäristöön ja eliöihin. Toistaiseksi muovin käytön vähentäminen on perustunut pääasiassa vapaaehtoisiin toimiin, kuten Green Deal -sopimuksiin. Niiden tehokkuudesta on kuitenkin vain vähän tietoa tai havaitut muutokset ovat olleet vähäisiä. Velvoittavampia politiikkatoimia tulisi harkita ja seurantaa parantaa.

Kaikesta muovijätteestä alle puolet on erilliskerättyä muovipakkausjätettä. Noin 80 % muovijätteestä hyödynnetään energiana, mistä aiheutuu toiseksi eniten ilmastovaikutuksia muovien kiertotaloudessa. Suurin osa muovijätevirroista jää nykyisten pakkauksiin keskittyvien tavoitteiden ja tilastoinnin ulkopuolelle. Tietoa tulisi koota myös muista muovijätteistä, niiden määristä ja kierrätyspotentiaalista.

Neitseellistä, fossiilipohjaista muovia korvataan yhä enemmän vaihtoehtoisilla materiaaleilla, kuten kierrätetyillä tai biopohjaisilla muoveilla, mutta siirtymän seuranta on haastavaa. Vaihtoehtoisten materiaalien tuotantoa ohjaa vahvasti kysyntä, joka ei toistaiseksi ole ollut suurta. Kotimainen tuotanto joutuu kilpailemaan kansainvälisillä markkinoilla esiintyvien materiaalien kanssa, joiden hinta voi olla edullinen, mutta turvallisuus ja laatu kyseenalainen.

Hankkeen toisessa vaiheessa PlastLIFE jatkaa suunniteltujen toimien toteutusta ja viimeistelyä sekä yhteistyötä keskeisten sidosryhmien, erityisesti teollisuuden, kanssa. Painopiste siirtyy yhä enemmän tulosten viestintään, levittämiseen ja skaalaamiseen. Muovin turhan kulutuksen vähentäminen ja uudelleenkäytön lisääminen saavat enemmän painoarvoa. Eri yleisöille räätälöidyt sisällöt viestinnässä ja tapahtumissa auttavat saavuttamaan päättäjiä, teollisuutta ja kansalaisia. Osallistavat viestintäkampanjat kannustavat kansalaisia tulemaan mukaan muovien kiertotalouden edistämiseen.

Politiikan kehittämisessä tulisi edistää teemoja kuten muovien turvallisuus, päästöjen ehkäisy ja kierrätysmuovin laatu. Samalla tulisi tukea innovaatioita ja uusia liiketoimintamahdollisuuksia. Edistymisen seurantaan tarvitaan kattavien indikaattoreiden kehittämistä. Lopuksi, tutkimusrahoituksen turvaaminen on olennaista, jotta päätöksenteko perustuu tieteelliseen näyttöön ja politiikkatoimet ovat kohdennettuja ja tehokkaita siirtymässä kohti muovien kiertotaloutta.

Asiasanat: Muovi, kiertotalous, PlastLIFE, indikaattorit, muovivirrat, LCA, politiikka, tulevat tarpeet

Sammandrag

Status cirkulär ekonomi för plast i Finland 2025 - Utvärdering av PlastLIFE SIP fas 1

Hållbar cirkulär ekonomi för plast – PlastLIFE SIP (Strategic Integrated Project, 2022–2029) syftar till en hållbar cirkulär ekonomi (CE) för plast i Finland senast år 2035. PlastLIFE främjar genomförandet av Finlands färdplan för plast (PRfF) genom att minska nedskräpning och andra negativa effekter av plast, avstå från onödig plastkonsumtion, främja återanvändning, öka återvinning och ersätta fossila råmaterial med förnybara eller återvunna material.

Denna rapport ger en översikt över CE för plast i Finland vid slutet av den första fasen av PlastLIFE. Rapporten lyftar fram framtida prioriteringar för att främja CE, samt identifierar behov av ytterligare åtgärder inom PlastLIFE och kompletterande projekt

PRfF (2018, uppdaterad 2022) och dess samarbetsnätverk har utgjort en fungerande plattform och en gemensam vilja till samarbete för att främja CE för plast mellan aktörer i plastens värdekedja och den offentliga förvaltningen. Att uppnå CE för plast kräver dock fortsatt insatser på alla samhällsnivåer.

Nedskräpning är fortfarande ett betydande problem längs Finlands kuster, där cirka 90 % av strandskräpet består av plast. Förbättring av situationen krävs mer kunskap om skräpets spridningsvägar samt utveckling av metoder för identifiering, övervakning och bedömning av effekter.

Den största utmaningen för att främja CE för plast är att minska onödig konsumtion av plast, vilket kräver beteendeförändringar och skapandet av helt nya affärsmiljöer, till exempel för att möjliggöra återanvändning och reparation av produkter. Den största klimatpåverkan i plastens värdekedja skapas vid materialproduktion. Minskning av onödig plastkonsumtion hindrar klimatpåverkan, nedskräpning och spridning av farliga ämnen i miljön och organismer. Hittills har minskningen av plastanvändning främst baserats på frivilliga åtgärder, såsom Green Deal-avtal. Det finns dock begränsade data om deras effektivitet eller så har observerade förändringar varit små. Starkare politiska styrmedel bör övervägas och övervakningen förbättras.

Separat insamlat plastförpackningsavfall utgör mindre än hälften av all plast i avfallet. Cirka 80 % av allt plastavfall utnyttjas som energi, vilket framkallar den näst största klimatpåverkan inom CE för plast. Största delen av plastavfallet faller utanför de nuvarande förpackningsfokuserade målen och den tillhörande statistiken. Data bör också samlas in om annat plastavfall, deras volymer och återvinningspotential.

Jungfrulig, fossilbaserad plast ersätts alltmer av återvunnen eller biobaserad plast, men övervakningen av denna övergång är utmanande. Produktionen av alternativa material påverkas starkt av efterfrågan, som hittills varit låg. Inhemsk produktion måste konkurrera med material på de internationella marknaderna, vars pris kan vara lågt men där säkerheten och kvaliteten kan ifrågasättas.

Under projektets andra fas kommer PlastLIFE att fortsätta slutföra planerade aktiviteter och samarbeta med relevanta aktörer, särskilt industrin. Fokus kommer alltmer att ligga på kommunikation, spridning och skalning av resultaten. Att undvika onödig plastkonsumtion och öka återanvändning kommer att få större betoning. Skräddarsydda kommunikationsinnehåll och evenemang för olika målgrupper kommer att hjälpa nå beslutsfattare, industri och medborgare. Kommunikationsinsatser såsom engagerande kampanjer kommer att uppmuntra medborgare att delta i främjandet av CE för plast.

Framtida politiska insatser för att stödja CE för plast bör beakta plastens säkerhet, förebyggande av plastutsläpp och kvaliteten på återvunnen plast. Samtidigt bör innovation och nya affärsmöjligheter uppmuntras, t.ex. för att stödja återanvändning. Slutligen är utvecklingen av ett omfattande indikatorramverk en förutsättning för att följa framstegen. Att säkra finansiering för forskning är avgörande för att säkerställa att beslutsfattande baseras på vetenskapliga bevis och att politiska styrmedel är ändamålsenliga och effektiva i övergången mot CE för plast.

Nyckelord: Plast, cirkulär ekonomi, PlastLIFE, indikatorer, plastflöden, LCA, politik, framtida behov

2.4.

5

5.1.3.

5.1.4.

5.2.

Annex 1. PlastLIFE indicators, their basic and monitoring values and data sources.

Annex 2. Deliverables and other publications produced in the PlastLIFE SIP (2022–2025) .................. 111

Annex 3. Complementary measures started 2021–2024 promoting the implementation of the Plastics Roadmap for Finland 115

1 Introduction

Re-thinking plastics in a sustainable circular economy – PlastLIFE SIP (Strategic Integrated Project) is an extensive Finnish national co-operation project with the goal of sustainable circular economy (CE) for plastics in Finland by 2035. During seven years (2022–2029), PlastLIFE promotes the implementation of the Plastics Roadmap for Finland (PRfF) that aims for the breakthrough of a CE of plastics in Finland by 2030 by reducing littering and unnecessary consumption of plastic, increasing recycling and replacing fossil raw material with renewable materials in plastics manufacturing (Ministry of the Environment 2022).

The first steps towards a sustainable plastics economy in Finland were taken in 2018, when the first PRfF was published. The first PRfF was proposed by the wide working group appointed by the Ministry of the Environment (MoE). This national programme aimed at reducing littering and harmful impacts of plastics and decreasing use of unnecessary, especially, single-use plastics. The aim was also to increase recycling and to replace fossil-based plastics with recycled plastics or sustainably produced renewable raw materials (Ministry of the Environment 2022). PlastLIFE was based on the first version of the PRfF.

The update, the Plastics Roadmap 2.0 was again launched by the MoE and published in 2022 by the PRfF co-operation network and as a strategic project of the ministries. The four goals - reduce and refuse, recycle and replace - remained but there were other new goals added to the programme because this was suggested in the mid-term review and evaluation of the original Roadmap. The main goal was specified and set to ensure the breakthrough of a circular plastics economy in Finland by 2030. Along this main goal several suggested first steps needed were set for each action.

The PlastLIFE project was originally structured to promote the implementation of the first version of the PRfF, in which the explanations for the four main objectives reduce and refuse, recycle and replace, had slightly different phrasings than in the second version (O1-O4, Chapter 1.1). However, the main contents remained the same. During the project implementation, PlastLIFE follows closely the updates of the PRfF and considers each alteration in the roadmap. Yet no need for specific conversion has been discovered. After all, the main target has remained the same: the aim for a sustainable circular plastics economy in Finland. In this report, for clarity, the current phrasings for the four main PRfF objectives are used (see Chapter 1.1).

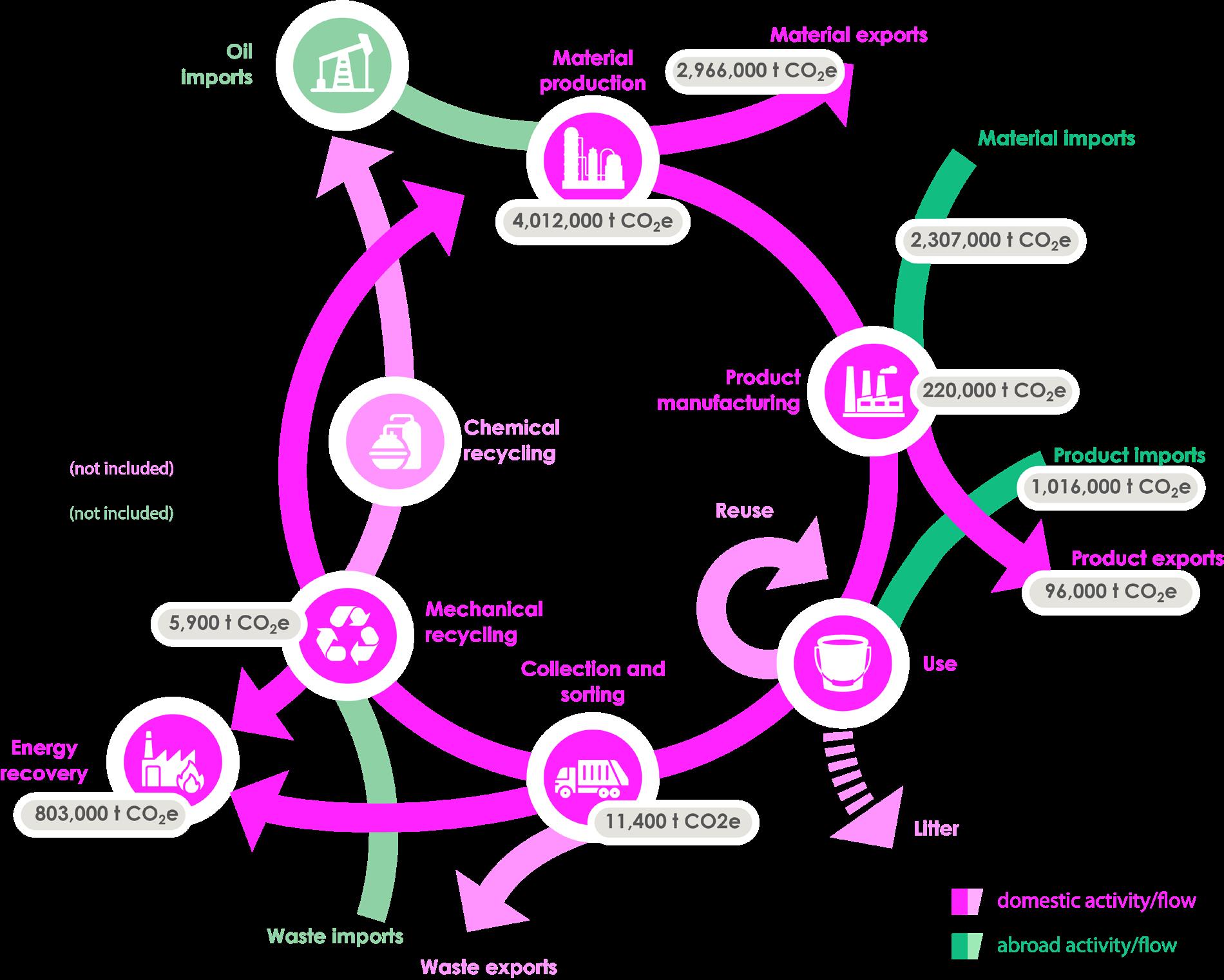

PlastLIFE is divided into two phases: 1st phase 2022–2025 and 2nd phase 2026–2029. The aim of the current report is to examine the situation of the CE of plastics in Finland at the end of the project phase 1. The report evaluates the national development on the CE of plastics in correspondence to the PRfF and its targets (Chapter 2). In addition to the national development, the impacts of PlastLIFE and its complementary measures are analysed in comparison to the targets of the project (Chapters 3 and 4). A comprehensive picture of the plastic flows in Finland is a prerequisite for understanding the current situation and future potentials of the CE of plastics. The plastic flows are reported in Chapter 5 and the environmental impacts of the CE of plastics assessed based on these flows, are reported in Chapter 6. The evolving policy environment of the CE of plastics is discussed in Chapter 7. Finally, conclusions based on these analyses are drawn in Chapter 8 and suggestions for future priorities for promoting the CE of plastics in Finland are given.

The comprehensive report serves as a basis for considering the need for re-directing and modifying the project tasks and for mobilising complementary measures for the project phase 2. The report also

analyses whether more measures are needed on a national and policy level to achieve the sustainable CE of plastics The analysis will be repeated at the end of the project phase 2.

The target audience for this report include 1) the project consortium and financiers for the impacts of the project, and 2) professional audience and general public for the analysis of the national status of CE of plastics and general impacts of the project.

1.1. The Plastics Roadmap paves the way for the breakthrough of the circular economy of plastics in Finland by 2030

According to the Plastics Roadmap for Finland, a breakthrough of CE for plastics by 2030 requires making progress towards reducing littering of the environment and other environmental harm caused by plastics (Objective 1 = O1), avoiding unnecessary consumption of plastics and promoting the reuse of plastics (Objective 2 = O2), enhancing the recycling of plastics and recyclability of plastic products (Objective 3 = O3) and replacing virgin plastic manufactured from fossil raw materials with recycled plastics or sustainably produced renewable materials (Objective 4 = O4) (Ministry of the Environment 2022). Throughout this report, progress in the CE of plastics is described primarily in relation to these four objectives.

In addition to the objectives, the PRfF includes 11 separate action measures. The action packages are set to achieve the following six goals by 2030 (Ministry of the Environment 2022):

• A substantial reduction in the amount of plastic litter in the marine environment and in several other key areas compared to 2022.

• A 30% reduction in consumption and a significant rise in reuse across several key product groups compared to 2022.

• A 60% recycling rate for plastic packaging and a significant start to recycling other plastic products.

• Fully recyclable or reusable plastic packaging, along with a considerable enhancement in recyclability and reuse across various other plastic products

• Recycled plastics accounting for an average of 30% of new products in several product groups.

• Frontrunner in sustainably produced, recyclable products made from renewable raw materials, as well as in plastic-free materials for specific applications.

The eleven action measures (or themes) of PRfF have been slightly modified to the following altogether 15 themes for the use of the PlastLIFE monitoring (especially for the monitoring of outreach and dissemination in Chapter 3.2.1 and for the monitoring of complementary measures in Chapter 4):

1.2. PlastLIFE SIP promotes the implementation of the Plastics Roadmap for Finland

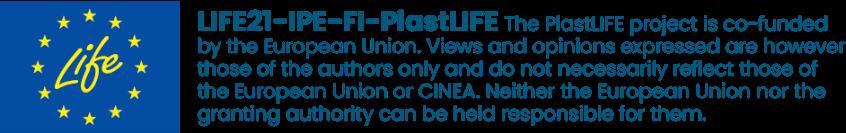

What do we mean by sustainable CE of plastics (Figure 1)? The PlastLIFE project has visioned that a society where sustainable CE of plastics is fulfilled, is a society that takes responsibility for plastics. Everyone feels responsible for plastic use and plastic waste and so does their part to reduce littering and increase plastics recycling. Chemicals are managed in a way that the safe utilisation of plastic waste is ensured, and the development of new alternative materials is safe and sound from all environmental perspectives. For such a society to become a reality, ambitious plastic policies based on scientific knowledge are required, policies that encourage companies to innovate and invest in advancing the CE. Decisions are made based on up-to-date information about different types of plastics, their recycling, and composition as well as their environmental, economic, and social impacts. In a society that takes responsibility for plastics, sustainable solutions and practices are shaped through dialogue and co-operation between key stakeholders.

Figure 1. Sustainable use of natural resources and reduction of negative impacts of plastics are in the core of a sustainable circular economy of plastics. © Finnish Environment Institute. 2025.

To efficiently promote the implementation of the PRfF towards a sustainable CE of plastics, PlastLIFE follows a three-level objective hierarchy ranging from practical, operational objectives to the overarching objectives of the PRfF (see Chapter 1.1). On the first level of the objective hierarchy there are specific task objectives for all PlastLIFE tasks. These task objectives and their indicators are operational and quantifiable or qualitatively assessable. They are monitored during the whole duration of PlastLIFE to assess the impacts of all project activities. The second level of the objective hierarchy includes the overall project objectives, to which the task-level objectives contribute. The project objectives were

defined to monitor the development of the third level of objectives, namely the four overarching objectives of the PRfF (Chapter 1.1).

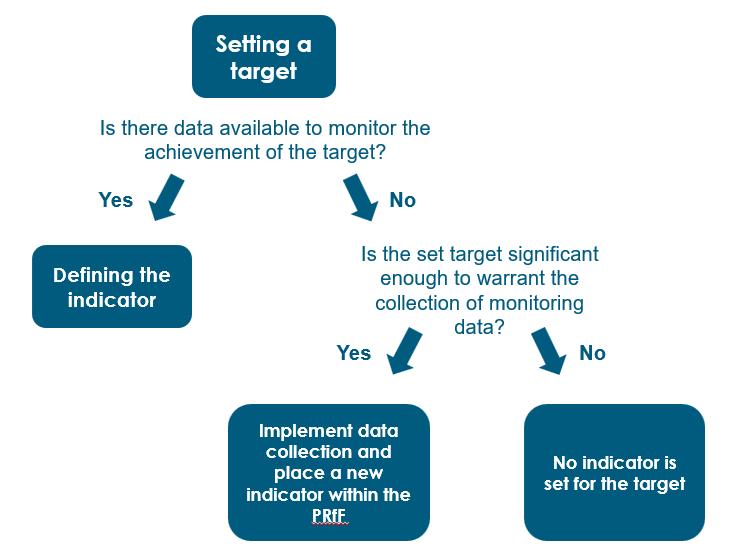

The project objectives and indicators are presented in Tables 1 and 2 together with the relevant target values Most of the targets are set for the year 2035, which marks the end of the PlastLIFE monitoring (five years after the formal conclusion of PlastLIFE in 2029). The cross-cutting project indicators on behaviour, production and consumption, recycling, littering, governance and dissemination generate an understanding of the situation of the CE of plastics in Finland and the impacts of PlastLIFE on it. The indicator baseline values and data sources as well as monitoring values from project phase 1 are presented in Annex 1.

In addition to the indicators in Tables 1 and 2, the project impacts on networking and synergies with other projects, effects on employment, revenue due to project outcomes, and the catalytic effects are monitored during the project lifetime. The indicators and their monitoring values are presented in Annex 1 and not included in the analysis in more details.

Table 1. Indicators and target values for national monitoring selected in PlastLIFE to monitor the circular transition of plastics in Finland.

Objective

1. Reduce littering of the environment and other environmental harm caused by plastics

2. Avoid unnecessary consumption of plastics and promote the reuse of plastics

3. Enhance the recycling of plastics and recyclability of plastic products

Indicator description [unit] Target

a) Coastal littering number of litter items (median) per 100 m of coastline

b) Number of clean up events

4. Replace virgin plastic manufactured from fossil raw materials with recycled plastics or sustainably produced renewable materials

a) ≤ 25

b) ≥ 88

Amount of municipal solid waste [kg/person] ≤ 629 kg/person

a) Recycling rate of plastic packaging waste [%]

b) Recycled plastic packaging waste [t/year]

c) Share of plastics in the mixed municipal solid waste from households [%]

d) Amount of non-recycled plastic packaging waste [t/year]

e) GHG emissions reported in CO2-eq related to plastics waste treatment

Demand for primary plastics [t/year]

a) ≥ 55 %

b) 73,326 t/year

c) ≤ 10 % (or: 166,000 t/year)

d) ≤ 60,000 t/year

e) Decrease of 50% or from 156,000 to 78,000 t/year of CO2eq. in GHG emissions related to plastics waste treatment.

Original target ≤ 520,000, updated target 674,000 t/year

Table 2. Indicators and target values for monitoring the PlastLIFE impacts on PRfF implementation and outreach achieved.

Indicator theme

Degree of the implementation of the PRfF

Outreach achieved

Indicator description

a) Number of PlastLIFE and complementary projects or actions related to the PRfF main objectives

b) A headline figure of PlastLIFE and complementary funding identified, secured and mobilised related to the PRfF main objectives

a) Number of events organised

b) Number of participants in the events organised

c) Evaluation on the increased knowledge (% of respondents)

d) Number of publications

e) Number of web-site visits

Target

a) Target value not defined

b) 150 M€ mobilised by PlastLIFE

a) 200

b) 10,000

c) 70% of respondents

d) 100 blogs or news articles & 70

reports and articles

e) 20,000

2 National development of the circular economy of plastics

This chapter discusses how the circular economy (CE) of plastics has evolved in correspondence to the Plastics Roadmap for Finland (PRfF). The development of the PlastLIFE indicators (Chapter 1.2) is described and an evaluation of the indicator limitations is provided. Additionally, other potential indicators are highlighted and the results of the project ‘Indicators for the PRfF’ by Karppinen et al. (2025) are outlined.

2.1. Reduce littering of the environment and other environmental harm caused by plastics

The presence of plastic waste in the environment has raised significant concern. Single-use plastic (SUP) products have been recognised as a major contributor to littering, prompting legislative efforts to reduce their usage (2019/904/EU). Therefore, also in the PRfF the majority of actions specifically address SUPs. The goal in the PRfF is that there is a substantial reduction in the amount of plastic litter in the marine environment and in a number of other key areas compared to 2022. The chosen indicators highlight the importance of raising public awareness about littering through communication efforts, as well as citizen-focused campaigns and events. Hence, the progress towards the goal is monitored using indicators such as the numbers of coastal litter and environment clean-up campaigns carried out, along with the reported quantities of litter collected.

One of the action packages in the PRfF focuses on addressing the existing knowledge gaps regarding the environmental and health impacts of microplastics, plastic litter, and harmful substances in both virgin and recycled plastics: Enhancing research knowledge of the negative health and environmental impacts of plastics and solutions to these.

2.1.1. National monitoring of coastal littering

National monitoring of coastal litter has been conducted since 2012 as a part of the monitoring programme of EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD, 2008/56/EC). In Finland, monitoring is conducted three times a year in different parts of the coastline. Monitoring has been carried out by Keep the Archipelago Tidy Association (KAT) under the guidance of the Finnish Environment Institute (Syke). The number of monitored beaches has increased during the years from 8 to 15 and they constitute three different beach types: urban, peri-urban and rural beaches. The unit of measurement is the total number of macrolitter items, i.e. litter > 2.5 cm in size, per 100 m of coastline. All litter found in the survey area is counted and classified according to material and intended use (Haaksi 2012).

In the PlastLIFE project, the aim is to reduce coastal littering by at least 50% during the project. The baseline value is 49 litter items per 100 m of beach, which is the median beach litter abundance for Finland’s Baltic Sea subregion of MSFD for the period 2015–2016 (Hanke et al. 2019). The European

threshold value for marine coastal macrolitter is 20 items per 100 m. The target in the PlastLIFE project is to reduce the amount of macro litter to under 25 items.

Data and methods

The indicator value is derived from the annual national beach litter monitoring and used for MSFD status assessment. This value is directly used as an indicator value in the PlastLIFE monitoring. Indicator value of macrolitter items in 2023 and 2024 describes the median amount of all litter that yearly accumulates on the monitoring sites, including also categories of plastic, rubber and foamed polystyrene, across all beach litter monitoring events (including all monitoring beaches and seasons). Therefore, the indicator value used doesn’t differentiate the different beach types, seasons nor consider litter categories. More detailed analysis was made by Karppinen et al. (2025), the results of which are explained in more detail in Chapter 2.1.3. The calculation method for coastal macrolitter indicator values follow the guidance published by the European Commission (Van Loon et al. 2020). For this report, the monitoring data were received from the researchers of Syke.

Results

The amount of beach litter has decreased since 2015–2016 and from the baseline value for PlastLIFE monitoring (Figure 2). In 2023 and the starting year of the PlastLIFE project, the median value of the litter was 16 per 100 meters of Finnish coastline, which was under the target of 25 litter items of the PlastLIFE project. In 2024, the number increased to 26 litter items.

Number of litter items (all beach types)

Figure 2. Number of litter items per 100 meters of Finnish coastline. Median values represent all beach types and seasons. © Finnish Environment Institute. 2025.

2.1.2. Clean -up events of coastal litter

KAT organised their first beach clean-up and litter collection programme Clean Beach in 2014 (Clean Beach 2025a). The results of the MARLIN (Baltic Marine Litter) project during the years 2011–2013 revealed that Finland’s beaches had the highest amounts of litter of all the beaches included in the study. This result was a driving force to an establishment of Litter-free Beaches – clean-up campaign in 2014, which has been repeated annually since then.

The purpose of the Clean Beach programme is to clean up Finnish beaches, collect information and raise awareness about littering (Clean Beach 2025a). Clean Beach consists of clean-up events which can be organised by anyone who is interested in the subject. The organisers can be, e.g., associations, schools, towns, recreational groups, municipalities, companies and private persons. Clean-up events are not limited to seacoasts but can also be arranged on the coasts of inland waters (Karppinen et al. 2025).

The baseline set in the PlastLIFE project is 68 clean-up events per year (2018) and the target is 88 organised events per year.

Data and methods

In the Clean Beach programme, volunteers play a key role by joining beach cleaning events (Clean Beach 2025b). Different organisers joining the programme report back to KAT on all litter gathered at their clean-up events using a litter collection form. Reported forms allow the Association to track the number of individual clean-up events carried out. This information is used in the PlastLIFE monitoring. Reporting information was received directly from KAT. Only events with litter amounts reported to KAT were considered.

Results

The number of clean-up events reported to the programme has increased since 2014. In 2024, 101 events were organised with reported litter amounts (Figure 3). This exceeded the baseline by 33 and the goal for PlastLIFE monitoring by 13. There has been fluctuation in the number of clean-up events over the years, but overall, the number has been increasing

2.1.3. Results of related assessments and studies

A status assessment of littering of the marine environment should be prepared based on the national monitoring of coastal littering, the amount of microlitter in surface water and bottom sediment, the number of macrolitter on the seafloor and floating in the water column and impacts to marine wildlife. The state of marine litter in Finland was assessed for the first time for the years 2017–2022 (Piepponen et al. 2024). However, only coastal littering was used in the assessment because there is not yet enough data available on the other types of littering to make a status assessment and their monitoring is still under development. Microlitter monitoring in the Finnish marine environment was started in 2020, when samples were collected from surface water and bottom sediment. A new environmental target for marine management regarding seafloor macrolitter monitoring is to have the monitoring method established by 2027 (Ekebom et al. 2023).

The European threshold value for good environmental status for marine litter is 20 pieces of litter per 100 m of coastline. The monitored beach is in a poor state in terms of littering if the threshold value is exceeded. In Finland, there was no overall significant increase in the total amount of beach litter in the monitored coasts in the monitoring period 2017–2022. Regarding microlitter and macrolitter on the seabed, a status assessment could not yet be made. The amount of beach litter in the Gulf of Finland (32.5 pieces per 100 m), the Archipelago Sea (28.8 pieces per 100 m) and the Bothnian Bay (34 piece per 100 m) exceeded the threshold value, and their status was classified as poor in terms of littering. However, the total amount of beach litter decreased between 2012 and 2022 in the Gulf of Finland and the Archipelago Sea. In both areas, the amount of plastic, metal, paper and wooden beach litter decreased, and in the Gulf of Finland and the Bothnian Bay (2015–2022) the number of SUP-products declined. Plastic was the most common material for beach litter and its share varied from 50% in the Bothnian Bay to around 80% of the total amount in the Kvarken and Gulf of Finland. Approximately 90% of the beach litter in Finland consists of plastics. (Piepponen et al. 2024)

The indicator value for coastal littering is derived from yearly beach litter monitoring as described in Chapter 2.1.1. The indicator does not differentiate the different sea areas, beach types, or monitoring seasons, and it considers all litter categories (2012–2022: 80 categories; since 2023 183 categories) This outlook differs from the review by Karppinen et al. (2025), where beach litter was analysed only focusing on the categories of plastic litter, foamed polystyrene and rubber. The same monitoring data has been used as the basis for the analysis, i.e. national monitoring of coastal litter. The development of the number of cigarette butts was examined separately from other plastic litter.

The amount of plastic beach litter was at its highest in 2014, after which the amount decreased (Figure 4A; Karppinen et al. 2025). One reason for the large amount of litter in 2014 was the location of one urban monitoring beach in Pihlajasaari, Helsinki, in the vicinity of the West Metro construction site. A large amount of shock tube detonators was found on the beach causing a high number of plastic items. Nevertheless, shock tube detonators alone do not explain the peak, but there has been more plastic litter in the first years of monitoring. When looking at the average number of plastic litter per different beach type, more plastic litter were found on urban beaches than on peri-urban and rural beaches (Figure 4A–C; Karppinen et al. 2025). The total amount of plastic beach litter has been decreasing on all beach types since the beginning of national monitoring. The numbers of foamed polystyrene and rubber litter have also decreased or remained low.

Figure 4. The average number (pcs=pieces) of plastic, foamed polystyrene and rubber litter on urban (A), peri-urban (B) and rural (C) beaches (1000 m2) in 2012–2024. Source: Karppinen et al. 2025.

The most common plastic litter item on Finnish beaches is a cigarette butt. The number of cigarette butts collected has been declining (Figure 5), but the new calculation method introduced in 2020 for the monitoring of cigarette butts does not allow comparisons of recent years with years prior to 2020. The calculation method of cigarette butts changed in 2020 from a smaller sub-area (10 m x 10 m square) to correspond to the guidelines of the MSFD Technical Group on Marine Litter (Galgani et al. 2023). After 2020 the calculation has been done from the whole monitoring area (min. 10 m x 100 m).

Cigarette butts with filters on beaches (pcs/1000 m2)

Change in calculation method

Urban beach Peri-urban beach Rural beach

Figure 5. The average number (pcs=pieces) of cigarette butts with filters on urban, peri-urban and rural beaches (1000 m2) in 2012–2024. The vertical dashed line denotes the change in the monitoring area. Source: Karppinen et al. 2025.

Other environmental and health harm caused by plastics was investigated by Karppinen et al. (2025), and they focused on the indicators of harmful effects of plastics identified in the PRfF: (I) the microplastics load and its impacts on water bodies and the soil, (II) Finns’ exposure to microplastics and (III) the number of published research concerning the environmental and health impacts of plastics, as well as the comprehensiveness of the topic. These indicators were examined through the published Finnish literature and by analysing their results and comprehensiveness under the specified topic.

According to Karppinen et al. (2025), the effects of microplastics in waterbodies and soil are not monitored regularly. Therefore, the impacts of microplastics to the Finnish environment cannot be estimated based on the existing information, nor can Finns’ exposure to microplastics More research is needed on exposure pathways and both daily and long-term exposure and potential accumulation of microplastics in the body (Fjäder et al. 2022). All in all, individual studies and reports are not sufficient to create an overall picture of the harmful effects of plastic on Finns or different environments in Finland.

A key finding of the review report ‘Harmful environmental and health impact of plastics’ by Fjäder et al. (2022) was that environmental research related to plastics has so far focused heavily on the aquatic environment, and especially on the marine environment, although it is estimated that the majority of plastic emissions are directed to the terrestrial environment. But there is not much research on the actual

environmental effects of microplastics in aquatic environments either, especially in freshwaters, as research focuses on the exposure of marine organisms and the harm caused by exposure.

Microplastic loading and its effects on soil have been studied mainly on agricultural soil or in bottom sediments of waterbodies. The MicrAgri project (2023) focused on microplastics in agricultural soil and their emissions, effects and means of reduction. The results showed that microplastics in soil cause changes in soil properties. Biodegradable plastic and cellulose changed the soil microbial community and at high concentrations reduced the amount of ammonium, nitrate nitrogen and soluble carbon in the soil, and changed the water retention capacity of the soil. In addition, increased microbial activity accelerated the soil carbon dioxide content and can reduce the oxygen content in the soil. The soil's deteriorating oxygen status and water retention may possibly be responsible for the reduced reproduction and oxidative stress of earthworms. The effects of microplastics from PE-film in soil were found to be limited compared to biodegradable plastics, but they were found to increase the stress response of earthworms (Selonen et al. 2023).

2.1.4. Discussion

Although the amount of coastal littering has decreased since 2016, the overall status of beaches in terms of littering has been assessed as poor in three out of five coastal areas in Finland Nationally, further efforts must be made to reduce the amount of litter to achieve the threshold value for good status.

So far, initiatives taken to achieve the goal to reduce littering of the environment and set in the PRfF and PlastLIFE have included monitoring of macrolitter in the marine area and raising public awareness and activity on littering. In the PRfF, the reduction of littering is directly related to the updated Programme of Measures of the Marine Strategy 2022–2027 and to the GD which aims to reduce the consumption of SUP-packaging. For example, actions done in cities and industry and effective waste management were assessed in the programme as the most important measures to prevent environmental littering (Laamanen et al. 2021). However, experts found no clear evidence that existing measures will sufficiently reduce littering to meet goals, noting that the causes of littering remain unclear.

Implementation of the PRfF has certainly increased the visibility of plastic littering and kept the issue of plastics under discussion. Various campaigns and co-operation with organisations that maintain civic activity may have partly contributed to the reduction of coastal littering. The increase in interest and activity among citizens is at least evidenced by the fact that the number of clean-up events reported to the Clean Beach programme has increased since 2014. However, the link between behavioural change and reduced coastal littering is challenging to assess.

The PRfF’s emphasis on the marine environment overlooks large parts of the ecosystem, such as inland waters or beaches and terrestrial habitat, although it is known that the majority of plastic emissions are directed to the terrestrial environment While there is not yet enough data on the other types of littering (etc. microlitter in surface water and bottom sediment) or finalised monitoring methods available, it does not remove the fact that no concrete action has been taken to address macro- or microlittering in other areas. Furthermore, the overall picture of the harmful effects of plastic on humans or different environments in Finland relies on individual studies and surveys, which makes it difficult to develop the necessary solutions to address the problem.

Overall, one programme or project alone cannot solve a major system-level challenge, and focusing on marine areas and influencing citizens' behaviour is not enough for comprehensive change. For example, the obligation to litter monitoring could be added to the Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EY) for inland waters, in line with the inclusion of marine litter monitoring in the MSFD (2008/56/EC). New concrete, innovative and easy-to-reach solutions and experiments are needed to reduce littering and its impacts on the environment.

2.2. Avoid unnecessary consumption of plastics and promote the reuse of plastics

One goal of the PRfF is to reduce unnecessary plastic use, targeting a 30% decrease in consumption by 2030 compared to 2022 levels. The programme defines ‘useful plastics’ as a material that has positive qualities in terms of the environment (Ministry of the Environment 2022). For this reason, what is seen as unnecessary consumption is, for example, the use of plastic in single-use products and overpacking of products. Unnecessary plastic use is often associated with the adverse environmental impacts of plastic, such as pollution caused by SUP-products. Sustainable product design, reuse or the replacement of plastic with other materials are seen as key means of reducing unnecessary plastic consumption. The PRfF defines three key indicators for tracking progress: (1) including data on the reduction in plastic (tonnes) used in single-use portion packages, (2) assurance that the total amount of non-plastic materials in such packaging does not surpass 2022 levels, and (3) monitoring the percentage trend in the use of plastic films within construction supply chains. These have been addressed in various Green Deal (GD) agreements, covering areas such as SUP-packaging, construction plastics, and plastic bags (Chapter 2.2.2).

Plastic consumption is also connected to its end-of-life impacts, such as littering and waste generation. Therefore, the indicator selected in the PlastLIFE is the annual total amount of municipal solid waste (MSW) generated per capita in Finland.

Efforts to promote plastic reuse is tackled in the PRfF by phasing out SUP-products at public events and replacing them with reusable alternatives. As an indicator, the PRfF proposes tracking the number of companies offering reusable food packaging, like cups and containers. Beyond promotional measures, the PRfF also includes a statistical indicator related to the reporting of reusable plastic packaging, which is part of producer responsibility and publicly available. The initial introduction of a reusable package to the market is recorded as 'placed on the market', while its subsequent uses are recorded as 'reused’. There are no statistical data available on the reuse of plastic products other than plastic packaging. (Karppinen et al. 2025)

2.2.1. Amount of municipal solid waste

Official Statistics of Finland publishes the total amount of MSW generated in households and services annually and per capita (Official Statistics of Finland 2025a). The amount is recorded in accordance with the reporting requirements of the Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC).

The PlastLIFE project aims to reduce the amount of municipal waste generated per capita in Finland from the 2021 level of 629 kg.

Data and methods

The amount of MSW generated in years 2021–2023 was reported using the existing data published by Statistics Finland (Official Statistics of Finland 2025a) and compared with the baseline value of 2021. Statistics for 2024 will be published in December 2025.

Results

The amount of MSW has decreased since 2021, from the baseline value for PlastLIFE monitoring (Figure 6). In 2022 the amount of MSW generated was 521 kg per capita, which is 108 kg less than in 2021. In 2023 the amount had decreased to 466 kg per capita. Between 2002 and 2023, the amount has been lower than this only in 2002 and 2003, 458 kg and 465 kg per capita, respectively.

Figure 6. The amount of MSW generated per capita in 2021–2023.

Source: Official Statistics of Finland 2025a.

2.2.2. Results of related measures: Green Deals

There are diverse ways to reduce unnecessary consumption of plastics. Voluntary agreements can be used to guide operators to reduce plastic use. GD agreements are voluntary commitments that are developed to promote the achievement of environmental and sustainable objectives (Ministry of the Environment 2025). The purpose of GDs is to promote or complement the implementation of current legislation. The targets can be set to be more ambitious than laid down by law and at the same time further regulation is avoided. The GD agreement is concluded between the State and parties that have a key role in achieving the desired change, e.g., business operators or public bodies. The voluntary agreements include targets that can be reached in a relatively short term.

There are three national GD agreements that promote reducing unnecessary consumption of plastics: GD on plastic packaging, GD on plastics in construction and GD on plastic bags. The aim of the plastic packaging agreement is to reduce the numbers of single-use cups for beverages and certain food packaging made entirely or partly of plastic (Ministry of the Environment 2025). The target of this agreement is to reduce the amount of plastic litter in the environment and to promote CE The agreement is part of the implementation of the SUP Directive on the reduction of the impact of certain plastic products on the environment. The objective of the GD on plastics in construction is to increase the volume of separately collected plastics from construction and its supply chain, to optimise and minimise the use of plastic film and to increase the use of recycled plastic film in the plastic film production. The GD on plastic bags was developed to support the reduction target set in the Directive (EU) 2015/720 to reduce the use of lightweight plastic bags with thickness of 15–50 microns to less than 40 bags per person per year by 2025. Besides, or in place of it, Member States may decide to stop offering lightweight plastic bags free of charge at retail locations.

Karppinen et al. (2025) examined the implementation of the mentioned GD agreements, excluding GD on plastic bags, and their effects in relation to the main objective refuse of PRfF The impacts of the plastic bag GD have been assessed in an interim report prepared by Syke (Ministry of the Environment 2023). The parties who have joined the GD on plastic packaging and plastic bags select at least a minimum number of measures specified for the sector (Ministry of the Environment 2023, Karppinen et al. 2025). Progress of the measures are followed by indicators defined by participants and reported to a public Sitoumus2050-website. The information obtained from GD public reporting is qualitative and

general in nature and cannot be used on its own to monitor the indicator proposed in the PRfF for plastic packaging. The quantitative data used for monitoring the plastic packaging GD is obtained from producer responsibility reporting starting from 2023. Therefore, the results don’t cover companies outside the producer responsibility. Reporting is required by law under the Government Decree on Packaging and Packaging Waste (1029/2021) from all producers defined as producers of packaging under the Finnish Waste Act (646/2011). Data is collected by Finnish Packaging Recycling Rinki Oy, which is a nonprofit service company owned by Finnish industry and retail trade

Sector-specific coverage targets for the GD agreement have been reached at the end of 2023, and by June 2024, 25 companies had committed to the plastic packaging GD (Sitoumus2050 2025a, Karppinen et al. 2025). The reporting of the amount of plastic used in the plastic packages is implemented through producer responsibility reporting (Karppinen et al. 2025). The reduction in the amount of plastic used in the single-use cups for beverages and certain food packages is compared to the baseline set in the agreement, which is an estimate calculated by Rinki Oy for the year 2022. According to the results, the amount of plastic in food packages has decreased by 50 tonnes and in beverage cups by 6.2 tonnes between 2022 and 2023, equalling to about 1.5% decrease in the total use of plastic (Figure 7).

The amount of plastic used in the single-use cups for beverages 1,000

The amount of plastic used in food packaging

Figure 7. The amount of plastic used in food packages and single-use beverage cups in 2022 and 2023. The data for 2022 are based on an estimate calculated by Rinki Oy. Source: Karppinen et al. 2025 3,183

The GD of plastics in construction concerns plastic films in the construction supply chain and construction. Plastic films refer to polyethylene-based plastics, as well as stretch wrap and shrink wrap plastics used for packaging and indoor protection. Plastic films have been estimated to be a material flow which can significantly increase the reuse and recycling rates of plastics in the construction sector. One goal of the GD is to optimise and reduce the consumption of plastic films in an environmental and sustainable manner. The agreement defines the measures and indicators for monitoring separately by sector for companies, municipalities and organisations and member associations. The agreement is valid until the end of 2027. (Ministry of the Environment 2020)

In the spring of 2023, in contrast to the original plan of the agreement, the construction industry unions and the Ministry of the Environment jointly decided that the parties joining to the agreement will

choose the measures and set the baseline and the goals to the end of 2027 for themselves to follow (Karppinen et al. 2025). The solution made has been affected by challenges related to competition neutrality and the processing of sensitive data. Quantitative targets for the agreement were set in the spring of 2024.

Parties can set quantitative targets for separate collection, reduction of consumption, preparation for reuse and recycling, and portions of plastics films made from recycled materials (Ministry of the Environment 2020). Reporting of the implemented measures and their results is done annually on the Sitoumus2050 website. As a result of the change to the agreement in 2023, the reported data to the public website does not include information on the amount of collected, consumed or recycled plastic films (Karppinen et al. 2025). The baseline and the achievement of the targets by joined parties are reported qualitatively, e.g., accomplished /not accomplished, or yes/no/partially. Thus, the GD agreement does not provide public data on how much the use of plastic films has decreased. According to Karppinen et al. (2025), only one company is publicly committed to reducing the relative consumption of plastic films. In total, there were 22 companies and member associations committed to the agreement in the autumn of 2023

In 2016, the Ministry of the Environment and the Confederation of Finnish Commerce signed a voluntary GD for plastic bags, which aims to achieve the legislative target of less than 40 bags per person per year by 2025. The agreement can be terminated and replaced by legislative measures if desired if the targets set for 2025 are not achieved. Companies committed to the GD on plastic bags must promote the reduction of the consumption of lightweight plastic bags and prevent littering through advice, education, charging for bags, offering alternative shopping bags and product placement at checkouts. These measures mainly derive from the Directive (EU) 2015/720 on reducing the consumption of lightweight plastic carrier bags Companies committed to the GD report the implementation of the measures taken annually on the publicly available website (Sitoumus2050 2025b). The official reporting of plastic bag consumption is part of the producer responsibility reporting obligation and carried out through producer organisations and reported to the Commission annually. Reporting has been carried out since 2018. The consumption of plastic bags per person in 2022 was 64 and in 2023 approximately 61. The consumption volumes per person for 2017–2023 are presented in Figure 8. In light of the statistics, the target set for 2025 is unlikely to be achieved.

Figure 8. The consumption of plastic bags per person per year from 2017 to 2023

Source: Karppinen et al. 2025

2.2.3. Discussion

It seems to be difficult to find the mechanisms or will to reduce the production and consumption of plastics other than the so-called unnecessary plastics. Finland has, along with other Nordic countries, actively contributed to global efforts to tackle plastic pollution. Currently United Nations member states are negotiating a legally binding treaty covering the entire life cycle of plastics. The negotiations started in 2022, and the treaty was scheduled to be finalised in 2025. However, no consensus has yet been found on the treaty. Provisions aimed at reducing the production and consumption of plastics are opposed by oil producing countries that do not want obligations related to the early stages of the plastic life cycle (Farge & Le Poidevin 2025). At this point the negotiations are to be continued, and the contents of the treaty are still open.

The chosen indicator of measuring the total amount of municipal waste does not directly measure the change in the plastic consumption referred to in the main objective O2. The indicator described in Chapter 2.3.3, which specifically tracks the proportion of plastics in mixed household waste, could also be utilised as a relevant indicator here Combining these indicators offers insight into municipal waste trends, as per capita waste alone may not reflect plastic waste changes, whereas the plastic share in mixed waste does.

The unnecessary consumption of plastic is reduced through voluntary GD agreements. However, the progress of the agreements can be monitored quantitatively only if reporting is required through other regulation, e.g., producer responsibility reporting obligation, as the case is with GDs on plastic packaging and on plastic bags. The effectiveness of these agreements is illustrated by how many parties have been committed to the agreement. The coverage of both of these agreements has been assessed as good: all major retailers of plastic carrier bags have committed to the GD on plastic bags (Sitoumus2050 2025b), and one- or two-thirds of the relevant companies and services and most of the domestic packaging manufacturers have committed to the GD on plastic packaging (Sitoumus2050 2025a). It is still an open question how the implementation and effectiveness of the GD agreement on plastics in construction and the reduction of plastic film use will be monitored. In addition, it remains unclear whether the requirement for competition neutrality on such an operating environment could prevent the monitoring of the agreement.

Among the producers subject to the producer responsibility obligations, only some have committed to GD agreements. Therefore, it is difficult to estimate, for example, whether the producer responsibility reporting figures used to monitor the fulfilment of GD for plastic packaging genuinely reflect success of the agreement, as number of participants are not comparable. Furthermore, how to evaluate the effectiveness of GDs on reducing plastic use if the driving force comes from sources outside the agreement such as other regulatory instruments or CE targets. Either way, the reduction of plastic use can be measured on plastic packaging and on plastic bags, and in both cases, the usage has been decreasing. However, the target set for plastic bags is unlikely to be met, which could lead to the agreement being replaced by legislative measures. For plastic packaging, it is too early to assess the success of the agreement.

The objective to reduce unnecessary plastic consumption has shown to be a very difficult issue and needs further actions, as the same observation is made in the analysis of complementary projects (see Chapter 4.2.2), the results of which show that few projects develop solutions to reduce unnecessary plastic consumption or promote reuse. Reducing consumption will be the biggest challenge of the next few decades, requiring abandoning familiar consumption habits and developing completely new business environments.

2.3. Enhance the recycling of plastics and recyclability of plastic products

One goal of the PRfF is to enhance the recycling of plastics. PRfF defines key indicators to monitor the recycling rate of plastic packaging waste and the amount of recycled and non-recycled plastic packaging waste, the indicators also selected in the PlastLIFE. These indicators exist as each Member State is obliged to collect monitoring data on the above-mentioned objectives and report them annually to the Commission under Directive 94/62/EC on packaging and packaging waste. In addition to monitoring the recycling of plastic packaging, indicators have also been selected to monitor the amount of non-recycled plastic packaging. This complies with Council Decision (EU, Euratom) 2020/2053, which requires Member States to determine the financial penalties applicable to non-recycled plastic packaging waste. The recyclability of plastics, like plastic packaging, has a significant impact on achieving recycling targets. This is supported by the target set in the EU Plastics Strategy, according to which all packaging placed on the market must be reusable or easily recyclable by 2030 (European Commission 2018).

The PRfF also aims to promote the recycling of plastics other than packaging. The indicators selected for the PRfF utilises GD monitoring, which were discussed in Chapter 2.2.2. and the amount of plastics in the mixed MSW (Chapter 2.3.3). Karppinen et al. (2025) noted that there is only limited data available for plastics other than packaging, as their recovery and recycling are not monitored separately (Karppinen et al. 2025). Data is currently limited to national statistics on separately collected plastic from municipal waste, information reported under Section 117c of the Waste Act (646/2011), and separate reports.

2.3.1. Recycling rate of plastic packaging waste

The packaging recycling rate is calculated using the amount of recycled packaging waste in relation to the amount of packaging placed on the market in a given year. Due to the short lifespan of packaging, the amount of packaging placed on the market can be considered equal to the amount of packaging waste generated, as outlined in Directive (EU) 2018/852. Each member state is obliged to report the recycling rate annually to the Commission. The reporting enables monitoring of packaging recycling targets set by the EU (50% by 2025 and 55% by 2030, under Directive 94/62/EY).

Data and methods

Packaging is subject to producer responsibility and the companies that import packaged products or package them in Finland have financial responsibility for arranging the recovery and recycling or other waste management of the packages they place on the market (Finnish Waste Act 646/2011). Companies have mainly transferred the practical arrangements to producer organisations, which charge companies according to the amount of packaging they place on the market. Packaging data is collected via the producer responsibility system and published and reported to the Commission by the responsible authority (Pirkanmaa ELY-Centre 2024).

Results

The recycling rate in 2019 was 42% and decreased to 26% by 2020. However, the recycling rates are not comparable due to the change in the calculation method. The method for calculating the recycling rate of packaging waste was refined in 2020. From that year onward, only plastic waste that is processed into new material is counted as recycled. Previously, all separately collected plastic waste was considered recycled, even though it could include incorrectly sorted or non-recyclable material that was

removed during pre-treatment or sorting, before reaching the recycling phase. Additionally, starting in 2020, the statistics must also account for packaging outside the scope of producer responsibility – such as that introduced to the market by free-riders, private imports, or foreign online retailers. The recycling rate has fluctuated, increasing from 29% in 2021 to 31% in 2022 and subsequently decreasing to 29% in 2023 (Figure 9). In this context, it is evident that the 50% recycling target set for 2025 is unlikely to be met.

Recycling rate

Figure 9. The recycling rate of plastic packaging waste between 2019–2023 and the EU target set for 2030 in percentage (%). *The recycling rate of 2019 is not comparable with the recycling rates of 2020–2023 due to the change in the calculation method. Source: Pirkanmaa ELY-Centre. 2024.

2.3.2. Recycled and non-recycled plastic packaging waste

The two indicators selected in PlastLIFE are the recycled amount and the non-recycled amount of plastic packaging waste. EU Member States are required to report both figures to the European Commission in accordance with Directive 94/62/EC and Council Decision 2020/2053. Within PlastLIFE the goal is to increase the volume of recycled plastic packaging waste to 73,326 tonnes, being 55% of the packaging volume placed on the market in 2019. The year 2019 was selected as baseline year because the most recent data available during the project preparation phase was from that year. In comparison, the baseline year 2019 and year 2023 recorded recycling volumes of 56,208 tonnes and 46,595 tonnes, respectively. The same baseline year has been selected for non-recycled plastic packaging waste, and similar comparability issues apply. In 2019, the amount of non-recycled plastic packaging waste was 77,112 tonnes, rising to 112,503 tonnes in 2023. PlastLIFE together with the complementary measures aims to reduce this figure to 60,000 tonnes or less per year.

Data and methods

The data sources used to determine the quantity of recycled plastic packaging waste, and the amount of packaging placed on the market, are discussed in Chapter 2.3.1. as they relate to calculating the recycling rate. In PlastLIFE, the amount of non-recycled plastic packaging waste is defined as the portion of packaging placed on the market that does not enter recycling. An alternative approach would be to estimate the non-recycled amount based on waste analysis (see Chapter 2.3.3)

Results

The data on recycled and non-recycled plastic packaging waste for the years 2019–2023 is presented in Figure 10. Between 2020 and 2023, the amount of recycled plastic packaging waste has remained below the 2019 level of 56,208 tonnes. However, the 2019 figure is not directly comparable due to changes in the calculation methodology introduced in 2020. Since then, the recycled amount has shown a steady increase until 2022: 41,201 tonnes in 2020, 48,448 tonnes in 2021, and 49,283 tonnes in 2022, the amount decreasing to 46,595 in 2023 (Figure 10). However, the PlastLIFE target remains distant—an additional 26,731tonnes must be recycled to reach the goal of 73,326 tonnes.

In contrast, the amount of non-recycled plastic packaging waste has fluctuated during the years under review, making it difficult to identify a clear trend. The amount of non-recycled plastic packaging waste increased significantly from 77,112 tonnes in 2019 to 115,913 tonnes in 2020, largely due to changes in the calculation method. This upward trend continued in 2021, reaching 117,451 tonnes, followed by a slight decrease to 111,490 tonnes in 2022 and 112,503 tonnes in 2023. The PlastLIFE target reducing non-recycled plastic packaging waste to 60,000 tonnes or less remains far out of reach. The amount of unrecycled plastic packaging in 2023 is 52,509 tonnes above the target. Consequently, the target for recycled packaging waste is easier to achieve than the one set for non-recycled waste.

Recycled and non-recycled plastic packaging waste (1,000 t)

Amount of recycled plastic packaging waste (t/year)

Amount of non-recycled plastic packaging waste (t/year)

Figure 10. The amount of recycled and non-recycled plastic packaging waste between 2019–2023 and the target set in the PlastLIFE for 2035 *2019 is not comparable with 2020–2023 due to the change in the calculation method. Source: Pirkanmaa ELY-Centre 2024.

2.3.3. Plastics in the mixed municipal solid waste from households

Official Statistics of Finland (2025b) records the total amount of municipal waste generated annually, but data specifically on the plastic content within this waste is not available. Therefore, composition studies have been used to estimate the plastic content in mixed waste. These studies offer the most precise insights into household municipal waste composition, whereas similar studies for mixed waste from other sectors are less common and thus provide less reliable data (Karppinen et al. 2021). The chosen

indicator in PlastLIFE is the mass percentage of plastic present in mixed household municipal waste and the volume of plastic in mixed MSW. The baseline year selected is 2020, during which plastic was estimated to make up 17% of mixed household waste and mixed MSW to contain 281,981 tonnes of plastic. The target is to reduce the figures to 10% or less or to 166,000 tonnes.

Data and methods

Suomen kiertovoima (KIVO) compiles a national estimate of the composition of mixed household waste based on the most comparable and recent studies since 2006. Composition studies have been carried out by waste facilities in various municipalities. (KIVO 2024)

Official Statistics of Finland (2025b) publishes the amount of MSW and mixed MSW generated in Finland annually. The latest statistics published are from 2023. The statistics do not provide more detailed information on the distribution of waste sources, so it is not possible to divide it into waste produced by households and waste produced by administration, services and business. Salmenperä et al. (2016) has estimated that 65% of the MSW is produced in households and 35% in other sectors. A similar assessment has not been made regarding mixed MSW. For PlastLIFE, the plastic waste indicator utilises the total amount of mixed MSW and data on the composition of mixed MSW from households. The estimate does not consider the possible dirtiness of the plastic, which can be up to 29% of the total weight for packaging in mixed MSW from households (Kaartinen & Aalto 2025). It's important to note that the percentage and the total weight used in the indicator evaluate different waste streams.

Results

Figure 11 shows the estimated share of plastics in mixed household waste in 2020, 2023 and 2024, the years when KIVO published the composition estimates. In 2020, mixed household waste was estimated to contain on average 17% plastic. This proportion rose to 17.8% in the 2023 estimate, before slightly declining to 17.3% in 2024. As a result, there has been no overall reduction since the 2020 baseline, and progress towards achieving the target of reducing plastic content to 10% or less has not been made. However, the range of results from composition studies is wide and in 2024 it was 10.2–23.5%. This shows that even the most optimistic estimate falls short of meeting the target.

Share of plastics in the mixed MSW (%)

Figure 11 The estimated share of plastics in mixed municipal solid waste from household waste in 2020, 2023 and 2024. Source: KIVO 2024

Figure 12 shows the amount of plastic in mixed municipal waste for the years 2020–2023. The estimate for 2020 is based on data about the composition of mixed household waste from that year (17%), while the estimates for the following years use the most recent data available from 2024 (17.3%). The amount of plastic waste in mixed municipal waste increased from 2020 to 2021, after which the amount has decreased. In 2023, mixed municipal waste contained an estimated 208,497 tonnes of plastic. This is 42,497 tonnes more than the target set in PlastLIFE.

The volume of plastic in mixed municipal waste (1,000 t/year)

Figure 12. The estimates for volume of plastic in mixed municipal waste in 2020–2023.

Source: The Official Statistics of Finland 2025b. KIVO 2024.

2.3.4. Results of related assessments and studies

Key questions of plastics recycling (2023–2025) project examined how various underlying factors, such as recycling process efficiency and waste collection practices, influence the overall recycling rate of plastic packaging. The results indicate that the recycling rate is heavily influenced by the waste stream into which plastic packaging is disposed to. Meeting recycling targets requires a higher share of packaging to be directed into separate collection rather than to other waste streams. In a scenario where all packaging ended up in separate collection, the recycling rate was 60–70%. However, since it is unrealistic to expect all packaging to be sorted to separate collection, additional measures are needed, such as extracting packaging from mixed waste and enhancing recycling technology efficiency. The findings highlight that achieving the recycling targets for plastic packaging waste require substantial improvements in the volume of separately collected packaging, the sorting of these collected fractions, the material recovery from sorted fractions, and the output efficiency of recycling facilities. (Salminen et al. 2025). Moreover, Ruokamo et al. (2022) identified inadequate accessibility to waste collection infrastructure as the predominant factor hindering the sorting and recycling of plastic packaging within Finnish households. This observation is corroborated by findings from a more recent household survey conducted as part of PlastLIFE.

There is little information on the recycling of plastics other than packaging, as their recovery and recycling are not monitored separately. Like packaging, vehicles and waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) fall under producer responsibility obligations. However, because recycling targets for these product categories are based on overall product mass, data specific to plastic recycling is not available in the statistics (Salminen et al. 2025). According to Karppinen et al. (2025) some limited data is available through Official Statistics of Finland’s municipal waste statistics, which report the

quantities of separately collected plastic waste by treatment method, a data which partially includes packaging waste (Official Statistics of Finland 2025b).

Karppinen et al. (2025) emphasised that plastic recyclability is a complex issue influenced by multiple factors, including the material composition and separability of plastic products, the efficiency of collection systems, available recycling technologies, the environmental impacts of recycling processes, and market dynamics – such as the competitiveness of recycled materials compared to virgin plastics. Research that comprehensively considers the above-mentioned issues is currently not available. (Karppinen et al. 2025)

Regarding market dynamics and demand for recycled plastics, Ruokamo et al. (2022) suggest that whereas both experiences and preferences related to recycled plastic products are found to be relatively positive among Finnish consumers, product availability and labelling require more attention. Overall, the findings from Ruokamo et al. (2022) imply that there is room in the market for new consumer products made of recycled plastics.

2.3.5. Discussion