3 minute read

FOSTERING HEALTH EQUITY

From reducing disparities to increasing access to pharmacy care

Eliminating Pharmacy Deserts

Advertisement

Pharmacies are an increasingly important point of care for neighborhoods across the U.S. They not only dispense prescription medications but also offer diagnostic, preventive and emergency services. Lack of access to a convenient pharmacy may be an overlooked contributor to persistent racial and ethnic disparities in the use of prescription medications and essential healthcare services within urban areas.

A study by Hygeia Centennial Chair Dima M. Qato and colleagues demonstrated that Black and Latino neighborhoods in the 30 most populous U.S. cities had fewer pharmacies than white or diverse neighborhoods between 2007 and 2015. The team also found that Black and Latino neighborhoods were more likely to experience pharmacy closures compared with other neighborhoods.

“Our findings suggest that addressing disparities in geographic access to pharmacies— including pharmacy closures—is imperative to improving access to essential medications and other healthcare services in segregated minority neighborhoods,” Qato says.

These efforts could include policies that encourage pharmacies to locate in pharmacy deserts, such as increases to Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement rates for pharmacies most at risk for closure.

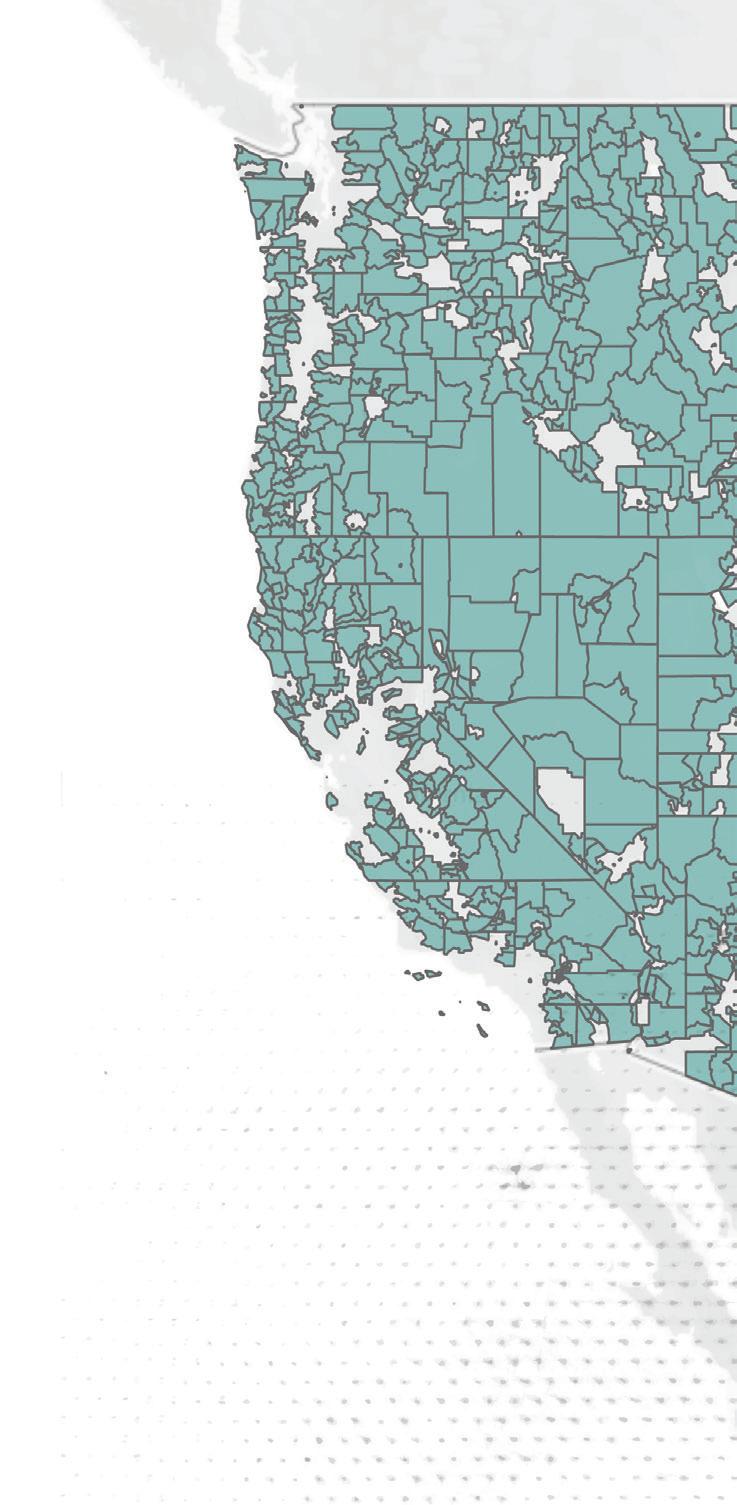

Dima Qato coined the term “pharmacy desert” and is working to ensure access to essential medications and healthcare services in lowincome neighborhoods. This map shows rural pharmacy shortage areas across the continental U.S. in 2020. The aqua color highlights rural pharmacy shortage tracts, where the distance to the nearest pharmacy is greater than 10 miles or a half mile for low-income and low vehicleownership rural tracts.

Over $528 billion of avoidable spending occurs each year in the U.S. due to preventable harm or inadequate treatment from medication, accounting for the thirdleading cause of death. Our goal is to ensure that all patients, particularly those in underserved populations, can attain optimal results from medication therapy, leading to healthier and more productive lives.”

Almost one-third of neighborhoods in the largest U.S. cities were pharmacy deserts in 2015, with Black and Latino neighborhoods disproportionately impacted.

26.7 %

OF WHITE OR DIVERSE NEIGHBORHOODS WERE PHARMACY DESERTS

33 %

OF BLACK NEIGHBORHOODS WERE PHARMACY DESERTS

39.5 %

OF LATINO NEIGHBORHOODS WERE PHARMACY DESERTS

Reducing Disparities in Cancer Detection

Early cancer detection is crucial to enhancing patient survival rates, yet economic obstacles and cultural attitudes can keep Black and Latino patients from undergoing recommended screenings. A study by Darius Lakdawalla and colleagues addressed the benefits of multi-cancer blood-based tests—which do not require a specialist to administer—while also examining the factors driving disparities in health outcomes. Among those factors are insufficient insurance coverage and a lack of trust in healthcare providers that can stem from the disproportionately lower-quality facilities that serve many minority communities. “The promise of these tests will only be realized if we are able to provide broad access to vulnerable populations,” Lakdawalla says.

Addressing Substance Use Disorders

Drug overdose deaths recently hit a record by surpassing 100,000 in a single year. Preventing such tragedies depends on timely access to medications and educating patients, policymakers and healthcare providers to remove unnecessary and stigmatizing barriers to care. Through his research, David Dadiomov aims to remove these barriers so patients can access addiction treatment just as readily as they can access medications for diabetes.

“Viewing addiction disorders in a different light from other medical conditions can cause real personal and public health harms and impede access to treatment,” he says. “It will take the work of individuals, healthcare providers and policymakers to ensure we don’t make the treatment harder to access than the substances themselves.”

Cost-Sharing to Fund Hepatitis C Treatment

Untreated hepatitis C can lead to serious and life-threatening health problems like cirrhosis and liver cancer. Direct-acting antiviral therapies introduced in recent years are highly effective, with cure rates above 95%. But, due to state budget constraints, most Medicaid beneficiaries with hepatitis C don’t get these drugs, which cost $20,000 to $30,000. A study by William Padula published in the American Journal of Managed Care found that a Medicaid–Medicare partnership could cover lifesaving medications—and still save up to $1.1 billion over 25 years. Padula and colleagues developed a model to simulate three different pathways for patients going through the care continuum for hepatitis C. The researchers say their model allows states to calculate the costs and savings of a total coverage policy.

Increasing Access to Medications

Dima M. Qato has garnered national coverage for efforts aimed at widening access to medications and improving prescription adherence. Her work—including a partnership with the National Community Pharmacists Association—has influenced federal and state policies aimed at increasing pharmacy access. She also examines the strain that

$ 1.1 BILLION

POTENTIAL SAVINGS OVER 25 YEARS IF A MEDICAID-MEDICARE PARTNERSHIP COVERED LIFESAVING MEDICATIONS FOR HEPATITIS C polypharmacy—the prescription of multiple drugs for the same conditions—puts on the health of older adults.

Her other collaborations include the World Health Organization, the United States Agency for International Development, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Emory University and University of California, Irvine. Within USC, Qato’s research partners include the Institute on Inequalities in Global Health, the Institute for Addiction Science, the Spatial Sciences Institute, the Keck School of Medicine and the Viterbi School of Engineering.

Her research fosters opportunities for building a pipeline of future researchers as well. “Undergraduates and graduate students at the Mann School and across USC have been increasingly involved in data curation and analysis, including pharmacoepidemiologic big data as well as geospatial analyses,” Qato says.