L

A

B Y N

R T

I H

ISSUE NO. 20 SPRING 2023

Issue No. 20

A complex network of paths in which it is difficult to find one’s way; a wonderlandish maze.

editor in chief kai-lin wei managing director yeonsoo jung

design director jaycee jamison

layout director melanie huynh assistant layout director ava jiang

assistant layout director colin cantwell

director of videography maddie abdalla

graphic design director caroline clark

editorial director amelia kushner

senior print editor kunika trehan

associate print editor carolynn solorio

associate print editor ella rous assistant print editor aaron boehmer

senior web editor ellen daly

associate web editor sonali menon

assistant web editor katlynn fox assistant web editor nysa dharan

creative director alex cao assistant creative director laurence nguyễn-thái

co-director of hmu lily cartagena

co-director of hmu meryl jiang assistant director of hmu averie wang

director of modeling maliabo diamba

assistant director of modeling jillian le assistant director of modeling yousuf khan

director of photography rachel karls

assistant director of photography mateo ontiveros

director of styling vi cao assistant director of styling miguel anderson assistant director of styling saturn eclair tejada

business director jackie fowler

co-director of events divya konkimalla

co-director of events anh tran

director of marketing emely romo

assistant director of marketing brenda chapa

co-director of social media elain yao

co-director of social media olivia abercrombie

assistant director of social media lea boal assistant marketing director brenda chapa

staff

noura abdi, mariana aguirre, brandon akinseye, adreanna alvarez, sophia amstalden, caro arredondo, shreya ayelasomayajula, binny bae, ella baldwin, jeremiah baldwin, eunice bao, ava barrett, zayit barrios, alex basillio, bridget beecham, jean-claude bissou, leah blom, laena bodovsky, chloe bogen, ren breach, charlotte brown, jacqueline bui, jackie bush, leilani cabello, stacey campbell, cristina canepa, via ceaser, katie chang, hayle chen, morgan cheng, candice chepda, victoria cheung, camille chuduc, daniel clenney, cameron coburn, thomas cruz, trisha dasgupta , ale de la fuente, kenneth delucca, lina duchene, seth endsley, anWwna escher, frida espinosa, dakota evans, andreana joi faucette, samantha firmin, alvin fofanah, nia franzua, belton gaar, izabella galindo, liz garcia, elvia garcia, julia garrett, irina griffin, dylan haefner, hafsa haider, safiyya haider, adeline hale, jereamy hall, sara herbowy, audrey hoff, paige hoffer, alex howard-tijerina, tyson humbert, estelle isaac, gabrielle izu, jordyn jackson, rhionna jackson, maddie jewesson, jeffrey jin, rahul kalakuntla, kameel karim, sriya katanguru, payson kelley, maryam khan, joanne kim, annie kim, grace kimball, alija koirala, jane krauss, anjali krishna, tyler kubecka, amy lee, ashley lee, lucy leydon, cynthia lira, luci llano, lauren logan, fernanda lopez, sophia lowe, enrique mancha, liv marbury, catalina marquez, olivia martinez, emily martinez, eric martinez, evelyn martinez, molly masson, anastasia mccants, faith mcnabnay , angela mendiola, mariela mendoza, safa michigan, noa miller, pebbles moomau, nizza morales, kyndal mosley, azucena mosqueda, vivian moyers, arliz muñoz, natán murillo, pranav myana, miles nguyen, maya nguyen, jessica north, kelsey nyandusi, tasmuna omar, emilie opoku, deborah oyawe, bryn palmer, ruth par, river perrill, claire philpot, ainsley plesko, sarah poliuc, athená polymenis, victoria porter, angel quinn, sai veda rallabandi, anagha rao, tarsus rao adeoye, reagan richard, joy richardson, angelynn rivera, julian rodriguez, caitlyn ruiz, renata salazar, nikki shah, vani shah, sonia siddiqui, presley simmons, adalae simpao, peyton sims, isabel sitar, ian saejun smith, caroline st. clergy, ellie stephan, tiffany sun, avani sunkireddy, summer sweeris, katherine tang, leah teague, rachel joy thomas, remy tran, tyler tran, princeton tran, rey tran, andre tran, vianey trejo, vy truong, claire tsui, zayana uddin, cem verploeg, emily wager, eileen wang, gracie warhurst, samuel weiss, wynn wilkinson, xavi williams, melat woldu, megan xie, jonathan xu, grace xu, miranda ye, hairuo yi, elsa zhang

3 spark 1

from the editor Here it comes: the dreaded farewell letter.

To say SPARK has changed my life would be an understatement, and to say that in May, I’ll be able to walk away from it for good without looking once (or twice) over my shoulder would be a lie. I’ve spent most of my college experience uncertain about every aspect of my life, except for the singular adoration I hold for this magazine, sparked (ha ha, one last pun…) almost instantaneously when I first joined staff.

There is, after all, so much to love about SPARK: its gloomy elegance, its rebellious streak, its erudite irony. The well-dressed people! The glitzy book release parties! Most of all, I loved the way it welcomed an entourage of larger-than-life personalities through its metaphorical halls, and that it welcomed me, too — a gawky 18-yearold who had long laid her pen to rest by the time she stumbled across that initial info session in 2019.

As Editor, I’ve certainly grown to love SPARK’s less glamorous, more endearing parts: the cramped general meetings with aisles overflowing with well-dressed people, the breakneck pace of shoot season, and even our Narnia-esque office, with its mountains of cardboard boxes and lockers full of inventory from bygone issues and eras.

We chose “Labyrinth” for our 20th issue concept because, in many ways,

that’s what being a part of something as vast and ever-evolving as SPARK feels like: mazelike, dreamlike, labyrinthine . There will always be something new or interesting waiting for you at the next corner. And no matter how far you go, there will always be more ground to break, more doors behind doors to discover.

During these last four years, this place, this community, and these people have been something of a North Star around which I’ve oriented my creative center of gravity. I say it every season — I’ve said it every season — but I am so, so proud of this one.

Welcome to the Labyrinth. We hope you enjoy your stay.

Sincerely,

Kai-Lin Wei Editor In Chief

2 labyrinth

07 15 23 31 39 47 57 63 69 pulp of my heart pickton, texas once dreamed of snow nostalgic paradise cults of kore outer heaven / inner hell bunny is a rider in search of the perpetual self barbie’s dreamhouse 77 85 95 99 107 113 119 127 135 egodrunk sojourn on sixth m+ fangirl dream of one’s own a bad faith reality material void star-spangled fugue the mouth of the desert R.E.M BLISS contents 3 spark

143 Imani Tatum: sacred skin 153 161 167 175 183 191 197 maneater the high priestess ring of fire vanityinsanity sans issue haunted house! that freeway 207 213 221 227 235 243 249 257 263 needleskull be not afraid katabasis somnum exterreri sell you the world the ritual consuming mortality mosaic of broken everything you, too, shall perish NIGHTMARE END SINISTER FEATURE spark magazine issue no. 20 labyrinth 4 labyrinth

PULP OF MY HEART // PICKTON, TEXAS // NOSTALGIC PARADISE // CULTS OF KORE // IN SEARCH OF THE PERPETUAL SELF // BARBIE’S DREAMHOUSE // OUTER HEAVEN / INNER HELL // BUNNY IS A RIDER // ONCE DREAMED OF SNOW

environment ALEX CAO

PULP OF MY HEART // PICKTON, TEXAS // NOSTALGIC PARADISE // CULTS OF KORE // IN SEARCH OF THE PERPETUAL SELF // BARBIE’S DREAMHOUSE // OUTER HEAVEN / INNER HELL // BUNNY IS A RIDER // ONCE DREAMED OF SNOW

environment ALEX CAO

GATE ONE

BLISS

SHUT YOUR EYES. SUCCUMB TO SACCHARINE FANTASY. LUST, LONGING, AND ECSTASY INTERLACE SWEET FINGERS TO MASK A BLEAK REALITY. HERE, WHERE DESIRE AND MEMORY COLLIDE, YOU SINK INTO VICES LIKE THEY’RE DAYDREAMS. IT’S PARADISE. IT’S SHINING. IT’S ALL YOU CAN SEE.

6 labyrinth

by LUCIA LLANO

by LUCIA LLANO

8 labyrinth

layout EMELY ROMO photographer AMY LEE stylist EMILY MARTINEZ set designers CAROLINE ST. CLERGY & MIGUEL ANDERSON hmua AZUCENA MOSQUEDA & EMELY ROMO models ARLIZ MUÑOZ & TYLER KUBECKA

’m spoiled rotten. my skin so soft. so pretty, go through me like a worm. it’s so easy in the rot of your perfect hands.

you left me here, blind, hands outstretched, murmuring like a fool, calling: darling, darling—you have my whole heart! you have it all darling! my whole, rotten, pink, heart.

white knuckles, or baby’s breath, i overwater, i think, i find myself with fingers in your mouth pulling daisies one by one from your throat.

and you, like oak & ivy you sprout to the touch of me though

the imprint of my fingers makes your skin come apart

but you look so beautiful. i want to pick you even then.

just to feel you, close and little, between my two fingers. even though i make you split in two.

i will love you.

you’re beautiful. you’re honeydew eyes, clementine cheeks, pomegranate lips apple of my eye, your ribs will diverge. your heart, then, open and gaping for me.

you overwater, say,

here is all of me; here is my peach pit here is the pulp of my heart, it is yours, now, –take it. ■

9 spark

i

PEARL NECKLACE | Big Bertha’s Paradise

PEARL NECKLACE | Big Bertha’s Paradise

10

BEJEWELED NECKLACE | Big Bertha’s Paradise SILK SHORTS | Flamingos

labyrinth

11 spark

STRAPLESS JELLYFISH TOP | Emily Martinez

WHITE BLOSSOM SKIRT | Emily Martinez

RUFFLED SCARF | Emily Martinez

HAIR BOWS | Emily Martinez

STRAPLESS JELLYFISH TOP | Emily Martinez

WHITE BLOSSOM SKIRT | Emily Martinez

RUFFLED SCARF | Emily Martinez

HAIR BOWS | Emily Martinez

13 spark

14

labyrinth

Pickton,

15 spark

WHAT BUSINESS DID HANFU-CLAD WOMEN AND LOTUS GARDENS HAVE IN A 1940S TEXAN FARMHOUSE?

Texas

by KATIE CHANG

layout MAYA NGUYEN photographer JEFFREY JIN stylists FAITH MCNABAY & MIRANDA YE hmua SARA HERBOWY & AUDREY HOFF models ELLEN DALY & TARSUS RAO ADEOYE

ickton, Texas, 2014.

The moment I stepped into the house, I wanted to leave. It was as if I’d entered a time capsule, but not the cool type: dingy overhead lighting made the popcorn ceiling super obvious, while wood paneling and red floral wallpaper made the place feel like a haunted dollhouse. It didn’t help that the wallpaper was Asian-themed — I thought the coincidence was a little weird.

Mom told us it was beautiful, but she said a lot of things that didn’t make sense.

We fought constantly — Mom had been away for most of the school year, and at 10, I found her intentions rather confusing. She claimed to want the best for everyone, but I’d watched Dad all year, sallow-faced and sad while he drove me around to all the places she’d always taken me to. If she loved us as she said, why would she leave us for a dusty farmhouse in the middle of nowhere?

It turns out that a decade of suburban housewifery had taken a toll on her, a naturally enterprising woman, and the real tragedy was neither her discarded career or failing marriage. It was her children. No matter how hard she tried to pass down the values instilled in her, her children were growing up to be American kids: kids who expect their lunch to be packed and rides to be covered, who only visit their grandparents during the holidays, who don’t learn what gratitude is until it’s too late.

So, she wanted to change things. I can’t quite recall what she told me, but I remember sitting on the couch the way she hated — on top of the back pillows — when she turned around in her desk chair.

“You know, Mommy grew up on a farm—”

“I know,” I interrupted. I knew where this was going; I had eavesdropped on her and Dad. “I'm not moving schools.”

“Don’t worry about that,” she said, changing the subject. “I found this place that’s not too far. It’s 120 acres and there’s a historic farmhouse right next to a church and…” she trailed off.

“You know, lots of kids raise cows there. They even have a competition. You can win money if—”

“I’m not moving schools,” I interrupted again. “Also, raising a cow is weird.”

As it turns out, raising a cow is weird. It’s also difficult. But that was the point. The point of the farm was to teach us the things Mom learned in her childhood — the things we couldn’t learn from packed lunches and chauffeured rides. She wanted us to know the sulfurous stench of cow shit and the soreness from sowing fields and the stinging of the sun, because there is something beautiful about putting yourself into the fields and putting the fields into your animals and watching your animals bear offspring. There is something beautiful in watching your animals die, too, and returning them to the ground that had long fed them. To be a farmer is to bear witness to the rawest of life — to wake up each morning at the break of dawn and break your back feeding and feeding, but to sit down as the sun dips below the horizon knowing you’ll be fed back.

Or at least that's what Mom told me — I never did raise a cow.

***

Throughout the school year, Mom spent weeks restoring the farmhouse and sowing the ground for the growing season. Every so often, we’d meet her halfway at Cracker Barrel, where she’d tell us how cute the new piglets were and how many veggies she could grow once the USDA approved her grant request. As we’d part ways in the parking lot, she’d always say she wished to come back soon, but there was just so much work to do.

Only later would I realize that the work was much harder than she let on.

The house had been abandoned for a decade, and the family member who’d been helping grew disenchanted, leaving Mom to manage everything alone. Money was tight. Mom tried to come back home as often as possible, but it wasn’t easy — poor people in Pickton were never kind to a house left by city folks.

By the time the grass had grown tall and the piglets fat, I had graduated fifth grade.

P

WHITE DRESS | Flamingos

RED BOOTS | Revival Vintage

RED BELT | Revival Vintage

WHITE DRESS | Flamingos

RED BOOTS | Revival Vintage

RED BELT | Revival Vintage

One afternoon under the limelight of the late summer sun, I strode through the fields behind the house. The wind tangled my hair and tickled my nose with the smell of wild grass, and every step I took set a hundred grasshoppers aside; their wings fluttered in applause, their shrieks rang out in triumph. This was my royal procession, and in my hot pink Nike shorts and Dollar Tree rain boots, I was every bit a queen.

The next day, I was a country singer. Lounging around the chicken coop, I belted out Taylor Swift’s “Never Grow Up” while our dogs barked and my brother searched for eggs. The day after that, I was a bird, chasing my brother (who was a worm) around the church parking lot.

Outside of the house, I was free to be who and what I wanted to be, free from the sound of my parents bickering about finances and parenting philosophy. Outside, I could find plenty of ways to entertain myself.

Besides, no one could babysit but Mom, and she was constantly working.

Only once in a while would Dad come to visit, and those were the days Mom could hand him the handyman work and take us to pick veggies. It wasn’t easy work — my jet-black hair would burn under the sun and my hands would ache from scissors holes and bucket handles — but I recall one evening we all sat down for dinner made from our harvest.

“Mmm, do you taste how fresh the kale is?” Mom asked.

“I hate kale,” I said, my mouth filled with whatever at the table had carbs. In reality, I didn’t mind kale, but I couldn’t tell her that.

“Katherine. It’s good for your brain. Plus, this is the kale we picked.”

My brother perked up. “I like the kale!”

Mom smiled. “That’s mama’s boy. Katherine, even your brother is eating the kale.”

“I’ll eat the tomatoes” I said.

A few minutes later, Dad spoke. He didn’t speak much at dinner.

“Looks like the AC is working well.”

“Yep,” Mom said. “You did a good job with it.”

Dad didn’t reply.

“Did the insurance company get back to you?”

Dad sighed. “No. I told you, the house is old—”

“I know. But someone will cover it.”

***

***

By mid-July the USDA was due to notify Mom about her grant application, but it seemed things were starting to work out on their own. Mom’s veggie garden was so abundant with produce we had to learn how to preserve it all — Mom canned tomatoes, my brother and I made kale chips, and in preparation for the upcoming farmer’s market, Mom bought a blank business name sign for us to decorate with veggie-people and cartoon cows.

At the end of the month, Mom received two manila envelopes. One of them was the approval for the grant. The other was my Dad’s request for a divorce.

All Dad ever wanted was a wife, kids, and a steady

job, and the moment Mom stepped onto the farm, bright-eyed and bold as the cattlemen before her, he knew his dream had come to an end. Every time he’d visit, he’d tell Mom how wonderful her progress was — the hardwood flooring looked great, the greenhouse was impressive — but the more Mom put herself into the farm, the less she left for him. He was losing her.

He didn’t want to lose us too.

Of course, Mom didn’t tell me anything. Dad didn’t either — he wasn’t there. He’d left a few days prior. Soon enough, his gray Honda Fit was in the church parking lot to retrieve me, and then I was home.

We never finished the sign for the farmer’s market.

20 labyrinth

DENIM OVERALLS | Flamingos COWBOY BOOTS | Flamingos FLORAL HEAD SCARF | Flamingos

Pickton, Texas, 2018.

Somewhere around Sulphur Springs on a drive back from the East, Dad turned to me from the driver’s seat.

“We’re pretty close to the farm,” he said. “Do you want to stop by?”

The farm. I, like all of us, avoided any mention of the place. Why would Dad want to visit it now?

“Sure,” I said.

As the sunset cast the world in soft red, we pulled into the church parking lot and headed towards the front door. Dad knocked. The new owners showered us in Southern hospitality.

When I walked in, I expected to see the house I remembered. Mom said the new owners wanted everything as it was—my childhood desk in the bedroom with the patchwork wallpaper, the heater Mom stuck into the fireplace during the winter, even the collection of outdoor decor in the corner of the living room.

But I walked into an American home, Civil War paintings and all. The couches were covered in cowboy-style pillows, the walls in photos of family members and show horses. The only thing I recognized was the wallpaper, that garish wallpaper — fruit motifs for the dining room, florals for the bedrooms, red Chinoiserie for the living room.

I always thought the Chinoiserie was odd, even when I was 10. Really, what business did hanfu-clad women and lotus gardens have in a 1940s Texan farmhouse?

As it turns out, not much. ■

***

CACTUS BOLO TIE | Revival Vintage 22

labyrinth

layout CARO ARREDONDO photographer RACHEL KARLS stylists MIGUEL ANDERSON & JONATHAN XU hmua AVERIE WANG & MERYL JIANG models JILLIAN LE & NOURA ABDI

layout CARO ARREDONDO photographer RACHEL KARLS stylists MIGUEL ANDERSON & JONATHAN XU hmua AVERIE WANG & MERYL JIANG models JILLIAN LE & NOURA ABDI

24

labyrinth

25 spark

26

labyrinth

FUR HAT | Revival Vintage

by EMILIE OPOKU

by EMILIE OPOKU

31 spark

layout AINSLEY PLESKO photographer TYSON HUMBERT stylists SONIA SIDDIQUI & AVANI SUNKIREDDY hmua MARIELA MENDOZA & DEBORAH OYAWE models KELSEY NYANDUSI & ESTELLE ISAAC

32

labyrinth

RED HAT | Prototype Vintage

YELLOW BUTTON UP | Prototype Vintage

RED HAT | Prototype Vintage

YELLOW BUTTON UP | Prototype Vintage

Fresh meat pies sit on the counter, African face masks hang against the walls, lavish beaded jewelry put on display, and the sound of Ghanaian music echoes across the room. The Afribbean market is my mother’s favorite shop for one reason alone: it’s where her dreams begin. I follow her around the store as she starts throwing typical items into the cart – cocoyams, plantain, fufu mix, goat meat, and kobe fish.

At least twice a month, my mother and I go on scavenger hunts. We’ve done this for as long as I’ve been able to walk, and this time is no different than the last.

My mother is notorious for taking hours upon hours to complete simple errands. Time is simply an obscure construct to her – if you’re willing to step out with my mother, you might as well clear your schedule for the entire day. There’s no way to quantify how long the excursion is going to take. She takes as much time as she pleases, collecting everything she needs to return her home. I often find myself riddled with impatience for my mother’s ridiculous shopping habits. But if you ask her, it’s an exhilarating adventure.

While we’re at the market, Serwah’s mind leaves the present and sneaks into a realm of familiarity, into a nostalgic paradise. I’m holding the basket for my mother as she gallivants about the room. She pauses our shopping to make conversation with an old friend from our small community. I shake my head in annoyance. We’ll definitely be here for a minute. They start speaking in Twi, catching up on the usual.

“What are you doing here?”

“How are your kids?”

“When are you going back to Ghana?”

This woman is chatting as if we don’t have a mile long list of groceries.

Joyce Serwah Opoku is the epitome of a Ghanaian woman. My mother grew up along the streets of Ejisu. While she never had much to begin with, her mind has always been one of the most valuable assets known to man. This woman will change for

no one. I’ve never seen my mother do an American thing in my life. Eating every meal with her hands is the only way of life my mother knows. She walks to the beat of her own drum. When it comes down to what matters the most in this lifetime, Serwah Opoku has always known that she can only rely on her intuitions to carry through.

A wave of relief washes over me when I hear the conversation end.

“Bye bye yooo.” Like, we came here for a purpose. Girl, stay focused.

We walk over to the produce stand. Serwah notices how the price per pound of yams went up. She calls for Mr. Jacob, the owner and a dear family friend. They start bargaining back and forth in Twi. As they speak, I try to keep up but I’m not quick at translating. My mother gets her way eventually. I take that as a cue to make my way over to the register, because we do have other places to be. Serwah snaps out of her blissful state, and finally realizes it’s time to move elsewhere.

Next, we head down to the 99 Ranch Market. The smell of fresh seafood swarms around us as I witness my mother dipping back into a state of nostalgia. Here we go again.

Serwah strolls over to the counter. She picks out a couple tilapia and asks for the fish to be cleaned properly. We continue to shop around until the fish is ready for pick-up.

My mother loves frying fish. It’s one of her specialties. I remember afternoons of sizzling oil hitting the pan. She raves about how she used to sit outside back home, just frying fish. There were always polarizing forces trying to block Serwah’s inner peace. The stress of living paycheck to paycheck and taking a second job to make ends meet had nearly sucked the life out of her. Frying fish offered a moment of tranquility amongst all that noise.

Surrounded by a world of intangible realities, my mother wasn’t about to let the typical American diet be imposed upon her. It was already hard enough that she wasn’t able to attain higher education, so she had to settle for working in retail. Once she became a mother, all her other aspirations fell astray.

34 labyrinth

35 spark

RED TOP | Prototype Vintage

GREEN HEELS | Prototype Vintage 37 spark

It was more important to Serwah that her children make something of themselves. She refused to compromise whatever parts of herself she had left for a burger, french fries, hot dogs – any processed food, for that matter. So long as she had God on her side, Serwah could create her own Ghana in America.

This is my mother’s sole mission. By sticking to her traditional patterns she is able to transverse from the intangible into a realm of familiarity — a place providing her safety despite appearing foreign to the white American eye, whose gaze looks at her and tells her to abandon Ghana, to abandon her home, to abandon herself.

Even though I find the smell of seafood nauseating, I don’t mind the place because it gives my mother a dose of serotonin. As they bring out the fish, she smiles wide with her gap teeth. We pay and depart for the India Bazaar — truly a cross-cultural adventure for us today. This place holds a rich essence, similar to that of the Afribbean Market; both of them lack any aspect of whiteness. We listen to Bollywood music play over the speakers while looking for the tea my mother cannot live without.

Every night before my mother left for work, she had me prepare piping hot tea. It was a soothing force, as she would come back in the morning to get ready for her second job. All I wanted to do was make sure Serwah was taken care of, because she’s constantly taking care of everyone else. So long as she carried that tea with her, she would keep pushing through our everyday struggle. It wasn’t anything fancy but two tea bags, mixed with evaporated milk and a splash of honey. She’s been able to conquer homesickness, depression, and worst of all, grief after the passing of her mother & father. My mother is like Superwoman to me, but even superheroes get exhausted sometimes. The heat of the tea forged a strong fire within Serwah’s heart, and I am in awe of how determined she is to keep that fire lit.

Then we step right into Fiesta. Serwah meticulously picks out dozens upon dozens of habanero peppers. A random woman watches as my mother grabs handfuls of peppers.

“What are you planning to do with all of that?” The woman asks.

My mother blankly replies, “Oh, nothing.”

I give a slight chuckle. A woman of my mother’s magnitude prides herself on never revealing secrets. These precious, powerful peppers are sacred to her for their richness in color, flavor, and quality of life.

When I had COVID-19 last year, Serwah had crafted the perfect pepper soup to help me get better. I was taking my medications, of course, but nothing hit the spot like my mother’s home remedy. That soup opened up my airways and cleansed my aura. She finishes bagging up her peppers and heads over to the produce aisle for banana leaves.

“Why are we getting these again?” I ask.

She replies, “Heh, I need it for my banku.”

Personally, I’m not a fan of it, but banku is a traditional dish made of cassava flour. I used to watch Serwah spend hours in the kitchen making it. She used her hands — calloused from working day in and day out — to knead the dough. Then she would divide the dough into smaller sections, and use those dark green banana leaves to wrap it up.

In the end, venturing across town for an entire day is somewhat worth the chase, though I wish she could put a little bit more pep in her step. We visit a couple more places before we finally make it home. The backs of my feet are aching immensely. I’m worn out. I look over to my mother and roll my eyes as she grins from ear to ear. The scavenger hunt fuels my mother’s desire to continue living in a country that feels foreign to her. It gives her the powerful feeling of familiarity, harnessing and protecting her cultural identity as a Ghanaian immigrant living in America. She bargains for goods, has routine conversations in Twi, and makes sure to pick up things of pertinence to her everyday life.

Serwah isn’t fazed at all as she lays down on the couch and says to herself , “ye da Awurade ase. ɛnnɛ ya yɛ adeɛ.”

We thank God. We’ve done well today. ■

38 labyrinth

39 spark

NIKKI SHAH & KATHERINE TANG hmua DAKOTA EVANS & AUDREY HOFF models DANIEL CLENNEY & JOY RICHARDSON

41 spark

42 labyrinth

43 spark

44 labyrinth

by ELLEN DALY

by ELLEN DALY

layout CAROLINE CLARK photographer RACHEL KARLS stylists EILEEN WANG, AVANI SUNKIREDDY & YOUSUF KHAN

layout CAROLINE CLARK photographer RACHEL KARLS stylists EILEEN WANG, AVANI SUNKIREDDY & YOUSUF KHAN

47

hmua LILY CARTAGENA, AVERIE WANG models LAURENCE NGUYỄN-THÁI & MALIABO DIAMBA

spark

My highest highs and lowest lows will always be found on the dance floor.

“It’s Friday night and I’m anxious.”

xhilaration, ecstasy, and communal vision are the gifts of Dionysus, god of wine. Alcohol’s enhancement of direct face-to-face dialogue is precisely what is needed by today’s technologically agile generation, magically interconnected yet strangely isolated by social media.”

— Camille Paglia

— Camille Paglia

Drain the glass by the time you’re done with your makeup. Before you know it, you’re irresistible. Congratulations! You’ve made it from a state of frenzy

to the state of ready. Treat yourself to a cigarette for good behavior.

A few friends arrive and I’m already a few deep. We roll dice, trade cards, perform rituals designed to make us drunker faster. We draw pictures, bounce balls, slap hands and slam spoons. We’re artists, we’re acrobats, we’re athletes, we’re dancers. We willingly get wasted; we don’t believe in danger.

My first weekend in Austin, I found myself in an abandoned-church-turned-rave-location for an impromptu house party hosted by resident stoners

“

LIPS BAG | BIG BERTHA’S PARADISE

and burnouts, kids who’d graduated from the local high school a few years back and hadn’t yet found their way out of town. Nervous and outof-place in my choice SHEIN crop top and white frat Filas, I watched in awe as stick-thin girls in fishnets with facial piercings passed around a bottle of Bacardi and a blunt. I set my intention right there: the party girl, the image of effortless glam, the girl who’s too pretty to give a fuck — that is what I would become.

Two weeks later, I stumble up the stairs at my first-ever co-op party in a drunken search for a bathroom. At this point in time, I have long bleach-blonde hair and my eyes are dusted with glitter and my legs wrapped in fishnets leading up to a zebra print skirt. I feel sexy in my body, and the eyes of the beholder confirm my suspicions. I’m stopped in my tracks.

“Oh my God, you’re, like, a real-life Jules!”

I could’ve cried. The feeling brought on by some random co-op kid comparing me to The party girl I’d been mentally moodboarding since that summer’s release of the hottest new HBO teen drama could be described as nothing less than euphoria. Jules was everything I wanted to be: unapologetic in her style, confident out-of-place at a new school, desired by everyone, stick-fucking-thin.

I’d learned by trial and error in those first few weeks that frat parties were just too aesthetically vapid for me. I needed a party home, an area for the self-expression I pursued in my performance of the party girl, a suitable setting for the character I was building. On a certain September Saturday night, that home was found.

On September 17, 2019, I made a five-song playlist containing “Venus Fly” by Grimes, “disco tits” by Tove Lo, “Vroom Vroom” and “Girls Night Out” by Charli XCX, and “I Don’t Want It At All” by Kim Petras. It was a quick and noncommittal attempt to ideate what songs would play in a dream world where I had the AUX at a party. It was thoughtless and unintentional, a mere concept of a fantasy. On September 21, the DJ at New Guild played precisely those songs, alongside the likes of Nicki Minaj, Troye Sivan, BROCKHAMPTON, Cascada, Fergie, and, of course, Earth, Wind & Fire.

A fire was lit within me. I belonged. I’d embodied the party-girl archetype in a mere matter of weeks and I was rewarded with the DJ set of my dreams. The high of hearing my favorite songs,

ones I’d never imagined I’d hear at a college party, was unlike one I’d ever experienced. It was physical, it was bodily, it was intimate, it was spiritual. It wasn’t just me, either — everyone there was jumping and bumping and singing along. I’d found my people.

I’ve chased that high every weekend since. I’ve found it in mere microdoses at gay clubs, co-op parties, and tunnel raves, but never quite to the extent I did that night at New Guild. I became addicted to the performance of the Party Girl, the girl with enough perceived sexual and social capital to entertain the illusion of power on weekend nights. She’ll entertain any man but never go home with him. She says no to drugs but she never pays for drinks. Her bony body both sexualized and starved of its womanhood, she’s effortlessly cool in a way she used to think only boys could be.

*

Upon arrival at the club, I beeline to the back patio to light a cigarette and kiss the hands of adoring fans. I begin by asking older men for a lighter when I already have my own.

I’m offered rides home, glasses of wine back at hotel rooms, raves that go until 5 A.M., and, occasionally, trips abroad. I wonder what went wrong in these men’s lives, what brought them to be forty or even fifty talking to twenty-year-old girls in clubs. (As a performer, however, I’ll always entertain.) I’m the youngest, blondest, the hottest piece of meat — I’m the it-girl, the cheer captain, I run the regime.

The cigarettes are sobering so I accept the offered drink. I don’t need it but I do. To get through this moment, to blindly hope for better music and release and rebirth. I slurp it down, throw it away, and follow the disco ball back to the dance floor.

51 spark

“Holy fuck, I’m in love — with life.”

53 spark

“I’m eternal, I’m immortal, I’ll never feel pain.”

Holy fuck, I’m in love — with life, with the song they’re playing and the girls I’m dancing with and the fact that I can escape the monotony of the day-to-day to this seemingly illusory purgatory of a place. I scream and I jump and I shake my body and spin. I hold onto my friends because I never do otherwise and I don’t let go of their hands. I’m eternal, I’m immortal, I’ll never feel pain.

By the time I feel like crashing, the Uber’s already on its way.

Mornings are warm, fuzzy, anxiety-inducing, and dizzying, spent sipping coffee and swallowing regret. Memories of the night are painted with equal parts narcissism and euphoria, neurosis and radiance, friendship and fear. A certain remorse must be felt, a shame inflicted by bodily pain.

Brunch with friends followed by hours in bed remedy the curse of the hangover. You remember you’re loved, you remember you’re normal, you remember that if you get one single life to live on this Earth you’re going to spend it finding every way to experience everything and feel too much and meet everyone and love deeply and laugh and dance and scream because one day it’ll all be over. I love movement. I love conversation. I love looking people in the eye and asking questions I wouldn’t be bold enough to ask otherwise. I’m an anxious social butterfly with an insatiable zest for life. For me, and for many, the sweet release of Saturday night just works. It scratches that itch to transcend the ordinary and enter a world of wonder and whimsy, or at least the illusion of one. I know one day I’ll be over it, that I won’t need the sexy outfits or the adrenaline rush or the gossip or the people-watching or the pursuit of the other, but for now, the chaos offered by the club is one I pursue willingly. ■

*

54

labyrinth

55 spark

“equal parts narcissism and euphoria,

neurosis and radiance, friendship and fear.”

56 labyrinth

BLACK LINGERIE DRESS | Prototype Vintage BLUE VELVET SHOES | Prototype Vintage 57 spark

58 labyrinth

layout AVA JIANG photographer ANNAHITA ESCHER stylist SONIA SIDDIQUI & EMILY MARTINEZ hmua ANGELYNN RIVERA & JAYCEE JAMISON models ARLIZ MUNOZ, MELAT WOLDO & ALEX BASSILLIO

59 spark

SILVER HEELS | Protoype Vintage

60 labyrinth

PEARL NECKLACE | Revival Vintage WHITE SILK SHORTS | Flamingos WHITE GARTER | Emily Martinez

WHITE RUFFLED BUTTON TOP | Prototype Vintage

BROWN HEELS | Prototype Vintage

BLACK GARTER BELT | Flamingos

BLACK VELVET BLAZER | Emily Martinez

A laissez-faire attitude guided much of Hefner’s life and work with Playboy. Rules were boring, propriety was stifling, it should be OK to say whatever (and sleep with whomever) you wanted “as long as you weren’t hurting anyone,” and the emergent generation of young American men ought to be intellectual, progressivist, and liberated — just like the gentlemen who subscribed to the Playboy lifestyle. Unlike the cheap stashes of “porno mags” lining the lower shelves of gas station stores, Playboy was sexy, classy, and sophisticated. Right alongside spreads of nude women were incisive op-eds and interviews with the likes of Malcolm X, Stephen King, and Al Pacino. Hefner himself spoke out against segregation often — Black and white Playmates lived together, worked together, were paid the same — and advocated for freedom of speech.

“It was such a lifestyle,” Pamela Anderson once said in an interview with the Los Angeles Times. “Playboy Mansion was like my university. It was full of intellectuals, sex, rock ’n roll, art, all the important stuff.” It was this interweaving of sex rituals — something perceived by Hefner’s preceding generation as shameful, dirty, and forbidden — into a cultural ethos that held its head high in the light of day that ultimately earned Hefner his cultural preeminence as a “sexual liberator” in the ’50s and ’60s. Sex was now something clever people had, enjoyed, and owned up to; and at least as it related to Hefner’s doublesided legacy, the pushing of this needle certainly paints Hefner in his most flattering light.

Unfortunately, all that makes sex desirable, from its midnight phantasmagorias to its uncontrollable ecstasies and agonies, also makes it dangerous. Hefner did perhaps set out to challenge sex culture in the early days of Playboy — an argument can even be made that he succeeded. But he also invited something more monstrous than he knew into his house, and by extension, the new psychosexual culture which he had embedded into the American conscience. The surrealness of sex makes tangible accountability difficult, something Hefner in his later years liberally exploited. Running like a scar along the underbelly of Playboy Mansion’s celebration of sexual freedom was the cycle of abuse that kept the party going: repeated allegations of the sexual assault and even suicides of Playmates first emerged in the ’70s, then were successively disappeared by Hefner’s “cleanup crew.”

Much of the abuse happened in a psychological twilight zone: in the disorienting, drug-addled moments leading up to sex, during the unwilling act of it, and afterwards, when it was all over — when, waking to the cheerful

morning light shining upon the lush acres of Hefner’s estate, it felt like you must have only woken up from a bad, bad dream. Somewhere along the way, Hefner must have realized this truth, too: that you could buy and sell sex at your leisure, or use it to invoke in somebody any primal human emotion you’d like, whether it was love, shame, guilt, or terror, and it would all go more or less unpunished. It was astonishing what could be forgiven and forgotten in the light of day, what little effort was required to keep these sorts of unsightly narratives from rearing their heads in public.

Even today, in a world that is becoming increasingly unrecognizable to our evolutionary faculties, sex has retained a core position in our collective human culture. It proliferates in an otherwise austere cyberspace and enmeshes itself within our sophisticated economies. We need it, we crave it, we would do unspeakable things to get it. There is, after all, a reason why men in power almost always use that power to realize their sexual desires. Sex is the one part of our original humanity we can’t seem to originate from. The need to feel good is simply too strong, too permanent. What ensures our survival, it seems, also ensures our cruelty.

Following Hefner’s death in 2017, more accounts of sexual assault, drug abuse, and underage prostitution within the mansion have come to light. We, of course, condemned the deadman, sold his estate, and quietly seized his assets to split amongst ourselves. Now both the Playboy Mansion and its landlord’s legacy sit shoulder-to-shoulder in our cultural graveyard: emptied out, decaying, another plain-faced relic of the deceitfully fabulous past, cautioning us against a worser nature we all deny we possess. No wonder why we despise sex so much: it runs countercurrent to what makes us different from animals, undermining our seat of power as self-possessed creatures. It shows us the truth about ourselves. And when we say, “Maybe we can learn from this,” it is the little voice that quips, “Or maybe not!”

Make no mistake: Hefner’s refusal to separate reality from the sensual fantasy which his franchise popularized and profited millions off of was only an early omen of our continued participation in the intimacy economy today. We stake everything — morality, connection, control — on only a few brief moments of ecstasy. How, we ask ourselves with disgust, could we have let this happen?

The answer remains the same each time. How could you have not? ■

62 labyrinth

by HAYLE CHEN

INSEARCH OF THE PERPETUALSELF

layout by SAMANTHA FIRMIN

layout by SAMANTHA FIRMIN

63 spark

64

labyrinth

When I arrive home in Combray that winter, my mother offers me the warmth of my childhood home, petites madeleines, and a cup of tea, which at first, I refuse. There’s a weariness set down to the marrow of my bones, a dread that I cannot seem to shake about the promised monotony each new day holds. I ladle a spoonful of tea and break off a morsel of the cake to place in the liquid. I lift the spoon to my lips, and no sooner had the warm liquid, and the crumbs with it, touched my palate… An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, but individual, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. Joy erupts in my soul; mortality no longer befits me, I am interminable. How do I generate it again? I assemble the concoction once more, bringing the spoon to my lips once, twice, thrice. It is in vain. The moment is gone.

For Marcel Proust, dipping a madeleine in tea catalyzed his discovery of involuntary autobiographical memory — a phenomenon that, because of his vivid documentation, is charmingly referred to as a “Proustian moment.” To experience this moment is to have a memory triggered by means of olfaction or gustation, suddenly and unwittingly.

For me, it’s miso soup, lemon scented Pledge and rain soaked pavement on a humid day. Each scent evokes a hyperspecific recollection: my Chinese grandparents shuffling around in the kitchen as I sit in the dining room tracing characters in a workbook, damp hands dutifully scrubbing clean the kitchen table before a summer crawfish bash, and the cadence of a basketball as it bounces on asphalt during fifth grade recess in the springtime. The nostalgia of each memory grips me into a stupor – I startle in bewilderment and then fall, scrape my knees, and continue sprinting, chasing the elation of recalling the sweet purity of adolescence. When the aroma eventually shifts, the poignancy of the memory fades, but the wonder does not. At the behest of a scent, I step through a portal into my past. Memory is a fickle thing. She is prone to flights of fancy, she is unrelenting, she is unearthed in the most peculiar of ways. Sometimes, she is spontaneous. Every memory is made flesh for a fleeting moment until I encounter it unexpectedly again. Briefly, I am infinite. But then, as is human nature, just as we remember, so too do we forget. The bliss of my childhood abates, the memory fades.

So where do the memories that we no longer have go? Do they slowly wane as time passes, a full moon sliced away night after night until it’s but a meager crescent? Perhaps the aging mind overflows from its overabundance of keepsakes, spilling out in waves that drown in the ether. Neuroscience tells us that the details of a memory dim as the brain’s synapses functionally decline with age. Retrieval becomes difficult with advanced maturation and the vibrance of a memory often deteriorates over the course of a lifetime.

It’s easy to regard memory as a series of absolutes, succinct dichotomies that possess positive and negative denotations: possessing good recall or bad recall, good memories or bad memories, having or not having. But involuntary memory subverts this mold: the Proustian moment grants us a memory when

65 spark

66 labyrinth

we are not actively searching for it. Triggered by external sensory experiences, these memories are thought as the body’s nature’s compensation for the decline in voluntary and strategic retrieval that accompanies aging.

To experience and to forget is the fate of man. So what does it mean that what is lost can still be found, even when we don’t know we lost something in the first place? A taste, a smell, a touch, a view, and a sound – they can catalyze a memory, invoking the past and thrusting a forgotten moment into the present. We are a homemaker’s antique hutch, filled to the brim with knick-knacks and valuables; we are a gardener’s bucket with a hairline fracture, slowly losing our stale, tepid water as time passes by.

We have a human tendency to want to endure, to have a life well-lived if only so others will remember us, lest we be omitted from history entirely. We labor in hope of being memorialized, but we rarely consider what memories lie dormant within ourselves. It matters as much that we remember who we are as it does that others remember us. While Proust remembered various moments during his childhood in IlliersCombray the moment the pastry touched

67 spark

his palate, when a beam of sunlight shutters into a dark room exactly right amid the smell of colored pencils and permanent markers, I’m transported back to afternoons sitting on the living room carpet at my cousin’s house, folding paper airplanes in preparation for a flying contest. Each specific appeal to my senses — only emerging in perfect, unreplicable conditions — evokes a moment lost in time profoundly outside my current temporality. My past self lives on in the present, my present self pulls forth the past.

We often think what is forgotten is forever lost, but in the spaces we inhabit, the people we touch, and the feelings we have, we leave remnants of ourselves – and we keep some as well.

A Proustian moment is a gift, an offering at the altar that is our mind, presented by our childhood selves. Memories are prioritized, filed and stored and retrieved when necessity dictates that remembering a certain action, event, or experience would aid in survival. Our mind delineates: shortterm, long-term, suppressed. But what is forgotten can be rebirthed. We can recover a poignant memory because,

in essence, it is never truly lost. The senses transcend ephemerality; the mind is elastic. I am not mediocre, accidental, or mortal. Layers upon layers of myself exist, are hidden and may be unearthed and cherished as long as they last. Perpetuity exists. She is inaccessible, she is elusive, she does not heed the commands of Routine and Structure. She exists; she lives in the self.

Rich miso, the sharp citrus of Pledge, a sidewalk drenched after a thunderstorm. My childhood comes flooding back. ■

“Perpetuity exists. She is inaccessible, she is elusive, she does not heed the commands of Routine and Structure. She exists; she lives in the self.”

layout MAYA NGUYEN photographer REN BREACH stylists VIVIAN MOYERS & EMILY MARTINEZ set designer CAROLINE ST. CLERGY hmua IRINA GRIFFIN model MALIABO DIAMBA

layout MAYA NGUYEN photographer REN BREACH stylists VIVIAN MOYERS & EMILY MARTINEZ set designer CAROLINE ST. CLERGY hmua IRINA GRIFFIN model MALIABO DIAMBA

70 labyrinth

LACE BUSTIER | Prototype Vintage PINK EARRINGS | Flamingos PINK NECKLACE | Flamingos

71 spark

72

labyrinth

73 spark

74 labyrinth

environment COLIN CANTWELL

EGODRUNK // SOJOURN ON SIXTH // FANGIRL // A DREAM OF ONE’S OWN // A BAD FAITH REALITY // MATERIAL VOID // THE MOUTH OF THE DESERT // STAR-SPANGLED FUGUE // M+ // SACRED SKIN

R.E.M.

SOMETHING ISN’T RIGHT HERE. STRANGE FIGURES APPEAR IN THE MIND’S PERIPHERY, EERIE AND TRANSIENT, LIKE GHOSTS. THAT GLEAMING DOOR YOU REMEMBER STEPPING THROUGH SEEMS TO HAVE DISAPPEARED INTO THIN AIR, BUT THE AIR IS MOVING, YOU CAN SEE IT, IN STRANGE SWIRLS AND TWISTS. IS THIS WHAT YOU EXPECTED? YOU CAN’T REALLY REMEMBER.

GATE TWO

76 labyrinth

by MILES NGUYEN

by MILES NGUYEN

77

layout CARO ARREDONDO creative director REN BREACH photographer REN BREACH stylist MADDIE JEWESSON & SATURN ECLAIR TEJADA set designer TYLER KUBECKA hmua JAYCEE JAMISON model LEILANI CABELLO

spark

Show me your hands — their skin, their shape. Would you believe me if I told you there are things they could not dream to hold?

78 labyrinth

Look at me! Slipping through this gate just in time to hear the night begin her well-deserved bout of laughter.

And here I am — unlaced and nauseous-sweet — and I can be nothing but drunk tonight.

Come, come! cut me open, you will see — I am a genius and bigger than any cup you could pour me into for liquid is always the sufficient mode and eye-for-an-eye is the perfect vow.

“and eye-for-an-eye is the perfect vow.”

I can admit that I am not above being crazy visible from time to time — but even so I am far far too famous to stand being recognized in moments like these. Instead, I will use whatever sharp things are in my mouth and tear open this senescent state this regurgitation.

80 labyrinth

O — did you know? that survival depends only on being gorgeous gorgeous gorgeous Well lucky me, I am just that — swan-necked and spinning so fast I become a circle stopping only for mirrorlooking.

81 spark

“stopping only for mirrorlooking.”

82 labyrinth

83 spark

Now see: The wicked nurse has come to stitch me back together leaving me with nothing but a small stone — a pity gift, poor imitation of moon. By high morning I will be wrecked and rolling it between my fingers hoping it will loosen up my chest or rearrange me into an apple or a seed. ■

84 labyrinth

85 spark

86 labyrinth

t must have been 8 in the morning when I opened my eyes to a sickening sensation — to an ax which had split my brain in half.

I looked around at the dimly lit room and at the dull walls painted a beige hue. I looked at the clothes lying all over the floor — those skin suits I already resented wearing now that I must clean them. Perhaps if I threw myself in the washing machine with them, I would forget.

I would forget about the migraine, about the foul smells emanating from my trash can. I would forget about that stranger’s text, about the two Advils I would have to swallow, and about the apologies I will have to make. I would forget about —

the joy I felt.

I looked down at my body, at the suit clinging onto my back, as I remembered the girl I was the night before. She bared more skin than usual, exposing a saccharine surface from someone’s spilled cocktail, on which the shimmers of a mandarin-scented body lotion danced around beads of sweat. I regretted having to peel it off, despite how foreign it now felt on me. But at the same time, I wanted to cover up and cry myself back to sleep. I wanted the suit that made me carefree to be acceptable to me in the daylight.

I liked that the drunk me did not care about speaking a little too loudly, smiling a little too widely, and dancing a little too disorderly. I liked that she forgot about tucking her stomach in and rolling her shoulders back. I liked how easily she opened up to others, and how she was bold enough to say the wrong things. I liked how unafraid she was to fall because she knew she could count on herself to pick up the pieces. I liked that she could be me if I were willing to look at myself a little differently.

Alcohol’s most enticing feature is the possibility of abandoning one’s responsibilities. In a way, drink-

ing is the ultimate liberation. Who would pass up on that?

I used to believe that drinking alcohol was submitting to a different set of rules; it was giving into peer pressure and betraying your morals for social acceptance in its shallowest form. Why should I dance and pretend to be friends with people who do not know who I am — who will act like I wasn’t there the next day? I did not believe that I could be myself if I lacked awareness.

For the entirety of my high school years, I did not have a single alcoholic beverage. I felt great discomfort with the idea of forfeiting self-control for an ephemeral taste of freedom. I convinced myself that I could have just as much fun as anybody else in the club. All I had to do was sway my body to the rhythm of the godless crowd and submit to the midnight sky. All I had to do was pretend that nobody was watching me — not even from the heavens — because no one was.

But I grew up and realized that I was no longer capable of releasing my inhibitions and letting loose for the night. Imagining my body and the space it took in the room, dancing and having fun and being happy, horrified me to the point of denying myself these simple pleasures. I became increasingly ashamed and felt it necessary to become quiet and disappear. During the rare evenings when I would go out, alcohol became my remedy.

Growing up was believing I could no longer refuse that shot of tequila. It was far easier to relinquish my better judgment for the sweet sip of deliverance, ignoring its bitter aftertaste, than to flirt with the fact that I did not like myself. The first time I got even remotely tipsy occurred during my second year of college. That night was the most fun I had in a long time. For a $12 shot, I could pretend everyone around me had vanished and I was dancing on the pink rug of my childhood bedroom once more.

Drinking is a slippery slope. When I recognized how good I felt, there was no such thing as one drink too many. The first drink was always the most dangerous: it dissolved my initial reserve and lulled me into a state of false safety. When I believed drinking was the closest I could get to being

88 labyrinth

89 spark

myself, I didn’t quite understand the shame. If I was having fun, why was I embarrassed the next day? Although there exists a carefree version of myself buried within me, I am not whole without my rationality, earnestness, and calm. Rather than embrace the carefree lifestyle, I merely became a caricature of the “party girl.” While there is nothing wrong with her, she is not who I am. Drinking is the kind of liberation that allows me to forget myself rather than

embrace myself.

Then came another wave of sensations: migraines, nausea, partial amnesia, and aches all over my body. My limbs scolded me for my thoughtlessness. What were you thinking? You have class at 9 a.m.! The worst feeling of all was regret. Drinking made me feel comfortable in my body by harming it on the inside. I could not keep gambling away my tomorrows for a shot at a perfect night. I needed to learn how to tune out the self-inflicted noise on my own rather than resort to this deafening medicine.

Though I haven’t taken a vow of sobriety, identifying why I was drawn to alcohol and what I liked about myself when inebriated have taught me control. I will allow myself a drink or two of alcoholic beverages I actually enjoy and let the mood seduce me for the evening. It has been a potentially lifesaving compromise. I can learn to feel natural in unexpected places but I can also remember —

the joy I felt.

I never needed a brand-new suit. I simply needed to decide how I wanted to wear the one I already had. So, I slipped on my party skin suit and went back to the club, not necessarily as a changed person but as one who was changing. Feeling slightly buzzed with warmth spreading across my cheeks, I waited patiently in line and quietly hummed the tune of the music blaring inside. I remember the remainder of my night: dancing and jumping around, trying to sing the lyrics of songs I did not know and talking to people I would have never approached otherwise. When the street itself decided to call it a night, I took an Uber home with a smile tugging at my lips the entire way back. ■

90 labyrinth

91 spark

93 spark

94

labyrinth

M+ M+ M

by EUNICE BAO

UNDERGROUND ART IN RED HONG KONG.

by EUNICE BAO

UNDERGROUND ART IN RED HONG KONG.

M+

layout MELANIE HUYNH

layout MELANIE HUYNH

It was an abnormally bright day when we took the C1 exit at the Kowloon Station in Hong Kong. Following signs to the M+ museum, we walked down Nga Cheung Road, a thin sidewalk next to concave land and construction lifts. We didn’t talk much, just squinted, at the blinding light of the towering apartment buildings, all twisted and turned like a rubik’s cube. I told my friend that it felt like we were entering the Capitol in the Hunger Games, only, well, we were going to see art.

You could tell West Kowloon Cultural District was new. Besides the orangesuited construction workers, pedestrians were all museum-goers clad in typical Hong Kong fashion: platform shoes, solid silhouettes, and draped fabric. The district started building its foundation nearly a decade ago, on artificial land filled with thin earth. Urban designers layered the museum atop the Airport Express railway tunnel — which would take you into mainland China, though that gate has been closed for the past two years due to the pandemic.

The M+ museum opened in 2021 as Asia’s first global museum of virtual culture, boasting 700,000 square feet with 8,000 works of contemporary Asian Art. Jacques Herzog of Swiss architectural firm Herzog and de Meuron describes the M+ project as literally “emerging from the city’s underground.” For art to enter a city “like Hong Kong,” he says, it must come from

“below.”

And what of a city “like Hong Kong”? Perhaps most directly, Herzog was referring to a city lost in transition, with so precarious a sociopolitical position it could collapse any second. Torn between British colonialism and its motherland, Hong Kong has endured decades of identity crises. The political maxim, ‘One Country, Two Systems,’ at first promised a semi-autonomous status apart from mainland China, including freedom of speech and artistic expression. As China became more powerful through its increasingly capitalist economy, though, this promise began to fracture.

When the M+ museum opened, Beijing’s iron wall of censorship fell upon them, imposing a national security law in response to brewing local protests. This means, displayed art cannot be blatantly counterrevolutionary. Soon enough, the museum censored artist Ai Weiwei’s Study of Perspective, which pictured him raising a middle finger in front of significant institutions such as the Tiananmen Square. Local and global criticism followed, because how does art exist without freedom?

Freedom of speech is a Western ideal, yet its influence runs deep in China. Chinese university students famously raised their own “Goddess of Democracy,” modeled after the Statue of Liberty, during the pro-democracy protests of 1989. It stood 33 feet tall in the center of Tiananmen Square until the Communist Party’s army destroyed it when they stormed the square in the dead of night. We don’t know how many were killed, anywhere from hundreds to thousands. To this day, the Chinese government fails to address it.

Walking around M+ in my now last year of college, I came across a photograph of a man lying down in Tiananmen Square in subzero conditions. The label said he remained for 40 minutes until the condensation from his breath formed a thin layer of ice (Song Dong, Breathing, 1996). Unlike Ai Weiwei’s middle finger, Song Dong’s commentary was subtle, as fleeting as the click of his camera. As I hovered over the photograph, I began to understand that subtlety was not just a form of artistic expression; it was the only medium for any artwork that exposed China’s past. Lying on the ground, the artist reminded me of the sense of helplessness that permeated Beijing the summer of ‘89. My dad conveyed this much to me when he would vaguely speak of China’s dark history, and what propelled him to move us to the US not soon after.

97 spark

I remember taking a photo in Tiananmen Square some time before we left Beijing. I was nine, and my mom handed us mini Chinese flags. My mom said I looked “too serious,” so I smiled and waved and chewed a bit on the plastic straw holding up the flag. In the background, Mao sported his infamous soft smile in his portrait at the center of the building. I felt uncomfortable with the godhood of Mao, but could never pinpoint why. I was young and naive, with a family who — like many other Chinese families — didn’t talk much about our ancestry.

One of M+’s many Mao exhibits showcased a Mao suit from Vivienne Tam’s Spring/Summer 1995 collection. The fabric consisted of a checkerboard of black and white Mao portraits, alternating with Xray filters of him. It wasn’t my first time seeing Vivienne Tam’s work — us young creatives liked to call it “camp,” a word referring to anything exaggerated or amusing in an unexpected way, largely optimized by trendy fashion pieces.

There was something different about seeing it here, though, as the Mao suit stood awkwardly next to a collage of propaganda from the Cultural Revolution. Such slogans were once plastered on every school and building in China: Closely follow the great leader Chairman Mao…, all must think of Chairman Mao, all must obey Chairman Mao… All around, the exhibit had traditional depictions of Mao as the rising sun and more of Mao with pink lipstick from contemporary Chinese artists. It became evident to me then, how Mao was once, and still is, an object of worship, and how art made him less of a god. The word “camp” took on a deeper, subtler, more urgent meaning.

As the sun set, a pool of people piled in front of the

third floor to take photos of the golden construction site outside, as if it were part of the museum. It seemed to be showing the promising new Hong Kong, atop its modernized land and fancy Swiss architecture. To the right of the window, another group gathered to watch a film projection — Seven Sins: 7 performances during the 1989 China/Avant-Garde exhibition. The exhibition immediately shut down when artist Xiao Lu fired a gun in protest during her installation, and the film looped back to the beginning with no further commentary. The parallel of these two groups showed the obvious — the museum lived in a contradiction of its past and future, modernization and tradition. Exiled artist Kacey Wong called M+ “a museum with part of its hands tied behind its back,” especially compared to the artistic variety of other premier art institutions like the MOMA or the Tate Modern. Like Hong Kong, the M+ museum’s existence is precarious.

And yet, it stands in West Kowloon. I found freedom the day I visited, in a way I haven’t been able to. I don’t think we can demand democracy in art when there is little in its country. It was enough for now to know that art survived in a culture set on erasing its past, that the exhibitions in M+ revealed a bit of forgotten history and answered questions I was too afraid to ask my parents.

When my friends and I left the museum, we walked outside to the Kowloon District’s promenade. Colors from the M+ Facade, a huge screen that overlooked Victoria Harbor, lit up our faces, its watery LED stripes reaching towards something. ■

98 labyrinth

inherited my love of The Beatles from my mother, who regularly played their compilation album 1 when I was younger. I think they wrote beautiful, compelling songs about love and loss that transcend space and time. They’ve even soundtracked many critical phases of my life. We’ve taken Beatles-themed tours of London and Liverpool, and we collect kitschy memorabilia. We’re definitely fans.

In January, I drove home to Shreveport so my mother and I could attend a show by a tribute band called Liverpool Legends. I learned they were hand-picked by George Harrison’s sister Louise to honor her brother, which meant they had to be good, but I didn’t expect the startlingly uncanny resemblances their physical appearances and voices held to those of the actual band. I surprised myself by sobbing and even screaming, especially when the George impersonator played the famed guitar solo in “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.”

Part of the show’s set design was a projection of video clips I recognized as footage of Beatlemania. The clips were black and white scenes of total madness, colored by uninhibited desperation not entirely sure of what it desired. Girls and women waiting outside venues and hotels screamed, sobbed, and fainted, bewildering security personnel and the media.

“This is Beatleland, formerly known as Britain, where an epidemic named Beatlemania has taken over the teenage population,” a newscaster in one of the clips said.

Watching the girls, I wanted to scream, too. In my teenage years, I could’ve been one of them. I’m confident I would’ve been hopelessly sick with Beatlemania in the 60s. I understand why they screamed. I know fangirling doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

In its disastrous wake, World War II left a fractured geopolitical scheme. The psychological trauma of the war, the apocalyptic power of the atom bomb, and the desperation of capitalists, colonizers, and imperialists to maintain their hegemony infused the world, particularly the West, with a deeply entrenched paranoia. In Britain and America, the 1950s introduced the teenager as a social category. British youth navigated conservative culture, economic anxiety, and fear of an arms race. In America, those in power produced a culture defined by hypernationalism, conservative and traditional values, and the nuclear family. With their long hair and soft facial features, The Beatles represented the possibility of rejecting conformity, embracing joy, and living an authentic life.

Within two years of their formation, the band left behind their working class neighborhoods in Liverpool to embrace nationwide fame. A year later, Beatlemania reached America, and 73 million people tuned into their 1964 performance on The Ed Sullivan Show. When asked what he thought about American fans, John Lennon responded, “They’re the wildest.” During their 1965 concert at New York’s Shea Stadium, the band couldn’t hear themselves perform over the cacophony of screams.

At first, this is what they wanted — knowing that fangirls are fueled by the glimmer of hope that their favorite might notice them someday, The Beatles directly addressed their young female audience with songs like “Love Me Do” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” Fame and attention quickly exhausted them, though. Most mortals (un)fortunate enough to taste deification cannot withstand its weight. Within six years, The Beatles had become global superstars on a scale no one could have warned them about—because they were the first. Partly due to fear for their own safety, the band made the decision to stop touring for good.

101 spark

102 labyrinth

Male writers, psychologists, and political analysts held female Beatlemaniacs in pejorative contempt. To them, these girls were crazy, dull, useless, stupid failures. I think these critics feared unbridled feminine emotion, and I think some of them were just jealous. I also believe American Studies professor Allison McCracken’s theory that fangirls are positioned at odds with white male masculinity, the kind that demands emotions always be kept in check, controlled, and stifled. She believes their emotional excess represents an association with those on the margins of society, including working-class people, people of color, and of course, teenage girls.

The Beatles’ young female fans became the architects of their own dreamlands that would free them from the strangulation of the cultural repression that demanded their docility and their dullness. Their screams, tears, fainting spells, and energetic heartbeats were a collective performance of somatic resistance to social control.

The stereotypical fangirl is a female teenager with a wall full of posters of her favorite boy bands and male pop stars. Back in the 60s, she waited for The Beatles outside venues and hotels, screaming and crying, holding a hand-painted sign proclaiming her love. She always had the radio on and tuned into every television performance, if she wasn’t able to be there in person (if she wasn’t able to be there in person, standing for hours in a mile-lone queue). She was Jan Myers, who on an October day 1965 descended into the sewers of northwest London with the objective of crawling her way under Abbey Road Studios, where The Beatles were recording their last album Rubber Soul. A couple years prior, Jan had skipped school to ride her bike 20 miles to Heathrow Airport so she could personally welcome the band home to England.

In the twenty-first century, the stereotypical fangirl isn’t too different from her ancestor, but she has the Internet, which altered temporality forever and awarded her the illusion of constant access to her favorite. The fangirl

“THEIR SCREAMS, TEARS, FAINTING SPELLS, AND ENERGETIC HEARTBEATS WERE A COLLECTIVE PERFORMANCE OF SOMATIC RESISTANCE TO SOCIAL CONTROL.”

104 labyrinth

105 spark

NOT OUR FEMINIST FIGURE. NOT OUR SURREALIST ICON.

by ANJALI KRISHNA

layout CAMILLE CHUDUC photographer CEASER stylists ISABEL SITAR & SUMMER SWEERIS hmua ANGELYNN RIVERA & ADREANNA ALVAREZ models ARLIZ MUÑOZ & NATAN MURILLO

by ANJALI KRISHNA

layout CAMILLE CHUDUC photographer CEASER stylists ISABEL SITAR & SUMMER SWEERIS hmua ANGELYNN RIVERA & ADREANNA ALVAREZ models ARLIZ MUÑOZ & NATAN MURILLO

107 spark

108

labyrinth

The sky is painted a wet, rainy gold on the day Frida Kahlo is impaled with a handrail. A streetcar, at full speed, slams into the bus she’s riding. Frida doesn’t immediately know to balk at the piece of iron shooting through her pelvis and spine; its severity doesn’t seem remarkable. She doesn’t even realize she is wounded until a bystander attempts to pull it from her. Her screams are so loud she drowns out the ambulance’s siren.

The accident leads her to a desert wasteland where her body matches the landscape. She paints “La Columna Rota” almost 20 years later, and she is the titular broken column. A pillar of the ionic order shoots through her center, holding her up but tearing her apart. Nails decorate her, reaching to embellish what is unbroken by bloody wounds. Frida thinks herself Jesus Christ nailed to the cross, or St. Sebastian, shot with arrows for his faith: she’s a saint, a martyr, holy in her pain. She cries, yet stares down her viewer with knowing eyes, asking them to acknowledge her hurt and revere her for living through it. At just 18 years old, she has deemed herself an immortal sufferer, a Sisyphus to be worshiped.

Though she wishes she were well, she won’t let go of her injury, if only for the sake of her art. She is no goddess to pray to. Frida is just a person: a person with a debilitating injury and a paintbrush who chooses all the wrong things and copes in all the wrong ways. When tragedy crawls to her, she delves deeper into it. The battle in her blood cells, between sickness and health, inspires her. It consumes her. It becomes her.

Of 143 marvelous paintings, 55 are self-portraits. Frida found her best subject in herself – the tragedies that devastated her and the loneliness that engulfed her served as abundant material for her work. Her reality informs her art: vivid colors and organic lines, monsters and magic, creatures and folk tales. The supernatural, to her, is part of the real world. Only through a sensual, magical realism is Frida able to de-

“SHE REVERES HERSELF FOR TREKKING THROUGH HER HURT, FOR MASTERFUL PAINTING AGAINST ALL ODDS.”

pict to the average viewer her daily reality. The stuff of others’ nightmares is now her truth, and it makes her absurdity in art all the more heart-rending. Or, at least it’s supposed to. She reveres herself for trekking through her hurt, for masterful painting against all odds. Through her work, she invites our pity. It becomes her oxygen. She lives from it.

But Frida has always been drawn to destruction. She meets her future husband, Diego Rivera, at 15 — precocious beyond her means, shamelessly flirtatious with a man of 37 in front of his jealous wife. She sits for hours and watches him paint a mural at her school. In the way of young girls, Frida whispers to her friend that she will one day be his wife.

They’ll meet again years later, after her accident. When they do, her lifelong obsession begins:

Diego = my husband / Diego = my friend / Diego = my mother / Diego = my father / Diego = my son / Diego = me / Diego = Universe.

She’s nervous the first time she brings Diego to her childhood home, “La Casa Azul.” She must be; he’s 20 years older and a known cheater. She can picture Diego well in her veranda, among tchotchkes from Mexican folk stories, the brightly colored objects of her country that would inspire her half-human/halfanimal notebook sketches and the monsters on her canvas. She can see him wooing his mother with his national pride. But she can’t exactly picture Diego with her father, with his German-accented Spanish, or in front of La Casa Azul’s French facade.

The dinner (or lunch, or afternoon tea) goes badly. Her parents are upset, and Frida has seen him glance at her sister one too many times. Still, they wed: “The Elephant and The Dove,” her father calls them. Her childhood home never houses them together. They live separately through both of their marriages and Frida bleeds for him in red brushstrokes.

Diego is nothing but canvas and oil, but he is her third eye: part of her, essential. “Diego and I” shows her heartbroken with her notorious womanizer of a husband. Her own hair, rarely so wild and loose, lines her neck as if to strangle. She cuts it all off after finding him in bed with her sister.

Diego and her are as cursed as Frida paints them to be — otherworldly, pagan, and everything to each other. In their wrongness, she revels: painting after painting, “Diego on my mind,” obsessive love letters hidden in her diary, animals adopted as surrogate children. Frida finds herself infatuated with her own

110 labyrinth

EMBROIDERED HEARTS | Klein Designs RED DRESS | Flamingos

111 spark

SHOE COVERS | Summer Sweeris WHITE PANTS | Isabel Sitar GOLD SUN EARRINGS | Klein Designs

OWN SELF IS THE ART—WROUGHT BY TRAGEDY, SHAPED

suffering. Her and Diego’s tumultuousness doesn’t deter her from continuing their relationship; it encourages her. She remains with him for years in their own twisted form of love.

As much as her heart breaks, she’ll cheat too. She’s nothing to look up to, this Frida. She sleeps with Leon Trotsky, whom Diego brought into his house for safety from extradition near the end of their marriage. She obsesses over Joseph Stalin, painting “Stalin and I” after his several thousand murders are revealed. She writes about the men and women she loves next to “mi Diego” in her diary. Her independence fell in the face of romanticization, at men of power and creativity. Her character faltered when it came to her idols.

She wakes one morning and across from her in bed is herself. “The Two Fridas,” she whispers, two mirror images of herself, as different as they are replicas. A thin vein wraps around two versions of herself, connecting European Frida, who is trying to stanch the bleeding of her torn heart, to Mexican Frida, who is in traditional Tehuana dress and holding a photo of Diego. Both are somber, but only Mexican Frida is healed. She is who Diego wants: a fellow Mexican muralist, a good woman with a sensible mind and healthy creativity. European Frida holds forceps to clamp her vein, but blood still spoils her clean white dress and their marital bed.

She’s neither and she’s both, torn between her worlds: Mexican or not, Diego’s or not, healthy or not. She’s somewhere in between.The Two Fridas join hands, but still, she bleeds.

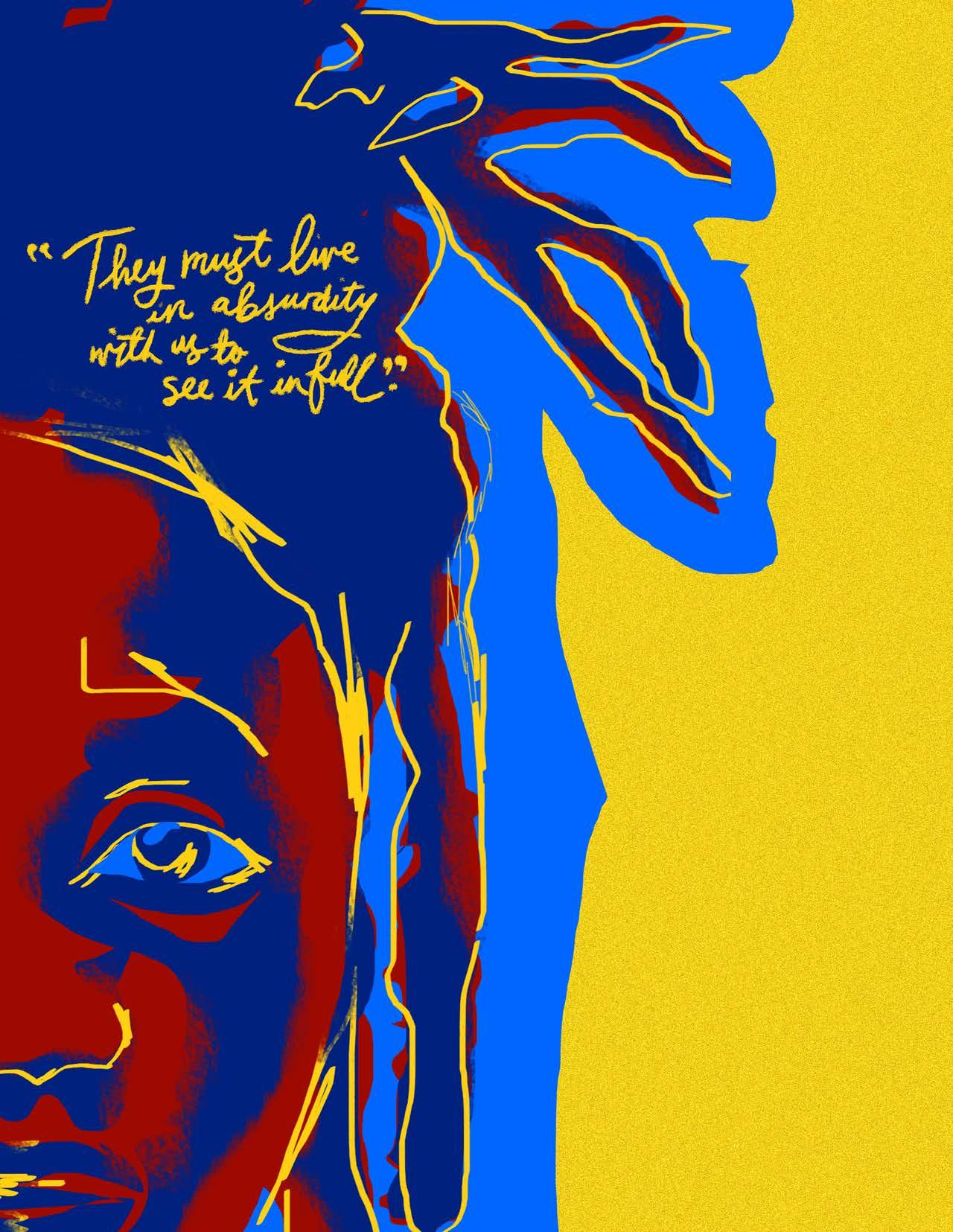

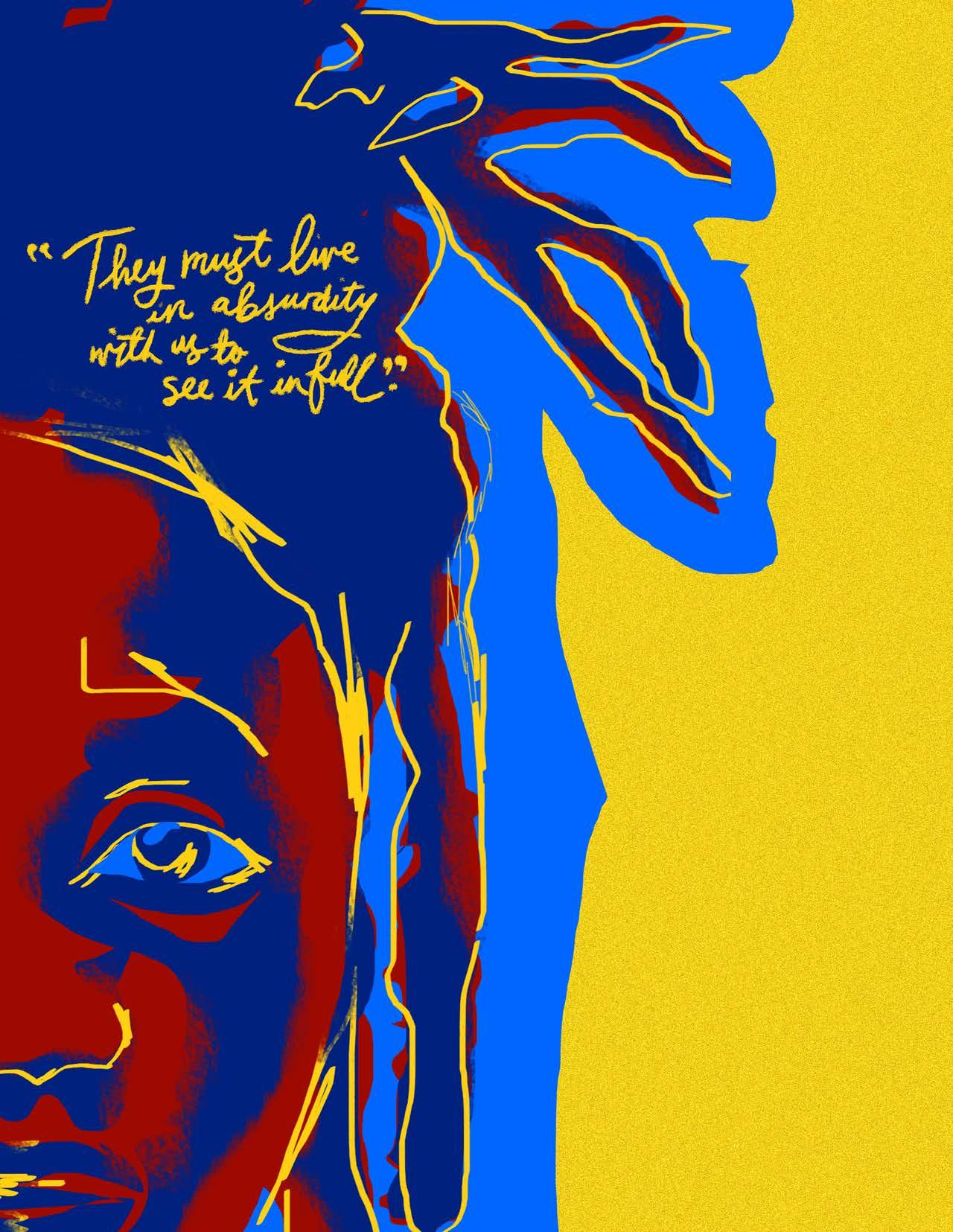

In her storied life, there is no perfect Mexican artist or American capitalist icon. There is no broken body or healthy figure. There is no feminist symbol or “wife of Diego Rivera.” She is a study in duality, a question of faith. Frida’s own self is the art—wrought by tragedy, shaped by injury, and finally, encased in paint. She is devastated, so she turns to art instead, painting as a catharsis just as the Surrealists did. But she was never interested in being part of their movement. She painted from her life, not dreams and latent feelings in these dreams as the Surrealist title would have suggested. She’s a deer shot to death in the woods, a mangled body held up by a column, thorns piercing into her neck. Her monsters don’t remain on canvas or come from her unconscious: they lie with her in hospital bed and home.

Her words are cruel, crude. She knows she is selfish, she knows she is unkind, and still, she is an artist. She sits, holding hands, staring into your soul. She bleeds, yet stares. She looks at you, however, and sees herself. She sees Diego, she sees Mexico. She sees dreams, and nightmares, and she’s haunted by the fact that this is all, somehow, while she’s awake. ■

“FRIDA’S

112 labyrinth

BY INJURY, AND FINALLY, ENCASED IN PAINT.”

by GABRIELLE IZU layout SRIYA KATANGURU

Almost everything in life is socially constructed, including race.

But, as we ’ re stuck with it, we may need to rethink the wayweconceptualize the “race problem.”