The Bitter End Not Just for Snowbirds

By Captain J. Gary "Gator" Hill

I

t’s that time of year again, time for the annual snowbird migration. Not just coots and loons of the winged variety, but the boating variety as well. Each fall we start seeing these boaters flee the northern climes, headed on a southerly course. An early indication is increased chatter on channel 16, sometimes entire conversations. (Please remember this is a hailing and distress channel!) But I say that with a smile on my face as many of us envy their lifestyle and hope we, too, can one day join the flock. Some make this journey in long jumps on the “outside,” while others make their passage using the “ditch,” properly known as the Intracoastal Waterway, or ICW for short. However, the ICW is not just for Snowbirds; many locals along its three thousandodd miles of connecting waterways use these waters for fishing, skiing, and other forms of pleasure boating. The main reason for the ICW’s existence was as a much needed easy route for commerce within and between coastal states. It was originally planned as one large circuit of the eastern and southern coasts, but the connecting portion called the Cross Florida Barge Canal was never completed due to environmental concerns. So today it is broken into the Atlantic section and the Gulf Coast section, or the GICW. But let’s slow our roll just a second. This idea isn’t, or wasn’t, a new idea. The seed was planted way back in the late 1700s, not long after we became a nation, and then again in 1808 by Treasury Secretary Robert Gallatin. Though the needed 20 million in funding didn’t occur then, the advent of the War of 1812 opened our eyes to the need of such a thoroughfare and the 1824 General Surveys Act placed this into the purveyance of the Army Corps of Engineers. Connecting four major projects on the east coast it was slow coming to fruition, considering after the Civil War monies were being diverted to railway commerce. Even though the railways received the funding they couldn’t handle the demand, which became apparent in the 1906 harvests. Federally mandated, the control depth of the ICW is 10-12 feet, and for many years that wasn’t an issue. Tugs and barges using the waterway were moving tens of millions in commerce annually. However, the decline of this commerce has seen the ICW falling into disrepair with many areas now only passable during high tides. One such place is between Ossabaw Sound and St. Catherine’s Sound, aptly named Hells Gate (Hell Gate on NOAA charts). Folks, when you see something named like this on a chart, take it as a warning: it’s not likely going to be rainbows and unicorns. I’ve been sailing these waters since the early 2000s both recreationally and professionally. I remember heading south with our race boat with a six-foot draft and trying to time it with the tide even back then. Today’s charts have this dangerous section listed as a shoaling area.

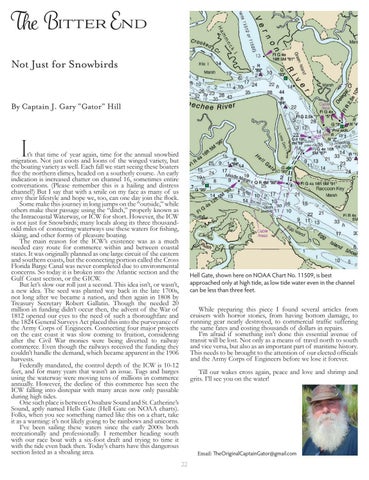

Hell Gate, shown here on NOAA Chart No. 11509, is best approached only at high tide, as low tide water even in the channel can be less than three feet.

While preparing this piece I found several articles from cruisers with horror stories, from having bottom damage, to running gear nearly destroyed, to commercial traffic suffering the same fates and costing thousands of dollars in repairs. I’m afraid if something isn’t done this essential avenue of transit will be lost. Not only as a means of travel north to south and vice versa, but also as an important part of maritime history. This needs to be brought to the attention of our elected officials and the Army Corps of Engineers before we lose it forever. Till our wakes cross again, peace and love and shrimp and grits. I’ll see you on the water!

Email: TheOriginalCaptainGator@gmail.com 22