Debbie August collects to marry

By James Haldane

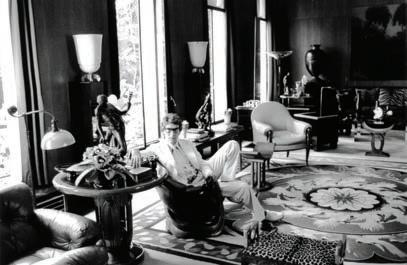

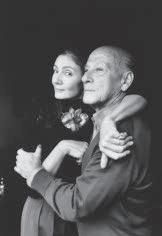

Where does the desire

collect one

Above: A 1994 photo of Paloma Picasso seated in a circa 1920 Armand-Albert Rateau chair at the home of Yves Saint Laurent, also pictured. Right: A unique “Choupatte” sculpture by Claude Lalanne, one of many works by the artist to be offered in the auctions of collector Pauline Karpidas, photographed by Barney Hindle. Below: Al Ain Oasis in Abu Dhabi, home to over 147,000 date palms, nourished by a 3,000-yearold falaj irrigation system, photographed by Natalie Lines.

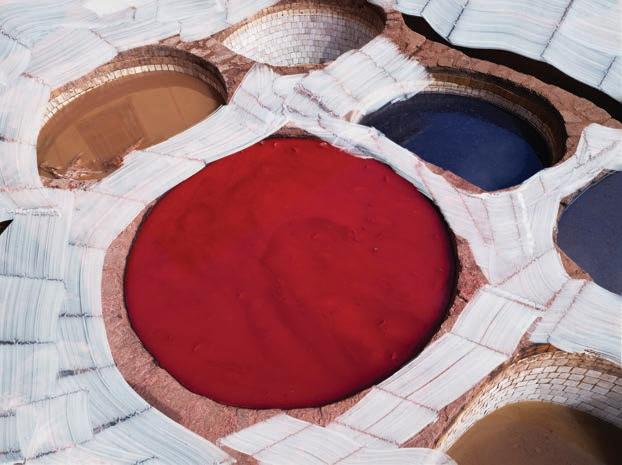

Morocco’s centuries-old dyeing techniques ignite a bold,

Fashion designer Nili Lotan makes an inspired

The standouts from the latest high jewelry collections exude an easy elegance.

By Frank Everett

Photography by David Abrahams

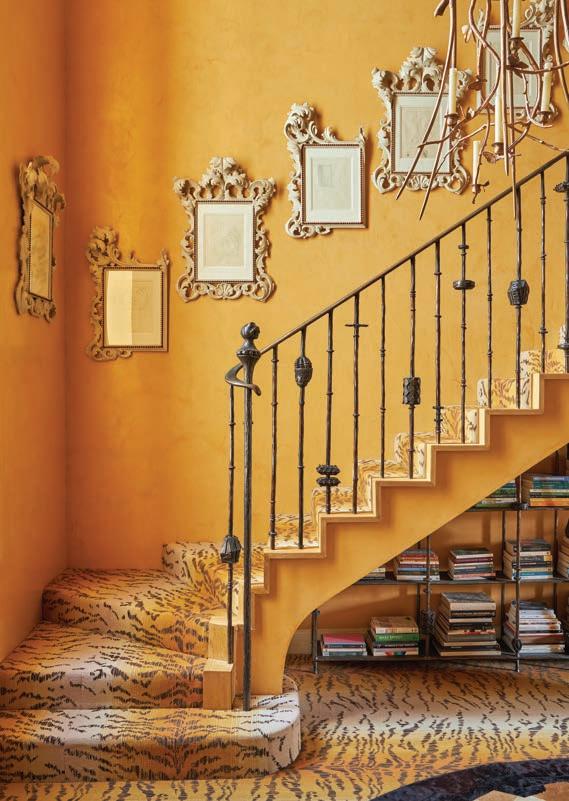

110 A PATRON IN RESIDENCE

The London apartment of Pauline Karpidas holds a singular collection of surrealist icons and 20thcentury masterworks.

By James Haldane

Photography by Barney Hindle

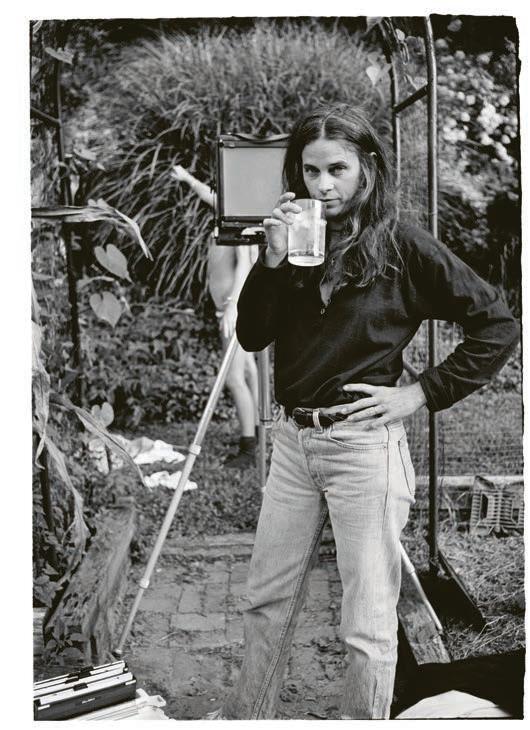

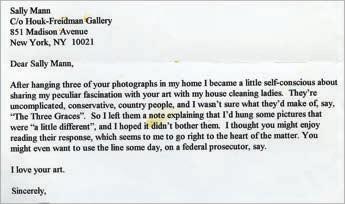

116 FROM SALLY MANN’S PERSPECTIVE

In an excerpt from her new book, the photographer discusses implications of censorship on her career, family and life.

By Sally Mann

120 THE PRIZE IS RIGHT

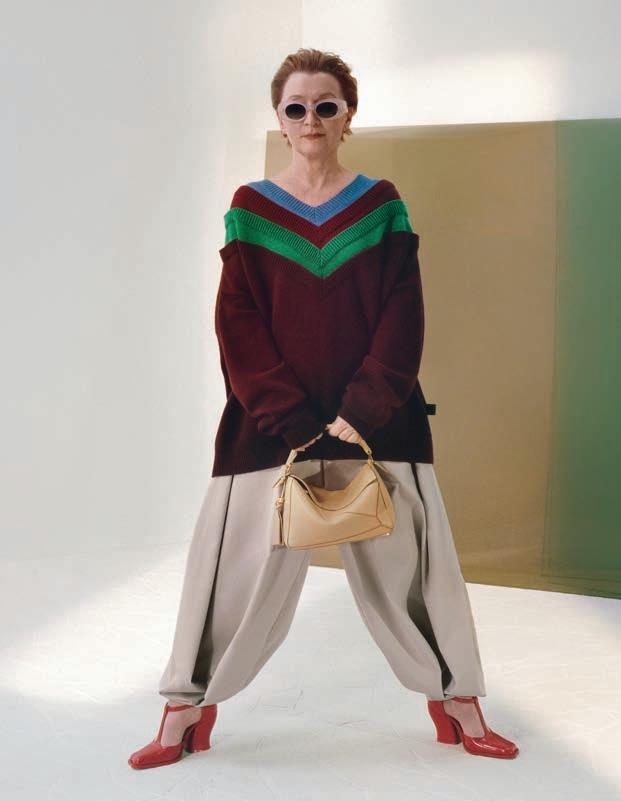

With its Craft Prize, the Loewe Foundation is bringing serious acclaim to undersung talent.

By Joshua Levine

128 ABU DHABI RISING

Past and future intersect where burning sands, hazy skies and turquoise tides set the scene for some of the world’s most ambitious architectural endeavors.

By Amanda Randone

Photography by Natalie Lines

144 HISTORY TAKES FLIGHT

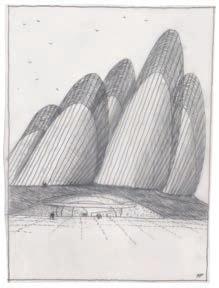

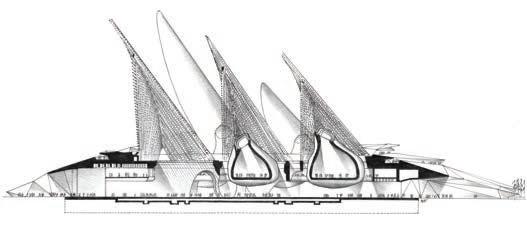

Opening this December, The Zayed National Museum reimagines the concept of a national institution for the 21st century.

By Charles Shafaieh

150 THE NEW VANGUARD

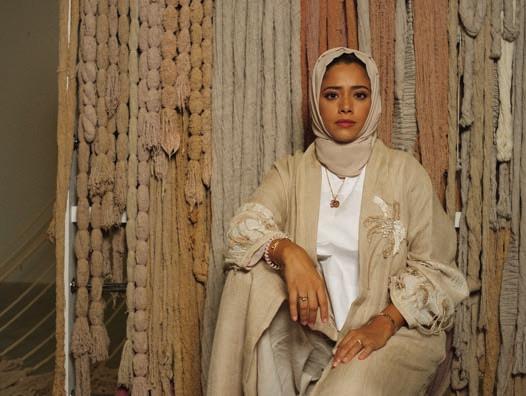

Across Abu Dhabi, a wave of emerging and established artists is thinking bigger—both in scale and ambition— fueled by the city’s rapid cultural rise.

By Katy Gillett

Photography by Natalie Lines

158 ABU DHABI INTEL

What’s new in the emirate this fall.

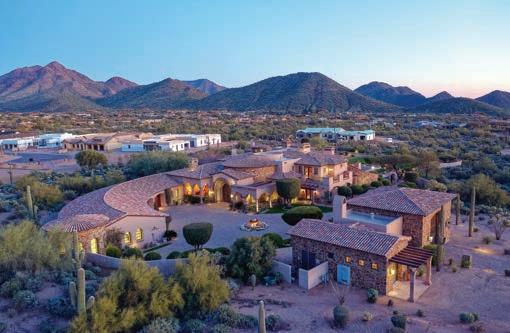

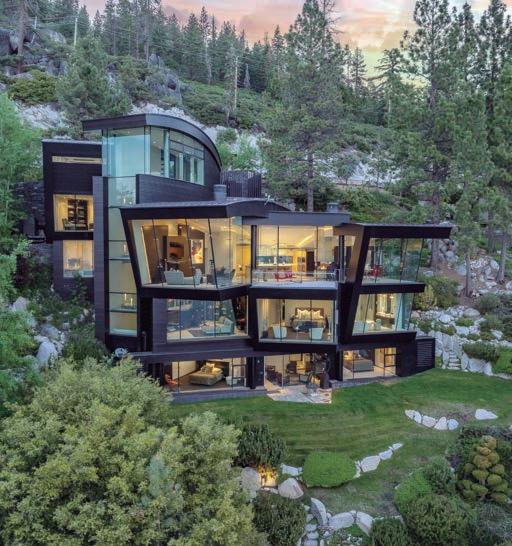

164 EXTRAORDINARY PROPERTIES

Partner content by Sotheby’s International Realty.

176 GOING, GOING, GONE

Breuer’s tubular triumphs.

By James Haldane

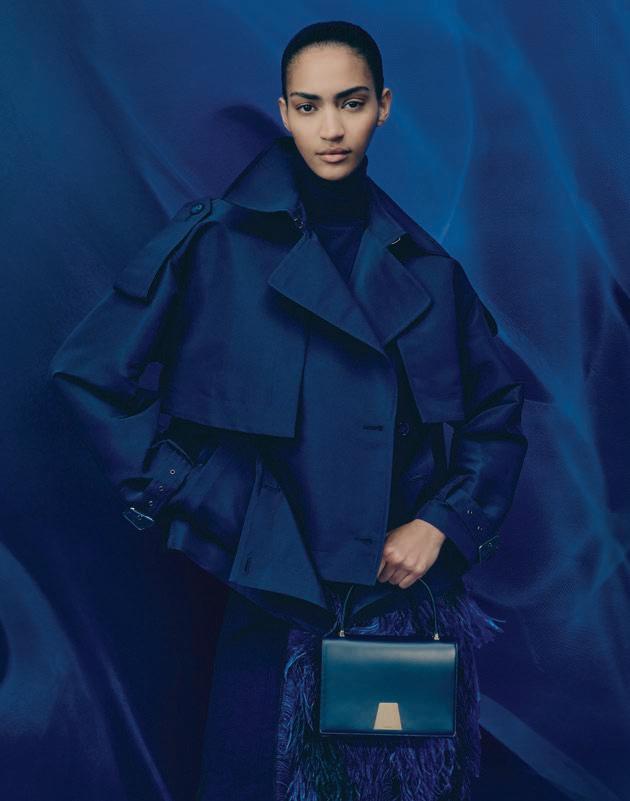

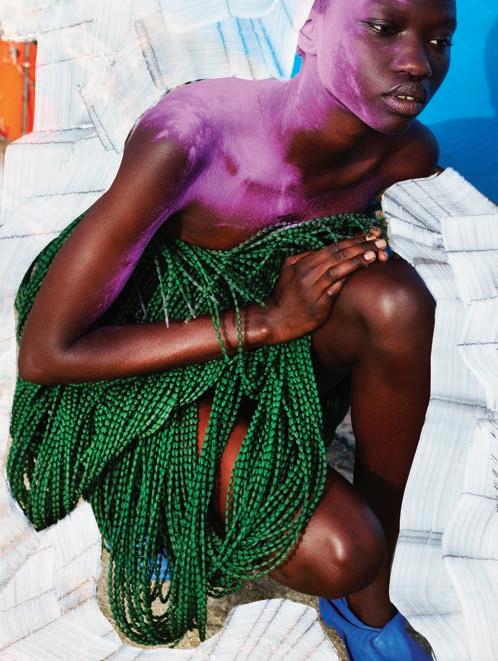

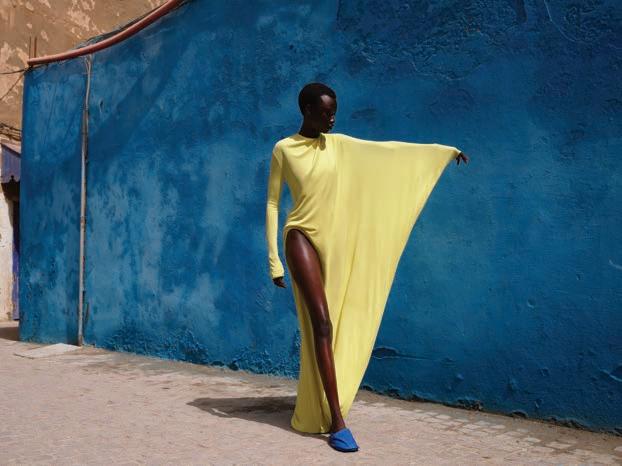

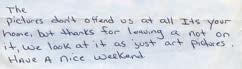

Clockwise from top: Model Anyiang wears a Balenciaga dress, stylist’s own hood and Fforme shoes, photographed by Viviane Sassen in Morocco; fabric designed by Anni Albers around 1949 for the Harvard Graduate Center, now in the collection of the Josef & Anni Albers Foundation in Bethany, Connecticut, photographed by Henry Leutwyler; fashion designer Nili Lotan’s Marcel Breuer-designed home in Croton-on-Hudson, New York, photographed by Adrian Gaut; “Realm of Living Things 19,” a work in terracotta by the 2025 Loewe Foundation Craft Prize winner Kunimasa Aoki.

on the cover

The Breuer on New York’s Madison Avenue, photographed on June 9, 2025, by Stefan Ruiz for Sotheby’s Magazine. follow @sothebys on all platforms

Step into an all-inclusive ultra luxury experience that is Unrivaled at Sea™. Explore more than 550 destinations around the world while enjoying the unrivaled space, elegance, and comfort of The World’s Most Luxurious Fleet® We’ll tend to every detail of your journey from start to finish, so you can be pampered by the warm, Heartfelt Hospitality™ delivered by our incredible crew who not only care for you, but about you.

Nobody Does It Better than Regent Seven Seas Cruises®

This fall is marked by doors opening anew—from our relocated New York HQ, housed in an architectural icon, to the storied interiors of an exceptional patron’s London home and the rising cultural landscape of Abu Dhabi.

“What should a museum look like, a museum in Manhattan?” With this question, Marcel Breuer opened his 1963 presentationtothetrusteesoftheWhitney Museum.Ingrapplingwiththeanswer,the Hungarian-born architect envisioned what would become the granite-clad, inverse ziggurat at 945 Madison Avenue—a bold brutalist icon conceived as a deeply considered public space that has since offered visitors the opportunity to encounter not only the Whitney’s holdings but also, over the decades, substantial parts of the Met’s and Frick’s collections.

In our cover story, architectural historian Barry Bergdoll explores both Breuer the man and Breuer the building, soon to begin a new chapter as Sotheby’s New York headquarters. Complemented by behind-the-scenes photography by Stefan Ruiz, shot in June to document the restoration in progress, the story offers a first lookattheworkbeingdonetopreservethe building for future generations ahead of its public unveiling this November, when it will reopen as a cultural hub for all.

Breuer’s legacy resonates throughout the issue—from a visit to fashion designer Nili Lotan’s home, designed by the architect to overlook the Hudson River, to a deep dive with Nicholas Fox Weber, director of the Albers Foundation, into the creative practices and tools of Anni andJosefAlbers,whobothworkedalongside Breuer at the Bauhaus, contributing significantly to the school’s innovative design education and artistic legacy. And onourbackpage,wecelebrateearlyprototypes of his groundbreaking tubular-steel furniture, tracing their near-century-long influence on generations of designers.

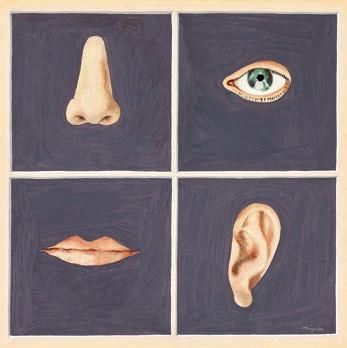

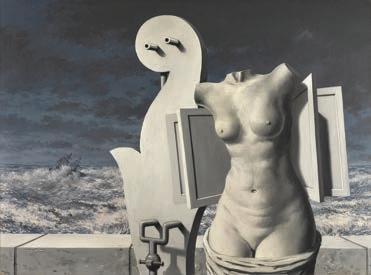

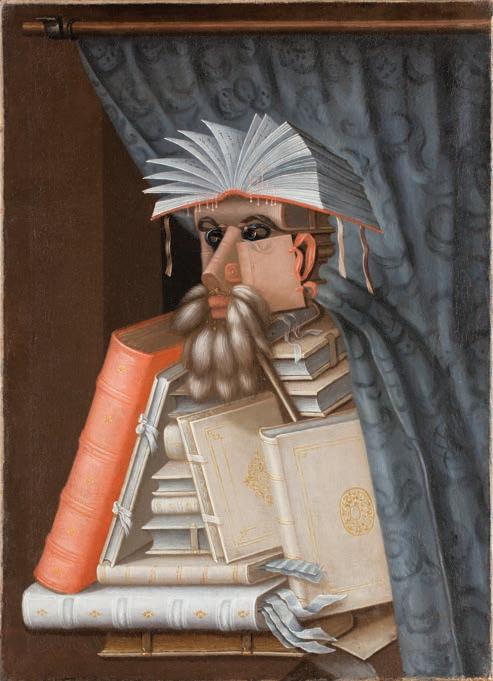

Stepping into another hallowed art space,weentertheLondonhomeofPauline

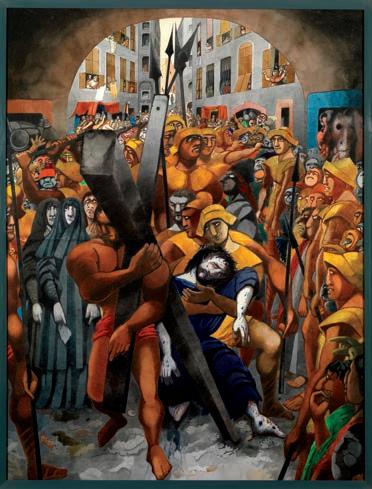

Karpidas, the patron best known for nurturing fresh artistic talent through her annual exhibitions and gatherings on the Greek island of Hydra. The apartment was a more intimate space, animated by contemporary design from the likes of Les Lalanne and Mattia Bonetti, where she gathered the great works that had instructed her eye—an exceptional collection of surrealist masterpieces. The dreamlike abode will be recreated in our London galleries from September 8, ahead of a landmark series of single-owner auctions. This extraordinary early René Magritte (above) is one of the collection’s highlights and its palette runs through our four editorial acts.

Four because we have added a bonus section in recognition of the swell of cultural happenings coming to Abu Dhabi this season, ahead of Sotheby’s inaugural auctions in the emirate. Features include a travel portfolio charting its historic

sites and modern marvels, a group profile of four flourishing artists operating in the capital and a preview of the Norman Foster-designed Zayed National Museum openingthisDecember.AsManuelRabaté, director of Louvre Abu Dhabi, puts it, “Abu Dhabi is building not just museums but a whole cultural constellation that nurtures and inspires.”

Elsewhere, we excerpt photographer Sally Mann’s new book, “Art Work: On the Creative Life,” pay a fashion-infused visit to Morocco with visual artist Viviane Sassen and stylist Alexandra Carl, and learn how the Loewe Foundation Craft Prize is elevating craftsmanship for today. Read on and step through the threshold.

Stefan Ruiz Photographer

Stefan Ruiz is a New York-based photographer who has contributed to The New York Times, Time and Vogue. His work was recently featured at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Monterrey. Ruiz taught art at San Quentin State Prison and served as creative director for Colors Magazine. He has published three monographs and is at work on a fourth.

The Brilliance of Breuer, p86.

Editor in Chief – Kristina O’Neill

Creative Director – Magnus Berger

Editorial Director – Julie Coe

Director of Editorial Operations –Rachel Bres Mahar

Executive Editor – James Haldane

Visuals Director – Jennifer Pastore

Design Director – Henrik Zachrisson

Entertainment Director –Andrea Oliveri for Special Projects

Editorial Assistant – Joshua Joseph

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Akari Endo-Gaut, Frank Everett, Cary Leitzes, Sarah Medford, Lucas Oliver Mill, Amanda Randone

CULTURESHOCK

Chief Executive Officer – Phil Allison

Chief Operating Officer – Patrick Kelly

Head of Creative – Tess Savina

Production Editors – Rachel Potts, Antonia Wilson, Emma Nicklin

Art Editor – Gabriela Matuszyk

Designers – Ieva Misiukonytė, George Hatton, Michael Kelly

Subeditors – Emily Hawkes, Bobby McGee, Ceri Thomas

PARTNERSHIPS

Head of Global Partnerships –Eleonore Dethier

Alexandra Carl Stylist

Alexandra Carl is a fashion stylist and creative consultant based in London. Her aesthetic celebrates androgyny, utilitarianism and irreverence, while maintaining a focus on feminine power. Carl is the author of “Collecting Fashion,” which features notable 21st-century fashion archives, highlighting the wardrobes of leading design and fashion talents. The Artist Portfolio, p68.

Viviane

Based in Amsterdam, Viviane Sassen combines photography, fashion and fine art. She has published more than 25 books and her work has been shown at the MoMA and the Rijksmuseum, among other venues. Sassen’s most recent exhibition, “This Body Made of Stardust,” was on view at Collezione Maramotti in Reggio Emilia, Italy, this summer.

The Artist Portfolio, p68.

Barry Bergdoll Writer

Barry Bergdoll is the Meyer Schapiro professor of art history at Columbia University and former chief curator of architecture and design at MoMA. An author and curator, he has published widely on modern architecture, including works on the Bauhaus and Marcel Breuer. He is the co-editor of “Marcel Breuer: Building Global Institutions” (2018).

The Brilliance of Breuer, p86.

PUBLISHING

US (New York and Northeast) Fashion – Judi Sanders LGR Media Plus judi@lgrplus.com

US (New York and Northeast) Jewelry & Watches – Lisa Fields lisa.fields.consultant@sothebys.com

US (New York and Northeast) Design – Angela Okenica aokenica@gmail.com

US (Southeast and West Coast) Mark Cooper TL Cooper Media markcooper@tlcoopermedia.com

US Galleries and Museums – Ian Scott ECM Consulting ian.scott.consultant@sothebys.com

UK and France

Charlotte Regan

Cultureshock charlotte@cultureshockmedia.co.uk

Italy

Bernard Kedzierski and Paolo Cassano

K. Media bernard.kedzierski@kmedianet.com paolo.cassano@kmedianet.com

Switzerland Neil Sartori Media Interlink neil.sartori@mediainterlink.com

France

Guglielmo Bava Kapture Media gpb@kapture-media.com

India and GCC Region Marzban Patel Mediascope marzban.patel@mediascope.co.in

SOTHEBY’S

Chief Executive Officer – Charles F. Stewart

Chief Marketing Officer – Gareth Jones

Chief Public Relations Officer – Karina Sokolovsky

Global Head of Brand – Jacqueline King

Global Head of Content and Campaigns – Nick Marino

Global Head of Growth – Tracy Heller

Global Head of Social Media and Editorial – Anne Johnson

Global Head of Video Production – Rachel Roderman

Head of Events and Preferred, Americas – Richard Drake

Head of Events, UK – Lydia Soundy

Head of Procurement – Eduardo Guerra

Production Manager – Stephen J. Stanger

GENERAL INQUIRIES sothebysmagazine@sothebys.com

LONDON

SEPTEMBER 17-18

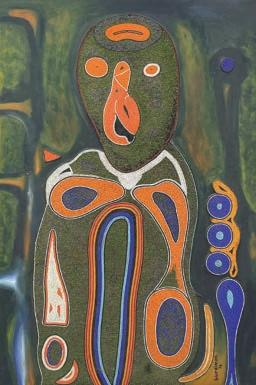

Masterworks of surrealist art and modern design from the collection of a legendary patron and aesthete.

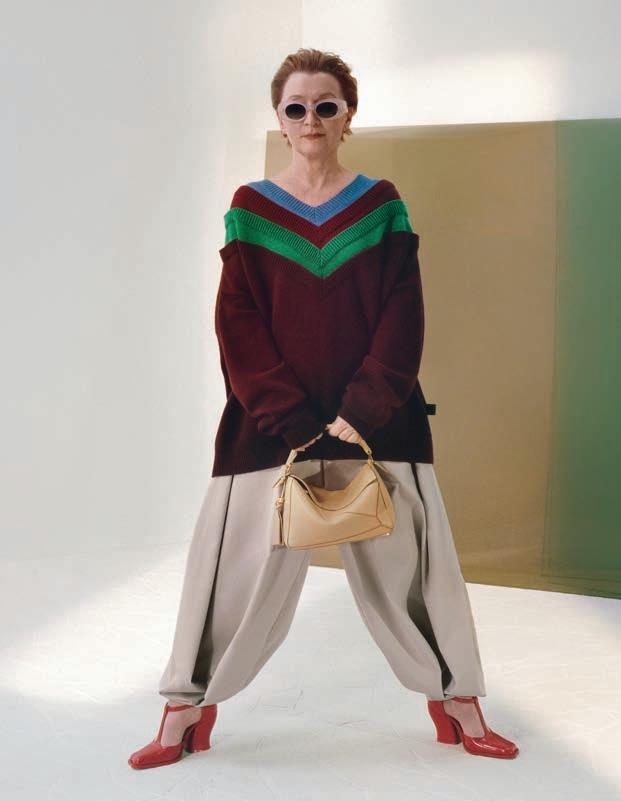

René Magritte, “La Statue Volante,” 1958. £9,000,000-£12,000,000, “Pauline Karpidas: The London Collection Evening Auction.”

NEW YORK SEPTEMBER 26

HERSHEY OCTOBER 8-9

The official auction of the Eastern Division AACA National Fall Meet, which celebrates its 70th anniversary this year.

1934 Auburn 1250 Salon Phaeton Sedan. $250,000-$300,000, “RM Sotheby’s Hershey.”

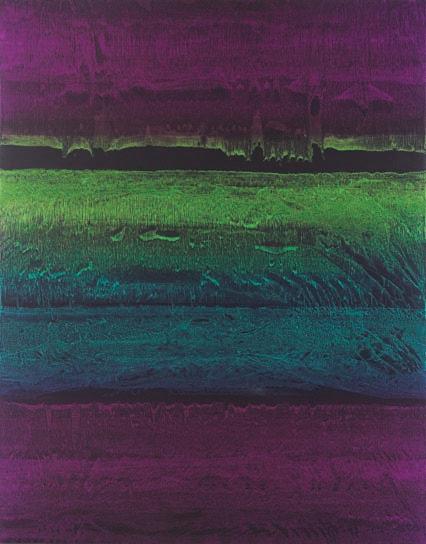

An exceptional array of works from postwar masters to today’s cutting-edge artists.

Sean Scully, “Place 4.8.95,” 1995. $150,000-$200,000, “Contemporary Curated.”

HONG KONG SEPTEMBER 27-28

Modern and contemporary works from Asian and global masters.

Yoshitomo Nara, “Strange Girl,” 1991. HK$2,500,000-HK$3,500,000, “Modern and Contemporary Day Auction.”

NEW YORK

SEPTEMBER 17

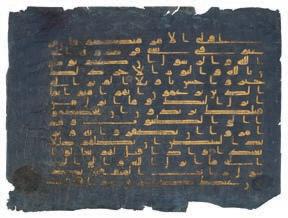

Presenting great masterpieces of Chinese art spanning more than 5,000 years of history.

LONDON SEPTEMBER 30

HONG KONG AUGUST 29 - OCTOBER 21

Showcasing high jewelry, watches, extraordinary handbags, wine and spirits.

A rare and important gilt-lacquered bronze figure of

A rare and important gilt-lacquered bronze figure of Acuoye Guanyin, Dali Kingdom, 11th-12th century. $500,000-$1,000,000, “Chinese Art.”

PARIS SEPTEMBER 15 - OCTOBER 10

Offering a magnificent selection of jewelry, watches, handbags, wine and spirits.

Cartier “Panthère” diamond, emerald, onyx and sapphire bangle. €200,000-€300,000, “Fine Jewelry.”

The finest examples from the region’s established and emerging artists, spanning a variety of mediums.

Sayed Haider Raza, “Shanti La Paix,” circa 2000. £300,000-£500,000, “Modern & Contemporary South Asian Art.”

NEW YORK SEPTEMBER 15-29

Celebrating the rich history and cultural significance of sports through exceptional artifacts.

Wilt Chamberlain Los Angeles Lakers 1969 NBA Finals GameWorn Jersey. $1,500,000$2,000,000, “September Sports Sale.”

Burmese unheated ruby and diamond necklace. HK$5,500,000-HK$8,000,000, “High Jewelry.”

EDINBURGH OCTOBER 10

The world’s most distinguished ultra-rare whisky auction, with proceeds benefiting The Distillers’ Charity and The Youth Action Fund.

A dial known only to the wearer lies hidden beneath the links of this Van Cleef & Arpels bracelet.

Like the Looping braceLet it adorns, this jeweled timepiece traces interlinked chapters in the history of Van Cleef & Arpels. Its name originates with the “Ludo” bracelet, a design introduced in 1934bycompanycofounderLouis“Ludo” Arpels. Arpels envisioned an innovative new form, with links shaped in either a brick-like pattern, as seen here, or a honeycomb-style mesh. In both versions, the joints are expertly hidden, creating a sinuous, ribbon-like effect that wraps the wrist with elegant ease.

Soon after, the motif was transferred to the house’s timepieces and into the heightened language of fashion-

influencedlateartdecostyle.Thebracelet is punctuated by a buckle motif befitting a couture belt and, instead of foregrounding the rectilinear shapes of the 1920s, the case is defined by two diamond-set circles—balancing strength and softness in a single form. It is only by pinching together the two circles that the wearer reveals the hidden face.

Before the 1920s, watches were not worn on the wrist, instead taking the form of either pocket watches, or more commonly for women, lapel watches. Thus, it was a period of transformation, and a creative challenge approached in different ways. Cartier’s “Tank,” released to the public in 1919, sat boldly on the wrist: proud, visible, graphic. By contrast, in 1931, Jaeger-LeCoultre released the “Reverso” based on a patent filed earlier that year. Designed to withstand the rigors of a polo game, its mechanism was housed in a case that could be flipped

BY ANDRES WHITE CORREAL Chairman, Jewelry, EMEA

to protect the dial. The “Ludo” was of course targeting a different demographic—the stylish, avant-garde women of the interwar period.

This play between innovation and elegance, between mechanism and mystery, is at the heart of Van Cleef & Arpels’ identity.Unliketheovertengineeringbravura of early men’s watches, the “Ludo Secret” celebrates discretion and wit. Its hidden dial is not just a technical feat; it’s a gesture of intimacy, known only to the wearer. That sense of secrecy, of something precious tucked away behind beauty, elevates it beyond a timekeeper into the realm of personal ornament.

The house understood that for their avant-garde clientele, femininity and modernity were not opposites. Its signature serti mystérieux (mystery setting)—used for the rubies of this piece—exemplifies their drive to merge high jewelry with high innovation. The stones appear to float weightlessly across thesurface,theirmountingshidden,their sparkle uninterrupted.

Recently revived and reissued by the house, the model retains the spirit and silhouette of the original. This reappearance underscores the enduring relevance of the design: fluid, stylish, technically masterful and unmistakably Van Cleef & Arpels. Reimagined for collectors nearly a century later, the “Ludo Secret” remains a triumph—not only of craftsmanship, but of vision. For those drawn to the secret-filled timepiece, however, it may be worth seeking out an earlier example. Thevintagepiecestendtocarryawarmth and character that’s difficult to replicate.

As told to James Haldane

Arrive

Request your private consultation

A British classic, expertly transformed by Mulliner, epitomizes the graceful end of a legendary coachbuilding tradition.

“EvEry Cloud has a silvEr lining,” the definitive book on one of RollsRoyce’s most famous models, celebrates this 1962 Cloud II Drophead Coupé Adaptation by H.J. Mulliner as the end of an era. Author Davide Bassoli, an expert on luxury British marques, identifies this car succinctly as “the last one built… with gorgeous lines, perfect proportions.” Only 107 Mulliner-adapted Drophead Coupés were built on a Silver Cloud II chassis—a collaborative creation that is generally accepted to be amongst the most elegant of all postwar coachwork— and this particular vehicle marks the final one.

Mulliner, a name now more commonly associated with the personalization of modern Bentleys, was historically an independent coachbuilder that can trace its roots back to a business in 1760s Northampton, England, which built and maintained coaches for the Royal Mail. It morphed through the 19th and early 20th centuriestobecome,bythe1930s,focused

almost entirely on adapting Rolls-Royces andBentleysatatimewhenluxurymotorcar ownership was rapidly expanding among Britain’s middle and upper classes.

In the U.S., where this car was destined, car ownership followed a similar line, expanding significantly after World War II, particularly during the 1950s and 1960s. This specific vehicle—chassis number LSAE639—should not, however, be misunderstood as anything less than a top example. It was created at a time when the coachbuilder would make modifications so extensive that the resulting car was, in its every detail, essentially a fully custom body. The “adaptation,” as it is known, in this case meant modifying a factory-standard steel saloon body into a convertible by removing the roof, fitting two doors in place of the usual four and adding a modified chromed waistline molding. The adaptation, notably, is one of just 74 left-hand-drive examples of the Cloud II built by H.J. Mulliner.

Copies of its original chassis cards, which are on file, indicate that the car was specially ordered by Boyd Calhoun Hipp, of Greenville, South Carolina, a decorated World War II hero who became aleaderintheinsurance,financeandtelevision broadcasting industries. Mr. Hipp requested a left-hand-drive, U.S.-specification model with a power radio aerial

BY GORD DUFF President, RM Sotheby’s

and windows, the newly developed Rolls-Royce air-conditioning system, and special Sundym glass.

Mulliner also installed an array of special features supplied by London coachbuilder Harold Radford, including Perspex sun visors, a fitted locker with an ice thermos in the left-hand door pocket, fitted cocktail bars with three spirit flasks and six tumblers in the backs of the front seats, and most amusingly, removable “toadstool” cushions that affix to the rear bumpers, providing seating for elegant “tailgate” dining in the most literal sense.

Hipp accepted delivery of his Silver Cloud II in England in September 1962, with records indicating that it accompanied him home to New York in the most stylish of fashions, aboard the fabled Cunard liner the HMS Queen Elizabeth.

The car was later restored in previous ownership, and it still presents beautifully in Sand with fine red coachlining and an interior luxuriously trimmed in Magnolia Connolly hides, Cumberland Stone Wilton carpeting and a Fawn West ofEnglandheadlinerunderafreshmohair top. Correct whitewall tires augment the car’s chic yet sporting stance.

Whether in motion or on concours display, historians generally consider the rare Silver Cloud II coachbuilt cars as offering the best of all Rolls-Royce worlds: superior engineering, fine quality andtimelessdesign.Thiscar,asthelastof a proud series and one filled with bespoke features, is particularly special, and it will find a home in any fine collection of cars bearing the Spirit of Ecstasy.

RM 30-01 Le Mans Classic

Skeletonised automatic winding calibre

55-hour power reserve (± 10%)

Baseplate and bridges in grade 5 titanium

Declutchable variable-geometry rotor

Oversize date and 24-hour display

Case in grade 5 titanium and Quartz TPT® Limited

ACT ONE

The Opening Bid, in which we present news from the worlds of art, books, culture, design, fashion, food, philanthropy and travel. Alongside The Global Agenda, which highlights not-to-be-missed exhibitions opening in September.

Edited by Julie Coe

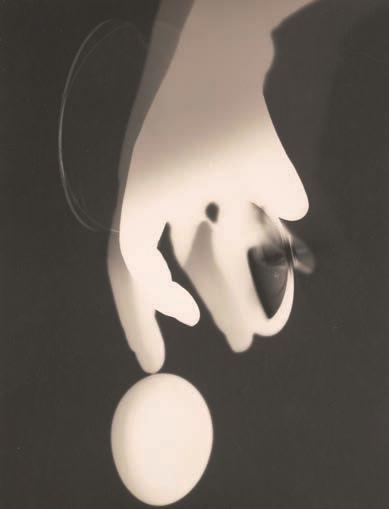

The ingenuiTy of Man Ray, a key figure in the surrealist and dadaist movements, comes to fresh light this fall in an exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art that focuses on his photograms—or Rayographs, as he called them. Opening September 14, “Man Ray: When Objects Dream” is the first show to highlight Ray’s use of this rudimentary technique—placing objects on photosensitive paper—and the ways he brought out its rich possibilities, experimenting with unexpected materials and multiple exposures. The first Rayograph dates to 1921, when the Philadelphia-born Ray had just arrived in Paris. He would spend the next 18 years in the city, part of the vibrant Montparnasse scene. One of his collaborators there was fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli, and her namesake fashion house is among the sponsors of the Met exhibition. The label’s creative director Daniel Roseberry feels a connection with Ray, who was also an American making his way in Paris. “Man Ray’s imagery feels at once specific to its time and eternal,” Roseberry says. “It’s something I think about often in my own work: how can we capture people’s imagination by showing them something new, something revelatory, while also reminding them of where we’ve come from?”

According to the origin story of plov, the national dish of Uzbekistan, it was created to cure a lovesick prince who wanted to marry a craftsman’s daughter. The first Bukhara Biennial, titled “Recipes for Broken Hearts,” takes its name from this tale. Artistic director Diana Campbell is pulling together many of the story’s threads—namely, craft and food—for the event, which opens September5.ManybiennialartistsareworkingwithUzbekcraftspeople to create pieces expressly for the show. “In 2025, the craftsman’s daughtershouldhaveaname,”Campbellsays.

“They should all be invited to the table.” For example, Tavares Strachan is working with an artisan to weave Langston Hughes poems into a carpet, while Laila Gohar is building a rock-crystal house from a local grape-juice sugar. “If you’re traveling to Uzbekistan to see contemporary art,” says Campbell, “it’s important that you’re not seeing anything you can find anywhere else in the world.”

From top: Caravanserai Ahmadjon, a setting for the Bukhara Biennial; a painting of Oyjon Khayrullaeva’s project, by artist Yunus Farmonov, 2025; the entrance to Bukhara’s Khoja Kalon and Kalon Minaret.

With outposts in Paris and New York, the Amelie du Chalard Gallery has become a resource for top interior designers over its 10-year history. One such talent, Kelly Behun, will inaugurate a guest curation series at the Manhattan showroom this fall, outfitting the space with her own picks from the gallery’s 80 artists.

Harmony: Helene Kröller-Müller’s Neo-Impressionists opens at the National Gallery in London.

The counTdown is on for the final few weeks before the five-year closure of Paris’ Centre Pompidou. Celine is even sponsoring free access on the last day, September 22. Wolfgang Tillmans’ aptly titled show, “NothingCouldHavePreparedUs–EverythingCould Have Prepared Us,” is the appropriate swansong beforerenovationsbegin.TheGermanartisthastaken over the museum’s vacated 64,500-square-foot Public InformationLibrary,fillingitwithnearlyfourdecades’ worth of his photographic work, which ranges from the political to the poetic and often mixes the two.

Wolfgang Tillmans’ “Power Station (Low Clouds),” 2023.

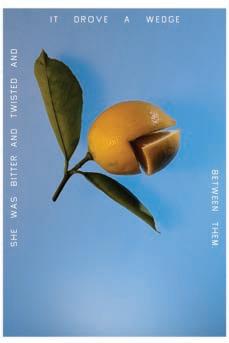

ArTisTedruschA andchefRuthie Rogers, of London’s beloved River Café, were meandering through a grove behind Ruscha’s Los Angeles studio last year when the surroundinglemontreesgavethem the idea for the cookbook they’d always wanted to do together. The result is “Squeeze Me: Lemon Recipes & Art” (Rizzoli), a series of sweet and savory concoctions —from lemon fennel seed biscuits to sea bass carpaccio with lemon and tomato—accompanied by new works Ruscha created with his classic Boy Scout Utility Modern font. LoveFrom, Jony Ive’s studio, contributed the overall design and theaphoristictexts.“Alemonisnot justfruit,”readsone,“itisamood.”

The latest from Technogym’s collection of sleek exercise equipment is the Reform, a Pilates reformer that comes in three colorways (Sandstone, shown, Diamond Black and Pearl Grey), features nauticalstrength ropes and vegan leather, and helpfully stores upright to save space.

the national art center tokyo is the brilliant setting for “Bulgari Kaleidos: Colors,CulturesandCrafts,”openingSeptember 17. Displaying nearly 350 pieces from the Italian jeweler’s archives and private collections, the exhibition will examine Bulgari’s use of colorful gemstones across three themes: scientific aspects, cultural symbolism and light’s functioninperception.

Contemporary artists Lara Favaretto, Mariko Mori and Akiko Nakayama were each tapped to contribute new works. Favaretto has repurposed car wash brushes as kinetic sculptures, while Mori has built one of her “Onogoro Stone” pieces, inspired by Japanese mythology. Nakayama’s installation mixes together

water, sound and pigments to form fluid, real-time projections. In designing the exhibition as a whole, Japanese firm SANAA and Italian studio Formafantasma referenced both Roman mosaics andgingkoleaves.

The show traces Bulgari’s evolution from traditional designs to its postwar embrace of vibrant gems such as amethystandturquoise.Amongthekeypieces on display are a convertible 1969 sautoir necklace set with a rainbow of precious stones and a 1961 emerald necklace worn by Italian movie stars Gina Lollobrigida andMonicaVitti.

Bulgari Heritage Collection bangle in gold and platinum with rubies, sapphire and diamonds, 1954-1955.

In the late 1970s, photographer David Wojnarowicz took a series of photographs of friends wearing a mask of Arthur Rimbaud’s face. The black-and-white pictures seem to show the 19th-century French poet resurrected in the crumbling New York City of the late 20th century, eating in a deli, loitering under overpasses, riding the subway, doing drugs. This fall, “Arthur Rimbaud in New York” is the subject of an exhibition of the same name opening at Manhattan’s Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. It will also be exploredinaforthcomingbookfromSkira,edited by the show’s curator, Antonio Sergio Bessa.

Right: David Wojnarowicz’s “Arthur Rimbaud in New York (Coney Island),” a silver print from 1978-79.

To celebrate the opening of the House of Dior New York, the fashion label is rolling out a range of pieces exclusive to the Manhattan flagship, from T-shirts to trays and bags, many in a chic newsprint-style pattern.

Dior Book Tote, $3,600; available

House of Dior New York.

Joel Mesler has seen the art world from many sides, as an artist, dealer and collector. Now he’s added creator of museum merch to that list.

For his new show at Guild Hall inEastHampton,NewYork,titled “Joel Mesler: Miles of Smiles,” he’s set up his “Smile Shop” in the museum lobby, with playful offerings of his own design, from charm necklaces to fruit bowls to brightly painted chairs.

It’s all very much in keeping with his exhibition’s premise, an office-slash-studio space, outfitted with his own works and those of artist friends, where Mesler may or may not be in attendanceduringopeninghours.

Creatures and Captives: Painted Textiles of the Ancient Andes opens at the Dallas Museum of Art in Texas.

Your time is precious, so spend more of it how you like. The unparalleled flexibility of Airshare gives you the freedom to get there faster, stay a little longer, and make more memories along the way.

Unlimited hours* each day you fly

Immediate availability in the Challenger 3500 and Phenom 300

Industry-leadinginterchange rate to maximize efficiency

Up to 25%savings when your trip begins and ends in the same location

Whether you choose Fractional Ownership or the EMBARK Jet Card, Airshare ensures you get the most out of every day.

Opening september 12, “Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale” sees the Crawley family struggling to preserve the titular Yorkshire estate. As they face death, divorce and debt, jewelry plays a role in underlining their challenges.

The show’s longtime costume designer Anna Robbins turned to London estate jeweler Bentley & Skinner to assemble a collectionofpiecesthatwerebothhistor-

ically accurate for the 1930s and reflective of the story arc. She first considered what might be passed down from the family matriarch, the recently deceased Violet Crawley, Dowager Countess of Grantham. In one scene, for example, her granddaughter Lady Mary wears one of Violet’s brooches. “We were also really clear that [Violet’s] garnet ring would become part of Mary’s everyday jewelry,” says Robbins.

To give sartorial symbolism to the scandalousness of Mary’s divorce, Robbins paired a red-silk dress cut on the bias with a diamond Art Deco brooch fastened at the base of a low back. “There was something about entering into the 1930s that galvanized us,” Robbins says of the

bold looks seen on both Mary and her sister, Lady Edith. “There was a new sense of creativity.”

The wealth of tiaras in the film may seem to run counter to the Depression-era setting, but the Victorian- and Edwardian-era pieces reflect the realities of an aristocraticfamilypastitsfinancialprime. “These are heirloom pieces. What’s on display is what they’ve got to lose,” says Robbins of the tiaras. “They would probably sell their jewelry before they sold the estate.”—

Shannon Adducci

Above: Michelle Dockery as Lady Mary Crawley, wearing a 1930s tiara featuring a diamond “flower,” Andrew Prince reproductions of 1920s earrings and Art Deco fan-shaped brooches.

One day during the pandemic, Frédéric Biousse and Guillaume Foucher got in the car and set out from Paris for a strategic roadtriparoundBrittany.Theco-founders of boutique hotel group Fontenille Collection were on a mission to find the next location for their growing brand. “We did a complete tour, north, west and south,” says Biousse of their coastal drive.

They came across an old, family-owned hotel in the town of Perros-Guirec, with panoramic Atlantic views. Biousse texted the owners, who initially weren’t interested in selling—until a few months later, when they had a change of heart. “They liked the fact that we loved the property,” says Biousse. “They knew that we would upgrade it, but we would keep the feel. We would keep the family history, the heritage. It happens a lot like this.”

Les Bassans, which opened in June, is the 12th Fontenille Collection property, and the ninth in France. “We always select buildings that are historically anchored in the region,” says Biousse, who has a background in fashion and co-founded

the investment firm Experienced Capital. Foucher serves as the collection’s artistic director, overseeing an internal design team that handles all the renovations. He has a PhD in art history and worked in the Louvre’s sculpture department before becoming an art advisor and gallerist. “This is why you always find a unique sensitivity in terms of architecture, design, arts,” says Biousse. “Each of the hotels has its own personality, but globally, when you go from one to another, there’s this throughline that unites them.”

The first property in the collection was Domaine de Fontenille, an estate in the Luberon that opened in 2015. Additions since include Domaine de Primard, Catherine Deneuve’s former home near Giverny; several island hideaways (on Menorca and Île d’Yeu); and a Tuscan vineyard. As Fontenille has grown, it has attracted investment from LVMH and France’s Caisse des Dépôts, a state investment agency, and at least four more hotels are in the pipeline, in Aix-en-Provence, Burgundy, Chamonix and Florence.

Maison S. is a six-room guesthouse in the picturesque hillside town of Chenjiapu, in China’s Zhejiang province. Created by collector and investor Catherine Chen, the hotel has a museum of local artifacts, from Song dynasty pottery and antiquarian books to age-old deeds and other paperwork that illuminate village life.

Below: At Maison S., a set of seals engraved with Zhu Bolu’s “Household Maxims.”

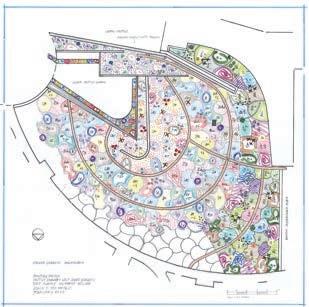

One Of PhiladelPhia’s most famous sons, Alexander Calder, will soon have a new institution dedicated to his work. Opening September 21 on the city’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Calder Gardensfeaturestheunmistakable floral wizardry of Dutch landscape artist Piet Oudolf, renowned for his work on New York’s High Line. Adjoining the grounds is a roughly 18,000-square-foot structure by Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron,

Martin Puryear: Nexus opens at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. The Museo Casa Kahlo opens in Mexico City.

meant to provide a sense of seclusion from the surrounding city. Through these spaces will rotate a trove of works held by the Calder Foundation, led by the artist’s grandson, Alexander S.C. Rower. The kinetic, dynamic nature of Calder’s sculptures is reflected in the programming, which is set to include concerts, performances, talksandmindfulnessactivities.

Above: Piet Oudolf’s planting design drawing for part of Calder Gardens.

Wautier:

at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. The Sculptor Prince opens at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

Inspired by Versailles’ Hall of Mirrors, the Silver Corridor at New York’s Waldorf Astoria had lost its regal bearing over the years, tarnished by smoke and grime.As part of the hotel’s SOM-led renovation, the 19th-century Edward Simmons murals have been expertly restored to their former glory, while the mirrors and chandeliers have regained their original shine.

In which we delve into the minds of creators and collectors, discussing the long-sought works that got away, tracking the place art has on our walls, learning from artists’ well-loved tools of the trade and parsing the psychology behind it all.

A lifelong collector and advocate for self-expressive spaces, August opened her New York gallery, Raisonné, in 2023 to champion mid-century French and radical Italian designers and their contemporary successors.

BY JAMES HALDANE PHOTOGRAPHY BY VICTORIA HELY-HUTCHINSON

Describeyourcollectioninthreewords.

Minimal, restrained and distilled. I like works that possess the artist’s most essential elements. As a 21-year-old, my parents took me to an artist’s studio in Brooklyn to select a college graduation gift. It turned out to be Basquiat’s studio, and I chose a drawing that had a crown on it because he explained that it was his symbol.

What was your very first collection, maybe as a child or a teenager? I’ve always had a passion for collecting. It started when I was very young with a penny collection. When I was in high school, I was a tomboy, so I started flipping baseball cards. On weekends, I would travel to conventions and teach myself which ones were important.

Why do you collect? It comes from a desire to be surrounded by beautiful things and has transformed into wanting to create an environment for friends and family. Iwasanarthistorymajor,soIhada creativesideandIlovedspendingsummers going through the Paris flea markets. I dabbled in the furniture, but it wasn’t until I got married that I started doing it seriously. I’ve always been interested in art and design, but I feel like design has been put on the back seat by collectors and institutions. Collecting creates everevolving spaces. When you keep adding, it

becomes a living narrative. Now I have art too, and it all makes a very good cocktail.

Does art play a role in your romantic relationship? When I married my husband, Glenn, he asked me what IwantedformybirthdayandIsaidIwould like to collect one painting together each year. The first painting was a white [Lucio] Fontana. My husband thought I was completely crazy, but I still look at it and have a visceral reaction. Arte Povera was always my favorite period.

Who is your collecting wingman? It’s Glenn. I’m the one who drives the collection—I always say that he’s my finance partner—but I feel strongly that we should do it together. I challenge him, but I know that he gets as much pleasure from it as I do.

What artwork or object have you restored back to life? It was a small seascape painting by [Gerhard] Richter. It had an imperfection that was barely visible to the naked eye. I couldn’t see it, but somehow Glenn uncovered it. So when we bought it, we had Richter sign off on touching it up—you don’t often have a living artist to be able to do that. It still bothered my husband, though, so we sold it about 15 years ago. We did very well, but we would have done even better if we

had kept it. Now, when Glenn wants to sell something, I say, “Just remember the Richter, honey.”

Who is the most unjustly overlooked artist? Félix González-Torres. He had ashortcareer,buthisartisstillsorelevant because it involves the viewer and deals with the fragility of life. During COVID-19, the gallerist Andrea Rosen arranged for around 400 participants to each exhibit his 1990 work “‘Untitled’ (Fortune Cookie Corner).” I was living in the Hamptons with my family at the time and was able to create a homage to González-Torres in my conservatory. I posted it on Instagram and people made appointments to come and see the work. Everyone got to go home with a fortune.

Favorite art fair and why? I love Paris Design Week every September. A lot of design starts there.

Favoritecuratorandwhy? I am obsessed with Hans Ulrich Obrist. He’s a genius, a true advocate for artists and he loves to connect people. He puts on incredible shows at the Serpentine Galleries in London.

What’s the piece that got away? In 2015, a friend came to me who was trying to put together a group of people to buy

a Gonzélez-Torres work made up of green candies wrapped in cellophane. The piece has interesting bylaws—it can be owned by more than one person, and it can be on display at more than one place at a time. I think there were nine of us and it was such a genius idea, so I was excited to participate.Aswefoundoutlater,wewere beaten at auction by [philanthropist and art patron] Alice Walton, so I don’t think we were even close.

What “tools of the trade” do you use to keepbuildingyourcollection? Auctions, galleries, connections—everything. And I just never know where things will end up. I bought a 13-foot Charlotte Perriand “Nuage” bookcase from Phillips years ago withouthavingaplacetoputitbecauseI’d never seen one that size before. It wasn’t until I moved into my current home that I installed it. When I was just married,

I bought 40 beautiful panels of 18thcentury parquet de Versailles flooring. I never wanted to install it in a home if it wasn’t my final destination, so I waited 25 years until I moved into where we live now.

Favorite work of architecture and why? I love the softness of Tadao Ando’s concrete and the way he incorporates light and landscape into his designs. I was just at the Chichu Art Museum [in Japan], which I thought was incredible.

How has your taste changed through time? My gallery in SoHo, Raisonné, is a relatively recent development in my collecting journey. I had a dealer friend who kept saying that I needed to meet this guy with a store in Brooklyn. I used to say: “Why would I go to Brooklyn if I could go to France to buy furniture?” That guy

was Jeffrey Graetsch, Raisonné’s director, whom I now call my encyclopedia because of his knowledge of designers and where to find things. We decided that it was the right time to open a gallery because New York didn’t have a great design gallery. It’s filled with masters of furniture from the 20th and 21st centuries, alongside carefully curated art.

What was your wildest white-knuckle moment at auction? I bought a Paul Dupré-Lafon coffee table a long time ago from Sotheby’s. There was a lot of fighting but it’s still one of my favorite pieces. But I’ve never bought anything live in an auction room. I prefer to be at home as I don’t like seeing who I’m bidding against. I have taken calls in crazy locations in order to get things though. I was once in the middle of an interview for my daughter’s high school admission and I stepped out to bid on a Jean Prouvé metal cabinet that I’d never seen at auction before.

Whattipsdoyouhaveforcollectorsjust starting out? Buy what you love. Even if it doesn’t appreciate in value, you will still love living with it.

Do you have a family heirloom, inherited or acquired, to pass on? I have an heirloom for my kids. About 20 years ago, I went to the Whitney Biennial and became obsessed with a 12-foot letter “X” painting by Wade Guyton. It was minimal and sexy. At the time, he didn’t have a gallery, so it was hard to get in touch with him. Somehow, I got his phone number and he basically said: “OK, I’m going to call Home Depot and buy two pieces of wood, and I’m going to send the paint to your house, and I’ll build it in your yard and install it for you. $8,000.”

Favoriteart-relatedbook? There’sabook about Maja Hoffmann’s collection called “This is the House that Jack Built.” Rirkrit Tiravanija did the custom font and the pictures are incredible.

Which collectors do you admire? Emily FisherLandau.Ihadthefortuneofvisiting her home in Palm Beach. She was also interested in design and art. People who bring both into their home and live with it make more interesting collectors for me. •

Opposite page: August’s collection of ceramics, lacquer objects and design monographs.

This page, clockwise from top left: Jean Michel Basquiat, “untitled,” 1984; The white Fontana bought for August as a birthday gift in her first year of marriage stands over design objects including a René Lalique “Spirales” vase; Andy Warhol, “Campbell’s Soup Cans,” 1962; room containing On Kawara, “May. 7, 1980,” and “Apr. 16, 2000”, Jim Hodges, “Movements (variation 111),” 2008, Sol LeWitt, “1,2,3,” 1978, and Piero Manzoni, “Achrome,” 1958.

In an ongoing column, a psychologist and a curator delve into the various meanings behind the act of collecting, exploring its significance both for individuals and society as a whole.

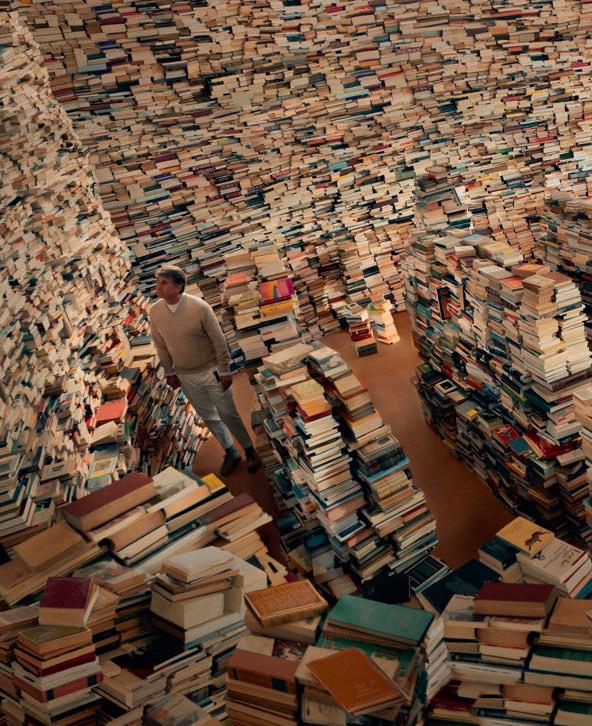

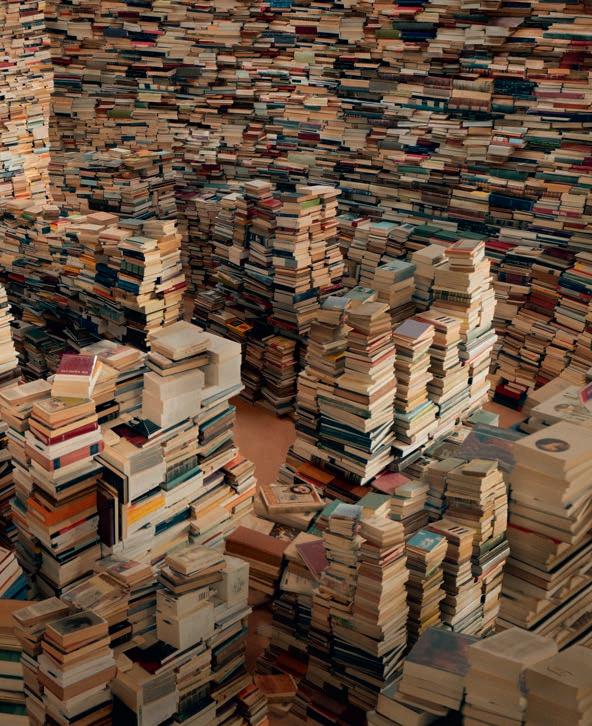

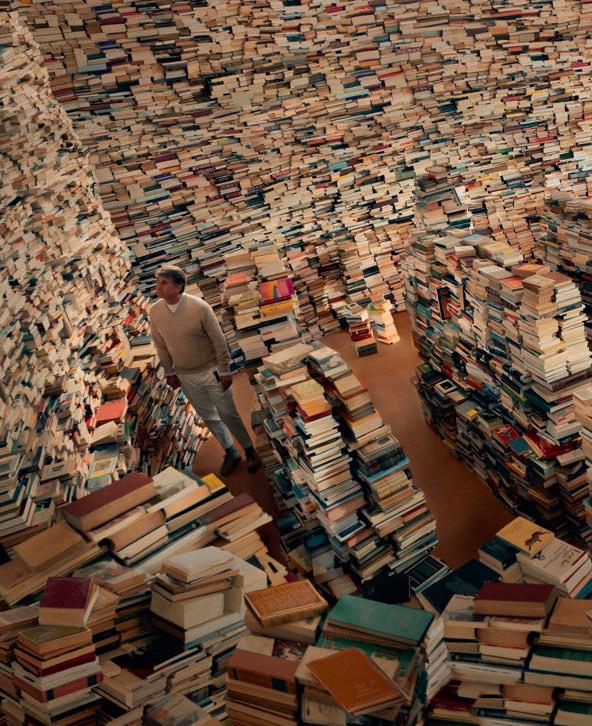

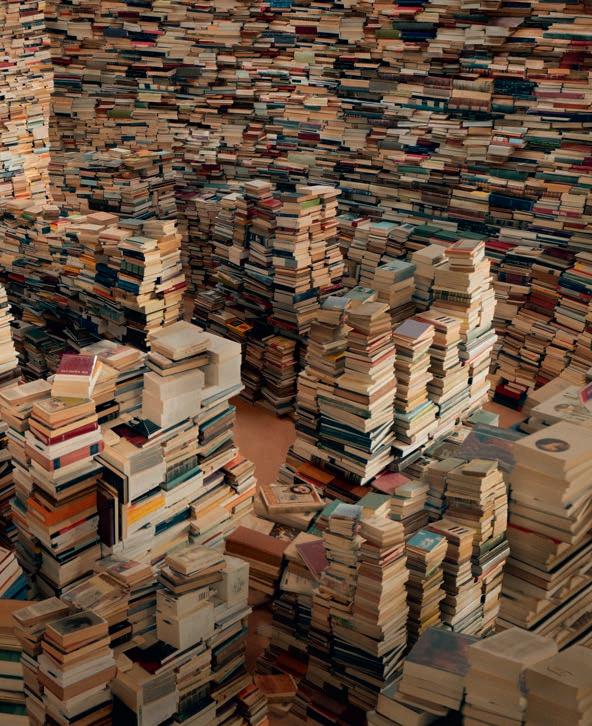

BY ORNA GURALNIK AND RUBY GURALNIK DAWES

Vince Aletti is A writer and curator known for his photographic criticism in The Village Voice and The New Yorker. He also houses a collection of over 10,000 magazines in his New York apartment, which we toured on a hot summer afternoon, taking in his sprawling library as we slipped past the myriad stacks. Aletti encouraged us not only to look but also to touch any object we might be interested in. If not for his openness, it might have felt illicit to enter a collector’s home. Aletti invited us to participate in, rather than view from a distance, his universe of things. The refusal to store objects out of sight speaks to a radical ethic of presence: objects must be seen, handled and read.

It’s a visceral experience, walking through this world full of richness; one can imagine never needing anything aside from what is already there, at a hand’s reach. It spurred us to think through certain questions: What inspired this intense focus in his collecting practice? What is the psychology behind living with versus storing one’s collection? What distinguishes a collection from an archive?

The act of collecting is often solitary and obsessive, yet Aletti has created a personaltrovethatisalsoasocialobject— inviting viewers to enter his space, engage in dialogue, share in a mutual curiosity. Though Aletti has cohabitated with his continually growing piles for nearly half a century, his collection continues to surprise even him.

Unlike much of fine art, magazines are mass-produced, ephemeral and timebound; they function both as a reproduc-

tiveformandanoriginalsiteofproduction. As a magazine collector, Aletti is clearly driven by content, context and historical texture rather than obtaining rarity or market value. From the start, Aletti felt buying magazines—fashion magazines in particular—served as a democratized form of art acquisition: in his words, “awayofpickingacollectionthatIcouldn’t afford otherwise.” Purchasing the September 1955 issue of Harper’s Bazaar, for example, not only entailed owning a copy of Richard Avedon’s “Dovima with Elephants,” but seeing the remaining images from that shoot, obtaining a fuller sense of its photographic and social context. “For someone as obsessive as I am,” Aletti told us, “I really like to see everything that went into and supported that picture that we know.” Collecting images in this way is an act of rescue, an effort to preserve what was intended to be forgotten or discarded.

When we asked Aletti about his motivations for amassing such a vast collection of periodicals, he laughed, then explained with a cheeky smile, “It’s one of those things that I think I need to see a psychiatrist for… I haven’t really thought it through. It clearly means a lot to me, and it’s all here.” That left us with the task of speculating. We learned that Aletti’s father, an amateur photographer, died in a plane crash when Aletti was a tender 10-year-old. Aletti’s mother quickly uprooted the kids from Pennsylvania to Florida, where Aletti was suddenly free; he took to reading and doing as he pleased, with little supervision. When we suggested if there could be a connection

between his self-proclaimed obsession with photography and his early memories in the dark room with his father, Aletti at first vehemently disagreed, adding that he “deliberately erased” his father from memory for years. “Who knows why, but I just closed all that down, it seemed like the easiest thing to do,” he continued. Instead, he focused on his mother: “I felt it was [her] loss,” he recalled. “She was really bereft.”

Later in life, however, Aletti became close with the photographer Peter Hujar, who lived across the street, and with that friendship started mending the disavowal of his father’s importance in his psyche. “It was really interesting to spend time with him,” he said. “It wasn’t like it all came back to me, but on some level itwasthere.Itwassuchapleasuretosmell those smells again, recall all of the steps involved. It really took me a long time to make that connection because of how far down I had sort of repressed it all. But now I’m glad to think about my father’s connection to photography.” Aletti’s collection resembles a melancholic structure: an ongoing negotiation with loss, time and cultural forgetting. By the end of our conversation, Aletti revealed that it was clear to him that his collectionservesaspsychologicalscaffolding. The presence of the various materials in his apartment stabilize memory, reject grief and offer comfort, anchoring and stabilizing the self in place. Aletti’s collection serves as a holding environment, a form of somatic assurance that supports not only his work but also his life. •

Shaped by Bauhaus ideals and their escape from Nazi Germany, the Albers became one of the 20th century’s most influential creative duos. For 46 years, Nicholas Fox Weber has led their foundation and now draws from its archive of the couple’s experiments and ephemera to reveal their unpretentious view of life and their serious approach to art and design.

BY NICHOLAS FOX WEBER PHOTOGRAPHY BY HENRY LEUTWYLER

Anni Albers referred toenrollingattheBauhausin1922,two years after Josef, as “arriving at the land of white.” Part of it was wearing white clothing, or in this case, off-white clothing. Both she and Josef had a nuanced sense of style. More broadly, they liked design that was functional, anonymous and timeless.

Josef experimented perpetually. While he showed his art in a very finished form, so that the interaction of color could occur in all its force, he would do studies to find out what paint to use. He might put one color next to a Grumbacher Mars Yellow, and the same color next to a Winsor & Newton Mars Yellow.

He would always apply paint straight from the tube onto a white panel. Once, I asked him to describe his technique. “The way I spread butter on bread,” he replied—adding that he didn’t mean American white bread, but good Bavarian pumpernickel. He also never put a color on top of another color. He said his father taught him that when he painted a door, “you need to start in the middle, put your paint directly on the background, and work your way out. That way, you catch the drips and don’t get your cuffs dirty.”

The paints themselves were the magic, and Josef was precise—not only about the manufacturer but about the particular batch. In 1976, he said, “Nick, I’m trying to find a Winsor & Newton Cobalt Green, no. 184, because there’s a painting that I want to do with a large central square. If I use the one that’s available, no. 205, I don’t get the penetration of one color into another.” I called Winsor & Newton’s American headquarters and was told there was no difference between 205 and 184. Then I said, “I’m callingforJosefAlbers.”Threedayslater,aboxofno.184arrived.

Josef did the painting he wanted with a large central square. He saw the central square as the cosmos, surrounded by the sea and the Earth. He said that the cosmos should not have sharp edges or corners. It was his last painting.

Anni came to textile-making inadvertently, having originally studied painting and tried unsuccessfully to work with Austrian artist and poet Oskar Kokoschka. Then she did some textiles

at the Hamburg School for Applied Arts, but she felt it was too much like needlepoint, before settling at the Bauhaus. Upon arrival, she immediately felt that textiles should not reproduce natural forms, like the ornate damasks and floral patterns she grew up with. Rather, the beauty of textiles lay in their content.

She allowed thread and its interlacing to be the source of beauty itself. For her earliest wall hangings, she was attracted to pure geometry, particularly the work of Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, and she was deeply influenced by the geometry of the facades of Florence, where they honeymooned.

Anni was interested in discovering new threads and, while in Italy, she bought a little crocheted cap. It had an elastic quality, so she took it apart and discovered it was made of cellophane. She found worship of natural fibers ridiculous and liked to buy what was available. She would go to Sears Roebuck with my wife to do what she called “treasure hunting.” She said Tupperware embodied the Bauhaus ideal—cleanable, easy to manufacture and elegantly functional.

Anni had grown up in a world of diamonds and emeralds and everything materially had been lost. She was very lucky that her parents, who went to America in 1940, survived the Holocaust. Soon after, she began collaborating with a student at Black Mountain College, Alexander Reed, on a jewelry collection made from hardware store items and inspired by ancient Mexican jewelry. It was shown in New York and Chicago to mixed reviews. But for Anni, the point was never preciousness—it was imagination. Great design, she believed, came from ideas, not materials.—As told to James Haldane

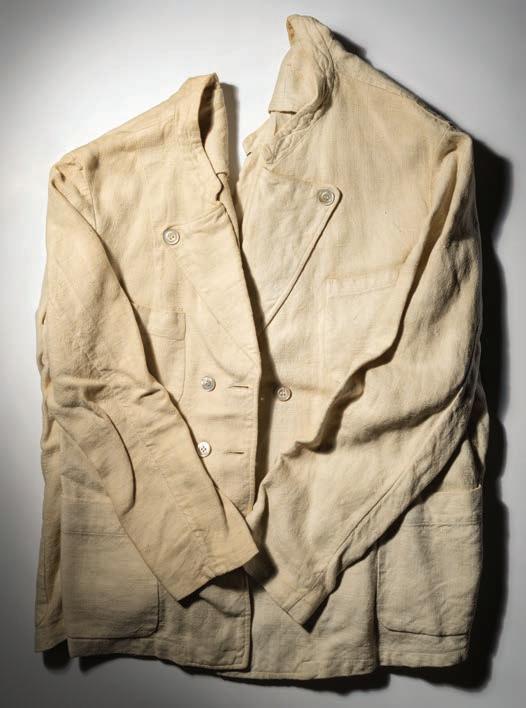

United in simplicity: Anni and Josef’s matching work jackets, possibly sewn by Anni, are preserved in the collection of their foundation, established in 1971 on land in Connecticut that the artists purchased during their lifetimes. Anni, who died in 1994, occasionally sewed garments from simple patterns and was also known to wear her husband’s clothing.

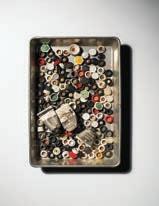

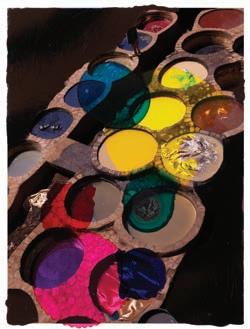

always experimenting, forever exacting Color study with pencil annotations, including Roman numerals—an element Josef, who died in 1976, also used in the titles of his final artworks. Opposite, clockwise from top left: Painter’s knives, which Josef emphasized were distinct from palette knives, used to apply rather than mix paint; a hammer with “Albers” hand-carved into the handle, still in use at the foundation; writing and sketching pencils; red paint tubes from multiple manufacturers; Josef’s model for a geometric decorative design to be installed above a fireplace in collaboration with architect King-lui Wu at Yale University; a pencil foil-stamped with “Josef Albers with love”; objects reflecting Josef’s exploration of color, light and geometry; paint tube lids gathered in a tray—left as they were at the time of Josef’s death; Henri Cartier-Bresson once told Josef that he painted “circular squares”—a description he cherished.

practically minded, imaginatively fashioned

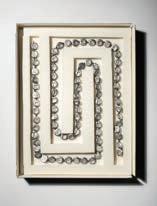

Above: Loom shuttles and metallic thread. Anni often struggled to get the right tools. At the Bauhaus, materials were limited, and when she arrived at Black Mountain College, there was nothing. She had to find what she could locally, but liked the idea of starting from scratch. Opposite, clockwise from top left: Textile tools including a yarn divider, combs and pegs; a necklace made from metal seals, part of a collection created by Anni with Alexander Reed; a mid-20th-century Bakelite magnifying glass; textile samples, including examples combining jute and metallic gold thread; textile-making equipment, including loom shuttles, heddles and a winding tool; a letter Josef sent to Anni in 1955, from Germany, likely while preparing to participate in the first Documenta exhibition in Kassel, West Germany; mini translation dictionaries. Anni was fascinated with language, was bilingual in German and English, and liked miniature versions of commonplace things; further necklaces fashioned from hardware—including a sink strainer, ball chain and paperclips—sometimes combined with grosgrain ribbon; spools of thread designed to fasten buttons and carpets.

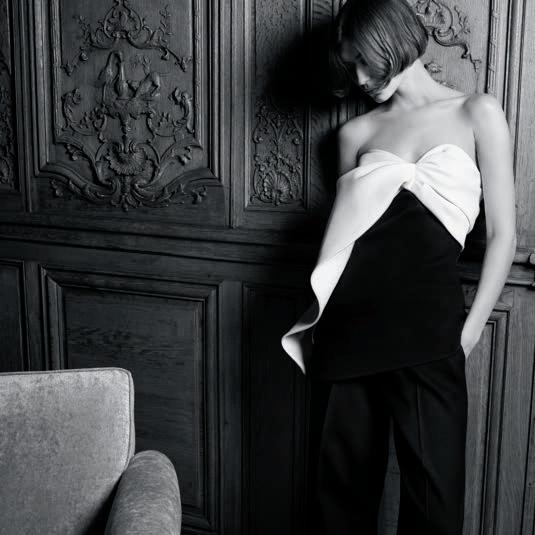

Yves Saint Laurent and Kim Jones, both of whom made their names at Dior, share another thing in common: an elegant Armand-Albert Rateau fauteuil.

BY LUCAS OLIVER MILL

ThemosTpreciousobjecTs ownedbyYvesSaintLaurentand his partner, Pierre Bergé, were housed within their grand salon at 55 Rue de Babylone in Paris. In a moody, wood-paneled room originally designed by Christian Bérard and Jean-Michel Frank in the 1920s, paintings by Mondrian, Brancusi and Picasso hung alongside some of the finest creations from the art deco period. At the center of the salon, two chairs stood side by side. One was Eileen Gray’s “Dragons” chair, which fetched a staggering $28 million at auction in 2009, becoming the most expensive chaireversold.Besideit—quieter,butbynomeansinferior—was a circa-1920 armchair by Armand-Albert Rateau, one of the most enigmatic talents of 20th-century French design. Rateau is often associated with fashion designer Jeanne Lanvin, whose Paris apartment he lavishly decorated in the mid-1920s.

On first glance, the chair is modest compared to the opulence of Rateau’s other creations. Closer inspection reveals that the legs are, in fact, hand-carved into the form of exquisite winged birds, washed over with a jade-green coating. It’s no surprise that Saint Laurent was drawn to this Rateau chair in particular, given his fascination with animal-inspired pieces. “I have a passion for objects depicting birds and snakes, but in real life, these animals scare me,” he once confessed.

In 2009, as the estate of Saint Laurent and Bergé was sold in Paris, the London-born fashion designer Kim Jones followed eagerly from afar. At the time, Jones was the creative director at U.K. men’s label Alfred Dunhill and relatively unknown to the wider public. “I couldn’t afford any of the pieces. I was young. But I was obsessed with their collection,” he tells me as we sit in his North London home. What Jones could not have known back then was that, within a decade, he would step into one of the most storied roles in fashion at Dior, following in the footsteps of Saint Laurent, who led the house’s couture atelier in an earlier era.

Jones joined Dior in 2018 and immersed himself in the house’s archives, drawn to the years shaped by Saint Laurent’s influence.

His fascination with Saint Laurent—both as a designer and as a collector—deepened. By this time, Jones was one of the foremost figures in contemporary fashion and had the means to build the art and design collection he had always dreamed of.

Soon enough, a message came across Jones’ desk at Dior: the Rateau chair from Rue de Babylone was available again. Jones did not hesitate. Though the two fashion designers never met in person—Saint Laurent died in 2008—they were now linked not only by their contributions to Dior, but also by a Rateau chair. (Jones left Dior earlier this year.)

These days, the chair resides in Jones’ home, a two-story concrete and glass structure hidden down a mews street in North London. It’s filled with objects that range from Virginia Woolf’s teapot (another obsession of Jones’ is the Bloomsbury Group) and a first edition of Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species” to a rare pair of Francis Bacon rugs created before the artist turnedtopainting(onlysevenexisttoday).Despitethesheervolume of art, objects, books and ephemera, Jones’ home is far from cluttered. He is a perfectionist. This is perhaps most evident in his library, where custom covers, designed by Jones himself, encase all of his first editions and rare books.

The Rateau chair sits just off the library, in a quiet secondary living room. It’s positioned beneath a small work by artist Tim Breuer, a student of Peter Doig’s, and surrounded by various objects from Jones’ extensive travels. Nearby, a Jean Prouvé cabinet with a green exterior happens to match the legs of the chair perfectly.

Jones’ cat, Dennis, is often found curled up on the chair. One would normally never let a pet near such a piece, but Jones is particularly adamant about living with the things he owns. “Of course I sit in it,” he says, laughing, when I ask if he ever uses the chair. Watching Dennis lounge there feels fitting. Saint Laurent famously kept his French bulldogs close, and they were often found perched on chairs throughout the Rue de Babylone apartment. •

Rue

Yves Saint

in

apartment in 1974, photographed by

To the right is the Armand-Albert Rateau armchair, upholstered in white leather. Saint Laurent would later change it to dark leather.

Right: The Rateau chair, featuring Dennis the cat, in Kim Jones’ London home, photographed by Lucas Oliver Mill for Sotheby’s Magazine. A work by Tim Breuer hangs above the chair, and to the left is a Jean Prouvé cabinet. The larger paintings are by Alex Foxton.

20-24 SEPT. 2025

100 INTERNATIONAL ART GALLERIES 20 DISCIPLINES

Set against Morocco’s vibrant landscapes, centuries-old dyeing techniques ignite a bold, graphic exploration of color and form.

palette cleanse

Essaouira’s harbor, with the 16th-century Castelo Real de Mogador in the distance, evokes centuries of maritime trade between Europe and North Africa. Givenchy by Sarah Burton dress, Fforme shoes and Rellik scarf.

petal push

Melons for sale along the roadside in Sid L’Mokhtar, a small town known for its lively souk. Opposite: The Flatteur Ville, once a French colonial quarter, now home to artists’ ateliers. Prada dress, Zomer skirt and Celine shoes.

ray play

chromaticcrush

bold strokes

A variety of pigments, displayed in a shop in the ancient medina in Essaouira. Opposite: The ancient Sqala du Port d’ Essaouira, an 18th-century bastion once used to guard against European invasions. Calvin Klein 205W39 NYC by Raf Simons Collection dress from Pyrn Archives, Giorgio Armani jacket (worn around waist).

saturation point

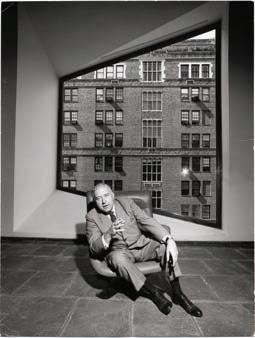

BY BARRY BERGDOLL

PHOTOGRAPHY BY STEFAN RUIZ

In November, Sotheby’s moves its New York headquarters into an architectural masterpiece, the building Marcel Breuer designed in the 1960s for the Whitney Museum—now meticulously restored by Herzog & de Meuron.

In the changing tides of the New York art world, the inverted ziggurat of the former Whitney Museum of American Art building has remained a stalwart presence. The enigmatic granite-clad monument has weathered the ebb tide of its architect Marcel Breuer’s reputation in the 1980s, the tsunami of controversial proposals for major transformations in 1985 and 2001 and then the uncertainty in the wake of the Whitney’s departure in 2014 for its new downtown digs. After a careful restoration by Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron, the building at 945 Madison Avenue—recently given landmark status—begins a bright new chapter this fall as Sotheby’s new Manhattan headquarters. “When I walk through the space, I feel the proverbial ‘pentimenti’ of the exceptional works of artorexhibitionsthatpreviouslyadorned these walls,” says Lisa Dennison, Sotheby’s chairman, Americas, who served on the architectural selection committee. “We have seen how adaptable the building has been to many different styles and periods of art, especially during the residencies of the Met and the Frick.”

“It’s an iconic structure,” says Wim Walschap, senior partner at Herzog & de Meuron, who oversaw the restoration project. “And it stands as a rare example of brutalist architecture designed specifically for public use.” Breuer’s building will again draw the public in to view art, as it was designed to do, while standing as an artwork in its own right—a monument by its Bauhaus-trained creator to sculptural inventiveness.

When it first opened on September 27, 1966,Breuer’sbuildingstoodouteverybit as much as the nearby Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Frank Lloyd Wright’s upwardly expanding spiral completed a few years earlier. At first glance, it seems the very antithesis of the Bauhaus aesthetic, which preferred volumes renderedtransparentthroughmaterialssuch as steel, concrete and plate glass. Breuer himself had achieved early international success with designs of unprecedented lightness and transparency, most notably his tubular-steel chairs and projects for prefabricated houses. The question, then, is how Breuer evolved from a Bauhaus master into a champion of an architectural style dubbed the “New Brutalism”

Wim Walschap, senior partner at Herzog & de Meuron, who oversaw the restoration project.

Opposite: The building’s stairway, which provides city views at each turn.

for its love of robust primal forms and frequent use of unadorned raw concrete (béton brut in French)?

Returning to Breuer’s first freestanding building, the Harnischmacher House (1932) in Wiesbaden, Germany, it’s clear it was an expression of visual lightness, one that reinterpreted interior and exterior through the use of large sheets of plate glass. It featured a steel frame that allowed Breuer to cantilever a porch out over the garden. A veritable showpiece of the modernist impulse,thehousemighteasilyhavebeen featured that same year in the epochal firstarchitectureexhibitionofNewYork’s Museum of Modern Art, which defined the term and characteristics of the “International Style.” Yet Breuer’s built andunbuiltprojectsofthenextfewyears, a period when he was urgently seeking a new base of operations in order to escape Hitler’s rise, portray an emerging sensibility in which natural materials enter into dialogue with industrial ones, contemporary techniques are collaged with traditional construction and the heritage of the Bauhaus takes on a new constructional logic. Soon, Breuer’s architectural language would shift dramatically.

From about 1933 to 1935, the Hungarian-born Breuer shuttled between

Zurich and Budapest, hoping that some opportunity might take root. In fall 1935, he followed his mentor Walter Gropius, László Moholy-Nagy and other Bauhaus figures to Britain. He remained there for only two years, but it was a fruitful, formative period. The Gane Pavilion in Bristol (1936) announced a wholly new sensibility with its complex collage of materials: plate-glass walls set in a frame of load-bearing, rustically cut stone; interiors clad in thin plywood sheets. A wall thatbeganinthegardencontinuedinside, connecting interior and exterior in a way that would become increasingly prominent in his work after he joined Gropius at Harvard in fall 1937.

In the U.S., Breuer focused on developing his ideas for prefabrication, now attunedtodevelopmentsinindustrialized wood. He and Gropius employed wood in structurally innovative ways, as seen in the designs for their own houses in Lincoln, Massachusetts, which face one another across expansive lawns. They attached clapboards vertically (rather than horizontally as was traditional) to the wood frames, laying them flush to maintain the crispness of Bauhaus volumetric composition, and then juxtaposed this with load-bearing chimney walls, made of white-painted brick for Gropius, ofrusticstoneforBreuer.Woodconstruc-

tion allowed cuts into the box to create interpenetrating spaces and patterns of shadow. Breuer began to imagine how he might extend his earlier Bauhaus period research into models for prefabricated transportable houses, suitable to facing the impending housing crisis of the postWorld War II era—although his proposal to create a house with a laminatedplywood frame over a truss-shaped frame, as light and yet as strong as an airplane wing, never advanced beyond study proposals.

In the end his response to the prevailing conservative, neocolonial taste of Levittown and similar models profferedinthepostwarerawastheexhibition “House in the Museum Garden” at the Museum of Modern Art in 1949, by which time he had relocated to New York. With its butterfly roof and “binuclear” plan—in which the bedrooms for parents and children are situated at opposite

ends of the home—Breuer’s concept was a radical alternative to the Cape Cod Colonial Revival.

Pragmatically,thehousewasreplicable by local builders from a set of drawings the architect could provide. Only a few copies are known, but the design brought Breuer some important new clients, notably Rufus and Leslie Stillman, who visited the MoMA house and contacted Breuer for a new house in Litchfield, Connecticut. Over the next few decades, Breuer’s office designed several more houses for the Stillmans, including a vacation cottage on Cape Cod. Stillman’s colleagues at the Torin Manufacturing Company became clients, and the company built factories to Breuer’s designs as it expanded around the world. Breuer was becoming a designer of a full range of modern buildings, but also an architect of growing networks.

Themostdaringofallhishousedesigns was built for his own family in the late

’40s in New Canaan, Connecticut, then a magnet suburb for the Harvard-trained modernist architects setting up in the New York market. Here, the system of using triple layers of plywood to form a strong envelope over a truss-like woodenstudboxframewascarriedtothe ultimate as Breuer cantilevered his house off a stone base and then, in turn, cantilevered a terrace balcony off the living room end. (The levitation was shortlived, as already during construction, the sagging terrace threatened collapse and had to be shored up by a stone wall.)

Breuer considered multi-ply plywood to be akin to concrete, so there is a continuity of experimentation between the New Canaan house and the great ’50s and ’60s buildings of hollowed-out concrete that he would cantilever over the landscape— like the IBM headquarters at La Gaude, France—or the city, as for the Whitney.

Breuer’s career changed abruptly in 1952-53 with the sudden success in two

completely unexpected undertakings for large-scale institutional buildings: UNESCOinParisandSt.John’sAbbeyin Minnesota. These commissions shifted his practice forever, requiring a new life of air travel, more associates and consulting engineers to support his search for new structural possibilities. The quest for sculpturally expressive monumental forms that could embrace serial normality and the heroics of modern engineering became the major theme of Breuer’sworkforthenextthreedecades.

In Paris, the powerful canted forms of the UNESCO Conference Building, built with plaited concrete, played off the glazed curtain wall of the Y-shaped Secretariat, which was raised on muscular concrete pilotis. The same could be said of the contrast between the similarly formed Abbey Church, with its sculptural bell banner and the repetitive cells of the nearby monastery block and the student residence halls on campus.

“Buildings no longer rest on the ground,” Breuer explained in a 1963 lecture. “They are cantilevered from the ground up. The structure is no longer a pile—however ingenious and beautiful— it is very much like a tree.” He concluded by advocating for an architecture in which sculptural form and its space-making capabilities would lead the modern movement beyond its earlier obsession with new materials. True to his word, in hisuseofmarbleatSt.John’sortherichly patterned granite of the Whitney—his next headline-grabbing commission—he sought to bring modern architecture into a realm of symbolic expression that had been reserved for older styles. “Although not resting on lions or acanthus leaves,” he noted, “space itself is again sculpture into which one enters.”

Perhaps no building better exemplifies Breuer’s newfound aesthetic of “heavy lightness” than the Whitney. In

June1963,afteronlyeightyearsinabuilding designed for them by Philip Johnson on West 54th Street—on land donated by MoMA and adjacent to its own expanding campus—the Whitney’s trustees decided to get out from under their more famous neighbor (and occasional rival) and establish a new presence for American art on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, the heart of the postwar gallery scene. Selected over a host of well-known architects, including I.M. Pei, Louis Kahn and Johnson, Breuer quickly appreciated the challenges of the commission and, after a weekend at home in New Canaan, returned with his design for the inverted ziggurat. The museum would be clad in flame-treated granite and would loom out dramatically over the corner of Madison Avenue and East 75th Street. Without violating any building or zoning codes, Breuer took the famous setback skyscrapers of the 1920s and 1930s—as well as the whitebrick apartment houses then sprouting

up everywhere on the East Side—and turned them upside down. His solution was decidedly singular but also clearly a piece of New York’s urban fabric.

“What should a museum look like, a museum in Manhattan?” Breuer began his presentation to the trustees in November 1963. “It is easier to say first what it should not look like. It should not look like a business or office building, nor should it look like a place of light entertainment. Its forms and its materials should have identity and weight… in the midst of the dynamic jungle of our colorful city. It should be an independent and self-relying unit exposed to history, and at the same time it should have a visual connection to the street, as it deems to be the housing for 20th-century art. It should transform the vitality of the street into the sincerity and profundity of art.”

To enter the building, one takes a sidewalk via a bridge, announced by a cantilevered canopy, under the overhang and into a lobby with a gridded ceiling of circular lighting fixtures. As much as his design resonated with the emerging minimalist scene in 1960s sculpture, Breuer was thinking largely in terms of the stakes of history and symbolism that had entered the internal critique of modernism with the debates on monumentality inthemid-1940s.“Today’sstructureinits most expressive form is hollow below and substantial on top—just the reverse of the pyramid. It represents a new epoch in the history of man, the realization of his oldest ambitions: the defeat of gravity,” Breuer told his friend Peter Blake in 1964. With exposed bush-hammered concrete fin walls to separate off his granite-faced, cantilevered sculpture, Breuer cut out the urban equivalent of the white box gallery so beloved by his contemporary minimalists and asserted the singularity of culture, protecting art from the nearby commercial world and conveying a sense of remove from the quotidian.

Working with the structural engineer Paul Weidlinger, Breuer lifted his cantilevered mass above a glazed, recessed ground floor—the world of the sidewalk and the sales counter on axis with the entrance—connected by a fixed-in-place drawbridge. He inserted great panes

of glass into the recessed stair tower, providing changing vistas of Madison Avenue with each switchback. These were the first in a series of staccato framed views that find their echo inside in the mysterious trapezoidal “eyelid” windows freely attached, like ornamental broaches, on the blocky exterior. To keep their immense planes of glass from conflicting with the galleries’ reliance on artificial light, the trapezoids angle outward, creating uncanny vignettes of the city while avoiding any capricious play of light in the inner sanctuary. Breuer thus created a building of deliberately contrasting experiences: a lobby based on a new ideal of flow and spatial excitement, in which architecture, large-scale public sculpture and the city converse, and then, above, inwardly focused gallery floors. The largest uninterrupted expanse and loftiest ceilings were reserved for the fourth-floor gallery: a full 118 feet of clear space before the installation of the movable system of panels. Here is the largest of Breuer’s trapezoidal windows, the only one on the Madison Avenue front, framing a view of New York as an unfinished work of urban art.

The building was a capstone of one of the most productive, sculptural and inventive moments of Breuer’s career, and an instant attraction. Perhaps cartoonist Alan Dunn captured the sense of charmed bewilderment best in The New Yorker: Two women walking by wonder aloud, “Why can’t someone design a museum that doesn’t have to be explained?” Indeed, Dunn would repeatedly poke fun at both the Whitney and the Guggenheim as the two heralded a period in which museum buildings wouldbecomemoreandmoredistinctive, a trend that continues today.

It might seem counterintuitive to have selected Herzog & de Meuron to restore both the exquisite material paletteandthecomplexinterplaybetween the bustling lobby and the contemplative galleries. Some of the most sculpturally and spatially exciting museum buildings of the last three decades have been the firm’s creations, from the Sammlung Goetz, opened in Munich in 1992, to the

four-year-old M+ in Hong Kong. They are, in all this work, architects of strong form and complex spatial section to rival Breuer. But as architects who restore, they have shown a broad range of aesthetic expression, from the late Victorian interiors of the Park Avenue Armory to the bluestone floors, egg-crate suspended ceiling and bush-hammered concrete that are Breuer’s signature at the Whitney. “It was one of the buildings I made a point to visit as a young architect,” says Herzog & de Meuron’s Walschap. “Even then I was surprised by how different it felt in context—its geometry and materiality, the composition of its windows and especially the sunken garden, which creates this unexpected piece of public space within the New York streetscape.” Theirs is a light touch in refreshing that material palette, already so well restored for the Metropolitan Museum’s temporary use of the building, adding primarily a new lighting scheme in the framework of the egg-crate ceiling to suit the much more diverse and rapidly changing display needs of auction exhibitions and showrooms on the three gallery floors. The other major new lighting is under the bridge’s canopy to create a livelier street presence for a building that will have much greater evening life, not least because of a new restaurant on the lower level by New York designers and restaurateurs Robin Standefer and Stephen Alesch, of the firm Roman and Williams. Perhapsmostexcitinginthisnewchapter of the building’s life is the animation that Sotheby’s will bring to the building and for which the architects have adapted it. The lobby will feature new displays, with Breuer’s beautiful benches cleverly adapted to display cases and the often-overlooked lofty space beyond the famous elevators given new life as a feature gallery. What the work promises is that Breuer’s building has neither looked so good, nor been so animated in its activity, since the days of the Whitney’s first use of its new architectural masterpiece in the 1960s. •

Partially adapted from Barry Bergdoll’s 2016 essay “Marcel Breuer: Bauhaus Tradition, Brutalist Invention” from the Metropolitan Museum Bulletin.

On a hazy Friday afternoon, fashion designer Nili Lotan’s Crotonon-Hudson kitchen smells of butter, sugar and toasting almonds. The galley-style space is just wide enough for Lotan, dressed in a denim shirt, barrel-leg jeans and flip-flops, to extract a baking sheet from the oven, dust it with powdered sugar and pile hot cookies onto a plate. She heads to the dining table, free of clutter like the rest of the compact house, which was designed in 1953 by Marcel Breuer. Over a batch of her mother’s almond crescents, Lotan points out some of the moves she’s come to understandasthearchitect’ssignatures— starting with the freestanding fireplace, companionably close to a built-in sofa, which rises from the bluestone floor and disappears into a slatted-cypress ceiling. It lends the room a weight that seems to anchor the house to its dramatic site, on a promontory high above the Hudson River,about40milesnorthofManhattan.

In 2020, when Lotan first came up to Croton in search of a weekend escape from her home in Tribeca, she had an instant reaction to the view. “It took me back to my childhood,” she recalls. “The water of the Mediterranean was right in front of me again.”

Lotan grew up in Israel, where her father developed real estate along the