Oliver Barker

Emma Baker

by Dawn Ades

Oliver Barker

Emma Baker

by Dawn Ades

BY OLIVER BARKER CHAIRMAN, SOTHEBY’S EUROPE

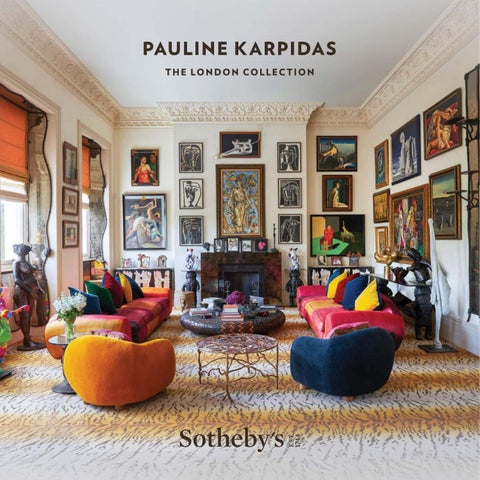

For more than 25 years, I have been fortunate to observe Pauline Karpidas and the qualities that mark her as a collector of rare distinction—none more striking than her profound well of loyalty. It is a gift she extends to her collaborators, an unwavering quality that has won her the company and friendship of many of the great art world figures of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, with whom she has cultivated deep connections and championed careers with insight and steadfast dedication. It is no overstatement to recognise Pauline as one of the most respected collectors today and it has been a privilege to enjoy our connection, witnessing the passion, intellect, and energy that have shaped her exceptional homes and, in truth, the cultural landscape of our time.

In 2023, Sotheby’s Paris offered the collection from Pauline’s legendary retreat on the Greek island of Hydra, an event that transported visitors to the ancient place where she indulged her love of the contemporary. With immense pride, we now present the collection from Pauline’s London residence, an apartment that overlooked Hyde Park—a sanctuary where she gathered the objects that trained her instinctive eye, with walls lined with masterpieces from the Surrealists and Pop Art pioneers to icons of contemporary design.

More than simply revealing her collecting journey, however, the London auctions will mark a celebration of Pauline’s unapologetically bold vision and kaleidoscopic taste, offering the most tantalising glimpse into the wonder and joy of her world. The essays contained herein by Emma Baker, Dawn Ades, and Alyce Mahon trace an exceptional collecting career from its formative years, examining Pauline’s

unique significance in the long legacy of Surrealist collectors, and pay testament to the remarkable works she brought into living dialogue.

My first encounter with Pauline came in the mid1990s, through an introduction by the late Michel Strauss, the head of Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern Art department for over four decades—during which he gave me my first job—and the man who served as Pauline’s contact in the business. It was a time before the dispatch of WhatsApp messages became a channel of communication with collectors, a time, as she once described to me, “when collecting art was still a conversation and an intellectual journey.”

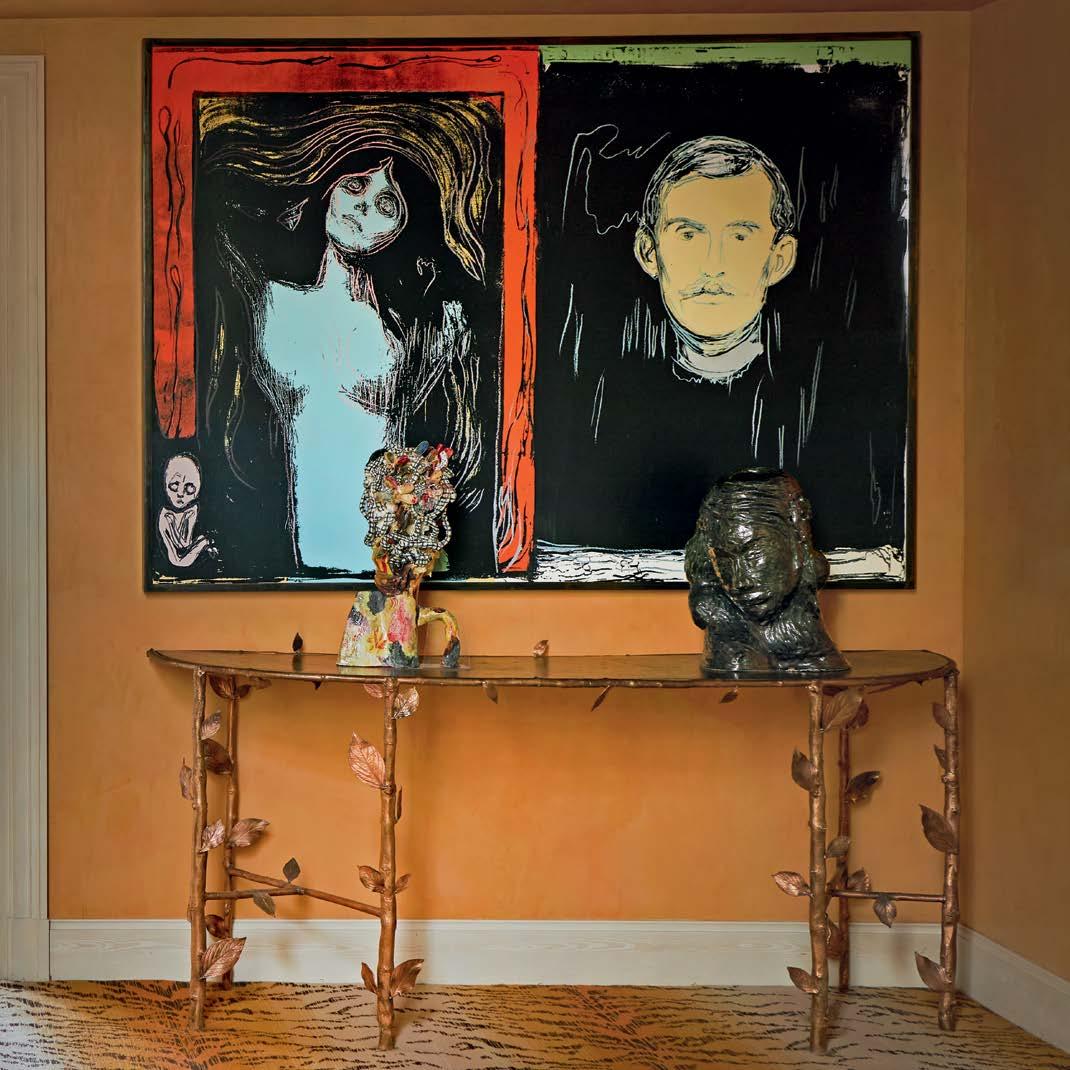

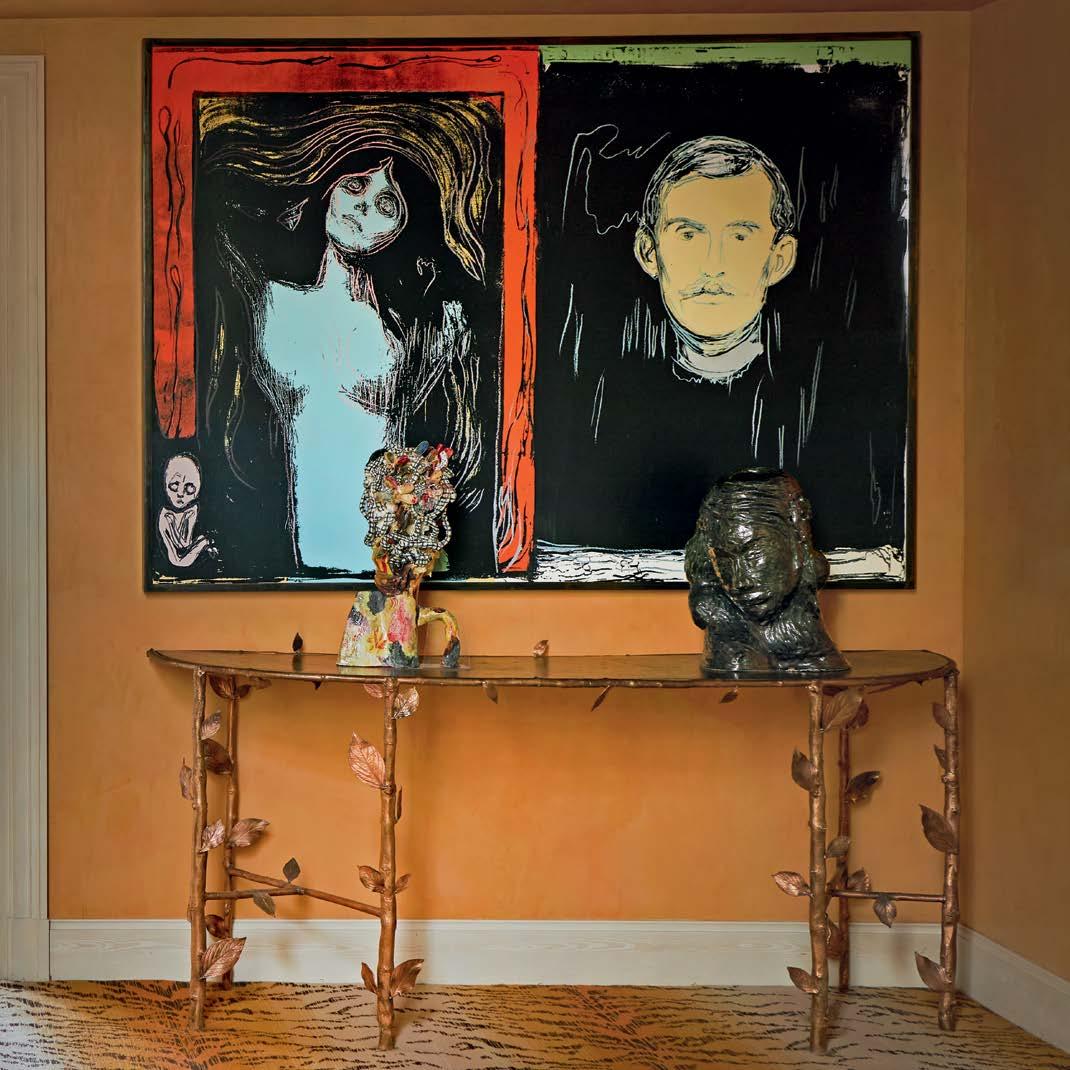

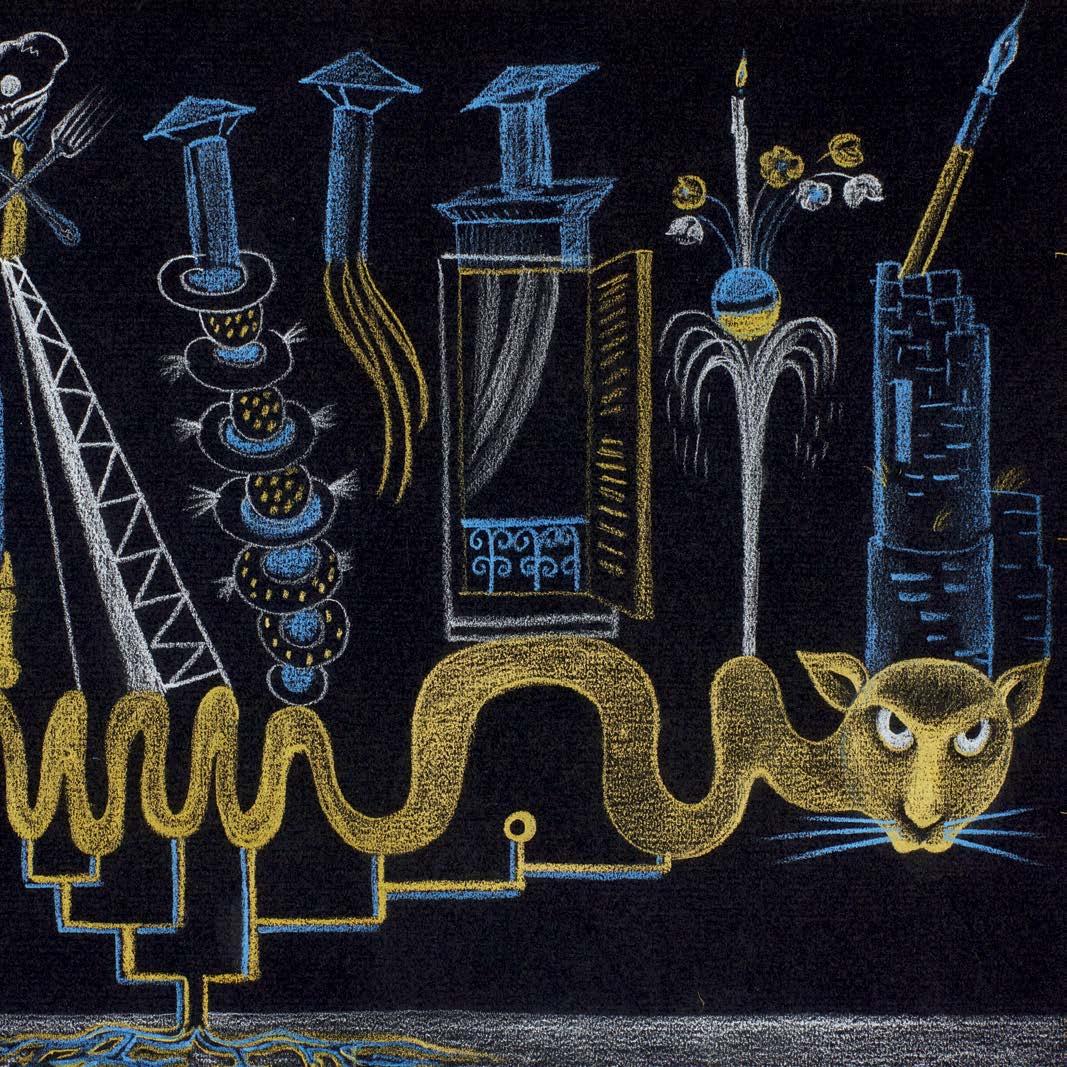

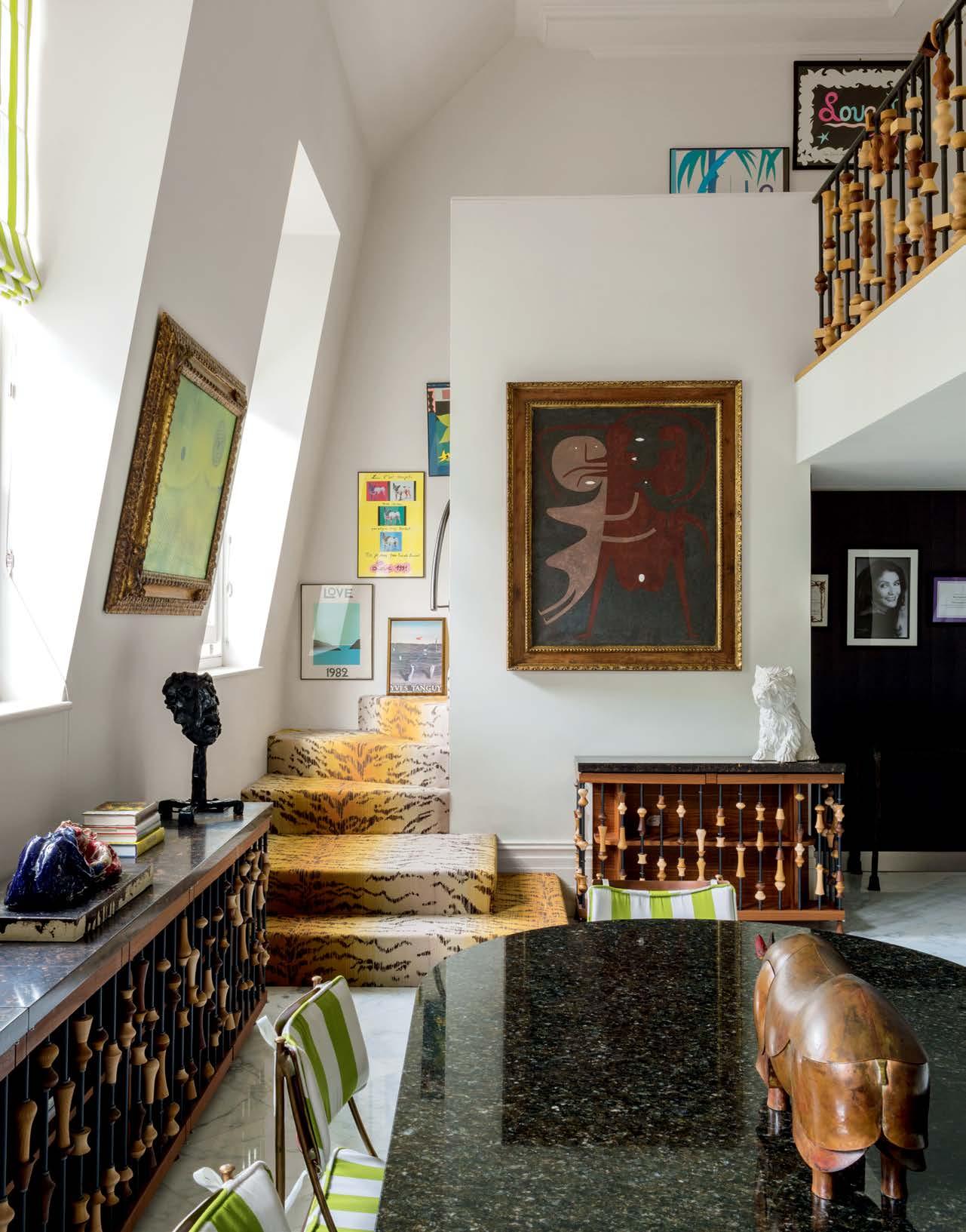

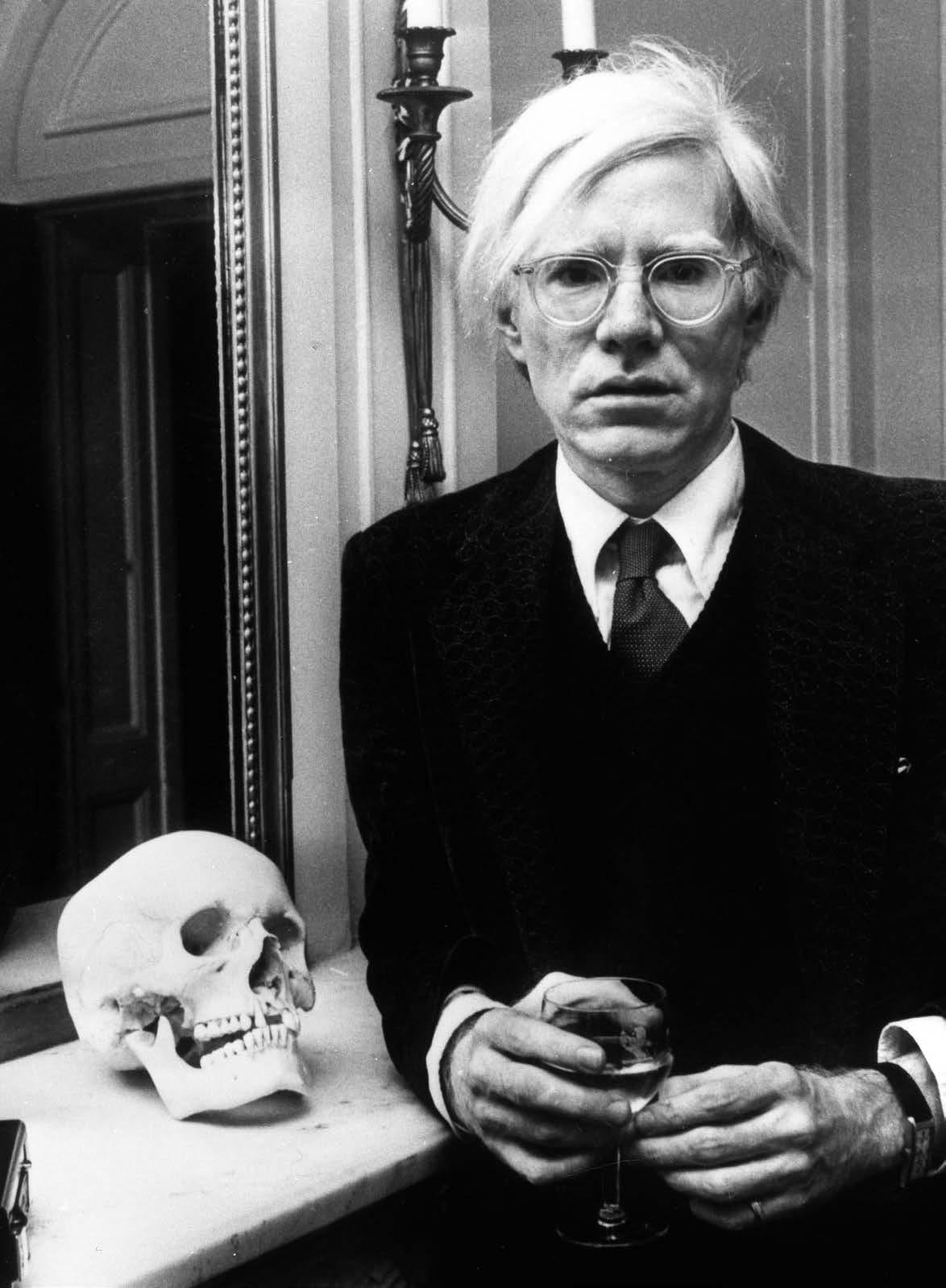

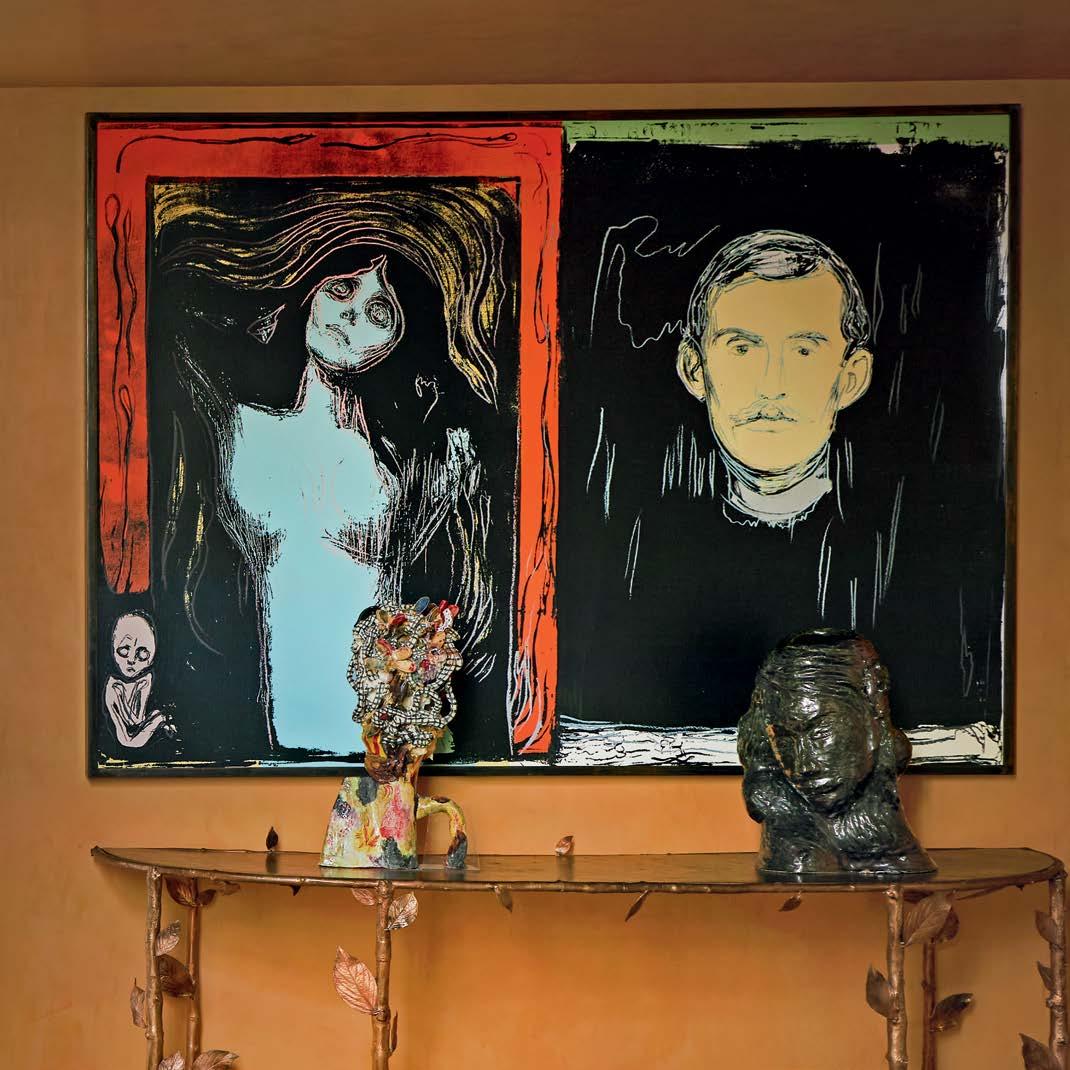

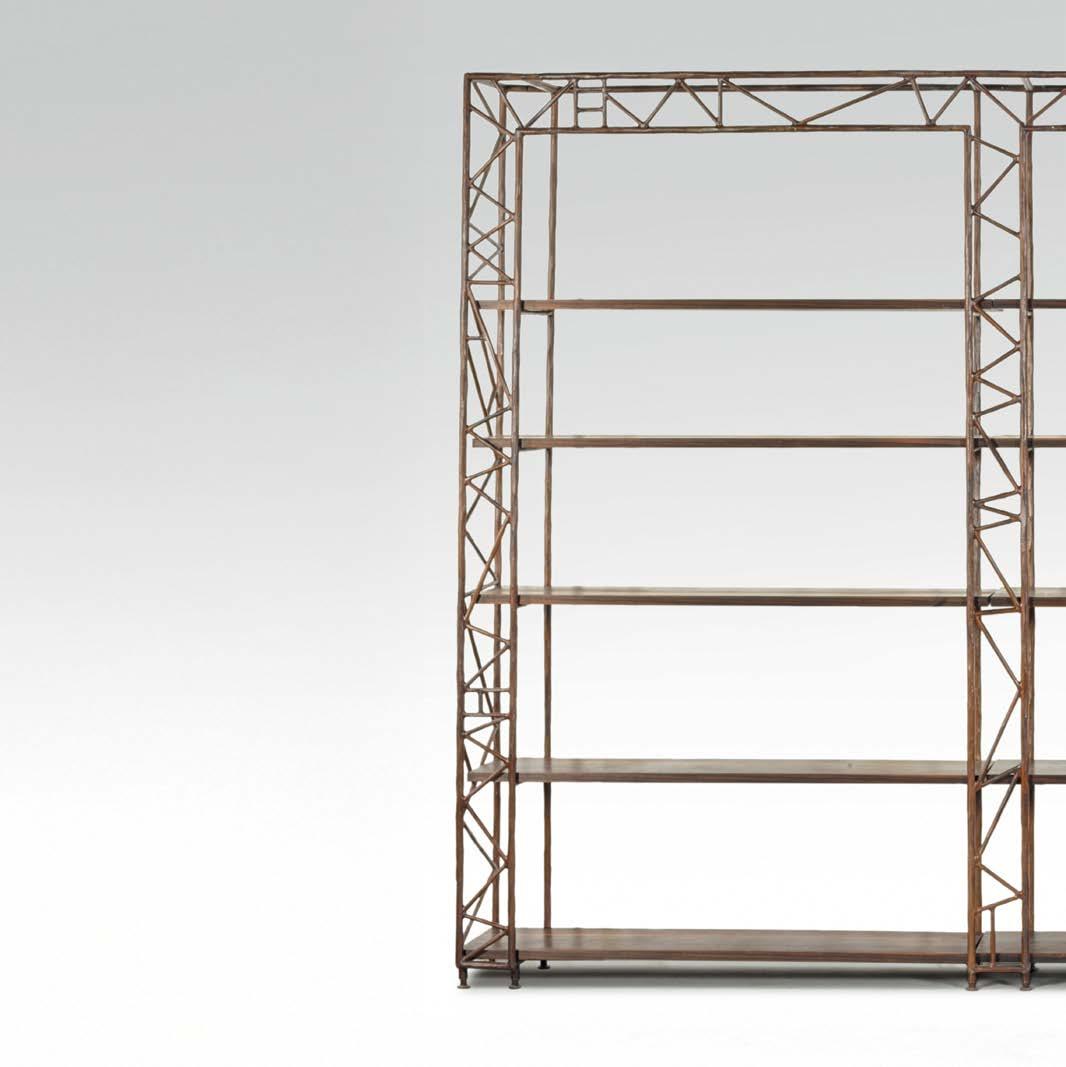

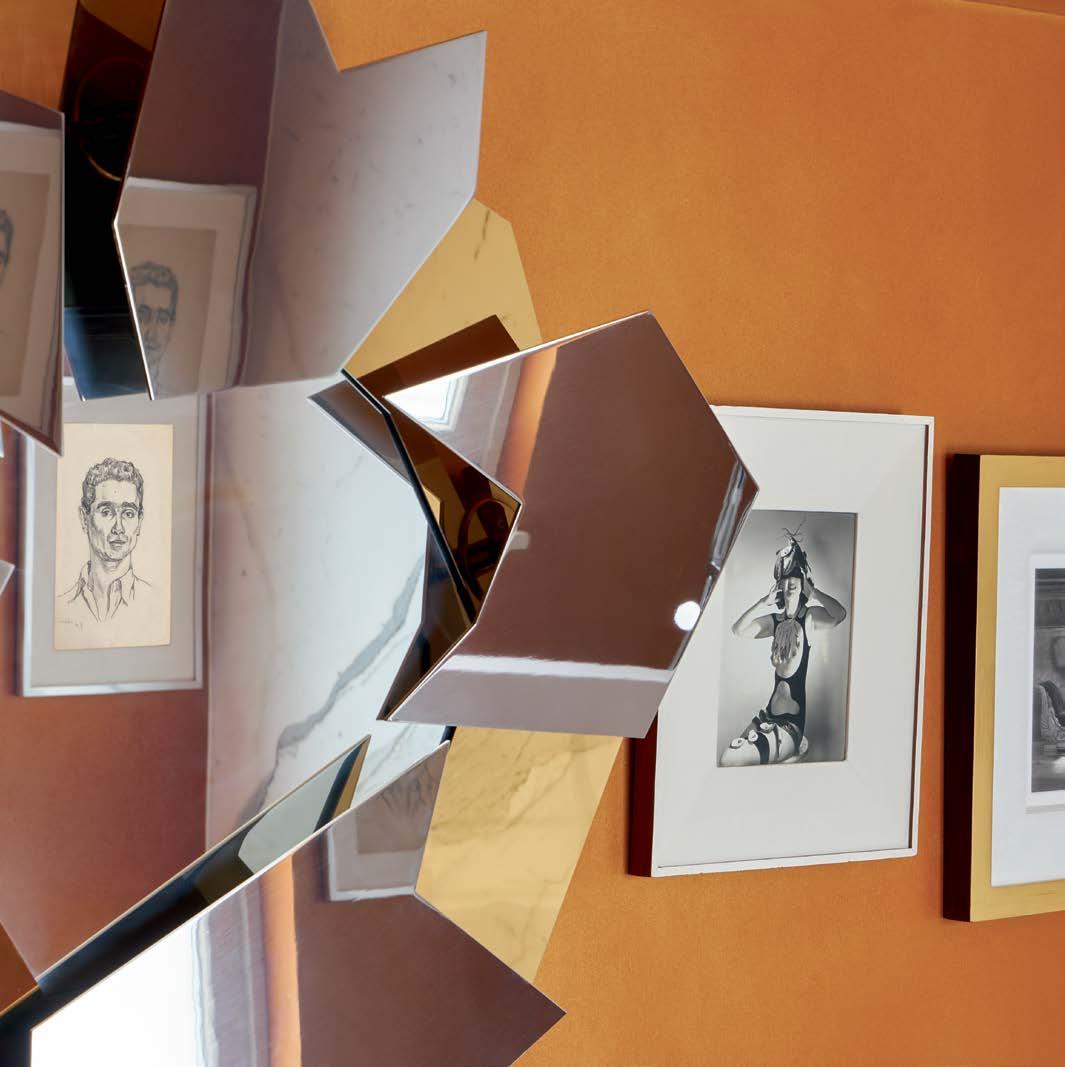

The moment I first entered Pauline’s apartment, I was awe-struck by the singular atmosphere of the space: the home itself a living work of art where Surrealist masterpieces rubbed shoulders with Les Lalanne sculptures and Andy Warhol’s late-career Pop icons, all set against interiors by David Gill, Francis Sultana, and Jacques Grange, including the iconic animal print carpet. Stepping inside felt like stepping into another world—a Gesamtkunstwerk of Surrealist imagination and postmodern bravura. It reflected her innate ability to collect objects of the highest quality, and to curate an immersive world where each artwork amplifies the next. This was a heady space filled with stories; a modern-day salon akin to that of Gertrude Stein, where collecting and friendships with some of the art world cognoscenti of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries were made manifest amongst objects previously owned by luminaries of the pre-war period. By definition, it was a true monument to a life of passion lived in the pursuit of great beauty and intellectual endeavour.

“ULTIMATELY,

THE LIFE I’VE HAD IS A VERY RARE LIFE. I REALISE HOW FORTUNATE I HAVE BEEN TO HAVE HAD SO MANY WONDERFUL PEOPLE AROUND ME WHO TAUGHT ME ABOUT ART HISTORY, COUTURE, JEWELLERY, DESIGN, AND THE WAY TO SEE THE WORLD THROUGH THE EYES OF A CONTEMPORARY ARTIST. FOR ALL OF THIS I AM ETERNALLY GRATEFUL.”

PAULINE KARPIDAS

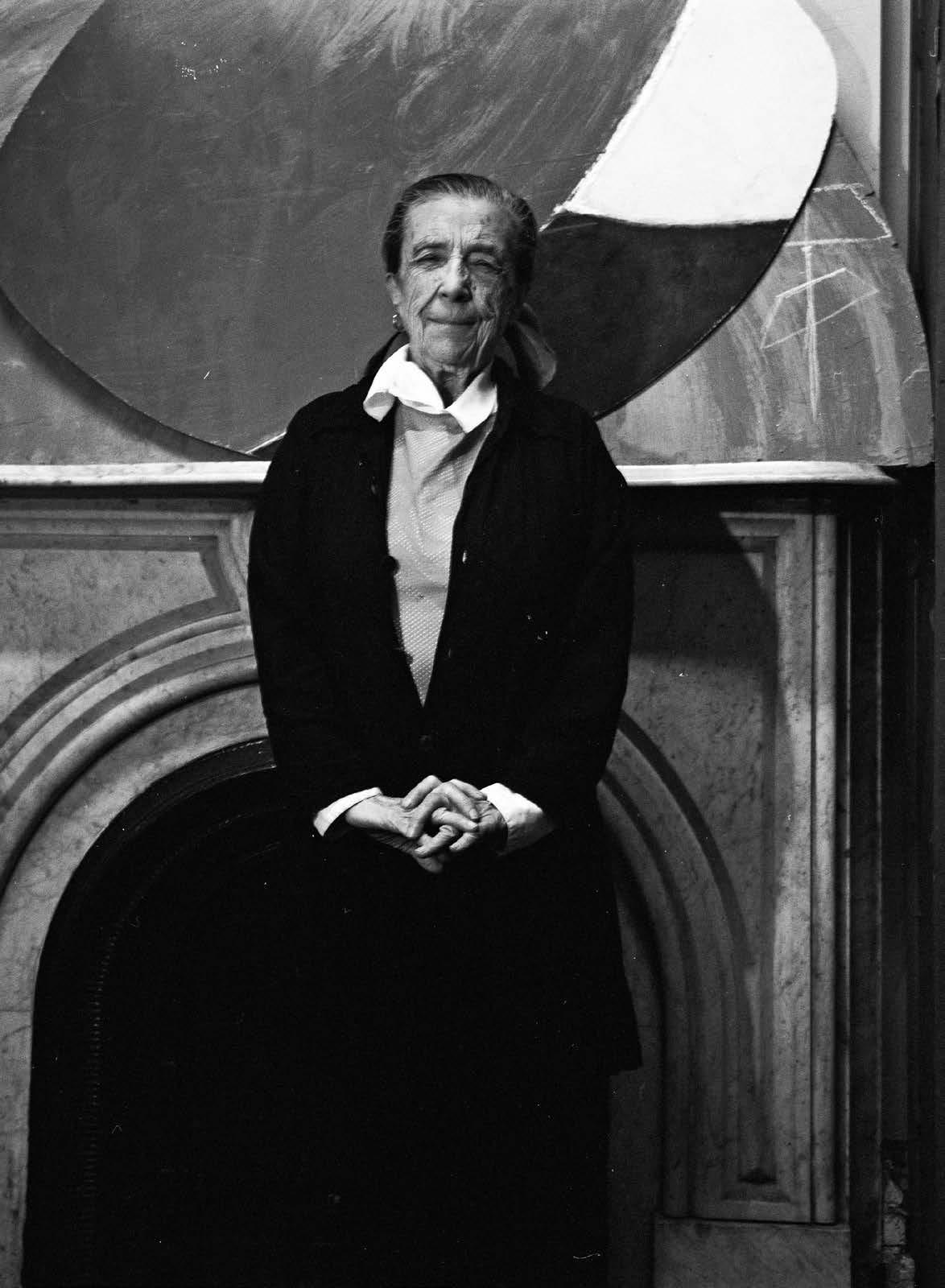

Pauline belongs firmly in the tradition of the Grand Dame collectors—visionary patrons such as Gertrude Stein, Peggy Guggenheim, and Dominique de Menil—whose daring shaped the cultural imagination of their eras. From her beginnings in Manchester to her cosmopolitan life in Athens, the creative ferment of 1970s London, and her regular visits to New York, she has always sought out the pulse of contemporary culture.

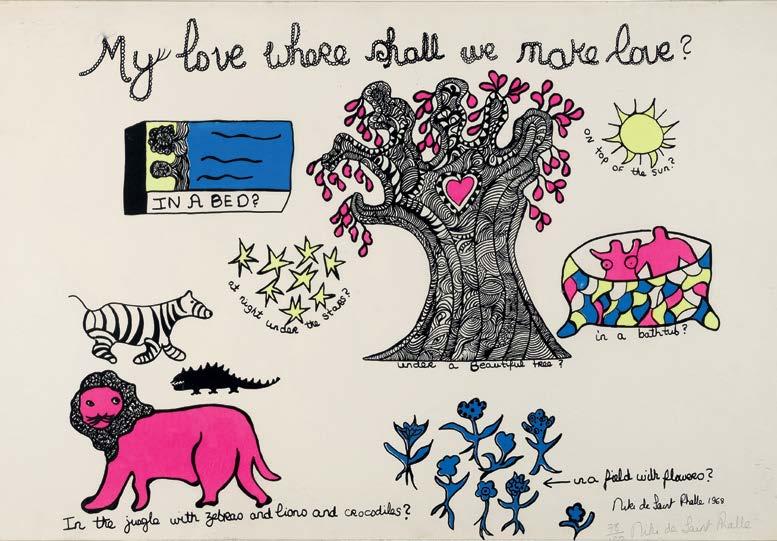

Her evolution into the collector we honour today was guided by a circle of artists and gallerists— none more significant than Alexander Iolas. His counsel helped her refine her eye and define her distinctive path. It was in 1976 that Pauline’s passion for Surrealism was born, with acquisitions of works such as Magritte’s La Statue Volante, courtesy of Iolas, anchoring what would become a collection of extraordinary range and coherence. The spirit of Alexander Iolas—patron to many of the artists she collected in this era, from de Saint Phalle and

Picabia to Magritte and Fontana—threads through the narrative, reinforcing her deep ties to the avant-garde and her unwavering commitment to both excellence and legacy.

Pauline’s collection is distinguished not only by the calibre of individual works but by the intelligence of their dialogue. Many pieces carry distinguished provenance—having passed through the hands of Edward James, Julien Levy, Hélène Anavi, and the Picasso family—yet each was chosen as part of a larger conversation across time and style. The unity of the collection is undeniably its greatest triumph. It is the

embodiment of harmony between art, environment, and intellect—a seamless fusion of visual brilliance and philosophical depth. The dialogue between objects is not limited to painting and sculpture; it extends through the very bones of her home.

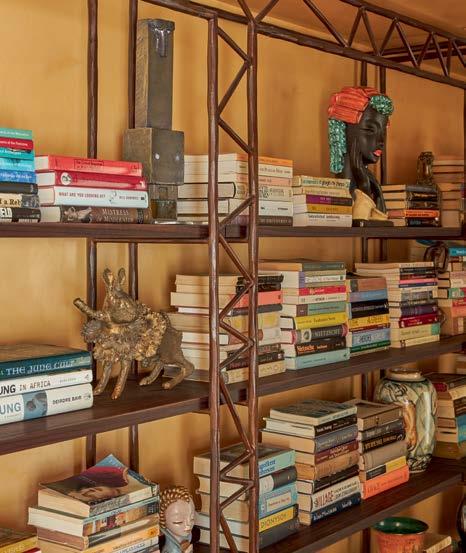

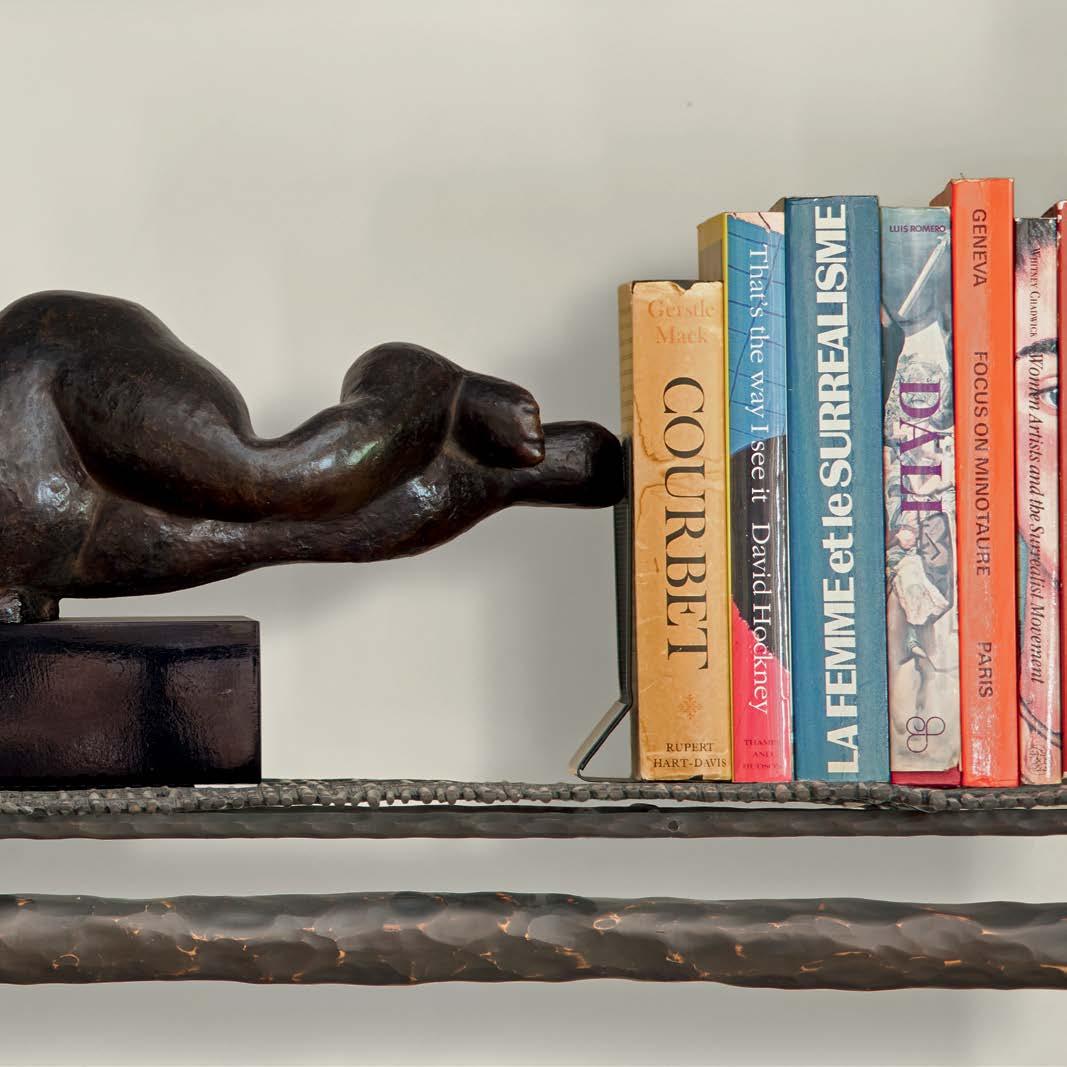

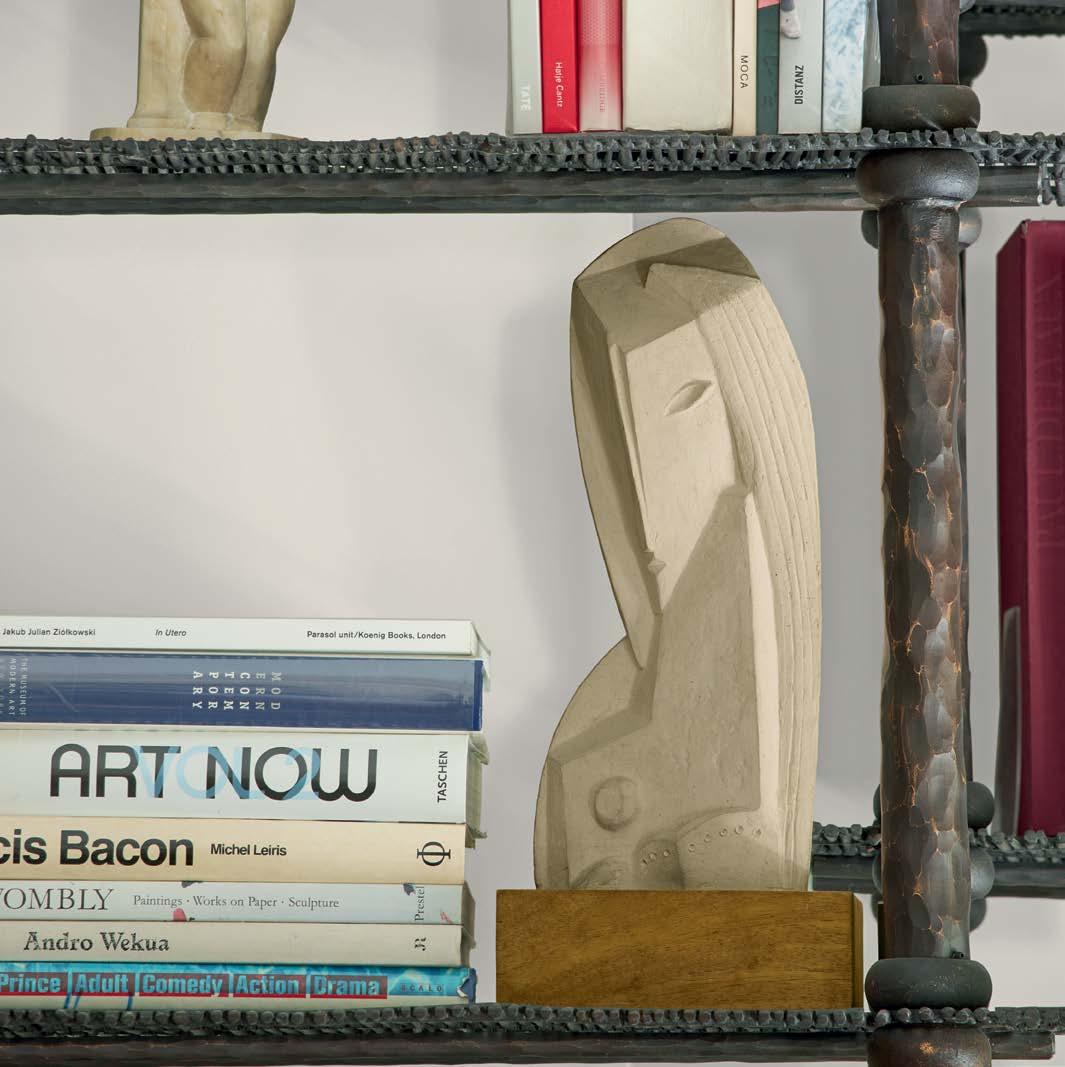

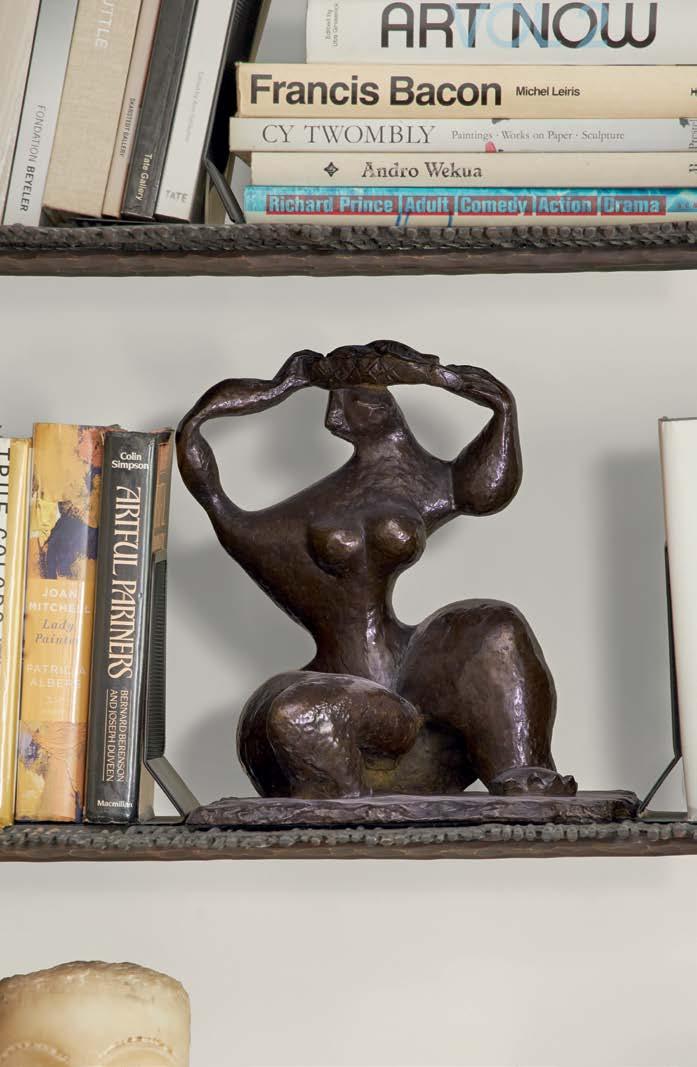

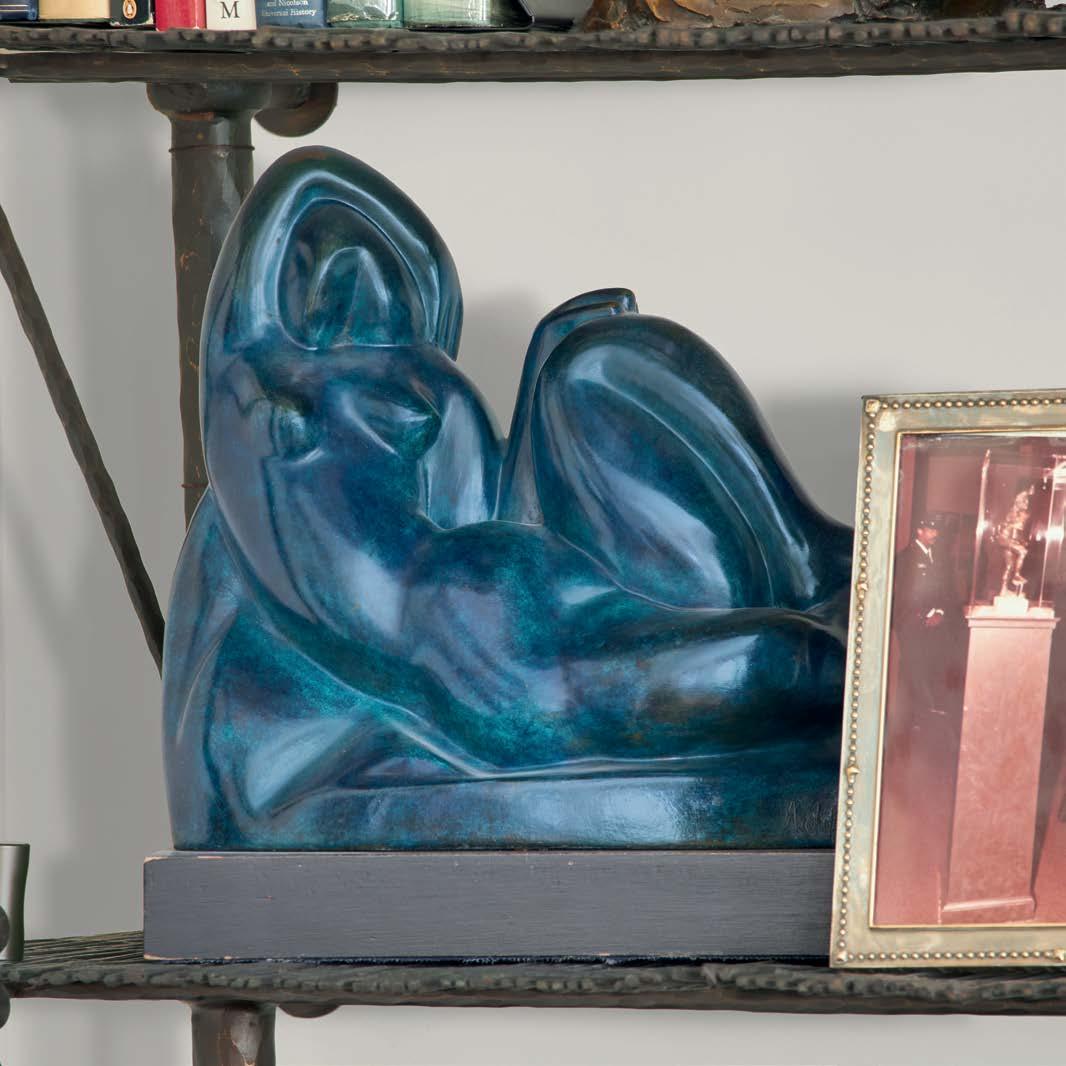

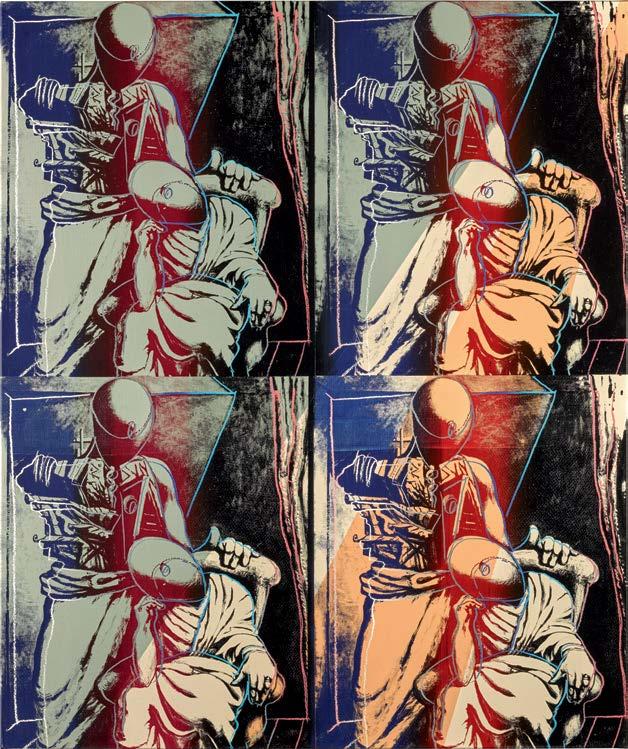

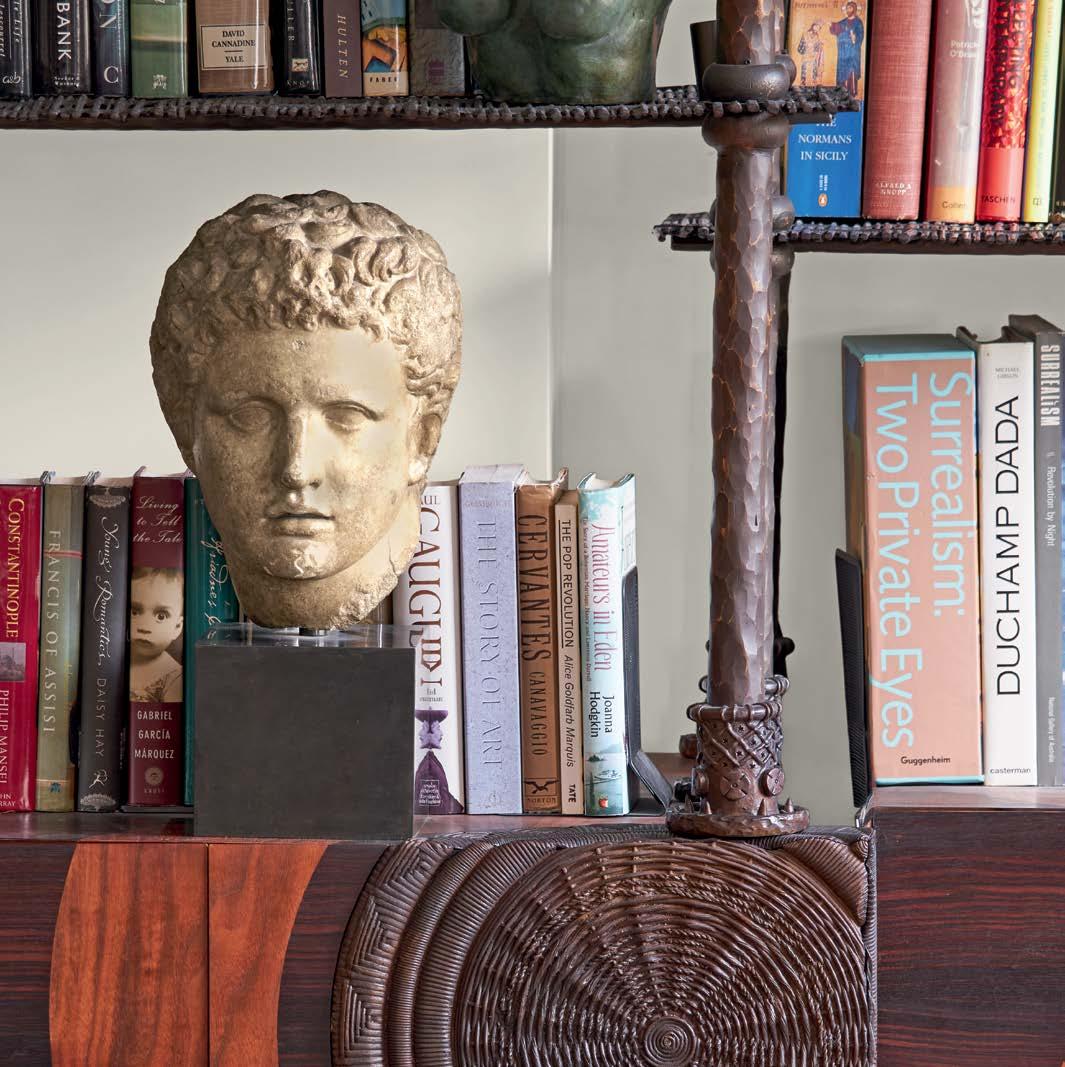

This holistic aesthetic vision is underscored by an extraordinary library of monograph publications, texts on Jungian psychoanalysis, and philosophy— evidence of the cerebral framework underpinning Pauline’s collecting. Surrealist masterpieces by Óscar Domínguez, Leonora Carrington, Yves Tanguy, and Victor Brauner speak to this fascination with the subconscious, mirroring both the dreamscapes found in her books and her own lifelong fascination with inner worlds, and indeed the revelations of our dreams. Meanwhile, the presence of Warhol’s dreamlike de Chirico appropriations in her bedroom reinforces the extreme care taken in her curatorial choices.

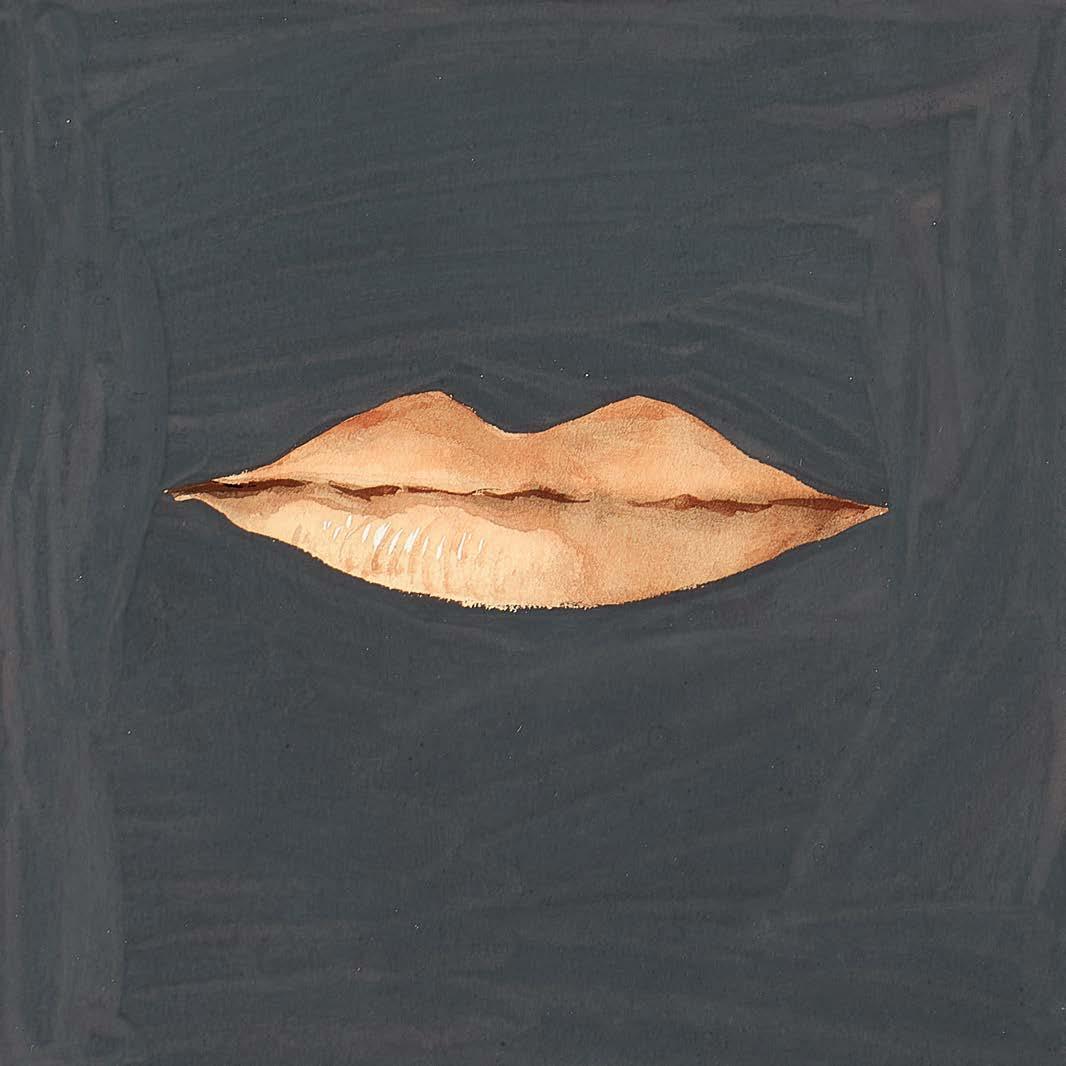

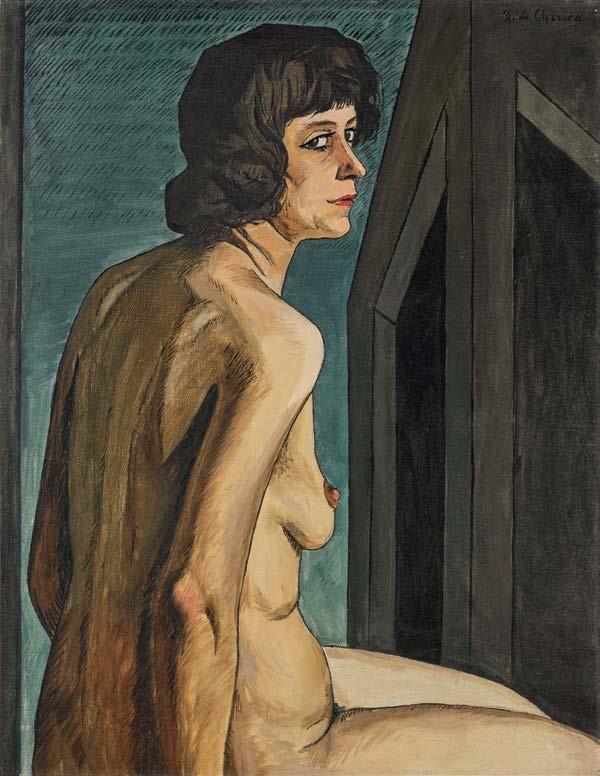

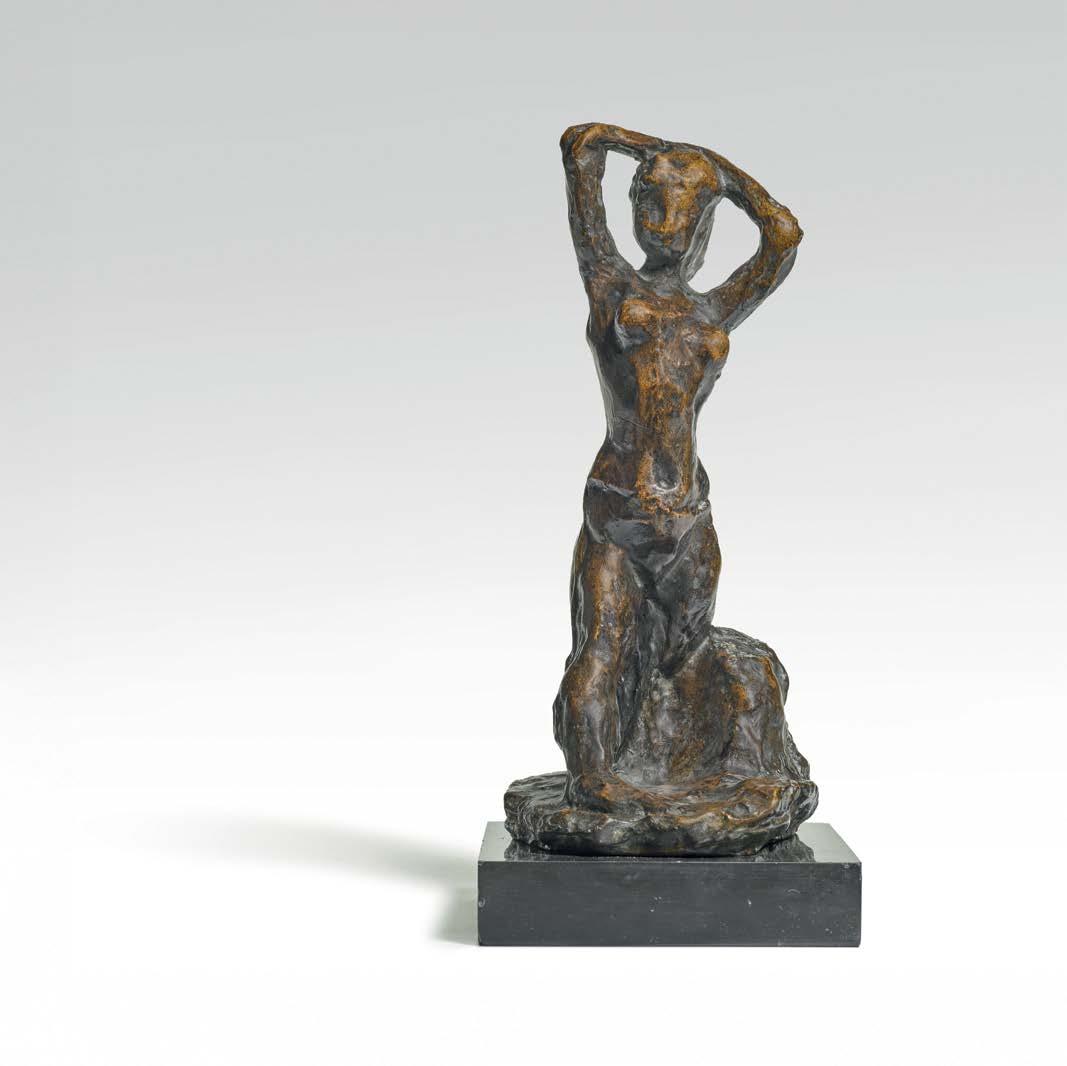

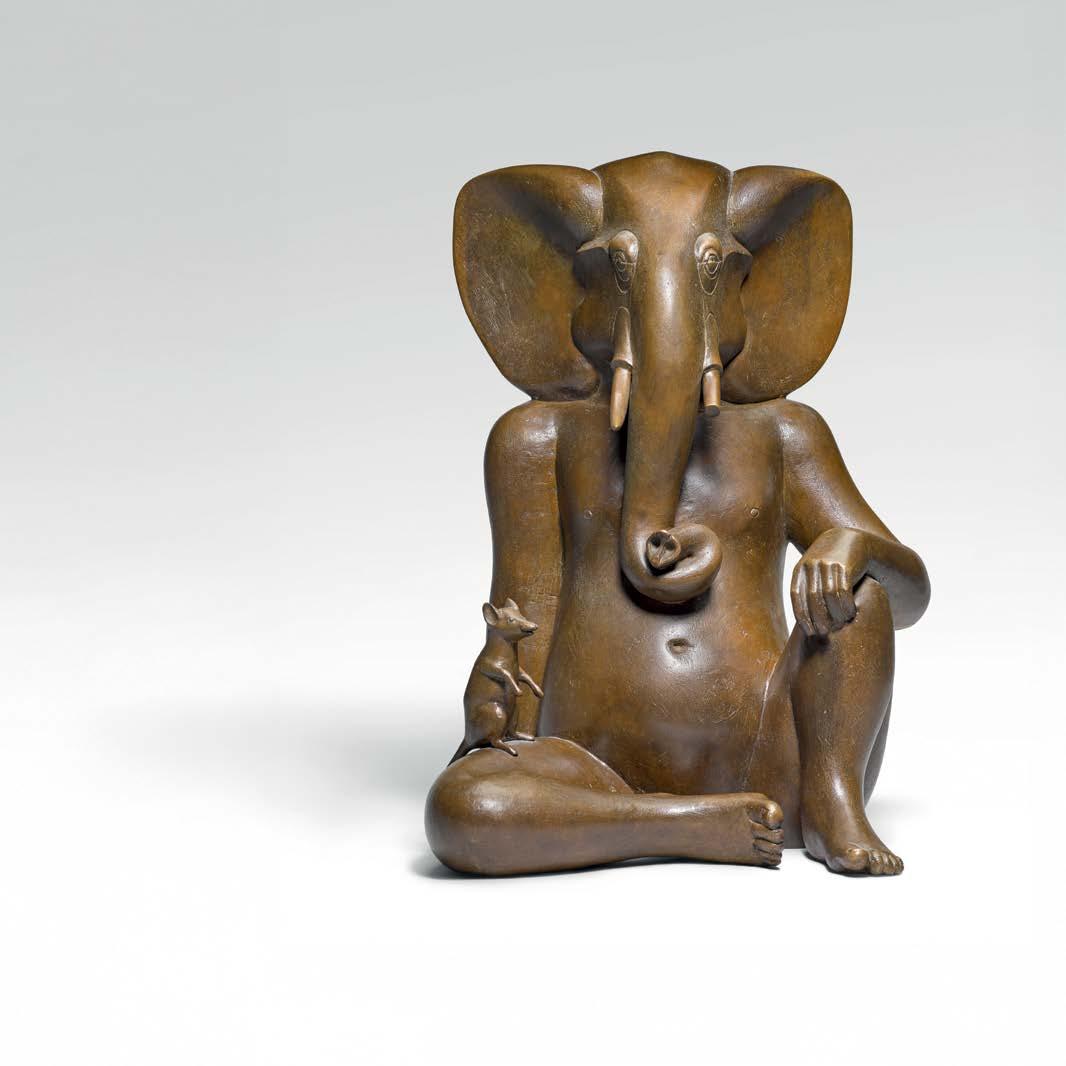

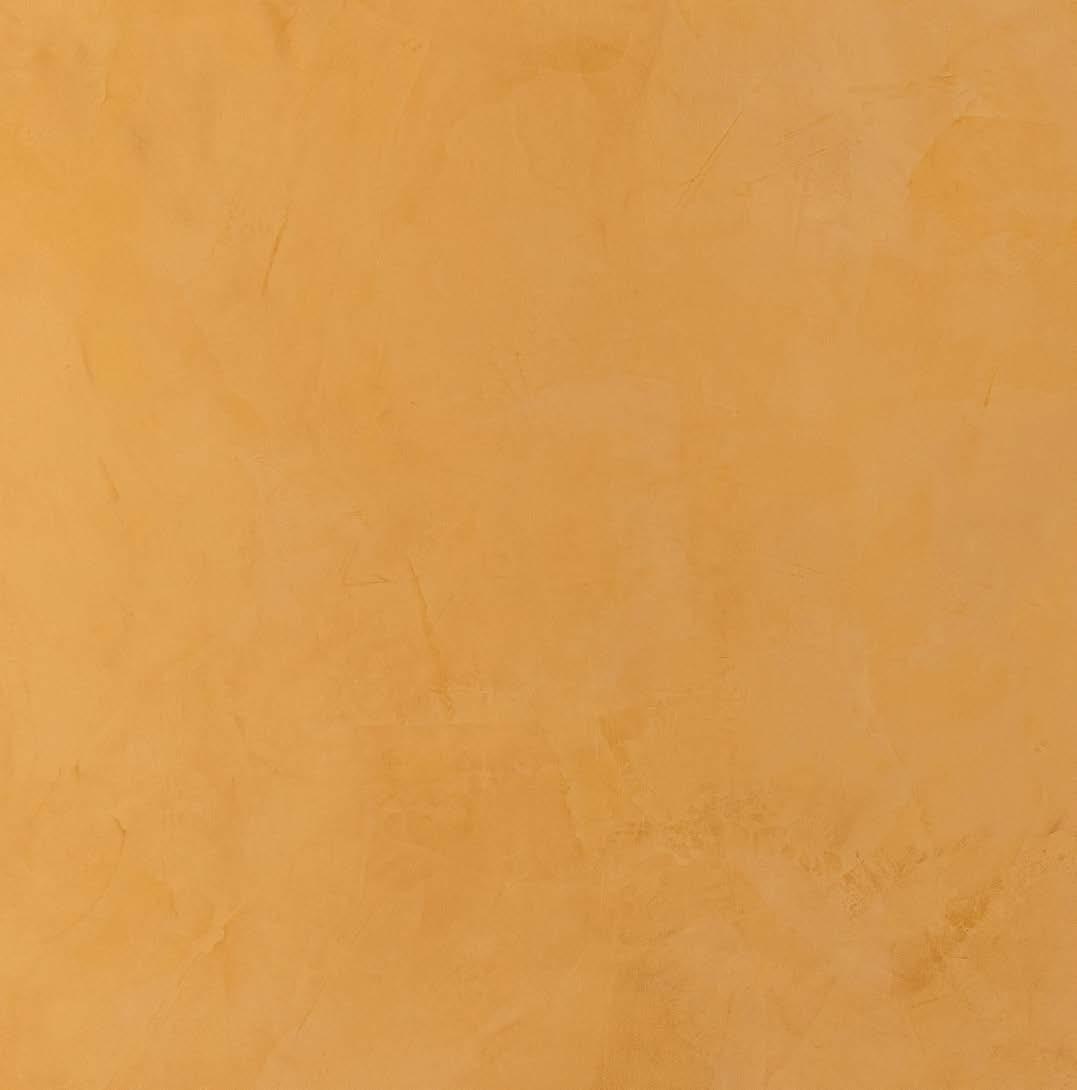

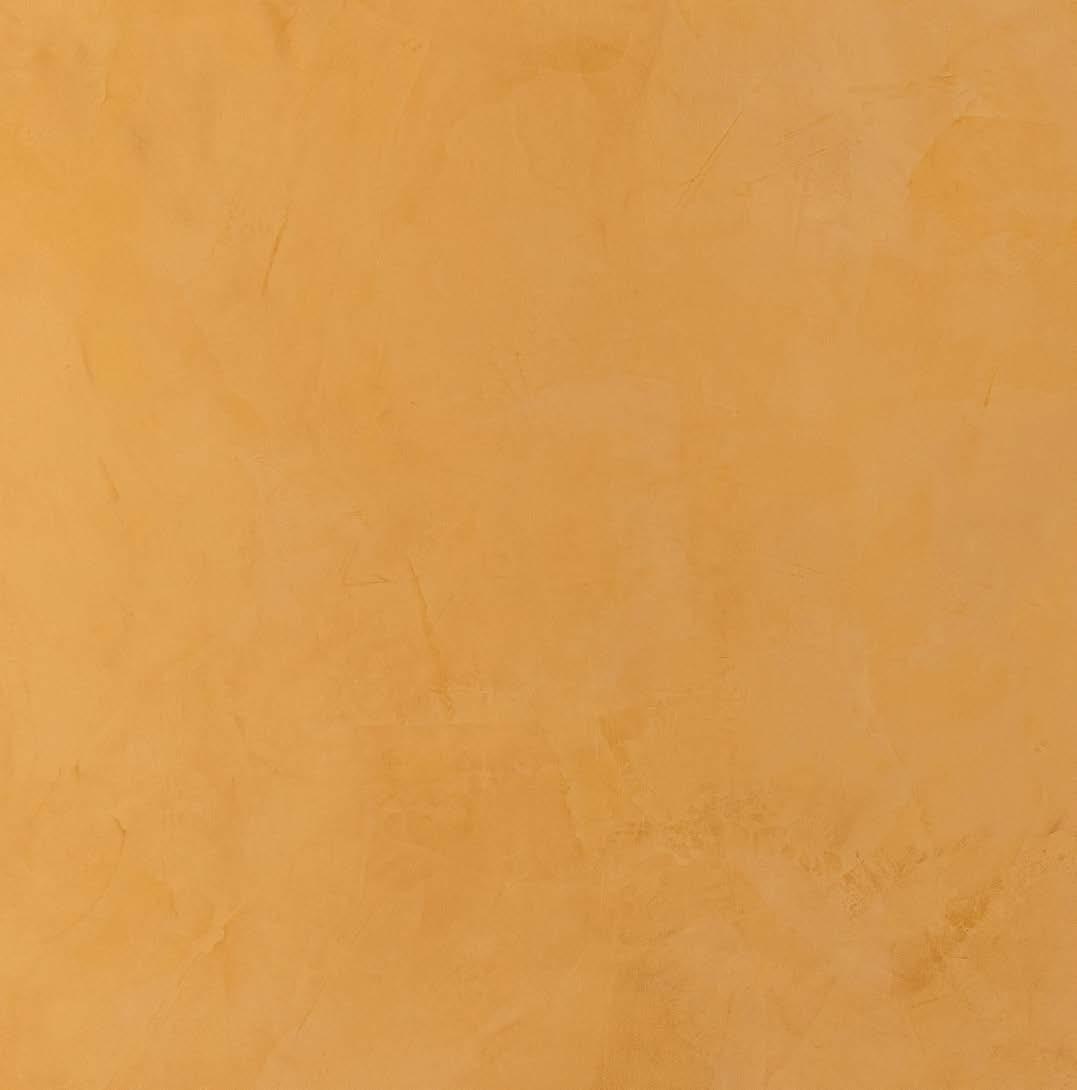

The female nude reappears in many of the most remarkable images of Pauline’s collection, notably explored by Picabia, Dalí, and de Chirico. Her many sculptures also take the female form as their starting point: from Magritte and Giacometti to the Lalanne, Bourgeois, and Warren. In this way, the collection embraces the motif for both its historical gravitas and contemporary energy. Pauline’s eye for harmony was evident too in even the smallest details, such as the salon blinds meticulously crafted by Sultana to cast a golden light, imbuing the space with the same radiance she brought to each acquisition.

The release of a collection of this calibre inevitably stirs reflection. Several years ago, before we began planning this series of auctions together, Pauline told me with characteristic humility: “It doesn’t feel like mine—I feel removed from it. I feel I’ve just been a curator of this … it’s been a long journey, it’s been a career and an education.” In that sentiment lies the essence of a great collector. She saw herself not as an owner but as a steward, and the collection was never static. It evolved over fifty years, becoming an extension of a life spent in pursuit of meaning and connection.

Now, as these works stand at the beginning of new chapters in other collections, they do so not as isolated treasures but as echoes of a singular, visionary whole. Her legacy lives on in the spirit of inquiry and dedication that drew each piece into her orbit. Few have built a collection of such consistent distinction.

The journey she undertook was all-consuming: the reading, the encounters with artists, the counsel she sought, and her willingness to immerse herself in the world of ideas and images. That devotion—that constant state of becoming —is what makes Pauline not merely a collector but a patron of the arts in the highest sense.

On behalf of all of us at Sotheby’s, I am enormously grateful to Pauline and her family for entrusting us with her extraordinary legacy—an expression of the loyalty we have come to cherish. This sale is not only a celebration of a lifetime of collecting but a heartfelt tribute to a woman whose profound influence as a patron of the arts will resonate for generations to come. To share in the life of this collection, even briefly, is a privilege I do not take lightly. And to present it here in London—its spiritual home—is an honour beyond measure.

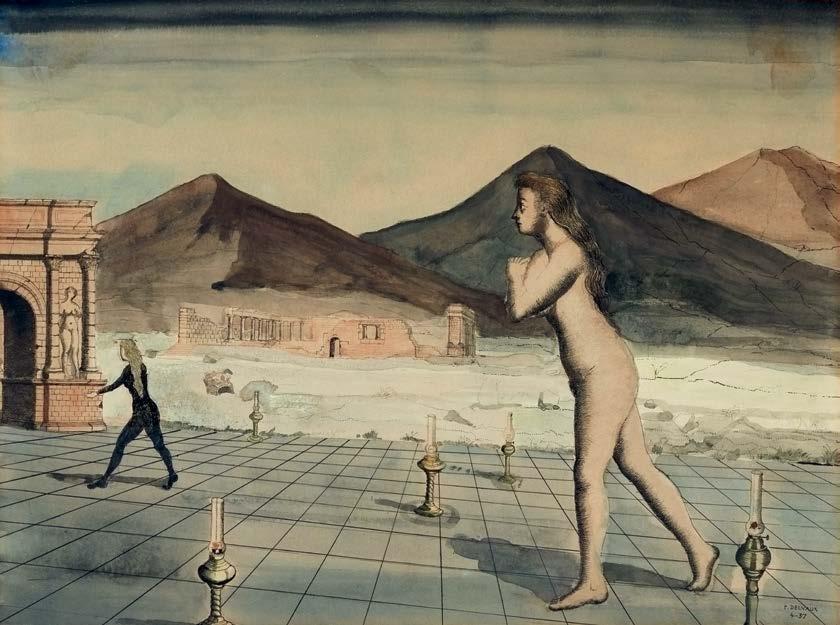

The extraordinary calibre of works presented here owes much to their esteemed provenance. It is an exceptional achievement that practically every work in the Karpidas Collection boasts a distinguished history of ownership. Many belonged to the collections of legendary figures such as Marina Picasso and Roland Penrose. Moreover, various provenances list celebrated cultural figures including the Surrealist artist Kurt Seligmann and wife Arlette (Ballon-Cœur by Ernst and Aurenche); English historian and poet Sir Herbert Read (Femmes et lampes by Paul Delvaux); and French poet and leading Surrealist Paul Éluard (Le Piano by Óscar Domínguez).

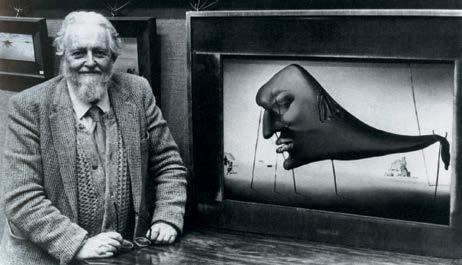

Many of these pieces also came from marketchanging single-owner sales. Guided by Alexander Iolas and Michel Strauss at Sotheby’s, Dinos and Pauline participated in some of the most prestigious auctions in history. Perhaps the watershed moment was the sale of William N. Copley’s collection on 5 and 6 November 1979 at Sotheby’s Parke Bernet in New York. William N. Copley (1919–1996)—also known as CPLY—was a New York-born artist, gallerist, writer, and patron who amassed a significant collection with a particular focus on Surrealist art. In 1948, he opened The Copley Galleries in Beverly Hills, exhibiting works by Magritte, Ernst, Tanguy, Matta, Cornell, and Man Ray. This venture was short-lived, closing only one year later. In 1951, Copley moved to Paris to focus on painting, and it was there that his passion for collecting truly flourished. He supplemented the pieces acquired during his gallery years with works by Jean Arp, Victor Brauner, Dorothea Tanning, Hans Bellmer, Alberto Giacometti, Joan Miró, Giorgio de Chirico, and Francis Picabia, among others. Over time, Copley’s collection became the largest assemblage of Surrealist art in private American hands.

On 5 and 6 November 1979, seeking to alleviate the burden of owning such a monumental collection, Copley sold most of the works acquired between 1947 and the mid-1970s in a record-breaking auction. At the time, it achieved the highest total on record for a single-owner sale in the United States. It was during this sale that Yves Tanguy’s Titre inconnu and Giorgio

de Chirico’s La Guerra and Portrait de Guillaume Apollinaire (the latter now reattributed to Max Ernst) were acquired for the present collection.

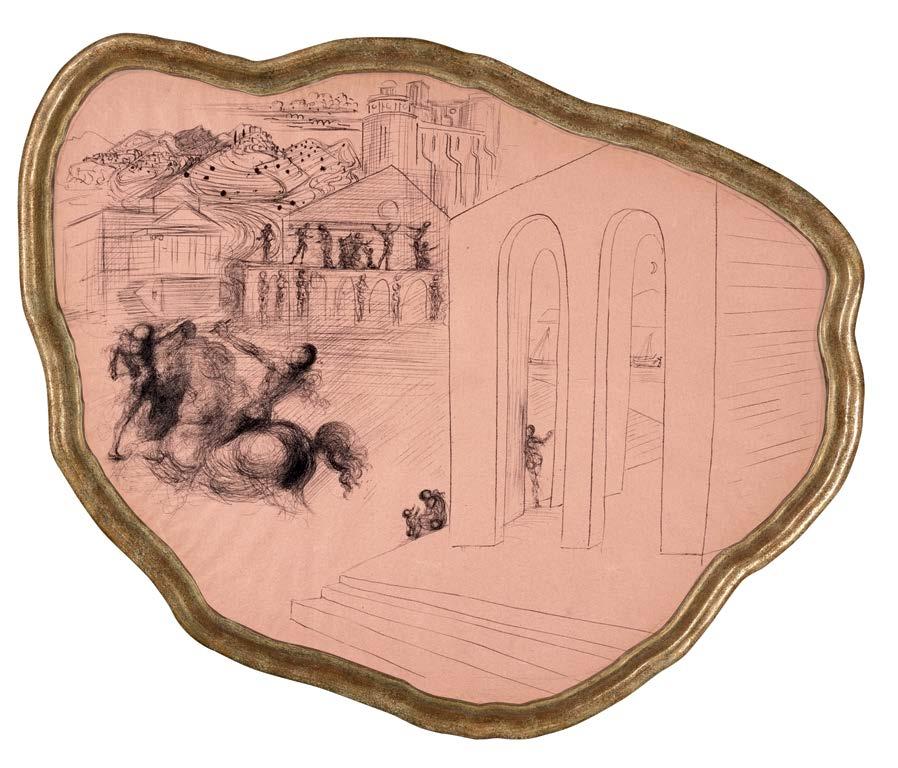

Similarly, Salvador Dalí’s Messager dans un paysage Palladien originally belonged to the ostentatious and enigmatic Surrealist patron Edward James (1907–1984), who likely acquired it directly from the artist almost immediately after it was completed around 1936.

Born into immense family wealth, James was educated at Eton and Oxford and seemed destined for a conventional upper-class English life. However, his eccentric character and talents led him elsewhere. As the James sale catalogue explains: “After leaving university he lived for the most part in Paris, where he soon became attached to the avant-garde circle around Éluard and Breton. He wrote poetry, much of which was published under the pseudonym Edward Selsey. He financed the Surrealist magazine Minotaure, which was published between 1933 and 1939, contributing poetry and essays himself […] Of the Surrealist

painters, his chief friends were Dalí, Magritte, and (later) Leonora Carrington. It was Dalí’s portrait of Marie-Laure, Vicomtesse de Noailles, which so inspired James that he went especially to Spain to find the artist. Thus began a notable period of patronage culminating in 1937–38, when Edward James took Dalí’s entire output in return for a generous allowance […] Circa 1940, Edward James went to the USA, and the Parisian Surrealist circle in which he had moved was equally dispersed. After the war, James continued to

spend most of his time in America” (“Introduction,” in Auction Catalogue, Christie’s, London, 28 Works from the Collection of Edward James, 5–6 November 1981, n.p.).

In 1964, James donated his considerable estate in West Sussex to a charitable trust and established the Edward James Foundation in 1971. Following his death, the Foundation sold many items from the West Dean estate in 1986. It was from this second James sale at Christie’s that Dalí’s Messager dans un paysage Palladien was acquired. Photographed in James’s

bedroom at Monkton House—a hunting lodge on the borders of his West Dean estate built by Sir Edwin Lutyens in 1902—this piece formed an integral part of James’s principal home. During the 1930s, James redesigned Monkton House with the aim of moving “away from that cottagey look” of Lutyens (Edward James in conversation, in: The Secret Life of Edward James, 1978, television documentary presented by George Melly). By painting the exterior purple, adding pillars of palm trees, plaster drapes beneath the windows, and padding the interior with fabric, James transformed Monkton into an eccentric homage to Surrealism.

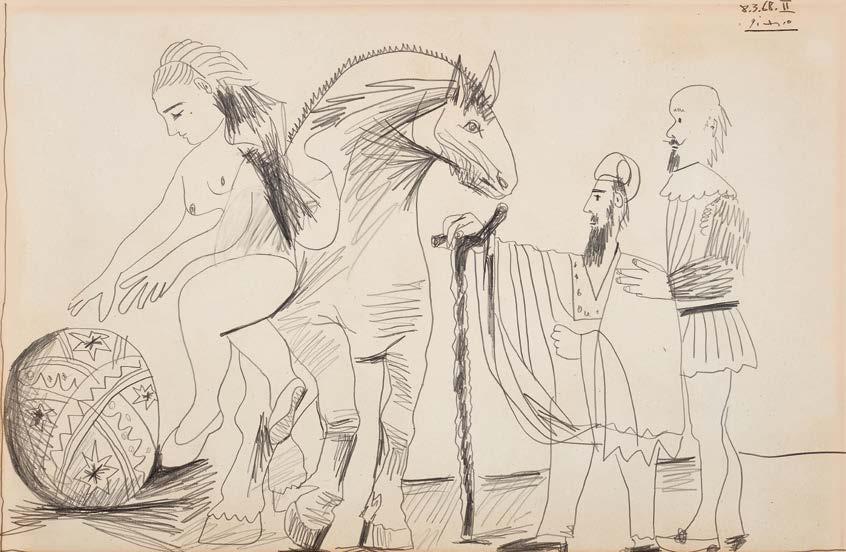

Also from Monkton are the suite of prints by Pablo Picasso, framed in wonderfully eccentric Louis XIV-styled white frames, as per Dalí’s own suggestion. Indeed, largely decorated by Dalí, Monkton remains one of the most ambitious and unconventional homes in design history, and its influence was evident in Pauline’s home at The Lancasters.

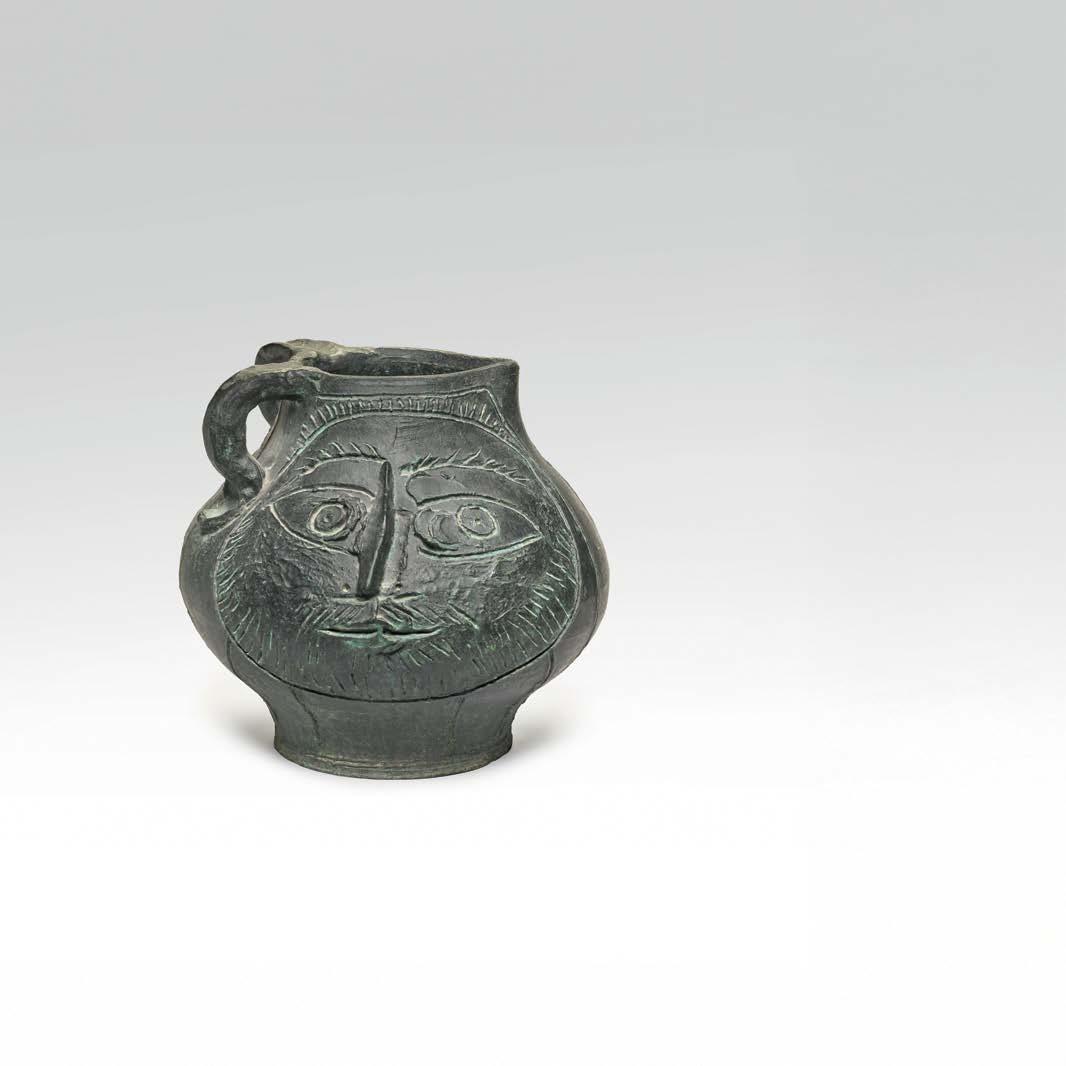

In addition to these important acquisitions, the collection comprises countless other works with distinguished histories of ownership. Victor Brauner’s Nous sommes trahis was purchased from the André Breton Estate sale at Calmels Cohen; Magritte’s Tête was acquired from the Magritte Studio sale at

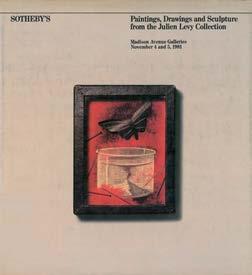

Sotheby’s; works by Man Ray were obtained from the Estate of Juliet Man Ray sale at Sotheby’s; while four works on paper by Max Ernst and Man Ray came from the single-owner sale of the eminent Surrealist dealer Julien Levy. Such is the calibre of this collection that almost every work’s provenance includes names such as Hélène Anavi, André-François Petit, Barnet Hodges, Marcel Jean, and André Meyer. Indeed, these pieces were acquired not only for their artistic merit but also for the remarkable lives they have led.

AND SOLD AT SOTHEBY’S

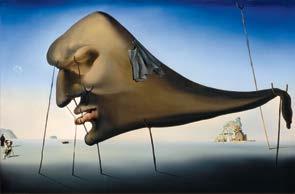

SALVADOR DALÍ LE SOMMEIL

1937

Sold privately at Sotheby’s ANDY WARHOL 200 ONE DOLLAR BILLS

1962

Sold at Sotheby’s New York, 11 November 2009

ANDY WARHOL SHADOW (RED)

1978

Sold at Sotheby’s New York, 10 May 2011

ANDY WARHOL SELF-PORTRAIT (FRIGHT WIG)

1986

Sold at Sotheby’s New York, 17 November 2016 WOLS VERT STRIÉ NOIR ROUGE (GREEN STRIPE BLACK RED)

1946-47

Sold at Sotheby’s London, 26 June 2019

IVAN KLIUN SPHERICAL SUPREMATISM 1920s

Sold at Sotheby’s London, 26 November 2019

RENÉ MAGRITTE L’OVATION

1963

Sold at Sotheby’s New York, 28 October 2020

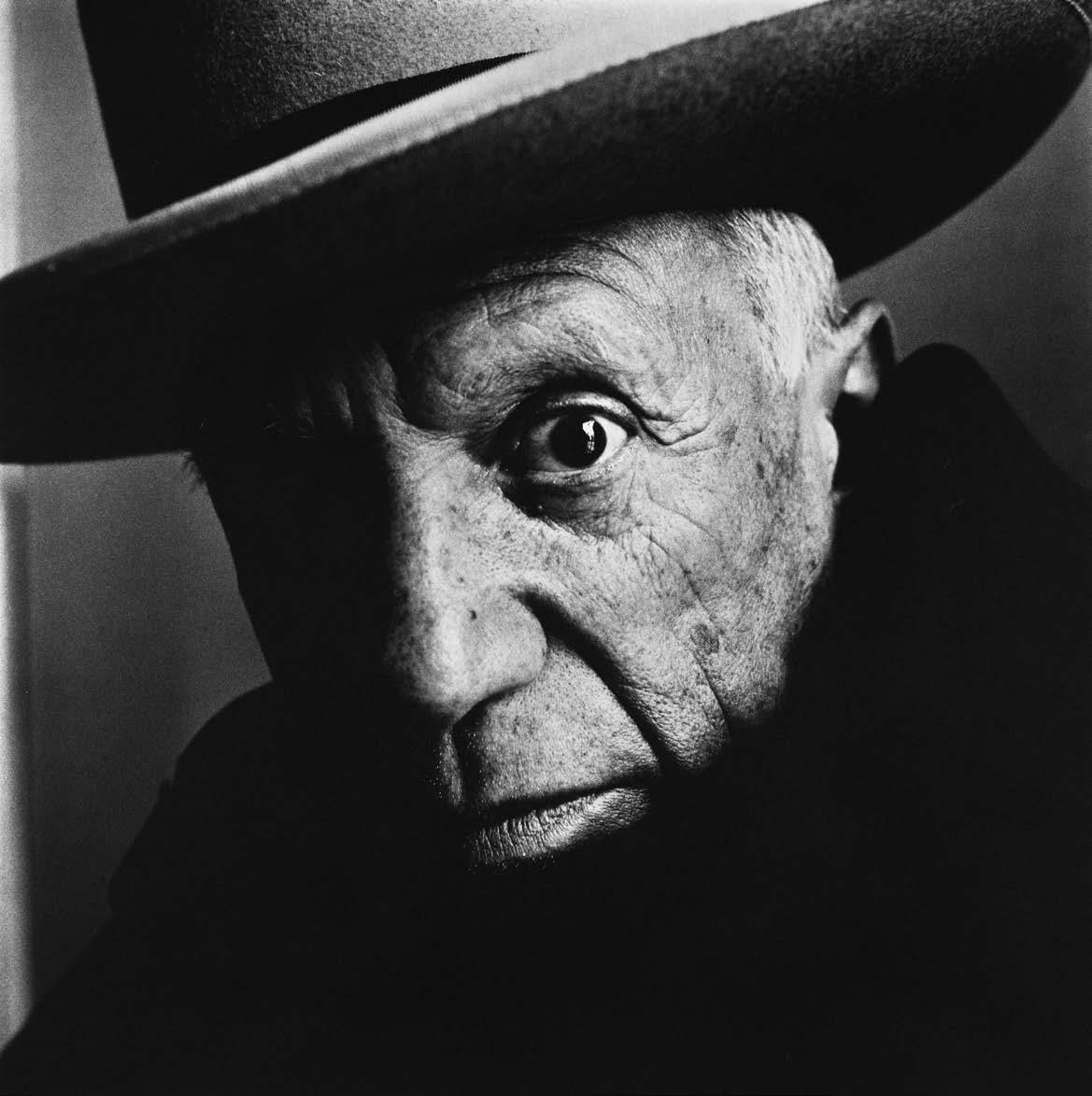

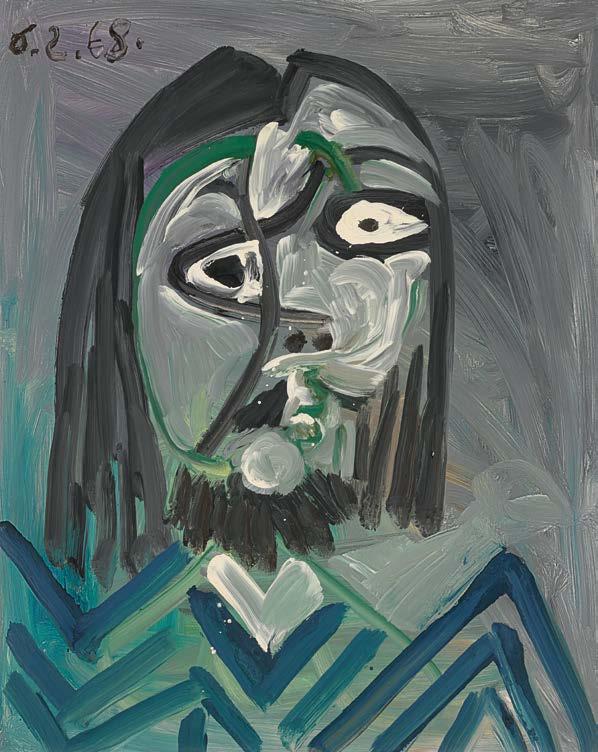

PABLO PICASSO HOMME À LA PIPE

1968

Sold at Sotheby’s London, 19 June 2019

PABLO PICASSO BUSTE D’HOMME

1969

Sold at Sotheby’s New York, 4 November 2009

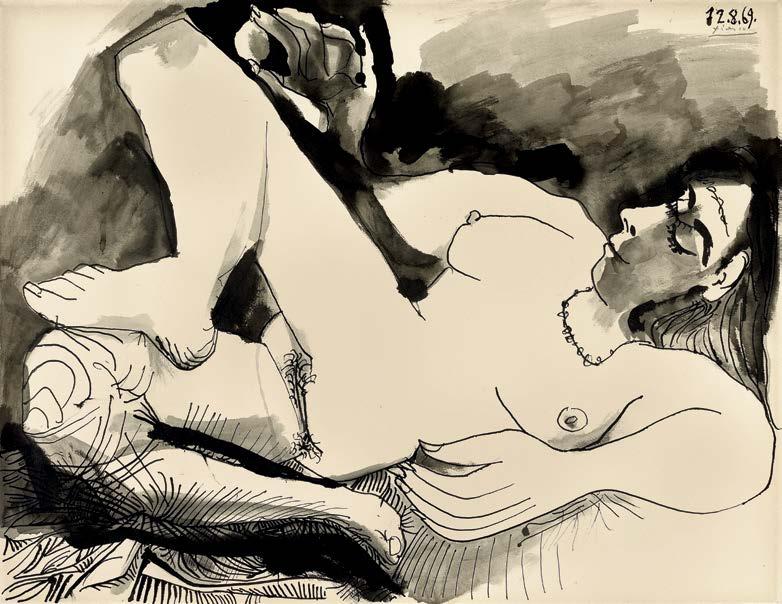

PABLO PICASSO NU COUCHÉ

1967

Sold at Sotheby’s London, 8 February 2011

PABLO PICASSO NATURE MORTE À LA TÊTE CLASSIQUE ET AU BOUQUET DE FLEURS 1933

Sold at Sotheby’s New York, 12 November 2019

HENRI MATISSE FENÊTRE OUVERTE: ETREAT 1920

Sold at Sotheby’s London, 24 June 1996

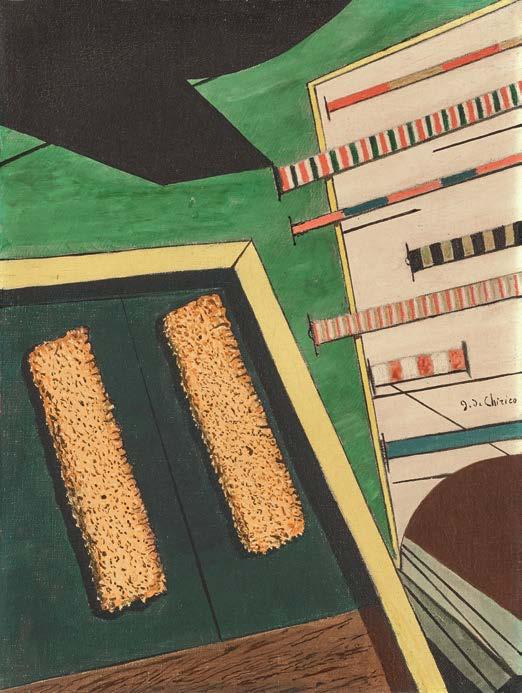

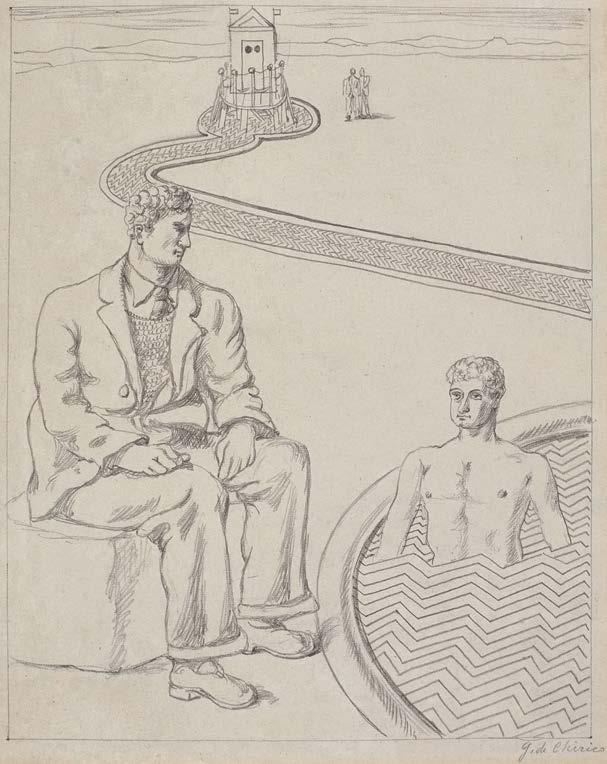

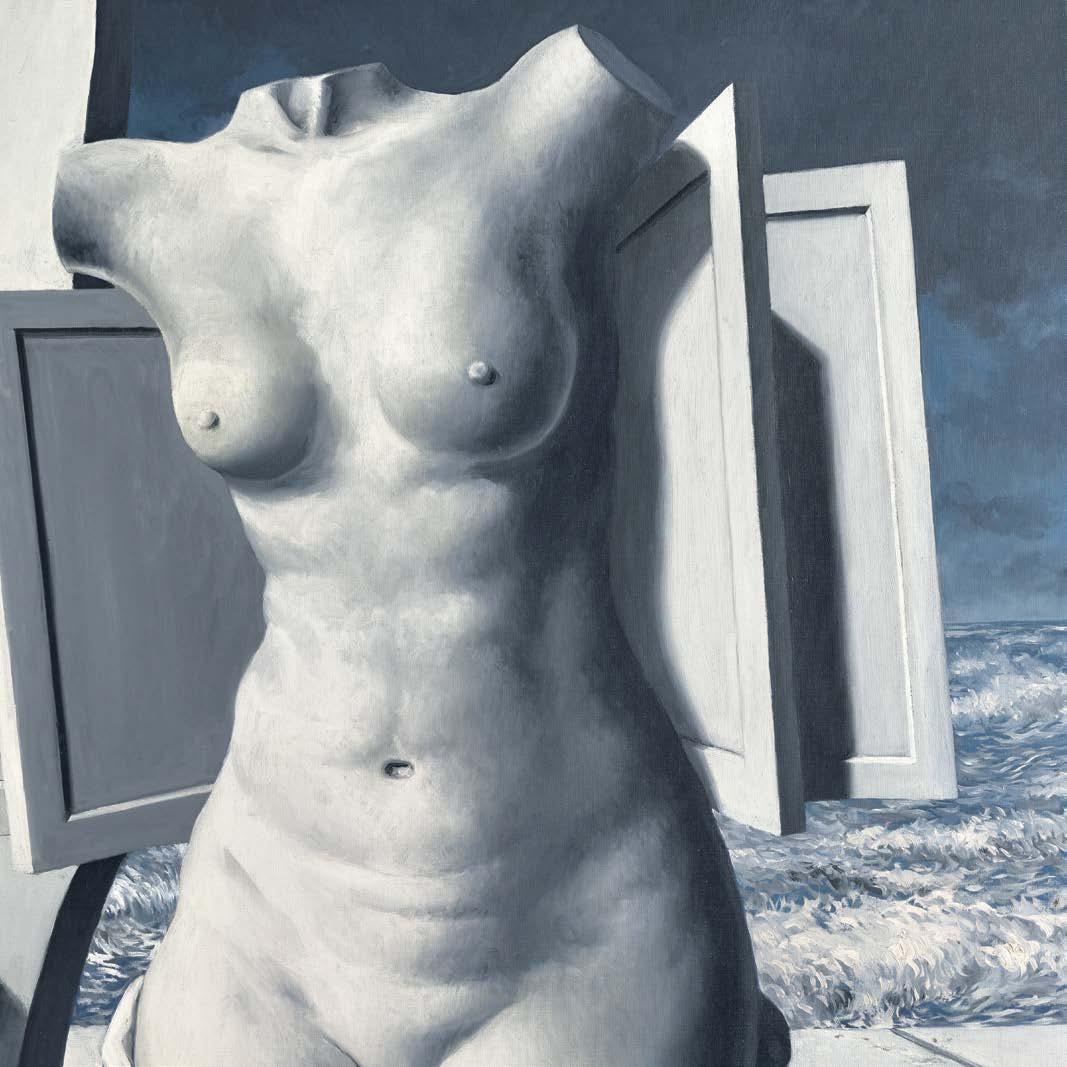

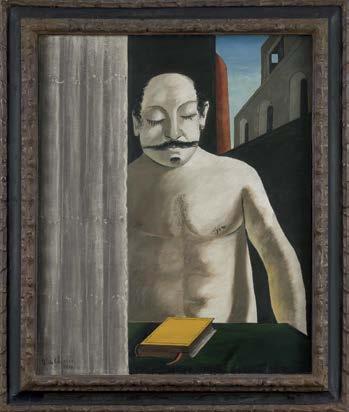

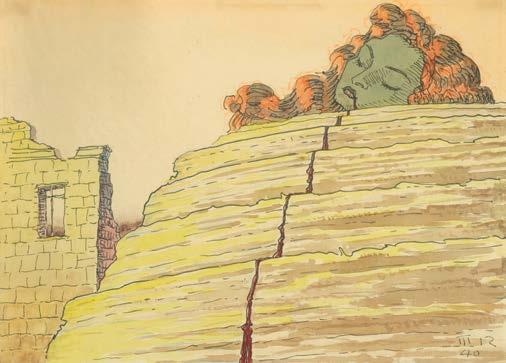

Although Giorgio de Chirico was never formally aligned with the Surrealist group, his early works exerted a profound influence on the development of Surrealist aesthetics. Born in Greece to Italian parents and trained in Athens, Florence, and later Munich, de Chirico fused classical references with Symbolist legacy and German metaphysical philosophy to articulate a new pictorial language that explored the uncanny and the unknowable. His paintings from the 1910s—marked by melancholic, sun-drenched piazzas, incongruous shadows, and enigmatic objects, as seen in the proto-Surrealism of La Guerra—set the stage for what André Breton would later recognise as foundational to Surrealism. These early ‘metaphysical’ compositions generate a sense of temporal suspension and latent narrative that the Surrealists would eagerly embrace in their pursuit of the unconscious.

De Chirico’s wartime experience and subsequent meeting with Carlo Carrà in Ferrara solidified what would become the Scuola Metafisica. Though he later distanced himself from modernism and criticised his early work, the visual strategies he pioneered— dislocation, dreamlike spatiality, and ontological ambiguity—remained central to Surrealism’s exploration of irrationality. His early paintings offered a model for employing traditional techniques to conjure deeply untraditional, destabilising worlds, and artists such as Max Ernst, René Magritte, and Yves Tanguy owed much to his metaphysical vision.

NUDO

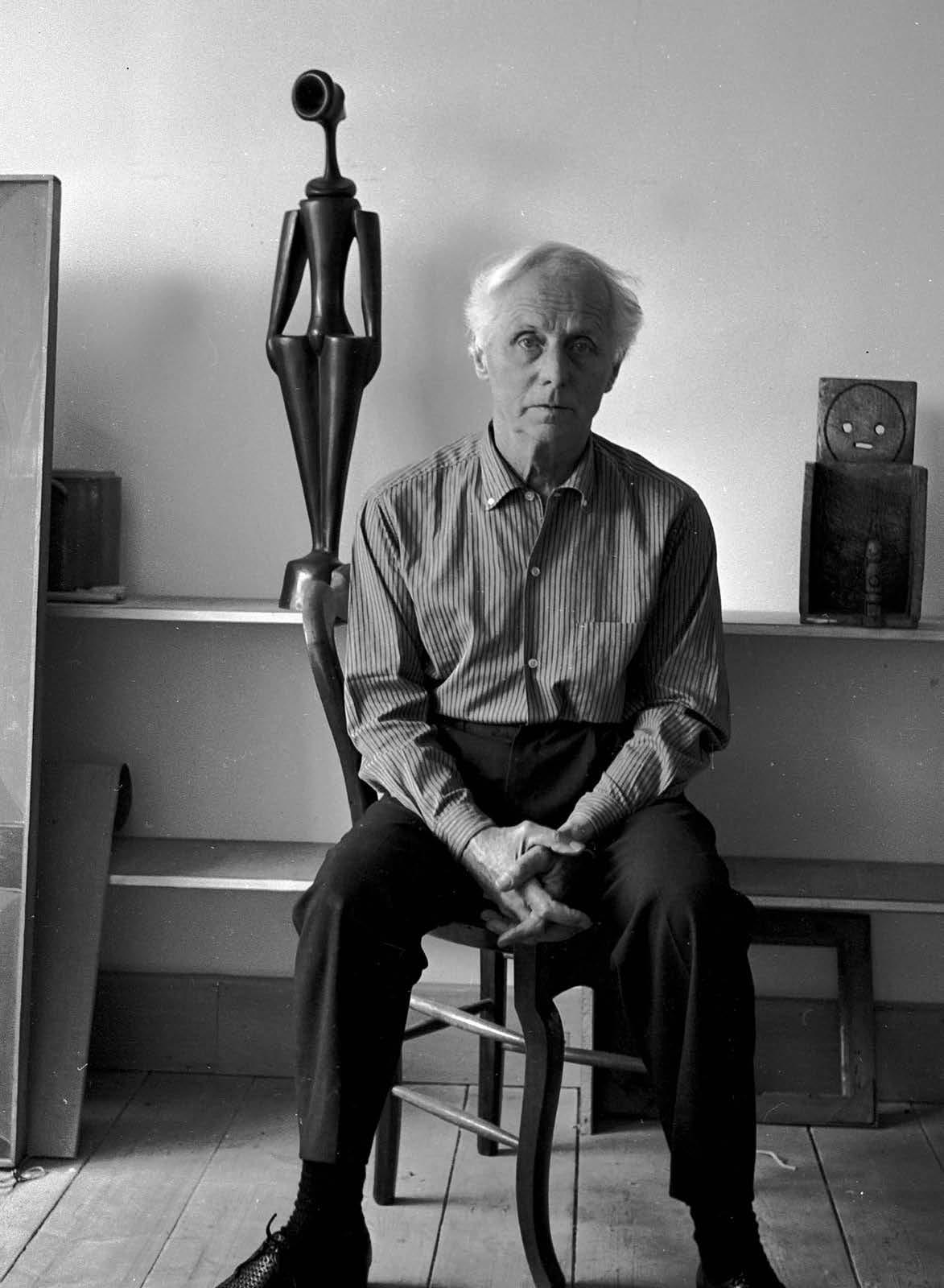

RITRATTO DI ALEXANDER IOLAS

(PORTRAIT OF ALEXANDER IOLAS)

BAGNI MISTERIOSI (MYSTERIOUS BATHS)

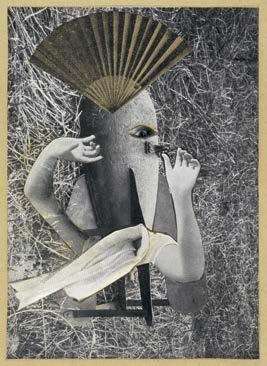

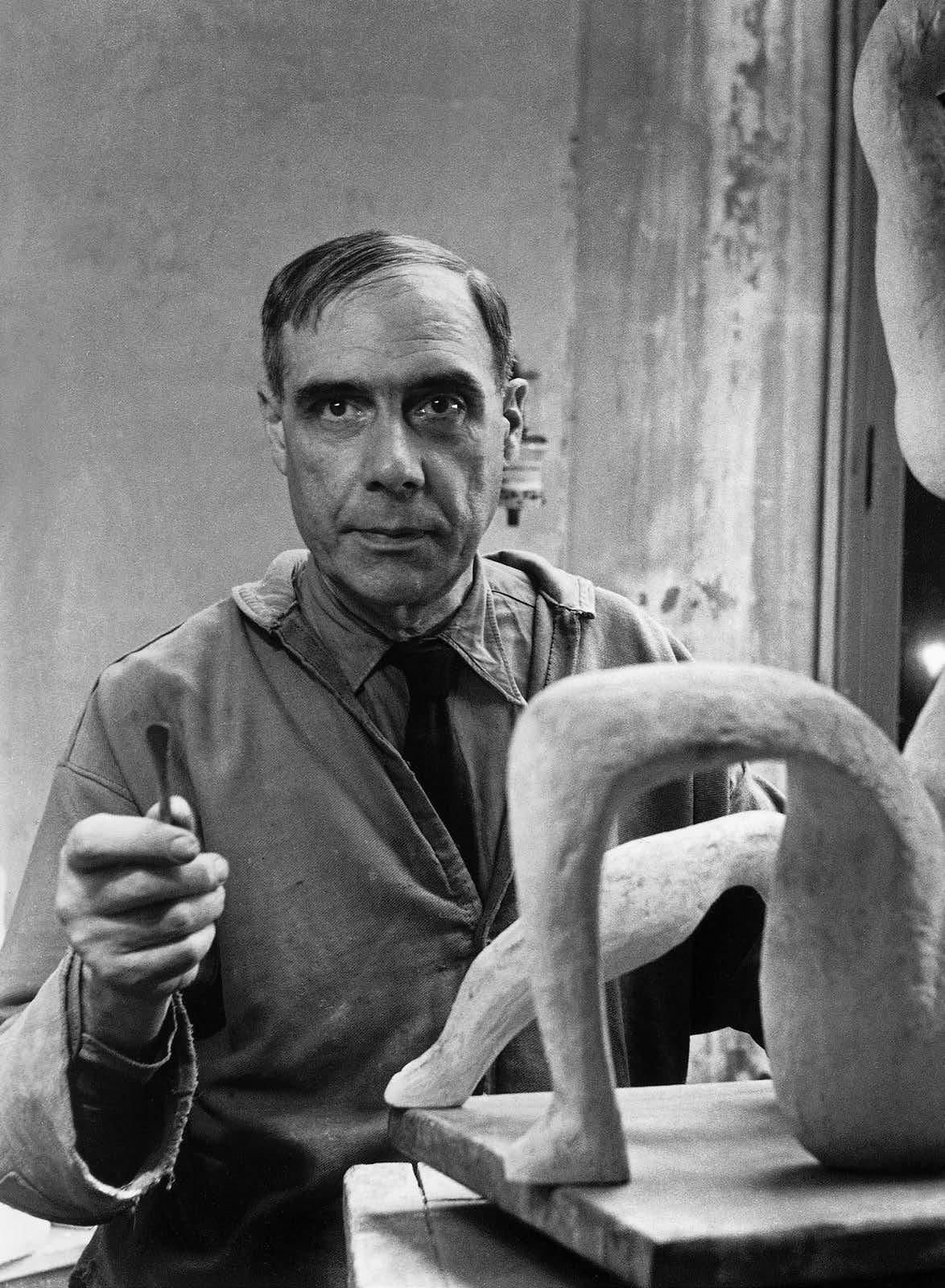

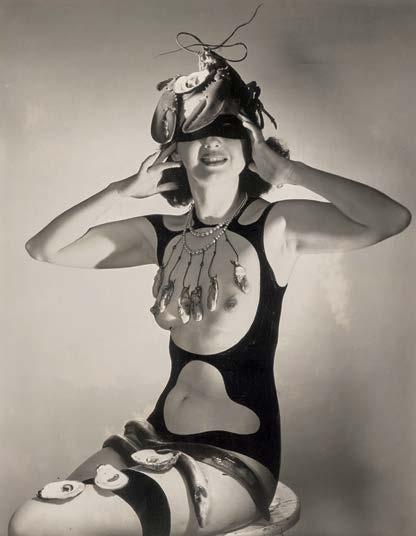

The international scope of Surrealism can be clearly traced through the trajectory of Max Ernst’s career. His earliest contributions emerged as part of the Cologne Dadaists, creating works characterised by collage, which he described as “a meeting of two realities on a plane foreign to them both.” This reveals a simultaneity of Dadaist thought across different European centres—while Marcel Duchamp was similarly doctoring images in Paris, exemplified by his infamous L.H.O.O.Q., Hannah Höch was developing photomontage techniques in Berlin. Whereas Höch used images cut from magazines to satirise contemporary cultural and gender politics, Ernst preferred to explore mechanical and biological themes. Similarly, Claude Cahun’s photographic superimpositions, contemporaneous with Höch’s, broached the gender spectrum, reflecting Surrealism’s belief in the fluidity of sexual identity.

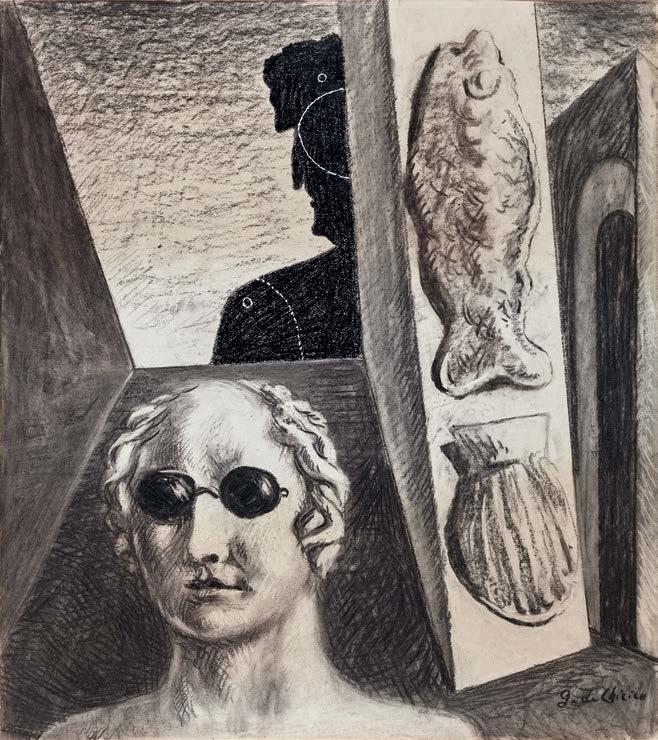

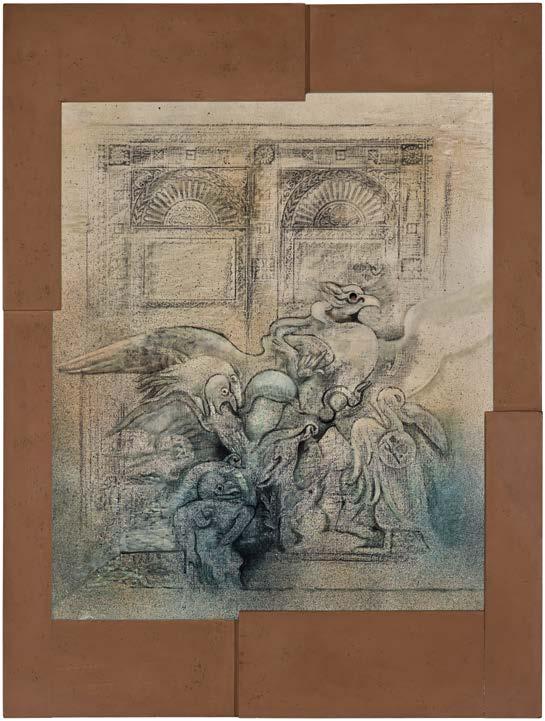

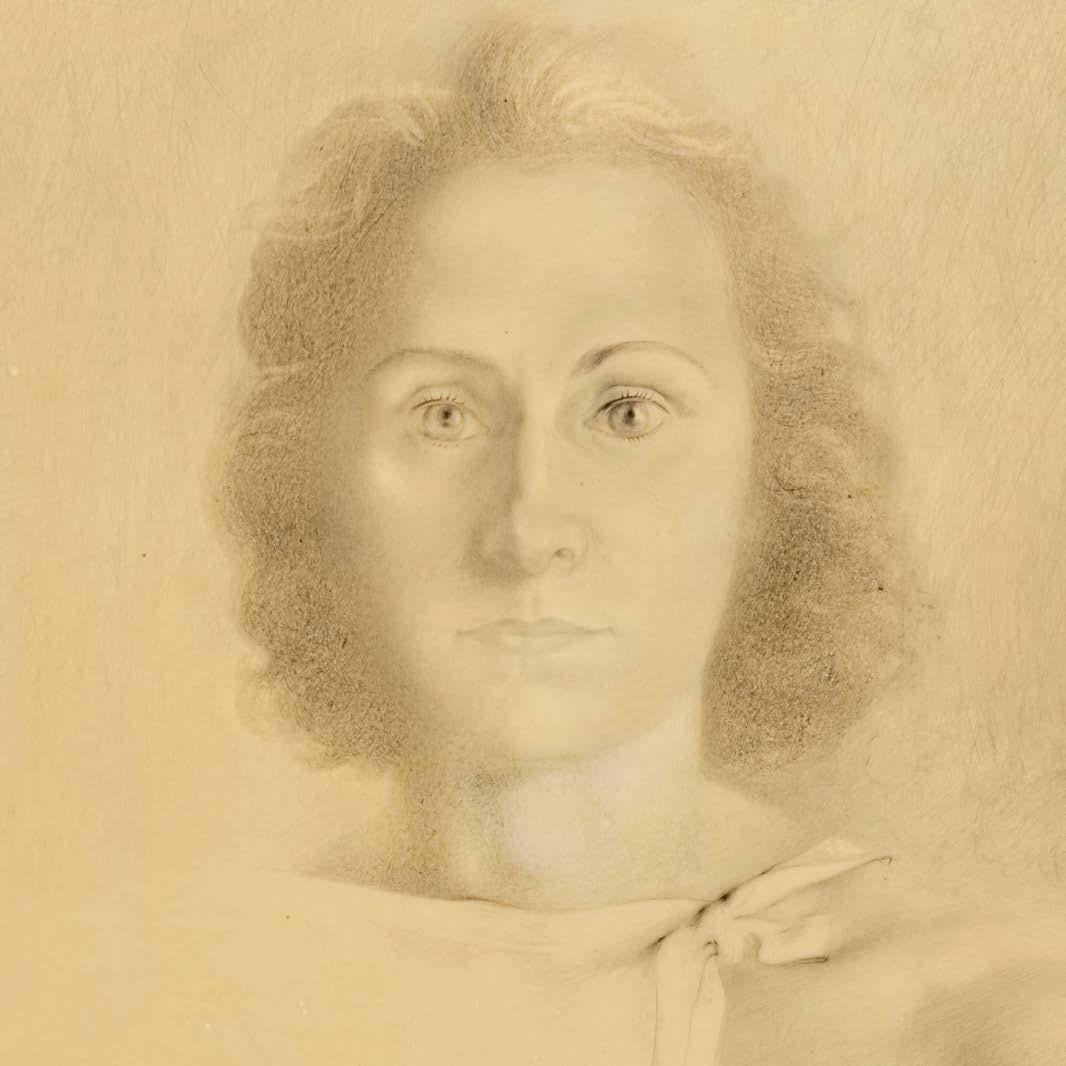

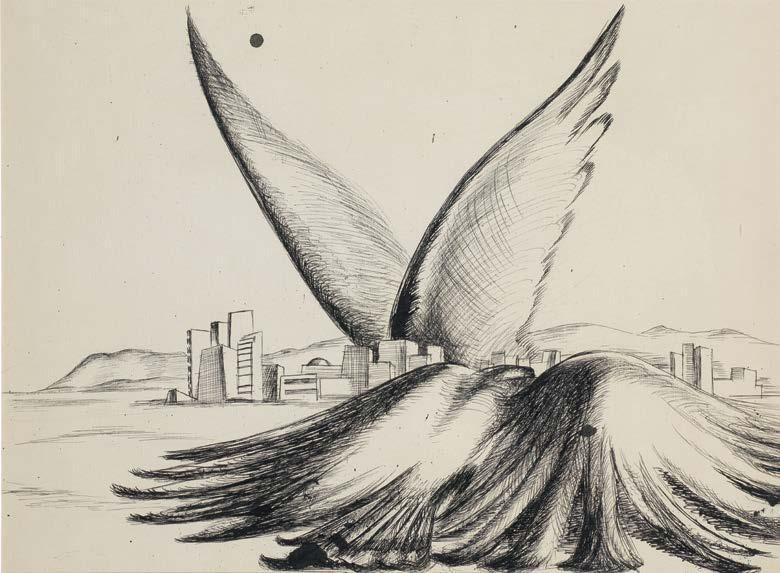

Ernst subsequently spent the 1920s and 1930s in Paris as a key member of the Surrealist movement, working alongside Breton, Tanguy, Carrington, and Masson, among others, while developing his own distinctive Surrealist idiom. A notable work from this period is Ernst’s Portrait de Guillaume Apollinaire (1934), a striking charcoal drawing long misattributed to Giorgio de Chirico. Bearing a forged signature backdating it to 1913, the drawing exemplifies Surrealism’s complex play with authorship, originality, and artistic appropriation.

The outbreak of war and his brief internment prompted Ernst, along with several contemporaries, to flee France for the United States. Carrington, Ernst’s lover in Paris, also fled abroad, settling in Mexico among a new nexus of Surrealist artists. In New York, the Surrealist exiles flourished. Although Matta had been introduced to Surrealism through Breton in 1920s Paris, he exhibited alongside Ernst, Masson, Tanguy, and Breton in the now infamous Artists in Exile exhibition in New York in 1942. It was also here that Ernst met—and later married—the American artist Dorothea Tanning, who became another leading figure in Surrealist art. Their presence in the United States profoundly influenced a slightly later generation of American artists such as Joseph Cornell, who was especially inspired by Ernst’s poetic conception of collage.

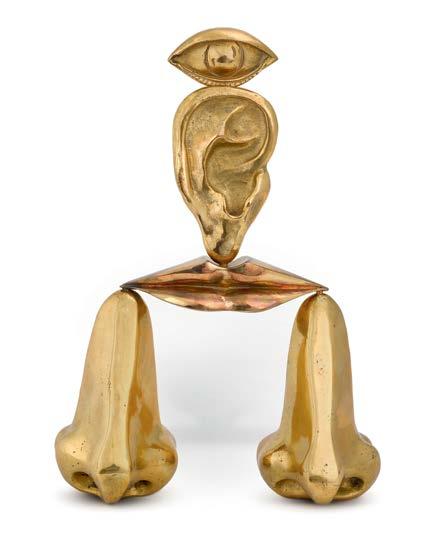

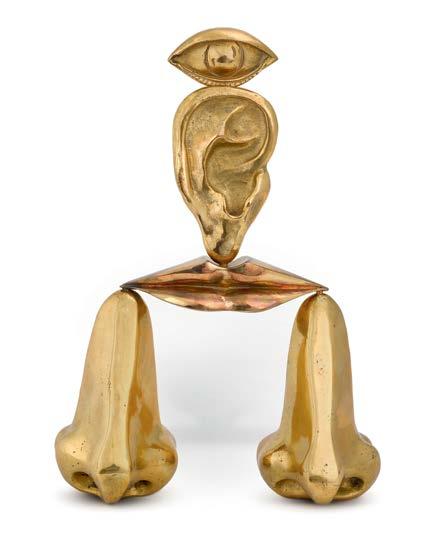

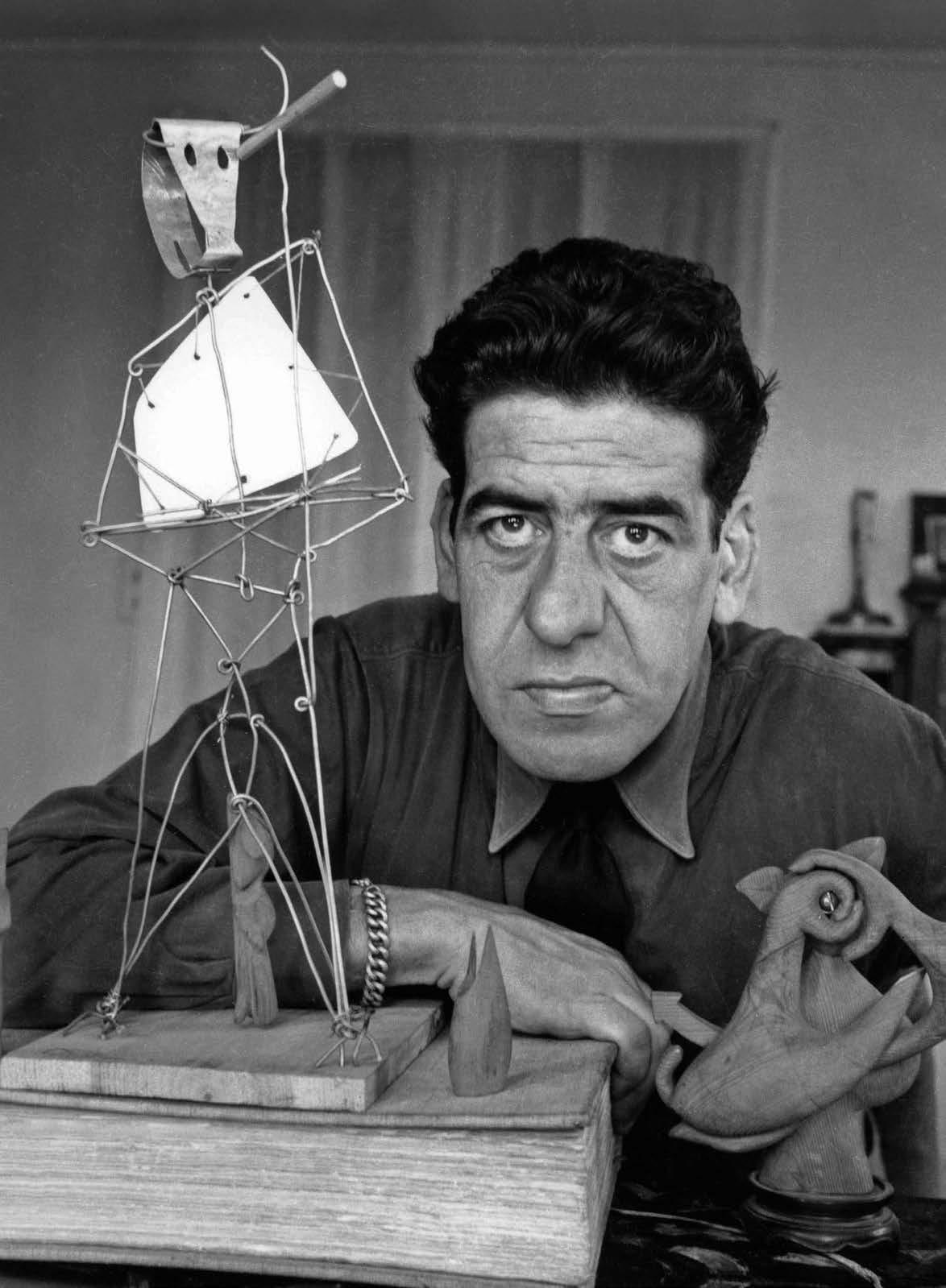

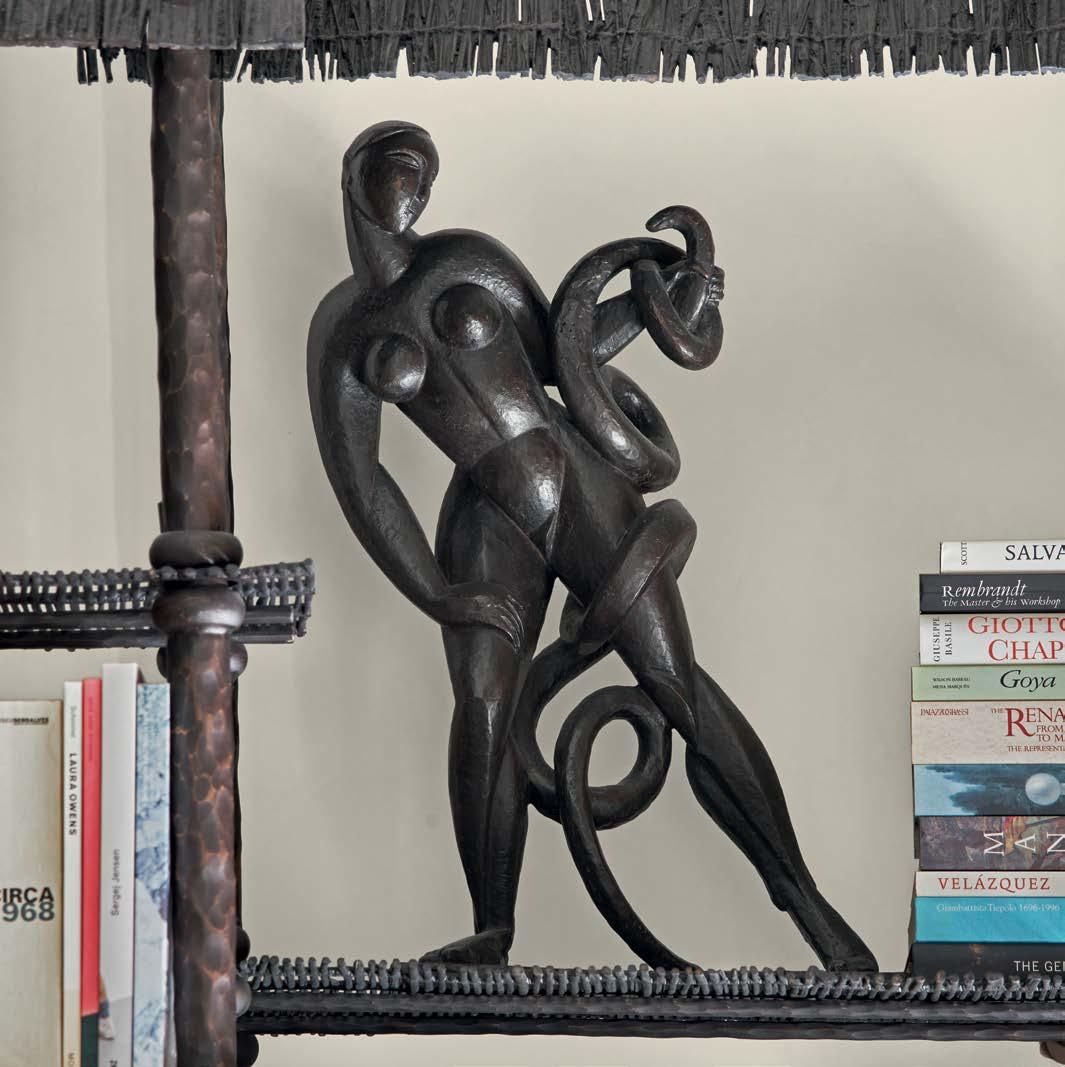

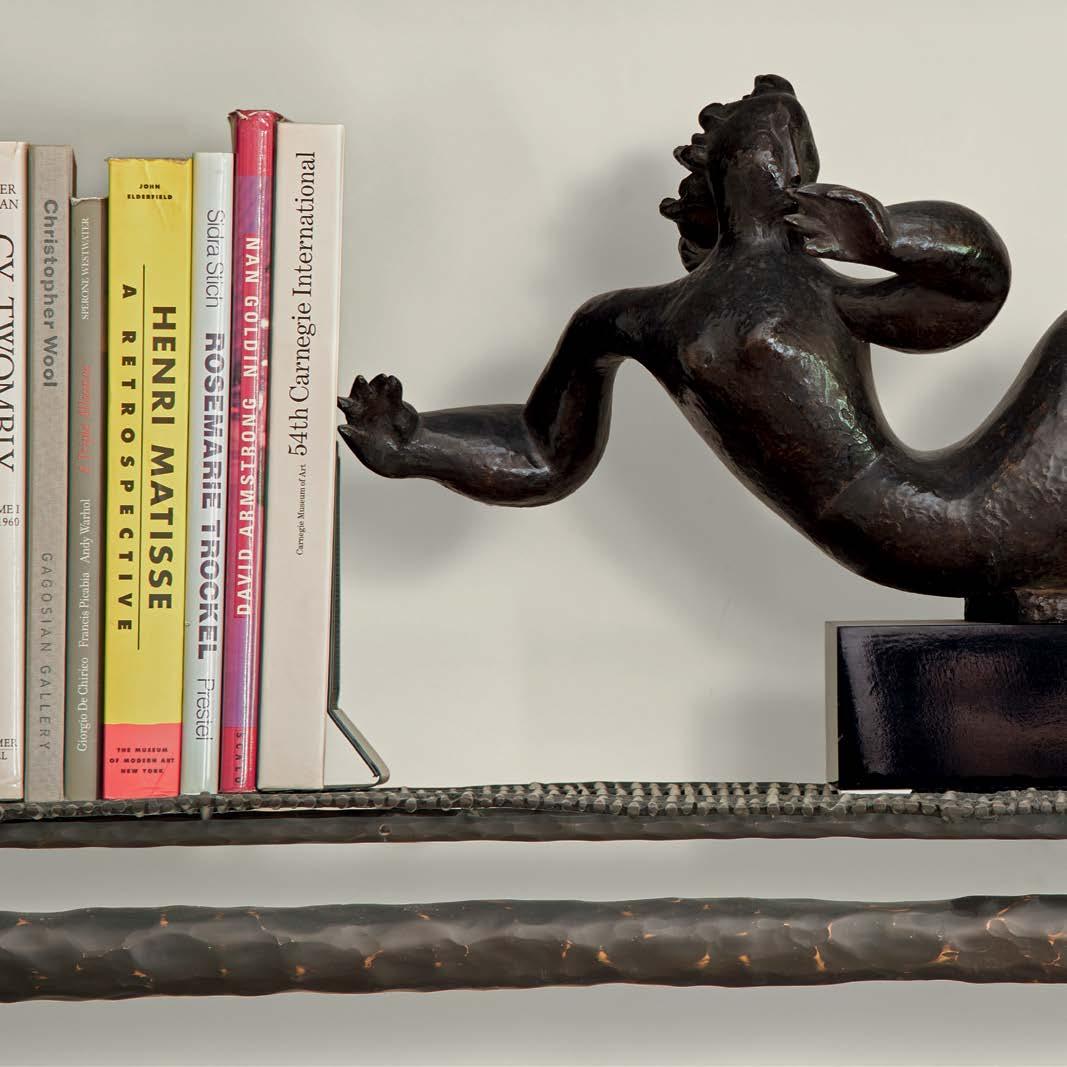

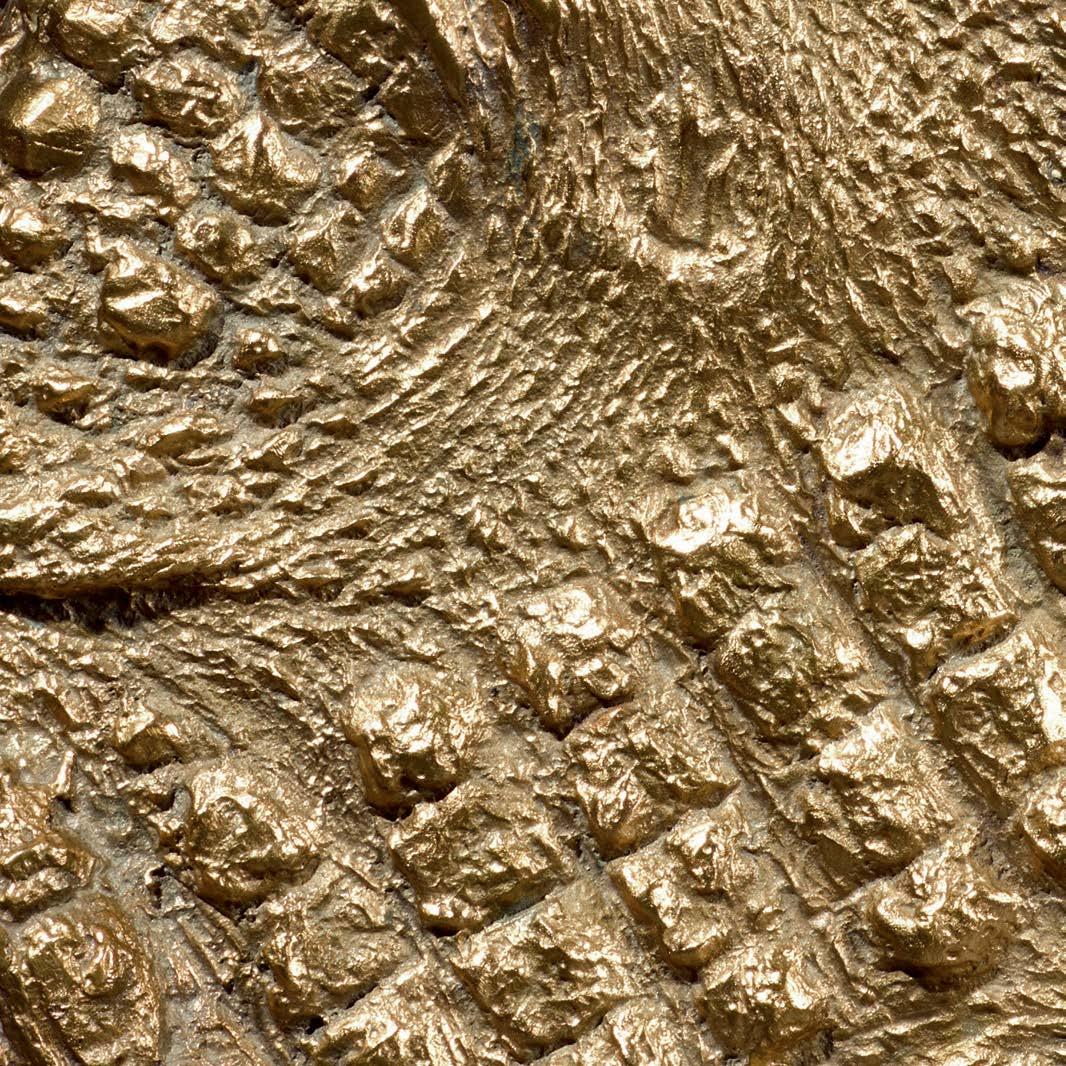

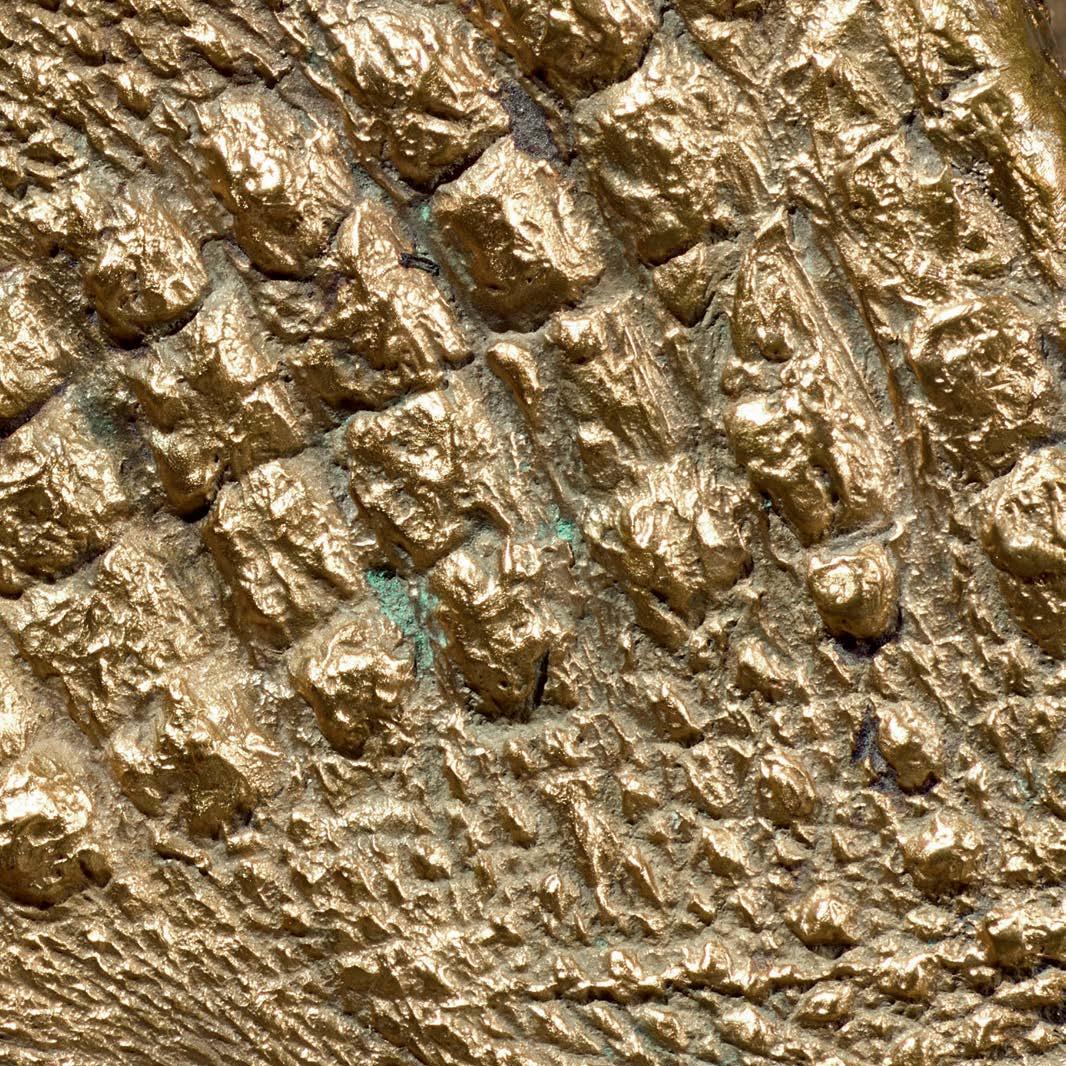

The post-war years brought increased international recognition for Ernst, culminating in the award of the Grand Prix at the Venice Biennale in 1954. During this period, many of his radical sculptural experiments from the 1930s and 1940s were cast in bronze for the first time. Notable examples include Jeune homme au cœur battant and La Plus belle, which oscillate between abstraction and figuration. Their simplified, humorously humanised geometric forms encapsulate the concept of play, a principle foundational to the earliest tenets of Surrealism.

MAX ERNST

PORTRAIT DE GUILLAUME APOLLINAIRE

inscribed G. de Chirico (lower right) charcoal, pastel and gouache on paper 62 by 55.1 cm. 24⅜ by 21¾ in. Executed in 1934.

Formerly in the collections of Paul

JEUNE HOMME AU CŒUR BATTANT OR SATEUR DE MUR OR OISEAU VOLE

with the foundry mark MODERN ART FDRY. N.Y. bronze height (including base): 65.5 cm. 25¾ in.

Conceived in 1944; this example cast by the Modern Art Foundry, Long Island between 1953 and 1956 in an edition of 8 unnumbered casts. 3 additional posthumous casts were produced by the Modern Art Foundry, Long Island in 1994.

inscribed max ernsT and numbered 00/5 bronze height: 180 cm. 70⅞ in.

Conceived in 1967; this example cast by the Fonderia Fratelli Bonvicini, Verona between 1969 and 1974 in an edition of 9 casts. 7 additional posthumous casts were produced by the Modern Art Foundry, Long Island in the late 1990s.

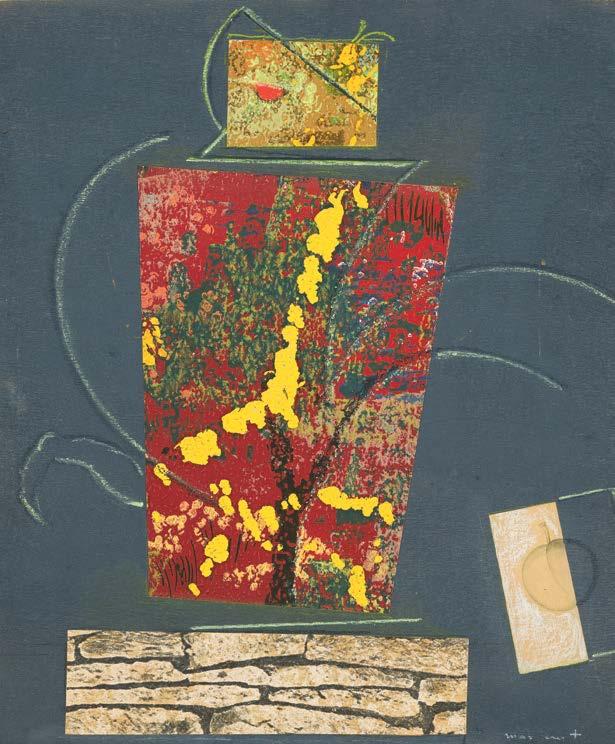

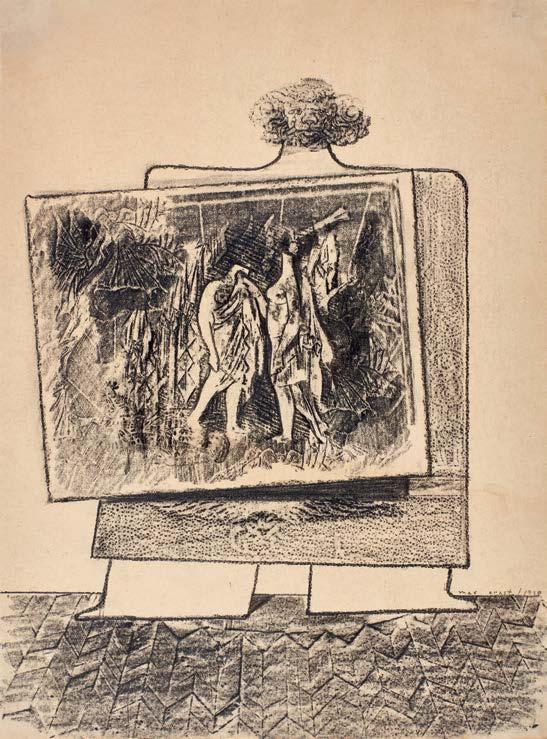

MAX ERNST LOPLOP PRÉSENTE

signed max ernst (lower right); dedicated á mon très cher ami Joë Bousquet (lower left) collage, pencil and frottage on paper

48.5 by 64.5 cm. 19⅛ by 25⅜ in.

Executed in 1931.

Formerly in the collection of Joë Bousquet.

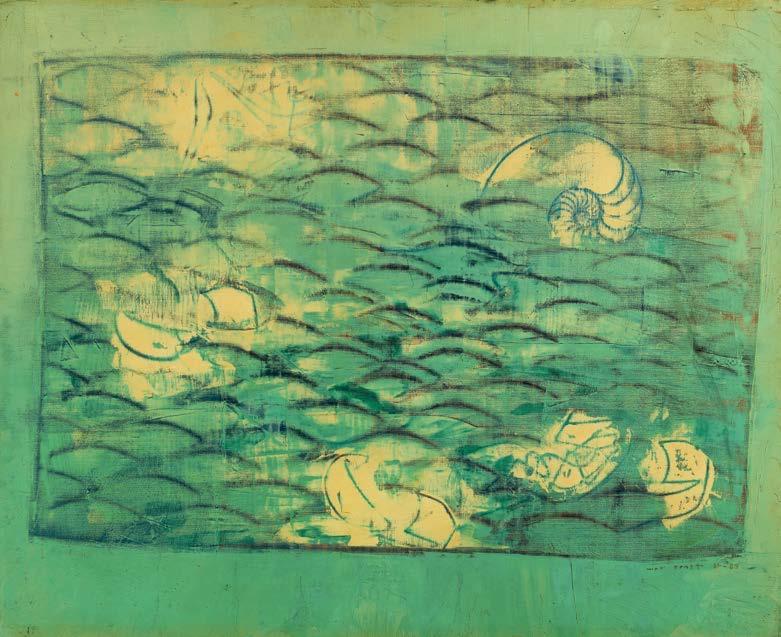

COQUILLAGE MER VERTE

signed max ernst and dated 64-65 (lower right); dated 1965 and inscribed une armée de harengs (on the stretcher) oil on canvas

62.4 by 76 cm. 23⅝ by 29⅞ in.

Executed in 1964-65.

ERNST LOPLOP PRÉSENTE

signed max ernst and dated / 1930 (lower right) pencil and frottage on paper 31.1 by 22.8 cm. 12½ by 8⅞ in. Executed in 1930.

Formerly in the collection of Julien Levy.

MAX ERNST LOPLOP PRÉSENTE

signed max ernst and numbered 5/6 (lower right) oil and collage on plaster 99.2 by 120.6 cm. 39⅛ by 47½ in. Executed in 1929-68. This work is number 5 from an edition of 7.

JEUNE FEMME EN FORME DE FLEUR OR FEMME FLEUR OR FIGURE PRINTANIÈRE

bronze height: 36.2 cm. 14¼ in.

Conceived in 1944 and cast between 1954 and 1961 in an edition of 9 unnumbered casts; 1 by Roman Bronze Works, Inc., New York in 1954; 4 by the Modern Art Foundry, Long Island in 1955; and 4 by the Modern Art Foundry, Long Island in 1961. 3 posthumous signed and numbered casts were produced by the Modern Art Foundry, Long Island in 1999.

inscribed Max Ernst, numbered 2/9 and with the foundry mark Susse Fond Paris bronze height: 78.5 cm. 30⅞ in.

Conceived in 1950; this example cast by Susse Fondeur, Paris between 1958 and 1973. This work is number 2 from an edition of 9 plus 1 zero cast and 4 lettered HC casts.

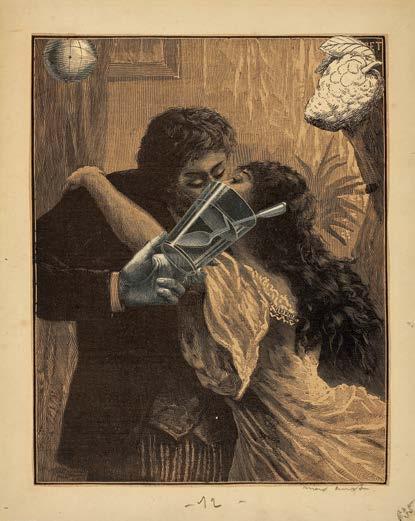

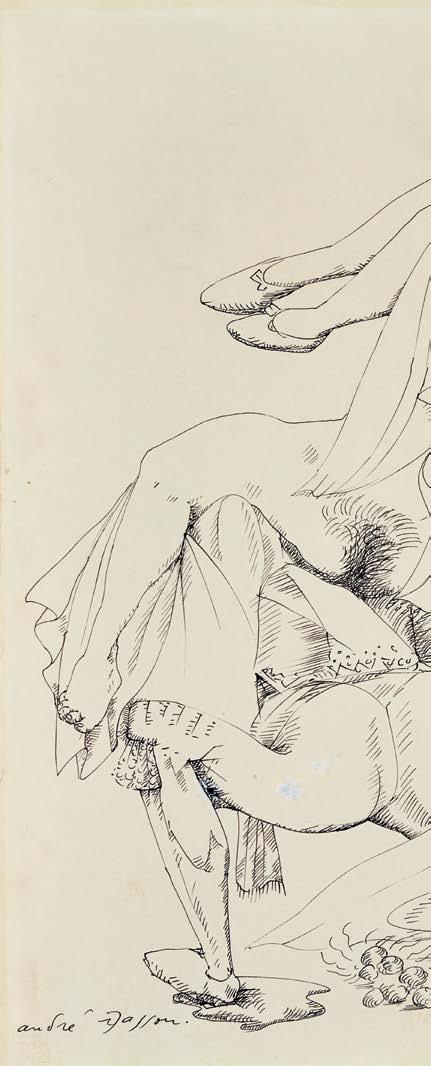

MAX ERNST

LE PÈRE: “VOTRE BAISER ME SEMBLE ADULTE, MON ENFANT, VENU DE DIEU, IL IRA LOIN. ALLEZ, MA FILLE, ALLEZ EN AVANT ET...”

signed max ernst (on the artist’s mount)

collage mounted on paper sheet: 24.3 by 19.3 cm. 9½ by 7⅝ in. artist’s mount: 30 by 23.3 cm. 11⅞ by 9⅛ in.

Executed in 1929-30.

Formerly in the collection of Julien Levy.

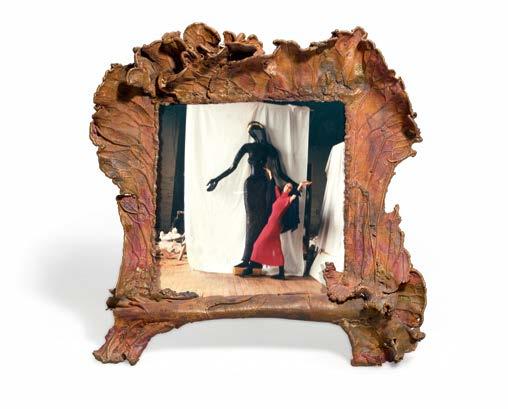

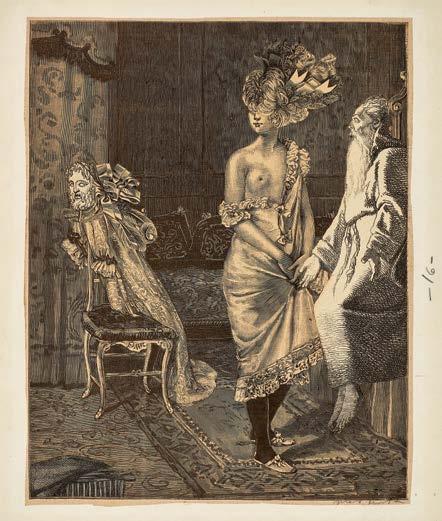

MAX ERNST

“...JUSQU’À ÉPUISEMENT COMPLET DES BEAUX DANSEURS!”

signed max ernst (lower right) collage mounted on paper sheet: 24.7 by 19.4 cm. 9¾ by 7⅜ in. artist’s mount: 29.8 by 24.4 cm. 11¾ by 9⅝ in. Executed in 1929-30.

Formerly in the collection of Julien Levy.

COMPOSITION AUX OISEAUX

signed max ernst (lower right) oil and frottage on canvas in the artist’s frame 55 by 46 cm. 21⅝ by 18⅛ in. artist’s frame: 73.2 by 55.2 cm. 28¾ by 21⅝ in. Executed circa 1931.

Formerly in the collection of Jacques Kugel.

Formerly in the collection of Kurt

BY EMMA BAKER

Pauline Karpidas belongs to the last of the twentieth century’s indomitable fellowship of Grande Dames; women whose deep commitment and influential patronage fundamentally shaped the way art is collected, exhibited and appreciated today. From Gertrude Stein and Peggy Guggenheim, to São Schlumberger and Dominique de Menil, Pauline’s name bookends a chronicle of art world bohemia in which high-society tradition blended with avantgarde radicality. A heady mix of artists, gallerists, intellectuals, patrons and socialites brought forth a mythology characterised by theatrical personalities, glamourous soirées and notorious encounters.

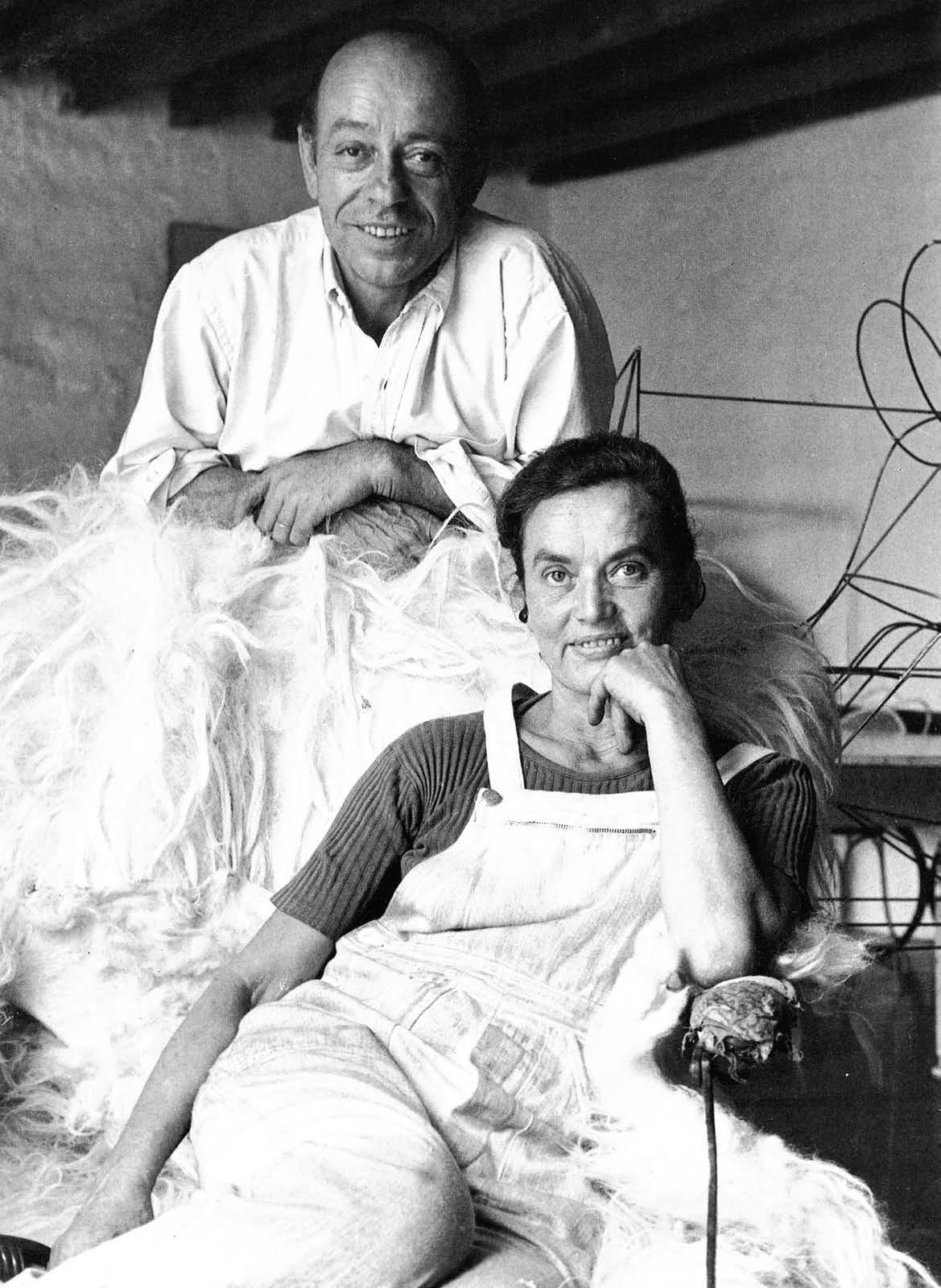

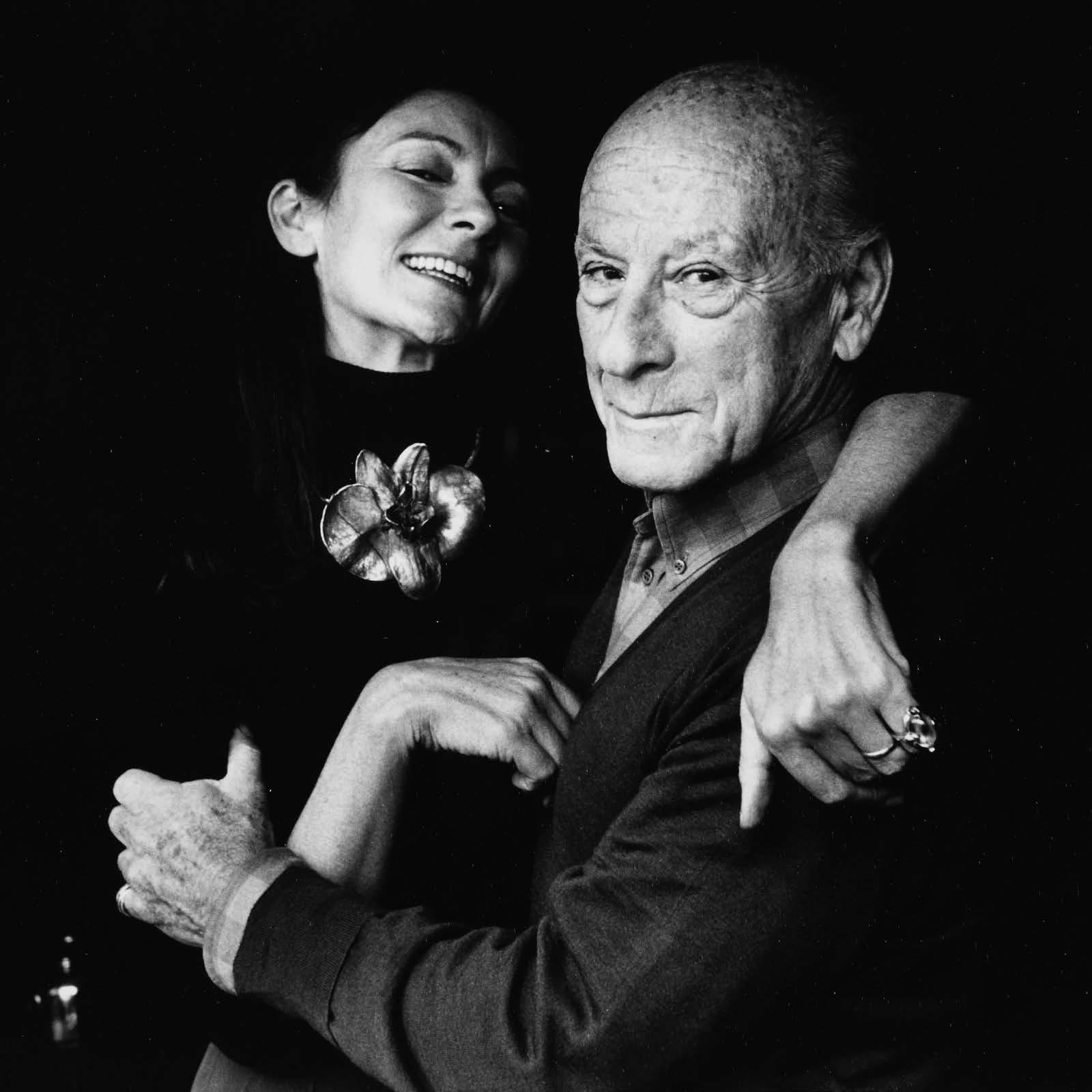

Gertude Stein’s cerebral salons of the 1920s, Peggy Guggenheim’s unconventional lifestyle and patronage of Abstract Expressionism in the 1940s, Sau Schlumberger’s extravagant parties of the 1960s, and Dominique de Menil’s intellectual dedication and steadfast philanthropy, all constitute moments in a vital story that Pauline Karpidas would become an indelible part of. In many ways, Pauline’s important contribution forms the final act in this bohemian tale of twentieth century art history. A key figure within this story, and the single biggest influence for Pauline, was the flamboyant and keenly astute dealer Alexander Iolas. It was their meeting in 1974 at Iolas’s Athenian mansion that ignited a life dedicated to art, beauty and philosophy; the beginning of what Pauline would describe to me as her “beautiful journey”. From modest means came grand accomplishments: Pauline’s story is an extraordinary tale of transformation. With Iolas playing fairy godmother, it is the art world’s answer to the classic Cinderella fairytale.

Born Pauline Parry in 1942 to a working class family in Manchester, Pauline’s upbringing was one of humble beginnings and hard graft. When her father became unable to work owing to epilepsy, her mother took on the role of principal breadwinner as an early-morning cleaner. By the age of 12 Pauline had started working odd jobs at the local market, and by 15 she had enrolled in secretarial school for a local timber merchants. With an industrious attitude and a vivacious, theatrical personality—she was constantly singing at work and even played Eliza Doolittle in a local youth production—Pauline became an office PA at 18 and began modelling at 19: an early career that jump-started an abiding love affair with travel and fashion. In her 20s, driven by an ever-pervasive entrepreneurial spirit, she began running a clothes boutique in Athens. The shop was named My Fair Lady (after Pauline’s longtime affinity with Audrey Hepburn’s Eliza) and it was here that Pauline would meet her future husband, Constantinos Karpidas.

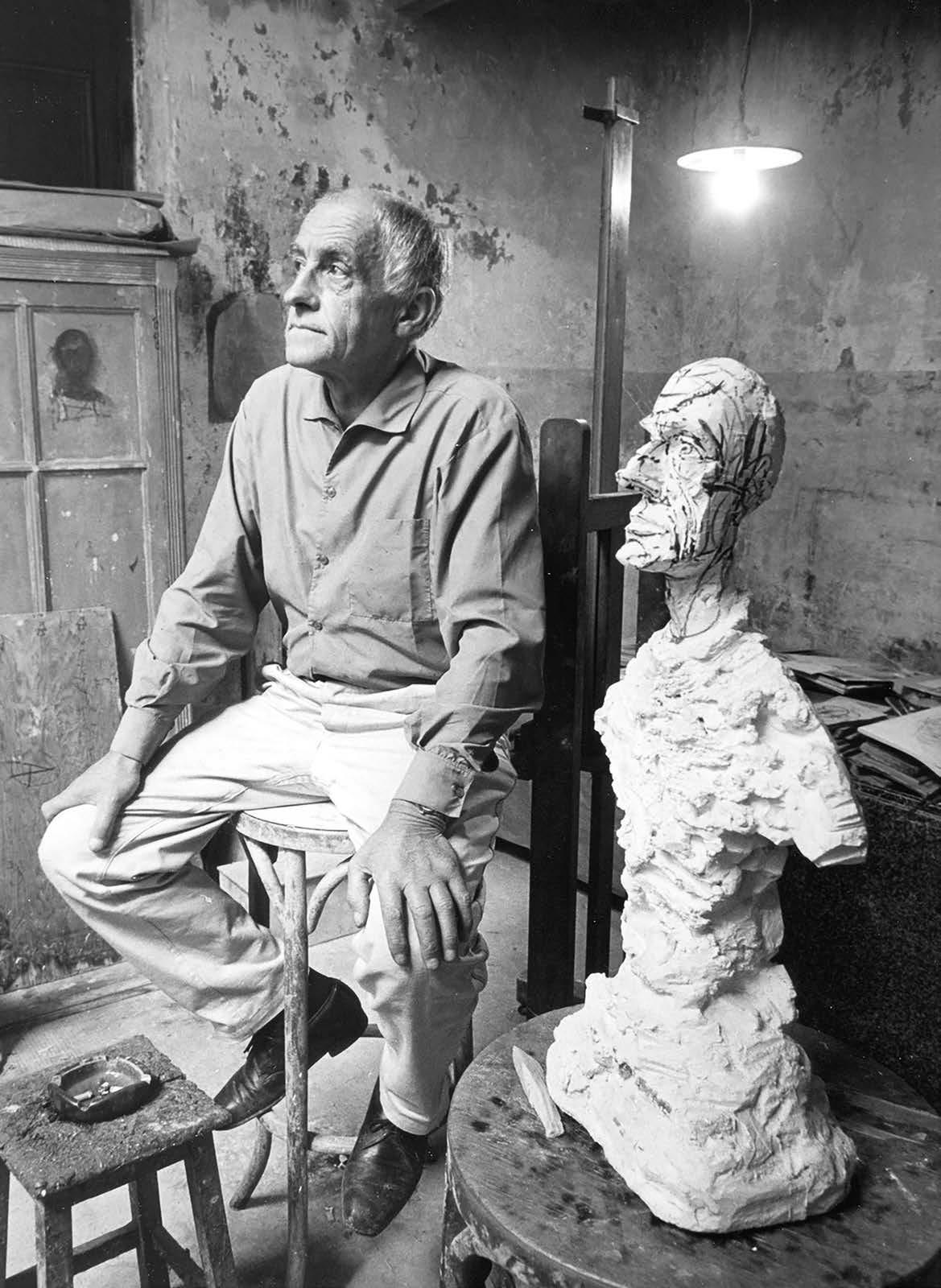

Constantinos Karpidas (known to everyone as Dinos) was a highly successful engineer from a middle class family of Greek engineers and merchants. An eccentric character with a keen intellectual wit and poetic sensibility, Dinos belonged to the new jet-set; an international circle where aristocratic tradition met the avant-garde. Pauline’s own artistic nature and innate vivacity saw her flourish amongst this creatively inclined and well-heeled crowd. With great consequence, it was this milieu that brought Pauline and Dinos into the orbit of the notoriously outré and gifted art dealer, Alexander Iolas.

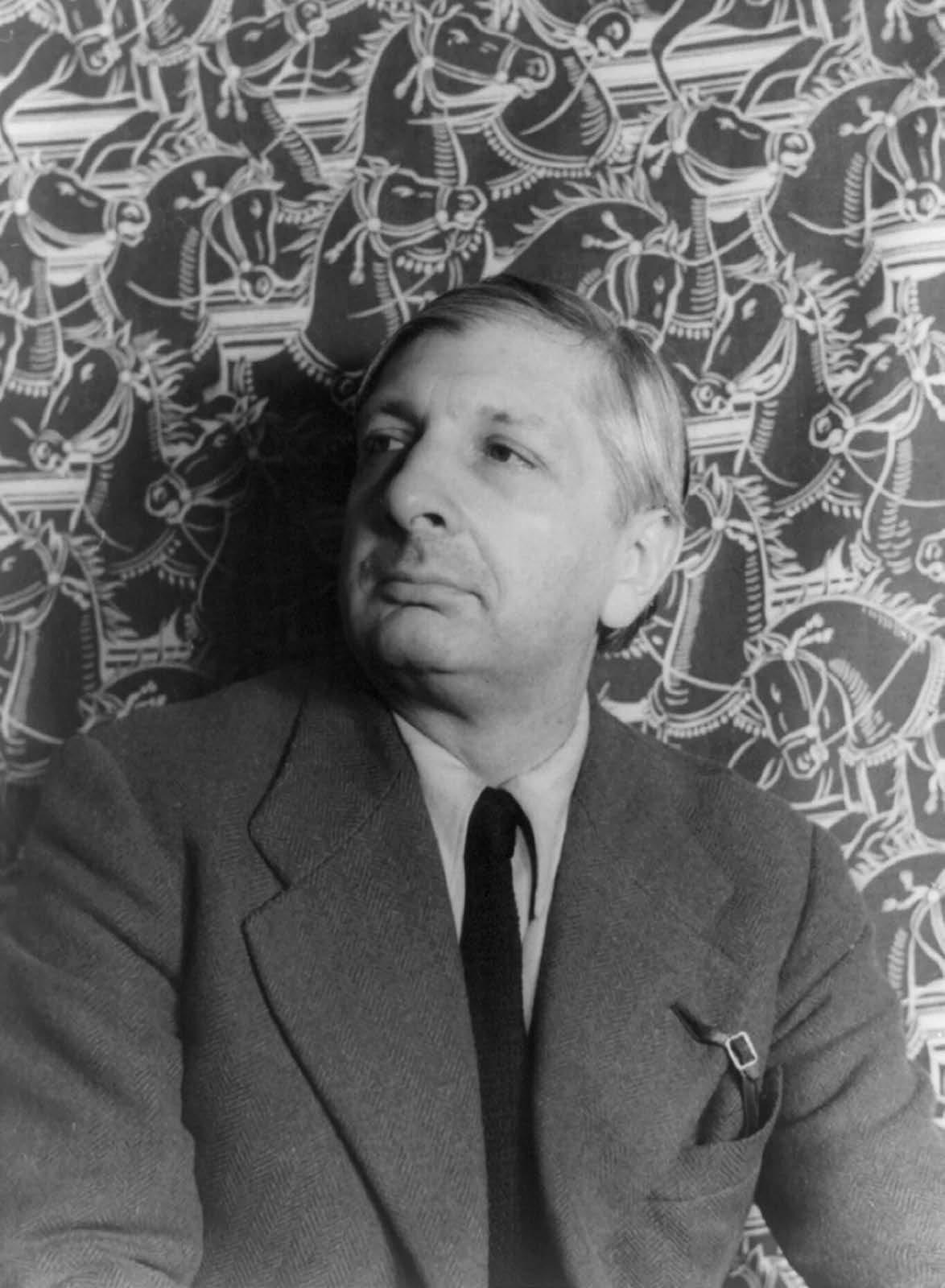

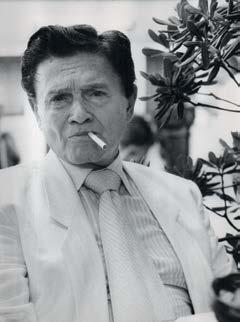

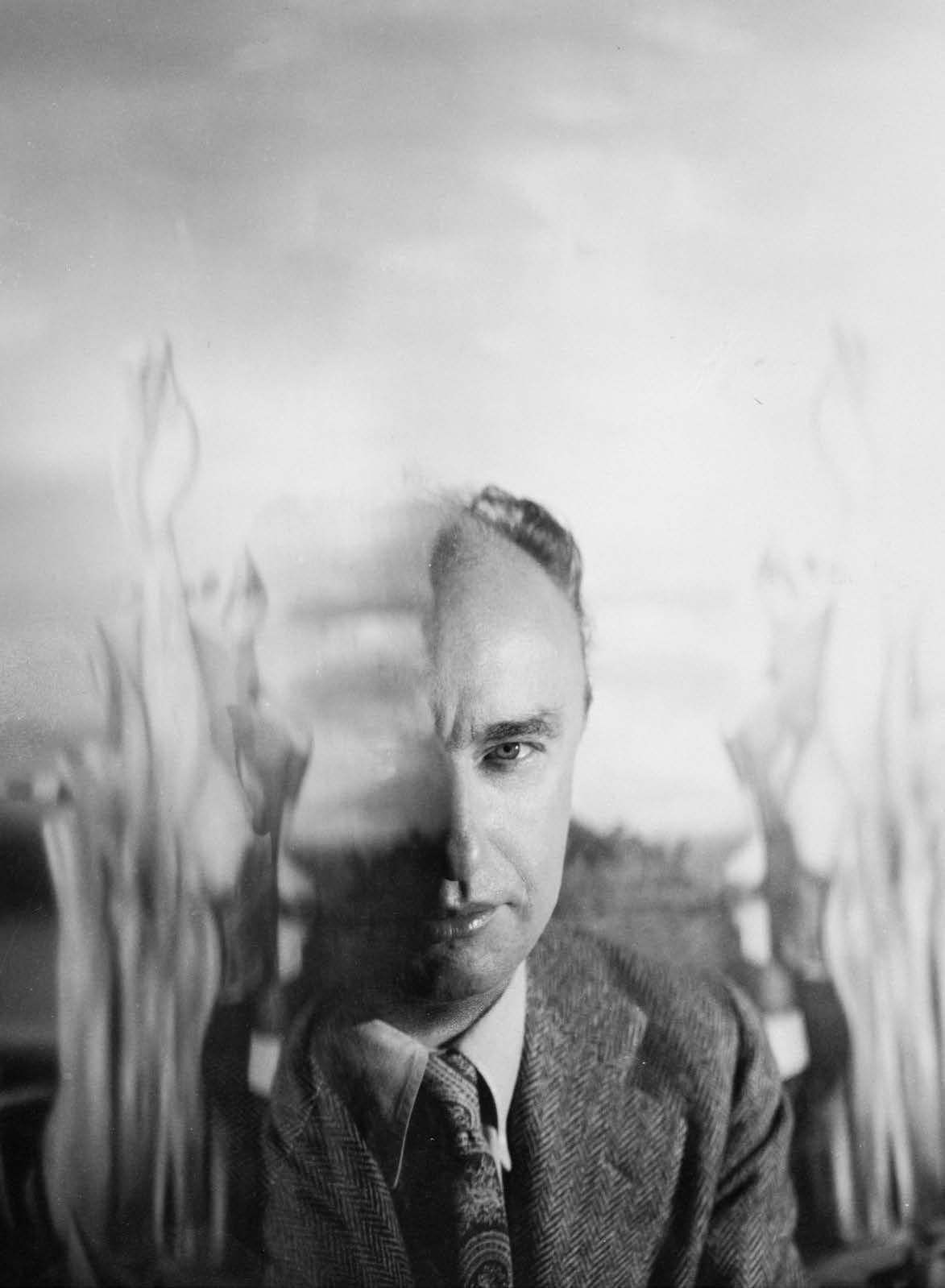

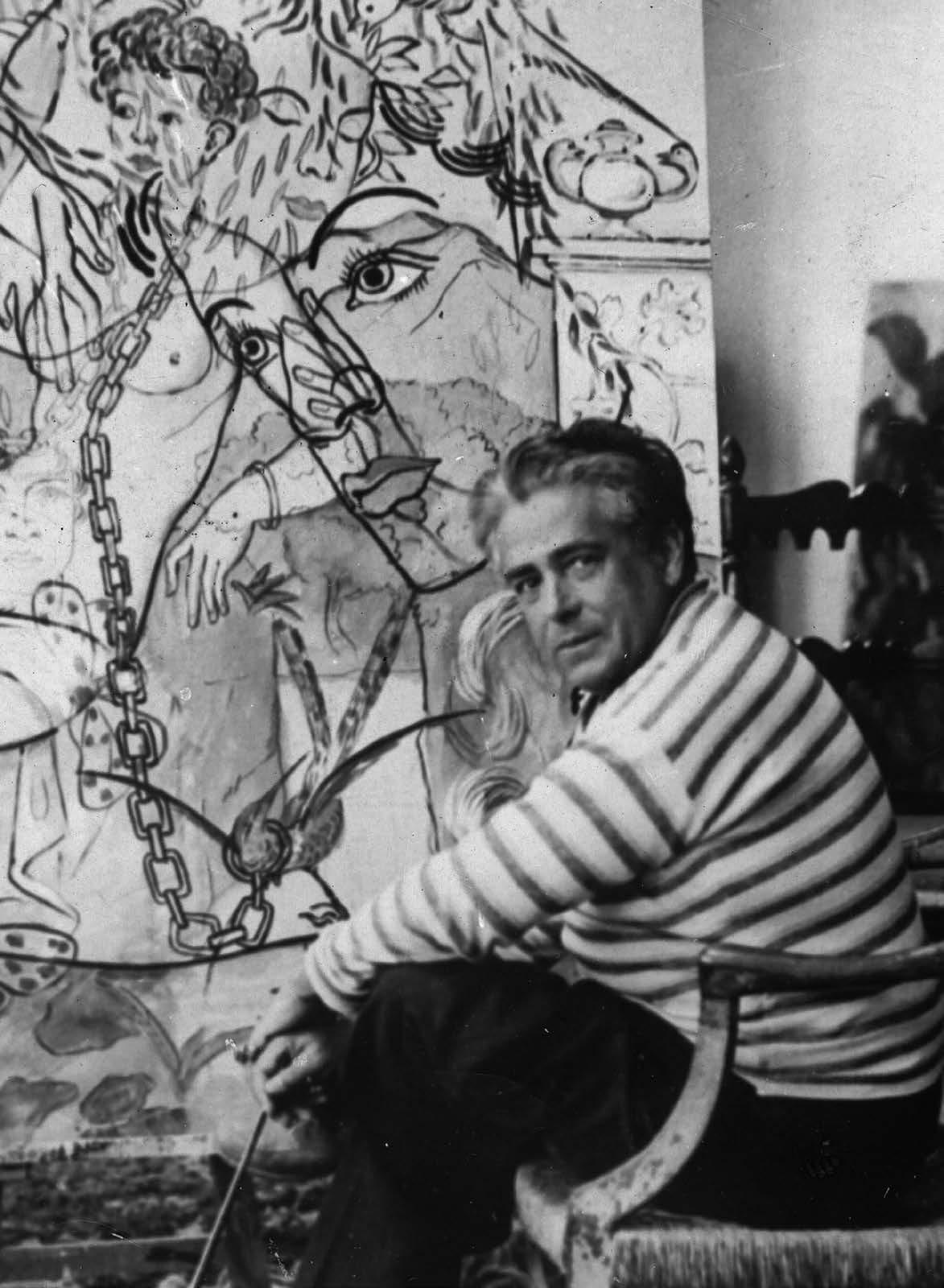

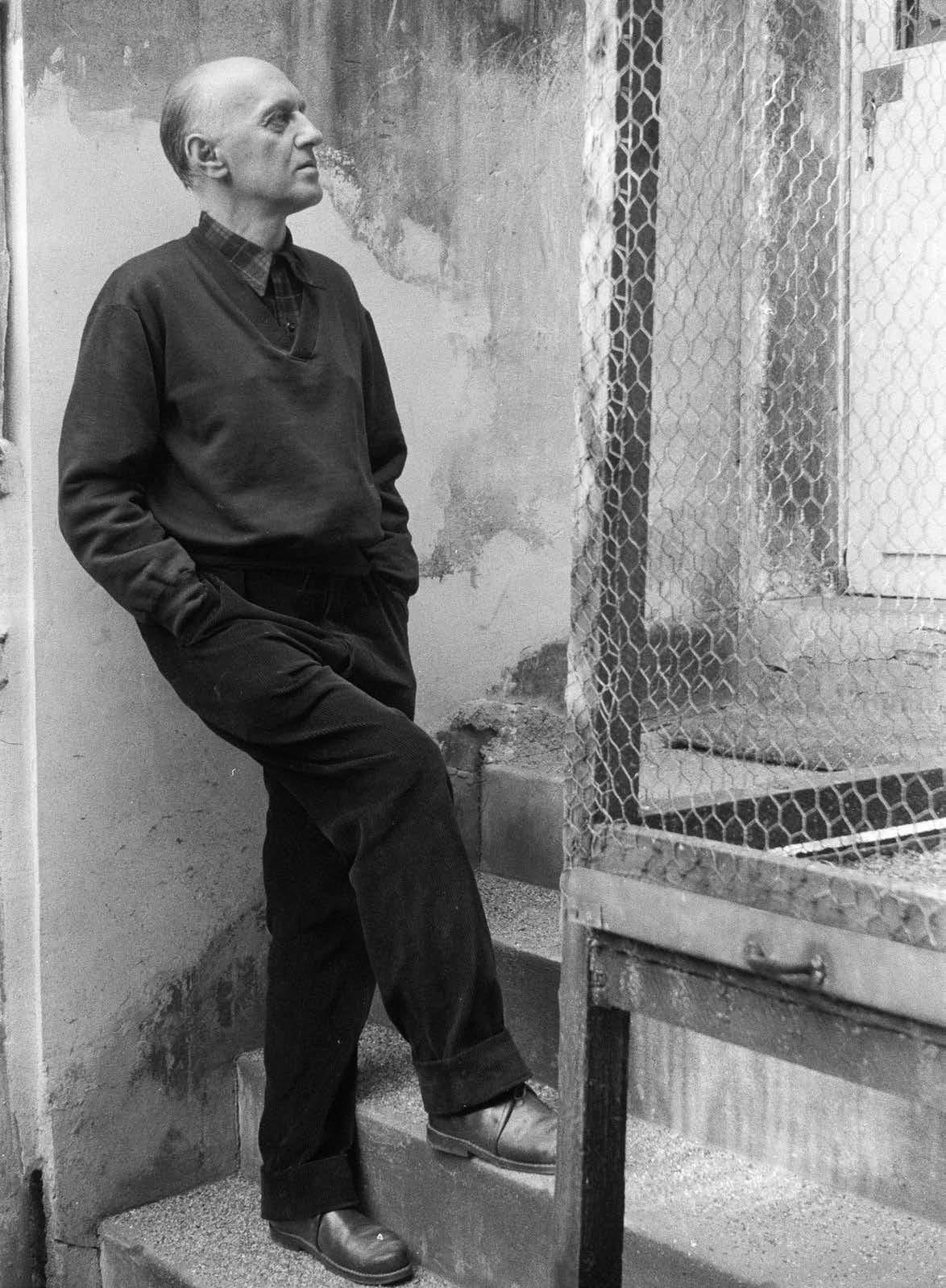

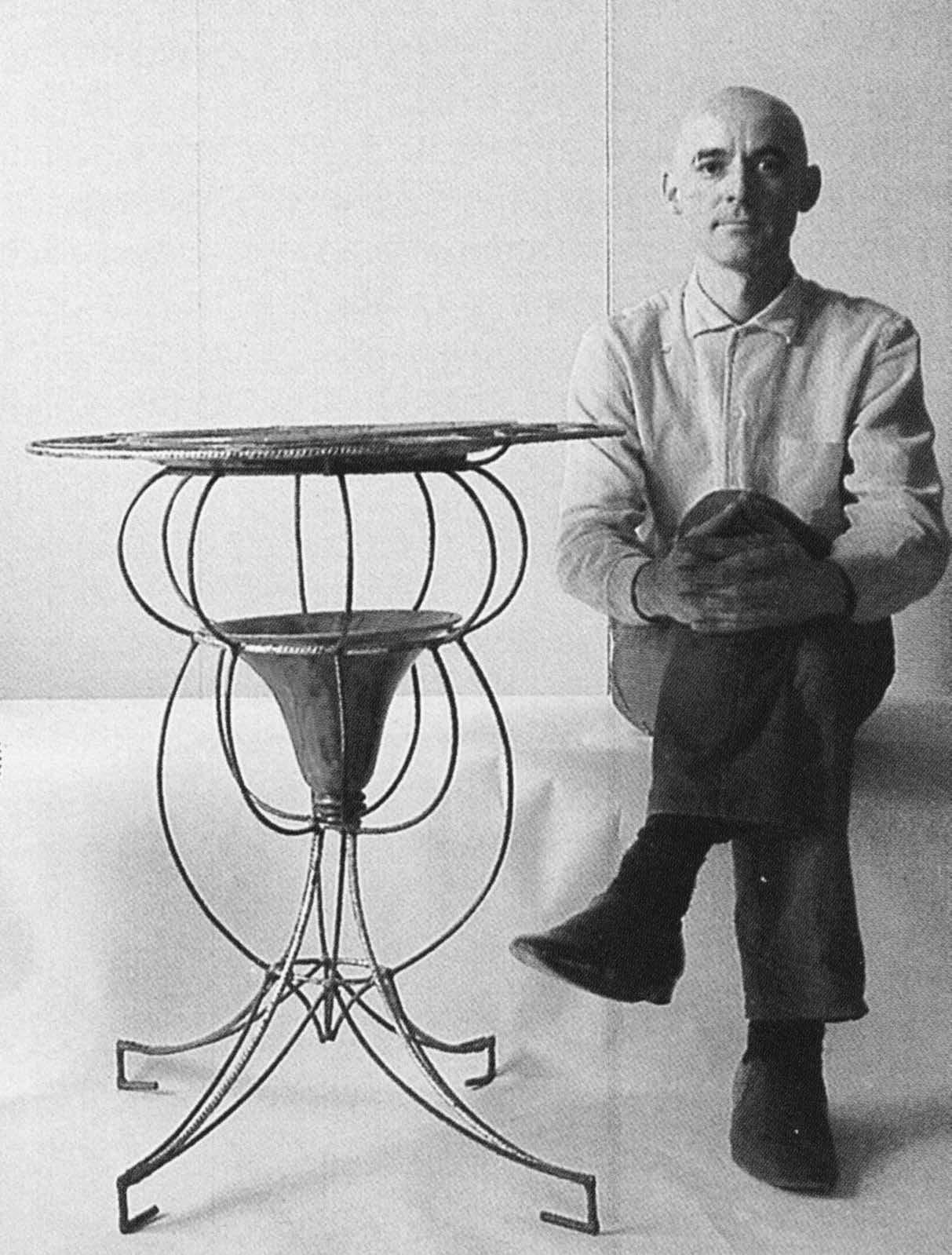

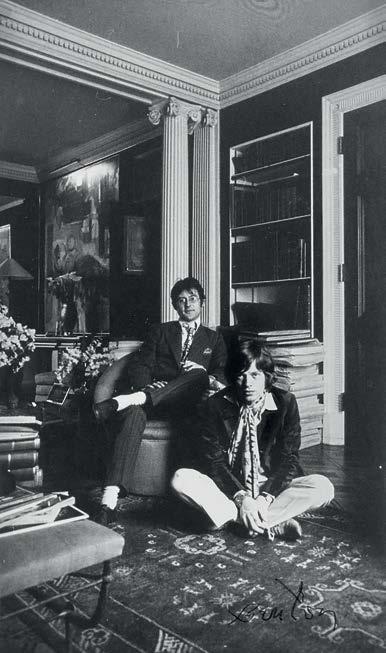

With his furs and fondness for provocative costume, Iolas was a sartorial spectacle whose natural proclivity as a performer commanded the attention of everyone around him. He could hold court in five languages and cast an entire salon under his spell; he knew everybody who was anybody, and was as wonderfully chaotic and mercurial as he was charismatic and brilliant. Indeed, Iolas’s theatricality was only equal in measure to the scrupulous conviction with which he supported his artists and the generosity he showed his exclusive coterie of loyal friends and collectors. Boasting a ledger that ran the gamut of great twentieth century art from Picasso, Ernst, Magritte and Dali, to Les Lalanne, Fontana, Ruscha, Rauschenberg and Warhol, Iolas’s legacy today places him as the most important art dealer of the second half of the twentieth century. It is no exaggeration to say that it was his undeniable influence that charmed the Karpidas Collection into being.

Iolas was born in the Egyptian city of Alexandria to wealthy Greek parents. Alexandria of the fin de siècle was a place of fabled cosmopolitan sophistication and a poetic cultural heritage; a fitting origin-story for an individual who welcomed drama of mythological proportion and embodied exotic cultural fluency. The son of prosperous cotton-merchants, Iolas spurned the family business and instead went on to enjoy a highly successful first career as a ballet dancer in both Europe

and America. It was not until the mid-1940s that Iolas came to art in a second act that was even more brilliant than the first.

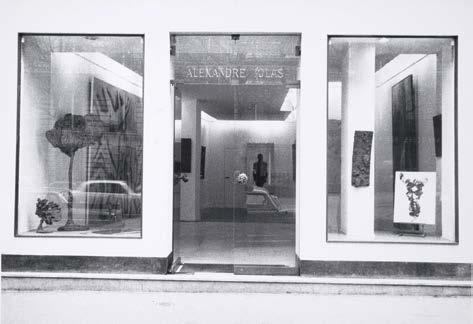

In 1945 the Hugo Gallery opened in New York— later renamed Alexander Iolas Gallery—and from here Iolas established an exceptional reputation with exhibitions of the European avant-garde. Surrealism was Iolas’s first great love; taking on the mantle after Julien Levy—the eminent dealer who introduced New York to the Surrealists in the 1930s—Iolas staged

an extraordinary programme, showcasing work by the Surrealist greats Max Ernst, René Magritte, Salvador Dali, Dorothea Tanning, Giorgio de Chirico, Man Ray, Leonora Carrington, Victor Brauner, and Leonor Fini among many others. With the art world’s good and great at his fingertips, Iolas had a hand in forming many of the most important private art collections of the 20th Century. It was through Iolas that Dominique de Menil, no less, developed her great eye as a collector.1 Tellingly, the aforementioned rollcall reads as a star-studded framework that is today reflected in the masterpieces on view at The Menil Collection in Houston; a list and level of quality that would moreover come to form the core of Pauline’s own collection. By the time Pauline and Dinos had properly befriended him in the mid-1970s, Iolas had spent almost three decades building collections and cementing the careers of so many major artists via an ever expanding trans-Atlantic fleet of galleries from Paris and New York, to Geneva, Milan, Madrid and Athens. Decades before Larry Gagosian launched his gallery empire, Iolas had already established the model.

Iolas did not so much consider himself an ‘art dealer’ in the sense of chasing monetary success through art trades (though his opulent lifestyle would suggest otherwise); he was driven instead by an utter belief in, and passion for, the work of his artists. This was a principle he also applied to his collectors: Iolas selected his clients on the basis of their character, not the depth of their pockets. In 1965 for Paris Vogue, Iolas described this very attitude to art historian Maurice Rheims: “I am not an art dealer just to sell paintings. My collectors are friends, friends that I make fall in love with what I do, with what I see… I think all of my friends have a divine je ne sais quoi about them that attracts me to them. They have something of me, something that plays into my culture. I adore people that have the sublime, the divine about them… Only those who are gifted with a poetic sensibility are my friends; I love to be around them because they carry the poetry of the world with them. What I want in life, because now I no longer want to dance, is to bring poetry through my paintings. Earning money, that’s not my goal. I believe in the preponderance of the spirit.”2 By the mid 1970s, having already achieved so much, the tenured gallerist was in the process of winding down his activities. After almost 30 years spent on the go between his galleries in New York and Europe, Iolas looked to ‘return’ to Greece and retire at his newly completed vast marble mansion built on family land just outside of

Athens. That Iolas effectively brought himself out of retirement for Pauline and Dinos is a true testament to the kindred spirit of their relationship and the seriousness of Pauline’s ambitions.

Dinos first met Iolas at a cocktail party in 1973; however, it was one year later, when Iolas was introduced to Pauline for the very first time, that the beginning of a great friendship, mentorship, and collaboration truly began. Pauline’s memory of that first meeting is marked both by eccentricity and a sincere resolve at the prospect of putting a collection together. Explaining her first impressions of Iolas at his mansion in Agia Paraskevi, Pauline recalled: “As I walked in, I just could not believe my eyes, this whole baronial hall was filled with all the great masterpieces, and I had no idea who they were; it was Max Ernst, Tanguy, Picasso, Dorothea Tanning, Man Ray, Yves Klein, all the greats, and I just said wow!… The next morning, I got in the car and went running round, and there he was, having his hair dyed, along with his sort of houseboy who was just five foot tall… I said to Iolas ‘Get up, we have to talk’. And he asked ‘We have to talk?’, and he made this wonderful flick of his white towel that turned it into a sort of Turkish turban… So that was the start of a great journey with a great mentor; he was the one who said, ‘You must train your eye, you must visit every museum in every city, you must read and understand about the twentieth century.’ …As Iolas said to Dinos, it will take ten years to put ten masterpieces together. And it did take ten years to put those ten masterpieces together… it wasn’t just about buying a work of art instantly. Instead you discovered it, you pondered on it, you asked questions about it… As Iolas said to me, ‘You know, I don’t get out of bed to buy one painting.’”3 And that he did not: together they would assemble an extraordinarily broad yet intrinsically linked compendium of outstanding pieces via the most important dealers, galleries, and auctions of the day.

Pauline and Dinos became part of art world high-society: alongside Iolas they mixed with a host of influential characters from artists, gallerists and intellectuals to socialites, philanthropists and aristocrats. There was Pierre Matisse and his wife Teeny Duchamp, Max Ernst and Bill Copley, Edward James and John Richardson, Jan Krugier and Paloma Picasso, Nan Kempner and Sao Schlumberger; they met Peggy Guggenheim and Dominique de Menil; were well acquainted with Andy Warhol and his Factory stalwarts Fred Hughes and Bob Colacello; and became great personal friends with Les Lalanne and Iolas’s righthand man Andrė Morgues who encouraged Pauline to wear

1 “I was very lucky because I learned also from a great dealer, Alexander Iolas… he had a great eye – and I would trust his judgement. I had to learn. When he told me, ‘Take it, you have to have it,’ like the Metaphysical by de Chirico, he just told me to take it and I trusted his eye – his judgement… I bought it on his word, on faith…” Dominique de Menil, quoted in Exh. Cat., New York, Paul Kasmin Gallery, Alexander the Great: The Iolas Gallery, 1955-1987 2014, p. 44

2 Alexander Iolas in conversation with Maurice Rheims, Paris Vogue, August 1965, reprinted in Exh. Cat., New York, Paul Kasmin Gallery, Alexander the Great: The Iolas Gallery, 1955-1987 2014, pp. 34-42

3 Pauline Karpidas, “Alexander Iolas”, interviewed by Adrian Dannatt, in ibid., pp. 78-79

couture and introduced her to Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé. Under Iolas’s instruction Pauline attended the right events, set to work devouring books on art and philosophy, and saw every major exhibition. For Pauline, it was the beginning of a great schooling that would last a lifetime.

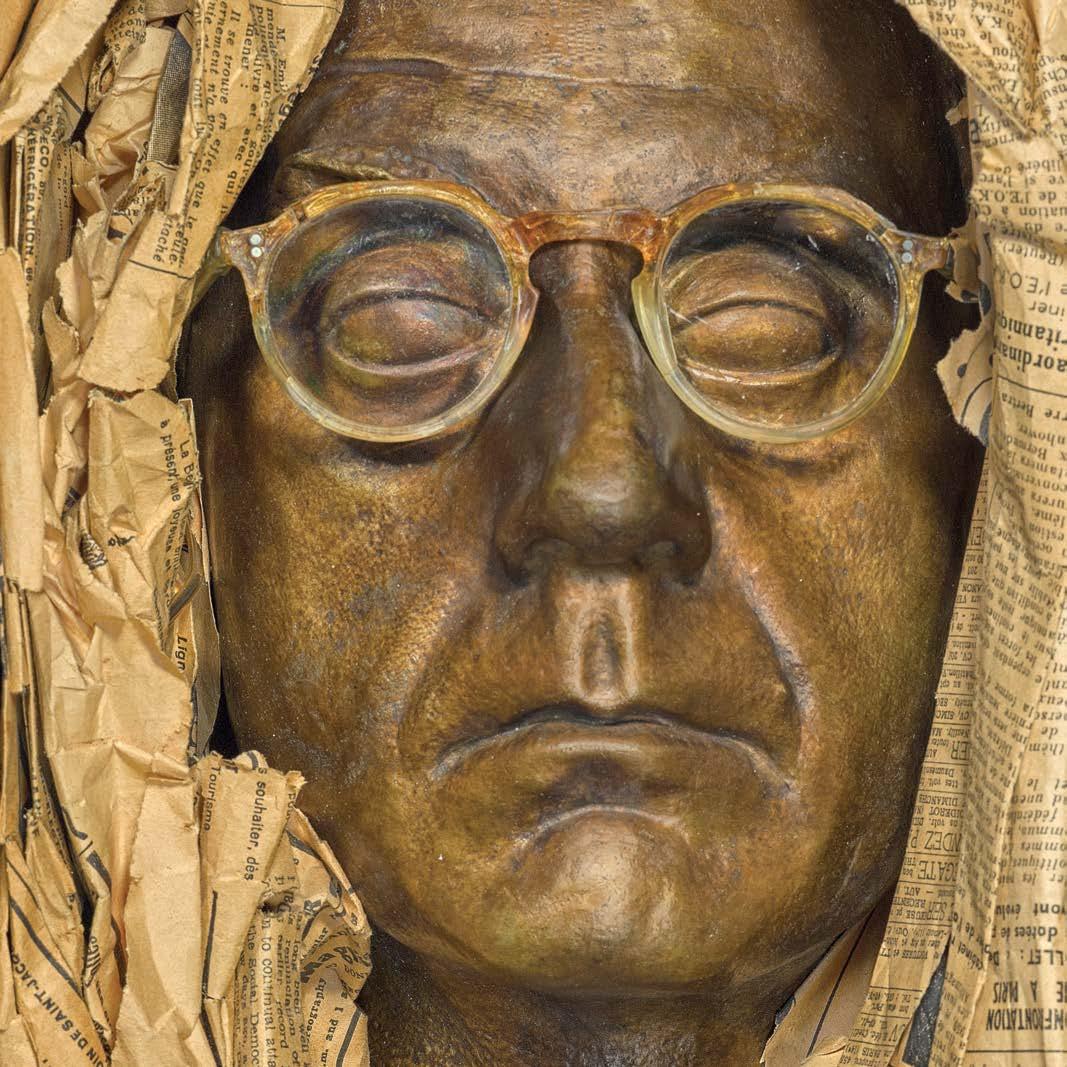

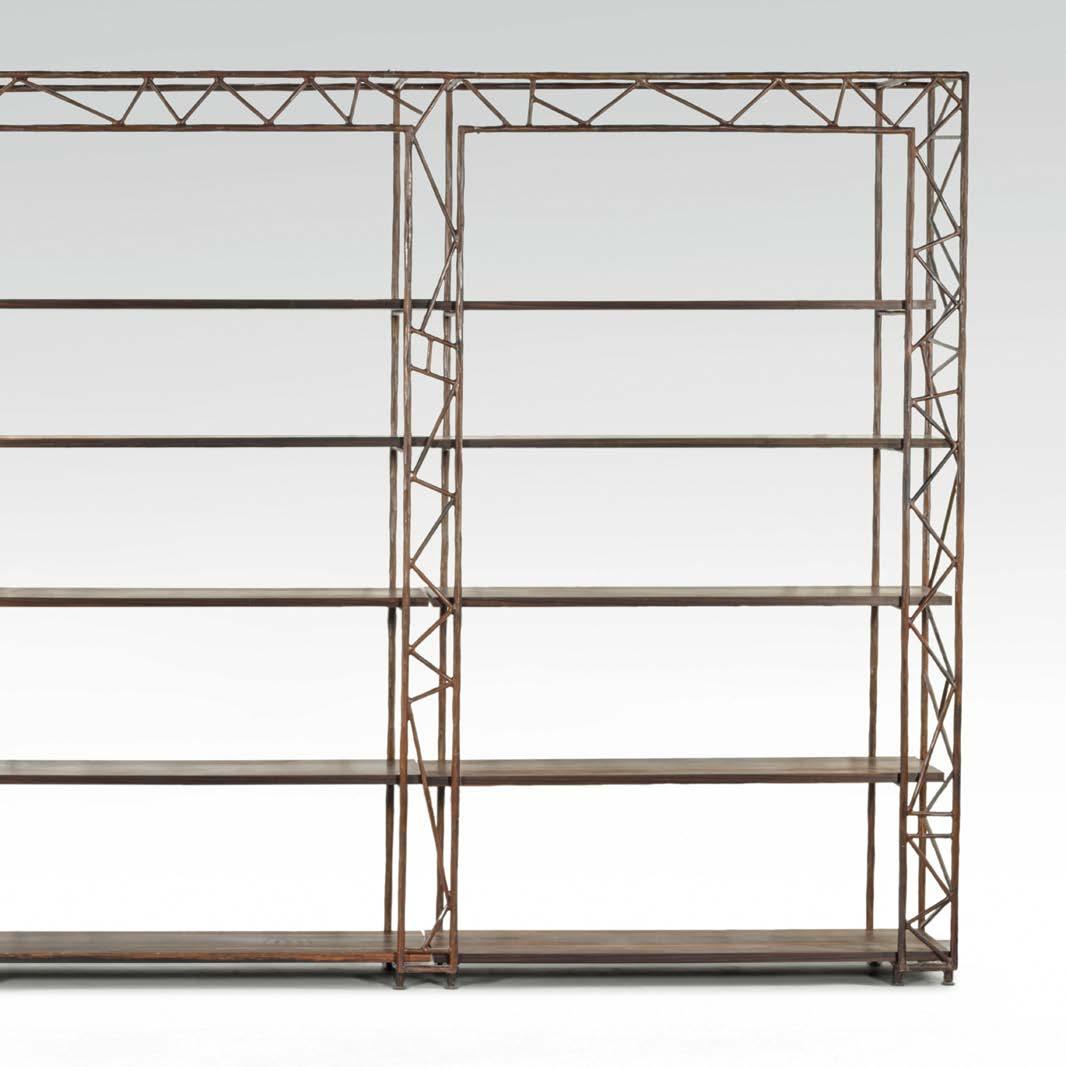

Aside from the collection itself, nowhere is this intellectual journey more evident than in the stacked shelves of Pauline’s library at The Lancasters in London. A veritable wunderkammer of art objects sat nestled amongst important tomes spanning philosophy, psychoanalysis and art history; books that show signs of wear and tear, read cover-to-cover in support of a truly intellectual life. Sat amongst these books for many years, Claude Lalanne’s copper bust of Pauline provided an ever-meditative presence. Bearing an expression of repose and calm, Pauline’s eyes are closed and peaceful as though immersed in a dream;

with her hair transformed into a veil of leaves she is both Daphne in metamorphosis and Athena the sage; a mythological embodiment of both transformation and wisdom.

The very sagacity that brought the collection into being—this mixture of dedication, trust in Iolas, and an innate eye for quality—is no less underscored by the rich history that accompanies nearly every piece. To this end, not only did Iolas oversee acquisitions directly from artists or via notable dealers, he also encouraged Pauline and Dinos to look to auction. With the economic boom of the 1980s came the first great spike in the art market. The value of important masterpieces began its steep ascent, and in turn, major 20th Century works of art were beginning to come to auction. Ever with his finger on the pulse, Iolas directed Pauline to the salesrooms of Sotheby’s and Christie’s as they presided over once-in-a-

lifetime presentations of critically important private collections and estates. It was at the former in 1975 that Pauline made a lasting impression on the great Sotheby’s expert Michel Strauss. In his memoirs, Strauss recalled their meeting with great fondness and in some detail; as the following words convey, this was the beginning of a friendship that would last a lifetime:

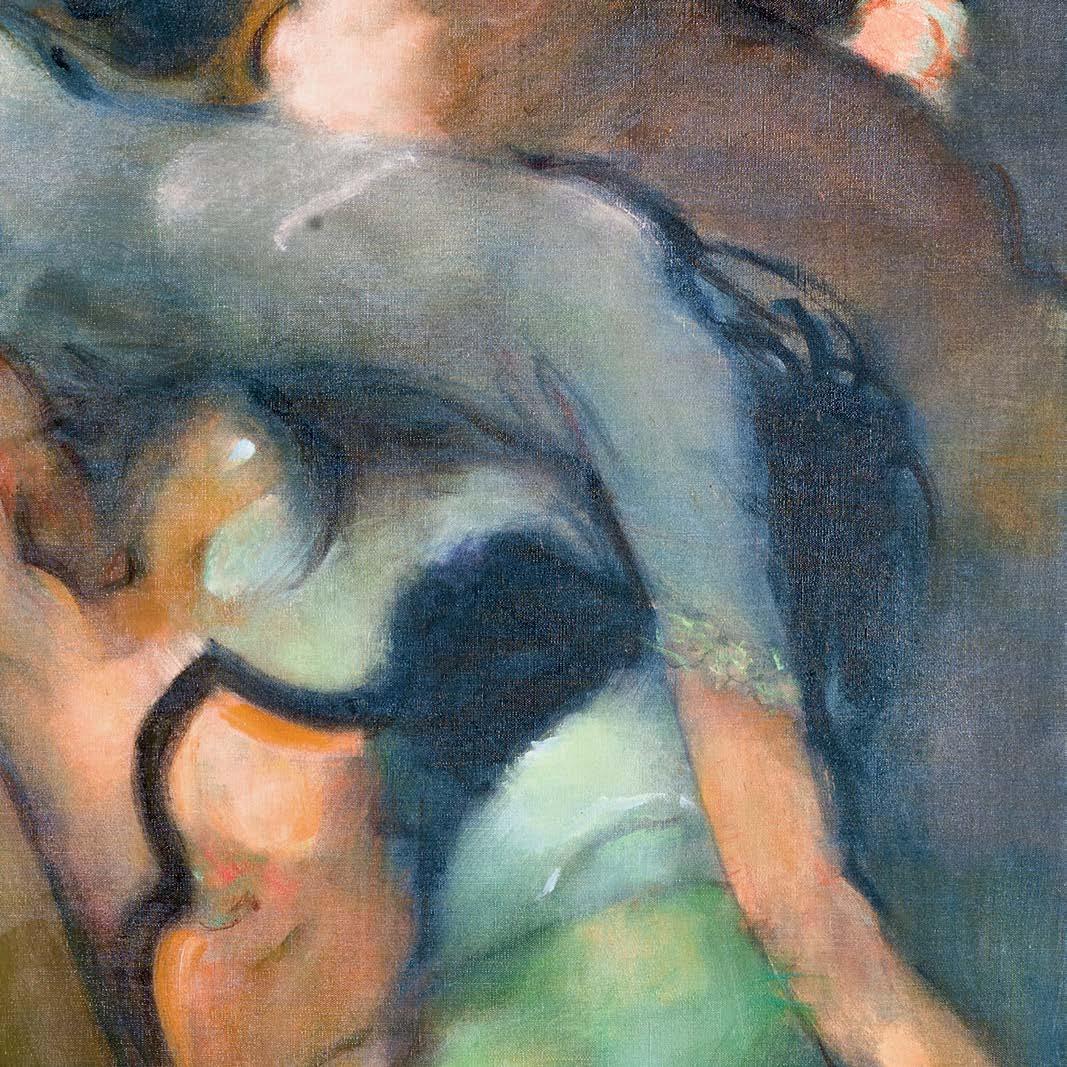

“One afternoon I happened to be in the gallery when a young woman came in from the street, dressed in a T-shirt and jeans and asked whether she could see the pictures as she had just read about the sale in the press. She introduced herself as Pauline Parry and I was, of course, delighted to show them to her, influenced in part by the fact that she was a very pretty and friendly girl. I could see that she loved looking at them and hearing some of the stories I was telling her about the collection. As she was leaving the building she asked if she could have two tickets for the sale. My immediate thought was that as so many people were going to want to attend and seating was limited in the saleroom, I couldn’t just hand out tickets to pretty girls who took my fancy. I mumbled something noncommittal and to fob her off, asked her where the tickets should be delivered when they became available on the day before the sale. To my surprise she gave as an address 5 Grosvenor Square. Intrigued, I gladly sent her the tickets. She turned up for the sale looking very glamorous in evening dress and magnificent diamonds, accompanied by an older man. They proceeded to buy two of the lots: a Camille Pissarro of a peasant woman and her child sitting in an orchard for £65,000 and a beautiful painting by Edgar Degas of two dancers in bright yellow tutus waiting in the wings to come on stage which they bought for £100,000.

A few years later Pauline married Dinos Karpidas, her companion at the Kahn-Sriber sale. He had already been buying some important works from his friend and fellow Greek, Alexander lolas, the famous, flamboyant dealer of Surrealism and the painter René Magritte in particular. Iolas had sold him several important late paintings by Picasso in the early 1970s at a time when few people understood the importance of the late work. Pauline soon plunged herself into that world and, with all the passion and knowledge she could muster, she subsequently became one of the great collectors of Picasso, Surrealism and cuttingedge Contemporary Art.”4

As Strauss recalls, Pauline and Dinos became a force to be reckoned with on the auction circuit, and, over the course of the next two decades, they would play a crucial role in some of the most prestigious events in auction history.

Offered on 5th November 1979 at Sotheby’s Parke Bernet, New York, The William N. Copley Collection presented the largest private assemblage of Surrealist

art in American hands. Bill Copley (whose artistic moniker was CPLY) was a New York born artist, gallerist, writer, and patron who amassed a substantial collection via his association with the Surrealists. For the Sotheby’s sale, Copley parted with a majority of the works he had acquired between 1947 and the mid-1970s in a record-breaking auction that, at the time, achieved the highest total on record for a private collection sale in the United States. It was from this sale that Yves Tanguy’s Paysage au nuage rouge, Giorgio de Chirco’s La Guerra and Max Ernst’s Portrait d’Appollinaire were crucially acquired. Following Copley, Pauline truly immersed herself in the world of auction. In 1981, in a feat of saleroom bravery and nerve, Dalí’s Surrealist icon Le Sommeil became a cornerstone of the Karpidas Collection. This painting—among the most famous and important artworks of the Surrealist movement - first belonged to the poet, esteemed Surrealist advocate and patron, Edward James (1907-84). In 1981 when James’s collection was presented at Christie’s London, this painting graced the sale catalogue’s front cover. As soon as this masterpiece arrived on the auction block on the evening of 30th March, a fierce bidding war ensued. The National Galleries of Scotland competed strongly for the painting, however, it was the Karpidas’ who won the battle that night and this Surrealist treasure remained with Pauline for many years in London. Dalí’s Messanger dans un paysage palladien of 1936—with its playful gilt frame encasing an ink drawing on pink paper—also originated from

the same collection: this piece had resided in James’s bedroom at the Surrealist-inspired gesamtkunstwerk of Monkton House, a hunting lodge in West Dean renovated under the auspices of Dalí himself.

The Karpidas’s participation as auction buyers would continue with aplomb over the next decade or so. In reviewing the provenance of each piece, the collection as a whole represents a who’s who of the first major single-owner collection auctions in art market history. Picasso’s Violon was acquired from the Andre Meyer sale (Sotheby’s New York, November 1980); four works on paper by Max Ernst and Man Ray came from the single owner sale of the great Surrealist dealer Julien Levy (Sotheby’s New York, November 1981); Wols’s Vert Strié Noir Rouge came from the Hélène Anavi Collection sale (Sotheby’s London, March 1984); René Magritte’s Tête hailed from Sotheby’s sale of the artist’s studio contents (Sotheby’s London, July 1987); and Victor Brauner’s Nous Sommes Trahis was bought from the André Breton Collection (Hôtel Drouot, Paris 2003). These are but a handful of examples. Such is the calibre of this collection that almost every work’s provenance lists a rich history of names from Leo and Gertrude Stein, André-Francois Petit, and Barnet Hodes, through to Marcel Jean, Kay Sage Tanguy and Roland Penrose. Following discerning advice from Iolas, these pieces were not only acquired for their artistic merit, but also for the lives lived by the artworks themselves.

As the collection grew, Pauline became increasingly confident and her interests more mercurial and broad. At the same time as acquiring works by Magritte, Ernst, Tanguy and Dalí, Pauline and Dinos began to seek pieces by pioneering artists of the next generation. To this point, not only was Iolas the great dealer of late Surrealism, he also had a keen

eye for the most cutting edge and daring developments in post-war and contemporary art. Alongside exhibitions of earlier twentieth century masters, Iolas staged formative shows of Wols, Lucio Fontana, Jannis Kounellis, Joseph Beuys, Pino Pascali, Martial Raysse, Niki de Saint Phalle and Les Lalanne across his trans-Atlantic gallery empire. For Pauline, Iolas’s keen direction and broad remit laid the groundwork for a masterfully fluid dialogue in which the fullflowering of Surrealism’s influence is unmistakably redolent in the collection’s later twentieth century holdings. From the existential bodily manipulations of Bacon and Giacometti, to the post-war abstractionism of Wols, Roberto Matta and Cy Twombly, the spaceage forms of Fontana, through to Warhol’s iconic Pop idiom and even the most contemporary works in the collection, Iolas’s collection-building approach was broad-minded and ambitious. With Surrealism as both lodestar and nucleus, and Iolas setting the guiding principles, Pauline undertook an approach collecting and patronage that was encompassing, focused, and set to last for next 50 years and beyond.

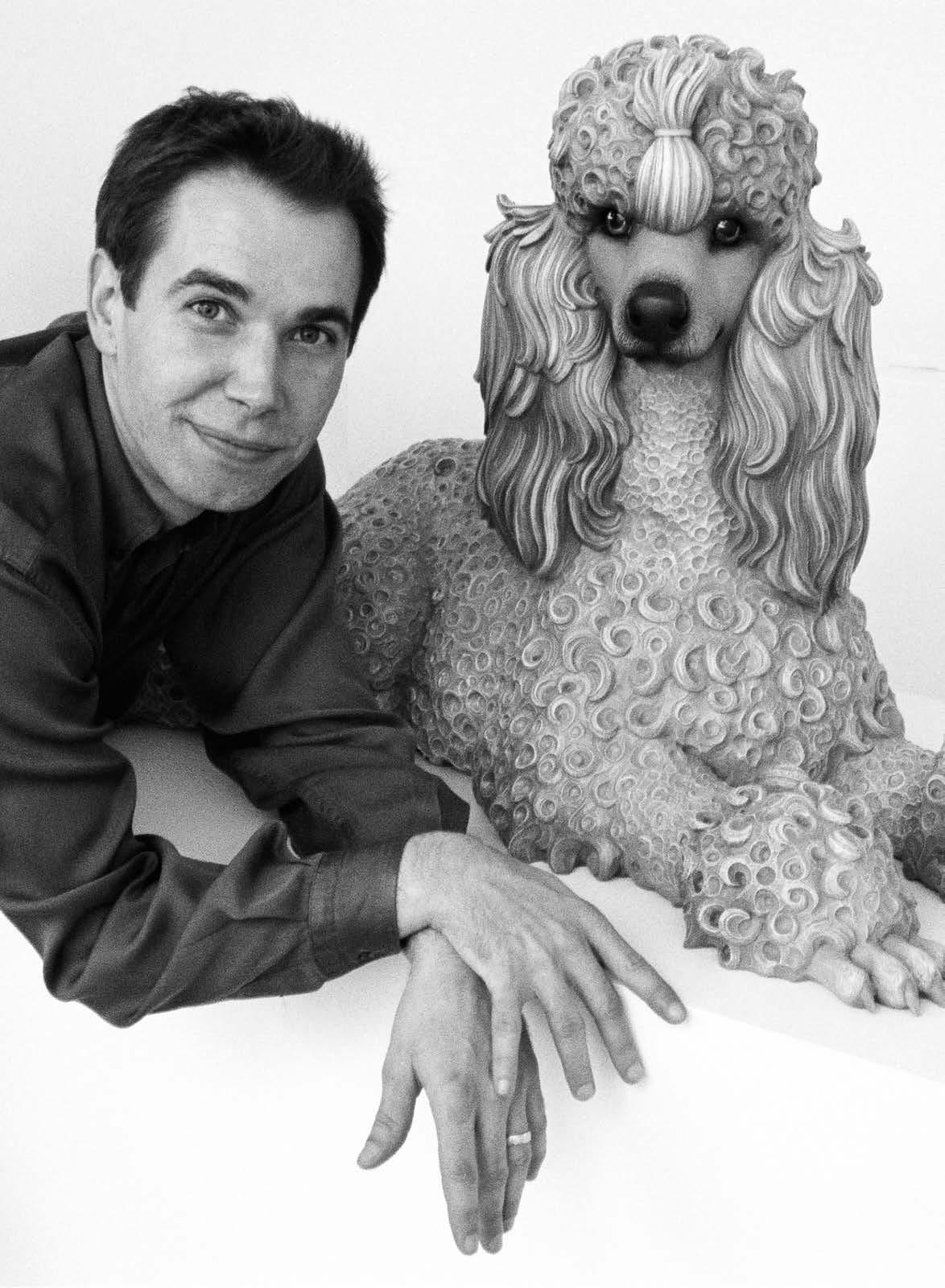

One of the most significant aspects of the collection’s trajectory, and a huge part of Pauline’s personal journey, was the influence of Andy Warhol. For Iolas, who introduced Pauline and Warhol in the late 1970s, the iconic Pop artist’s career was just as meaningful an accomplishment as his dealings with the Surrealists. Widely acknowledged as the ‘Man Who Discovered Warhol’, Iolas played an instrumental role throughout Warhol’s career: it was Iolas that gave Warhol his very first exhibition in 1952, and it was Iolas with whom Warhol collaborated to produce his very last body of work: a series based on Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper. The joint brainchild of Iolas and Warhol, these works were designed to fill an exhibition

space in the Palazzo Stelline in Milan; a building located directly across the street from Santa Maria delle Grazie—the home of Leonardo’s masterpiece. First exhibited at the very end of 1986, the subject and timing of these works would turn out to be poignantly prophetic for both artist and dealer. The Last Supper series made its debut only weeks before Warhol’s unexpected death in early 1987, and within months, this commission would also prove to be Iolas’s swan song: in June 1987 Iolas died at the age of 80. With neat symmetricality, both Warhol and Iolas’s careers began and ended with each other.

Pauline and Dinos would become friends with Warhol and familiar with the Factory and its cast of characters during the last ten years of the artist’s life. At the behest of Iolas, the couple first visited Warhol’s Factory in 1978 in order to have their polaroids taken for a double portrait commission. This meeting

would mark the beginning of a dedication to Warhol that was fuelled by intense admiration and mutual friendship. A great lover of the designs of Belperron and JAR, Pauline would find a fellow enthusiast in Warhol. The two bonded over a shared love of ostentatious jewellry and at one stage Warhol even proposed an artwork/jewellery trade after Pauline showed him some of her pieces during a dinner party at the Karpidas’s London home. It was during this same fateful evening that, encouraged by Pauline and Iolas, Warhol conceived a new group of paintings based on the wonderful suite of six Picasso works on paper acquired by the Karpidas’ from Marina Picasso in 1978.

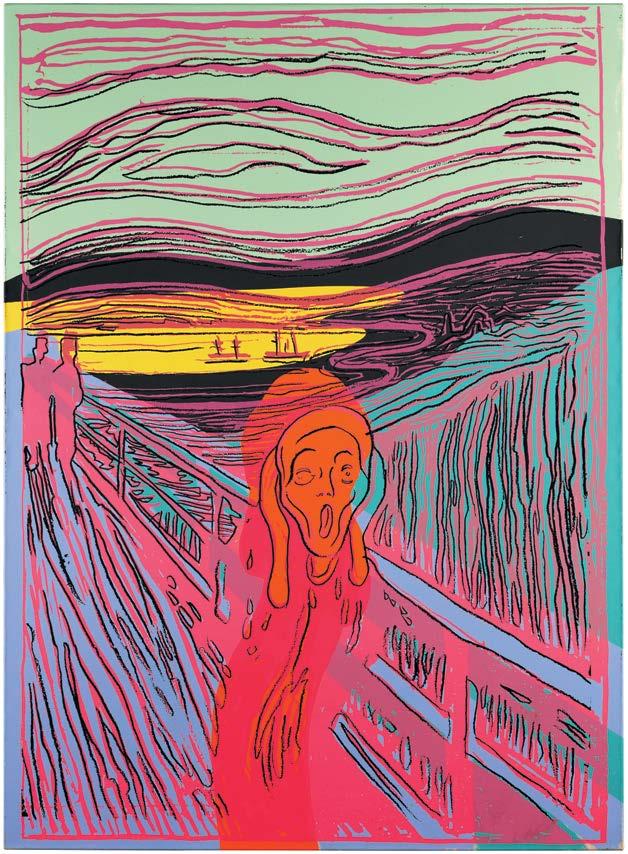

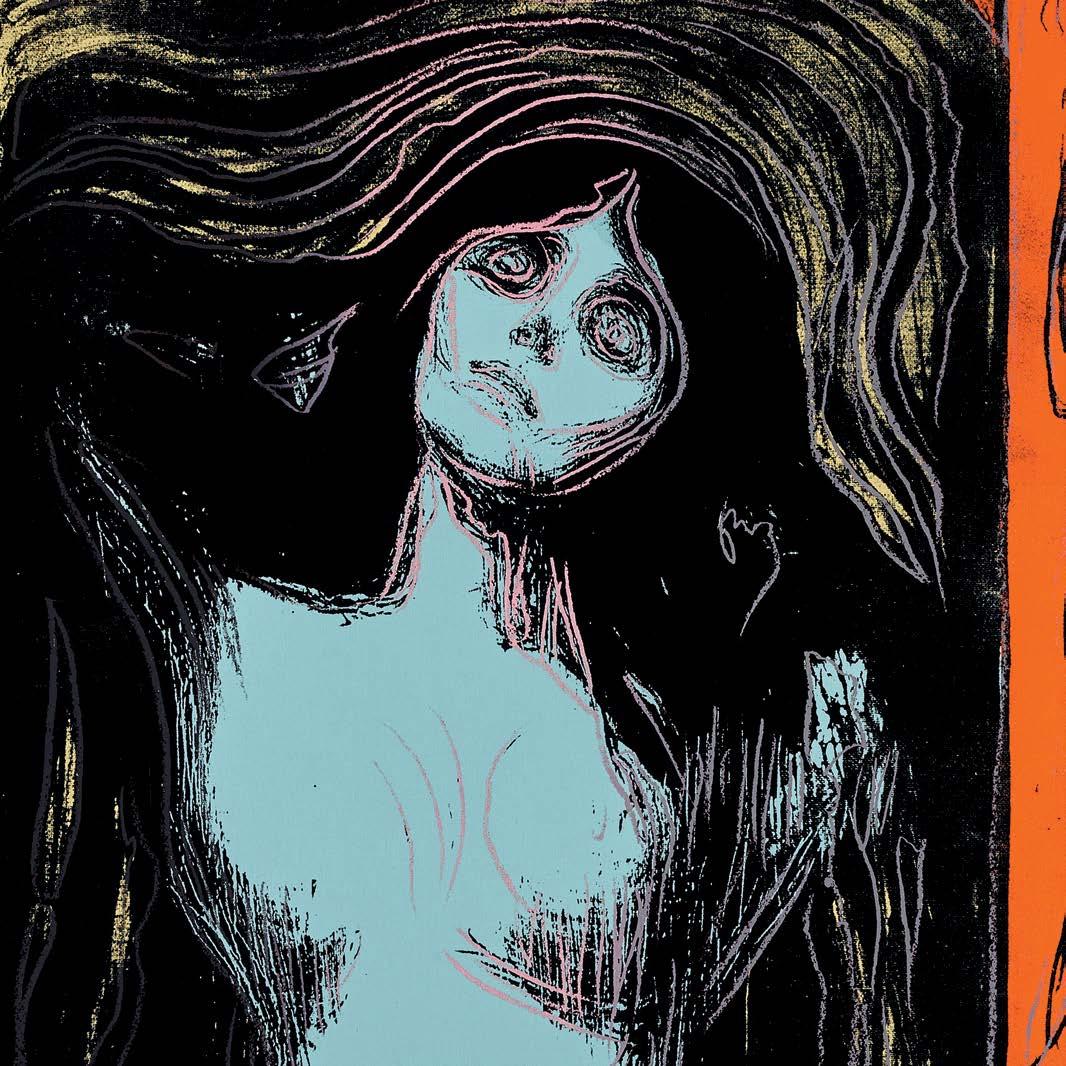

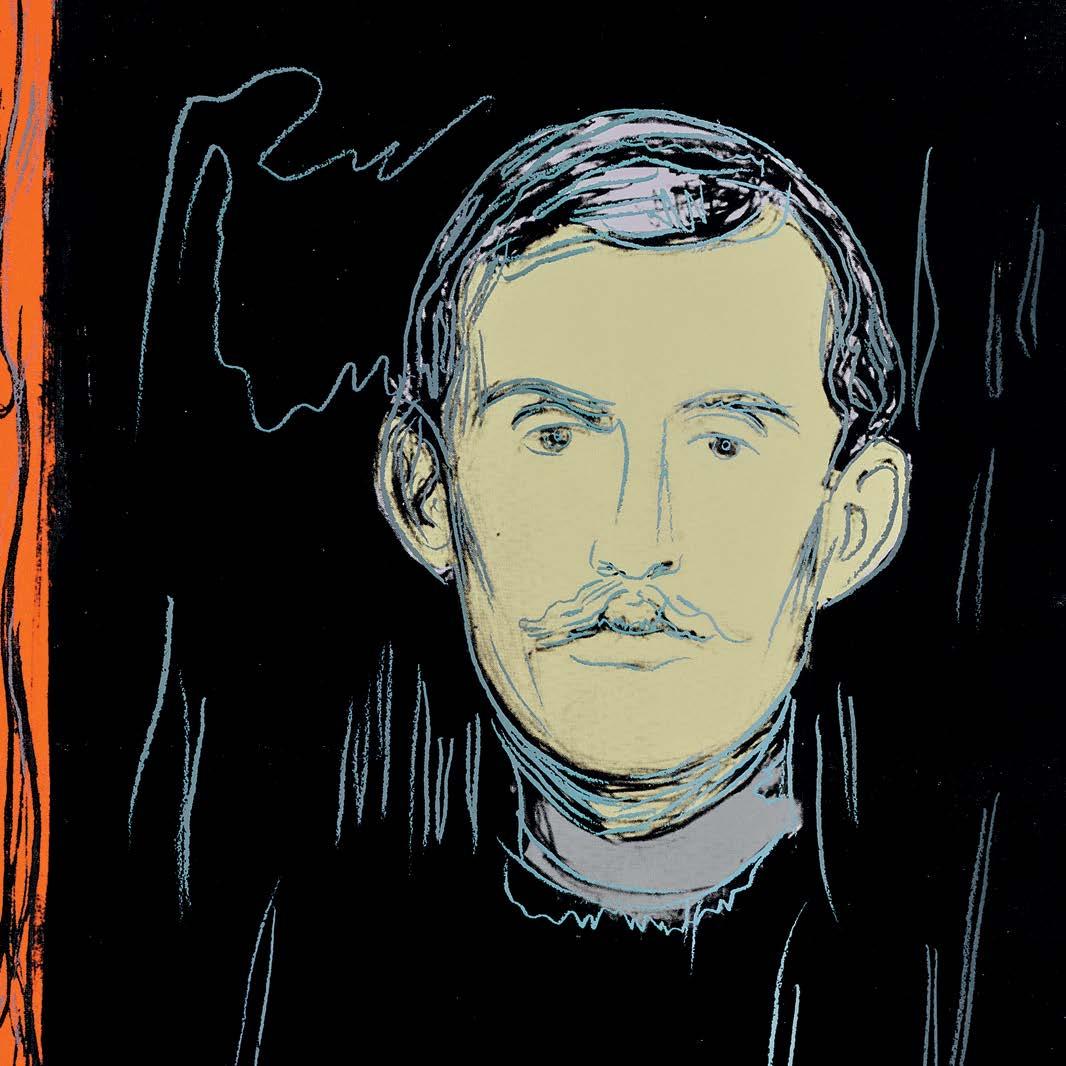

Executed in 1985 and titled, Picassoesque, Warhol’s rendition of Pauline’s suite of black and white works on paper forms a jubilant reimagining that fits seamlessly into the artist’s contemporaneous canon of ‘Art

after Art’: Warholian versions of great art historical masterpieces. Where the Karpidases had bolstered their collection by acquiring important pieces from Warhol’s 1960s oeuvre at auction—including the record-breaking acquisition of 200 One Dollar Bills (1962) at the Robert and Ethel C. Scull Collection sale at Sotheby’s in 1986— the couple were fervent advocates and astute supporters of Warhol’s late work. Portrait of Man Ray (1974) and the works after de Chirico and Munch establish a wonderful link to the earlier Twentieth Century collection-core, while the crucial inclusion of examples from Warhol’s Last Supper (1986) and the prophetic ‘fright-wig’ Self-Portraits (1986) delivered a holistic survey of Warhol’s opus that is both personal and unique to the Karpidas Collection. Of the latter, Pauline would come to play an integral role on the occasion of the 1986 Self-Portraits’ debut at Anthony d’Offay’s Dering Street gallery. Following the private view, Pauline hosted an exclusive ‘Self-Portrait Supper’ for Warhol at the Café Royal. As thanks, Pauline received an intimately scaled pink self-portrait inscribed ‘To Pauline love Andy Warhol’ on the reverse: a wonderful tribute to their friendship and pendent to the colossal white ‘fright-wig’ that Pauline later bought at auction at Sotheby’s New York in 1997.

As the 1980s drew to a close, Pauline’s mentorship with Iolas had come to an end. Following an intense programme of reading, visiting museums and galleries, meeting artists, talking to dealers, listening to Iolas’s advice and devoting her life to a pursuit of contemporary art and theory, Pauline had developed an acute eye and artistic sensibility that was entirely her own. Where Pauline’s collecting journey began in 1974 under Iolas’s mentorship, the famously selective dealer now deemed her apprenticeship complete, declaring: “Pauline, you’re on your own.”5 With an exciting next chapter ahead, Pauline looked to the very cutting edge of contemporary art and became a patron in the manner of the great Grande Dames before her, working closely with the likes of Larry Gagosian, Per Skarstedt, and Sadie Coles to build an extraordinary collection of twenty-first century art. Pauline’s prescient support of some of the most important artists of the last 20 years, alongside the wonderful exhibitions she staged on Hydra during the late 1990s and 2000s, is utter testament to this. Indeed, although the apprenticeship was over, Pauline’s intellectual journey and rich programme of patronage had only just begun.

5

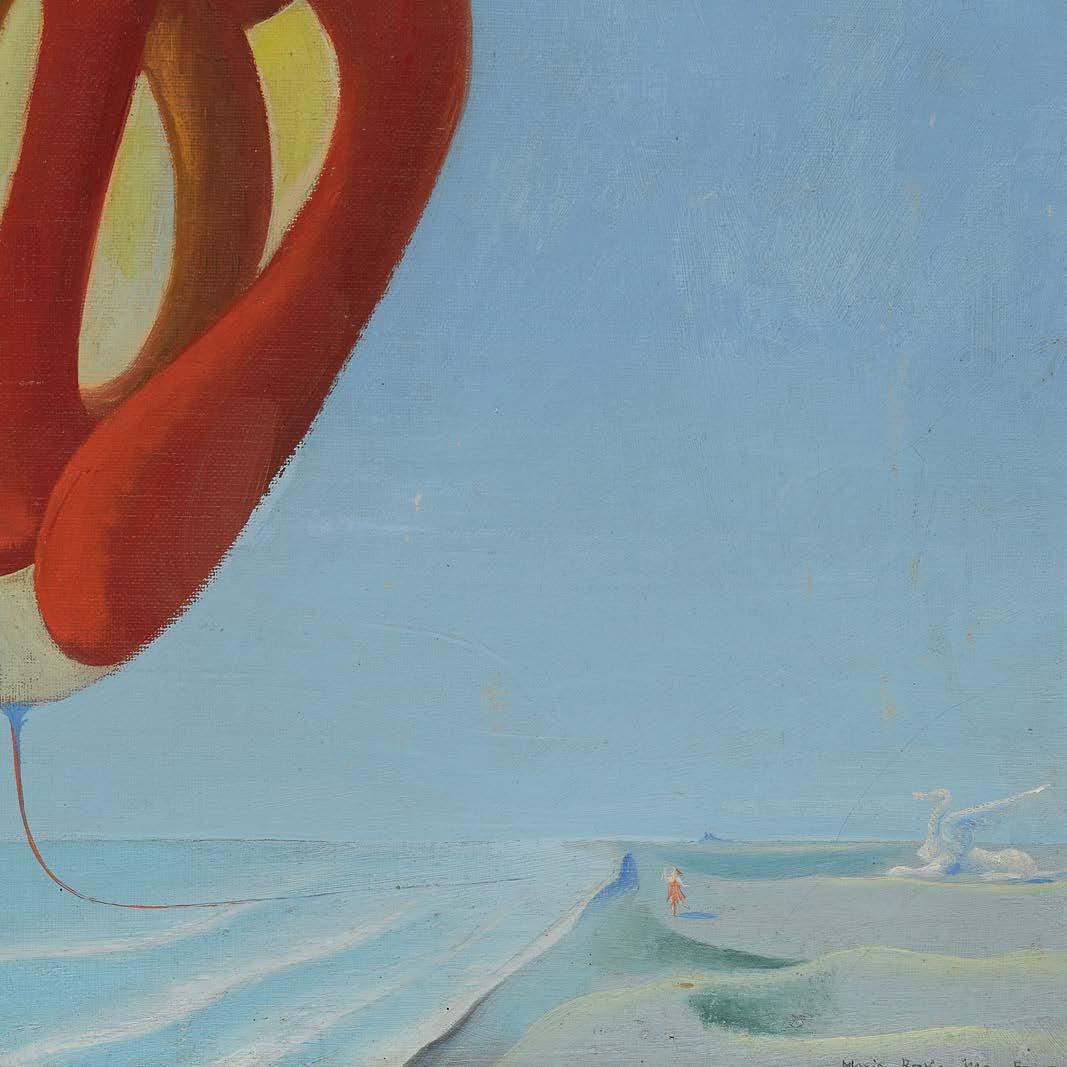

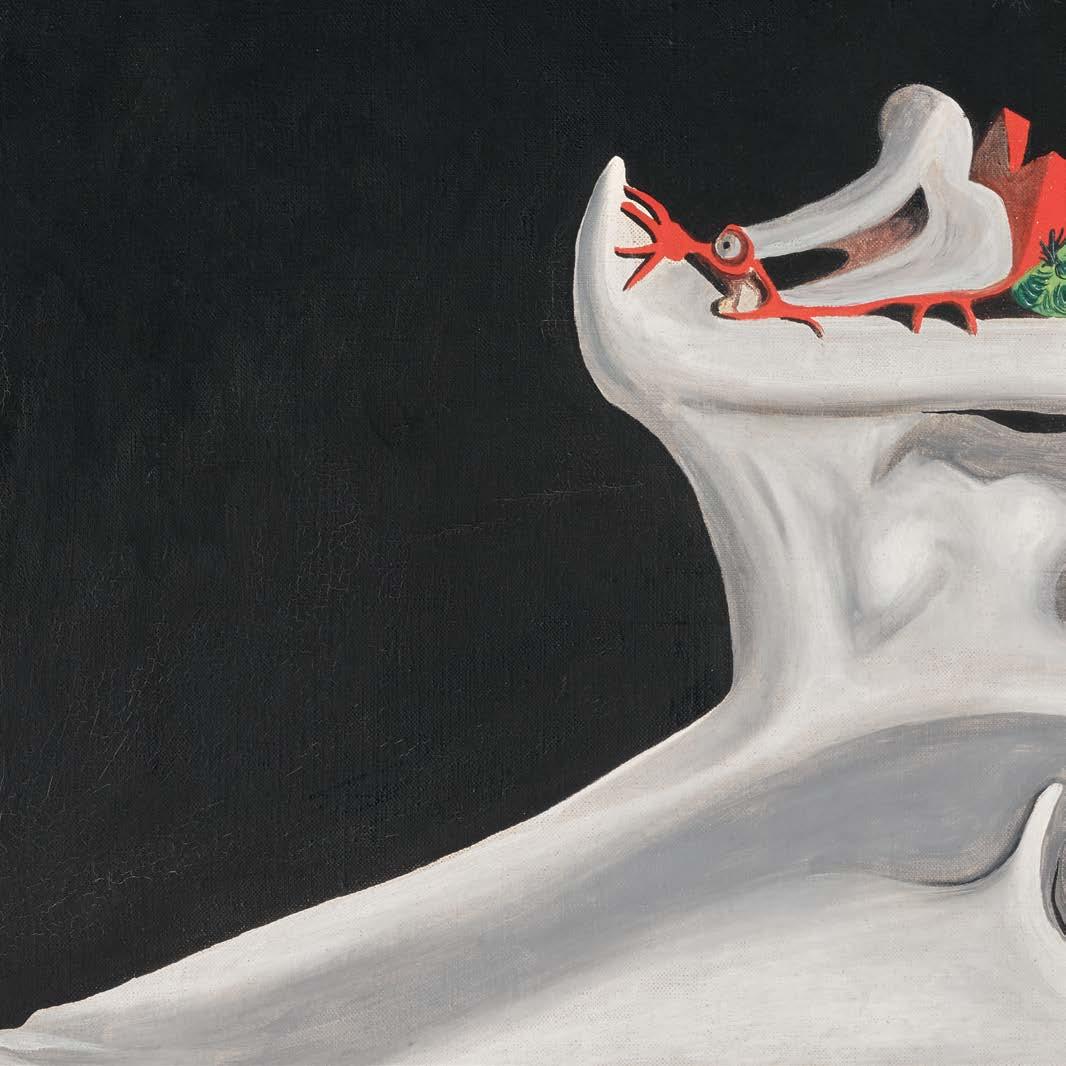

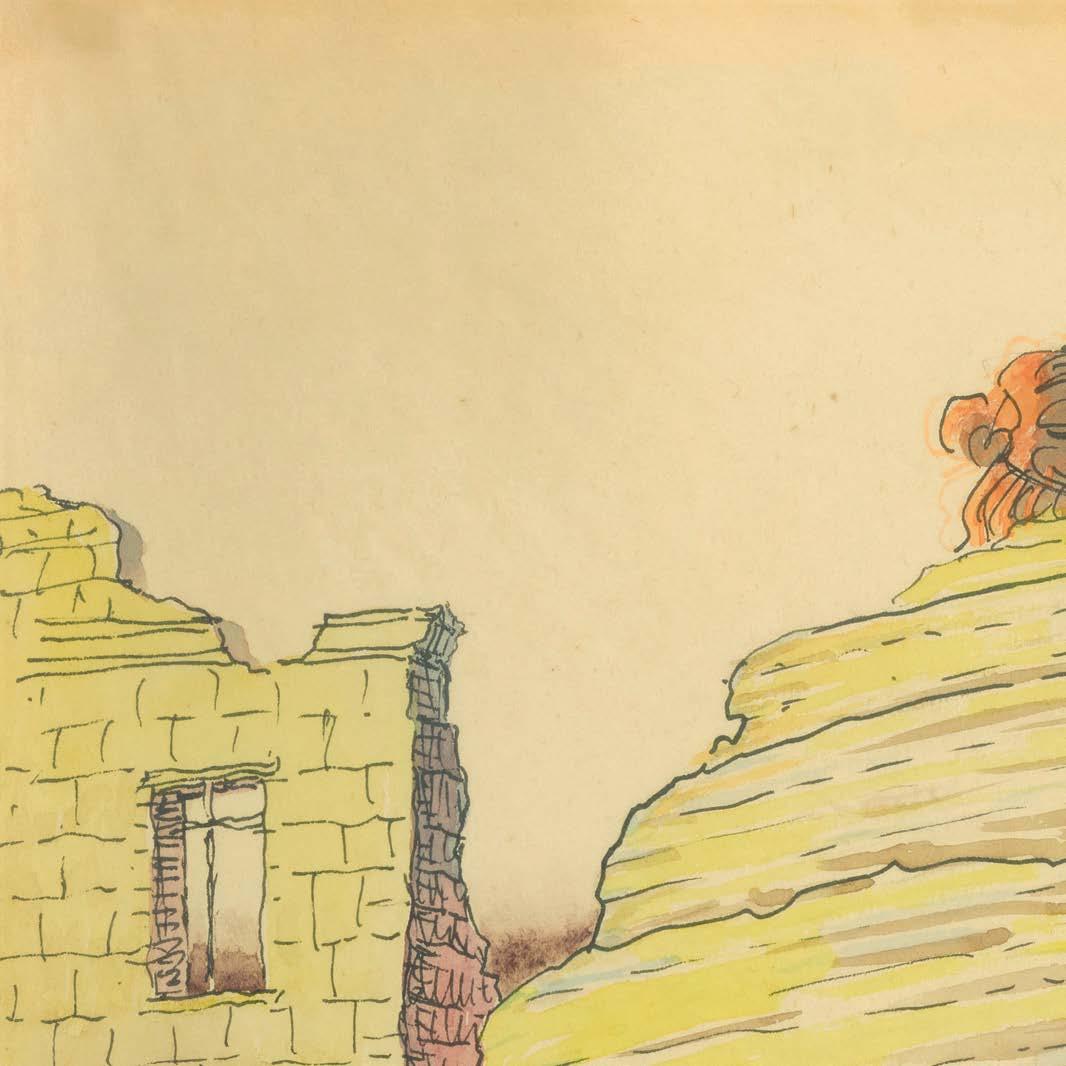

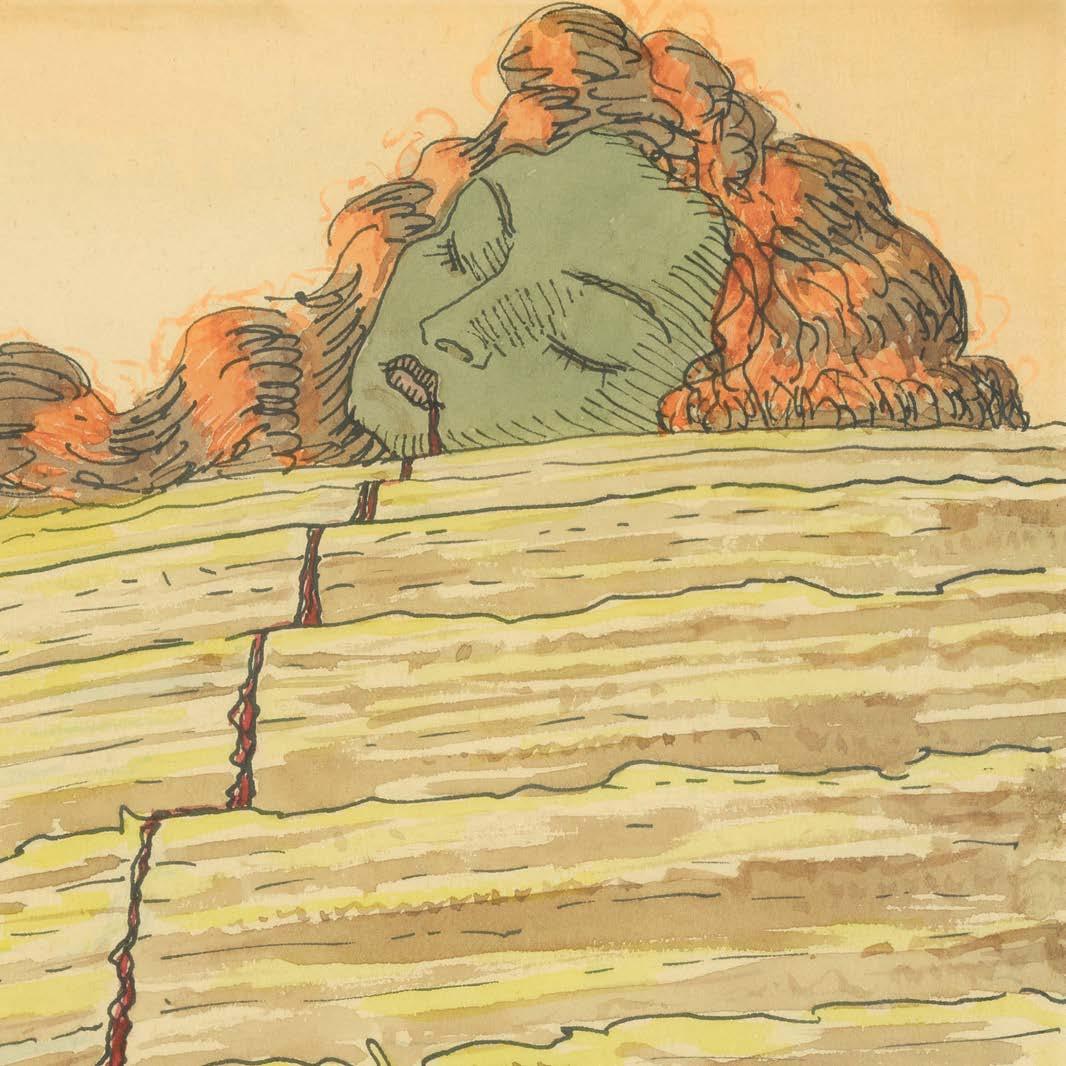

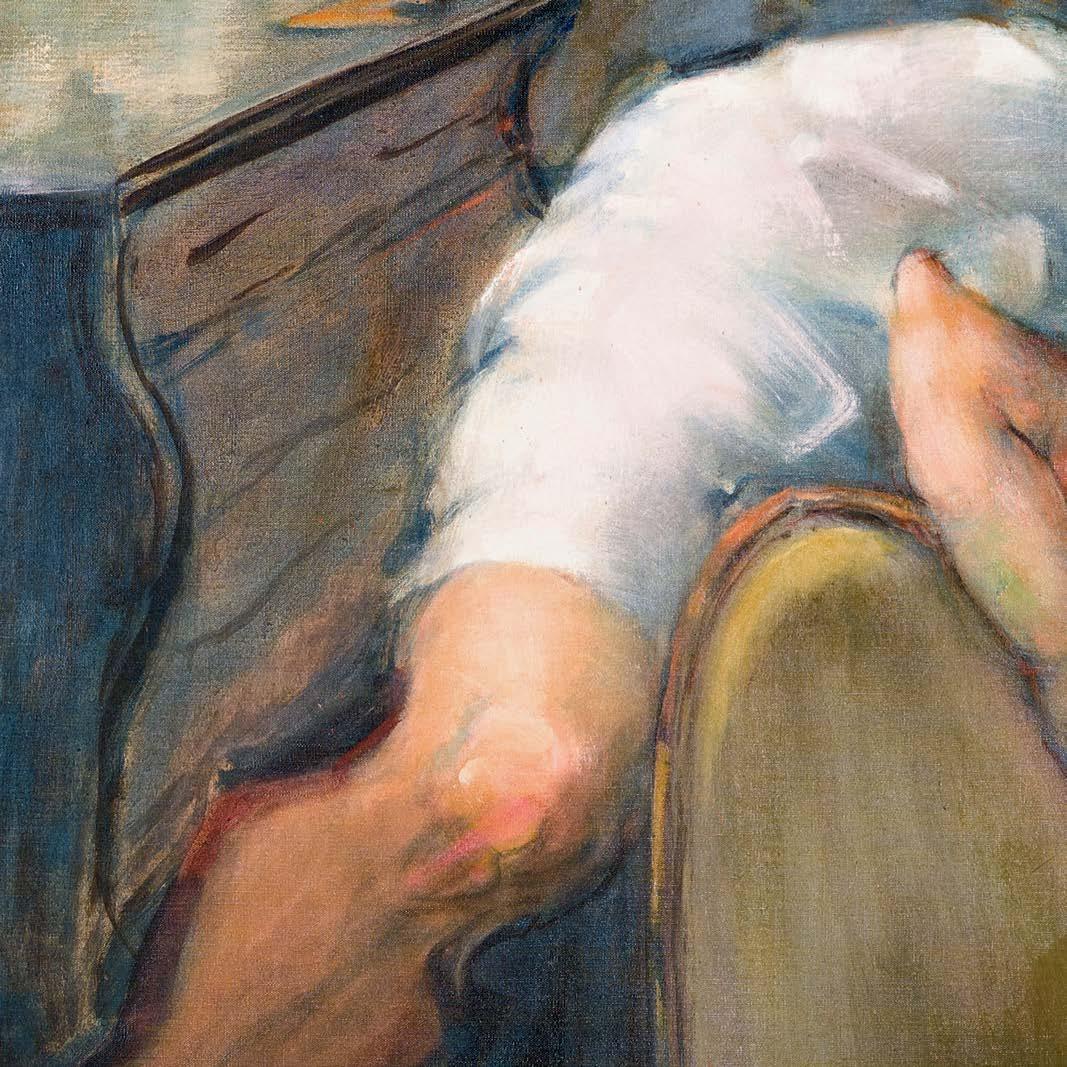

Salvador Dalí’s arrival in Surrealist circles in Paris in 1929 had an immediate impact; as Breton wrote, “It is perhaps with Dalí that all the great mental windows are opening.” The Spanish artist quickly became a figure of central importance, advancing the Surrealist cause not only through his enigmatic paintings but also through his critical writings, poetry, creation of Surrealist objects and gestes, and films produced with Luis Buñuel. Although influenced by Breton’s approach to Surrealism via automatism, Dalí’s principal contribution was the invention of ‘critical paranoia’—his term for the controlled use of freely associated imagery and subjects derived from selfinduced hallucinations. He developed a distinctive panoply of dream imagery reflecting a Freudian preoccupation with eroticism, death, and decay. These images—molten timepieces, outlandish animals, anthropomorphic objects, and eerie landscapes—were all rendered with scrupulous realism; Dalí delighted in the paradox of depicting the surreal and irrational through the visual language of verisimilitude.

Messager dans un paysage Palladien originally belonged to Edward James, a great patron and advocate of the Surrealist movement. Acquired directly from the artist, it resided for many years in James’ Surrealist-inspired home, Monkton, West Dean. In 1978, the work was featured in the documentary The Secret Life of Edward James, where it can be seen hanging on his bedroom wall at Monkton.

MESSAGER DANS UN PAYSAGE PALLADIEN

pen and ink on pink paper

50.2 by 63.2 cm. 19¾ by 24⅞ in.

Executed circa 1936.

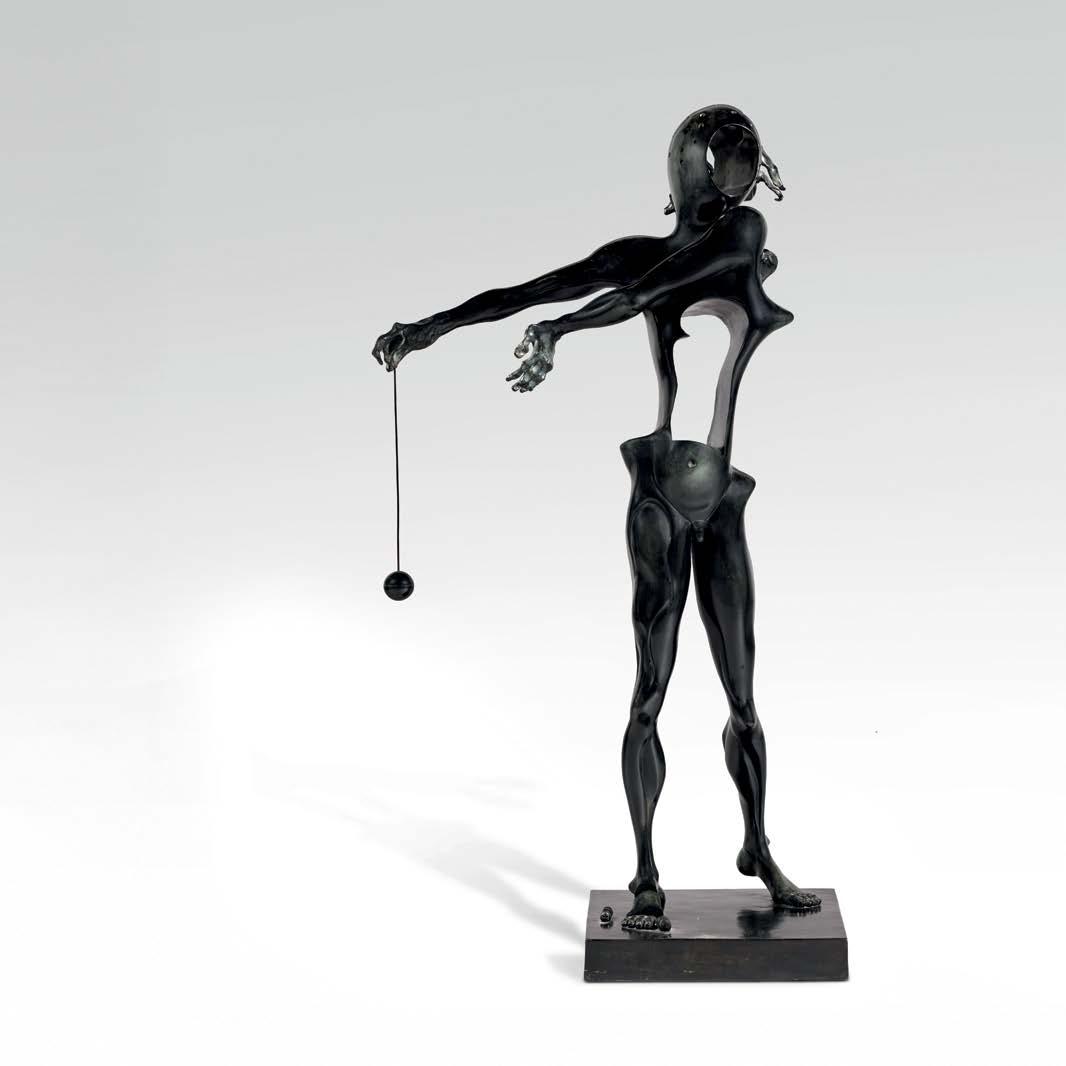

inscribed Dalí, numbered 1/8 and with the foundry mark C. Valsuani cire perdue bronze

height (including base): 131.5 cm. 51¾ in.

Conceived and cast in 1969 by the Valsuani Foundry, Paris. This work is number 1 from an edition of 8 plus 4 artist’s proofs and a further unnumbered cast outside this edition.

Formerly in the collection of André-François Petit.

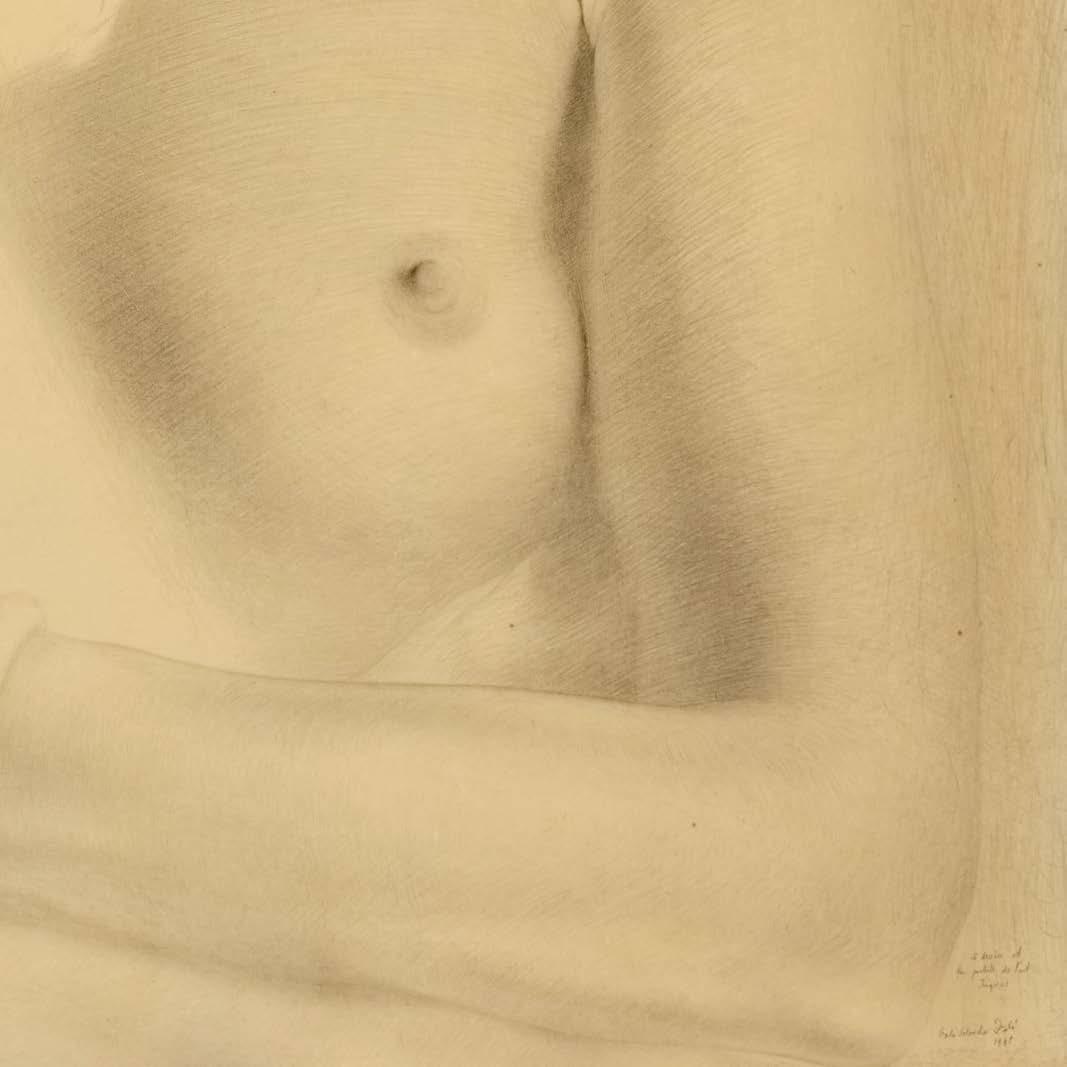

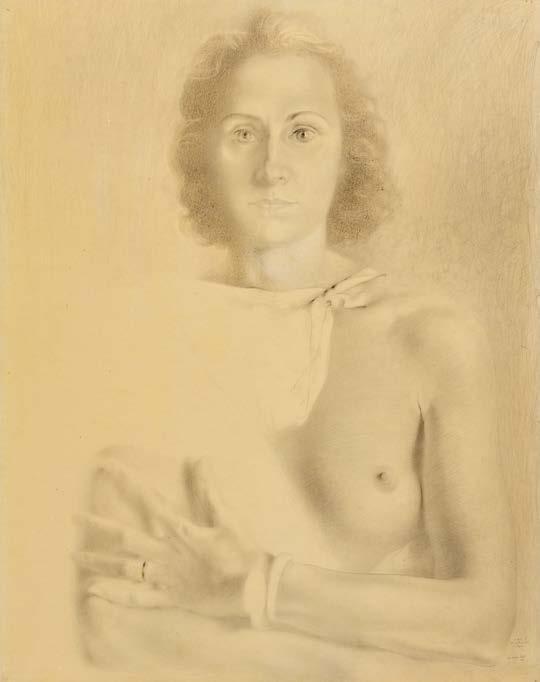

PORTRAIT DE GALA GALARINA

signed Gala Salvador Dalí, dated 1941 and inscribed Le dessin est la probité de l’art Ingres (lower right) pencil on paper

63.6 by 50 cm. 25 by 19⅝ in.

Executed in 1941.

Formerly in the collection of Edward James.

CANNIBALISME DES OBJETS, TÊTE DE FEMME AVEC

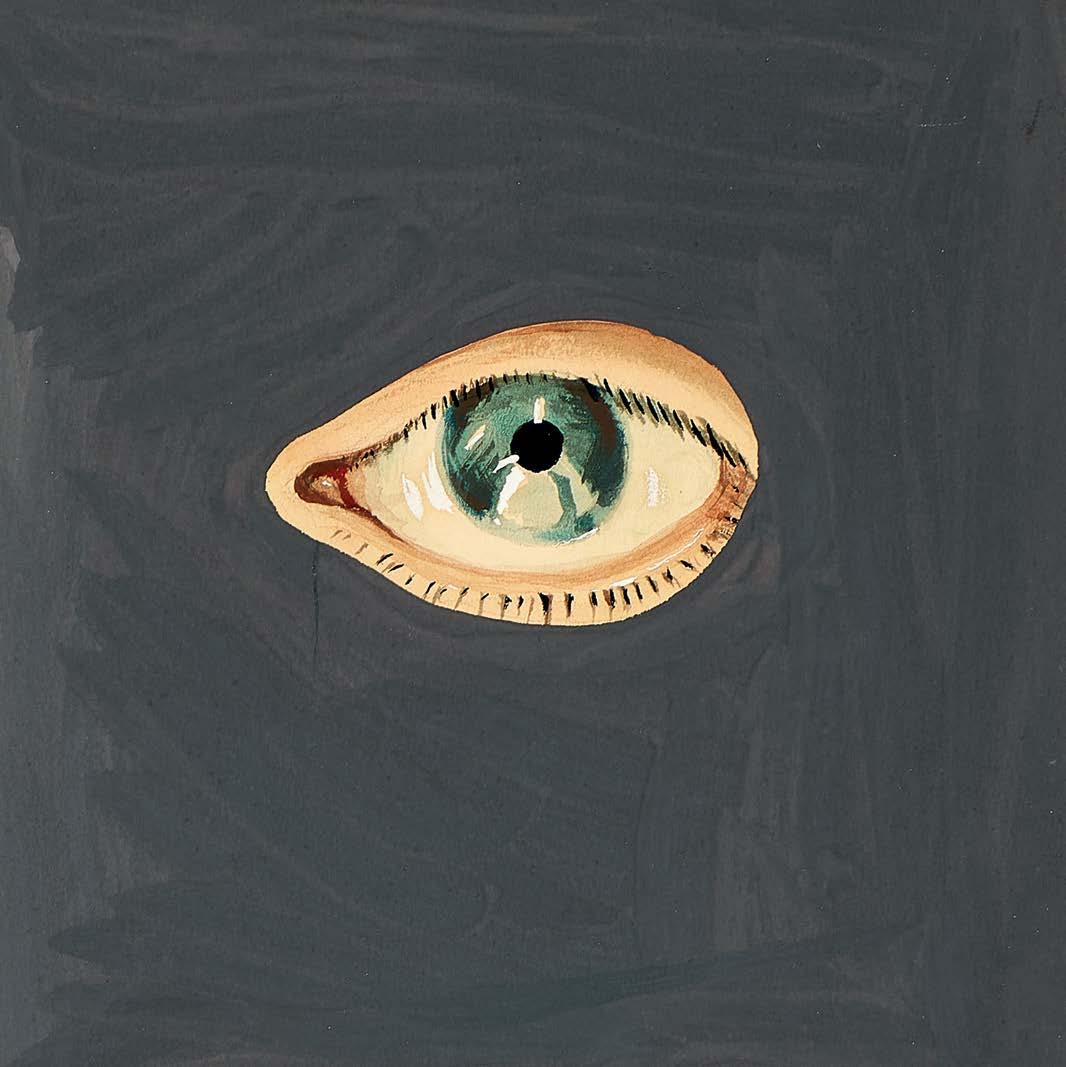

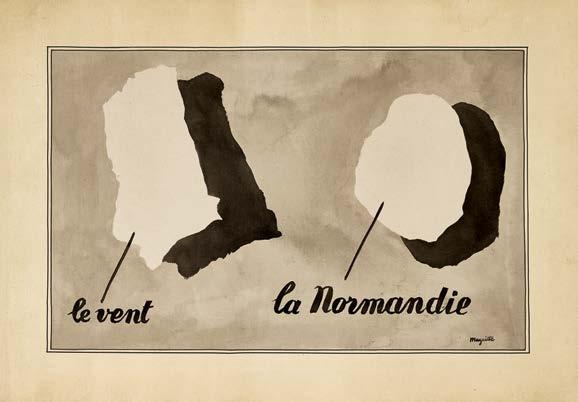

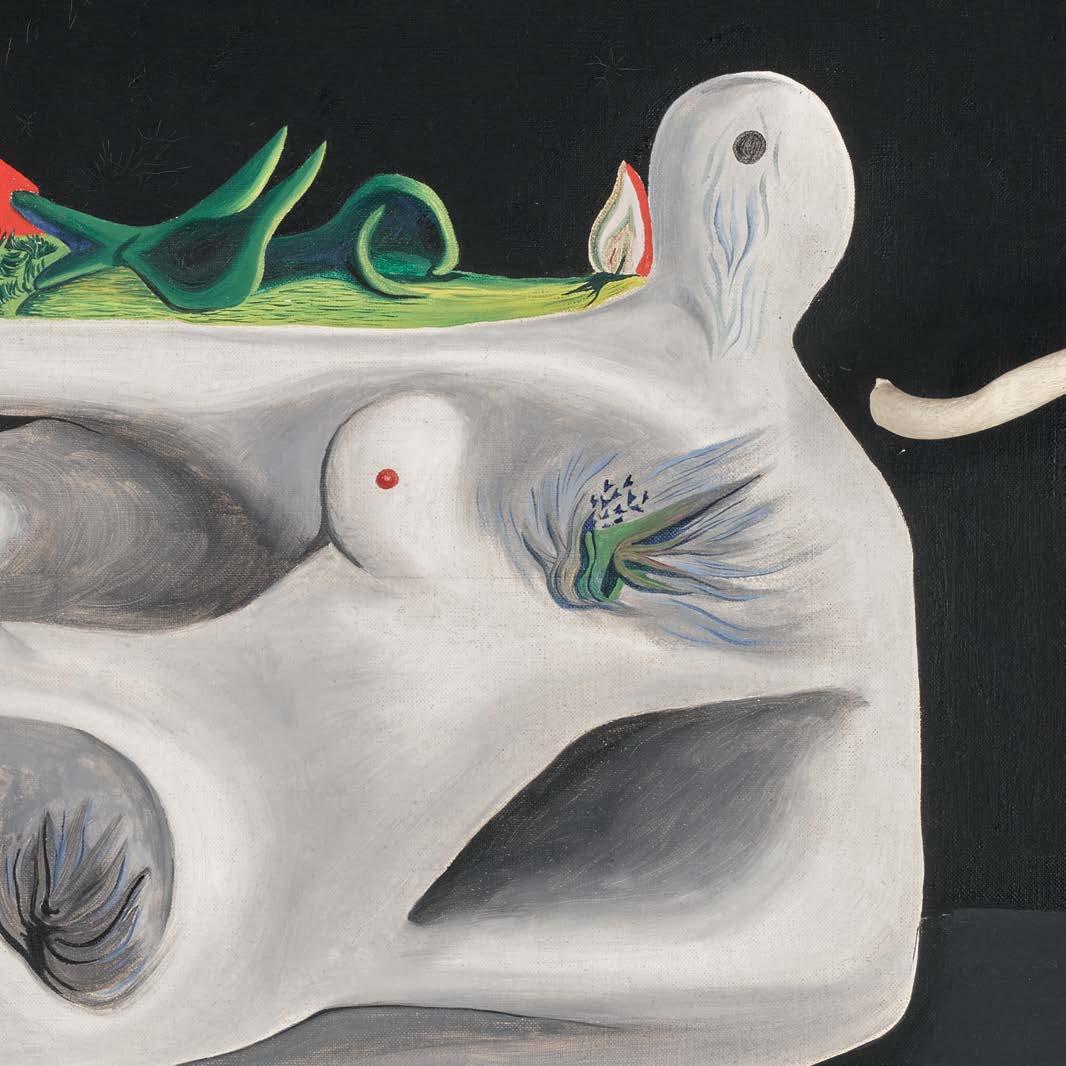

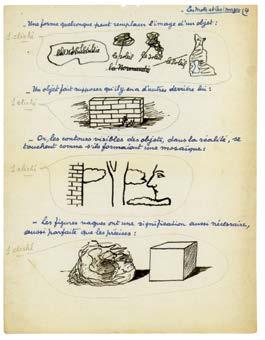

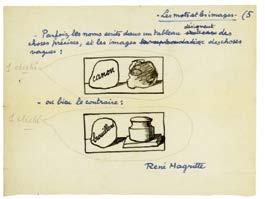

Like his contemporary Salvador Dalí, Magritte’s approach to Surrealism relied upon a precise, illusionistic technique to construct the irrational, often hallucinatory scenes characteristic of the movement’s desire to disconcert and disorientate. However, whereas other Surrealists sought to access the subconscious through automatic methods— such as frottage, decalcomania, or the depiction of expansive dreamscapes—Magritte generated a comparable atmosphere through the revelation of hidden affinities between everyday objects. His compositions often hinge on the juxtaposition of unlikely elements, inversions of scale, or the displacement of familiar items into unfamiliar contexts. Even his early peinture-poésie interrogates the nature of the object as part of a broader enquiry into linguistic and pictorial systems of representation.

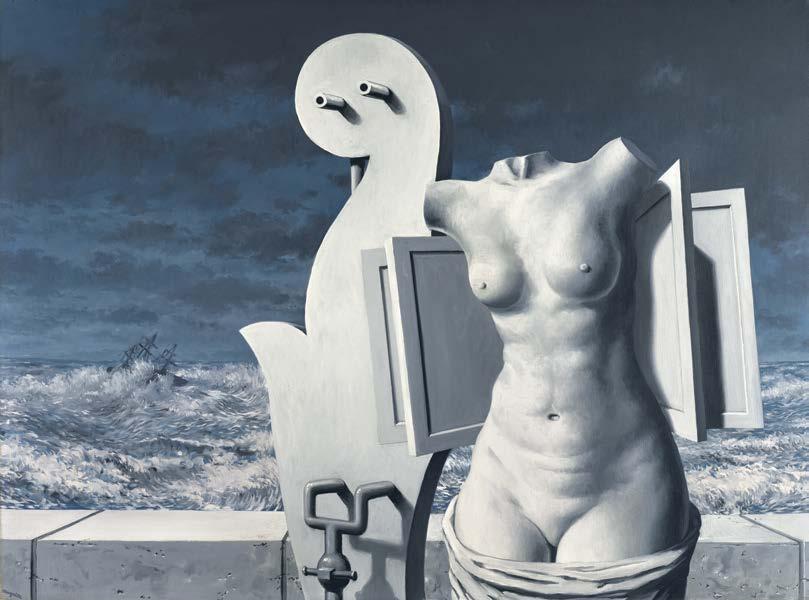

Magritte’s work challenges conventional modes of perception and the presumed stability of meaning, disrupting the transparency of representation and prompting viewers to question the relationships between image, object and language. Works such as La Statue volante and La Race blanche demonstrate Magritte’s capacity to invest seemingly classical and ordinary subjects with new and unsettling identities, encouraging a reappraisal of the logic of representation and the limits of visual certainty.

His meticulous, restrained technique heightens the sense of cognitive dissonance, reinforcing the enigmatic and elusive qualities of his compositions. In doing so, Magritte’s œuvre embodies Surrealism’s project to destabilise accepted ways of seeing and understanding the world—not through chaos or fantasy, but through a precise and poetic visual language that remains as conceptually provocative as it is formally refined. Magritte’s work has made a profound impact on the visual language employed by subsequent generations of artists, particularly within Pop and post-war art.

STATUE VOLANTE

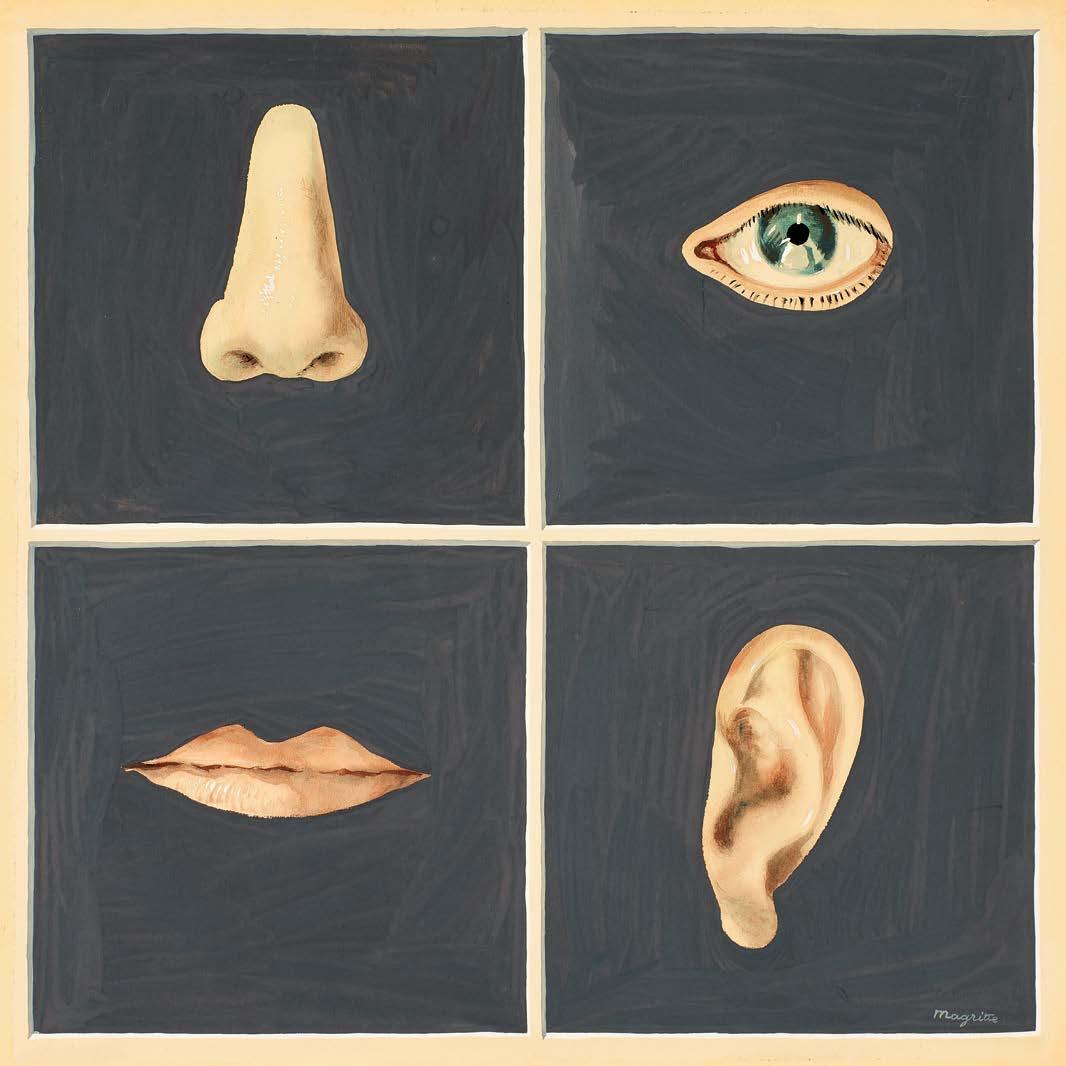

LA RACE BLANCHE

signed Magritte (lower right) gouache on paper

26.3 by 26.4 cm. 10½ by 10⅝ in.

Executed in 1937.

in the collections

painted plaster height: 32 cm. 12⅝ in.

Executed circa 1960. This example is 1 of 2 unique variants.

Formerly in the collection of Georgette Magritte.

LES MENOTTES DE CUIVRE

painted plaster height: 37 cm. 14⅝ in.

Executed in 1936. This work is unique.

Formerly in the collection of Charles Ratton.

SANS TITRE

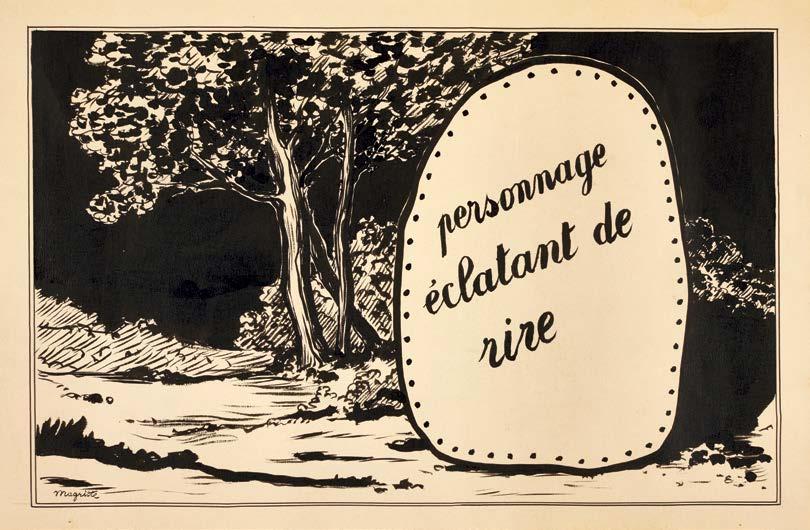

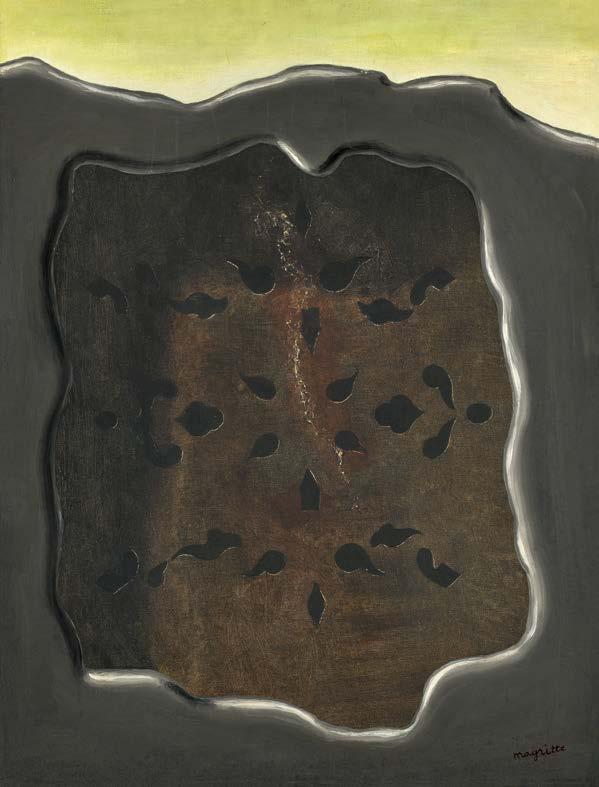

LE MONDE PERDU

signed Magritte (lower centre) brush and pen and ink on paper

32.6 by 46.3 cm. 12⅞ by 18¼ in.

Executed in 1928.

Formerly in the collection of E. L. T. Mesens.

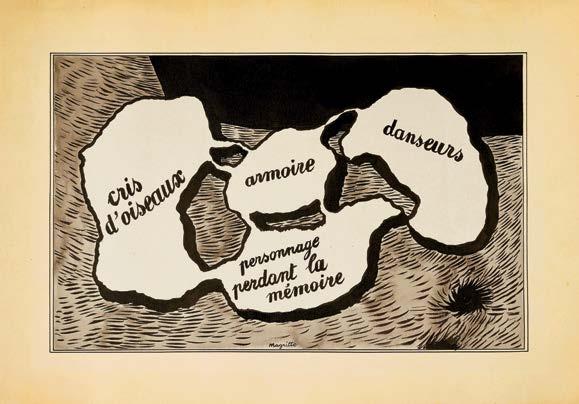

L’USAGE DE LA PAROLE

signed Magritte (lower right)

brush and pen and ink on paper

32.5 by 46.3 cm. 12¾ by 18¼ in.

Executed in 1928.

Formerly in the collection of E. L. T. Mesens.

LA RACE BLANCHE

inscribed Magritte and numbered 5/5 bronze height: 52.5 cm. 20⅝ in.

Conceived in 1967; this example cast by Fonderia Artistica Bonvicini, Verona in 1967. This work is number 5 from an edition of 5 plus 1 artist’s proof.

UNTITLED (LE SENS PROPRE)

74.8 by 55.8 cm. 29½ by 22 in.

Executed in 1927.

MADAME RÉCAMIER DE DAVID

inscribed Magritte, numbered 0/5, dated 1967 and with the foundry mark Fonderia Artistica, Gi. Bi. Esse Verona-Italy

bronze

lamp: 184 cm. 72½ in.

chair: 192 cm. 75⅝ in.

pedestal: 48.8 cm. 19¼ in.

Conceived in 1967; this example cast by Fonderia Artistica Bonvicini, Verona in 1967 in an edition of 8.

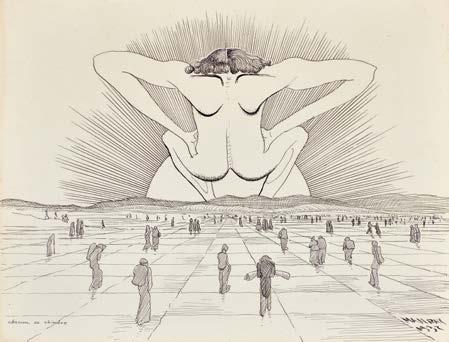

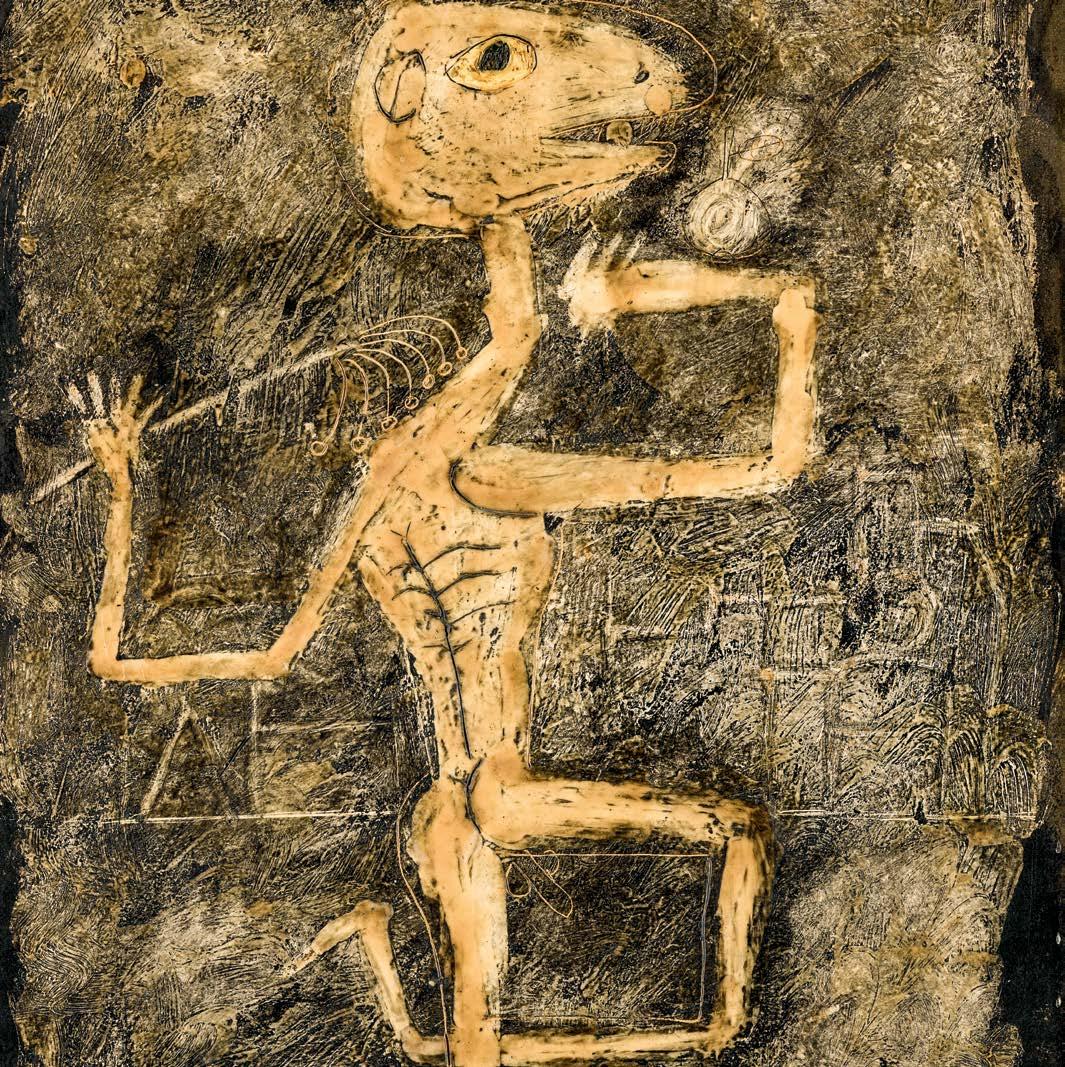

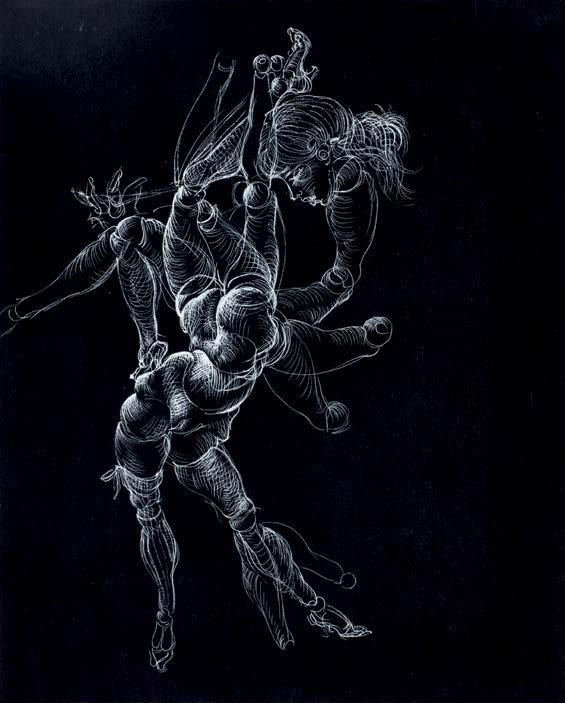

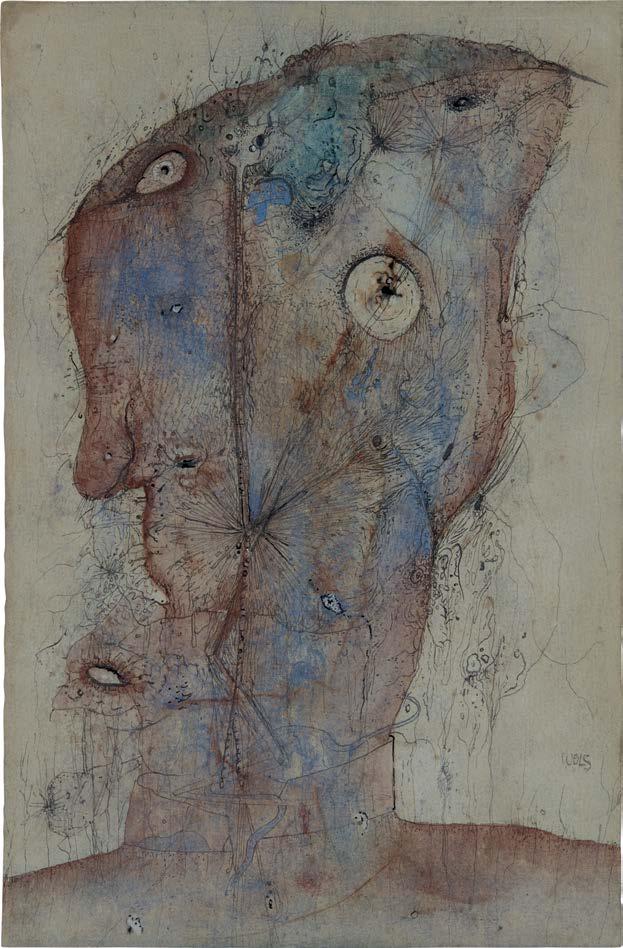

André Masson stands as one of the most significant early adherents of Surrealism, particularly through his experimentation with automatic drawing and spontaneous mark-making. Masson’s practice was deeply aligned with the Surrealist aim of accessing the unconscious and bypassing rational control.

Having studied at the Académie Royale des BeauxArts in Brussels and later based in Paris, Masson joined Breton’s circle in the early 1920s and became a leading practitioner of automatism, a technique that allowed him to visualise the unfiltered psyche through line and gesture. His automatic drawings— often dense, chaotic, and suggestive of both eroticism and violence—capture Surrealism’s fascination with the intersection of desire and destruction.

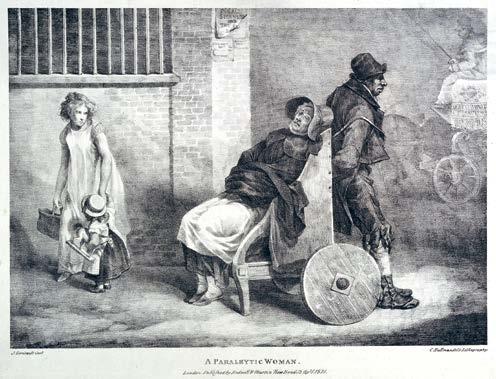

In the 1930s, Masson’s style grew more figural and mythological, exploring archetypal themes with visceral intensity, as seen in his 1939 painting La Femme paralytique. His engagement with the horrors of the Spanish Civil War expanded Surrealism’s political and psychological dimensions. After being declared a “degenerate” artist by the Nazis, Masson fled to the United States, where his improvisational approach had a formative influence on Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollock. His practice— spanning psychic automatism, classical mythology, and wartime trauma—exemplifies Surrealism’s evolving concern with the unconscious as a site of both poetic creation and psychic rupture.

CORRIDA MYTHOLOGIQUE

Executed in 1936.

Formerly in the collection of Fernande Schulmann-Métraux.

In the shifting shadows between dream and reality, Óscar Domínguez conjured visions that pulse with elemental force and uncanny beauty. Born in Tenerife in 1906, his early life amid volcanic landscapes profoundly shaped his artistic imagination. In 1934, he moved to Paris, where he quickly immersed himself in the vibrant avant-garde of Montmartre and joined André Breton’s Surrealist circle. Domínguez emerged as a vital figure within the movement, forging a practice defined by restless experimentation and psychological depth. His art traverses painting, sculpture, and objets surréalistes, harnessing automatism and symbolic imagery to explore desire, transformation, and the unconscious.

Throughout his career, Domínguez blurred boundaries —between the organic and mechanical, the sacred and profane, the seen and unseen—creating works that evoke both mystery and immediacy. His imagery, rich with biomorphic forms and metamorphic landscapes, channels the tension between improvisation and control, dream logic and sharp formalism.

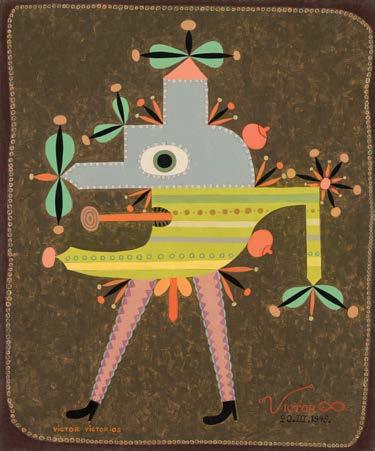

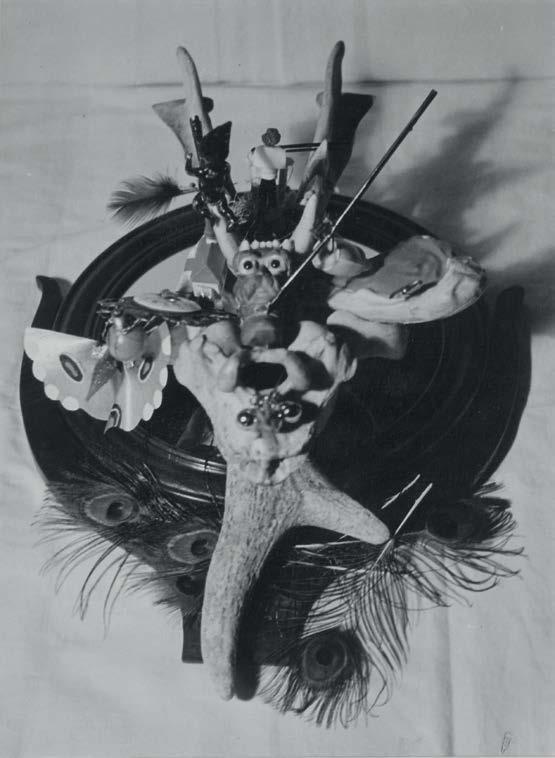

In this collection, works such as Le Piano (1934), which translates musical improvisation into a haunting fusion of sound and image, and Exacte sensibilité (1935), a striking hybrid of painting and sculptural assemblage, exemplify Domínguez’s unique ability to animate the surreal psyche through innovative form and texture. His work remains a powerful testament to Surrealism’s capacity to unlock hidden realms of imagination and emotion.

EXACTE SENSIBILITÉ

signed Oscar Dominguez and dated 1935 (lower right) oil on canvas with plaster, iron pipe, metal rod, spatula, plastic and sphere in the artist’s frame

54 by 90 cm. 21¼ by 35½ in. artist’s frame (with collage elements): 69 by 117 by 12 cm. 27⅛ by 46 by 4¾ in. Executed in 1935.

Formerly in the collection of Marcel Jean.

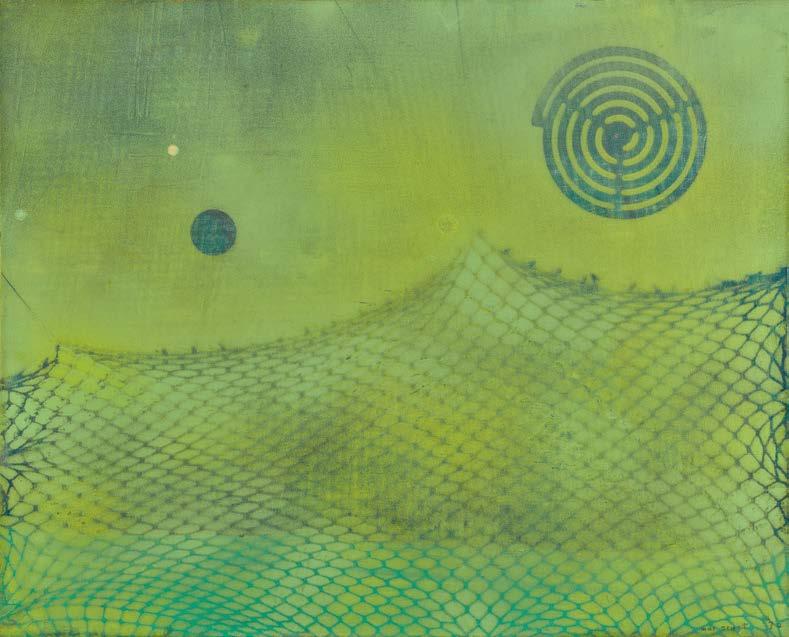

Yves Tanguy’s meticulously rendered dreamscapes are among the most enduring visual expressions of Surrealism’s preoccupation with the unconscious and the unknown. Inspired to become a painter after encountering Giorgio de Chirico’s work in a gallery window, Tanguy joined the Surrealist group in Paris in the mid-1920s and quickly developed a distinctive vocabulary of infinite horizons, muted skies, and enigmatic biomorphic forms. His technique— scrupulously detailed yet fantastically unreal—echoed the movement’s desire to visualise states of psychic dislocation and dreamlike logic.

Tanguy’s 1928 painting Titre inconnu exemplifies the movement’s interweaving of trauma, repression, and poetic ambiguity. His forms—strange, plasmic objects that seem to hover between matter and metaphor— embody the Surrealist fascination with liminality and transformation. After relocating to the United States during the Second World War with fellow artist Kay Sage, Tanguy continued to develop his practice in exile. His later works reflect a subtle shift towards American landscapes, yet remain tethered to Surrealism’s commitment to visualising the inner life through symbolic, ungraspable terrain.

TITRE INCONNU

signed YVES TANGUY. and dated 28 (lower right) oil on canvas

91.6 by 73 cm. 36 by 28¾ in. Executed in 1928.

Formerly in the collections of Raymond Queneau, Georges Hugnet, Simone Collinet and William N. Copley.

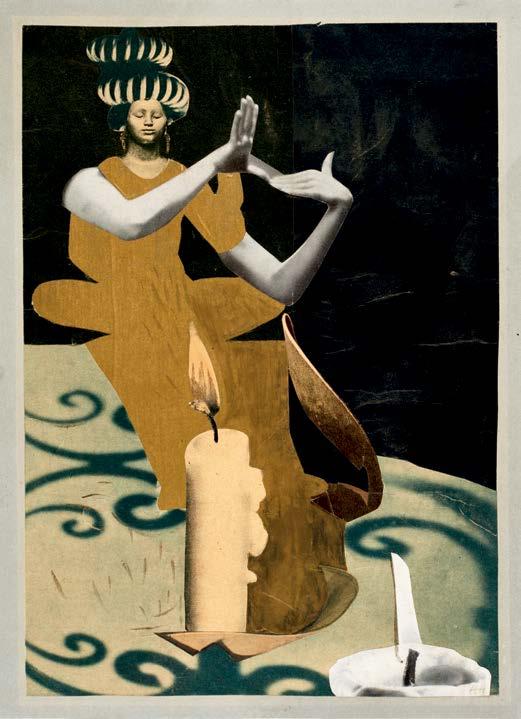

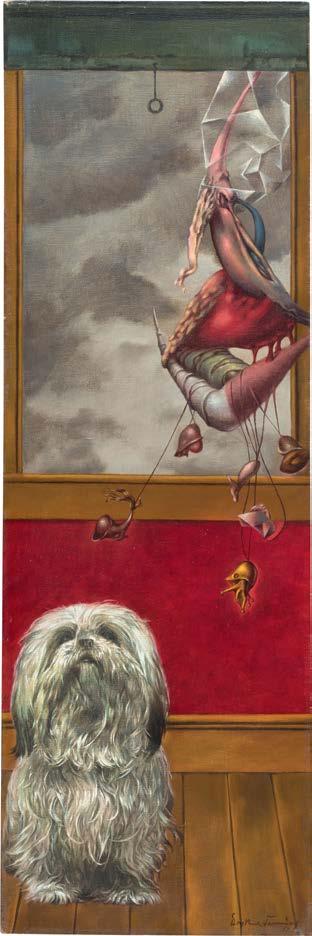

Leonora Carrington’s contribution to Surrealism lies in her singular ability to construct visionary worlds grounded in esoteric symbolism, myth, and the occult. Born to a wealthy English father and Irish mother, Carrington resisted convention from an early age, and her immersion in Surrealist circles in Paris in the late 1930s—through her relationship with Max Ernst and friendships with Breton, Dalí, and others— ushered in a body of work that combined narrative complexity with dream logic.

Her paintings, such as The Hour of the Angelus, are populated by chimeric creatures, alchemical symbols, and archetypal figures drawn from Celtic myth, Medieval alchemy, the Tarot, and Mesoamerican cosmology. These richly layered images often depict female protagonists negotiating identity and transformation in worlds where time is cyclical and boundaries between human and animal, waking and dreaming, are fluid. Challenging the canon of Surrealism, Carrington’s œuvre foregrounds the feminine experience and the mystical, expanding Surrealism’s reach into new mythopoetic realms.

HÖCH

BRETON, HUGO, KNUTSON & TZARA

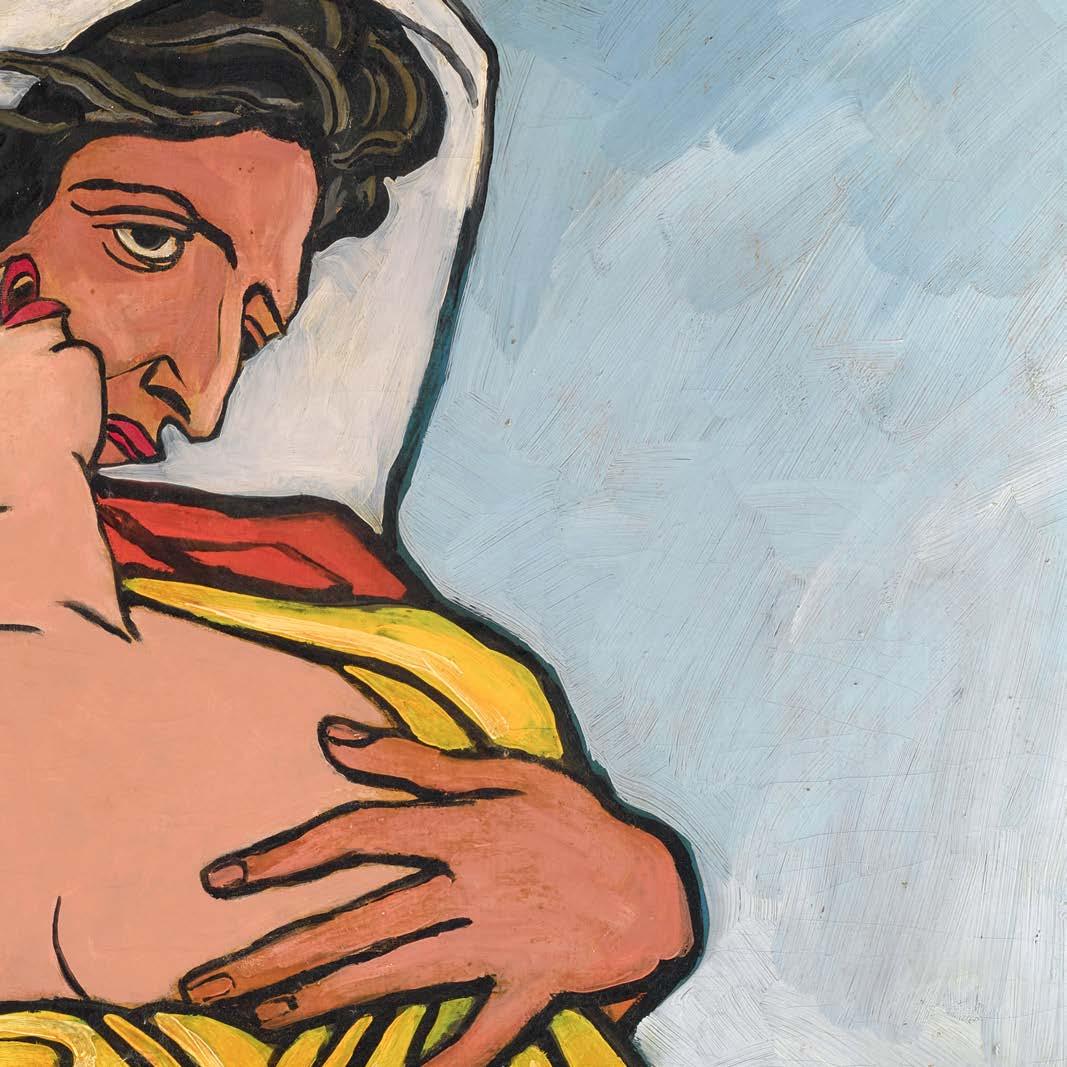

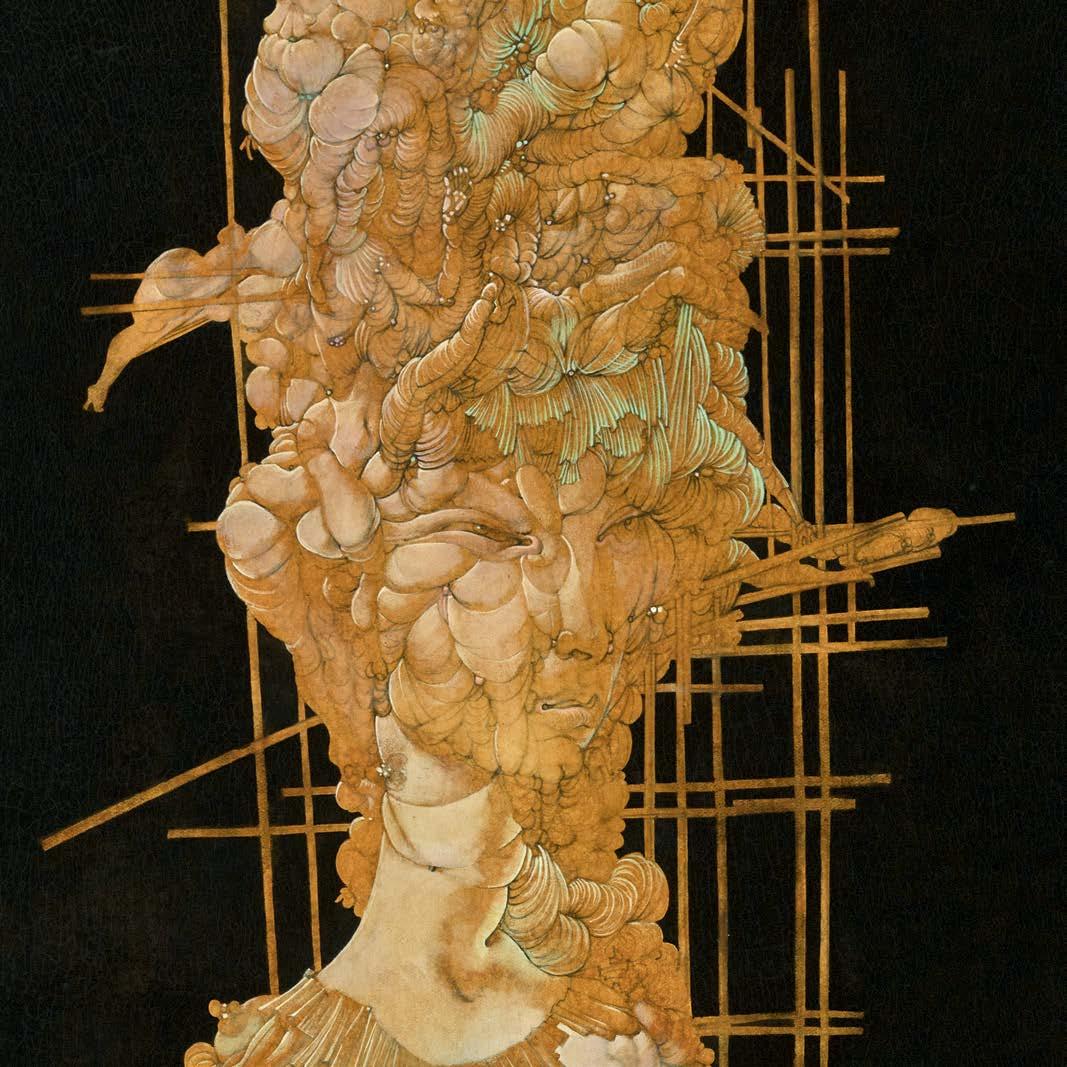

A mercurial and provocative figure, Francis Picabia occupied a vital, if often antagonistic, position within the early histories of both Dada and Surrealism. Initially rooted in Impressionism, he soon embraced Cubism before becoming a pivotal figure in the New York and Zurich Dada movements, where his mechanical drawings and iconoclastic imagery fundamentally challenged established aesthetic norms and anticipated Surrealism’s anti-rationalist tendencies. Although briefly associated with Breton’s Surrealist group in the 1920s, Picabia notably rejected the movement’s formal doctrines such as automatism, favouring instead layered and ambiguous “transparencies” that interrogated notions of figuration and abstraction alike.

During the 1940s, Picabia’s œuvre increasingly engaged with strategies of appropriation and the collision of high and low cultural signifiers, incorporating motifs from popular media, advertising, and mass culture alongside canonical art historical references. This deliberate hybridisation served as a critique of hierarchical cultural distinctions and prefigured postmodernist approaches to pastiche, irony, and the destabilisation of authorship. Paintings such as Deux amies exemplify this approach, presenting psychologically complex explorations of desire and identity through a fusion of popular imagery and painterly abstraction. Politically, Picabia’s work and stance must be understood within the context of fascist ascendancy and the suppression of avant-garde art by the Nazi regime. His artistic production during this period functions as a form of cultural resistance, challenging authoritarian ideologies through subversion, ambiguity, and the celebration of the irrational. His late-period paintings—characterised by eclecticism and vividness—continue to resist fixed interpretation, embodying a sustained interrogation of identity, meaning, and artistic freedom. Picabia’s legacy thus occupies a critical nexus between Surrealism and the emergent postmodern condition, marking him as both an innovator and a figure of political and artistic dissent.

HOMME ET FEMME AU BORD DE LA MER

UNTITLED (ESPAGNOLE)

signed Francis Picabia (lower right) oil and ink on board

104.3 by 75.1 cm. 41⅛ by 29⅝ in. Executed circa 1925-26.

Formerly in the collection of Renée Albouy-Moore.

BY DAWN ADES

Surrealism has had a complex, fascinating and paradoxical relationship with art and with the artists associated with the movement. To begin with, there is virtually no mention of the visual arts in the first Surrealist Manifesto (1924) by André Breton. This is surprising, given the background to its formation and the interests of its founders, who were themselves collectors. Secondly, despite the fact that Surrealism is probably best known internationally through its visual manifestations, it was never an art movement and cannot be identified through any particular style, unlike, say, Cubism or German Expressionism. It is different in kind from these “isms”. Why, then, have so many artists been drawn to and lived with it? What attracted them? Some were inherited from Dada— Max Ernst and Jean Arp, for example. Arp, whose miraculous Feuille se reposant is represented in the Karpidas collection, explained that “I exhibited along with the Surrealists because their rebellious attitude towards ‘art’ and their direct attitude towards life were as wise as Dada…’’1 For them, and for the many artists who followed, what seemed to pass as ‘art’ was worthless and had lost touch with lived experience. They were in revolt against modernism and sterile stylistic exercises. The appeal of Surrealism to artists lay outside any of the conventional paths through technique, style, subject, etc. It corresponded initially to a drastic sense of loss following the catastrophe of the First World War, after which it seemed as if the entire cultural and social landscape had been wiped out. As Breton put it, “…in the eyes of the artist the

exterior world had suddenly become empty… The model of yesterday, taken from the exterior world, no longer existed and could no longer exist. The model that was to succeed it, taken from the internal world, had not yet been discovered.”2 That discovery was to be made by Surrealism.

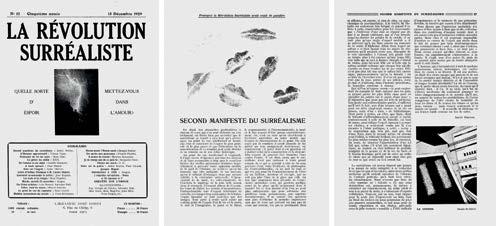

Surrealism was launched, in the autumn of 1924, with Breton’s Manifesto, a Bureau for Surrealist Research where people were invited to come in off the street to tell their dreams, and a journal, La Révolution Surrealiste, the first great Surrealist review, which ran from 1924 to 1929.

In the Manifesto of Surrealism, painting is mentioned only in a footnote; the primary concerns of the movement in formation are with language, poetry, life, and an unknown region to be explored, such as the unconscious. The Manifesto’s definition of Surrealism, while not excluding a visual dimension, is concerned with the nature of thought and how to express it:

“Surrealism. Pure psychic automatism, by which we intend to express, either verbally, or in writing, or in any other way, the real functioning of thought. The dictation of thought in the absence of any control exerted by reason, and outside any aesthetic or moral preoccupations.”

So, it is not just rational, conscious thought, but the whole internal world that lies beyond this, including what Freud called the subconscious or unconscious, which may reveal its workings in dreams.

1 Jean Arp, Collected French Writings London, 1973, p. 35

2 André Breton, “Genesis and Perspective of Surrealism”, in Peggy Guggenheim, ed., Art of this Century, New York, 1942, p. 17

“SURREALISM. PURE PSYCHIC AUTOMATISM, BY WHICH WE INTEND TO EXPRESS, EITHER VERBALLY, OR IN WRITING, OR IN ANY OTHER WAY, THE REAL FUNCTIONING OF THOUGHT. THE DICTATION OF THOUGHT IN THE ABSENCE OF ANY CONTROL EXERTED BY REASON, AND OUTSIDE ANY AESTHETIC OR MORAL PREOCCUPATIONS.”

EXTRACT FROM THE SURREALIST MANIFESTO FROM 1924

Unlike many manifestoes in the art world, the Surrealist Manifesto does not set out a programme or specific direction to follow, but proposes enquiry and exploration—Breton mentions as a precedent Columbus setting off for the New World, not knowing what he might find. The idea of automatism seemed to indicate a way forward. The Manifesto, in fact, started life as a Preface to Breton’s latest experiments in automatic writing, which were published with it as “Soluble Fish.” It wasn’t easy: the state of mind to write automatically, which demanded the suspension of conscious control of thought but enough consciousness to write sentences, was hard to attain. When achieved, the results were wonderful—texts full of startling poetic images.

The possibilities for artists, given there being no prescribed method or practice, were virtually endless. The first issues of La Révolution Surrealiste are dominated by photographs, film stills, objects, popular art, sketches by Giorgio de Chirico and Ernst, and the free pen-and-ink drawings by André Masson. The most convincing example of visual automatism, Masson’s drawings start as unconsciously as any careless doodle and flower into fragments evoking bodies, breasts, architecture, leaves and fruit. Other experiments in automatic processes were to include Ernst’s invention of frottage and decalcomania, as well as the vast field of the “optical unconscious” in photography, stunningly represented by Man Ray. Hence the fact that there is no single identity to visual Surrealism.

Automatism was necessarily, in the view of the Surrealists, present in the creation of the startling image, the unexpected juxtaposition of unrelated things.

It was an exhibition of collages by the Cologne Dadaist Max Ernst in Paris in 1921 which provided the spark that lit the Surrealist fuse. This was still at the height of Dada in Paris, whose participants were the future Surrealists, but already they were looking beyond dada negation. In his introduction to the catalogue for Ernst’s exhibition, which included extraordinary photocollages such as Nightingale, (acquired immediately by Paul Éluard), Breton recognised that photography and film had fundamentally changed conventional modes of expression, and articulated a concept of the image that was to become fundamental for Surrealism: the juxtaposition of two or more distant realities to create a new image. “…the marvellous ability to reach out, without leaving the field of our experience, to two distinct realities and bring them together to create a spark… Doesn’t such an ability make the person who possesses it better than a poet…?”3

Ernst—the poet-artist—had created the collages from a mixture of cut-up media—photographs, paint, wallpapers, whose juxtaposition created new images, unanticipatable associations and analogies. So the idea of the superior reality of images reached only in dream or some automatic process was there even before Surrealism was founded, and was embodied in the collages Ernst managed to send to Paris— though he was still stuck in post-war Germany. Ernst distinguished his collages/photo-montages, which he made in Cologne, from those of the Berlin Dadaists, such as Hannah Höch, whose work he regarded as too socio-political. Höch’s suggestive feminist photomontage Priesterin is in this collection.

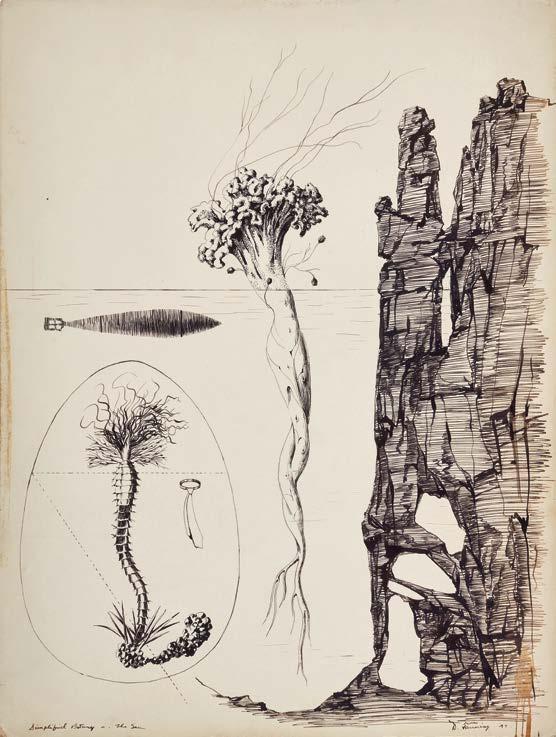

There are collages by Ernst from a slightly later period in the Karpidas collection which pursue a similar idea in a different way—this time working not with photography but looking back to nineteenth century engravings. Ernst made a number of collageengravings, his ingenuity never flagging, and created three collage-novels with them, perhaps the first graphic novels: La femme 100 têtes, 1929, Rêve d’une petite fille qui voulut entrer au Carmel, 1930, (translated by Dorothea Tanning, 1982) and Une semaine de Bonté, ou les sept éléments capitaux, 1934. The images in the novels have captions underlining their iconoclastic, erotic and witty character. The two collages here are the originals for two of the plates in Rêve d’une petite fille: the opening scene from the first chapter, with the caption “Le Père: “ Votre baiser me semble adulte, mon enfant. Venu de Dieu, il ira loin. Allez, ma fille, allez en avant et…” (‘The Father: “Your kiss seems adult, my child, Coming from God, it will go far. Go, my daughter, go ahead and…”’), and another plate from the same chapter, “…jusqu’à épuisement complet des beaux danseurs!” (…until the beautiful dancers are completely exhausted). The two collages came from the collection of Julien Levy, the New York dealer, who put on ground-breaking shows of Surrealist artists in the 1930s, when they were virtually unknown outside France. They may well have been among the collages he showed in Ernst’s first solo show in the United States, Exhibition Surrealiste MAX ERNST, in November 1932.

Collections of Surrealism are a very interesting way of approaching the rich and varied work of the many artists who have aligned themselves at some point with the movement. Collections made by the Surrealists themselves and collections of Surrealism are not quite the same. The Surrealists—most notably Breton himself, his wife Simone and the poet Paul Éluard—collected the works of their friends and colleagues, wrote about them and organised exhibitions to display them. These activities were part of the lifeblood of the movement and their choices played an important role in the long evolution of visual Surrealism. What this could be, as we shall see, was much disputed.

Breton, Simone and Éluard shared the hunting instinct of the true collector. Among Breton’s earliest

purchases, probably in 1922, was de Chirico’s The Child’s Brain, 1914, a key painting from de Chirico’s metaphysical period (1912-18), which he kept until 1964, two years before his death. He had glimpsed the painting, from a bus, in the window of Paul Guillaume’s Gallery and been transfixed. De Chirico was to be a central but controversial figure in the development of Surrealist painting.

Breton was also a passionate supporter of Picasso, and several Picassos passed through his hands. He had reluctantly taken a post in the early 1920s advising the couturier and collector Jacques Doucet, and managed to persuade Doucet to buy, and Picasso to sell, the Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, now in MoMA, which had remained rolled up in Picasso’s studio, for 25,000 francs.

The works he and Simone bought were never regarded as trophies, but objects with special kinds of power and expressive communication. Breton scrutinised the compulsion to possess behind his own collecting and speculated that it was not just ownership, having the painting or object in one’s power: caresser du regard ou les changer d’angle, being able to look at it, handle, move it about, but the hope of seizing its power for himself: “l’espoir de m’approprier certains pouvoirs qu’électivement à mes yeux ils détiennent.”4

Obliged frequently to sell, Breton wrote movingly of this painful necessity:

“As, over the course of my life, I have been far from being able to keep all these paintings that I had managed to bring into my home, I distinguish quite well from those which it was not too cruel for me to part with, those that I have never ceased to regret, even that I find it difficult to forgive myself for having had to give up to another fate than mine. I limit myself to mentioning, among the latter, Mystery and Melancholy of a Street, by de Chirico, Woman with a Mandolin, by Picasso, and above all The Bride by Duchamp.”5

Paul Éluard, by contrast, had deeper resources and amassed large collections. Both he and Breton bought not only work by their contemporaries but non-Western art, a strong feature in the Surrealists’ collections. In 1931 the “Collection André Breton and Paul Éluard” of African, American and Oceanian sculpture, with over 300 pieces, was exhibited at the Ratton Gallery, then sold at the Hôtel Drouot. Both continued to collect in this field, notably North West Coast First Nations art.

While like all collectors, Éluard bought and sold occasionally, two of his Surrealist collections were sold en bloc. The first, at the Hôtel Drouot in Paris in 1924, on the eve of his dramatic departure to the Far East to start a new life (he was eventually persuaded home by his wife Gala and Max Ernst), had included Ernst’s Le Rossignol Chinois, eight de Chiricos and five Picassos. The second was a private sale to his friend Roland Penrose in 1938. Penrose bought Éluard’s entire collection for £1,600, as stipulated by Éluard; it contained “six de Chirico’s, ten Picasso’s, forty Ernst’s, eight Miró’s, three Tanguy’s, four Magritte’s, three Man Ray’s, three Dalí’s, three Arp’s, one Klee, one Chagall and various other paintings and objects.”6

A number of works in the present sale have passed through these or other significant Surrealist collections. Among the “other paintings” in Éluard’s collection, for example, was Le Piano, 1934 by Oscar Dominguez, a prominent figure among the Surrealist group in Paris in the 1930s. Tanguy’s Titre Inconnu, 1928, and Masson’s La Femme paralytique, 1939, were in the collection of Simone Collinet, as she became after her divorce from Breton.

4 André Breton, “C’est à vous de parler, jeune voyant des choses…”, in revue XXe siècle: Art et Poésie depuis Apollinaire, 1952 and Perspective Cavalière, 1970, Paris, p. 17

5 André Breton, “À l’œil nu”, in revue XXe siècle: Art et Poésie depuis Apollinaire 1952, n.p.

6 Jean-Charles Gateau, Paul Éluard et la peinture Surrealiste (1910-1939), Geneva, 1982, p. 359

7 The exhibition travelled to Rotterdam and Hamburg.

Collections of Surrealism assemble works according to the tastes and interests of the collector, sometimes emphasising one or other aspect of the movement, or focussing on the work of a particular group or artist. Lindy and Edwin Bergman built up an unrivalled collection of Cornells, for example, while their fellow Chicago collector Joseph Shapiro was drawn to Roberto Matta. There are often different connections, placing works in new contexts, and each collection has its own character. Four of the greatest were featured in the exhibition Surreal Encounters: Collecting the Marvellous. Works from the Collections of Roland Penrose, Edward James, Gabrielle Keiller, Ella und Heiner Pietzsch (Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh 2016).7 Of these only Roland Penrose was a member of the Surrealist movement.

I have always thought of Pauline Karpidas’s collection in the context of Surrealism. It contains a wide range of works by Surrealist artists, many with provenances from Surrealist collections. I first met Pauline through my research on Dalí, and benefited from her generosity with loans, for example Dalí’s 1936 painting Le Sommeil (formerly in the Karpidas collection).