10 minute read

SPECIAL FEATURE

Fracking It turns out that the Central Coast sits atop the mother of all shale oil fields. BY TOM FRANCISKOVICH What does that mean for our future?

first heard that funny sounding word,

I“fracking,” a couple of years ago and, aside from a very rudimentary understanding, I really did not know much about it until recently. And, the more I dug into the issue the more I realized how important it is because, as it turns out, there is much more to the Central Coast than its beautiful coastlines and scenic landscapes. Deep beneath its golden, vineyard-filled rolling hills and its distinctive oak-pocked volcanic plugs rests the country’s largest domestic shale oil field: The Monterey Shale. Currently, multinational oil companies are lining up for a piece of the action in anticipation of one of the largest economic booms of all time, bringing jobs and wealth and tax revenue to our area unlike anything we have ever seen. And the whole thing got me thinking…

When President George W. Bush boldly declared in his 2006 State of the Union address that, “America is addicted to oil,” the news came as a surprise to no one. Bush was just one in a long line of presidents who recognized the unsustainable path of our country’s energy demands. But unlike President Jimmy Carter, who installed solar panels on the White House and admonished Americans to turn down their thermostats while addressing them in a cardigan sweater during the depth of winter, Bush, instead of trying to reduce demand, found a way to increase supply.

The technique for oil and natural gas extraction, known as hydraulic fracturing—“fracking” for short—was first developed in 1947. But, it was expensive and cumbersome and not all that effective. Plus we had a willing trading partner in OPEC and oil was cheap and there was plenty of it. The nascent fracking technology sat in oil executives’ file cabinets for years in favor of the low-hanging fruit, such as off-shore wells and small-scale drilling on private property.

But, mostly, the guys in the Middle East kept selling us the stuff and we kept driving our kids to soccer practice in 6,000 pound SUV’s, and life was good. While policymakers and presidents had been wringing their hands over the precariousness of our situation, the

American public had long forgotten about the gas rationing of 1973 that came as a result of

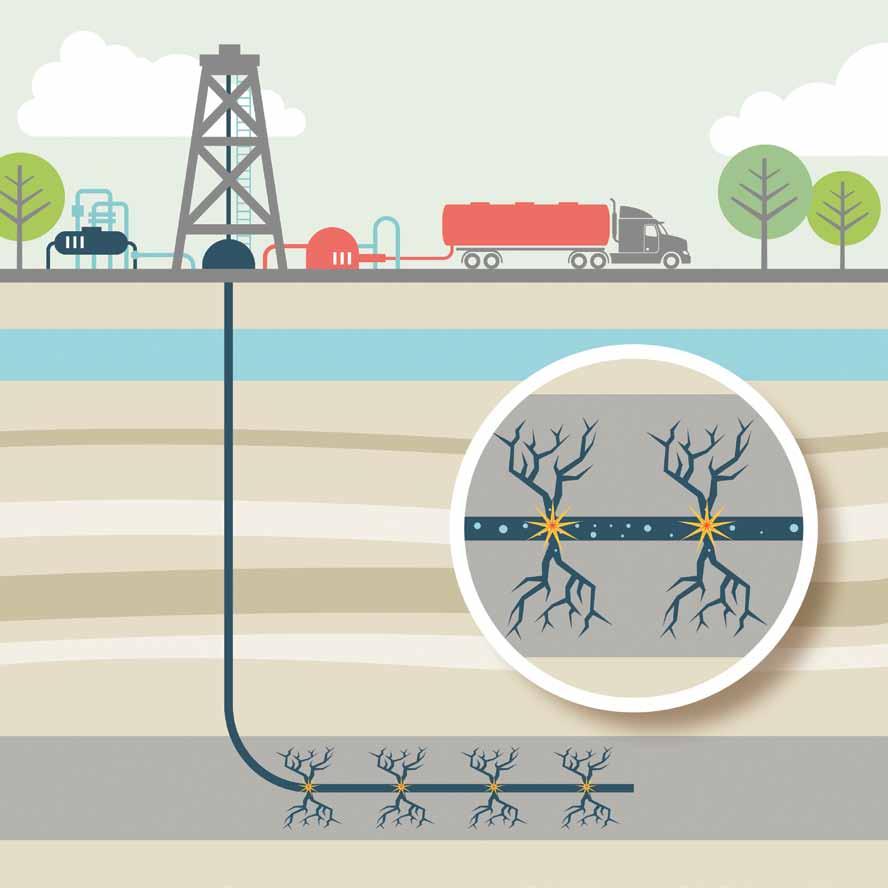

OPEC’s oil embargo. 2006, oil prices had been holding relatively steady at around $65 per barrel, but his declaration of dependence marked the beginning of its ascent to a peak of $147.50 during the summer of 2008 (it is around $105 per barrel currently). Skyrocketing prices combined with mounting evidence that the Saudis were funding Al Qaeda made domestic exploration a top priority. The exuberant chants of “Drill, Baby, Drill!” could be heard from the 2008 Republican National Convention on the floor of the Xcel Energy Center in Saint Paul, Minnesota and captured the hearts and minds of many Americans. Politician after politician made the case that our national security was at stake and we now had the ability to get the black gold that lay just below our feet. Although, curiously, no one used that word—fracking. The concept is rather simple. Hydraulic fracturing requires drilling a hole far down into a bed of shale rock to liberate what is called “tight oil” in the industry (the same technique can also be used to extract natural gas). The well goes straight down below the drinking water supply where it makes a sharp 90 degree turn and runs horizontally into the thick layer of shale. A mixture of water, sand, and chemicals called the “fracking fluid” are then blasted into the rock at approximately 4,200 gallons per second effectively creating tiny fissures in the shale (less than 1mm thick). The sand finds its way into the cracks to hold them open allowing the oil to seep out. It is then pumped up to the top and put into a truck for a trip to the refinery. So what’s the problem? For starters, it takes 3 to 8 million gallons of water for the average well to extract its oil. But, with oil at over $100 per barrel the math is easy: buy the water for a penny and sell the oil for a dollar. The real problem, aside from the massive amounts of wasted water, are the chemicals found in the fracking fluid—there are approximately 40,000 gallons of unnamed and unknown chemicals used per fracking site. And those chemicals, as it turns out, are considered proprietary and are protected by the Trade Secrets Act, the same law that allows Colonel Sanders to keep us in the dark about his chicken recipe. The Colonel does tell us that he uses “11 herbs and spices” however, which is much more than we know about fracking fluid. Despite the fact that the oil executives have been chicken when it comes to sharing their original recipes, it has been found that, historically, the

Franck Mecham (805) 781-4491 fmecham@co.slo.ca.us

Bruce Gibson (805) 781-4338 bgibson@co.slo.ca.us Adam Hill (805) 781-4336 ahill@co.slo.ca.us

Debbie Arnold (805) 781-4339 darnold@co.slo.ca.us

most common chemical used in fracking is methanol. And, this is where things get really interesting. Methanol becomes methane during the fracking process. Methane is the leading cause of global warming, the worst of the greenhouse gases that climate change deniers refer to dismissively as “cow farts.”

Interestingly, the San Joaquin Valley, where cow farts are commonplace, has seen a rise in fracking opposition coming from an unlikely coalition of farmers and environmentalists who view a dwindling water supply as the common rallying point. Opponents also point out that, in addition to the water that is diverted from crops and the toxic chemicals that pollute the ground, methane gas is also naturally abundant in shale rock. So, with each barrel of oil we pump out of the ground we are also liberating some unknown numbers of cubic tons of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. It may not be exactly like Tom’s Shoes “One for One,” but it is some ratio that is sending us further toward a point of no return. Incidentally, it is the methane gases that are trapped in northern tundras that worry climate scientists the most: as the weather warms, the ice melts releasing more methane into the atmosphere, which further accelerates the process. Additionally, methane gas has made its way into the drinking water supplies of communities near fracking operations, as stories of water coming out of the tap and catching on fire are commonplace. According to one independent study, methane concentrations were found to be 17 times higher in drinking water wells near fracking sites.

All of this brings us back to our home here on the Central Coast, a special part of our Creator’s Kingdom or a pure accident of geology, depending on your own belief system. Regardless of how it came to be, the same landscape that you and I and thousands of visitors cherish is now being viewed by oil executives with dollar signs in their eyes. Because below our feet sits the mother lode of all shale formations, the 1,750 square miles known as The Monterey Shale, which the US Government estimates to contain 15.4 billion barrels of recoverable oil. Our corner of the territory technically sits on the Santa Maria Basin within the The Santos Shale, and it is some of the most fertile ground within the span that stretches from the Los Angeles area along the Southern and Central Coasts and through the San Joaquin Valley. The Central Coast could experience an economic boom unlike anything we have ever seen in our lifetimes. If our open spaces and private landowners were to allow fracking to reach its fullest potential, it is estimated by a recent University of Southern California study that it would create 2.8 million jobs statewide by 2020 and increase tax revenues for state and local governments by $4.5 billion per year. Just imagine how that rising tide would lift all of our boats? The economy would be white-hot and opportunity would be endless. Besides, who needs all those tourists anyway? And this is not just pie-in-the-sky, there is a precedent for all of this; for example, the Bakken formation in North Dakota. With less than half of the estimated recoverable oil compared to our Monterey Shale, fracking Bakken has made North Dakota a state that now leads the country in just about every economic measurement. Times are good, business is booming, and everyone benefits. At least for now. Examining a more mature operation in the Appalachian Basin of Western Pennsylvania paints a somewhat different, although sometimes conflicted picture. Drilling and mining are not new to the area and The Marcellus Shale has been fracked for years now. Recently, a preliminary study funded by the US Department of Energy found that fracking has not effected the drinking water there (the EPA expects to release its study late next year). This came as news to many residents in the area who have helped propel the subversive song My Water’s on Fire Tonight, to millions of internet views with its catchy chorus, “What the frack is going on with all this fracking going on?” And, since fracking enjoys almost no regulation plus unique protections under the Uniform Trade Secrets Act, while also being excused from the Safe Drinking Water Act (President Bush omitted frackers in 2005), it may be a long while before Western Pennsylvanians, and the rest of us, do actually know what the frack is going on. Regardless of how you feel about fracking, from an economic standpoint it is working. And many economists give domestic oil and gas exploration and production much credit in helping our country pull through the worst of the Great Recession. And, most astonishing of all, because of fracking, the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that the United States will overtake Saudi Arabia as the world’s largest oil producer by 2017. That means that the energy independence that our policymakers have been fretting about for generations is now within our reach, and it didn’t require that we all buy Toyota Priuses and Teslas. Yet, the IEA’s report continues by chiding the developed world by suggesting that we are “failing to do enough to improve energy efficiency… if those efficiencies were tapped, total energy demand between now and 2035 could be halved, without any decline in living standards.” All of this leaves you and I with a decision to make. How do we feel about fracking right here on the Central Coast? Is it a boom or a bust? Up to this point, hydraulic fracturing has not been practiced in San Luis Obispo County. And, as policymakers struggle to keep up with the rapid pace of exploration, the law is unclear about whether local governments have the ability to ban fracking. One thing is for sure, however, oil companies must secure a permit to drill a new well and the Board of Supervisors has the final say in that regard. So, if fracking is to be either prevented or encouraged here, it will likely happen on the county level. Because once the permits are granted, oil companies are pretty much free to frack at will. But, if recent history is any guide, Big Oil may be in for a Big Fight when it comes to the Central Coast. Such was the case with the band of neighbors in the Huasna Valley who beat back Excelaron’s permit application to drill eight oil wells on private land. In an indication of what is at stake, two days after the supervisors, who bowed to pressure from the Huasnaites, voted to deny its permit, the multi-national energy company filed a $6.24 billion (that’s billion with a “b”) against the county (the case was later tossed by a Superior Court judge). That may be just a warning shot, however, as The Monterey Shale represents a cool $16 trillion. But, as it turn out, the road leading to oil executive nirvana passes right through the San Luis Obispo Board of Supervisors—and if the Huasna Valley skirmish has taught us anything, it’s that our political leaders are listening. SLO LIFE