2 minute read

Curative Setting: Combinations of Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy

neighbouring organs has to be strongly considered and to be weighed against the overall benefits from palliation. The toxicity/efficacy ratio becomes of major importance, but significant improvements in radiation techniques (as outlined above) have led to more favourable treatment profiles, with a general reduction of toxicity for normal tissues surrounding the tumour.

Advertisement

Age itself should not hinder curative approaches in the absence of other significant exclusion criteria for aggressive protocols. Biological age and numerical age do not always correspond. Concurrent application of cisplatin-based chemotherapy to radiotherapy significantly improves local control and thus increases the curative potential of treatment in several solid tumours (e.g. lung cancer, head and neck cancer, oesophageal cancer and cervical cancer). Within the literature, there are several examples showing that dosing schedules of reduced individual cisplatin (CDDP) doses (e.g. 6 mg/m2 CDDP daily application; 20 mg/m2 CDDP q d1–d5; 30 to 50 mg/m2 CDDP once weekly) may be viable alternatives and result in significant benefits in to overall and long-term survival. Combinations of chemotherapy and radiotherapy may have a significant impact on organ preservation (e.g. rectal cancer, laryngeal cancer and cancer of the floor of the mouth). Therefore, concurrent chemoradiotherapy may be an important alternative to extensive surgical intervention, with underlying higher patient risks in the elderly. When deciding on individual treatment protocols in an elderly patient, these alternatives should be acknowledged and discussed within the multimodality team that includes at least a radiation oncologist, medical oncologist, and preferably also a geriatric physician.

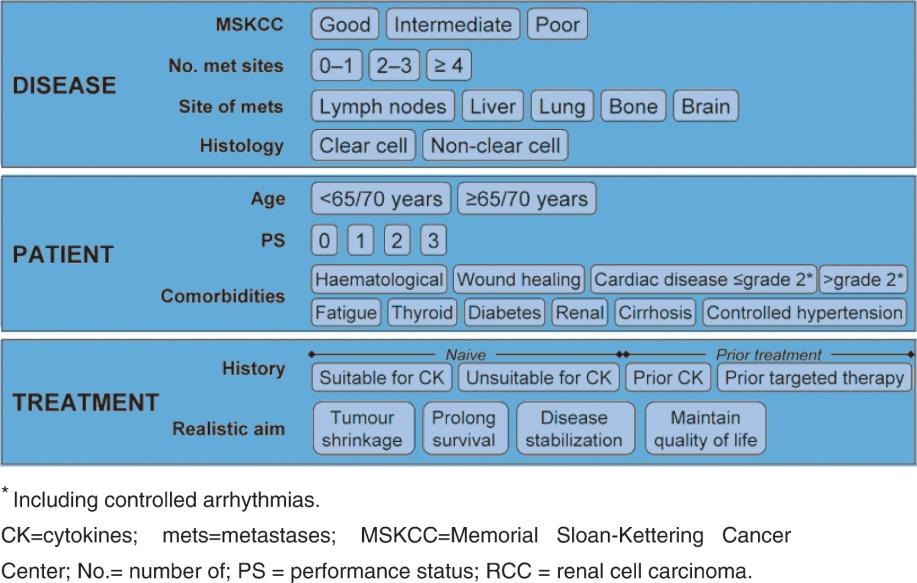

Comorbidities responsible for impaired organ function in the tumour-bearing region can affect treatment tolerance, may lead to significant side effects or even late complications, and may be important patient-related selection factors. Additionally, general comorbidities (e.g. cardiovascular and pulmonary) are significant factors that influence treatment decisions.

Increased side effects, following radiation in the elderly with less tolerance to aggressive treatments, are often considered as major contraindications to radiotherapy. Thus, many elderly patients are either not treated at all or treated with reduced intensities because of expected treatment-related toxicities (e.g. radiation mucositis). These increased treatment-related toxicities may be related to significant comorbidities, such as chronic cerebrovascular and/or cardiovascular disease, arterial hypertension, diabetes, or significant cardiac, renal, and hepatic dysfunction. However, these comorbidities may differ widely in severity, and even when present in combination, they usually do not implicate a strict contraindication to radiotherapy, unless they significantly impact on the overall survival prognosis of the patient compared with the spontaneous course of the disease.