19 minute read

Passage on the Empire Star

BY PETER LUBY

Advertisement

A letter written in haste, in pencil, in the sinking hold of the refrigerated cargo ship, racing down the coast of Sumatra on 13 February 1942.

The writer, Staff Nurse Marjorie Hill, was a masseuse with the 2/13th Australian General Hospital (AGH), one of almost 2,500 passengers fleeing the burning city of Singapore on the Motor Vessel Empire Star.

Also on board was a forlorn little rabbit in a bowtie – a child’s soft toy – now preserved in the Shrine’s Galleries of Remembrance. This poignant relic of Australia’s war in the Far East – eyeless, nameless, separated from its owner – is an emblem of the chaotic, bungled evacuation of civilians from Singapore in the desperate last hours before its fall.

Sister Kathleen McMillan, 2/10th AGH, of Terang, Victoria, picked the toy up as she boarded Empire Star in Singapore on 12 February. Beyond this fact, the rabbit has no provenance – perhaps part of its fascination. With no history of its own it invites imagined back-stories.

Lieutenant Kathleen McMillan, a 10th Australian General Hospital nursing sister, found this toy rabbit near Singapore Harbour wharf in the days before Singapore fell to the Japanese on 15 February 1942

What became of its owner? Did they survive the sinking of the escape ships that ran the gauntlet of ‘Dive Bomb Alley’ in the Bangka Strait? Did the ‘lost’ toy even have an owner? Accounts of the Empire Star’s miraculous escape from Singapore, by some of her lucky passengers, provide some missing pieces of the rabbit’s tale.

Hill and McMillan were two of 130 Australian nurses supporting the 8th Division in Singapore and Malaya in December 1941 when Japanese forces struck. Military and civil leaders believed it would take months for the Japanese to fight through the jungles of Malaya to the gates of Singapore, and that ultimately reinforcements would bolster the besieged city and ‘throw the little men off.’

Misguided confidence fed official reluctance to evacuate the thousands of civilian refugees who flooded into the island city, doubling its population to about one million. General Percival felt that if European women and children – ‘noneffectives’ – were forcibly evacuated ‘the effect on the Eurasian and Asiatic population would clearly be little short of disastrous.’ In truth, the optics of British prestige and control were at stake. In the end, the result was disastrous – relatively few women and children of any racial or social background left Singapore until late January 1942. Despite daily air-raids, everyone thought they were safer in the fortress city. But, against all expectation, within seventy days, Singapore fell.

When Japanese troops landed on the Island on 8 February the mood shifted to panic. Hospitals and civilian homes were being shelled at close range. Early on the morning of 11 February the Australian Nurses were assembled by their Matrons and thirty from each AGH were ordered to take a suitcase and leave immediately for the Singapore docks. Matron Drummond hugged her 2/13th girls goodbye and waved them off with ‘Good-luck Kids!’ Marjorie Hill wrote:

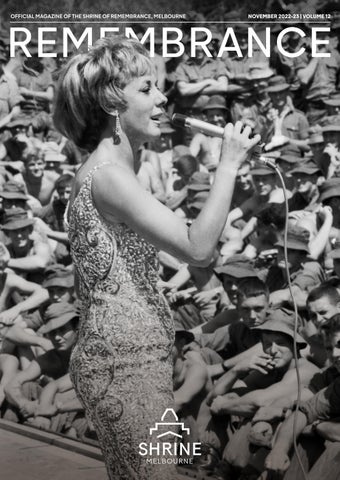

Troops on the deck of the Empire Star. (Donor R. Sayers)

Reproduced courtesy of the Australian War Memorial (P01117.008)

The palls of black smoke came from burning warehouses full of rubber, blazing offshore oil depots and the abandoned Naval Base; fires lit as part of a scorched-earth policy. Japanese planes circled high above, and air-raid sirens wailed. Cars packed with evacuees and luggage crawled toward the waterfront, past rubble and burnt-out vehicles, fallen telegraph poles and tangled power lines.

Also heading for the harbour was Carline Reid, a Tasmanian who had worked for the Local Defence Corps in Malaya before fleeing to Singapore. Dismissed from her role at Malaya Command, she was handed a pass for a ship leaving at 1pm: ‘Please allow Miss Reid to proceed on board the E.S as a member of the Royal Corps of Signals party.’ At 12.30pm she was driving her little Austin Seven through ‘streets and streets of absolute desolation’:

Informal group portrait of members of the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) in the air raid shelter in the hold of the cargo vessel, Empire Star after their evacuation from Singapore

Reproduced courtesy of the Australian War Memorial (PO3315.012)

Reid stopped to ask directions from a straggling group of soldiers.

She continued on, past a long line of abandoned cars with their doors wide open, and finally reached Clifford Pier. She showed her pass to an armed sentry and squeezed through the gate. It was 12.55pm.

MV Empire Star only had cabin space for sixteen passengers, but over 2,000 people were now crowding toward her gangway: 1,573 military evacuees, mainly British and New Zealand Air Force ground crew and technicians needed to continue the fight in Java; about 40 British nursing sisters with 80 stretcher cases; and a crew of 88. There were at least 164 civilians and 35 young children. Not even the ship’s master, Selwyn Capon, knew the exact numbers. At this stage he was letting any civilian, any woman without a ticket, board his ship.

Capon was a skilled Merchant Mariner who was awarded an OBE for distinguished service in the First World War. He’d reached Singapore on 29 January with BM11, one of the last military convoys, bringing arms, equipment and 17,000 reinforcements of the 18th Division (they would walk into captivity 17 days later). Today, from the bridge, he watched troops rolling abandoned cars and trucks to the edge of the pier and pushing them into the sea.

Ambulances carrying the 2/13th Nurses reached the crush on the pier. Staff Nurse Phyllis Pugh, of Brisbane, recalls being ‘assisted from the swaying gangplank by two merchant seamen on to the Empire Star, which had previously been used in evacuating troops from Greece and Crete.’

Australian nurses on deck of SS Empire Star approaching Fremantle, Western Australia

Image courtesy of Australian War Memorial (P09909.030)

Hill thought she was with:

Meanwhile, Carline Reid wrote that she was surrounded by people from across the world ‘wearing anything from shorts, slacks, every kind of dress, to Chinese pyjamas…’

Maude Spehr, 2/13th AGH, remembers:

Children on Singapore wharf being evacuated from the city before the island was taken by Japanese. Girl is holding doll and boy several flat boxes, possibly board games

Reproduced courtesy of State Library Victoria (H00.200/688)

Reid confirms:

Nurses from the 2/10th AGH arrived and were pressing through to the gangway. Captain Sinclair RNR, commander of convoy escort HMS Kedah, recalls the wharf:

Here, Sister McMillan spotted a little toy rabbit under foot and gathered it up, thinking its young owner was already onboard.

Phyllis Pugh

At sea, off Singapore, 1942-02-12. members of the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) in the hold of the cargo vessel Empire Star, being evacuated from 2/10th Australian General Hospital. Left to right: Sisters Satchell, Gibson, Gethla Forsyth, ship’s steward, Garrood, Bentley. Sisters Garood and Bentley were from the 2/13th AGH

Reproduced courtesy of the Australian War Memorial (P01117.006)

Hill remembers ‘there was just room for us to lie down in the hold and we lay flat on ground sheets and sweated as I have never sweated before.’

Out on the harbour on HMS Jarak, Lieutenant Commander Curry RNVR heard the drone of planes – 27 twin– engine bombers approaching from the east. He was horrified to see:

Offshore on MV Penna, Tom Simkins RN saw:

An anti-aircraft gun firing from the wharf rocked the ship as the planes came over.

Informal portrait of, left to right, SX13081 Sister (Sr) Elvin Wittwer, 2/13 Australian General Hospital; WX11173 Sr Sara Baldwin-Wiseman; Captain Capon, SS Empire Star and TX6022 Sister (Sr) Hilda Hildyard

Reproduced courtesy of the Australian War Memorial (P09909.32)

Curry thought of the defenceless children on the pier.

‘Stragglers’ who’d been milling around on the pier all day, watching the Empire Star, now sensed their last chance to escape the blazing city. Military Police held the more forceful back at gunpoint, but some parties, identified as ‘Australians,’ pushed past and streamed up the gangway. Chief Officer Dawson saw ‘panic at the shore end of the gangway’ and went there to quell it, telling the men: ‘this ship was reserved for RAF personnel, women and children. Eventually these Australian troops quietened down and we were able to proceed,’ but others were out on the water in small boats, looking for any way to get on board. Capon ordered ‘gangway up’ and lines cast off.

As the ship’s engines roared to life an Australian Sergeant was trying to haul himself up a mooring rope, onto the ship. A shot rang out from the pier, and he splashed down into the water. An RAF Corporal saw a woman with a small boy pushed aside by twenty Australians who surged up onto the ship.

Flight Sergeant Harry Griffiths, 453 Squadron RAAF, was one of hundreds of men drawn to the docks that morning. Recovering from injuries in hospital, he’d fled as the Japanese closed in and stumbled, exhausted and feverish, into a deserted hotel. Sitting at the bar drinking water, he felt a tap on his shoulder and a voice said, ‘get to the docks - a ship is leaving.’ Griffith turned, but no one was there. He staggered in a daze toward the waterfront, putting his hands on the gangway of the Empire Star just as her crew were pulling it up.

Informal portrait of TX6022 Sister (Sr) Hilda Hildyard, Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS), hanging washing in the hold of SS Empire Star. Sister Hildyard was one of sixty Australian nurses evacuated from Singapore aboard SS Empire Star in February 1942

Reproduced courtesy of the Australian War Memorial (P09909.31)

It was now 6pm and dark. The harbour was bathed in the lurid glow of burning fuel dumps, but it was still too dangerous to move through the minefields. Empire Star and fourteen other merchant ships waited in the Roads till dawn, when HMS Kedah, cruiser HMS Durban and two destroyers led the convoy out into the Durian Strait. Just after 9am alarms were sounded, and six Japanese dive bombers descended on the Empire Star.

Carline Reid

The ship’s machine guns hit one plane as it came in low. It spiralled into the sea trailing black smoke and flame. Reid recalled, ‘Children screamed incessantly, and terrified mothers tried to comfort them. A few people passed out now and then, but we never knew if it was caused by fear or heat…’

A second plane was hit and broke off over the horizon, pouring smoke.

Maud Spehr

Carline Reid

The ship received three direct hits; fires broke out in some of the cabins and a lifeboat was wrecked. Fire parties pushed through the crowded decks to extinguish the blazes. Australian nurses, including Phyllis Pugh, ‘quickly made dressing stations down in the hold and very soon wounded were brought down to us.’

Marjorie Hill

Staff Nurses Margaret Anderson and Veronica Torney were tending wounded below deck when cabins started filling with smoke. They dragged the wounded up top, believing the danger was over, but Japanese planes returned and flew low, strafing the ship with machinegun fire. Anderson and Torney shielded the wounded men with their own bodies as bullets spattered the decks.

Phyllis Pugh

Group portrait of nurses of the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) after disembarking from Empire Star. Known to be in the photograph are: M Adams; QX22814 Lt Margaret Constance Selwood; VFX59690 Sister Sheila Daley (fourth from left); QFX22715 Sister Julia Elizabeth Blanche Powell; QFX19069 Captain (Capt) Irene Dorothy (Dorothy) Ralston; Sister Pugh (probably QFX22716 Lieutenant Phyllis Pugh)

Reproduced courtesy of the Australian War Memorial (P03315.015)

For three more hours, twin-engine bombers high overhead harried the ship as the captain took ‘violent evasive action.’ Crew lay on their backs on deck, watching the bombers through binoculars, calling out their angles of attack so that Capon could turn his ship at the last moment – as the bomb-bay doors opened. Engines were thrown into full reverse to dodge the fall of bombs.

After sustained attacks from over 50 aircraft, the last wave of nine bombers came over at 1.10pm.

Phyllis Pugh

Fourteen were dead and seventeen wounded. Carline Reid assisted with the wounded:

Carline Reid

Engineers made urgent temporary repairs as the ship plodded on toward Java. Captain Capon rewarded the bravery of the nurses by granting them the use of his bathroom

Phyllis Pugh

Carline Reid

Towards evening, Pugh ‘saw the burial at sea with full military honours for thirteen men… at this burial service they sang Abide With Me. If I hear it today, I still get a lump in my throat…’ After dark, they passed a strung-out convoy of the slower, smaller ships that had left Singapore before them on 11 February. How many of these made it through safely is unknown, but only three of the fifteen in the Empire Star convoy survived the Bangka Strait.

After 40 hours at sea Empire Star limped into Tanjong Priok, the port for Batavia. Military police came aboard and marched off 139 Australians who had embarked ‘without authority’ in Singapore. The fate of these men is unclear. Probably they were organised into the Australian units that stayed to defend Java from the Japanese. Many likely perished in captivity.

While Empire Star was undergoing quick repairs, they received news.

Carline Reid

Five unidentified Australian nurses washing in the hold section of SS Empire Star

Reproduced courtesy of the Australian War Memorial (P09909.006)

Most of the civilian evacuees transferred to other ships, but the Australian nurses were still on the Empire Star when she got under way and headed for Sunda Strait on 16 February. She arrived in Fremantle, ‘10am-ish’ on 23 February, where the local Red Cross met the evacuees with fresh clothing and provisions. Margaret Hamilton (2/10th AGH) recalls, ‘as we said goodbye to Captain Capon, he asked us to do two things every day of our lives: we were to thank God we were alive, and to never forget the Merchant Navy.’

As the Australian sisters left his ship, he wept. ‘Strange as it may perhaps seem,’ he later wrote, ‘nevertheless perfectly true, there are times when, deep down, I’m apt to be somewhat emotional...’

Eight months later, on a run to South Africa, Empire Star was sunk by a U-boat in the mid-Atlantic. Most of the crew and passengers got off into three lifeboats, drifting for two days in heavy seas. Two boats were rescued by the Royal Navy, but the third – carrying Captain Capon, and 37 others – was lost.

The Empire Star nurses dispersed to their home states, and to serve in military hospitals in New Guinea, Borneo, and Australia. Some went back to Singapore in September 1945 to rescue the pitiful, emaciated survivors of the Vyner Brooke, the ship that took the remaining nurses of the 2/10th and 2/13th Hospitals from Singapore on the Black Friday before it fell. Only 24 out of 65 had survived brutal treatment and captivity under the Japanese.

Staff Nurses Vera Torney and Margaret Anderson, awarded for bravery during Empire Star air attacks

Reproduced courtesy of the Australian War Memorial (P09909.30)

Two Victorians were given awards for bravery and devotion to duty in the air attacks on the Empire Star. Sister Vera Torney was awarded a military OBE, and Sister Margaret Anderson became the first member of the AANS to receive the George Medal, usually given ‘for acts of great bravery in a non-war setting.’

To the Australian nurses MV Empire Star was always the ‘Lucky Ship,’ for obvious reasons. Margaret McMillan never managed to reunite her lucky little rabbit with its imagined owner. It survives, in the Shrine’s Collection, a mute but eloquent symbol of the loss of Singapore, of the few who made it out and the many who didn’t.