3 minute read

Making art from war

BY TESSA OCCHINO

Isaac William Benson, Gunner for the 12th Field Artillery Brigade, was one of thousands of First World War soldiers to bring home souvenirs from their time overseas. Souvenirs ranged from beautifully made jewellery and carved letter openers to large models of tanks and beer mugs, but many had the common attribute of being made from salvaged wartime material.

Today known as trench art, these objects were made from spent bullets, barbed wire, shell casings, coins, and salvaged helmets. They varied in size from small rings through to large, and rather inconvenient to transport home, sculptures.

Family legend suggests Benson brought the shell cases back from the Western Front. The shells are 1916 and 1917 18-pound rounds and feature engravings of Australian flora and fauna, including gum trees, kangaroos, koalas, emus, and native birds. Written across the middle of one shell is ‘Souvenir of France 1916 - 1919’. Ammunition casings were made of brass, so the silver coating of these shells is particularly special, showing an extra level of craftmanship.

Some examples of trench art were made by the soldiers themselves to pass the time between duties and battles. Daily life at the front, although always potentially dangerous, was often routine and boring. When official duties were done, Australians had downtime to fill, which they did by writing letters, playing cards, reading and, in some cases if they had the skill, making trench art.

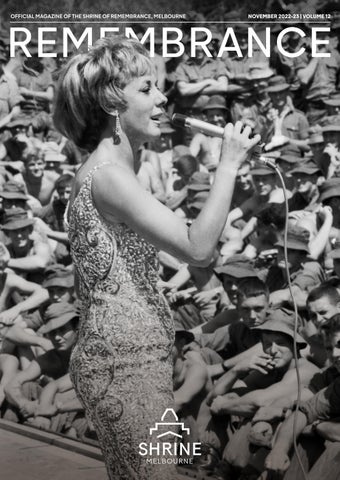

Gunners of an Australian battery use an 18 pounder British field gun to rain ‘barrage fire’ on the enemy trenches, July 1916 Pozieres. The shells in this image show what Benson’s souvenir looked like before it was plated and engraved.

Reproduced courtesy of the Australian War Memorial (EZ0141)

It is likely that smaller whittled wood and bone works, or works made of bone, were made in the trenches and that larger or more intricate works made from salvaged metal were made behind the frontlines or in local souvenir factories.

These two intricately engraved, white metal plated spent ammunition shells were probably not made by Benson, but rather by the booming local French souvenir industry that emerged to service the soldier tourist market. This industry created popular gifts for those at home, building on established traditions, such as embroidered post cards and cushion covers, and expanded into new ones, making cigarette cases, sculptures and good luck charms.

Many manufacturers in these conflict zones pivoted to souvenir production as a means of survival. Normal, prewar industry was suspended with the arrival of conflict, manufacturing supplies were scarce and import and export nearly impossible. Factories and workers turned to creating things with what they had—salvaged war material—and targeted their only market: soldiers. This was also a way to help people who were displaced by war earn an income after fleeing from their homes with nothing.

Benson returned to Australia in April 1919, and sometime between his return and the item donation in 2020, they were filled with cement and used as door stops by the Benson family.