7 minute read

BEST OF THE BLOG: What we’re saying online

best of the blog

BEST OF THE BLOG

Advertisement

Check out the great debates on the Shameless blog. Join the conversation at shamelessmag.com.

HEY, PROGRESSIVES: PLEASE STOP BEING JERKS ABOUT DISABILITY (EXCERPT)

Originally published on February 12th, 2021 by Denise Reich

Dear fellow progressives,

If you advocate for positive, inclusive advances in society, believe in equality and social support, think science and climate change are real, support LGBTQ+ rights and do not believe religion should dictate public policy, I’d like to chat with you for a moment.

We need to talk about ableism and lack of accessibility in progressive spaces. There’s still too much of the former and not enough of the latter. We’re supposedly on the same side, striving for the same ideals, but some of you still treat disability as a flaw, an insult or an inconvenience. It’s been four long years since the original charter of the Women’s March referred to disability as a burden. It’s now 2021. Why are we still doing this?

What made me angry? Maybe it was the the U.S. congressman who claims he respects his constituents, but made a video – filmed by his kids – mocking hand tremors.

Maybe it’s the way a podcast with a transcript is as rare as a unicorn.

Maybe it’s the way words like “crazy” and “dementia” are freely thrown around as pejoratives.

Maybe it’s the people who insist that illness can be cured by diet and exercise, so if we all followed the Paleo Carb Free Super Seaweed Probiotic Diet, bought only organic food and did yoga, we wouldn’t need healthcare.

Maybe it was the non-profit supposedly about “self-acceptance” that gaslit me when I requested accommodation for an activity, and then made public passive-aggressive comments about it.

Maybe it was reading of that New Zealand restaurant chain that tried to “start a conversation” by substituting an ingredient – that was a potential allergen – without informing its customers. Or that Manhattan restaurant that deliberately served food with high-gluten flour to customers who requested gluten-free meals.

Maybe it was hearing about companies that refused to accommodate disabled people’s requests to work from home but, when the pandemic began, arranged full-time telecommuting for every single employee.

Maybe it’s all of the above. Maybe it’s the collective negative impact on the disabled people who experience these slights firsthand or witness them, and the way it contributes to stereotypes as a whole. Maybe it’s the painful realization that the negativity and stigma surrounding disability are often fuelled by those who claim to be allies.

The Cambridge Dictionary gives a simple definition of ally: “Someone who helps and supports someone else.” With allies like these, do we need enemies?

As a disabled person, one comes to expect that allyship is tenuous at best. Disabled people are welcomed when we’re “inspiring” in a way that makes abled individuals feel good about themselves. If we can conceal all evidence of our disability or illness so those around us don’t have to consider it, we’re golden. However, if we request accommodation of any kind or share concerns that we’re not being treated respectfully, we’re shunned. Worse, people often react viscerally if we don’t laugh along with our own denigration. They don’t even consider the possibility that they’re doing any harm or alienating disabled people.

On the right side of the political spectrum, we have people actively trying to kill us by removing assistance for disabled people or insinuating that our lives are “expendable.” The pandemic has made that even more painfully obvious. The death toll from COVID-19 is often downplayed with the rejoinder “but they had pre-existing conditions,” as though that makes lives less valuable.

On the left we have you, our supposed allies. However, when it comes to interaction on a personal level, your allyship often seems to exist more in theory than in practice. Sure, you’ll vote for that law expanding benefits for disabled people, but then you’ll turn around and share ableist memes on social media or accuse someone of “faking it” because they are an ambulatory wheelchair user. Do you even realize the dichotomy there?

This has not swayed me in any way from actively supporting progressive political ideals and candidates, because the goals are still very important. I am hopeful that the majority of people who support progressive platforms actively strive to do better. Doesn’t the label inherently reflect an openness to progress?

As time goes on, I find that, for my own self-care, the majority of my support for the progressive movement occurs in the absence of meaningful dialogue and social interaction with the non-disabled community. I don’t trust you anymore, and I’m exhausted by the casual ableism many of you exhibit. After all, if you have not bothered to make your events and outreach programs accessible, you clearly don’t want me there anyway.

Progressive community, do you actually want to be inclusive, or just claim that you are because it sounds good? I’d like to believe it’s the former.

If you want to truly be allies to ill and disabled people, you need to start paying attention to the harm it does when you denigrate disability. Stop talking over disabled people. Listen more. Let your allyship be something tangible, not meaningless words.

No love whatsoever, Denise

LEARNING TO BE AN ALLY IN INDIGENOUS ACTIVISM (EXCERPT)

Originally published on April 8th, 2021 by Raiyah Patel Kindness and fairness are simple, basic ideas taught to most of us at an early age. But I only began to understand what they meant after hearing about Shannen Koostachin.

Shannen, a member of the Attawapiskat First Nation, wanted to attend a school with adequate facilities. She pleaded with the Canadian federal government to build a school in her community, but her initial demands were met with silence. Shannen tragically died in a car accident in 2010, but her activism led to the building of the Kattawapiskak Elementary School in 2014. Her activism also inspired the youth-led campaign “Shannen’s Dream” that contin-

ues to advocate for equal education for all Indigenous children.

Shannen’s story found me in Grade 2, and forced me to question why I don’t have to worry about schooling, while others – like Shannen – have to fight for basic rights that should be guaranteed. It seemed obvious that Shannen’s struggle was a result of unfairness, or what I later came to understand as injustice. Shannen’s work inspired me to advocate for Indigenous children who faced similar injustices.

I had good intentions, but quickly learned that I could not understand Shannen’s struggle. I could never experience the pain and injustice caused by colonization’s legacy, or the unfairness of having inadequate schooling. So how could I confront the injustice I witnessed? This question helped me realize I could ally with Indigenous-led movements.

First, I found a mentor within the Indigenous community. Finding a mentor is an important step to becoming an ally because it encourages listening and learning. Indigenous cultures place great emphasis on the storyteller as part of an oral tradition that passes knowledge down to younger generations. We can learn from these traditions when we engage with Indigenous cultures.

My most important mentor has been Dr. Cindy Blackstock. Dr. Blackstock is the executive director of The First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada. Cindy successfully launched a human rights case against the Canadian government arguing that they discriminated against First Nations children by underfunding the on-reserve child welfare system. Dr. Blackstock helped me understand that you don’t need to experience injustice to recognize and address it. She continues to encourage my activism and welcomes contributions I make to Indigenous-led movements.

Cindy’s mentorship combined with my growing activism made me see that social movements succeed only with help from the larger society. Cindy and Shannen are not just victims of injustice. They are the storytellers that define injustice and motivate us to advocate for change.

Allies are needed for these campaigns. If you want to become an ally to Indigenous activism, here are some Indigenous-led movements that you can support:

Jordan’s Principle honours Jordan River Anderson and addresses the inequities faced by Indigenous children when they seek public services. It ensures public services administered to Indigenous children take into account the cultural needs and history of a colonized peoples.

The Assembly of First Nations has a policy initiative dedicated to addressing the disproportionate amount of violence faced by Indigenous girls, women and two-spirited people. They seek the development of a national action plan to end violence against Indigenous women and girls.

The Spirit Bear campaign engages youth activists by providing resources to learn about discrimination against Indigenous children. Spirit Bear has a book and a movie to teach children about The Human Rights Tribunal and how they can support the campaign.

The most important part of being an ally is knowing that learning and growing is a process. My understanding of unfairness was nurtured and deepened when I learned about those in our society who are not as privileged as I am. I also learned that those most harmed by injustice welcome the help of others. My journey is not complete; I continue to learn and listen on my way to becoming an effective ally.

Voices from the margins.

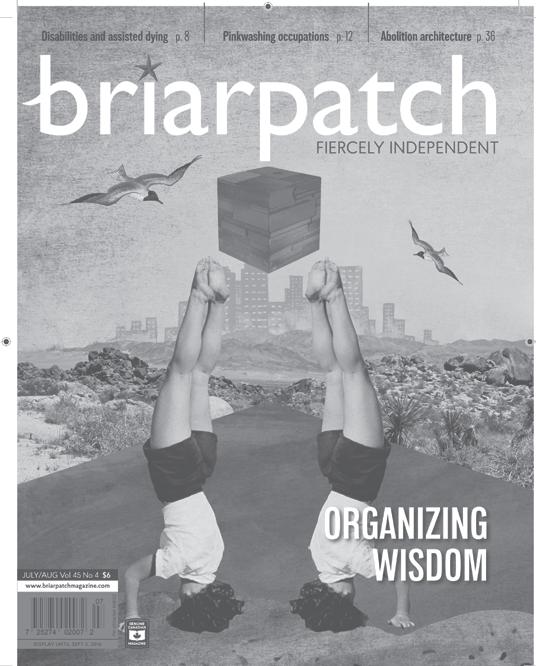

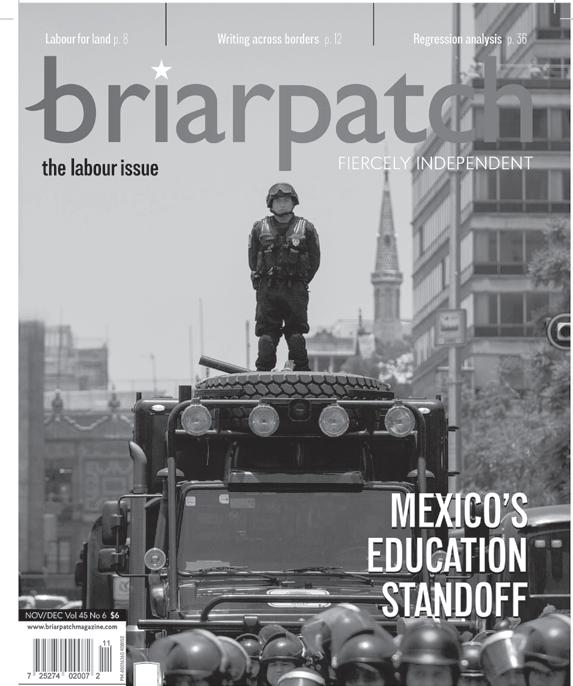

Subscribe today at briarpatchmagazine.com

Commit & save! One year for $29.95 Two for $49.95 Three for $69.95