4 Hot off the Press Plays About Obstacles by Zackary Ross

6 Outside the Box: Design/Tech Solutions

Stops on Stage: Searching for a Braking Breakthrough by David Glenn

64 Words, Words, Words … Review of Toward a Future Theatre: Conversations During a Pandemic, by Caridad Svich review by Joseph R. D'Ambrosi

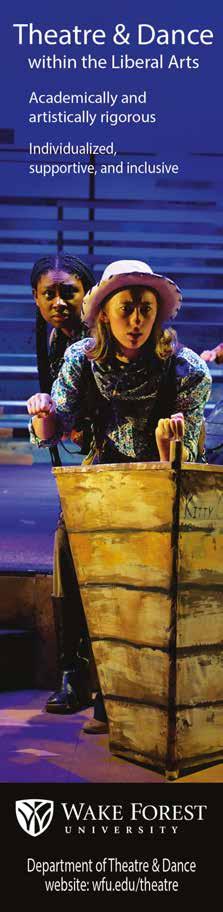

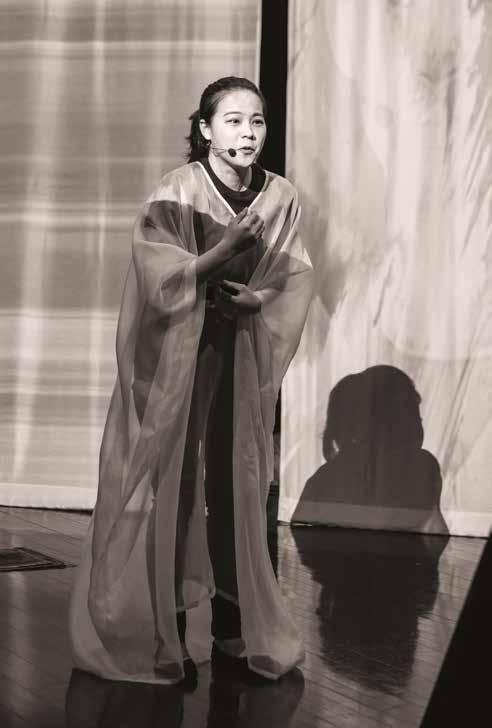

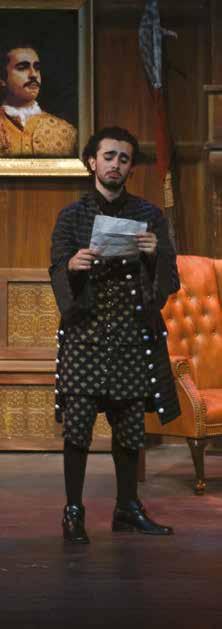

Marie (right), played by Devon Grice, travels with her daughter Rose Marie, played by Maya Moreau, on a prospective college visit in the world premiere of A Complicated Hope by John Mabey, the 2022 winner of SETC’s Charles M. Getchell New Play Award. The play, directed by Paul Truckey, was presented at the James A. Panowski Black Box Theatre at Northern Michigan University in Marquette, MI. See more, Page 58. (Photo by Fischer Genau; cover design by Deanna Thompson)

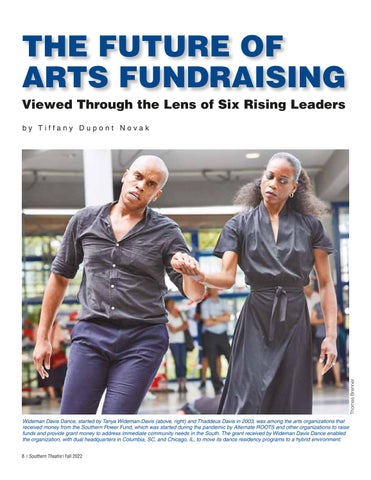

8 The Future of Arts Fundraising

Viewed Through the Lens of Six Rising Leaders

by Tiffany Dupont Novak

26 A Play for All Seasons

Colleges Share the Key Factors They Consider in the Show Selection Process

by Tom Alsip

40 Playwriting in the Pandemic

Much Was Lost, and Much Was Found by Laura King

interview by Laura King

Read an excerpt from A Complicated Hope, the 2022 winner of the Charles M. Getchell New Play Award, given by SETC to recognize a worthy new play.

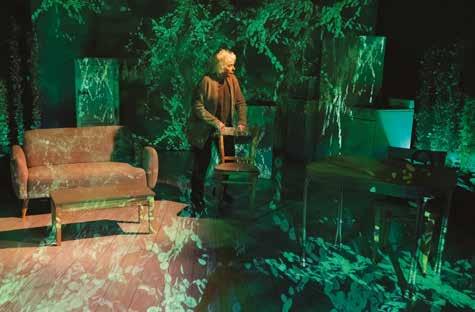

Marin Theatre Company/ The CatastrophistOur regular column on plays that have recently become available for licensing focuses in this issue on works about characters working their way through an unanticipated turn of events.

by Zackary Ross

by Zackary Ross

Life is full of curveballs and unexpected twists, yet we venture forward, learning more about ourselves and the people we surround ourselves with through the process of the journey. The plays featured in this column present their protagonists with unusual circumstances and dramatize the resulting emotional and psychological journey they experience. To develop the following list of suggested titles, we surveyed major play publishers’ offerings during the last few years. Following each description, you’ll find information about the cast breakdown and a referral to the publisher who holds the rights.

In the middle of the Great Depression, four Canadian women set out to form an all-female hockey team. This heartfelt play explores each character’s personal narrative and captures the social and political climate of the times in an imaginative piece of staging that incorporates Jazz Age music and dance. The play is based on the real-life Preston Rivulettes, which formed in the 1930s.

Cast breakdown: 4 women (any ethnicity); 1 man (any ethnicity)

Publisher: Concord Theatricals www.concordtheatricals.com

It’s time for the Schuster family’s annual horseshoe tournament, but host Adam is unprepared to deal with the drama that ensues as he is confronted with his father’s declining health, a feud with his younger brother, and problems in his marriage, all of which complicate the fun summer outing. Secrets emerge, family bonds are tested, and the family’s path forward is uncertain in this dark comedy.

Cast breakdown: 3 women (any ethnicity); 4 men (any ethnicity)

Publisher: Dramatists Play Service www.dramatists.com

Few Black people live in Paris, VT, a fact that is keenly felt by young Emmie, who lies to get a job at a local superstore called Berry’s. As is the case with the rest of the employees, desperation for a paycheck has led Emmie to work for a corporation that regularly promotes the underpaid poor to slightly less-underpaid middlemanagement positions and asks them to help subjugate those under them to protect profits. This poignant drama explores the side hustles, unrealistic dreams and resignation felt by members of the working class.

Cast breakdown: 3 women (1 Black/ African descent, 2 white/European descent); 4 men (1 Black/African descent, 3 white/European descent)

Publisher: Concord Theatricals www.concordtheatricals.com

Fifteen-year-old Simon sits on his fire escape, dreaming up a superhero who will rescue him from the life of a teenager. Simon’s father passed away and, rather than deal with his grief, Simon loses himself in his superhero fantasies, further distancing himself from his mother Charlotte. As

Simon’s landlord and other tenants in the building enter the story, Simon begins to comprehend the complexity of the world’s true superheroes in this charming musical.

Cast breakdown: 3 women (any ethnicity); 5 men (any ethnicity)

Publisher: Concord Theatricals www.concordtheatricals.com

When Rachel inherits her Great Aunt Ida’s beloved New England bookstore, she can’t fathom taking ownership of the business and managing it, so when the offer to buy it and turn it into an apartment complex comes around, Rachel is tempted to sell. However, the more time she spends in the shop with its unusual employees and charming clientele, the more her resolve begins to waver.

Cast breakdown: 3 women (any ethnicity); 3 men (any ethnicity), expandable to 28 total actors

Publisher: Playscripts, Inc. www.playscripts.com n

Zackary Ross (he/him) is an associate professor of theatre and arts administration program director at Bellarmine University in Louisville, KY. He is a member of the Southern Theatre Editorial Board.

Clay Thornton, clay@setc.org

Southeastern Theatre Conference

5710 W. Gate City Blvd., Suite K, Box 186 Greensboro, NC 27407 336-265-6148

Laura King, Chair, Independent Theatre Artist (GA)

Becky Becker, Clemson University (SC)

Jennifer Goff, Centre College (KY)

Gaye Jeffers, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga

Ricky Ramón, Howard University (DC)

Chalethia Williams, Miles College (AL)

Tom Alsip, University of New Hampshire

Keith Arthur Bolden, Spelman College (GA)

Amy Cuomo, University of West Georgia

F. Randy deCelle, University of Alabama

Kristopher Geddie, Venice Theatre (FL)

David Glenn, Samford University (AL)

Scott Hayes, Liberty University (VA)

Edward Journey, Independent Artist/Consultant (AL)

Stefanie Maiya Lehmann, Lincoln Center (NY)

Sarah McCarroll, Georgia Southern University

Tiffany Dupont Novak, Actors Theatre of Louisville (KY)

Thomas Rodman, Alabama State University

Zackary Ross, Bellarmine University (KY)

Jonathon Taylor, East Tennessee State University

Chalethia Williams, Miles College (AL)

Student Member: Chris Cates, Wake Forest University (NC)

Catherine Clifton, Freelance Copy Editor (NC)

Denise Halbach, Independent Theatre Artist (MS)

Philip G. Hill, Furman University (SC)

Salem One, Inc., Winston-Salem, NC

Southern Theatre welcomes submissions of articles pertaining to all aspects of theatre. Preference will be given to subject matter linked to theatre activity in the Southeastern United States. Articles are evaluated by the editor and members of the Editorial Board. Criteria for evaluation include: suitability, clarity, significance, depth of treatment and accuracy. Please query the editor via email before sending articles. Stories should not exceed 3,000 words. Color photos (300 dpi in .jpeg or .tiff format) and a brief identification of the author should accompany all articles. Send queries and stories to: deanna@setc.org.

Southern Theatre (ISSNL: 0584-4738) is published three times a year by the Southeastern Theatre Conference, Inc., a nonprofit organization, for its membership and others interested in theatre. Copyright © 2022 by Southeastern Theatre Conference, Inc., 5710 W. Gate City Blvd., Suite K, Box 186, Greensboro, NC 27407. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or part without permission is prohibited.

Subscription rates: $24.50 per year, U.S.; $30.50 per year, Canada; $188 per year, International. Single copies: $8, plus shipping.

From the SETC PresidentTThe desire to create theatre only feels more present with every step we take out of the lingering pandemic. As many of the stories in this Southern Theatre tell it, those makers who have decided that everything has changed are the ones who are making bold moves toward equity, justice, and accessibility in the theatre.

When COVID-19 shut down live theatre, playwrights wondered when their work might once again be seen on stage. More than two years after the pandemic began, writers continue to struggle, but many have carved new paths, creating online works and monologues, and some are seeing a return to onstage produc tions of their work. Laura King details the playwrights’ pandemic story.

One of the playwrights who saw doors open in 2022 was John Mabey, who won SETC’s Charles M. Getchell New Play Award with their new play A Complicated Hope. By August, Mabey’s play had not only had a reading at the SETC Convention, but also two productions onstage. Mabey discusses their work in an interview with Laura King, and we share an excerpt from the winning play.

The ongoing pandemic and calls for social justice have impacted theatres’ fundraising efforts, with many looking for new ways of approaching philanthropy that address systemic racism and inequity. Tiffany Dupont Novak interviews six rising leaders in the field who share insights on how arts leaders can redefine philanthropy in their organizations.

The impact of the pandemic is also the jumping-off point for the book featured in our “Words, Words, Words…” column. Joseph R. D’Ambrosi reviews Toward a Future Theatre: Conversations During a Pandemic, by Caridad Svich, which includes interviews with more than 50 theatre makers and performance artists about their pandemic lives and the future they see for theatre.

Every college or university does it, but there’s no set way they all do it. “It” is the annual season selection process. Using information gleaned from a survey of school representatives, Tom Alsip looks at how different schools build their seasons, what their key considerations are, and who typically is involved in the process.

In our regular “Hot off the Press” column, Zackary Ross shares some recently published plays that feature characters overcoming the unexpected obstacles that life has thrown in their path. Finally, in our “Outside the Box” column, which features innovative design/tech solutions, David Glenn details how to create a low-cost braking solution for use on rolling scenery wagons.

Embracing big change, relishing small miracles, and growing through reflec tion are key components to the forward progress of our industry. Let these stories inspire you to carry out change in your own ways, while caring for the community that is nearest to you.

Maegan McNerney Azar (she/her), SETC PresidentSmooth scenic transitions often rely on rolling scenery wagons. The two biggest factors in a seamless transition with wagons are the quality of the casters and the strength/surety of the brakes that make the unit static. The more easily that the wagons roll, the harder they are to make stationary, or brake. Braking solutions come in many forms, from complex pneumatic rigs to simple wedging of the platforms, but this problem of making dynamic moving units become perfectly still is a challenge on every production that attempts these transitions.

Specialized brakes are available through most scenic hardware distributors, but they are often expensive and noisy. A common substitute for these brakes is push/pull clamps, with the most common brand being DeStaCo. These red-handled clamps are often seen bolted to wagons in an attempt to brake the rolling scenery.

Push/pull clamps offer consistent lifting power that can be custom-ordered based on the strength and stroke length needed for a project. Their lifting strength can range from 100 pounds to 7,500 pounds, and their stroke (travel distance) can range from ¾" to 4".

The biggest issue with using them in this fashion is the small contact point with the stage. On a larger wagon or one that is going to have actors stepping on and off, this contact point is most often insufficient for the task. More brakes can be added, but despite their strength, they struggle to secure the unit.

I began experimenting with ways to address this problem. My first experiment was adding a plywood plate to the end of the linear clamps. The clamps have stan dard threading in the push rod that allows you to insert any type of standard threaded

bolt. The larger the clamp, the bigger the bolt size. While the adding of a plywood plate to the brake allowed me to create a larger contact surface, the plywood was constantly trying to turn, which would loosen the bolt. No amount of thread lock or additional “keeper” nuts would stop this turning.

The breakthrough (brakethrough?) for me came when I attempted to make a larger brake for a streetcar wagon that was going to be carrying several actors in a produc tion of On the Town at Samford University.

I decided on a brake length of about 4' and saw pretty quickly that I would need to add a second push/pull clamp for that large of a contact point. After attaching the two brakes to the piece of wood, I realized that adding a piece of steel between the handles would allow the shift crew to drop a single brake.

After connecting the two clamps to the board, I noticed that each clamp kept the other clamp from loosening its respec tive bolts. The major problem that I had

previously faced – with the bolts backing themselves out – was solved. A simple lock washer was the only thing needed to ensure that the bolts stayed firmly in place.

While the wooden foot of the brake was probably sufficient by itself, I looked for a rubber material that could be easily attached to help provide increased friction. I chose rubber drawer lining commonly found at Lowe’s or Home Depot near the tool chest section. The material is very pli able, low-cost, and easily replaced when it has exceeded its life span.

For the brake, I chose the DeStaCo Model 610 with 800 pounds of lifting strength and a 1 5/8" travel. At a minimum, I would recommend a set of clamps with at least a 300-pound push/pull strength, as the metal frame on a smaller clamp might bend under the stress. The Model 610 also works well due to the unique shape of its handle. The “T” at the end of the handle helps facilitate the attaching of the metal that connects the clamp handles. However, if you remove the red outer jacket from any DeStaCo clamp, the metal of the handle

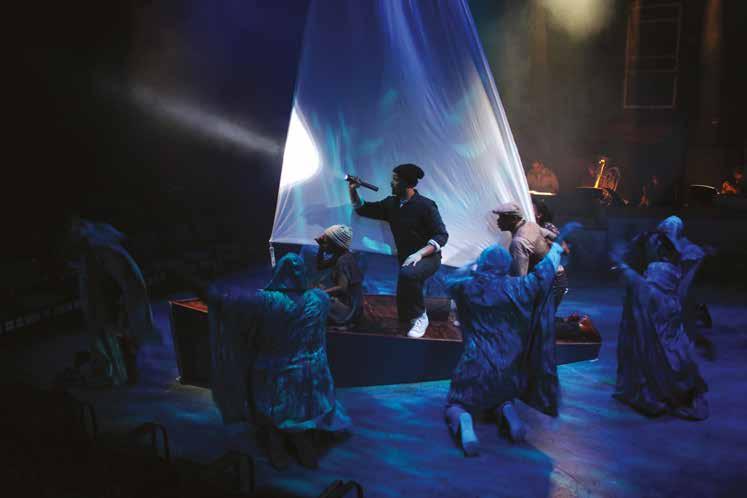

outside the box The need to create a large brake for the streetcar in this Samford University production of On the Town, with scenic design by Eric Olson, inspired the discovery of a low-cost solution.Step 1: Cut the board that will act as the contact point to desired length and countersink for bolt heads.

Step 2: Attach the DeStaCo clamps by tightening bolts into their threaded inserts.

inside can be easily bolted through.

In looking for a piece of hardware that could connect the handle to the steel, I found that the U bolt from a ¼" wire rope clip fit perfectly over the Model 610 handle.

With the drilling of two small holes for each clamp through a piece of angle steel, the clamps were securely connected. The clamps can be spaced as far as 4' apart, and additional clamps can be added if you wish to make an even longer brake. With 800 pounds of lifting strength per clamp, 1,600 pounds of down force is provided. That, combined with a 48" x 5.5" rubberwrapped contact point, provides a very effective brake for almost any size wagon.

Used in combination with straight cast ers at the opposite end of the wagon, a single large brake is all that is needed for a unit. If the movement of the wagon requires

it to have all swivel casters, then two brakes will need to be placed opposite of each other to truly lock down the movement of the wagon.

After the show comes down, the brakes can be detached and added to your brake inventory. You can create several sizes of brakes, then pull them off the shelf when ever you need them. If a brake needs to be modified for a specific unit, the most expensive part – the clamps – can be pulled from an earlier brake and repurposed at a very low cost.

Step 5: Wrap the brake in rubber drawer lining to improve its traction.

Step 6: Attach the brake to the wagon, ensuring that the handle lifts the unit slightly.

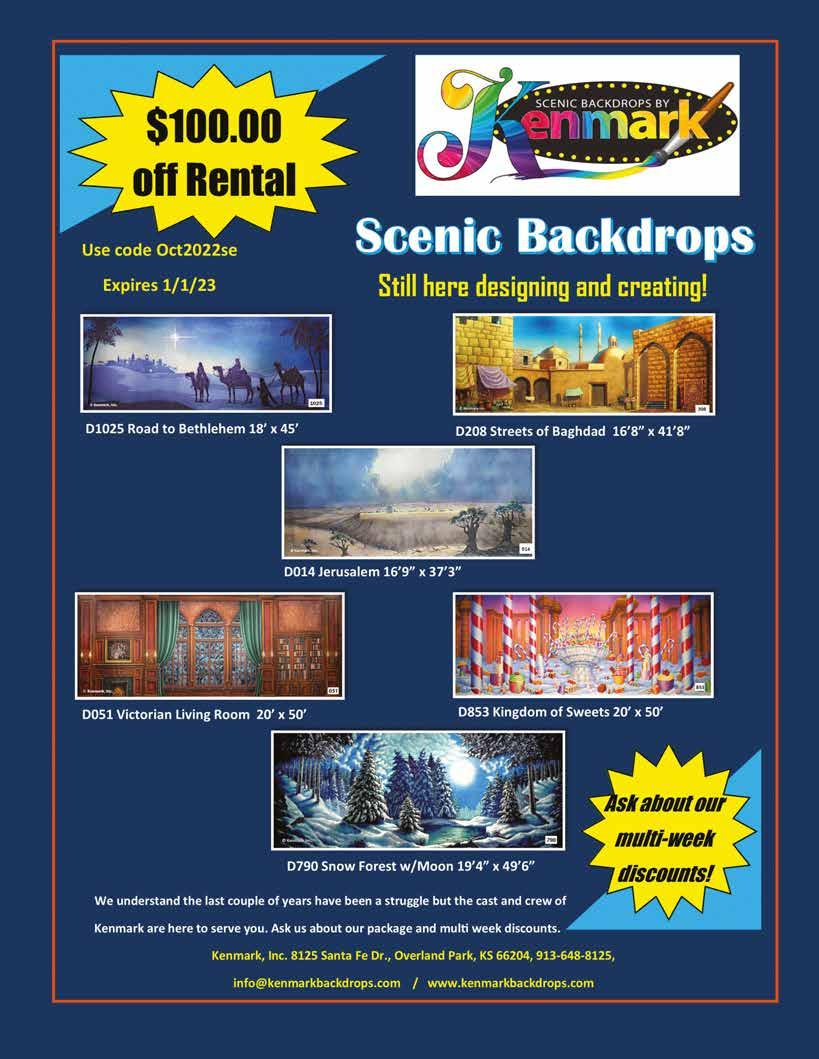

DeStaCo clamps (Model 610, 2@$41/each) $82.00

2x6x8' Spruce board 10.00

¼" wire rope clips (2@$2.25/each) 4.50

1.5"x1.5" angle steel (48" long) 20.00

Rubber drawer liner (whole roll) 20.00

Total Cost: $136.50

Send a brief summary of your idea to Outside the Box Editor David Glenn at djglenn@samford.edu.

Do you have a design/tech solution that would make a great Outside the Box column?Step 3: Cut steel handle and drill out appropriate holes for small U bolts. Step 4: Attach the steel piece to the handles to pair the clamps. David Glenn is the technical director/scenic designer at Samford University in Birmingham, AL. He is editor of the Outside the Box column and a member of the Southern Theatre Editorial Board.

A“A period play, a costume drama, a fantasy of entitlement, altruism and superiority.” That’s how author Edgar Villanueva describes philanthropy in his book Decolonizing Wealth: Indigenous Wisdom to Heal Divides and Restore Balance

For theatre professionals, the “period play” of traditional fundraising is easy to imagine. It’s an exclusive dinner with the guest director, guaranteed VIP seating or a table at the annual gala – and it typically features a cast of wealthy white folks who are accustomed to the benefits provided by the roles in which they’ve been cast as a result of their social location.

And many theatres continue to put on this same philanthropy song and dance, even as traditional fundraising methods such as donor levels, benefit systems and naming opportunities produce the same, if not declining, results.

According to a 2019 report from SMU DataArts, performing arts organizations consistently have the lowest return on fundraising when compared to other sectors, with the amount of money invested in earning fundraising dollars generally closer to the total funds raised than is the case in other sectors. And while many nonprofits saw an increase in giving during the pandemic, research from the Arts Funders Forum shows that out of nine sectors, giving to the arts had the largest overall decrease in 2019-2020 compared to 2018-2019, with a giving decline of 7.5%.

The fundraising sector’s resistance to change is deeply rooted in systemic racism, according to Vu Le, author of the popular blog Nonprofit AF and founding member of the community-centric fundraising move ment, which emphasizes equity and social justice.

“By centering the comfort of donors, most of whom are white, we perpetuate white saviorism, poverty tourism and inequity,” Le says, “while allow ing our donors to avoid confronting difficult realiza tions like the fact that wealth is built on colonization, slavery and other forms of injustice.”

So, if the comfort of donors keeps arts fundraisers beholden to practices that perpetuate injustice and, additionally, these practices don’t produce revenue growth – isn’t it time for something new?

Southern Theatre asked six rising field leaders, who represent a swath of arts fundraising experiences and perspectives, to share their thoughts on the future of arts fundraising. From innovative strategies to the importance of equitable fundraising practice and more, their insights paint an inspiring picture of what arts fundraising can be if we examine who current fundraising practices were designed to serve

and how those systems can be reimagined to redefine what it means to be a philanthropist. Communicating the social impact of the arts beyond entertainment

While giving to the arts declined in 2019-2020, g iving to sectors such as public/society benefit and

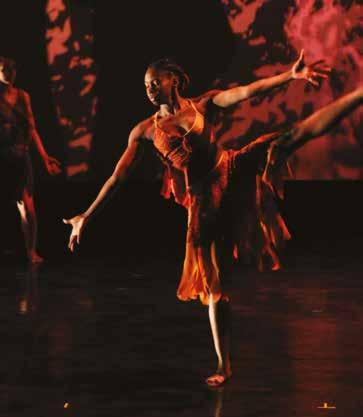

Alternate ROOTS is an Atlanta-based organization that supports the creation and presentation of original art rooted in community, place, tradition or spirit. (See related photo, opposite page.)

How did you make your way to arts fundraising? “My work in arts fundraising started while dancing professionally with Dayton Contemporary Dance Company. During annual galas, I was often paired with introverted dancers and seated at tables of current and potential donors. Once I realized I never had to ask people for money but rather tell my story and personal connection to the organization’s mission, the spark was lit.”

NOTE: After research on this story was completed, Suggs moved to a new position as director of development for Mid-America Arts Alliance, a nonprofit based in Kansas City, MO, that supports artists, cultural organizations and communities in the Mid-America region.

DEMARCUS AKEEM SUGGS

Director of Development

Alternate ROOTSO

DEMARCUS AKEEM SUGGS

Director of Development

Alternate ROOTSO

environment/animal benefit increased. And although most might attribute this decline to the lack of in-person arts programming, the Arts Funders Forum had a different conclusion: The arts just don’t do as good of a job communicating their societal benefit as other sectors do.

DeM arcus Akeem Suggs (he/him), interviewed for this story while serving as development director at Alternate ROOTS (ROOTS) until late June 2022, suggests that the best way to illustrate impact in a compelling way is via a message that underlines an organization’s mission and values. One of the keys, he said, is to high light the work of artists and communicate the deep value they bring to society as culture bearers.

“At ROOTS, we’ve focused on indi vidual and community transformation as a result of access and engagement in the arts,” Suggs said. “Artists move us – emotionally and intellectually. As James Baldwin so brilliantly noted,

artists also shape and reflect culture.”

An other strategy is to communicate theatre’s contribution to culture and the art form’s unique ability to be a conduit for empathy in a way that supports wellness, said Olivia Custodio (she/her), associate director of membership and annual fund at Oregon Shakespeare Festival (OSF).

“If you can take what you see on that stage, ruminate on it and perhaps imple ment what you learned, you’re going to live on a heightened plane of awareness for your neighbors,” Custodio said.

Th is heightened plane of awareness reaches beyond the theatre space and offers a tool for community members to better understand the world around them through arts experiences.

At S t. Louis Black Repertory Com pany (The Black Rep), Christina Yancy (she/her), who serves as acting fellow and development associate, notes that theatre can demonstrate the arts’ social impact by moving beyond just presenting theatre to

also using theatre as a platform to support what the company believes in.

For example, during the Black Lives Matter protests that followed the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor by police, “many arts organizations shared information about the movement, marches and ways their communities could support the movement,” Yancy said.

By holding a mirror up to society and supporting their communities through relevant programming as well as social justice work, theatres can operationalize their values, she said.

It ’s safe to say that many development professionals are staring down the face of grant reports that find them quantify ing their value through the number of programs they’ve held and the number of people they’ve reached over the past year, and those numbers are likely low in comparison to pre-pandemic data – for myriad reasons. And while there is certain ly value in tracking the number of people

who have engaged with the organization, considering how your programming has made an impact beyond those numbers is an invaluable exercise when communicat ing with funders, especially individual donors.

Ashlee Collins (she/her), development director at Lexington Children’s Theatre

(LCT) in Kentucky, recommends asking individual donors what brought them joy over the past two years.

“T hey almost always mention forms of entertainment and art,” she said.

These comments can serve as a jump ing-off point for conversations about the benefits of arts experiences for young

Oregon Shakespeare Festival is a Tony Award-winning theatre inspired by Shakespeare’s work and the cultural richness of the United States. It is among the oldest and larg est professional nonprofit theatres in the nation.

How did you make your way to arts fundraising? “As with most of us in this profession, it sort of fell into my lap! I began as an actor at an Equity theatre in Salt Lake City, then got a job in their box office. The artistic director noticed how much the patrons enjoyed interacting with me, and when a development spot opened up, she asked if I was interested. She hired a development consultant to show me the ropes and help me refine my skills as a grant writer, donor event planner and front-line fundraiser.”

OLIVIA CUSTODIO Associate Director of Membership and Annual Fund Oregon Shakespeare Festival OSF Artistic Director Nataki Garrett (left) talks with donors at an event during OSF’s 2022 Change Makers donor weekend. The Change Makers program has re-envisioned benefits to bring donors closer to the vision and purpose of the organization.people and families, as well as a way to connect the donor’s positive arts experi ences to LCT’s mission, Collins said. From increased empathy to community building to shared family experiences and more –as donors, they are a partner in making a meaningful impact.

For arts fundraisers, the pandemic provided many challenges as well as many opportunities to implement new strategies.

“I w as throwing out ideas, making videos and sharing them without truly knowing it would result in donations,” said Mercedes M. Brown (she/her), manager of individual giving and events at Dallas Theater Center.

Br own soon realized that donors were likely to give more than once over the course of the season if the theatre engaged with supporters directly via various appeals that made donating easy. These included a variety of opportuni

ties for interaction, created together with the marketing team, such as artist video testimonials that were shared on social media, virtual interview experiences for donors with the production team on the atre making and cast reunion opportuni ties. Brown also suggests introducing QR codes and text-to-give options, making giving easy and available via multiple platforms.

Af ter these efforts began, Brown found that not only were donors who would typically make one donation a year more likely to make repeat donations, but that new donors were attracted as well.

A qu ick Google search of “Giving Trends 2022” shows that the types of acces sible and flexible opportunities Brown mentions are high on many lists, making them a pandemic giving trend that won’t be going away anytime soon.

Ma ny Customer Relationship Manage ment (CRM) systems have text-to-give and email capabilities, with some even offering

support for personalized video appeals that can be customized for each donor. Free tools are also available online, including QR code generators as well as resources like the Donor Participation Project, an international community of fundraisers engaged in knowledge sharing and lively dialogue around the evolution of the field.

The fundraising strategy during the pandemic at Pacific Northwest Ballet (PNB), located in Seattle, WA, has included stating plainly to donors the importance of supporting artists.

Th e role that donations would play in “keeping dancers, musicians, administrators, school faculty and other groups employed and medically insured during this time was important for us to communicate to donors,” said Jackson Cooper (he/him), PNB’s major gifts manager.

The pandemic found ROOTS harness ing the power of collective action and

coalition building. An organization that connects “artists who have a commitment to making work in, with, by, for and about their communities and those whose cultur al work strives for social justice,” ROOTS made transformative change during the pandemic through partnerships.

“First, we worked with our lntercul tural Leadership Institute partners at First Peoples Fund, National Association of Latino Arts and Cultures (NALAC), PA’I Foundation and SIPP Culture to raise over $5 million for artists in our networks who were at risk of being overlooked by

CHRISTINA YANCY

St. Louis Black Repertory Company is one of the largest nonprofit professional African American theatre companies in the nation, providing platforms for theatre, dance and other creative expressions from the African American perspective.

How did you make your way to arts fundraising? “After graduating from the University of Montevallo in 2019, I joined St. Louis Black Repertory Company (The Black Rep) as a professional acting fellow. Administrative work is a large part of the fellowship. During the company’s regular office hours, fellows are given tasks in various departments. I joined the Development Department as a part of my administrative duties. During this time, I worked closely under the development director learning the ropes.”

The Black Rep has moved beyond just presenting theatre to also using theatre as a platform to support what the company believes in. It presented Fannie Lou Hamer, Speak On It!, on Oct. 2, 2020, at the administrative office of The Black Rep as part of a voter registration event leading up to the 2020 Presidential election. The live production was streamed to a larger audience through social media and also toured to three St. Louis community events in the metro area that same weekend. This production was also a continuation of The Black Rep’s collaboration with The Nebraska Repertory Theatre. The ongoing collaboration is entitled #realchange.

traditional philanthropy in the height of the pandemic,” said Suggs.

Fu nded through a partnership with the Mellon Foundation, the lntercultural Leadership Institute was able to distribute Crisis Relief Grants ranging from $1,000 to $20,000 to artists and organizations and to provide financial and technologi cal resources to lessen the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on livelihoods and the larger arts sector.

At t he same time, ROOTS served as an anchor member of the Southern Power Fund, initiated during the pandemic to raise funds and provide grant money to grassroots organizations in the South to address immediate needs in the com munity.

“Working with visionary Southern organizers, artists and leaders, we raised over $16 million to disburse unrestricted funds to frontline organizations and for mations,” Suggs said.

One of those organizations that ben

efited from the Southern Power Fund was Wideman Davis Dance.

“We were on tour and had just arrived in Chicago for a short stay when the pandemic hit,” said cofounder Thaddeus Davis (he/ him). “With the no-travel ban, we needed to find a way to continue our work from Chicago. With support from the Southern Power Fund, we created a hybrid work space that allowed us to continue residency work and community engagement activi ties. The Southern Power Fund allowed us to rent a workspace, purchase and install cameras, microphones and lights, and continue our scheduled residency activi ties and community work via Zoom. We continued working with residencies at the University of Southern Mississippi, Clemson University, Allen University, Columbia Housing Authority, Historic Columbia and Alabama Dance Festival, and presented at several conferences.”

Th e collaborative work by ROOTS and its partner organizations beautifully

illustrates principles of community-centric fundraising.

The community-centric fundraising movement seeks to systemically advance the nonprofit fundraising sector by elimi nating many of its traditional practices, which have a variety of negative conse quences, such as preventing important conversations about race, inequity and privilege; proliferating the “white savior complex” and perpetuating the “othering” of people the arts serve; crowding out the voices of people served; maintaining com petition for survival; and further marginal izing already marginalized communities.

In contrast to the donor-centric fundraising model popularized in the early 2000s that prioritizes the needs of donors, community-centric fundraising supports the needs of communities over individual organizations’ missions and is grounded in equity and social justice.

For Custodio at OSF, this type of fundraising starts with an acknowledgment that without its community, OSF would not exist.

“I n OSF’s new chapter with Nataki Garrett at the helm, we are turning toward the social justice work in our community, supporting other nonprofits and theatres in the region, uplifting voices and people who have been silenced and fighting for

equity in our economic landscape here,” said Custodio.

Ga rrett has served as the artistic direc tor at OSF since 2019 and, together with a cohort of Oregon arts leaders, secured $8 million for the state’s performing arts organizations from the federal relief fund package that Oregon received. Within OSF itself, Garrett has demonstrated her commitment to community, equity and

Lexington Children’s Theatre is a Lexington, KY-based professional youth theatre that was founded in 1938 and is dedicated to creating imaginative and compelling theatre experiences for young people and families.

How did you make your way to arts fundraising? “I had a ‘try it all’ mentality when studying theatre at Morehead State University. When the arts administration program was starting, it felt like the avenue where my talents shined brightest. Then, as in all nonprofits, the road leads you to the question, ‘How do we get money to do that really great thing?’ ”

Lexington Children’s Theatre has worked to encourage small gifts as a way to promote equity and involve children in discussions about giving. After performances, Collins talks from the stage about how donations help the theatre and asks families to consider making a gift as they leave. Those who donate any amount can also receive a commemorative button (shown above) celebrating the show they just watched.

uplifting voices through a variety of initia tives, including a dedication to producing new work; directing and producing plays from luminary playwrights like Katori Hall, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, Dominique Morisseau and Aziza Barnes; and opening OSF as a community place of refuge during the catastrophic Almeda fire that destroyed numerous homes in the area.

Tr aditional fundraising models his torically limited nonprofit collaboration through what the blog Nonprofit AF calls the “Nonprofit Hunger Games.” This style of operation, perpetuated by systemically flawed fundraising dynamics and more, promotes competition, scarcity and gate keeping, with many nonprofits preferring to attain their singular piece of the funding pie rather than collaborate with others, for fear that partnerships might lead to a smaller slice.

In her work at The Black Rep, Yancy has found that creating a united front among organizations is essential for all

nonprofits to thrive – and this starts with a conversation. Instead of hoarding contacts and information, she recommends creating a community of abundance by sharing information and experiences with others in the field.

“Many times, I have conversations with others in the development field, and we brainstorm ideas with each other and share experiences,” she said. “It always amazes me how many things we do similarly but also how many ideas we can gain from each other.”

The aforementioned Donor Participa tion Project offers a great example of fundraisers coming together globally to share resources for the benefit of the field. Additionally, many cities have formal and informal nonprofit meet-ups.

Brown and Suggs both echo the orga nizational, community and field-wide benefits of open dialogue.

“ROOTS has a lot of great partners in the field who amplify our work when we’re

not in some of the rooms where decisions are made,” Suggs said. “We do the same!”

Th is shift from a scarcity mindset to an abundance mindset also allows for more transparency and community support when communicating needs.

“Partnering with other organizations and sharing funding and resources will foster help in the community,” Brown said.

Making fundraising practices more equitable

For Cooper, equitable fundraising practice starts with having a solid under standing of your personal social location and relationship to wealth. Social location encompasses a combination of factors, including a person’s gender, race, social class, age, ability, religion, sexual orienta tion and geographic location.

“You must be authentic with yourself,” Cooper said. “It is one thing to know your organization’s values, but ask yourself: Do you know your own values? Do you

lead with those in your every day? How do you address equity in your practice as a fundraiser?”

Th is work requires many fundraisers to reflect on their own biases.

“Do not assume participants in educa

tion or community engagement programs or whom you label as the ‘under-served’ cannot donate,” said Brown.

Th ere are countless resources for confronting bias, which is a particularly necessary step for white arts fundraisers.

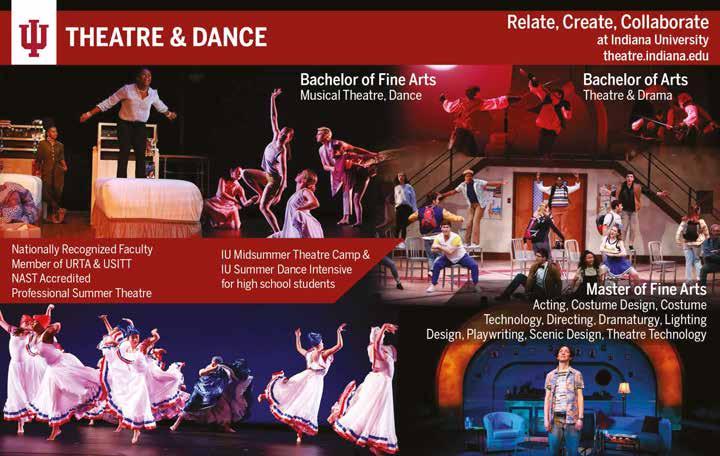

Dallas Theater Center, which was one of the first regional theatres in the country when it was founded in Texas in 1959, works to engage, entertain and inspire its diverse community by creating experiences that stimulate new ways of thinking and living.

How did you make your way to arts fundraising? ”I was fortunate to have exceptional arts programs in grade school. My parents deepened my interest with planned family outings to art museums and other cultural events during my childhood. I interned at an art gallery in college, which opened the door to various arts administrative roles, including arts fundraising. Originally, I went to graduate school to work with artists and museums but switched my focus to fundraising for nonprofit arts organizations.”

Above: When productions were canceled due to a COVID wave in the 2020-2021 season, Brown hosted a virtual happy hour for donors, titled Women of Color on Stage: Actresses Navigating the Theater Industry Roundtable.

Left: In its holiday message, Dallas Theater Center encouraged donors to give money via QR code to celebrate the return to live theatre.

Two exceptional books that explore these topics through a fundraising lens are Decolonizing Wealth: Indigenous Wisdom to Heal Divides and Restore Balance by Edgar Villanueva and The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Indus trial Complex by INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence.

Af ter beginning the essential and lifelong practice of self-work, it’s important to reflect on your understanding of the mission of your organization: Do your fundraising practices reflect the mission, vision and values of your company? Are you accepting donations from funders whose actions and intentions don’t align with your mission? Who do your fundraising practices actually serve?

Many organizations grappling with the historic impact of systemic racism have come to understand that develop ment work often upholds white saviorism and elitism through outdated benefits structures, such as guaranteeing donors the best seats, access to decision-making power in the organization and opportuni ties to meet artists, often with little agency being afforded to the actual artists in these scenarios.

“We have trained donors to receive ‘treats’ for their good behavior and gra ciousness and, in turn, the system is drenched in white supremacy, capital ism and transactional practices,” said Custodio.

He r major focus at OSF has been to reimagine their membership structure through a new Change Makers program. While benefit levels remain a part of the Change Makers program, the reenvisioned benefits are designed to bring donors closer to the vision and purpose of the organization through opportunities that highlight the impact of the work – not how great free drink tickets are.

Change Maker benefits include behindthe-scenes digital content, small group tours, first access to exciting news, oppor tunities to sit in on dress rehearsals and more.

“Our donors’ contributions have always been at the heart of making the change we want to inspire in the world,” Custodio said. “It [the new benefit structure] is a much better reflection of our collective values. Theatre belongs to everyone.”

Brown also said that older membership models reinforce the hierarchical systems in philanthropy and that benefits should be viewed as a symbol of gratitude rather than the sole reason someone gives to a nonprofit.

“T here is nothing wrong with offering donors tangibles and experiences,” she said. “However, promoting membership levels can create an ‘us’ vs. ‘them’ environ ment. This goes against ‘We See You White American Theatre’ and community-centric principles.”

At ROOTS, they are exploring ways to center members in fundraising efforts through artist-led giving circles. According to Philanthropy Together, giving circles are made up of people who pool their time and money together to make a positive change. This allows the artists involved in ROOTS to have a direct say in how the money raised by the organization is impacting other artists. The program is currently in the design phase with plans to pilot the program sometime in the fall.

“T he dream is that these circles will make autonomous decisions around fundraising and fund disbursement for our Solidarity Fund, an emergency assistance fund launched during the height of the pandemic,” Suggs said.

Equity in fundraising also means evalu ating the value placed on a donation and how donors are treated based on the size of their gift.

“Treating each donor with the same attention, stewardship and respect, no matter their giving level, is important for promoting equitable practices as fundrais ers,” Cooper said.

It ’s essential that gratitude is expressed for all gifts to the organization, be they money, time or resources, and that the gratitude is authentically communicated,

Pacific Northwest Ballet , founded in Seattle, WA, in 1972, is one of the largest ballet companies in the United States. The company of nearly 50 dancers presents more than 100 performances each year in Seattle and on tour.

How did you make your way to arts fundraising? ”I attended my first professional theatre performance when I was 14. It was a pay-what-you-can night for North Carolina Theatre in Raleigh, and there were nearly 1,200 community members packed into the theatre. It was the most fun I have ever had in a performance. When the night was over, I told my mom that that was what I wanted to do: bring a community of people in to experience the joy of live performances.”

For 50 years, Pacific Northwest Ballet has inspired audiences locally, nationally, and around the world. At home in Seattle, PNB presents over 250 performances, conversations, and community education events each year, reaching over 200,000 people each year.

PNB

has never been more committed to the artistry, innovation, and the joy we share when we gather for dance.

In its fundraising materials during the pandemic, Pacific Northwest Ballet has emphasized the important role donations play in keeping dancers, musicians and other artists employed, insured – and performing for their community.

which is directly connected to the fundraiser’s understanding of their self, their work and the work of their organization. According to Cooper, gratitude authenti cally expressed will promote long-term stewardship among supporters.

In addition, organizations should be mindful about how people are giving and on what platforms. Ask yourself: Is it easy for all people to give to your organization? How many clicks on your website does it take to make a gift? Are there options for smaller, recurring donations? Brown has found that these paths to giving are more welcoming for donors, regardless of socioeconomic background.

“Start incorporating digital payment apps and text-to-give, making it easier for anyone to give at any time,” she said.

At L CT, creating a culture where small giving is incentivized is also a way to promote equity and involve young people in a conversation around phi lanthropy. Following performances,

Collins will make her way onstage, talk about how donations support the theatre’s mission, and ask families to consider a gift on their way out. For a donation of any size, audience members can also receive a commemorative button celebrating the show.

“Some people donate a quarter, some a $20 bill,” Collins said. “On average, we have received $250 per run of a show.

Overall, that’s over $2,000 a year!”

In June 2020, a group of over 300 Black, I ndigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) theatre makers launched “We See You White American Theatre” (We See You WAT), which features a list of demands for historically white organizations, theatre makers, funders and more, based on the lived experiences of the BIPOC creators who came together to publish the list. The document encompasses not only change needed for artistic practice to

become anti-racist, but also for fundrais ing, grants and administration across the field.

As t he development associate at The Black Rep, a 45-year-old legacy Black arts organization, Yancy found that prior to the country’s recent and long overdue racial reckoning and the simultaneous global pandemic, BIPOC-led organiza tions were not being properly recognized or funded.

“However, as the pandemic occurred and theatres, specifically BIPOC-led theatres, began closing or taking hiatus, an influx of funders and donors realized how greatly impacted these organizations were and funding was specifically geared toward answering their call for assistance,” Yancy said. “Minority equity in funding and fundraising has become a priority rather than a passive occurrence.”

In her work, Collins has seen the same.

“I t hink that this global movement for justice has revealed gaping holes in access

Acting

The School of the Arts is the creative engine of Northern Kentucky University.

BA and BFA taught by a faculty of professional artists near the vibrant Cincinnati arts community, giving each student opportunities to stretch boundaries and discover new possibilities.

Theatre

TechnologyThe Lightning Thief: The Percy Jackson Musical The African Company Presents Richard III Annual Dance Concert

and resources,” Collins said. “And, in turn, granters and major funders are requiring more diversity in areas that count, which allows for organizations who meet that criteria a clearer path to the dollar.”

The data backs up their beliefs. Accord ing to SMU DataArts, in 2020, organiza tions that primarily serve Black, Indig enous, Latinx, Arab and Asian American communities received foundation, govern ment and corporate support that covered more expenses over time, and growth far exceeded inflation.

Suggs has seen this evolution in priori ties with his work at ROOTS but finds that more support on the regional and local levels is needed.

“I t hink a lot of leaders in national philanthropy heard the call for systemic change and were moved to act,” he said. “However, that work hasn’t been as readily adopted by state and local philanthropy. BIPOC organizations in our region still need national or regional validation to get

local buy-in and, even then, local funders have made obtaining support even more stringent.”

Wh ile support for organizations that serve diverse communities may be increas ing, a recent national survey by The Chronicle of Philanthropy of 1,168 charity leaders identified significant discrepancies in funding resources and opportunities when white-led organizations were com pared to BIPOC-led organizations. For example, 58% of BIPOC-led organizations received corporate donations in 2021, com pared to 71% of white-led groups, which in many ways highlights the challenges organizations like ROOTS are having with regard to local support.

There is no doubt that the future of arts f undraising is a complex and challenging one, but for these field leaders, there’s hope that the philanthropy period play of yore is evolving.

“I w ant to see arts fundraising anchored by grassroots communities and supplemented with funding from local, regional and national philanthropic partners,” Suggs said. “Alvin Ailey often said that ‘dance is for the people and should be given back to the people.’ Imagine if arts organizations saw themselves as belonging to the people and for the benefit of the people.”

Co oper also sees communicating the vitality of the arts as an important piece of the future.

“I hope that arts fundraisers reckon with the universal power of performance and gathering to create a powerful message to community members that the arts bring us closer together as people,” Cooper said.

Si milarly, Collins works to amplify the importance of arts education for communi ties.

“I hope that in my daily work and inter actions I am able to share and communicate just how fulfilling arts education can be

At Boston University School of Theatre, we are curious learners who seize opportunities to expand our journeys and enhance our artistry.

Through headlong risk taking, we bring concepts into existence and unleash ideas to build connections that shape the world.

Learn more at bu.edu/cfa/theatre!

@buarts

and inspire others to fight the good fight,” she said.

Fo r Yancy, a hopeful future for arts fundraising relies not only on communica tion, but also on creativity.

“My greatest hope, especially as we rise from the decline of this pandemic, is that we are able to remember and retain our creativity,” Yancy said. “It is because of creativity and innovation that many arts organizations were able to survive this period.”

Whe ther organizations commit to implementing innovative and equitable strategies or focus on grassroots organiz ing and cutting ties with donors whose values no longer align with the values of the organization, the future of arts fund raising is ready for a reckoning.

“My hope is that the collective ‘we’ of arts fundraising continue to focus on the art and artists and move away from bending over backwards for the donors who aren’t interested in evolving with

us as organizations,” said Custodio. “We cannot be afraid to release donors who don’t align with our current values and mission.”

Br own notes that she hears “talking points on solutions, but making an equi table change to arts fundraising is an uphill battle.”

She sees a need for more BIPOC arts fundraisers as well as greater use of grassroots strategies, both of which will require intentional and systemic change throughout the field.

“It’s time to reinvent philanthropy,” Brown said.

The great news is, a growing number of arts fundraisers are intent on doing just that. n

Bachelor

Fostering “cross-trained

(K-12).

Tiffany Dupont Novak (she/her) is the development manager at Actors Theatre of Louisville in Kentucky and a member of the Southern Theatre Editorial Board.

It’s the day they’ve waited for all semester: time to announce the theatrical season for next year. Students, educators and audience members all wait with bated breath.

The reveal is here! They go to their preferred social media page to check it out, and they are left … confused.

St udent 1: T here are no roles for me.

St udent 2: W hy are we always playing the same types of roles?

Patron 1: I’ve never heard of any of these shows.

Patron 2: I’ve already seen these shows.

Patron 3: Can’t they do shows that appeal to others besides college students?

Educator 1: How am I going to have students write good papers on such a commercially focused season?

Educator 2: How am I going to get students excited to go watch a bunch of shows they have never heard of?

ALL : W hat were they thinking?

What indeed is the thinking that goes on in the background of the season selection process? In the vast corpus of published and unpublished plays, new works and classics, dramas and comedies, musicals and Shakespeare, how does a college go about select ing a season that will be of interest and present good educational opportunities to students, performers and designers, while still appealing to a vast array of patrons, parents and young people?

It ’s a tricky needle to thread, so Southern Theatre reached out via an online survey to institutions in SETC’s database to learn how they make their selec tions. We received responses from 157 representatives of state universities, private colleges, community colleges and more from across the country, spanning from Wyoming to Massachusetts, from Oklahoma to Florida, from Alabama to Michigan.

One of the things that is abundantly clear from t he responses is that colleges and universities have a lot to weigh when building a season. And they have different constituencies to satisfy that often have different expectations.

“It’s often like a book that sort of writes itself,” said Scott Gagnon (he/him), the director of the Theatre Arts Program at Emmanuel College in Boston. “It’s a fascinating balancing act between where both the students and I find ourselves artistically, what audi ences want to see and what the students want to perform and design.”

Most surveyed schools shared the same primary focus: choosing shows that support that department’s pedagogy. At Berea College, a small liberal arts work college in Kentucky, Theatre & Film Department

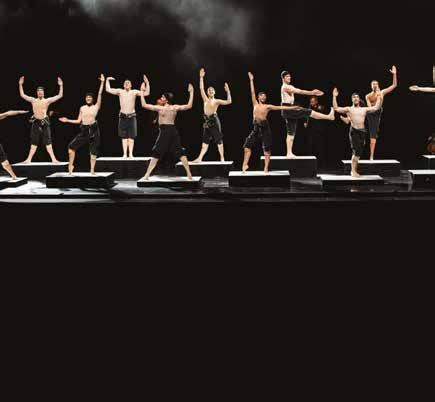

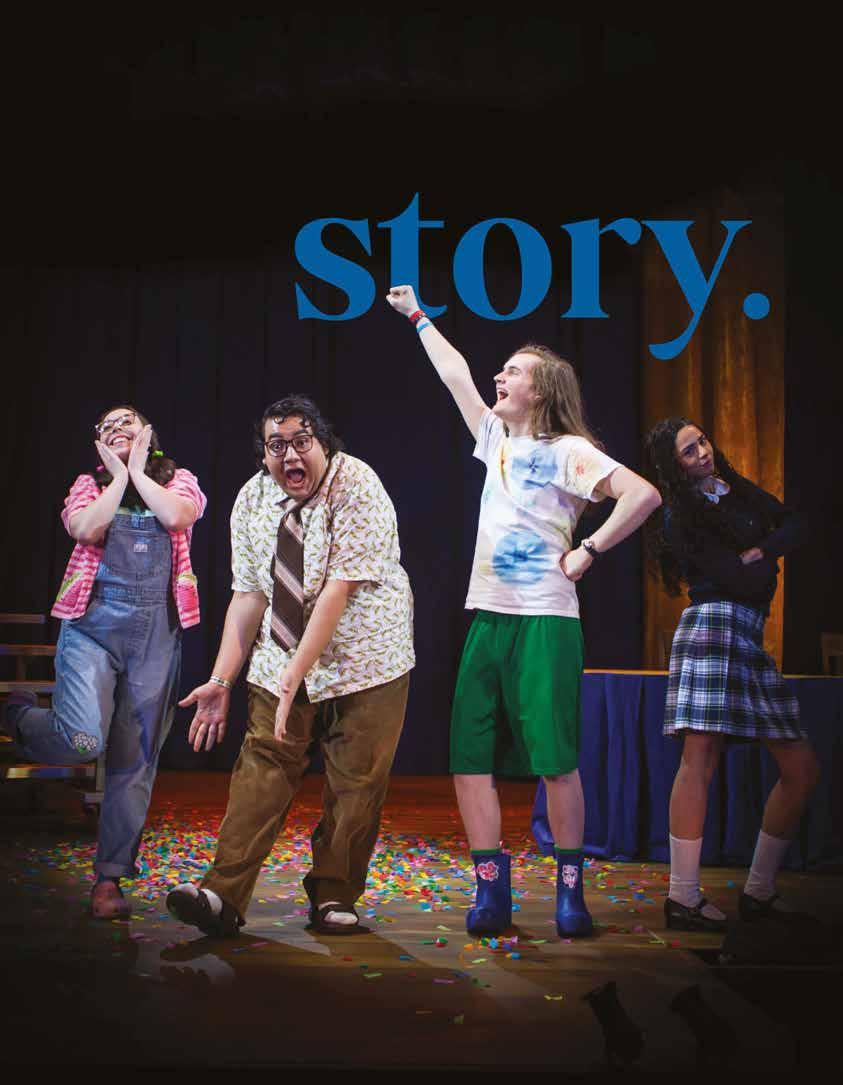

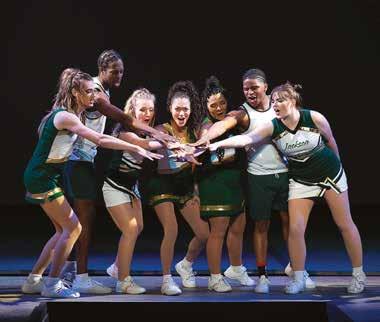

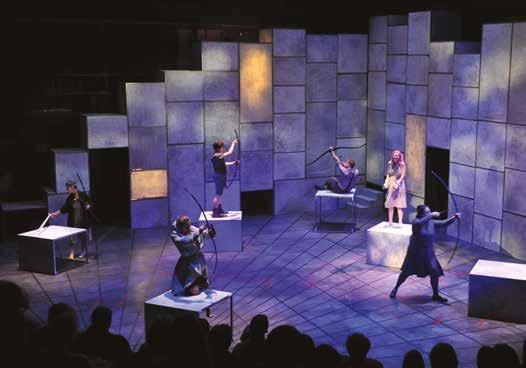

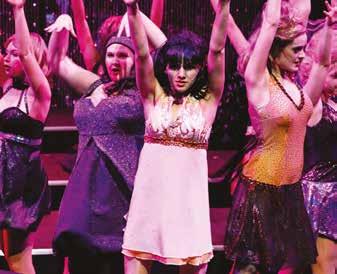

OPPOSITE PAGE: A number of school representatives said they work to reflect diversity in their season choices. For example, Ball State University says nine of the 10 shows in its 2021-2022 season were created, directed and/or choreographed by BIPOC, nonbinary, gender nonconforming, LGBTQ or female voices. The shows included (clockwise from top left): Everybody, by Branden JacobsJenkins; Skin and Bones, music and lyrics by Ben Clark, book by Andrew Kramer; Bring It On, music by Tom Kitt and Lin-Manuel Miranda, lyrics by Amanda Green and Lin-Manuel Miranda, libretto by Jeff Whitty; Significant Other, by Joshua Harmon; Roe, by Lisa Loomer; and Coppélia, choreographed by Lisa Carter and Melanie Swihart.

chair Adanma Onyedike Barton (she/her) said the top three considerations when faculty choose shows are the pedagogical relevance for the performers/designers, the opportunity to showcase student talent, and ensuring opportunities for students of color. They especially look for shows that provide opportunities for students to work in key roles.

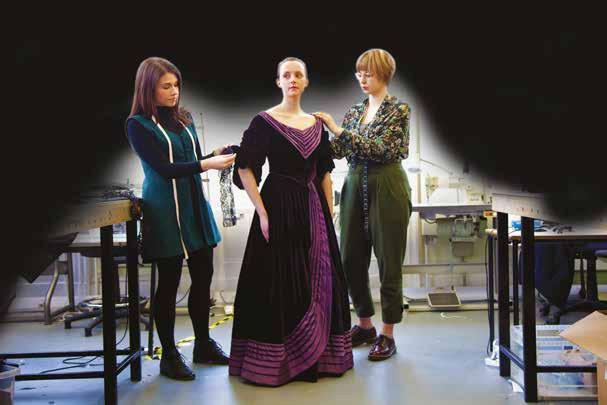

“We have a commitment to diversity, and students have jobs they are paid for (costume, hair, makeup, lights, sound, props) that help them move on profession ally after graduation,” Barton said.

As educational institutions, colleges and universities see the training and education of students as the primary focus. However, with different students studying different things, even that is not a straightforward area to satisfy.

Some shows have a heavy design foot print: lots of costumes, big sets, unique lighting requirements. In some cases, that’s a great challenge for design students. But sometimes it’s too much for a particular season’s budget or labor force to handle.

Some shows have a huge cast, which is exciting because that enables a school to give lots of performance students opportu nities to be on stage. However, those large casts often have very specific requirements.

And many schools struggle with fewer male-identifying students than female. Or, perhaps they have fewer students of color. If a show requires a role to be played by a performer of a specific race or ethnicity and they don’t have a student currently

Bart Williams Southeast Missouri State University Cape Girardeau, MO Joe Anderson University of Wisconsin-La Crosse La Crosse, WIwho is right for that role, that show is often disregarded.

Ba rt Williams (he/him), an asso ciate professor of acting, movement, stage combat and directing at Southeast Missouri State University, summarizes the primary departmental focus on students well: “We want material that will best equip our students (performers/designers) to get jobs when they graduate.”

And while student concerns make up the vast majority of a school’s focus when they are planning their seasons, they are also aware that selling tickets to family, friends, other students and season ticket holders is important or they won’t continue to patronize the theatre.

Jo e Anderson (he/him), chair of the Department of Theatre Arts at the Univer sity of Wisconsin-La Crosse, notes this is a lesson students need to learn as well.

“Clearly, we produce shows with the hope and expectation that audiences will attend,” Anderson said. “The reality is that our discipline can be very expensive and if we’re modeling for our students, we want to show them they can eventually earn a living in theatre. Revenue is an essential part of that success.”

At some institutions, ticket sales help determine the theatre department’s fund ing, making season choices vital for the bottom line.

“O ur production budgets are revenuebased on box office, so selling tickets is important to maintain our standards for future production,” said Lee Blair (he/

Accredited by National Association of Schools of Theatre

Accredited by National Association of Schools of Theatre

him), head of performance at West Virginia University.

So me other schools receive fund ing based on the number of students that attend their productions, so they must ensure student-friendly program ming. Some institutions even go so far as to provide complimentary tickets for their students, with the department’s budget influenced by how many students take advantage of that offer.

“All students at the university see our productions free of charge,” said Mark Harvey (he/him), head of the Theatre Department at the University of Minnesota Duluth. “How our season is embraced by students is critical since we are reimbursed for each ticket given away.”

Th ere are a tremendous number of factors that go into season selection because so many important elements are tied to the success of these productions. This makes people approach season selec tion in myriad ways.

In o ur survey, we found that while much of what schools look to do remains the same, their approaches to satisfy ing those contrasting demands are very different.

Almost every school that responded to t he survey does at least four shows a year. Many do more, although after that fourth production, many of the shows are studentproduced plays or shows in a smaller theatre space. Some schools are just focused on building a season for the fol

lowing year, but many schools have a long-term plan in mind.

“We have a grid, so we touch on various styles throughout a four-year period: for example, one Shakespeare, one rock musical, one Golden Age, etc.,” said Penny Maas (she/her), an associate professor of theatre at Texas Christian University.

Fo r those four shows, most schools endeavor to produce at least one musical. Musical theatre is still the most popular form of theatre in this country, and many schools have a healthy interest in musicals from their student body, other students on campus and independent patrons.

Over half the schools in our survey also produce one classical and one contempo rary show. This enables students to get experience on both ends of the theatrical spectrum and for audiences to see titles they may be familiar with, as well as newer ones that they could be encountering for the first time.

Wh ile there was no consensus on the most popular type of fourth show, the statistics tell us that after presenting their classical, contemporary and musical pro ductions, many schools put on a fourth show that can serve whatever areas they think their first three are not represent ing. The most common additional areas of focus we found after musicals, classical and contemporary plays were new works and theatre for young audiences.

Youth theatre is a wonderful training ground for young actors, many of whom break into the business working in that

Lee Blair West Virginia University Morgantown, WV Mark Harvey University of Minnesota Duluth Duluth, MN Penny Maas Texas Christian University Fort Worth, TX Kim Shire Carroll College Helena, MTOnstage and on camera, BFA and MFA students at the School of Drama at The New School craft their unique artistic identity as performers and collaborative makers in the heart of New York City.

Inspired by our faculty of working professionals and worldclass visiting artists, students develop their acting, writing, directing, and creative technology skills, finding new forms of authentic expression and originating work that is relevant, engaging, and powerful.

With a commitment to the art and the artist, we help students build their agency and independence, preparing them for a world that increasingly demands informed, agile, interdisciplinary makers. Notable Faculty

Sanjit De Silva

Stephen Karam

Christopher Shinn

Patrice Johnson Marjan Neshat Cara Hagan

Learn more about the School of Drama, part of The New School’s College of Performing Arts. newschool.edu/drama

Dan P. Hays Midland University Fremont, NE

Dan P. Hays Midland University Fremont, NE

Eve Graves Clark Atlanta University Atlanta, GA

Eve Graves Clark Atlanta University Atlanta, GA

arena. But frequently, other college stu dents are not as interested in paying for tickets for those shows. Additionally, edu cators who want to send their students to see shows and write college-level papers on the content struggle to meet student writing objectives with shows meant for children.

If s chools go the academically chal lenging route with titles that are perhaps less well-known or push the envelope, many patrons who don’t have theatri cal backgrounds aren’t interested in attending. And frequently, those patrons are the ones who stay in the area and sup port the department over the long term, not just over four-year stretches like many undergraduates and their families. So, they are an important part of the program’s outreach.

Wh ile you would hope a range of shows could satisfy diverse areas of focus, even then there are challenges to overcome based on budget, the makeup of the stu dent body, and pedagogical focuses from departments that differ in priorities.

“We have a rubric for making sure there are some family-friendly shows, some comedies, some dramas, a TYA piece, female leads predominant in most shows, at least eight characters, and one show that is certain to sell a lot of tickets, and one that probably won’t – it’s a very complex beast,” said Kim Shire (she/her), associate professor of theatre at Carroll College in Helena, MT.

Additionally, the key factors in decid

Will Lowry Lehigh University Bethlehem, PA David Haugen Ohio University Athens, OHing the season may change from year to year.

“We believe it is important when choos ing our seasons to take into account every factor,” said Dan P. Hays (he/him), direc tor of theatre at Midland University in Fremont, NE. “Some years, budget might be more of a concern than others, or we might want to emphasize a certain style of theatre that has not been featured for a while. But ultimately, the final question always is, ‘What is best for our students?’ That helps us finalize our show selection.”

While large universities generally produce four or more shows per season, some smaller schools produce fewer productions. For example, Clark Atlanta University produces two shows each year. Eve Graves (she/her), chair of the Department of Theatre and Com munication Studies, said the primary focus when designing the season is “ensuring pedagogically engaging material.”

An historically Black college or univer sity (HBCU), Clark Atlanta ranks providing opportunities for students of color as the top priority in choosing shows, with chal lenging students involved in the produc tion as a second priority.

Picking the material

Those who responded to the survey described a variety of approaches to the season selection process. While it can seem like the stakes are high because a lot is potentially riding on the selections, most universities say that it is not a contentious process. It can be challenging and long, but generally every department is aware

Editor: Scott PhillipsThe SMU Meadows Division of Theatre alumni do it all: perform on Broadway, star in TV shows and movies, start groundbreaking theatre companies, write award-winning plays, push the limits of directing and design, and continue to shape America’s artistic landscape. SMU Meadows Theatre is a nationally respected conservatory program within a strong liberal arts framework. Learn more at smu.edu/theatre.

of its goals, and all are working together to achieve them through their season selec tion process.

“I’ve led the season selection discussion for the last four years,” said Will Lowry (he/him), associate professor of theatre at Lehigh University. “It runs from roughly August to January–February, as it’s built around consensus. It’s a multi-phase process that allows for input throughout from faculty, staff and students, and each year has led towards a collaboratively established season garnering general enthusiasm.”

The biggest struggle departments have is making sure they are covering all of their bases. Theatre is a collaborative art form. That means multiple people from different disciplines work together to put on a show. Therefore, multiple people from those diverse disciplines must have input in how the season is selected.

for students. We are trying to find ways to simplify the process, so more students feel capable of joining.”

At E ast Tennessee State University (ETSU), one of the key considerations is whether a particular play will resonate at this point in time.

“We ask ‘why this play?, why now?’ because we want our selections to be relevant,” said Karen Brewster (she/her), chair of the Department of Theatre and Dance at ETSU. “We want to be responsive to societal situations, especially recently. We also listen closely to what our students say about the plays we are considering.”

Th ere are certainly positives to get ting more voices involved in the process. However, it can also make the process more complicated and longer. But for many schools, it’s a necessary complication to make sure that the pieces selected are

Over 50% of the school representatives said they select the offerings for their next season between October and December of the previous year.

“It’s all about the students’ needs, bal ancing that with budget, not over-loading tech, and getting the community to support the shows,” said Williams of Southeast Missouri State University. “We depend on our box office.”

Most schools have specific faculty mem bers selected to direct the shows in their season. Many also have a committee whose job is to select titles that they think would be good fits for the department. Most of the time, the directors of the shows in question are on the committee, and the group selects titles that are voted on by the rest of the department. Some schools include students on that committee, but most do not.

“O ur Season Selection Committee has been transitioning for the past seasons,” said David Haugen (he/him), head of per formance at the School of Theater at Ohio University. “Currently, it consists of an even number of faculty and students, with the school’s director being the final vote if one is needed. Being on the Season Selection Committee can be a burden, especially

supported by the entire department.

A pr ofessor at one state university shared details about its entire process, highlighting its complexity but also show ing how many voices have an opportunity to share input.

“O ur committee is made up of all areas within our department,” the professor said. “In order to maintain transparency amongst the student body, we send the notes from each weekly meeting to all stu dents and faculty within the department. Students are encouraged to contact their faculty representatives on the committee if they have ideas, thoughts or complaints.

“Dramaturgy grad students and direct ing grad students are also occasionally brought into the process to either present on the plays being considered or ‘pitch’ what they would like to work on in their thesis year.

“We begin our process with all areas submitting two to three plays or musicals to be considered. The committee utilizes a two-phase process, where each play

is first vetted on its pedagogical value within our department, and then phase two involves working down to a short list to consider the more practical side of production, including needed resources, scheduling, casting, special considerations such as fight choreography, intimacy direction, etc.”

Over 50% of the school representatives we surveyed said they select the offerings for their next season that begins in August more than eight months earlier – between October and December of the previous year. Over 75% of the schools had the season selected by March, five months before the season begins.

Some schools, like the University of West Georgia (UWG), start the process earlier.

“We are almost always in the season selection process,” said Amy Cuomo (she/ her), a professor of theatre at UWG. “Some times, we will select a play two years out.”

Ma ny professors note that they save the work they put in each year so it can be recycled in future years to make the process run more smoothly.

“We keep a spreadsheet of all the shows discussed from year to year that rose to the top of consideration,” said Anderson of the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. “That way, we can go back and look at shows that may not have been selected in a given year, but we were interested in producing for one reason or another. That way, we’re not starting from scratch each fall for the following year.”

Jonathon Taylor East Tennessee State University Johnson City, TN Eva Patton Ball State University Muncie, INWh ile many professional companies focus on a specific theme when building their seasons, that is not commonly the case in higher education. Broader themes or a focus on specific playwrights, eras or anything else take a back seat to more utilitarian concerns. Over 50% of those who responded to the survey said their primary goal when building a season was ensuring enough opportunities for their performers, designers and technicians. Responding to further questions about the top elements that go into their decisionmaking, over 50% chose pedagogical relevance for performers and designers as the No. 1 consideration.

In addition, the current conversations across society and the world of theatre about the importance of representation are having an impact as schools consider which plays and playwrights to produce. Many schools noted that they place a pre mium on highlighting diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), either through a show’s content or its creators.

“We try to balance decisions with DEI initiatives,” said Jonathon Taylor (he/ him), assistant professor of scenic design at ETSU. “So, in the past two seasons, we’ve done [the plays] Appropriate and Straight White Men, specifically because they deal with race, gender and equity issues.”

Eva Patton (she/her) of Ball State Uni versity’s Department of Theatre and Dance said her department “has committed to at least 60% of our theatre productions

being authored by BIPOC, nonbinary, gender nonconforming, LGBTQ and female voices. This has become a priority for us, and we are guided by it and making it happen!” Last season, nine of Ball State’s 10 productions were created, directed and/or choreographed by BIPOC, nonbinary, gender nonconforming, LGBTQ or female voices.

Si milarly, Eric van Baars (he/him), who retired in summer 2022 after 20 years as a faculty member and eight years as director of Kent State University’s School of Theatre and Dance, said that the school’s emphasis has included “presenting materi als from underrepresented playwrights … expanding the canon.”

He a lso noted the importance of pre senting plays that address current issues.

“W hile ensuring appropriate engage ment for performers and technicians is high focus, telling socially relevant stories is also a main focus,” van Baars said.

Julia Matthews (she/her), associate pro fessor of theatre at Albright College, also said season considerations there include “current events, themes in the public dis course,” as well as “connections to upcom ing exhibits.”

Lisa Brenner (she/her), a professor and theatre chair at Drew University, cited the following as major considerations: “diversity of material but also of format/ genre; scaffolding learning for our student directors and designers; dedication to new play development.”

Season selection has to satisfy varied

constituencies that want different things. And while the amount of information that is weighed can be daunting, it only underscores the profundity of this process in higher education.

Randall A. Enlow (he/him), an associate professor of design and technology at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, encapsulates the primary aim: “The goal is to train our students for grad school studies and/or beginning their careers. Play selection is first in support of linking curriculum and training with performance experience.”

In their search for a play for all seasons, schools weigh a nearly limitless amount of information. But their focus is always on presenting an array of ideas or themes in a way that serves the pedagogical needs of a program while also endeavoring to entertain audiences of varied backgrounds.

The University of Wisconsin-La Crosse’s Joe Anderson sums it up well, stating, “We try to choose a season that is diverse and fulfills the needs of our students and faculty. We also try to choose a season that audiences will find engaging, challenging, educational, enlightening and entertaining.”

n

Tom Alsip (he/him), an assistant professor and director of musical theatre at the University of New Hampshire, has participated in the season selection process at three universties. He is a member of the Southern Theatre Editorial Board.

Eric van Baars Retired from Kent State University Kent, OH

Julia Matthews Albright College Reading, PA

Lisa Brenner Drew University Madison, NJ

Randall A. Enlow University of North Carolina Wilmington Wilmington, NC

Eric van Baars Retired from Kent State University Kent, OH

Julia Matthews Albright College Reading, PA

Lisa Brenner Drew University Madison, NJ

Randall A. Enlow University of North Carolina Wilmington Wilmington, NC

Creativity comes to life at Belmont University, with top-ranked programs in the arts, music, film and design. Now, with the opening of the extraordinary Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, there's no better time for the creative community to engage with all Belmont has to offer.

Learn more at BELMONT.EDU/CREATIVECOMMUNITY.

Courtesy of Marin Theatre Company

Courtesy of Marin Theatre Company

FFor more than two years, theatre artists have been reeling from the ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the early days, Broadway houses shuttered, regional theatre productions were canceled, production licensing came to a halt, and actors, designers, technicians and musicians found themselves suddenly out of work. For playwrights, the pandemic presented challenging questions that many still struggle to answer, such as, “Will my work ever be produced again?” “Once the pandemic ends, will my pandemic play still be relevant?” and “When will theatre be normal again?”

Although all theatre workers were hit hard by the COVID pandemic, the financial loss to playwrights in particular has been substantial, notes Ralph Sevush (he/him), executive director of business affairs and general counsel of the Dramatists Guild.

“Dramatists were uniquely battered by the pandemic,” he said. “Unlike everyone else who works on a theatrical production, writers are not deemed ‘employees’ and, therefore, were not ‘out of work’; their plays were simply not being licensed. And, in some instances, theatres that had canceled productions were demanding that authors return their advances. There was also a spate of unlicensed digital presen tations of ‘archival recordings’ and … even digital licenses were of little financial value to authors. So, there was a devastating loss of income for our community.”

As the pandemic began in 2020, requests for production licensing quickly declined. During this difficult time, playwrights and the companies that license their works struggled to stay afloat. Although hard numbers are difficult to come by, many publishing representatives have anecdotal evidence regarding the decline in production licensing.

Li nda Habjan (she/her), vice president of acquisitions at Dramatic Publishing Company, said the drop in the number of requests for licensing at her company was major.

“We don’t have any statistics to share, but production requests pretty much came to a halt at the beginning of the pandemic,” she said.

Melody Fernandez (she/her), former director of licensing at Stage Rights, a Broadway Licensing Imprint, noted in an interview prior to her departure that many theatres tried to complete shows already in production as the pandemic began, but quickly moved on to cancellations.

“By the end of March 2020, they either had to cancel a closing weekend or a few performances or

postpone,” she said. “That was the first thing we saw. Because we were told that everything should reopen by July 2020, many theatres just moved their productions to summer or early fall. Then the shutdown continued. We saw a combination of canceled productions or postponing to 2021–2023.”