13 minute read

II Francis J. Straub

II

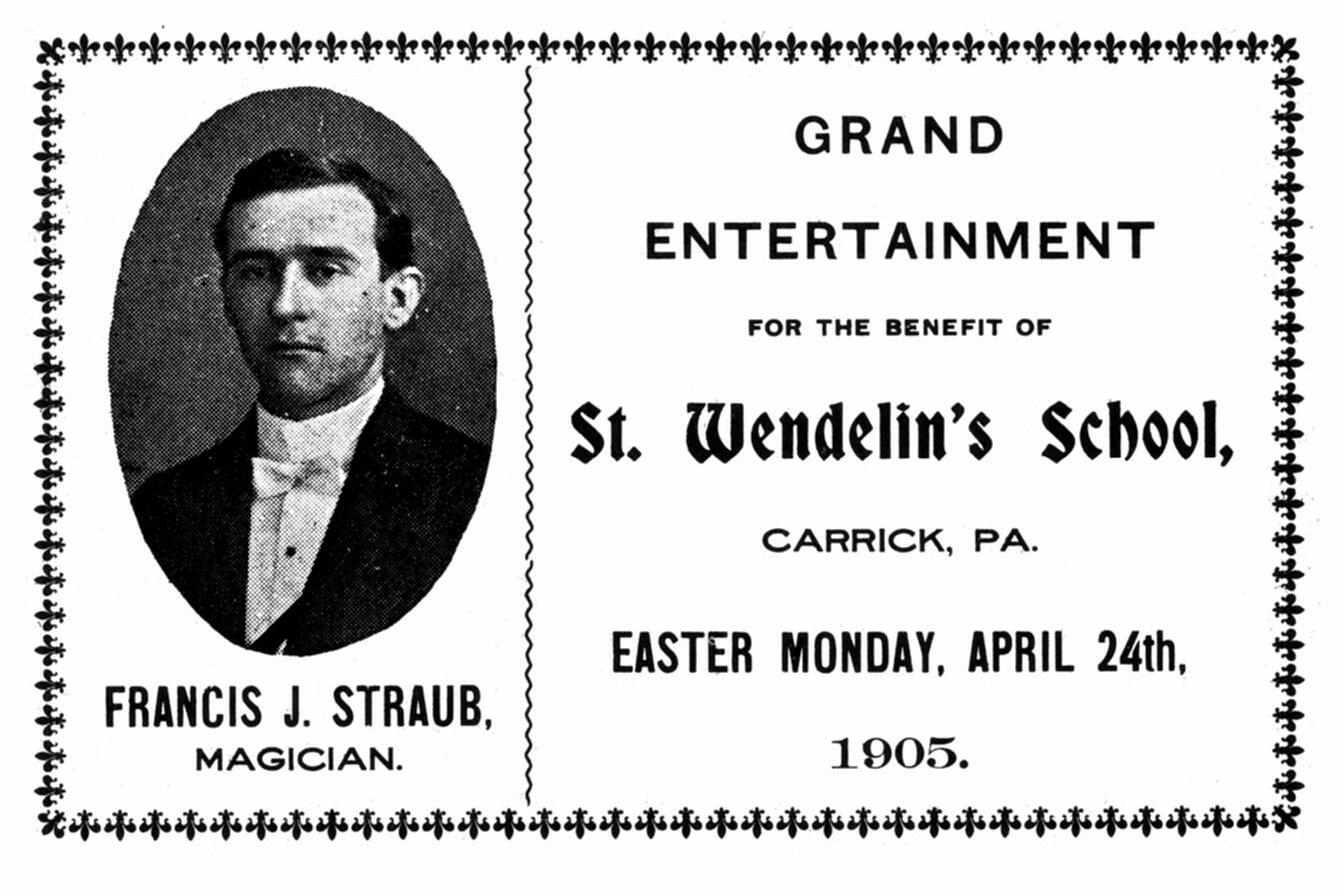

Francis J. Straub

Advertisement

The first known tests on cinder aggregate for concrete block were conducted by Prof. Ira H. Woolson at Columbia University in 1909, the same year cinderblock were approved for use in the borough of the Bronx. (Three years later, they were approved for all the New York boroughs.)

Other pioneers experimenting with lightweight aggregates during this period included Englishman W. J. Steward (issued a British patent in 1917 for an aggregate made from burned clay), C. E. Barglelaugh an American patent the same year for a ground lava rock aggregate), and Stephen Hayde who — in 1918 — was granted a patent "covering the preparation of materials suitable for use in the manufacture of molded articles." Hayde's materials were clay and shale that turned into bloated clay balls when burned at high temperatures. The resultant clinkers — which became widely known as Haydite — when crushed, were very light and first came into use as a concrete aggregate for ships during World War 1. The war ended before many ships were built, but the aggregate had been launched for a long and useful career.

Although all of these people and events were decidedly important in the evolution of the concrete masonry industry, they were dwarfed by the work — and the personality of an eccentric and individualistic Pennsylvania bricklayer named Francis J. Straub, the inventor of cinderblock. When Straub came along, the concrete masonry industry was lacking — more than anything else — imagination. Straub supplied it in copious quantities.

It has been claimed that several other plants produced cinderblock between 1910 and 1912, but little progress was made in the use of cinders in the manufacture of concrete block until F. J. Straub of New Kensington. Pa. began production in 1913. Francis Straub was a very good bricklayer who studied and experimented for many years with steam boiler cinders as an aggregate for concrete block. His purpose was to make block cheaper by using this waste material and at the same time produce a block that was lighter and nailable. Straub, himself, described this cinder concrete building block as "made from the entire ash or cinders from the combustion of either hard or soft coal, the large particles crushed to a point that will permit passage through a one-half-inch mesh screen. The intention in the manufacture of cinder concrete block is to produce a block of ample strength for all building requirements for either a bearing or non-bearing wall, and of sufficient porosity to provide the other essential characteristics of this cinder concrete block, namely, nailability, heat insulation, light weight. It is found that this is most readily accomplished by a mixture of about one part of cement to six parts of cinders. The strength of the block is specified at 800 lbs at 28 days age. The density and the

strength of the block can be greatly increased either by increasing the amount of cement or by changing the proportions of coarse and fine material in the aggregate."

Engineers and architects were perhaps understandably slow — in light of the chaotic condition of the concrete block industry at that time — to accept the new Straub product as a satisfactory building material. In many cases, it met with open ridicule — a fact the inventor liked to recall with glee in later years — but Straub persisted and built a number of houses and commercial buildings in his home area with his new product. He first applied for a U.S. patent covering his process on Nov. 9, 1915. It was refused. Straub finally convinced the patent office that he had something new in proposing that the complete residue of the fuel after burning the whole cinder should be used, and he was accordingly granted a patent on Jan. 16, 1917.

Straub's patent provided that "the ground mixture of cinders retains all of the usual accompanying adhering portions of the cinders in the resulting product, and it is essential that the original mass of cinder ashes as it comes from the furnace, grate bard, or other source remains in the resulting mixture without separation or change in proportion." It was further provided specifically that no sand or other aggregate should be added to the cinders. The greatest advantage of cinderblock, was, of course, its lighter weight. A standard 8 x 8 x 16" cinder block weighed 20 pounds less than a comparable sand and stone or gravel block. Much of the resistance of the masons and bricklayers to laying concrete block was thus eliminated by this lighter block.

Straub struggled during those early years to establish a few plants operating under his patent, the largest at Lancaster, Pa., where cinderblock was used for many buildings, ranging from garages and factories to school houses, banks, hospitals and churches, all with perfect success and much satisfaction to the owners.

Their use elsewhere, however, in the period 1915-1922 was relatively limited. By 1922, only about a dozen cinderblock plants had been licensed, all in the East and mostly in Pennsylvania. Only 25,000 cinderblock were made in 1919 (by 1926 there were 70 million being made!), but the promise was there and it had been spotted by some of Straub's competitors. One of them — needing to hype his business — began manufacturing a concrete building, product made from cinders and cement, with the addition of a fixed percentage of sand. Since the Straub patent specifically provided that no sand be used, the competitor apparently thought he was protecting himself legally. Straub started infringement proceedings and lost in a lower court. He appealed to the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and a unanimous decision was handed down on July 3, 1919, reversing the lower court and fully establishing the validity of St raub's patent. In the opinion of the appellate court, the fact that a nail could be driven into the block fixed the guilt definitely on the infringers. The court was primarily concerned with the qualities of the finished product, a precedent that would serve Straub well in the years ahead.

From this time on, Straub's procedure with poachers on his cinder block domain was routine. He would arrive in town, hire a taxi, visit the poacher's plant, buy a half-dozen concrete block, take them to a local court where he would triumphantly drive a nail into them and then file a complaint against the errant block producer. Thus the Court of Appeals decision greatly strengthened Straub's competitive position.

So did a merger with the Brooklyn Crozite Brick Corporation in April, 1922. Brooklyn Crozite Brick was a manufacturer of concrete brick with a large plant located in the geographical center of the borough of Brooklyn. While this product had been widely distributed, it was not a commercial success. E. B. Cadwell and Company had made a substantial investment in Crozite and had taken over its management to try and rehabilitate the business.

Cadwell was impressed with Straub and organized a new corporation known as Crozier-Straub. Inc., to which were transferred the patents owned by Crozier on machinery and processes for manufacturing concrete products and the cinderblock patent of Straub. The marriage was an immediate success. Less than a year later, Crozier-Straub, Inc. had 50 licenses — many of them in the midwest and beyond — with a production capacity of 40 million cinderblock per year.

The Straub licensees formed the National Cinder Concrete Products Association, with F. J. Straub himself, as president, for the stated purpose of cooperative research and promotion. It was also undoubtedly formed for mutual protection. While he was not entirely successful, Straub tried very hard to maintain the quality of his licensees' products. He fully realized that one plant producing an inferior cinderblock would bring discredit upon the entire group. Accordingly, he tried to insure a minimum compressive strength of 750 pounds per square inch of gross area, for all cinder block.

When Straub's product was first introduced — and before sufficient information was available regarding its characteristics — there was considerable hesitation on the part of engineers and building inspectors in permitting its use. But by 1923, after ten years of experience with the product, cinderblock was being adopted in many city building codes. A vital factor in this acceptance was a long series of tests in the early 1920s.

For two years, Straub cinderblock were pounded, pummeled, burned, hosed and subjected to every known building test — and passed them all. The Underwriters Laboratory (1922), the Structural Materials Laboratory of the Lewis Institute (1923), Rutgers University (1923), the Pittsburgh Test Laboratories and Columbia University (1924) all ran extensive strength tests on cinderblock after subjecting it to all sorts of punishment. All of these tests indicated that the strength of the cinderblock could be easily maintained at 700 psi at 30 days (the average recommended by the U.S. Dept. of Commerce for masonry walls at that time) and that the strength of the block increased perceptibly, at least up to six months.

Extensive fire tests indicated the cinderblock was absolutely firesafe. The Fire Underwriters Laboratory conducted numerous tests of its own and observed tests at Lancaster and Reading, Pa. Results indicated almost total fire resistance with very little loss in strength for the block walls. The Reading test was typical. A test house was built of sample panels of cinderblock, brick and hollow tile, subjected to a raging fire for more than an hour, then doused with water under pressure. Only two of the 637 cinderblock showed any damage, while almost all of the tile and brick were cracked and unfit for use.

Similar positive results emerged from frost and moisture tests. Although well within the absorption limits set by the U.S. Dept. of Commerce, cinderblock contained large internal air spaces. Because there was practically no capillary action, producing what is ordinarily known as suction in the clay products, there was also no tendency for moisture to be drawn through from a wet exterior cinderblock surface to the inside wall surface. Therefore, from the standpoint both of durability of the block against freezing when wet and the damp -proofness of the cinder block wall, the absorption recommendations commonly applied to other forms of concrete block did not necessarily apply to the cinderblock.

A typical series of freeze-thaw tests took place at Columbia University in 1924. In these tests, the saturated blocks were frozen, thawed, and resaturated twenty times. The strength of the blocks after repeated freezing and thawing cycles was in some cases, greater, in other cases, less, than the strength of similar blocks before freezing, from which researchers concluded that freezing and thawing had no particular effect upon the strength of these blocks.

Additional tests proved the high insulation qualities and soundproofness of cinderblock walls. The block could also be cut easily to a straight line and channeled for conduits and pipe. Nails could be driven into the block, and these nails would hold. And the rough surface texture of the cinderblock made a perfect base for the application of interior plaster and exterior stucco. Cinderblock was sold at about the same price as competing products, but the savings due to the ease of laying made cinderblock walls from 20 to 35 per cent less costly than brick.

Straub's particular genius transcended these impressive test results however. He not only subjected his block to extensive testing, but he merchandised the results — an element heretofore sadly missing in the concrete block industry.

For example, when a Straub licensee in Pennsylvania needed a new plant, it was built of Straub cinderblock, with one exterior face of the building used as a sample panel to demonstrate the application of stucco. The building also used a variety of Straub block, thus functioning as a salesroom as well as a manufacturing plant. When Straub put up a model home to demonstrate the possibilities of cinderblock he told a reporter, straightface, that the cost of the dwelling was so low that he was afraid to tell the truth

because he was certain that his word would be doubted. When a devastating fire raged through a commercial garage in Kingston, Pa. — destroying 100 cars — Straub got a letter from the fire chief attesting that "the only walls remaining intact were those built of Straub cinderblock, and I noticed particularly that none of the block or mortar joints bonding them were even fractured." He induced the Chief Engineer of the city of Pittsburgh to attend a fire test in Reading, then got him to write a letter to Straub saying, in part, "For more than four years I have been convinced that Straub blocks are paramount in fireproof qualities compared with any other known building material."

He solicited and — surprisingly, even in a far less complicated age — received endorsement letters from a wide variety of architects, engineers and builders. Typical is a solicited letter from Pittsburgh architect Carlton Strong, saying: "In reply to your inquiry for my opinion of the value of Straub Cinder Blocks in building construction, I beg to say, after considerable experience with them, that I have the highest opinion of their many structural properties."

All of this made highly digestible promotional fodder to Straub, who bundled it flamboyantly and fed it to the building trade in a distributional arc that grew steadily each year.

Personally, Straub was a delightful, unconventional man who marketed his eccentricities with the same skill he promoted his products. He was an outstanding amateur magician, appearing — when time permitted — on stages with professional entertainers. He also wrote voluminous letters — especially in his later years — pecked out laboriously on a typewriter, with a total disinterest in punctuation and exhibiting a freeform spelling that became identified over the years as Straubese. These letters have since become collectors items, as a few samples will illustrate.

For example, he wrote a trade magazine editor:

“You said in your letter the other day that you took the Liberty to call me F. J. But you forgot to say ACE HI O. H. F. J. Anyway, here is what F. J. wishes you to-do for the POOR Bricklayer.

Since you are going to have Plates made for the purpose of writing up some of the stuff that I was concerned with many years ago. And since it could be that I may live to be 50 or so, it could be that I would like to have the plates after you are through with them. As it could well be that some folks might want to read some of the trials and TRIBULATIONS (Say I did get thet big word in) that F. J. had to go through in getting people to think about read about and some few of them did buy some of the so called rediculis Cinder Blox.

For instance in Warren Ohio where straub patent cinder blox were Mfg. One time when I happened to be there a man came to our plant and F. J. showed him a service station that F. J. furnished the Blox for and layed up the job in red mortar. The man was so pleased that he said Mr. Straub if you will lay the Blox I will put up my new home out of your Blox. He was a pretty well known man in Warren so I said Man I don’t see how I will get the time to do but I will do it. The answer is a lot of folks saw his house and his wife was realy a big help for she sure was pleased to tell how they liked their house.”

To another correspondent, he explained carefully: “This Type Writer is Garenteed to make no missspelling. But it could be some of the Gears are out of kelter.”

And, describing one of his early competitors, he wrote: A mr Eberling of Cleveland Ohio a Bricklayer made a machine that ashe said every time the machine breathed out comes a truly formed Blox paterned after the Clay tile real low cost tile. His Blox were used in some real Sky Scrappers in Detroit. His product was lets say 5 times as strong as the clay tile. But too bad were about 3 times as heavy. And since in partisions no great strength was needed so my good friend Eberling fell by the wayside.

"Falling by the wayside" was a fate that eluded Francis J. Straub through a long and productiv e life. We will meet him again later in this story. But in the beginnings of the concrete masonry industry, he was a gust of fresh, shrewd. skillful and imaginative air that breathed some life and excitement into an industry that needed all of these things badly.